The Best Books We Missed in 2017 (original) (raw)

And the titles their authors say they loved

Katie Martin / Emily Jan / The Atlantic

Editor’s Note: Find all of _The Atlantic_’s “Best of 2017” coverage here.

“So many worthy books, so little space.”

I type those words all too often, and my colleagues on _The Atlantic_’s digital side, Jane Yong Kim and Sophie Gilbert, and I have now made a tradition of lamenting that predicament every year as the list-making season arrives. Working both online and in print, as we do, we really should revise the lament to include “—and not enough time.” To the many publicists who excitedly email me about the rich season of titles ahead, I’m always sighing about page constraints at the magazine. With only so many hours in a day to write and edit and so much to cover, the culture team online also looks longingly at books that deserve attention but don’t get it. We echo the message to reviewers who are eager to share their views of this or that author’s latest effort. If only we didn’t have to be so ruthless, we also say to authors themselves, a surprising number of whom come right out and ask: Can they expect any coverage in The Atlantic? The phrase, as I’ve admitted before, is sometimes a white lie, yet always the truth, too: Far too many notable books go unnoticed by us.

In the holiday spirit, now is a moment to mention a sampling of 2017 books we wish we hadn’t missed. We’ve asked their authors to pay it forward, and single out a few books themselves. What recent work has caught their expert eye? What book, however old, helped them write the one they’ve been busy promoting? —Ann Hulbert

Fiction

The Ninth Hour by Alice McDermott

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux

“His trouble was with time,” Alice McDermott writes at the start of her eighth novel, referring to a subway motorman—and husband and soon-to-have-been father—who commits suicide. That is not a spoiler: The young man’s death is what sets this time-haunted, mesmerizing book in motion. Set in early 20th-century Brooklyn, the novel follows his wife, Annie, and Sally, the daughter born some months later, as they make their way through days, years, and decades without him. The Little Nursing Sisters of the Sick Poor, who step in to help, do their best to impart the solace of “implacable routines” in a soiled world of endless suffering. McDermott wryly and wisely sees to it that they fail. Even for the nuns, and certainly for Annie and Sally—and for the descendants who figure as intriguing narrative voices—lives turn out to be shaped less by willed sacrifice than by the ebbs and flows of love. Time entraps and liberates, and in her inimitably evocative prose, McDermott spools out the past in bold and fascinating ways. — A.H.

The Unnamed Press / Atlantic Monthly Press / W.W. Norton & Company

Alice McDermott: Early in my career there was a notion—perhaps only a romantic myth—that first novels were meant to be investments in the future. Publishers, I was told, were on the lookout not only for blockbuster debuts, but also for work that offered the literary equivalent of Emily Dickinson’s thing with feathers: promise. I’m not sure anyone believes that anymore, but I still delight in reading fledgling novels that wink and shine with what’s to come. When the authors of these novels are former students, I’m more delighted still. Jessie Chaffee’s Florence in Ecstasy follows a young American woman, a recovering anorexic, as she tentatively reclaims her life—body and soul—during a stay in Florence, Italy. Chaffee’s prose is lovely, whether she’s describing the physical toll, and joy, of rowing on the Arno or the peculiar psychology of female saints who, in ecstasy, starved themselves for God. There’s an absorbing story here, a love story, a coming-of-age story, a gorgeous portrait of the city itself, its beauty and its decadence, but there’s also the thrilling glimpse of a brilliant young writer just setting out.

Lily Tuck’s brief seventh novel, Sisters, on the other hand, reminds a reader that experience, and expertise, has its privileges. Tuck writes with the steely-eyed assurance of an author who knows exactly what she’s doing—and an undercurrent of If you don’t trust me, to hell with you. The novel opens with a single sentence on an otherwise blank page: “We are not related—not remotely.” The unnamed narrator and the “she” of her obsession are, respectively, second and first wives of the same man. The story unfolds through a series of sharp, often oblique, vignettes of domestic life, told in a voice that is at once cool and furious. Jealousy as a corrosive passion is beautifully dissected here in Tuck’s signature style, which is always taut, precise, and, ultimately, unnerving.

