Buddy Roemer's Overshadowed New Hampshire Retail Experiment (original) (raw)

He's been stumping in the Granite State, but his inability to get any debate time has turned him into the cycle's invisible man.

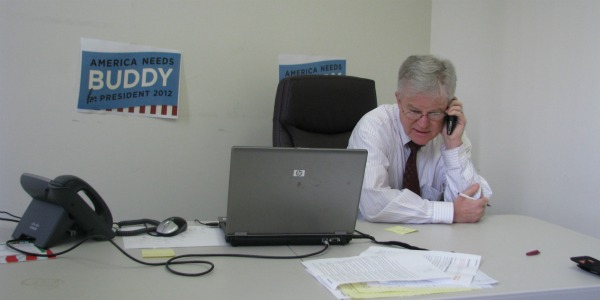

MANCHESTER, N.H. -- The campaign phones were silent.

Campaign volunteers were absent.

The only sound in the second-floor office suite in downtown Manchester was the hard Louisiana drawl of the Republican presidential candidate, as he paced from vacant room to vacant room, talking on a cell phone.

"It's a little hard running against the big boys when you don't have a lot of money," former Louisiana governor Buddy Roemer was saying. "But I'm not giving up because it's an issue that at some point will take center stage."

The issue at hand was the corrupting influence of money in national politics -- and no one has been hitting that issue harder than Roemer on the campaign trail. Big corporations leverage huge campaign contributions to get politicians to shower the companies with trade, tax and spending benefits to the detriment of ordinary Americans, he says.

"We have five or six decent people running," said Roemer in Salem, N.H. "But they won't get the job done because they are slaves to money."

Driving to Salem, he'd pushed the issue: "Some politicians live for service. Other politicians make their living from service. There's a big difference. Newt to me is a classic. He makes his living off politics."

Roemer's anti-establishment views prompted him to become the only Republican candidate to embrace the Occupy Wall Street movement. He is limiting contributions to no more than $100 per donor, not accepting PAC money and arguing that Super PACs are illegal.

That may also be one of the reasons practically no one in New Hampshire or any other early voting state knows Roemer or his message, even though, as Roemer points out repeatedly, he is the only Republican candidate who served as governor and in Congress and has run successful businesses.

That, and the debates.

"I have no poll standing because nobody knows I'm running because I haven't been in any of the debates," said Roemer. "It's like a Catch-22."

Roemer hasn't given up hopes of getting invited to a debate and making a splash in New Hampshire's Jan. 10 primary. (He is skipping Iowa.) But he's also already signaled a back-up plan. He will compete for the unity ticket nomination of Americans Elect, which is promising to field a third party candidate in 2012.

Sixteen years after he last appeared on a ballot, the 68-year-old Roemer thought he had a winning strategy for the Republican primaries. It would mirror his under-funded 1987 governor's race, when he rocketed from last to first in the campaign's final weeks, propelled by a throw-the-bums out crusade that won him a slew of newspaper endorsements and energized voters eager for dramatic change.

Roemer figured he knew how to update his appeal because he campaigned throughout New Hampshire four years ago for his close friend, Sen. John McCain.

Roemer thought he'd gradually build a following by moving to the state and appearing before any group that would have him. He would run against the system but stand out because he had never been part of it. He would attack even Republicans ("Bailout George," he calls President George W. Bush). He would catch everyone by surprise, just as he had done in Louisiana 24 years ago.

Instead, debates have crowded out retail campaigning in New Hampshire this cycle, foiling his strategy.

"Four years ago, there were three debates during the primaries," Roemer said, shaking his head in between bites of a BLT on wheat at a Manchester sandwich shop. "This is different, man."

Republicans have held 16 national debates this year, and Roemer has been invited to exactly none, either because he didn't register in the polls or hadn't raised enough money to meet the threshold for a credible national candidacy required by the debate sponsors.

"I would have had a different strategy if I had known eight months ago what I know now," he told three reporters in Salem, as he waited for the arrival of what would be a crowd of 10 business people.

"I would have made a case to get in the debates. I certainly thought I'd be invited to all the debates. Herman Cain had nothing but debates and a couple of PACs. Everything is debate-centered."

Roemer's voice rose with passion and indignation.

"It affects your credibility. It affects your fund-raising. It affects your poll numbers. It even affects whether you get in other debates."

Roemer paused.

"That's powerful," a reporter/camerawoman from the Salem Community TV station said loud enough for others to hear.

* * *

Charles Roemer III grew up on a cotton farm in north Louisiana and was nicknamed Buddy as a boy. He was his high school valedictorian and went to Harvard University at age 16. He stayed to graduate from Harvard Business School.

Roemer was an anti-spending four-term Democratic congressman in 1987 when he and two other congressmen challenged the state's catch-me-if-you-can Democratic governor, Edwin Edwards. Roemer broke with tradition by refusing to accept cash contributions.

