Poison pass: the man who became immune to snake venom (original) (raw)

Sometime in 2006, when my ex-boyfriend failed to show up for dinner, I assumed something was wrong or perhaps he’d forgotten. About a week later, calling to apologise, he told me he’d had an overdose, accidentally injecting a lethal cocktail of venom from three snakes. A lot has been written about Steve Ludwin, widely known as the man who injects snake venom, and lately his life has turned into a non-stop frenzy of international journalists and film crews revelling in the seeming sheer insanity of it.

Steve was once my great love; an animal lover, vegan and musician who wrote songs for Placebo and Ash, and played the Reading festival with Nirvana. In between tours and recordings he dabbled with snake venom. In his latest incarnation as a self-taught snake expert, moulding himself into the role of a lifetime, he appears as a kind of living specimen and star in a short film at the Natural History Museum’s new exhibition, Venom: Killer and Cure.

“How cool is that? You normally have to be dead or a fossil to be in a museum,” says Steve, now 51, as we sit in his in Kennington flat, with its roof terrace offering glimmers of the London Eye and Parliament. He lives there with his Australian banker girlfriend Suzy, Russian blue cat Pushkin, a rare iguana and several snakes.

He’s been shooting, swallowing and scratching venom into his skin from some of the world’s deadliest snakes for 30 years. “Snakes are fucking everywhere. The symbol for medicine is two snakes. They’re ingrained in our brain and DNA,” he tells me, proudly insisting that he hasn’t been ill for decades and has developed “a superhuman immune system”. And it’s tempting to believe him. He does look undeniably fit.

The first time he did it was in October 1988 and he showed me his swollen wrist. I refused to indulge him and thought he was stoned. Today, Steve laughs at the memory. “Not really… well maybe,” he says. “But you know I’ve always loved snakes. I had no idea what it would do to me, but I knew it’d been done before and was curious to see if it was possible to become immune to snake venom.”

‘You know I’ve always loved snakes’: Steve Ludwin holding an iguana with Britt Collins, shot at Steve’s home in London Photograph: Pal Hansen/The Observer

Now, ironically, Steve is on the cusp of something monumental, the development of a human-derived anti-venom that could potentially save many thousands of human and animal lives.

“When I was 17,” he says, “I knew I was going to inject snake venom in the future. I felt like Richard Dreyfuss in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, when he had that feeling ‘this means something’. It took many years and accidents of messing around with it to finally make sense.” He looks down at his arms, showing the maze of track marks. “I look like a junkie. You can see all the incisions.”

After university, Steve and I lived in Islington with our cream-tabby cat Tad and a couple of friends. Our house was a zoo, with our potbellied pig Lou who loved the Velvet Underground, a ginger-and-white rat Moo-Moo whom I saved from the fangs of a copperhead, a pair of rescued iguanas, a vicious baby caiman crocodile and a terrifying assortment of snakes and scorpions. But for us, to live among wild animals was all we ever wanted. While pursing his music career, Steve had his dream day job, handling reptiles at the Vivarium in Walthamstow. The pet shop had a back room with venomous snakes. And it wasn’t long before he began bringing home rattlesnakes, copperheads and vipers with enough venom to kill our entire street.

I started an indie-music glossy called Lime Lizard and everyone and their mates showed up at our Victorian terrace, turning it into a den for drugs, debauched rockers and deadly snakes. Inevitably there were accidents: a fugitive snake that reappeared through the floorboards eight months later; diamondback rattlers left carelessly beneath a baseball cap on our bed that our flatmate nearly sat on. I got bitten by a tarantula that left me swollen, bruised and hallucinating for days, and almost crushed by a boa constrictor after Steve draped it around me for a photo.

Steve and I met in February 1986 at Eckerd College, a small liberal-arts school on a sun-struck sliver of Florida coast. I was there as a transfer student from UC Berkeley for my one and only semester. I lived in the same co-ed dorm as Steve. One evening, walking back from dinner, I heard New Order’s Temptation blaring from his room and started dancing outside his window. We took one look at each other and that was it. He looked like the all-American boy – tall, lithe, chiselled, with a floppy fringe and faint dusting of freckles – except he was anything but. Steve was born on an air force base in Los Angeles. His father, Ray, was a pilot for Pan Am, who met his beautiful Canadian mother, Jacqueline, when she was a stewardess. Growing up with two sisters in New Milford, a sleepy Connecticut town, he lived next door to Eartha Kitt, the original Catwoman in the 60s Batman TV show. I knew Steve was a stoner, but he was funny and engaging, had a cool New-Romantics haircut and great taste in music. I remember being struck by his handsome face, his quirkiness and intensity: he believed in aliens, the deep state and punk as a philosophy. That night we went to a smoky indie club, dancing to the Violent Femmes and Psychedelic Furs until 4am and skipping morning classes. That was the start of our love affair and deep and enduring friendship. Neither of us realised it then, but it was a really romantic time.

