Malcolm X’s autobiography didn’t change me, it saved me | Lemn Sissay (original) (raw)

Were Malcolm X’s autobiography to be published today, would it be called “hate speech”? Would he be blindfolded and shackled, dressed in an orange jumpsuit, and imprisoned in Guantánamo Bay? What’s certain is that its subject matter, first published in 1965, would be branded extremist, and most probably terrorist.

I read this book aged 17, when the word Muslim wasn’t used as a threat to the status quo, and it helped me understand 20th-century America: without Africans, it made me realise, there would be no America. Since then, it has travelled with me throughout my life and feels even more resonant now than it did when I first read it. But back then I needed it. I needed it bad.

I was on the verge of leaving the care system for a world of who knows what. I felt like a laboratory experiment about to be released. I had been told lies about myself. People told me they were colour blind when in fact they saw my colour. People insisted “we’re all the same” – when in fact they noticed my difference. And so it was logical that the more they said, “we are all human beings”, the more I questioned whether or not they viewed me as human.

All I could feel was their fear. The laughing colourless boy turned into a shocked watchful black man who felt more “human” than ever before. There are parallels in sexism. Imagine a woman says she is a woman only to be told: “No, luv, you are wrong. You are not a woman, you are a human being.”

It’s not so much the book that changed my life as the book that saved my life. This autobiography does not just bear witness to racism. This is a book about humanity and human failings and how to rise through and beyond them. In 1990, Charles Solomon wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Unlike many 60s icons, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, with its double message of anger and love, remains an inspiring document.” It’s a page turner too. This magnificent and gripping story was all the evidence I needed that I was not alone.

The title of the first chapter is Nightmare. After his house is torched by the Ku Klux Klan and his mother incarcerated for mental illness, the young Malcolm became a foster child.

Malcolm Little was the only black boy at his school. “As the ‘nigger’ in my class I was in fact extremely popular,” he writes. “I suppose partly because I was kind of a novelty. I was in demand”.

Malcolm X refers to his grandfather as “the rapist”. Slavery had raped its way into his DNA. Interestingly, this passage struck a chord with Barack Obama. In 1995, the year his own memoir, Dreams from My Father, was published, the future US president said: “I imagine myself following Malcolm’s call. One line in the book stayed with me for he spoke of a wish that he once had. The wish that the white blood that ran through him, there by an act of violence, might somehow be expunged.”

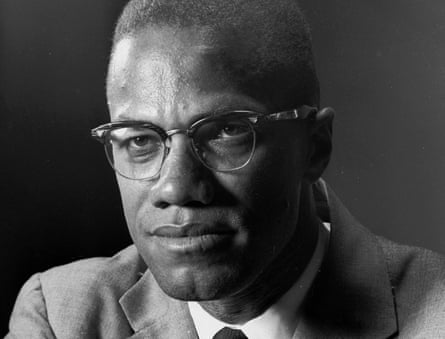

‘Being immaculately dressed and running on the dark side of society, imprisonment wasn’t long in the waiting for Malcolm.’ Photograph: Eddie Adams/AP

Several of the characters in The Autobiography of Malcolm X are fledgeling pimps, including Malcolm himself. But the figure of the pimp is also something of a hero, in the same way Dick Turpin and Robin Hood were heroes: he beats “the man”. Being immaculately dressed and running on the dark side of society, imprisonment wasn’t long in the waiting for Malcolm. But he didn’t serve time in prison as much as time served him. He was introduced to Islam by his brother, and took up one of its central instructions: to read. His intelligence found its conductor like a lightning bolt finds the Earth. This lesson of reading was happening to me as I read about it happening to him.

The English canon offered me nothing on the experience of being black. It was apparent to me that I was deliberately blocked out; and so I sought out other more human narratives only to return to the canon later.

Alex Haley, on whose interviews with Malcolm X the book is based, did a masterful job of editing the transcripts, and his long introduction is worth the cover price alone. After reading The Autobiography, I later took up Walter Mosley, Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Paul Laurence Dunbar, the Last Poets, Gil Scott-Heron and Langston Hughes. Toni Morrison said: “All paradises, all utopias are designed by who is not there, by the people who are not allowed in.” On reading Malcolm X a door opened. I was allowed in.