A Survey of Some of the Best Science Fiction Ever Published (Thanks to Judy-Lynn Del Rey) - Reactor (original) (raw)

The 2010s and the 1970s are similar in many ways: questionable fashion choices1, U.S. presidents under investigation, Canadian prime ministers named Trudeau, the possibility that nuclear tensions might flare up at any moment. The two decades share something else, as well: during both of these decades, it became easier to discover classic SF. In the modern era, we are seeing ebook reprints mining the output of the past. In the 1970s, we had paper reprints, such as the variously titled Ballantine (or Del Rey) Classic Library of Science Fiction.

As with Timescape Books, the Classic series was largely due to the astute market sense of one editor. In this case, the editor was Judy-Lynn del Rey (she may have had an occasional assist from husband Lester2). Under her guidance, Ballantine and later the imprint that bore her name became a signifier of quality; readers like me turned to her books whenever we had the cash3. The Classic Library of Science Fiction helped to firmly establish the Del Rey publishing house.

Each volume collected the best short stories of a well-known SF or fantasy author. I’m discussing a slew of authors in this essay—alphabetized, because trying to list them in chronological order proved unexpectedly complicated.

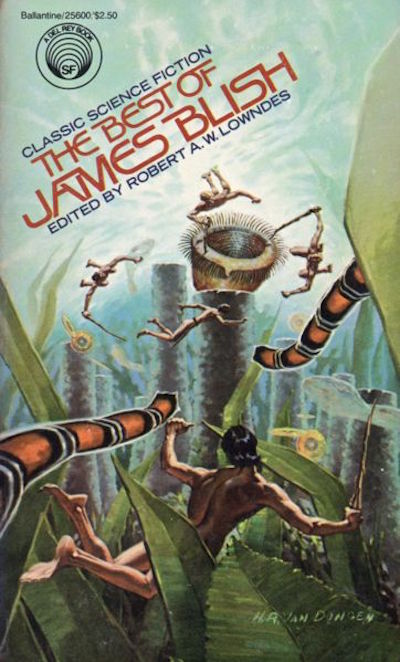

The Best of James Blish

Futurian James Blish (23 May 1921–30 July 1975) may be best known these days as the author of the Cities in Flight series (They Shall Have Stars, A Life for the Stars, Earthman, Come Home, and The Triumph of Time), and his After Such Knowledge series (A Case of Conscience, Doctor Mirabilis, and The Devil’s Day.) Back in the 1970s, many fans knew him as the person doing the Star Trek collections of stories based on the original series. Blish was convinced that SF need not be bound by its pulp origins and published SF criticism under the pen name William Atheling, Jr4.

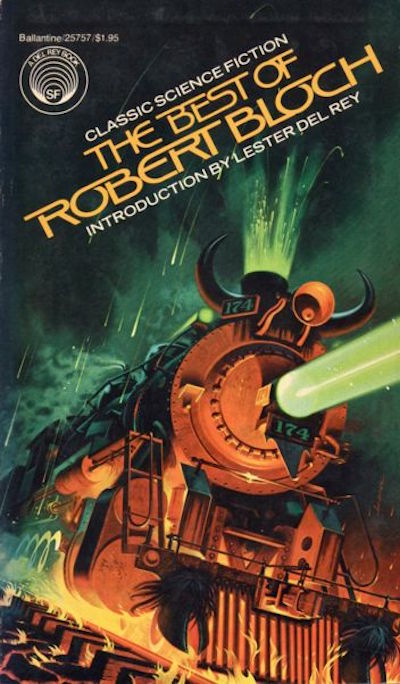

The Best of Robert Bloch

Robert Bloch was a member of the Lovecraft Circle. He published in many genres: mystery, horror, SF, true crime, and more, and was awarded the Hugo, the World Fantasy, the Edgar, and the Stoker. Bloch’s Psycho was the basis for the Hitchcock film of the same name.

