'Carol Rama: Antibodies' at the New Museum Is Stunning: Review (original) (raw)

The Sad, Ecstatic Passions of Carol Rama

Over six prolific decades, the self-taught Italian artist explored the female body and its social context with curiosity and urgency.

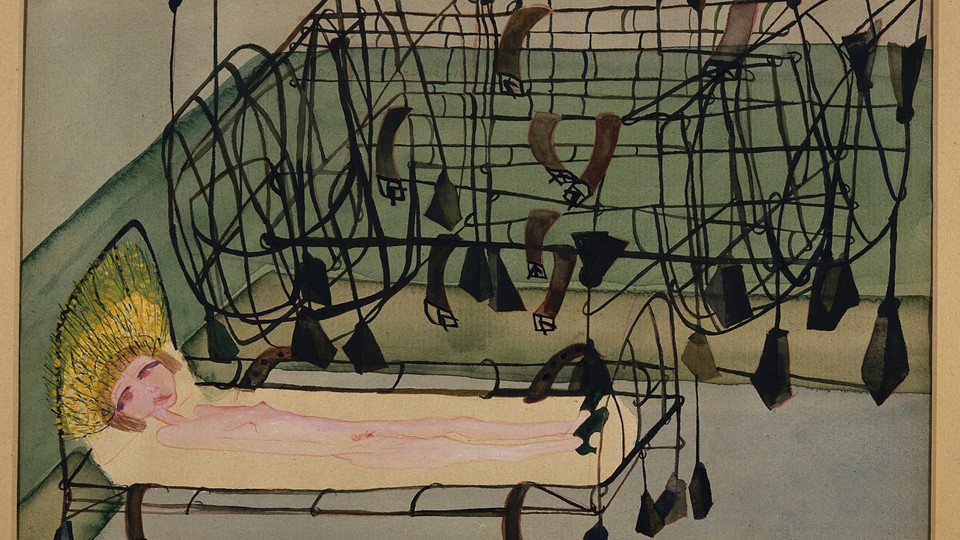

Carol Rama's 1940 painting Appassionata (Carol Rama / New Museum)

In 1945 in Turin, a solo exhibit of paintings by a young Italian artist was shut down. The works on display were propulsive with energy and psychologically driven: They depicted naked, often flower-crowned, women wagging their red tongues; defecating; copulating with snakes (or, perhaps deploying them as makeshift penises); and confined in psychiatric wards, wearing heels and nothing else. The delicate watercolors, tinged with pinks, greens, and crimsons, were interpretable as subtle stabs at Fascism and at societal responses to “deviant” female behavior. The police closed down the exhibit on opening day.

These paintings were the work of Carol Rama—and many of them no longer exist, either lost or destroyed. The incident of censorship is a footnote of art history but nonetheless marks an important moment for Rama’s career and, by extension, for artists like Cindy Sherman and Kiki Smith who would later be inspired by her. The shut-down would guide Rama’s aesthetic choices—she stopped making figurative pieces for years after, though hints of the human form remained in her abstractions—and would cement her reputation as an artist intensely interested in women as sexual beings, as medical curiosities, and as social symbols.

Recommended Reading

Rama—who died in 2015 at the age of 97—is getting some much-deserved recognition at the New Museum in New York City, with the most comprehensive exhibit of her work to date in the United States. (Other retrospectives have been staged recently in Venice and Barcelona.) Carol Rama: Antibodies represents an almost dizzying array of ideas, materials, and predilections across the artist’s six decades producing art: She used teeth, claws, burlap, and rubber; attached plastic eyeballs and syringes to canvases; and made paintings of disembodied breasts and testicles. She once crafted a bronze sculpture of a penis nestled inside a lady’s pump—in one fell swoop eliding the superficial distance between two trickily symbiotic symbols and poking some fun at Freud along the way. In all these works, Rama used womanhood as a lens for investigating anything from cultural norms and desire to illness and hysteria.

Of those themes, Rama’s interest in the interplay between health and society seems most enduring and deeply held. Italian asylums would be reformed in the ’60s and ’70s, but at the time that Rama was growing up, they were still clearinghouses for abuse, and for institutional perspectives that punished mental illness. Yet Rama, whose mother was committed to a psychiatric clinic when the artist was a child, saw it as a place of great vibrancy and liberty: Human bodies, to her eyes, assumed all manner of shapes and positions, seemingly with abandon. Or, as she would later say, “Madness is close to everybody.”

