Margaret Atwood introduces Graeme Gibson’s Perpetual Motion and Gentleman Death (original) (raw)

Margaret Atwood and Graeme Gibson stop on the red carpet at the Scotiabank Giller Bank Prize gala in Toronto on Nov. 19, 2018.Chris Young/The Canadian Press

Excerpted from Gentleman Death/Perpetual Motion_. Copyright © 2020 by Graeme Gibson. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved._

Supplied

The first time I sat down to talk with Graeme Gibson, in 1970, I read his hand, as I was in the habit of doing for strangers in those reckless days. “Everything is connected to everything else,” I said sagely. “Your intellectual and creative selves are continuous with your lifeline and your fate line. It’s all one.” And so it was, and so it would be.

Fleeing the city and the complexities of a crumbled marriage, Graeme moved to a rented farm near Beeton, Ont., that year. I visited off and on, and then off, and then on. We were both working with the newly founded small publisher House of Anansi Press – I say “working” loosely because it was a young writers’ press and nobody got paid very much. I was editing Graeme’s book Eleven Canadian Novelists – radio interviews with writers that he’d done for Robert Weaver’s CBC show Anthology. It was my job to hack a pathway through the transcripts: They’d been typed up by a woman who turned out to be somewhat deaf, so I had to guess what the writers might actually have said.

When we weren’t busying ourselves with such publishing tasks, we were trying to arrange a life together. The man who owned the Beeton farmhouse wanted us to buy it, but someone had cut a piece out of the main beam of the old barn and stuck it over the fireplace – meaning that the barn would soon collapse – so we looked elsewhere. We didn’t have much money, but we finally found something we could afford: an 1835 farmhouse, uninhabited, uninsulated and, unknown to us at the time of purchase, haunted.

Having raised the sagging floor and discovered a big pile of well-rotted manure in the barn suitable for a vegetable garden, we settled down to write, more or less. Graeme was at the same time organizing the Writers’ Union of Canada and taking various literary odd jobs to make a semblance of an income, and on weekends and holidays we usually had a houseful of hungry people: his teenage sons, their friends and friends of ours on restful outings from the city, all of them joined midway through the 1970s by our newborn daughter. We had two stoves: a wood-burner, on which a cauldron of something was eternally simmering; and an electric one, with an oven suitable for reviving half-dead lambs. We had a washing machine of sorts but no dryer. Various of our preserved foods exploded in the root cellar. I won’t go into the matter of the sauerkraut, except to say that we should have made it outdoors.

In the midst of this intermittent chaos, Graeme wrote on, somewhat more than I did at the time, in fact. His first novel, Five Legs (1969), had done surprisingly well for such an experimental work; his second, Communion (1971), was a succès d’estime, but at the end of it he’d killed off Felix, the young man who’d first appeared in Five Legs. Now he was casting around for his next focal point. During this period, several proto-novels came and went; they would be started in a fire of optimism, then shelved when they failed to engage Graeme fully. He was an all-or-nothing kind of man.

Graeme was a person not only of enthusiasms but also of moral imperatives. He decided that since we had a hundred acres of weedy farmland, it was our duty to farm it. He didn’t want to be a city person lolling about idly in the country; he wanted the immersive experience. Needless to say, neither of us had ever spent time on a farm before. At auctions he acquired a second-hand baler and a harrow to go with the old tractor that had come with the property. What we grew on our rolling acres was alfalfa. Graeme later said that farming was driving around until something broke, then driving around to find the part to fix it, then driving around ...

We also accumulated an assortment of non-human beings. “What kind of animals should we have?” Graeme had asked an old farmer at the outset. “None” was the answer. Then, after a pause: “If you’re gonna have livestock, you’re gonna have dead stock.” And so it was, and so it would be. Things died. Sometimes we ate them.

We had chickens, for which Graeme built a henhouse and an enclosed yard; an old horse, which the poet Paulette Jiles had persuaded us to rescue; some ducks because we had a pond and what was a pond without ducks? Another horse, to keep the first one company; and some jumping cows whose escapes were the marvel of the neighbourhood; and a couple of geese that got stepped on by the cows and then eaten; and then – why? – some sheep, which had a habit of dying of gid or almost drowning in the pond; and, to round off this Noah’s Ark, a pair of peacocks.

The peacocks were for my birthday. They added unearthly screams to the ambience, which by now was quite Gothic. I won’t go into our attempt to raise chicks in an incubator – you have to get the temperature just right, and we didn’t, and Frankenchicks is what came out – nor the sad tale of the male peacock, who was deprived of his peahen by a blood-drinking weasel and went mad and became a mass murderer of the hens.