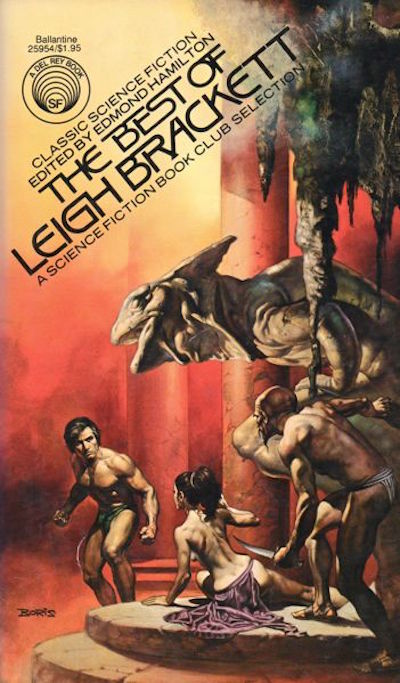

The Best of Leigh Brackett

Pulp-era SF was not known for friendliness to women authors, and Leigh Brackett was one of the few women authors of that era. She is known for her planetary romances, many of which shared a setting. Brackett was also a skilled screenwriter, known for her contributions to The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo, _Hatari!_… oh, and an obscure little film called The Empire Strikes Back.

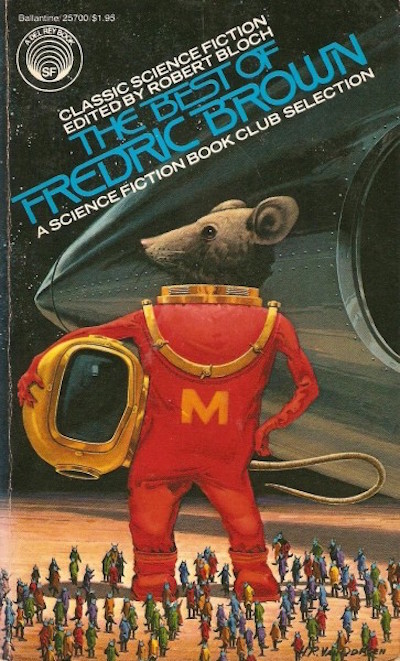

The Best of Fredric Brown

SF and mystery author Fredric Brown was the master of the comic short-short, works so brief that he might spend more on the postage to submit the stories than he could make from the subsequent sale. Among his best-known stories are “Letter to a Phoenix” (which has not aged well), “Arena,” and “Knock,” which begins: “The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door…”

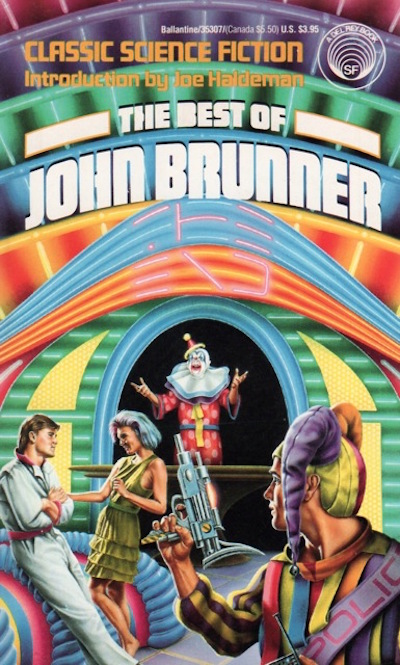

The Best of John Brunner

John Brunner’s fiction covered a spectrum ranging from morose to intensely gloomy. Readers intrigued by this collection who want to enjoy his strengths at novel length should seek out Brunner’s thematically-related SF standalone novels: The Jagged Orbit, The Sheep Look Up, Stand on Zanzibar, and The Shockwave Rider. Each book tackles One Big Issue (racial conflict, pollution, overpopulation, and future shock, respectively).

