The Best Books We Missed in 2016 (original) (raw)

“So many worthy books, so little space.”

I type those words all too often, as I wrote in this space last year, and the year before, when the list-making season arrived—and nothing has changed this year. So I’ll sigh once more over the predicament. Again and again, I have to deliver some version of that message to the many publicists who excitedly email me about the rich season of titles ahead. I tell reviewers, eager to share their views of this or that author’s latest effort, the same thing. Ditto authors themselves, a surprising number of whom come right out and ask: Can they expect any coverage in The Atlantic? The phrase, as I’ve admitted before, is sometimes a white lie, yet always the truth, too: We have room for only 30 or so book pieces a year in the Culture File. That means an awful lot of notable books go unnoticed by us.

In the holiday spirit, now is a moment to mention a sampling of 2016 books we wish we hadn’t missed—including two that my colleague Sophie Gilbert had hoped to write about. (So many worthy books, so little time!) And the brand new culture editor on our digital side, Jane Yong Kim, weighs in on poetry, a genre we’ve been especially remiss in attending to. We’ve asked their authors to pay it forward, and single out a few books themselves. What recent work has caught their expert eye? What book, however old, helped them write the one they’ve been busy promoting? —Ann Hulbert

Fiction

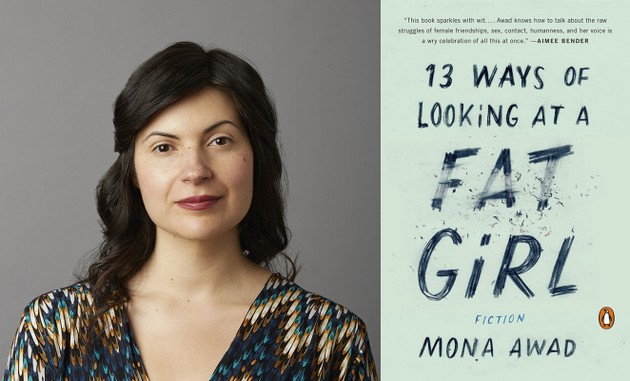

George Baier IV / Penguin / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic

One of the questions Mona Awad’s 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl prompts, through a series of vignettes about the same woman, is how rich life might be if all the energy women expended in service of skinniness could be redirected toward more life-affirming pursuits. In high school, Lizzie is already conscious of her size, becoming more acutely so with every personal relationship. Later, as Beth, she starves herself into submission. But it’s as Elizabeth, married, slender, and miserable, that the toxicity of her obsession becomes most apparent. Awad tells Lizzie’s story from a variety of different perspectives and in different scenes, some deeply funny, some dreamlike, many tragic. Throughout, her prose is lively, while her insight into the often-baffling complexities of being a woman is touching and sharp. —S.G.

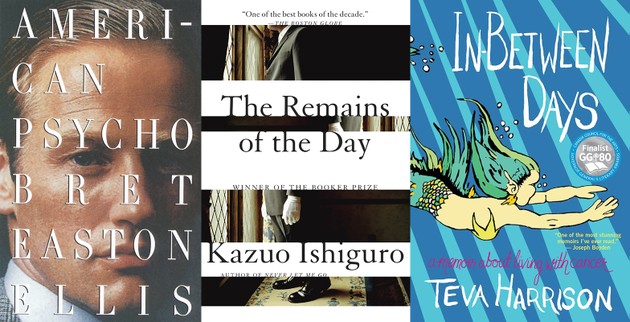

Vintage / House of Anansi

Mona Awad: Teva Harrison’s In-Between Days is an extraordinary graphic memoir about the author’s struggle with metastic breast cancer. Combining text and image, Harrison navigates the complex terrain of living with terminal illness in an intimate, honest, and remarkably brave voice that moved me deeply. The illustrations are particularly stunning, ranging from poignant titles like “Cancer Fraud” and “Trying on Small Talk” to truly heartbreaking ones such as “What I Want” and “Cancer Doesn’t Care.” There is great humor, vulnerability, fear, pain, life, love, and hope here. Like the greatest memoirs, Harrison goes right into the dark spaces and, in doing so, lets in the light.

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis really made an impression on me, though I can’t say that I was consciously aware of it as an influence when I was working on my book. I think it’s a brilliant, very disturbing, and complicated portrait of a monster, who is at the same time a product of his culture and his age. Certainly my main character, Lizzie, is no Patrick Bateman, but I do think I was interested in exploring a kind of monstrousness, a psychosis that our body-image-obsessed culture can bring out in us. Another favorite is The Remains of The Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. Not only is it a wonderful story with an incredibly rich and nuanced first-person voice, but I love the way Ishiguro can create a narrator who is so blind to certain truths inside himself, truths that are available to the reader to recognize, but that the narrator can’t access due to his own psychological and emotional blinkers.