As a woman who writes, I’ve done my fair share of complaining about the dead white males whose work formed, pretty much exclusively, the foundation of my literary education. With that situation duly noted, and, in the years since, amended, I’m now free to suggest that those guys were also pretty good. Joseph Conrad, for instance. As I considered the structure of The Ninth Hour, I reread Heart of Darkness just to observe, once again, how skillfully the narrative “we” that opens the book gives way to the sustained “I” of Marlow’s story. How willingly a reader is absorbed into the extended, vividly recollected, quoted, tale of Kurtz as told by Marlow, without ever once pausing to ask, “Wait a minute, how does he remember all this?” or “Who talks like this?” or, shades of overwrought writing workshops, “Is this supposed to be meta?” Never hurts to observe the effortless expertise of the greats, even as you hope to devise something new, and entirely your own.

History

The Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World by Lizzie Collingham

Basic Books

One of the most intriguing revelations in Lizzie Collingham’s newest book involves the humble Christmas pudding, that staple of festive British dinners. The dish—composed of dried fruit, sugar, spices, and brandy—unites ingredients derived from Britain’s colonies, symbolizing the nation’s global and commercial power. “To be a Victorian Englishman,” Collingham writes, “was to possess the power to eat the world.” The Taste of Empire is a fascinating history of exactly how food shaped and informed colonialism, and vice versa. From the East India Company’s pepper imports to the flourishing sugar trade in the Caribbean, food played a primary role in stoking the growth of the British Empire, often with horrific consequences. (At its peak in 1688, the British taste for sugar led to the enslavement of 20,000 Africans a year in the Caribbean.) Collingham explores these connections in compelling prose, making human stories central to her investigation. Her anecdotes about 17th-century Irish maids sweatily churning butter and Indian women grinding chilies in cooking spaces purified by cow dung bring the past to life in ways most historians can only dream of. — S.G.

Viking / 4th Estate / Oxford University Press

Lizzie Collingham: In 2017 my reading year began well when Tracy Chevalier’s novel At the Edge of the Orchard transported me to 19th-century Ohio and the frontiers of American settlement, a subject fascinating for a historian of empire. The quarrelsome Goodenough family are struggling to nurture an apple orchard in the Black Swamp and then, when their son Robert runs away, he takes us to post–Gold Rush California where he finds solace collecting seedlings in the serene gloom beneath the giant redwoods. Novelists create a different kind of conduit to the past than nonfiction writers but in Victorians Undone: Tales of the Flesh in the Age of Decorum, Kathryn Hughes is equally skilled in her ability to imaginatively place her reader inside the Victorian body. Having in her last book dismantled the cozy image of Mrs. Beeton as a matron ensconced in her kitchen, in her latest, Hughes gives us an unvarnished picture of Queen Victoria as a spiteful, greedy, and smelly young woman. She explains the aesthetic behind the extravagantly bushy Victorian beard—worth growing for its ability to hide bad teeth and eczema even if it did tend to catch stray scraps of food. And she sets to rights an oft-repeated claim that the 19th-century murder victim Fanny Adams was a Portsmouth prostitute. In fact, she was an 8-year-old dismembered by her murderer and her memory has been passed down to us via sailors’ grisly humor—they named their canned meat Fanny Adams as it was cut into small pieces.

In Feast: Why Humans Share Food Martin Jones reveals how a careful reading of the distinct pattern of archaeological remains allowed him to reconstruct a series of meals in different places and times. Concentrations of broken barley seed around limestone basins in the remains of a Syrian kitchen tell us that 11,000 years ago the people of the Euphrates valley ate tabbouleh salad, just as they do today. And from the latrine of a Roman house in Colchester we can see that while the inhabitants enjoyed imported figs and dates, they also suffered from whipworms. His book inspired me to structure The Taste of Empire around meals and in each chapter to emulate the archaeological unpacking of the meaning of meals by asking what the circumstances were that made each meal possible.

