Is the Rage Behind Ice Cube's Rodney-King Rap Still Burning? (original) (raw)

A lot has changed in hip-hop and society since the L.A. riots and The Predator_. But not everything._

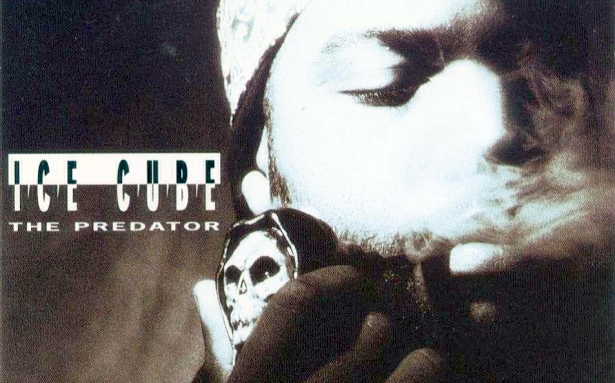

EMI

This past Sunday, Rodney King died at age 47, closing the book on a troubled life burdened by one of the more tragic cases of unwanted celebrity in recent American history. Only two days prior to King's death, the rapper and actor Ice Cube turned 43 years old, and 20 years ago no musical figure was more centrally and controversially tied to the riots that enfolded South Los Angeles in the wake of the King verdict. It was a connection that reached its culmination in November of 1992 with the release of The Predator, an album-length essay on insurrection whose historical specificity and raging force of purpose position leave it somewhere between a faded antique and a dusty but still-live grenade. In light of King's passing, it seems worth cleaning off.

Ice Cube had been at the forefront of the "gangsta rap" genre since his visionary turn on N.W.A.'s 1988 breakthrough Straight Outta Compton, an album that did for Los Angeles rap what Meet the Beatles did for British rock and roll. When South Los Angeles convulsed on April 29, 1992, the moral panic swarming around gangsta rap and its practitioners made it both the ideal scapegoat and imagined soundtrack for what conservative America perceived as urban race war. Banning Body Count's "Cop Killer" became a cause célèbre, even if it was a song far more people had heard of than had actually heard. Cube's own "Black Korea" from 1991's _Death Certificate_—an admittedly pretty deplorable piece of music, inspired by the shooting death of Natasha Harlins—was accused of inciting violence against Korean-Americans during the uprising.

The Predator was released in November of 1992 and would go on to sell two-million copies, a remarkable achievement given the narrowness of its subject matter. The album found Ice Cube consumed by the King affair, incessantly name-dropping the four unpunished officers (plus Daryl Gates and Willie Williams for good measure), explicitly menacing the 12 jurors who'd freed them, celebrating the chaos. "Riots ain't nothing but diets for the system," he declared, a precarious but stunning balance of theory and threat.

In a recent essay, Cord Jefferson went after Watch the Throne for Jay-Z and Kanye West's appropriations of Black Power iconography, rightly calling bullshit on the suggestion that a penchant for Hublot watches bears any honest resemblance to the anti-capitalist revolutionary ideologies of Fred Hampton or Angela Davis. The question of hip-hop's obligations to this intellectual tradition is hugely complicated and will probably never be satisfactorily answered, but 20 years ago its stakes seemed markedly different. Gangsta rap was a lot of things, all of which were outsized by definition: violent, swaggering, and breathlessly audacious, and far too often reprehensibly misogynistic, homophobic and racist. It was also, crucially, obsessed with police. No other genre of rap—and perhaps no genre of popular music, period—was marked by such explicit critiques of the state and state authority. And Ice Cube was its bleeding edge: The cover to Death Certificate featured Uncle Sam laid out on a mortuary slab.

MORE ON MUSIC

The Predator brought this to unprecedented levels, an album that lashed out not just at the state as a disciplinary apparatus but at the entire concept of America itself. To accuse the police of "fuckin' with me cause I'm a teenager / with a little bit of gold and a pager," as Cube had done on Straight Outta Compton, was to critique the practice of authority. To liken America to Nazi Germany and declare that "the Statue of Liberty ain't nothing but a lazy bitch," as he did on The Predator's title track, was to deny that authority's entire legitimacy. The Predator was a work of righteous indignation and ferocious self-defense, one that set out to be a revolutionary wholesale inversion of a bankrupt system and the moral apotheosis of gangsta rap, if such a thing was even possible.

Twenty years later it's still unclear that it was possible. The Predator was the last great album that Ice Cube ever made, but even as it reached the top of the charts, hip-hop was changing. A month after its release, Dr. Dre (Cube's former N.W.A. colleague) released The Chronic, a monstrous commercial success that refashioned gangsta rap as party music to extraordinarily influential ends. And the following two years would see the release of titles such as Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), Ready to Die, and Illmatic that forcefully reclaimed the creative vanguard of rap for New York.

It's also worth mentioning that the most famous and still-beloved track from The Predator is its most uncharacteristic. "It Was a Good Day" is an impossibly charming and strangely innocent celebration of quotidian pleasures, set to a classic sample of the Isley Brothers' "Footsteps in the Dark." The activities recounted in the song—breakfast, basketball, beer, sex—are so irresistibly catalogued they become universal in the simplest, most meaningful sense. When Rodney King asked "can't we all just get along" as the riots raged, his question was derided for its naivety, but there's something about peculiar beauty of "It Was a Good Day"—a song born to pour from car radios on summer afternoons from now until the end of time, putting the world in a better mood—that contains reconciliation, and the opening of another radicalism.

Rap has come a long way since 1992. The cultural mainstreaming of Ice Cube himself attests to this—as cultural critic Mark Anthony Neal recently pointed out on the occasion of Cube's birthday—and the arguments we're having over whether Jay-Z and Kanye's establishment coziness makes their appropriation of black power iconography hypocritical, or whether their blue-eyed, blonde-haired Academy Award-winning actress friend has access to the n-word, would have been flatly unintelligible 20 years ago. In some ways these are probably good things, and much of the Predator's relentless specificity has left it a product of its time, for better and worse. But the day that Rodney King died was the same day that thousands

gathered in New York in protest of stop-and-frisk tactics by the NYPD, all while websites and Twitter feeds buzzed about Drake and Chris Brown fighting over Battleship starlets and champagne bottles. Works of art like The Predator never age nearly as poorly as the wrong people want us to think they do.