Albert King’s Flying Vs | Vintage Guitar® magazine (original) (raw)

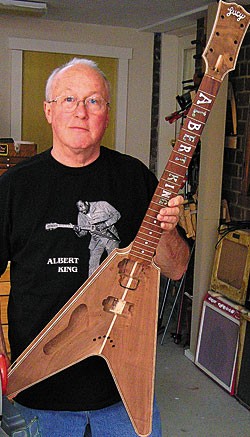

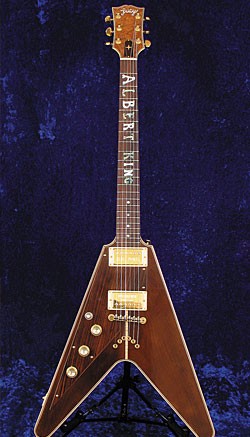

The ’59 Gibson Flying V made famous by Albert King (left), along with the “Lucy” guitar built by Dan Erlewine in the early 1970s, and the mid-’60s Flying V King played extensively after his ’59 V was lost. Photos by Rick Gould.

In a quiet, wooded canyon blissfully removed from the hustle and bustle of nearby Hollywood and the roar of Pacific Coast Highway, sits the very private retreat and Shangri-La of Steven Seagal, well-known movie actor, martial arts master, and dedicated blues-guitarist/fanatic. There, he recharges his creative and spiritual batteries between projects and career demands, surrounding himself with Asian and Eastern artifacts, in a tranquil setting that reflects his fusion of the Californian and Oriental.

There he also hosts cognoscenti on the occasional pilgrimage to what has grown into a veritable museum of blues guitar and arguably the finest collection of such instruments in the world. Alongside ornate inlaid Persian furniture, lustrous silk tapestries and serene wall hangings from the Far East are rows of vintage Marshall stacks and cases housing treasures of the Kings. No, not King Nebuchadnezzar nor kings of the Shang and Yin dynasties, these are guitar cases containing iconic instruments of the American blues Kings – Freddie, B.B., and Albert. Such is the eclectic and inclusive mosaic of Seagal’s multicultural world.

Seagal has attained admiration and notoriety among blues devotees for his custodianship of these classic American axes, previously owned by such legends as the Kings, Bo Diddley, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Buddy Guy, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and Jimi Hendrix. Unlike many of his self-absorbed film cohorts, he has put his money where his mouth is, taking the time, resources, and effort to rescue and restore countless gently weeping historic instruments.

On a recent visit by VG, Seagal, along with ZZ Top co-founder/guitarist and fellow blues-music historian/aficionado Billy F Gibbons, paid homage to three Flying Vs once played extensively by the great blues master Albert King. The two took turns strumming, inspecting, and discussing the guitars, which are now part of Seagal’s amazing collection.

Billy F Gibbons: These guitars are so important; they represent what came out of Albert with his hands. Look at the beauty of these keys; they have not deteriorated. I think anyone lucky enough to play the Gibson Flying V from the late 1950s would concur that it is not only one of the most exotic instruments, but came from the zenith of Gibson’s manufacturing expertise.

Steven Seagal: I hope seeing them will bring some joy to blues aficionados and people who revere these guitars like we do. These guitars tell a story. When you pick them up, they almost play themselves. They have so much spirit in them; the Gibson korina and the Erlewine particularly have a lot of mojo.

Check out the body, where Albert made an impression into the top with the pressure of his hand.

**BFG: My God!

SS: Yes, as you can see, Albert almost wore a hole in solid wood from playing it so much.

BFG: Out of curiosity, where did this one surface?

SS: There’s a rumor that Albert lost it in a craps game in the late ’60s. Whether at the game itself or as a debt he paid later, this guitar went for $2,500. The person who bought it was supposed to hang on to it – he promised never to sell it. So it disappeared for more than 20 years, hidden in Memphis. But I knew who had it, and found him. I’ve kept it quiet for many years; not many have seen it.

BFG: Languishing all these years in Memphis…

SS: Yeah. I think it is the most important blues guitar in the world, period, and it’s the best-sounding V around – a voice from another planet. It has the most amazing tone and it has all of Albert’s energy in it. It’s one of my greatest treasures. I have Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Firebird with the personally carved names of Stevie, Albert King, and Muddy Waters, but this one is much more important.

I’ve played it through a late-’60s plexi 100-watt with a 30-watt slant cab in bigger shows and through a 100-watt Fender tweed Twin, which is what I’m using now. When you take two or four of those Twins and play this through them… it screams, but it has beautiful harmonics and unbelievable tone.

What do you think Albert played it through when he recorded?

SS: He used the crappiest amps, didn’t he? Solidstate Acoustic amps… and later, a Roland Jazz Chorus – another solidstate amp.

BFG: I couldn’t say what Albert used in the studio. Live, he used this tall Acoustic amp when I saw him, and later added a Maestro chorus pedal to it. I remember he had a proper flight case for his guitar and he would set the case in front of the amp on stage. When he wanted it louder he moved the case, like it was a baffle.