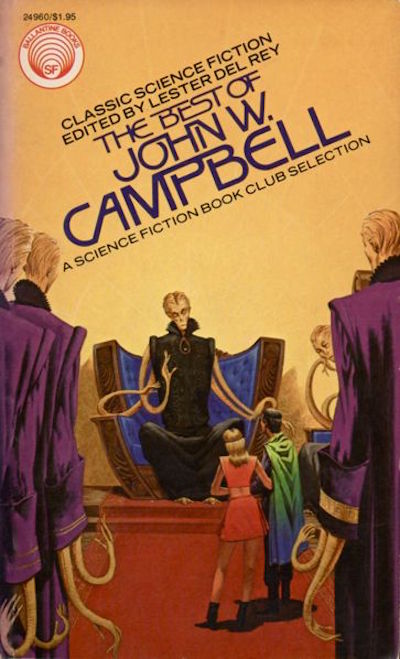

The Best of John W. Campbell

Before he was an influential editor and Patient Zero for several infectious pseudo-sciences, John W. Campbell was a successful writer. His efforts ranged from mood pieces like “Twilight” (not the vampire novel) to star-smashing shoot-em-ups like The Ultimate Weapon. His best-known work is “Who Goes There,” an unsympathetic look at the challenges of assimilation.

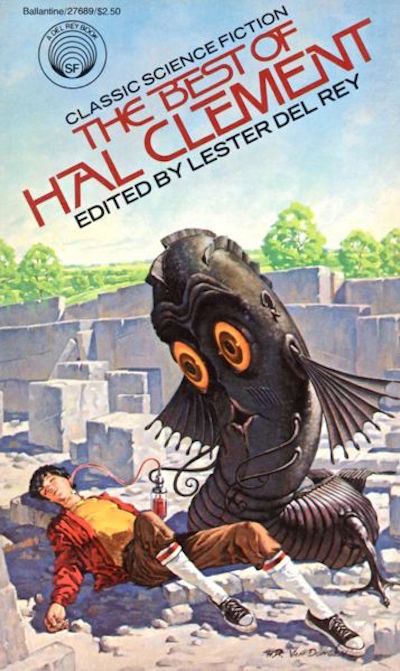

The Best of Hal Clement

Depending on how narrowly one defines hard SF, the amiable Hal Clement may have been the only hard SF author featured in this series. He could wring a story out of a phase diagram. He wrote about non-Earth-like worlds: planets whose gravity would reduce humans to paste, worlds where we would puff into heated vapour.

Current exoplanet research suggests that we are living in a Hal Clement universe.

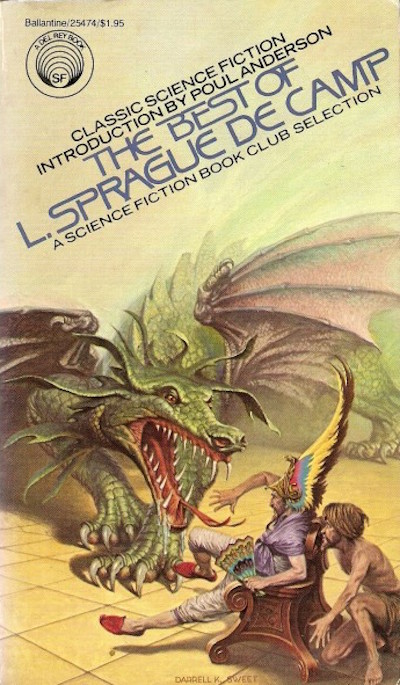

The Best of L. Sprague de Camp

Arguably the dapperest man active in science fiction, L. Sprague de Camp wrote both fiction and non-fiction. He published sword and sorcery, planetary adventure, necrolaborations5, and humorous bar stories (which I found less funny than intended. Though perhaps that was due to the fact that I was reading this book at the time of my father’s funeral.)