He catapulted over the others with the same tough-talking, plain-spoken appeal that he is making today.

As governor, Roemer first got the legislature to end unlimited campaign contributions. At his bidding, it also raised teacher salaries, required teacher evaluations, plugged a massive budget deficit and toughened enforcement against the state's notorious oil and gas polluters.

But voters rejected his plan to revise Louisiana's tax code. The legislature stalled his reform agenda. Enemies pounced, calling him arrogant, snide and sanctimonious. In the meantime, Roemer's wife left him, taking their 10-year-old son. Roemer seemed to lose the will to fight.

He embraced a New Age adviser who told the governor and his aides to wear rubber bands and say, "Cancel, cancel," every time they had a negative thought. Pundits belittled him.

In 1991, Edwards mounted a comeback bid from the left. State Rep. David Duke, a smooth-talking former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard riding a wave of white resentment, challenged Roemer from the right. Roemer switched to the Republican Party and ushered in legalized gambling in Louisiana.

In what locals dubbed the Race from Hell, Edwards and Duke knocked Roemer out in the open primary before Edwards went on to defeat Duke.

Roemer ran for governor again in 1995. After leading much of the race, he faded to fourth.

A banker before he entered Congress, Roemer founded a community bank, sold it and made a pile of money.

In 2006, he started Business First Bank in Baton Rouge. Under his watch, it has grown to more than $500 million in assets.

"We didn't foreclose on a single mortgage holder," Roemer said in Salem. "We didn't take any bailout money. I've been creating jobs."

He scanned the crowd sitting at the square table. "I don't need a job. I've got a life. But I think we're in trouble."

C.B. Forgotston, a prominent political blogger in Louisiana, said Roemer's presidential campaign is invisible even at home. Those aware of it, Forgotston added, often ridicule it as a Hail Mary bid.

Roemer doesn't chafe at this view. "They laughed at me (in 1987)," he said and added, "I don't really care what they think. It's easier at 68."

Without complaint, Roemer spent an hour on a recent afternoon calling producers of political talk shows to ask that they'd consider giving him air time. Several phone clerks transferred him straight to voice mail.

During the Republican debates, Roemer watches on TV, shouting out his answers and asides to two aides who send out a stream of tweets under his name.

His zingers have won a following, and become part of the campaign cycle's meta-conversation, such as when he mocked Texas Gov. Rick Perry during a debate after Perry couldn't remember the third government agency he would abolish. Roemer remembered it before Perry did.

Matthew Krawitz, who Tweets at @NEFreedomRide, attended a Roemer campaign appearance at the Boston home of Lawrence Lessig, a Harvard law professor and author of a just-published book that attacks big money in politics.

"I love that he is comfortable enough with his message that he can banter and joke on what's happening around him," Krawitz said of Roemer.

And cable TV hosts prize Roemer during his infrequent appearances.

In late November, Roemer captivated Joe Scarborough on his MSNBC cable show by declaring, "Look at Obama. All that hope and promise. No changes....Guess who he's raising (money) from? The very banks he's supposed to regulate. He went to Wall Street, had a fund-raiser. $35,800 a ticket. And you know who the host was? Goldman Friggin' Sachs."

Laughing, Scarborough proposed that Roemer be an honorary member of Morning Joe's Round Table.

And Stephen Colbert broadcast a fake ad featuring Roemer that lampooned the supposedly independent nature of Super PACs.

Roemer says he feels a small gust at his back because he has begun broadcasting his first TV spot and will soon qualify for matching public funds. He will use that money -- and a forthcoming social media strategy that he won't yet reveal -- to try to score a burst of last-minute attention that will lift him above the 5 percent qualifying cutoff for the final New Hampshire debates.

Andy Smith, director of the University of New Hampshire's Survey Center, says that he expects Roemer will remain a fringe candidate.

"Once you get in that hole, it's hard to get out," Smith said.

Roemer knows, so he has announced that he will likely compete for the nomination of Americans Elect, a web group that will choose a candidate through an online vote in June and promises to put that candidate on the ballot in all 50 states.

Mark McKinnon was Roemer's press secretary in the 1987 race and went on to serve as President Bush's media adviser in 2000 and 2004. Now on the advisory board of Americans Elect and deeply dismayed with Washington, McKinnon said he thinks that Americans will listen to a third-party message. "All kinds of indicators of faith in parties and institutions are at an all-time low," he said.

McKinnon believes that Roemer can appeal to the right with his anti-spending message and to the left with his attacks on big banks and money in politics.

"Roemer ties together a left-right coalition," McKinnon said. "I think that the Republican Party will regret not embracing him because he'll have an impact as a third party candidate."

Image credit: Tyler Bridges