SS: I don’t know about what he used in the studio, either. But I do know with him it’s not about the amp – whether it was solidstate or tubes – it’s about the player; it’s the way he used his fingers and the way he squeezed the tone out of his guitars.

There’s a rumor Albert recorded with a small tweed amp, like Steve Cropper’s Fender Harvard. Any thoughts?

BFG: Could be, I’ve got Steve’s Harvard amp and his old Tele. Cropper scratched his address into that guitar (laughs)!

One thing that stands out in my mind is not only was Albert a great soloist as a blues guitarist – he certainly did the statement – but his singing was so appealing.

SS: Friendly, warm.

BFG: The high point was when he got together with the Memphis Horns and… was it Booker T & the MGs in the rhythm section?

SS: Yeah, all Memphis cats.

Steve Cropper…

SS: …Steve Cropper, David Porter, “Duck” Dunn, all of them…

BFG: “Born Under a Bad Sign” from 1967 – the sound was amazing. I was at Kiva, I think, when they were recording. We were talking during a break and I made a remark about how rich the Stax sound was. Over the years, many people have wondered about that sound because the records had such a cohesive quality. I asked them, “Was there some thought that went into designing that sound? Was it a planned thing?” Albert laughed and said, “Tell him, Steve.” Cropper asked if I’d ever been to the Stax studio in South Memphis. I told him, “Not if I could help it.” It was in an old movie theatre in the worst part of town – dangerous country, as bad it gets. It turns out they had so many break-ins that they finally bolted the amps to the concrete floor. They also bolted down the mic stands, the drums, anything else that could be stolen. As a result, nothing was ever moved and the sound didn’t change. They wouldn’t even let the cleaning people move anything around.

Here’s Albert’s 1966 Gibson Flying V.

BFG: Another example of a fine-playing instrument; most Gibson guitars from this year are still excellent. They seem to have maintained a standard of quality longer down the line, compared to Fenders after the CBS takeover in 1965.

SS: I think Gibson gave this to him. He’d already lost his original korina V and he replaced her with this ’66. Albert wrote and recorded a bunch of famous songs – like “Born Under a Bad Sign” – with it in the late-’60s Stax period.

Do you think Albert was drawn to the Flying V for a reason?

SS: He made it famous, I’ll tell you that.

But why not the conventional blues guitar route – an archtop like T-Bone, a semi-hollow like B.B., or a Strat?

SS: He was an entertainer, man! There was the visual side.

BFG: It was about style, you know? The V was not a popular instrument at the time, but for so many players it’s something to stand behind because it was such an odd…

… Striking?

BFG: …Yeah, a striking instrument. Mine is a ’58; was Albert’s earlier?

SS: Its [serial number is 1959] but some of the parts are from the early ’60s. I believe Gibson gave that guitar to Albert around 1962.

What guitar was Albert playing before the V? Anyone know?

BFG: I don’t think he did play another. I think he went straight from the drum set to the V – just started twanging. The V might have stimulated his interested, got him curious. He probably said, “I’m going to stand behind this thing.” I don’t know a lot about his early work; I have some old singles like “Let’s Have a Natural Ball.” But he has been well-documented and only after he’s dead and gone does everyone make much of what he did.

SS: Speaking of dead and gone, toward the end, Albert wasn’t feeling well. The last time I saw him he didn’t look good at all; his eyes were swollen and his face was puffy. He had a heart attack and asked a girl to drive him to the hospital. So she drove him. Well, you know how Albert had all those nice rings and stuff. This girl was so concerned about his gold and jewelry that she drove him to the parking lot, stole his jewelry, and left him to die in the car. All she had to do was drive to the front door, to the emergency room, and he’d probably be here with us now.

Talk about the Dan Erlewine-made V…

SS: I’ve had it about eight years; I bought all three roughly within the same period of time. The Dan Erlewine V is made of black walnut, but it has [a maple strip down the middle]; it’s called Lucy. I think he called the earlier one “Lucy Blue.” Albert played shows all over the world with this guitar; he did interviews with it and about it. He claimed it was the guitar of his life, but I think that’s because the korina was gone.

There’s a spooky story attached to this guitar. I’ll let Peter (Seagal’s friend and guitar repairman) tell it. He worked on the guitar for a while.

Peter Skaltsis: This guitar was at my house for quite some time while I was working on it. I was downstairs in my shop when my younger son – he was seven at the time – came in crying; he was really scared. He said, “There’s a black man sitting on the sofa – a big black man.” I ran upstairs thinking someone had broken in, but when I got there no one was in the room. I still get goose bumps talking about this. I called Steven and he said…

SS: Show the boy a picture of Albert King and ask him if that was who he saw. He said, “Yes, that’s who I saw… God’s honest truth.”

