'The Wild Tchoupitoulas': The Story Of A New Orleans Classic (original) (raw)

Quite simply, one of the most wondrous representations of New Orleans ever put to tape.

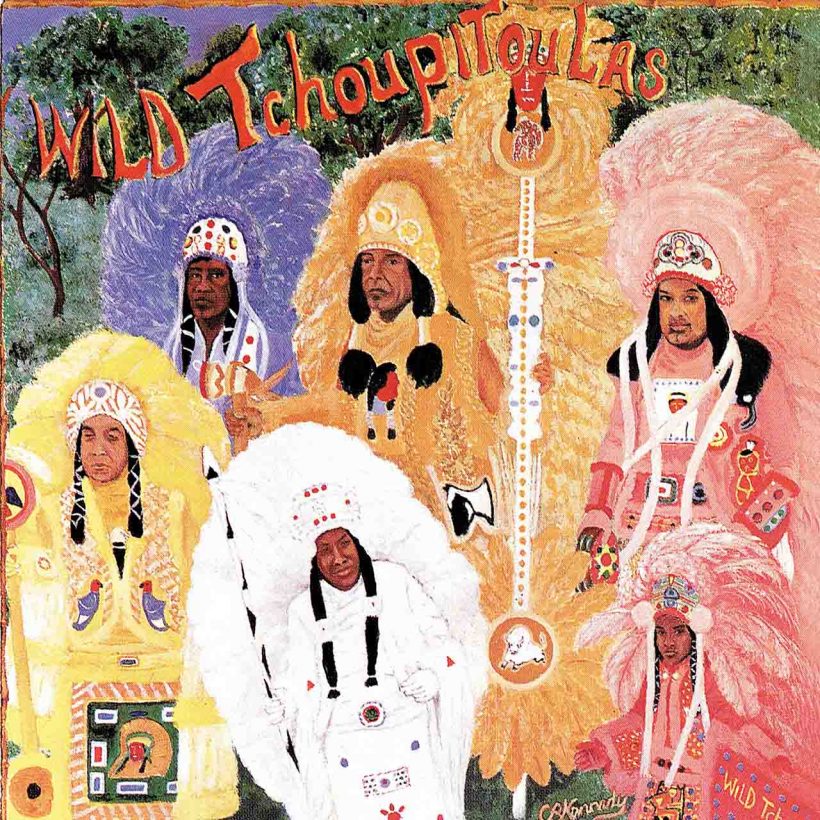

Cover: Courtesy of Universal Music

Though renowned for the splendor of their meticulously hand-sewn headdresses and suits, **New Orleans**’ Mardi Gras Indian tribes fundamentally represent solidarity, community, and resolve. Their origins may be traced at least as far back as the 1800s, when Native Americans – under punitive threat by federal authorities – sheltered and abetted enslaved African descendants seeking freedom. When pre-desegregation African-Americans were banned from (white) Mardi Gras Krewes, they paraded as Mardi Gras Indian tribes, commemorating their bond with Indigenous peoples. As New Orleans’ population evolved, they began to absorb Caribbean influences within their ritual costumes, dance, and music.

The latter’s Creole patois call-and-response chants and persuasive rhythms represent a true hybrid of cultures – like so many things distinctively New Orleans. By the mid-1970s it was also due for proper documentation. Chief Bo Dollis’ Wild Magnolias had already released well-regarded recordings fusing Mardi Gras Indian vocals with band backing. But George Landry, AKA Big Chief Jolly, founder of the Wild Tchoupitoulas, was positioned to do something even more special. Landry’s nephews just happened to be the city’s first siblings of soul and funk, Art, Charles, Aaron, and Cyril Neville. Art’s band, The Meters, were the most rhythmically revolutionary funk outfit this side of **James Brown**’s original JBs, and had long served as studio musicians for revered producer Allen Toussaint.

Listen to The Wild Tchoupitoulas self-titled album now.

That they all converge on the Wild Tchoupitoulas’ self-titled 1976 album alone makes it a milestone. That it also organically connects the dots between the disparate strains of the city’s musical heritages makes it one of the most wondrous representations of New Orleans ever recorded. As chief, Landry largely assumes front and center. His baritone – suitably raspy, considering his lyrical boasts of Mardi Gras Day fire water consumption – leads his other tribesmen and the Nevilles through festive rallying cries touting the superiority of the Tchoupitoulas’ suits, style, and panache in face-offs against rival tribes (the exuberant “Indians Here Dey Come” and “Big Chief Got a Golden Crown”; the ceremonial majesty of “Indian Red”). A lilting reggae groove with a calypso-inspired melody, “Meet De Boys On De Battlefront,” in particular, functions as both a chronicle of Carnival pageantry and a toast to the fierceness, in all respects, of the tribe and its ancestors: “I’m an Indian ruler from the 13th ward/Blood shief-a-oona I won’t be barred/I walked through fire and I swam through mud/Snatched the feathers from an eagle, drank panther blood.”

Meet De Boys On The Battlefront

Click to load video

Providing the perfect counterbalance are the tracks more prominently featuring the Nevilles. A cover of The Meters’ “Hey Pocky Way” beautifully blends the brothers’ group harmonizing (Aaron’s unmistakable high-pitched timbre cutting through) with drummer Ziggy Modeliste’s signature second-line rhythmic riffing. “Brother John,” penned and sung by Cyril, exalts John “Scarface” Williams – Apache Hunters Indian and former singer with bandleader Huey Smith – who was killed breaking up a knife fight in 1972. Cyril would later describe the tribute to author David Ritz as an expression of “that weird mixture of violence and beauty that was part of our R&B street life.” He might very well have also been describing an album as unique as anything in the NOLA musical canon, whose joyous realization was generations in the making.