Criticism

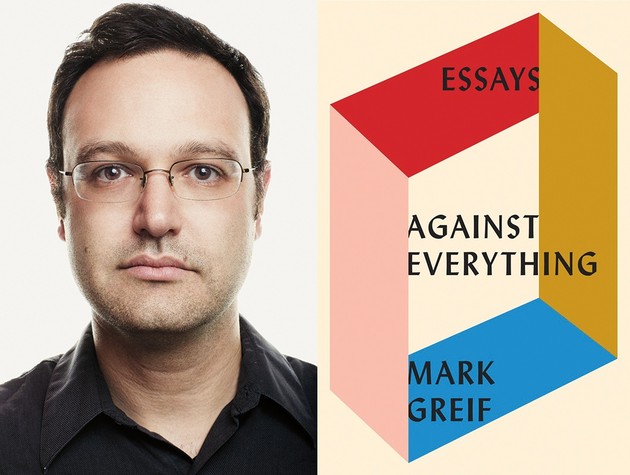

Roderick Aichinger / Pantheon

In a fall when so much political commentary has so quickly come to look dated and deluded, it is especially thrilling to read cultural commentary that spans more than a decade and is anything but. Mark Greif writes in his preface that as a child “I taught myself to overturn, undo, deflate, rearrange, unthink, and rethink.” That protean persistence of mind drives his essays, most of which first appeared in n+1, the journal he founded in 2004 with friends. His title may suggest obstreperousness, but Greif is above all fiercely curious. Whether he has the notorious Octomom in his sights, or our obsession with exercise, or confrontations with the police, he delivers insights about 21st-century America that will take you by surprise. As a guide to “what we call ‘experience’ today and what we name ‘reality,’” as he puts it, Greif will help you unthink and rethink, and who doesn’t need to do that? This gathering of his essays could not be better timed. —A.H.

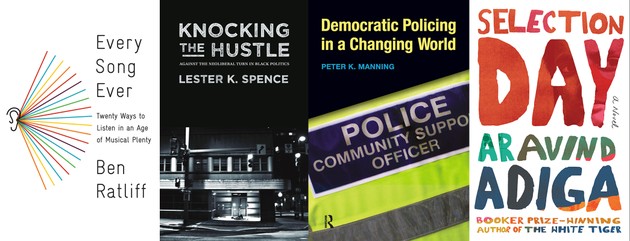

FSG / Punctum / Routledge / Scribner

Mark Greif: The best novel I read this year—Aravind Adiga’s _Selection Day_—was published in England and Europe, but won’t come out in the U.S. until January. In its primal triangle of rival brothers and a maniacal father, hell-bent on success in cricket in India, Adiga grips the passions while painting an extraordinary panorama of contemporary sports, greed, celebrity, and mundanity. As a literary master, Adiga has only advanced in his art since his Booker Prize-winning The White Tiger. Reaching back to books that could easily be missed because they came out just as 2015 was ending, I really admired Lester Spence’s sharp and mind-changing Knocking the Hustle: Against the Neoliberal Turn in Black Politics, a volume that’s both personally acute and analytically profound about black life and black insurgency in contemporary America. I’d recommend it to everyone. And a book that came out at the start of 2016, Ben Ratliff’s crystalline Every Song Ever, likewise dug under familiar categories of description—here, from aesthetics and music criticism—to open the reader’s eyes to truer visions of our artistic situation and experience.

As for older books that influenced me in writing Against Everything, there’s a long list of writers and thinkers to whom I wish I could pay tribute. But from within the literature of police sociology I read for my chapter on “Seeing Through Police,” let me just single out for praise the theorist and ethnographer Peter K. Manning, whose Democratic Policing in a Changing World (2010)—one exemplary title from his long career of superbly illuminating writings on police, security, and surveillance—would still be transformative reading for anyone who worries about police power and police integration into a fairer and better democratic social fabric.

Poetry

Peter Bienkowski / Copper Canyon Press

Ocean Vuong’s poems trace the sometimes messy contours of a life born of conflict and trauma, of a body animated by the love of mothers and strangers. Pulling from his family’s harrowing recollections of the Vietnam War, and from his own charged adolescent memories, he experiments confidently with different ways of expressing yearning. He places his subjects in bomb craters, on baseball fields, and even inside a ship-in-a-bottle, crafting live-wire imagery (“this is how we loved: a knife on the tongue turning into a tongue”) that gets at how weapons can be internalized, or foreign objects made familiar. Vuong, a 2016 Whiting Award winner, seems keenly aware of love as both a cost and an enduring extract of violence. His collection this year, with its impassioned pulse and shifting micro-geographies, offered me a radiant dose of just that insight. —J.Y.K.