On our second date, sitting on his bed, I felt something brush against my ankle and thought: “Perfect, he has a cat.” Glancing down, an 8ft boa, thick as a motorbike tire, slithered from under the bed. I screamed and shot out of his room.

When Steve calmed me down, taking my hand like a small child and showing me the satiny-softness of the boa, I lost my fear of an animal that had previously terrified me, and eventually fell in love with lizards, too, even naming my magazine after them. At the end of term, Steve was keen to show me Costa Rica, where he’d lived as a student. Soon enough, we found ourselves alone among iguanas, parrots and howler-monkeys on the deserted beaches of Manuel Antonio, traipsing bare-legged through remote rainforests filled with ultra-territorial predators like jaguars and pumas, and the baddest killers on earth: toxic frogs, spiders and snakes like the deadly bushmaster, which I nearly tread on, and crossing into Nicaragua to see the sea turtles in Tortuguero during the Sandinista-Contra conflict that was terrifying to everyone but us. Before we even got on the dodgy fisherman’s boat from Limón, we could hear gunfire and mortars exploding in the distance. Steve, unfazed, said, “Fuck it, we have to die sometime,” and I went along for the adventure. Steve bought a T-shirt off the back of a Sandinista rebel for $50. Like many college kids steeped in left-wing politics in Reagan’s America, we were rebelling against the pervasive conservatism and generation that ran our lives, searching for something authentic.

‘On our second date I felt something brush against my ankle and thought, perfect, he has a cat. An 8ft boa slithered from under the bed’: when Britt met Steve, back in the 80s

Our arrival in London happened to coincide with the late-80s underground scene exploding with bands like the Stone Roses, which for our generation felt like the 60s. Steve and I stayed together for seven mostly happy years and I remember it vividly – the gigs, stage-diving to Mudhoney and the Pixies and dancing at the Syndrome, an after-hours club on Oxford Street, hanging out with bands like Ride and Blur.

When Steve was “unsure what to do with the rest of his life” at 20, I encouraged him to pick up a guitar and write music. Months later, he auditioned for My Bloody Valentine. Inspired by the Beatles, REM and Black Flag, he started several semi-successful indie groups before landing a million-pound deal with Island Records with his band Carrie.

When an unscrupulous music-industry figure stole my magazine Lime Lizard, I was so crushed I couldn’t get out of bed for a month. Steve, in his laid-back way, said: “You have three choices: either you rot in bed like Brian Wilson; we can pay Bradley [one of his rough East End gangster mates] to break his legs; or you forget about it and create something else. Why don’t you write a book about your favourite band Nirvana, you know they’ll be huge?” I knocked out a proposal and asked my best friend Victoria Clarke, who was a little lost at the time, to write it with me. We instantly found an agent and a big publishing deal in 1991, before Nevermind was released.

As Steve and I were finding our way into adulthood – between the daily grind, drugs and groupies (he had crazed Japanese fans showing up on our doorstep at all hours, leaving love notes and giant teddy bears that terrified our cat) – our relationship ran its course. But we remained friends long after breaking up.

Steve was always insanely restless and curious and, in some ways, wilfully destructive. So I was hardly surprised when he had his venom overdose. He initially refused to go to hospital, fearing his snakes would be taken away. Instead, he sat down to watch David Attenborough’s series Life in Cold Blood about reptiles, over a Chinese takeaway, while his hand blew up into the size of baseball mitt. “I started thinking: ‘Wow, this is crazy. I could easily die here,’” he says, remembering feeling a pain with the intensity of “being stung by a thousand bees”.

Lethal shot: Steve milking venom from a pope’s pit viper. Photograph: Pal Hansen/The Observer

“But I was happy and didn’t care,” he adds. “I’d had such a great life. When they say your life flashes by, I saw all the good bits and felt them, all the rock’n’roll moments, every great gig I went to or played. This is what intrigues me about snake venom, that scientists say there are compounds in certain venoms that help its victims accept and relax into death. I felt that first-hand.”

The next morning the swelling had worsened. “My arm was all red and doughy with a sack of liquid hanging from it and I could see the blood vessels appear. It was like something out of Evil Dead. It’s evolution telling you to stay away. Why do you think monkeys, dogs and everyone is instinctively scared of snakes?”