Nonna Carolina, 1936 (Carol Rama / New Museum)

The tension between freedom and constraint that the young Rama observed is evident elsewhere in the show, too: On a platform in the middle of one room are a couple of Rama’s “wedding dress” pieces: The garments—black sweater dresses with plush, red organs embroidered onto the chest—simultaneously flout marriage tradition and acknowledge the strange importance of costumes. In another work, a shiny row of human teeth gets repurposed as the spine of a beast perched on a man’s head: an animalistic portrait of the human psyche, joyfully unleashed yet inextricably linked to its corporeal host.

Those works, and many others, show Rama’s media-agnostic and voraciously curious approach to longstanding questions. If her watercolors of the ’40s provoke the most visceral and intimate response, Rama found a subtler sort of expression in the abstract pieces she pursued in the ’50s as she briefly joined up with the Concrete art movement and in the bricolage works of the ’60s that saw her create darkly emotive canvases affixed with animal claws and bits of fur—by turns abstruse and entirely tactile.

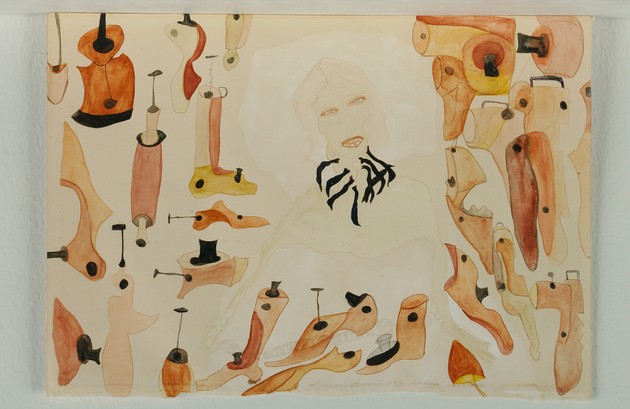

Spazio anche più che tempo, 1970 (Carol Rama / New Museum)

Rama’s rubber-based pieces—the gomme works of the ’70s—were in some ways even more subtle and count among her more intellectually interesting explorations. For these austere-looking but thematically complex works, Rama took inspiration from her father’s bike-tire factory, disassembling and flattening bicycle inner tubes to create mixed-media collages. While not figurative, many of these pieces bring to mind organs and veins. Occasionally, Rama molded the rubber, reminiscent of skin or casing, into anthropomorphic curves; at other times, she let the uncut circular tubes hang three-dimensionally from her canvases like protuberant bouquets.

La Mucca Pazza, 1998 (Carol Rama / New Museum)

The most stunning of the rubber works are those in her later mucca pazza series, Rama’s artistic response to the cultural fervor elicited by reports of mad cow disease. Intrigued by society’s need to turn the cows into both dangerous pariahs and mystical figures worthy of attention, she made a handful of simple compositions: She cut flesh-hued rubber into shapes reminiscent of udders, breasts, and testicles and placed them in a variety of positions on painted canvases. The symbolism is clear: The paintings, which she saw as “extraordinary self-portraits,” recall the longstanding social and literary archetype of the “mad” woman and embrace the fickle, politicized language of sickness. The series seemed particularly personal for Rama, who once referred to herself as a “premeditated lunatic” who painted “first and foremost to cure myself.”

Rama isn’t the only female artist of her generation to be awarded belated recognition in recent years. Her Italian compatriot Marisa Merz, who was part of the Arte Povera movement, as well as the Cuban geometric-abstractionist painter Carmen Herrera, have also received major retrospectives in the U.S. in the past two years, triggering familiar debates about delayed art-world celebrations of prodigious female talents. Similar conversations occurred in relation to the French sculptor Louise Bourgeois, who didn’t receive her first retrospective until she was in her 70s. For Rama, those early so-called “psychosexual” paintings and her difficult family circumstances—a mom who struggled with mental health, a father who killed himself—mean protofeminist and autobiographical frames have often been imposed on her work. (It seems no coincidence that broader appreciation initially came in 1980, with a reshowing of those original, censored watercolors.)

The artist herself appears to have had little patience for the industry’s late recognition; if few others acknowledged her decades of work, she herself did. Her studio in Turin, where she lived for most of her life, was meticulously arranged with collected objects and works, a suggestion that she cared about self-presentation and, perhaps, about preserving her own oeuvre. When she won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2003, Rama apparently posed the question,with some irritation: Why had it taken so long? She seemed to understand something that the Turin police of the ’40s did not: that, censored or not, her works would have a long and illuminating shelf-life.

About the Author

Jane Yong Kim is a deputy editor at The Atlantic, where she oversees the Culture, Family, and Books sections.