HarperCollins / Wesleyan

Ocean Vuong: The book that remains on my desk, even after many re-readings, is Peter Gizzi’s Archeophonics, a National Book Award finalist this year and, arguably, his most ambitious and wildly thrilling achievement to date. The poems explore the world via sound: the way it disperses from an epicenter, touching hard surfaces only to return as an echo—changed, enriched, and bearing a history. “I’m just visiting this voice,” Gizzi begins, and throughout the collection it’s this notion of a transient self and of shifting speech that gives these poems their urgent currency. I have been carrying Archeophonics with me these past few months not as mere balm, but also as a trusty companion that might brush up against my own hard edges: “The old language is / the old language. It don’t mean shit. // It’s not where you begin / it’s how you finish.” For Gizzi, as long as language is used and rearranged, it can, despite its contradictions, pave a way forward and fashion an affirming architecture for the present. “I make sounds,” he writes, “[then] forget to die. I call it living.”

My family has a long history of learning disabilities, particularly dyslexia, and I myself came to reading quite late. But at 11, finally able to read at length on my own, I found the Scary Stories series by Alvin Schwartz. What immediately stunned me about the three volumes was how grotesque and surreal they were (despite their fourth-grade reading level). In one story, a boy, while digging in his backyard, finds a toe sticking out of the dirt. When he shows it to his mother she, without hesitation, tosses it into the pot of soup she’s making. The family goes on to eat the toe at dinner as though nothing is out of the ordinary. I learned later why I had such a strong connection to these stories. Schwartz had scoured books of folklore, collecting ghost stories and urban legends, some of them centuries old and originating from oral traditions. Because of its graphic nature, the series was, for years, at the top of the American Library Association’s list of most challenged books. But I grew up in a house rich with storytelling and Schwartz’s tales, in all their visceral, enigmatic brutality, echoed the ones my grandma used to tell of Vietnam. While I was writing Night Sky With Exit Wounds, these stories resurfaced as vital players from my formal reading education, serving as a testament to the imagination’s potential to transform violent and discordant histories into art.

Biography

Richard Blower / St. Martin’s Press

I kept wondering, reading Laura Thompson’s The Six, what the Mitford sisters might look like if they were coming of age in the 21st century rather than in the 1930s. Thompson’s meticulously researched, elegantly written book is a thorough history of one of England’s most eccentric families, gratifying to both Mitford enthusiasts and puzzled newbies. You might be familiar with Nancy, the eldest, and the author of Love in a Cold Climate and The Pursuit of Love, in both of which she sketched a hazily autobiographical account of her oddball childhood. But then there’s Diana (left her lovely husband for Oswald Mosley, head of the British Union of Fascists), Unity (friend of Hitler), Jessica (communist), Deborah (duchess), and Pamela (the quiet one). Thompson rifles through every skeleton in the Mitford closet while treating her subjects with great sympathy, even in their ugliest moments. It’s an artful history of a most enthralling family. —S.G.

Laura Thompson: Truthfulness is a peculiarly precious concept in these days of fake news, fake sincerity, and fake thought, which is why I particularly treasure the writing of Rachel Cusk. In both her novels and nonfiction she is fearless in saying what she means, rather than what readers might want to hear. She has been excoriated in some quarters for her books about motherhood (A Life’s Work) and separation (Aftermath), but the hysteria that she stirs up is of course a tribute to her honesty.

FSG

Her latest novel, Transit, is my book of 2016. It follows the brilliant Outline in being a series of encounters between the narrator—a writer, intermittently visible as she goes about her ordinary business—and assorted characters who in different ways offer her their story. That’s it. It is, as I see it, a literary quest to fathom the mystery of how to live. What is extraordinary is how this produces something so readable. Cusk is an admirer of D.H. Lawrence (as am I) and although, on the face of it, her extreme rigor with words couldn’t be more different from his vivid splurging prose, she has the same gift of making the numinous into something concrete.

I tend to prefer nonfiction that’s written by novelists. They know how to tell a story, what to emphasize and what to leave out. Nancy Mitford—also pretty fearless, beneath the aristocratic _politesse—_was a wonderful historical biographer, notably of Madame de Pompadour and Louis XIV, because she deployed all the same gifts that she used in her fiction: the entrancing authorial voice, the firm grasp of human motivation, the narrative flow into which research was so easily absorbed. So when writing my book about the Mitford sisters, I had Nancy in my head, not just as subject matter but as delightful inspiration. Rather as she, in turn, had been inspired by the words of her own biographical subject, Voltaire, who once wrote, “The secret of being a bore is to tell everything.”