Philosophy

Why Buddhism Is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment by Robert Wright

Simon & Schuster

The title leaves little doubt that its author is a big thinker, as you might already know from a list of Robert Wright’s previous books—The Moral Animal, Nonzero, and The Evolution of God. What you wouldn’t guess until you dipped into his latest undertaking is that he is also, as he puts it, “a naturally bad meditator.” (He is a former colleague, and I wouldn’t have pegged him as a meditator at all.) He shares personal experiences on his cushion and at retreats, but he doesn’t promise regular experiences of bliss. Wright’s form of enlightenment delivers a different mind-jolt: He makes the compelling case that modern psychological and neuroscientific theories about how our minds work corroborate the Buddhist understanding of how we fail to see our own and others’ wants and needs clearly. Never mind a path to Nirvana, a daily stab at getting distance on ourselves can help. Wright’s mix of conceptual ambition and humbly witty confiding makes for a one-of-a-kind endeavor—instead of a formulaic how-to book, a fascinating why-not-give-it-a-try book. — A.H.

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / W.W. Norton & Company

Robert Wright: My favorite book this year was Draft No. 4 by John McPhee. I have to admit to a bias here. McPhee was my teacher in college, lo these many years ago, and this book is about writing. So part of the pleasure of reading it was being transported back to the seminar room where I first gathered the confidence to try to become a professional writer and where I learned lessons that would aid that endeavor. But the lessons themselves, from a master of the craft, are of value to any student of the craft. He’s a quirky master, a fact that makes the lessons more fun than you might guess on the basis of their common denominator: Write with integrity—in various senses of that word—and with care. Plus, there’s the generous supply of anecdotage you’d expect from someone who has now spent half a century at The New Yorker and who prepped for that gig by writing celebrity cover stories for Time at the height of its powers.

As for books that informed my book on Buddhist meditation: I read a number of classics on Buddhism, such as What the Buddha Taught by Walpola Rahula. But a book that was more valuable than many of them was Paul Bloom’s How Pleasure Works. Bloom emphasizes that the pleasure we get from things depends on the stories we tell about them. Someone once paid $772,500 for a set of used golf clubs and, apparently, got deep pleasure from them. Why? Because they had belonged to JFK. But, strictly speaking, it wasn’t the fact of JFK’s ownership that gave pleasure so much as the belief in it. Had the auctioneer mistakenly shipped a different set of circa-1960 clubs, the buyer would still have perceived a kind of presidential essence in them. Well, what works for pleasure works for pain: It’s often the stories we tell ourselves about things that make them sources of suffering. Mindfulness meditation is among other things a way to undermine these stories. Bloom’s take on the psychology of pleasure helped me see the link between even the more “therapeutic” uses of mindfulness—to sap the energy of anxiety, anger, and so on—and deep ideas in Buddhist philosophy, like “emptiness.”

Poetry

Calling a Wolf a Wolf by Kaveh Akbar

Alice James Books

One of the lovely things about Kaveh Akbar’s immensely thoughtful debut collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, is that its narrator is often in motion in some way, even when that movement amounts to stalled progress. Akbar’s poems—which explore addiction and arrested development and the starts and stops of desire—are psychic travelogues that are tiny and expansive at once. In the titular piece, set in a medical facility, the speaker recalls when it was that the compulsion he’s reckoning with first took hold: “I carried the coldness like a diamond for years … until one day I woke and it was fully inside me.” These are journeys that occur in interstitial spaces—between yesterday and today, or between I could and I will, or between death and life (“a body nearly stops / then doesn’t”). In “Portrait of the Alcoholic With Withdrawal,” I paused on the line “Everyone wants to know / what I saw on the long walk / away from you.” It’s a terrifyingly cogent observation, one that shifts perspective right at the end to emphasize how strangely different a personal odyssey looks depending on whether you’re outside or inside it, or somewhere in between. — J.Y.K.