Thus began Perpetual Motion, Graeme’s tale of pioneer farming set in a house strangely like the one we were living in and on a piece of land oddly like ours. The protagonist, Robert Fraser, is a man of enthusiasms, like Graeme, and his frustrations and crackpot obsessions have at least a cousinly relationship to Graeme’s. So do the black flies and thunderstorms and recalcitrant cows that plague him.

But although some of the incidents and details are immediately recognizable to me, not everything in the book came from personal experience. Graeme combed through dictionaries of slang and unconventional usage to make sure his characters were using words they really would have used, unpleasant though modern tastes might find some of these. He consulted local histories – what was going on in and around Shelburne, Ont., in the early to mid-19th century? What had the people who’d settled the area been like – those from whom many in Ontario were descended, including Graeme? Not always very savoury, the novel tells us.

The digging up of the bones of extinct giant animals and the exhibiting of them was a much-publicized pursuit in the 19th century, and Southern Ontario was a hot spot for mammoths, Graeme discovered. So it’s not anachronistic that Robert Fraser unearths such a skeleton, nor that he hopes to profit by it. Public interest was high, as was controversy: Such animals were a challenge to the prevailing biblical narrative. Were these beasts dragons that had perished in Noah’s Flood, and if not, what were they? Fraser’s excavated mammoth bones set the keynote for the novel; as the mammoth went, so might we overweening humans go, was the subtext.

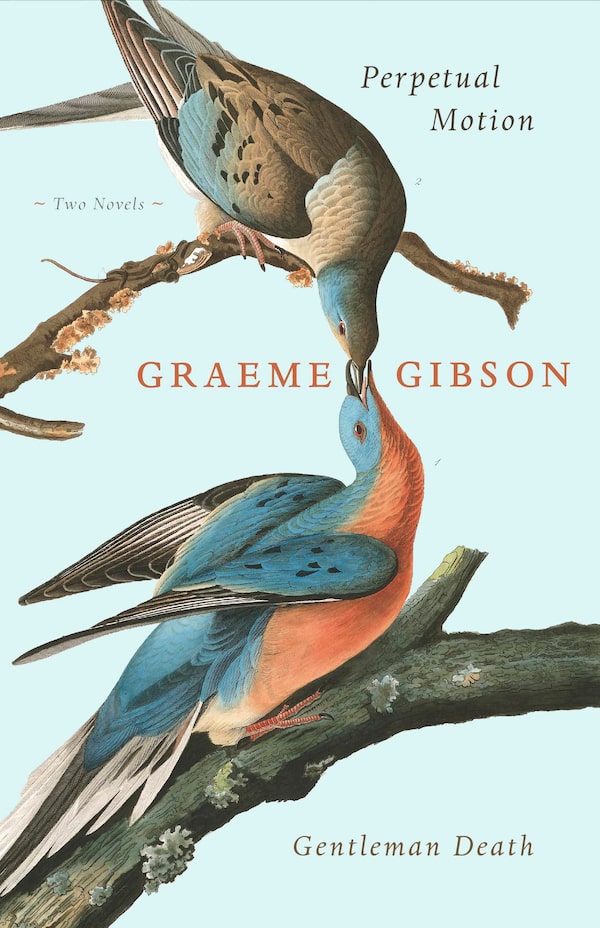

Then there was the history of the perpetual motion machine, that alluring but impossible Holy Grail sought by many inventors in those times, and the huge flights of passenger pigeons – so damaging to crops – and the money that could be made from slaughtering them. The search for perpetual motion and the extinction of the passenger pigeon were based on the seemingly incurable human hope that there is indeed a free lunch eternally available on this Earth. Nature’s bounty – here in the form of pigeons – will never run out. The first law of thermodynamics can be cheated. It’s a delusion, but one that persists to this day.

The Gibsonian style is difficult to describe. Hesitations in speech and thought, doublethink, expletives and spluttering, the tics and tricks of verbal communication and the failures to communicate: These are present to a greater or lesser extent in all of Graeme’s fictions. Farce and antic dispositions and human stupidity and nobility and futility and tragedy are never far apart, though tempered with a sort of loony cheerfulness. The last word in Perpetual Motion is “moon,” a Western symbol for illusion and deception. But despite the explosion of his crazed machine, Robert Fraser does not give up; he continues the “desolate search” for something that – try as he might, plausible though he may sound in his efforts to convince others – does not exist.

Graeme almost didn’t finish Perpetual Motion because three-quarters of the way through it he nearly died. In mid-November of 1979, I was in Windsor, Ont., doing a book event, and when I got back to my hotel room there was a message waiting for me. It was from our friend and neighbour Peter Pearson – the filmmaker – who was standing watch in the hospital in Alliston, Ont. Graeme was in the operating room. He had a ruptured duodenal ulcer, which, given a few more hours, would have put an end to him. Eight weeks later, though still wobbly, he was back on the fictional track. He worked on the novel during the two or three months he spent in Scotland while I was holding down the farm with help. Shortly after this, we moved back to the city, a choice for which Graeme’s near-death and weakened condition were only some of the reasons. Perpetual Motion was finished and published in 1982, with translations into French, Spanish, German and, as I recall, Polish.