When he finally went to hospital, the NHS doctors had never treated a snakebite victim, let alone someone with the venom of three different snakes coursing through their bloodstream. “They didn’t know what to do,” Steve says, when he had to tell the stunned A&E nurses he deliberately injected himself. The doctors put him on the phone to a renowned snake expert, who Steve recalls telling: “‘I used a Northern Pacific rattlesnake, an eyelash viper and a green tree viper from Asia.’ And he just said: ‘Well, you’re screwed. There isn’t an anti-venom because you used three different species.’ Then he said: ‘You’re probably going to die or, at best, lose your arm.’”

The doctors suggested “cutting his arm wide open in a fasciotomy” to release the pressure. “I said: ‘Fuck that, I’d rather die.’ The snakes that I used had a hemotoxin, which destroys red blood cells, and that’s why people’s legs and limbs fall off in Central America.”

They gave him the anti-venom CroFab to target the rattlesnake venom that most likely caused all the problems. After three days in intensive care with no improvement Steve, pulling out his IV, discharged himself. Contrary to all their dire predictions, his hand, aside from the bruising, was back to normal a week later. “The doctors were shocked when I went back. They’d never seen a recovery like it. I thought: ‘Cool, this shit’s working.’”

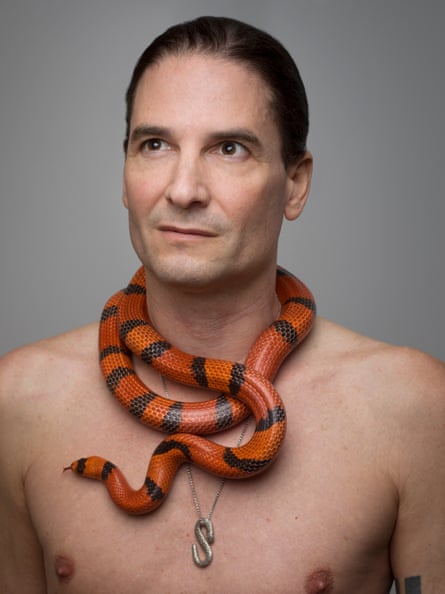

‘You could ask me why I’m continuing to inject. But my drive now is to come up with other ideas’: Steve Ludwin. Photograph: Pal Hansen/The Observer

Convinced his miraculous recovery was down to his self-immunisation, Steve became more fervent. He cheerfully admits mixing black mamba, cobra and puff-adder venom like the ingredients of an exotic cocktail and then, dizzied on pain and adrenaline, skateboarding through London traffic. “It made me feel invincible,” he says. “I was living like a madman. It got to the point where I was injecting almost daily, my legs, all over my body because you don’t want to do a lot of damage in one area as it could destroy nerves.”

He had literally turned himself into a science experiment, but there was a point to his madness. “For the past four years, I’ve been flying to Copenhagen to give blood and last year I had a bone-marrow operation. They drilled into my lower spine to take out bone marrow. It took me two months to recover.” Researchers at the University of Copenhagen have recently created an artificial library of antibodies, the Ludwin Library, generated by Steve’s immune system in response to the toxic injections, to develop the first human-derived anti-venom.

“What most people don’t realise is that anti-venom has been taken from horses’ blood for more than 100 years and sometimes snakebite victims die anyway, because their bodies reject it. When I walked into one of those blood farms and saw about 60 horses with holes in their necks being injected with venom, and with massive bags draining out blood, I was very emotional, knowing what they were going through.”

The World Health Organization considers venomous snakebites among the most neglected tropical diseases, killing more 125,000 people a year. “Anti-venom is very expensive. Pharmaceutical companies see it as a developing-world problem and have slowed the production, so snake fatalities are rising. These Danish scientists will solve that problem quickly by using technology and having found an idiot like me who spent decades injecting himself.”

His audacity and inventiveness is part of Steve’s appeal. “You could ask me why I’m continuing to inject. But my drive now is to come up with other ideas. People don’t self-experiment enough. Scientists are now saying using toxins, if you get it right, can have beneficial side effects to your body that slow ageing. It’s like a Jane Fonda workout video for my immune system.”

“I’m the happiest I’ve ever been,” he reflects, cranking up Adam Ant’s Puss ’n Boots and grabbing Pushkin, who’s high on catnip. He wanders out on to the terrace, lifting the cat over his head to show him London. “If those scientists win the Nobel Prize for medicine and I get recognition, that would be sweet.”

Venom: Killer and Cure is at the National History Museum until 13 May. See Steve behind the scenes at nhm.ac.uk/discover/the-making-of-venom.

Strays: A Homeless Man, a Lost Cat and Their Journey Across America by Britt Collins (Simon & Schuster) out 26 June 2018