Ecco / Farrar, Straus, and Giroux

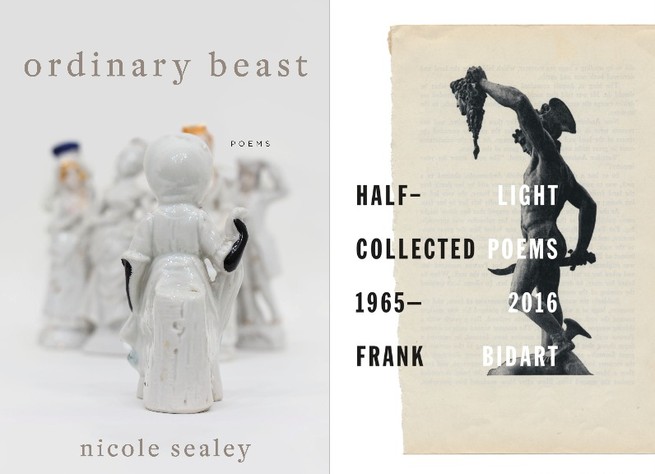

Kaveh Akbar: While 2017 has been an excruciating year for so many Americans, it has also been a historically good year to be a lover of poems. At every turn I found a new bouquet of searching, vital poetry collections to help navigate an increasingly unnavigable living. One such collection, which I haven’t been able to shut up about all year, is Nicole Sealey’s Ordinary Beast. Sealey’s poems are irreducible, almost atomic in that way, with everything orbiting a nucleus of wonder—wonder at love, wonder at grief, wonder at language, history, and mortality itself. A poem called “The First Person Who Will Live to Be One Hundred and Fifty Years Old Has Already Been Born” opens: “Scientists say the average human / life gets three months longer every year. / By this math, death will be optional. Like a tie / or dessert or suffering.” Another, “Object Permanence,” dedicated to the poet’s husband, closes: “O, how we entertain the angels / with our brief animation. O, / how I’ll miss you when we’re dead.” It’s a rending work that alchemizes the strangeness of our being anything at all into exquisite, bone-hard language. The formal flourishes of the book—sonnets, sestinas, one long cento, and a palindromic invented form called the obverse—nod toward history and tradition, while charging headlong into an imagined and more miraculous future. My favorite Sufi prayer goes simply: “O Lord, increase my bewilderment.” Ordinary Beast seems to me a kind of joyous, magnificent reply.

Another book I’ve carried with me on my travels this year is Frank Bidart’s Half-Light: Collected Poems 1965-2016. Bidart has long been a titan of my personal canon, a lodestar poet whose voice and craft have so shaped my own it’s difficult to speak of a specific inheritance. Nobody breaks a line, or writes desire, like Bidart. Holding the entire body of his work at once in a single volume feels a little like holding the skull of a saint; I expect it to start hovering and talking to me at any moment, though I’m always newly shocked when it does. Wherever the year took me, I found Bidart had already been there and knew exactly what to say (and who to employ to say it—many of his best poems are written in the voices of others). While I grappled with the fallout of the U.S. national election, Bidart said: “To further the history of the spirit is our work: / therefore thank you, Lord / Whose Bounty Proceeds by Paradox, / for showing us we have failed to change.” While I worked through a month of bad depression, Bidart said: “Whatever lies still uncarried from the abyss within / me as I die dies with me.” I don’t mean to reduce the volume to its bibliomantic potential, but rather to speak to its breadth and depth and clarity. As one of our greatest ever poets of yearning, he has wanted everything we might want, and recorded that wanting with unprecedented vision. Federico García Lorca said the worst punishment one can endure is to “burn with desire and keep quiet about it.” Thank God Bidart never kept quiet. I don’t know where I would be today if he had.