Graeme’s near-death was a hint of what was to happen in his life during the 1980s. His father, Brigadier-General T. G. Gibson, died in the middle of the decade, and his younger brother, Alan Gibson – a film and television director in England – followed in 1987. (His mother had died earlier, in the mid-1960s.) These deaths, his own near-miss and the fact that in the natural course of events he himself would be next in his family to go – a fact of which he was more than aware – were the impetus behind his fourth and final novel, Gentleman Death (1993).

It’s a curious book; but then, which of his books was not? It begins with a novel being written half-heartedly by a moderately successful novelist strangely like Graeme. This comically unsatisfactory novel bears more than a passing resemblance to some of those that Graeme himself had cast aside. The real-life novelist is called Robert Fraser, like the protagonist of Perpetual Motion, and is clearly a descendent. Does novel-writing have the same place in the mental life of Robert Fraser the Second as the search for a perpetual motion machine had in the life of Robert Fraser the First? Is it too a delusion, a clutch at the moon? Possibly.

Robert Fraser’s novel weaves in and out of Robert Fraser’s life, and his memories and dreams inform both. The memories of his childhood during the Second World War are absolutely Graeme’s. His mother’s struggles as a woman left to cope with two boys during the early 1940s, her depressions after her hospital visits to soldiers mangled by the war, his own fears about his overseas father as the fathers of his friends were killed one after another – we in the family remember him describing these events in much the same words as those used by Robert Fraser. The illness and death of his beloved brother, his grief and loss – these too are in the book. His battles with his father, then his caretaking as that father ages, becomes frail and starts seeing people who aren’t there – all of it happened as described. Robert’s quizzical attempt to come to terms with mortality, his experience of ghosts and his dreams of the departed, his recognition of the death’s head behind his own face – these too were Graeme’s. They are also widely shared human experiences, although each of us experiences them in our own way.

No spoilers, but Graeme’s protagonist does achieve an equilibrium of sorts. Living in the past, however unhappy that past may have been, is a protection against the knowledge of our own mortality, since in our past we ourselves are always alive, no matter how many around us have died, and to live in the present is to accept our inevitable death. Yet if you aren’t alive to the present, how can you live your life to the full? Death the Gentleman waits for us all, not outside us but within us; our secret sharer, and in a sense our friend, for what would life be if we were doomed to live forever? “Here it is at last, the distinguished thing,” Henry James is said to have said on his deathbed, a quotation with which Graeme was familiar. Robert Fraser is not completely Graeme, of course; but, as I’d said when I’d first met him, his creative life and his real life were one.

What of the flirtations of Robert Fraser? Were those also from Graeme’s actual life, you may wonder? Search me. I myself seem to be in the book too, although I’ve been given quite a different body. Names have been changed to protect the innocent, to no avail as usual.

After Gentleman Death, Graeme attempted one more novel. It was to be called Moral Disorder and was entangled with his experiences at PEN Canada, dedicated to supporting writers imprisoned elsewhere in the world, and with World Wildlife, alert to habitat destruction. It also registered his increasingly horrified view of politics and cynicism and venality and the way things were going, particularly in relation to the natural world. He wrestled with this novel for a time – he was not an easeful writer, he couldn’t just turn things out – but he failed to convince himself and abandoned the project in 1996. I asked him for the title – it’s pleasingly suggestive – and used it for a book of short stories, so that much at least of this lost book survives.

By this time Graeme was deeply in the world of birds, on several levels. (It will not have escaped notice that Perpetual Motion is the work of a proto-environmentalist.) As I’ve said, he was all-or-nothing, and his enthusiasms were consuming. The result, eventually, was The Bedside Book of Birds, which took 10 years to get published – initially publishers did not grasp either the concept or the public hunger for engagement with the avian world – and finally appeared in 2005. It’s a miscellany – a collection of the ways in which human beings have interacted with birds, always and everywhere, through myth, art, literature and science – with each section introduced by a personal essay.

BBB, as it was known in his filing system, sold more than any of Graeme’s other books and brought in an avalanche of letters from grateful readers. It was at one with his life, as was all his work. Had Robert Fraser the Second started earlier, he might well have been an ornithologist, as Graeme himself frequently said he wished he had been. But as he was also in the habit of saying, “What might have been is an abstraction.”

He was what he was.

Or, rather, he is what he is.

Margaret Atwood, February 2020.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.