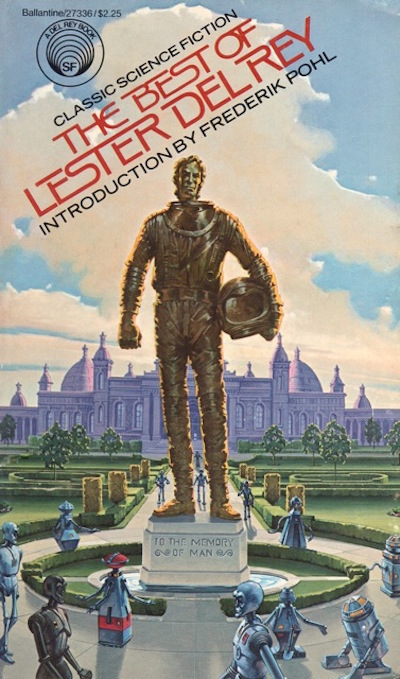

The Best of Lester del Rey

Lester del Rey was both editor and writer. I’m not a fan of his fiction; I’ve always been baffled by the popularity of “Helen O’Loy,” which features a romantic triangle that included a mass-produced robot.

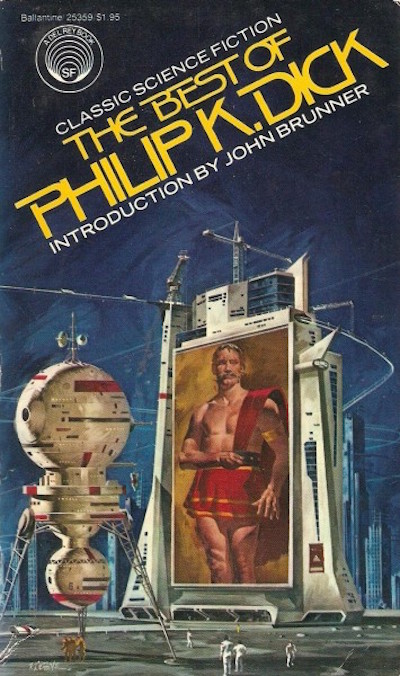

The Best of Philip K. Dick

Philip K. Dick may be best known today as the person whose work has provided material for quite a few movies. He wasn’t big on objective reality as most of the rest of us understand it. He saw depths within depths masked by a thin scrim of illusion. His prose was often energetic, if poorly disciplined.

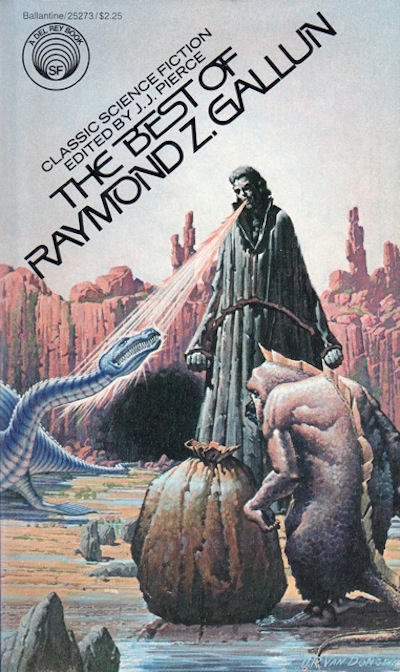

The Best of Raymond Z. Gallun

Raymond Z. Gallun got his start at age eighteen, when his 1929 “Space Dwellers” was published. His fiction always showed its pulp-era roots—but sometimes rose above them, as it did in his story “Old Faithful.” After a hiatus beginning in the 1960s, Gallun resumed writing, and he was an active writer well into the 1980s. Not quite Jack Williamson’s eight-decade-spanning career, but still pretty darn impressive.

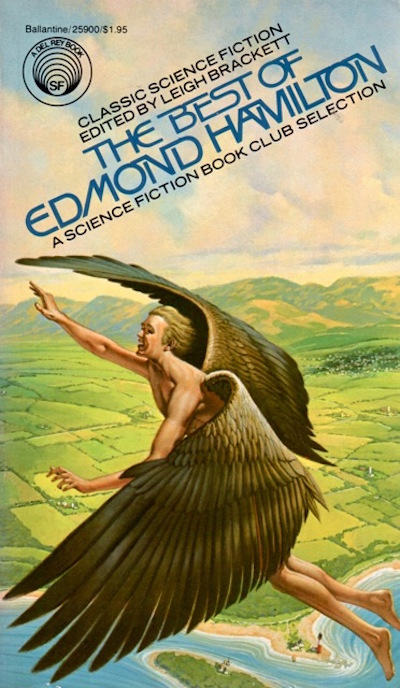

The Best of Edmond Hamilton

Edmond Hamilton specialized in star-smashing adventures. His prose style was workmanlike at best; his science background was nil. However, he wrote impressive spectacles with high body-counts.

