Kerslake findings: emergency responses to Manchester Arena attack (original) (raw)

Fire service

The Kerslake report was initiated last September by Greater Manchester’s mayor, Andy Burnham, after he was contacted by “immensely frustrated” firefighters who had been ordered by their superiors to move away from the arena rather than towards it. The firefighters heard the explosion from their base at Manchester Central fire station, which is just 0.6 miles from the concert venue, but they were ordered to drive three miles north of the city centre to Philips Park, another station.

They turned on the TV to see colleagues from the police and ambulance service at the scene, Burnham told reporters on Tuesday, but were still told by the officer in charge of the fire service response that it was too dangerous to deploy. They believed a marauding terror attack was under way and national protocol said they should keep their distance. It was two hours before they were allowed into the arena – when their usual response time is six minutes. It was a decision Burnham described as “right on paper but wrong in practice”.

Peter O’Reilly, the chief fire officer on 22 May last year, decided not to go to the arena that night, going instead to the fire service headquarters in Swinton, five miles away. He took early retirement in September on a full pension. His successor, Dawn Docx, said no one had been disciplined as a result because she was more interested in learning than blaming. Burnham said on Tuesday that it wasn’t fair to “scapegoat” one individual but that he had commissioned a “whole service” review into the culture and practices of Greater Manchester fire and rescue service.

Police

Greater Manchester police (GMP) was largely praised by Lord Kerslake for its response to the attacks. But areas of learning were identified. The force failed to tell other agencies – notably the fire and ambulance services – that it had declared Operation Plato, the agreed operational response to a suspected marauding terrorist firearms attack. The force duty officer believed a Paris-style gun attack might follow the bomb, partly because early reports suggested casualties had suffered gunshot wounds. The officer deployed 106 armed response officers within an hour, as well as explosive-sensing sniffer dogs from GMP and other local forces.

Quick Guide

Manchester Arena bombing report: the key points

Show

• The Greater Manchester fire and rescue service did not arrive at the scene and therefore played “no meaningful role” in the response to the attack for nearly two hours.

• A “catastrophic failure” by Vodafone seriously hampered the set-up of a casualty bureau to collate information on the missing and injured, causing significant distress to families as they searched for loved ones and overwhelming call handlers at Greater Manchester police.

• Complaints about the media include photographers who took pictures of bereaved relatives through a window as the death of their loved ones was being confirmed, and a reporter who passed biscuit tin up to a hospital ward containing a note offering £2,000 for information about the injured.

• A shortage of stretchers and first aid kits led to casualties being carried out of the Arena on advertising boards and railings.

• Armed police patrolling the building dropped off their own first aid kits as they secured the area.

• Children affected by the attack had to wait eight months for mental health support.

Photograph: Oli Scarff/AFP

Protocol dictated that the force duty officer should withdraw all responders from the arena foyer after initiating Operation Plato. But they didn’t, deciding that to tell these responders to evacuate would have been “unconscionable”. The duty officer was praised for this agonising decision by Burnham, who said: “Individuals on the ground at the arena took brave, common sense decisions which made the response better than it otherwise would have been had they followed protocol.”

In the absence of confirmation of Operation Plato, the fire service stayed away.

Ambulance service

The report concluded it was actually “fortuitous” the North West ambulance service was not informed about Operation Plato – otherwise they may have pulled out their paramedics and instead they stayed and “lives were saved”.

Just three weeks before the attack, Greater Manchester NHS had done a simulation exercise for what would happen in the event of an attack. The freshness of memories in relation to this exercise meant that from the strategic and tactical level, things worked well, Kerslake found.

The first call to the ambulance service came in at 22.32, a minute after the bomb. Subsequent callers reported a variety of descriptions of the event including “speaker exploded” to “multiple gunshots”. An advanced paramedic self-deployed, arriving at the arena 10 minutes later. As he entered he was told by a police officer on the concourse that the incident was a suicide bomber.

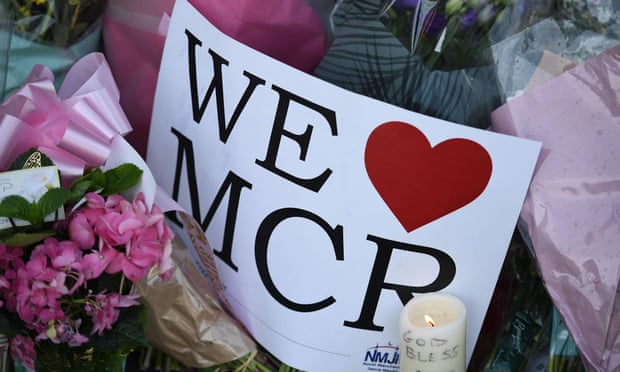

A billboard in Manchester a day after the Manchester Arena attack. Photograph: Kirsty Wigglesworth/AP

Along with a colleague he went into the foyer, where the bomb had detonated, and began to triage patients, despite not knowing if a marauding gunman was on the loose. Some survivors told Kerslake that they felt medical treatment was too slow and that they were left lying on the floor for two hours. But Burnham said criticism that only a small number of paramedics were working in the foyer was “unfair, given that it took police some time to confirm this was not a marauding attack and there were no other devices or attackers in the arena”.

In total, 56 ambulances and seven rapid response vehicles were deployed to the arena, along with six advanced paramedics and three consultant paramedics.

The panel said it was shocked and dismayed by the accounts of the families of their experiences with some of the media. They spoke of being “hounded”, of a “lack of respect”, and of “sneaky” attempts to take photos when families were receiving bad news. “To have experienced such intrusive and overbearing behaviour at a time of such enormous vulnerability seemed to us to be completely and utterly unacceptable,” the authors wrote, adding: “We recognise that this was some, but by no means all of the media and that the media also have a positive and important role to play.”

At the hospitals, families looking for missing loved ones and visiting the injured described having to force their way through scrums of reporters who “wouldn’t take no for an answer”. Some complained that photographers took pictures of them through windows as they were being told their loved ones had died. One hospital worker spoke of a note offering £2,000 for information being included in a tin of biscuits given to the staff.

Several people told of the physical presence of media crews outside their homes. One mentioned the forceful attempt by a reporter to gain access through their front door by ramming a foot in the doorway. The child of one family was given condolences on the doorstep before official notification of the death of her mother. Another family told how their child was stopped by journalists while making their way to school.

Families

Burnham made it clear from the beginning that the experiences of bereaved families, the injured and others directly affected should be at the heart of the process. The review panel heard from family and friends of 11 of the 22 people who died, as well as 200 others affected by the attack.

For those who were bereaved, many found the time it took to receive the news too long and question why they could not have been advised much sooner. Those respondents who were already sure in their own minds had given identifying information to the the police. But most said they appreciated the compassion shown to them at the morgue.

One said of their relative: “All the little bits and pieces, his wallet came back, the respect that’s been shown, because not only were his cards there but there’s a little bag in the wallet that contained every fragment of every card that was chipped and broken. They sent it all back, they haven’t just binned it. They sent every little particle back.

Opinion was split on how £20m donated by members of the public to the We Love Manchester emergency fund had been distributed. “If you ask me about the money, or the way it’s been publicised, it makes me feel ill, but I do have to live, and we do have to pay bills, so we are grateful,” said one.

Another said: “I am self-employed but unable to work due to my injuries. The fund has provided money for rent and to live off but I feel that I am banging my head against a brick wall for support. The fund has offered two lump sums but we were not told when they will arrive or how much we will receive. We do not understand why the fund are so secretive about where the money is going and why the bereaved families were given more money than those living with injuries.”