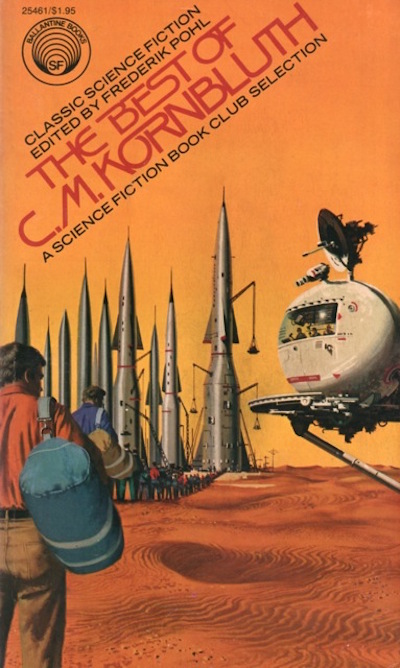

The Best of C. M. Kornbluth

Often found collaborating with Frederik Pohl, C. M. Kornbluth’s bleak, misanthropic fiction allowed magazines like Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction to nudge SF away from Campbell’s vision of a world populated by gung-ho, crew cut-sporting scientists and adventurers. His “The Marching Morons” may be tied with “Harrison Bergeron” for the story most sympathetic to self-pitying nerds. The guy had talent and wrote great stuff. It’s a shame that the long-term effects of his World War Two experiences led to his premature death in 1958.

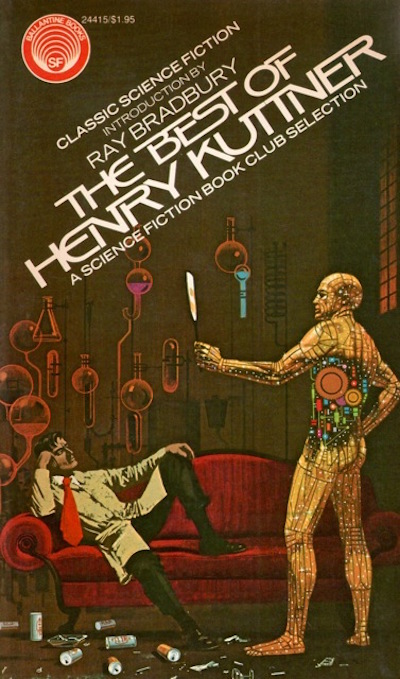

The Best of Henry Kuttner

Henry Kuttner was Mr. C. L. Moore. Thanks to Moore and Kuttner’s habit of poorly documented collaboration, it can be very difficult to establish which of them wrote what. Kuttner’s style was slick, his worldview often cynical, and his fiction often quite funny. He also had an eye for talent: he helped Brackett first see print.

Kuttner died in 1958; given how much smaller the field was in those days, losing two authors of Kuttner and Kornbluth’s stature in just two months must have been a disappointment to fans.

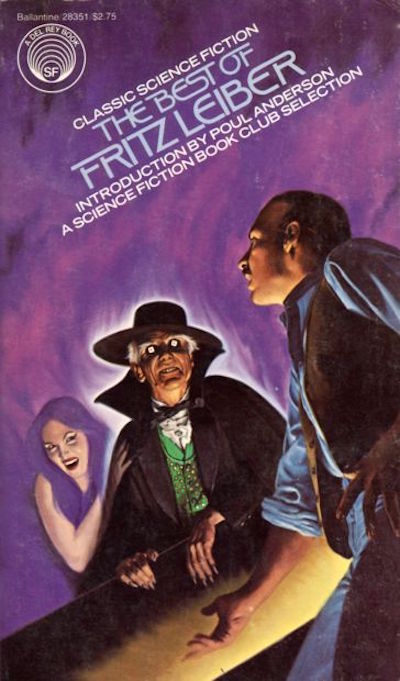

The Best of Fritz Leiber

Leiber started publishing in the pulp era; like so many other pulp writers, he was active in many genres. He wrote several books that have been recognized as genre classics. The Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser books are sword and sorcery classics; The Big Time is a time-travel classic; A Spectre is Haunting Texas is dystopian; Conjure Wife is fantasy. Leiber was also an actor, playwright, poet, and essayist.

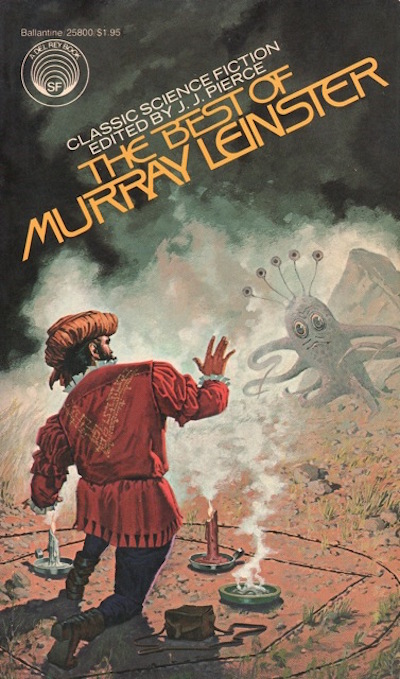

The Best of Murray Leinster

Like Leiber, Murray Leinster (Will Jenkins in real life) wrote in many genres. Over the course of his career, he wrote more than a thousand pieces (novels, stories, essays, plays, etc.). He wrote SF, mystery, romance, Westerns, adventures. He wrote for print, radio, and television.

SF fans may be interested in his story “First Contact,” in which humans and aliens attempt to negotiate peaceful relations. Fans of alternate history may be interested to know that the Sidewise Award for Alternate History takes its name from Leinster’s “Sidewise in Time.”

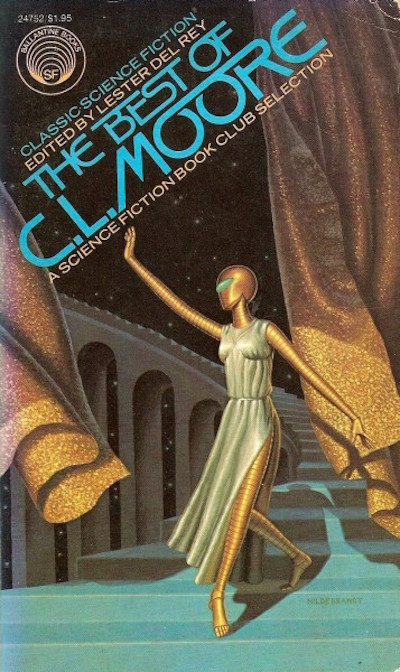

The Best of C. L. Moore

Many of the women working in early SF have been left out of histories. C. L. Moore is one of the exceptions. While her later work is inextricably entangled with that of husband (Henry Kuttner), she was already a star when they married. (In fact, it was the quality of her writing that first interested Kuttner.)

What may interest modern readers: the Northwest Smith stories, which feature a handsome doofus who never met a pretty woman whose death he could not inadvertently instigate. Also her fantasy stories starring warrior Jirel of Joiry, who once fed a vexatious suitor to a demon. One series (Northwest Smith) is SF and the other (Jirel) is fantasy, but they did take place in the same setting, if many centuries apart6. SF or F? Often a matter of interpretation.

Moore would have been the second woman named SFWA Grand Master, had her second husband not intervened. She had developed Alzheimer’s in her old age; he was afraid that she would not be able to cope with the ceremony.

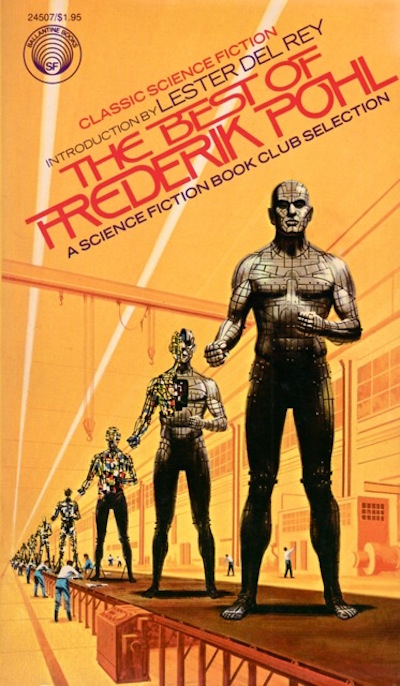

The Best of Frederik Pohl

Frederik Pohl had a seventy-five year career during which he was active in almost every possible niche in SFdom as a writer, editor, and fan. (I don’t think he was an artist but I may have missed something.) He won a string of Hugos for his work as magazine editor. While working for Bantam books, he championed classic works such as Delany’s Dhalgren and Russ’s The Female Man. As a writer, he co-wrote classics like The Space Merchants; he also won Hugos for his solo works. He was long active as a fan; he barely missed being there for the very first WorldCon due to some particularly bare-knuckle fannish politics. He was widely known, respected, and liked. He was celebrated in Elizabeth Anne Hull’s tribute anthology, Gateways.

It was an honour to be utterly crushed by him for a Best Fan Hugo in 2010. After all, I was the one who pointed out that Pohl was eligible in the first place.

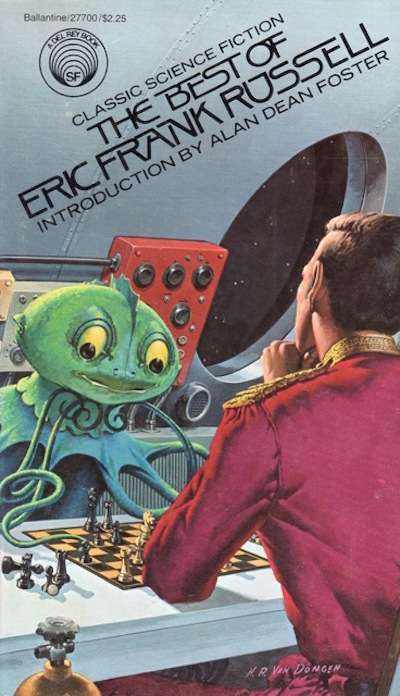

The Best of Eric Frank Russell

Eric Frank Russell may have been seen as a comic writer, but his satires could have dark overtones. His novels often suggested that there was far more to the universe than we knew, and that additional knowledge would not bring comfort. Despite this, his work was occasionally warm and life-affirming.

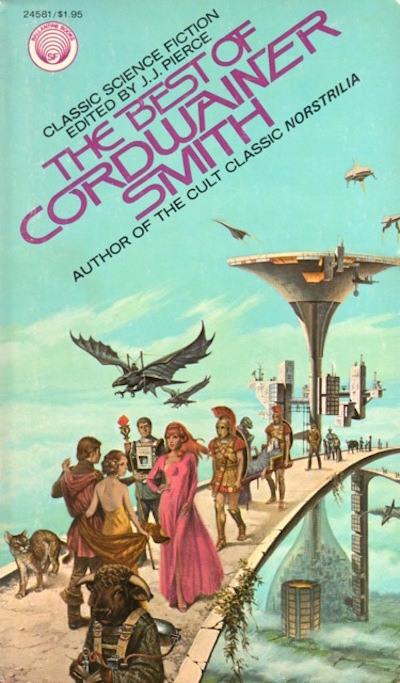

The Best of Cordwainer Smith

Cordwainer Smith was the pen name of Paul Linebarger: soldier, expert in psychological warfare, East Asian scholar, and godson of Sun Yat-sen. Smith drew on his Asian expertise when writing SF. His works were far from typical of the SF being published in North America at the time.

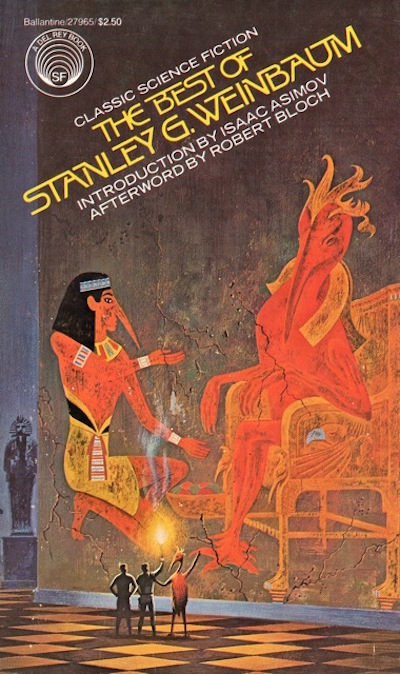

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum

Isaac Asimov compared Stanley G. Weinbaum to a supernova. This was apt both as to brightness (stellar career) and brevity; Weinbaum published for less than two years before he died of cancer. Many of his SF works share the same planetary SF setting, which included a tide-locked Venus and the curiously habitable moons of Jupiter.

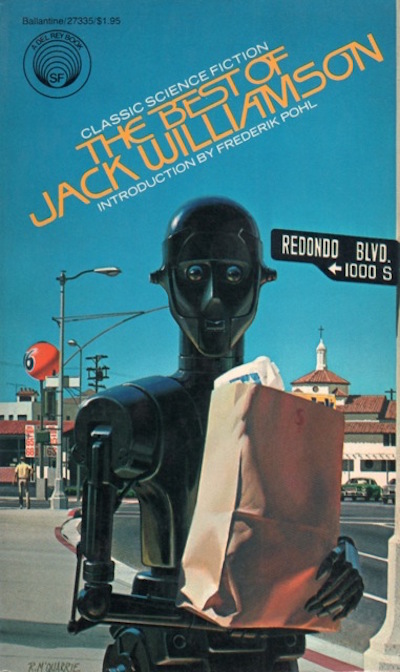

The Best of Jack Williamson

Jack Williamson’s career spanned an astonishing eight decades, from the 1920s to the 2000s, from the pulps to modern times. He wrote classic fantasies like Darker Than You Think, epic space operas like The Legion of Space, and interplanetary thrillers like SeeTee Shock. Readers might enjoy his story “With Folded Hands, in which humans are gifted with all the solicitous robotic caretaking they could desire…and perhaps more.

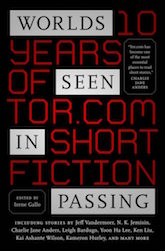

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing: Ten Years of Tor.com Short Fiction

1: OK, only because “questionable fashion choices” is a cross-generational universal. But still, what were we thinking? Shirts made of solidified napalm and tragic sideburns were just the beginning of the horror.

2: Not that Lester was a mere hunky sidekick. He edited Ballantine/Del Rey’s fantasy line and like his wife, had a keen eye for commercial potential. It just goes to show that some SF hubbies are more than just sultry eye candy: all you male SF writers/editors coasting on your looks, try harder!

3: And we had to be judicious in our spending back then. Post-oil-crisis inflation meant that paperbacks could cost as much as a dollar ninety-five! I remember clearly the day I purchased a book for exactly ten times the amount I had spent on my first mass market paperback. I also remember the glazed look on the face of the bookstore clerk as I explained at length the interesting fact that years before he was born, books cost as little as seventy five-cents.

4: I will put this down here and maybe nobody will notice it. Unlike many authors who are called fascists simply because they are political troglodytes, Blish really was a self-described “paper fascist.” Judging by the intro for his fascist utopia A Torrent of Faces, he didn’t think much of the prior art in the fascism field.

5: My coinage for collaboration with a dead author, sans benefit of medium or Ouija board.

6: Thanks to time travel, Northwest did cross paths with Jirel, whose reaction to his rugged, useless charms can be best summed up as a derisive snort.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.