BFG: Wow… When you’re seven you wouldn’t make up something like that. I don’t know, man… these instruments are imbued with the power of the player.

…Especially a power as strong as Albert’s.

BFG: He was pounding it into the guitar.

SS: Albert loved this guitar.

BFG: He did; he played it religiously. This guitar is a little better known and is associated immediately with Albert.

Because of his later work with it?

SS: Yeah, he just played it everywhere… to the end of his life. That’s the last guitar he played. I think the one you gave him, Billy, wasn’t played very much.

BFG: Yeah, I don’t think so. I’ve only seen one or two photos of him with that V.

Albert wasn’t one to have spare guitars; he played one guitar the whole night. With all that string bending did you ever see him break a string?

SS: I never did.

BFG: No, I didn’t either. And he did those two-string bends, man… (sings an imitation of Albert’s bends).

That technique was heavily imitated – especially by Stevie Ray Vaughan.

SS: Stevie copied a lot of his stuff.

BFG: Albert was upside down on the guitar (strung like a right-handed guitar, played left-handed) and it’s not easy to do that and be technically correct.

And he was in an alternate tuning…

BFG: Because of that unorthodox style, a lot of stuff came out of his hands that is otherwise not possible; Jimi Hendrix, same thing.

One show, in 1972, I think, had Albert and B.B. I was asked to stand in for the guitarist in the opening band, which I knew quite well. It was a chance to play with Albert and B.B. I was warming up backstage and Albert came up to me. I think I had a Fender Telecaster at the time. I had it strung with the heaviest strings, thinking a bluesman played the heaviest strings you could find. Albert asked to play my guitar. He had it upside-down and played a little bit. Then he asked, “Why are you using these strings?” I told him because I wanted to have that bluesy sound. He said, “Why are you working so hard? Get something light!” (laughs)

What the old blues guys did before light strings were available was buy a set of Gibson Mono-Steel or Black Diamond strings. They’d get rid of the sixth string, then move every string over one and use a banjo string on top.

At the end of his career Albert went pretty quickly; he was active until just a short time before he died.

SS: That’s right. He just started feeling bad and said, “I’m thinking about retiring.” Then he went.

BFG: He had a going-away party one Friday night in West Memphis at a little funky joint. He said, “Ladies and gentlemen, this is it – a going-away party for me, Albert King; I’m gonna pull it to the curb.” It was a warm moment. We were talking with him during a break and he told us, “Don’t miss tomorrow night, I’m gonna make a comeback.” Okay (laughs)!

SS: That sounds like Albert.

BFG: He was loved by so many. There’s a little barbeque joint, the Rendezvous, in an alley off Union Street near the Peabody in Memphis; it’s run by Nick Vergos and his dad. The police and Albert King always ate there at no charge. But brother, he could pile on the ribs.

SS: He was a rib-eating mother…

BFG: You didn’t want to get in the way of his knife and fork. He didn’t like paparazzi, especially when he was eating. There was a photographer who traveled the nightclub circuit; made his living with Polaroid shots – souvenirs – selling them for five bucks. You’d find him on Beale Street; he’d pop up anywhere, everywhere. Anyway, he tried to take a shot of Albert one time without asking and Albert did not want to be bothered…

SS: I know, I saw Albert get in someone’s face about that. And he always carried a pistol; you might not have seen it but I’ve seen him take it out, a little black one that he wore on his right hip.

It seems everyone who knew him had a memorable Albert King story to share.

BFG: On the way over it occurred to me… just a fond recollection of Albert: My girlfriend, Christine, organized a surprise birthday party for me… I was living in Memphis at the time. And the big surprise was when I came into the room, she had gathered our close friends and whatnot, and there was Albert sitting at the piano. She had rented this big room at the Peabody, and we just had a grand time.

You know, with everyone who has an Albert story, you can bet it’s a good one and generally uplifting, although they may have a different take on it.

SS: We all loved Albert, but we knew him to be a fierce guy, a big guy with a bad temper; he could be very cantankerous. And he was also very charming; he had a lot of personality and a great sense of humor.

BFG:Talk about stories, until recently I didn’t realize that Albert King started as a drummer.

SS: That’s right.

BFG: What band was he in?

SS: I don’t know, but when I was playing with Elmore James’ cousin, Homesick James, he was telling me, “Yeah, Albert King used to play drums for me.”

He also played drums with Jimmy Reed and John Brim.

BFG: Oh, yeah. And I think Albert either went by the name of T-99 or there was a nightclub called The T-99. He had, back in the ’50s, a brand new Buick. What was the fancy car of the line, the Buick Special, the Delta 88 or something? Albert had these air horns mounted to the front fender – giant, three-foot long trumpet air horns from a truck. Years later, our buddy who owned the Peabody – Gary Bells…

SS: …Right, Jack and Gary Bells.

BFG: …Gary bought the Bar Kays’ recording studio, revamped it and renamed it Kiva recording services. And as that was coming together, he became Albert’s manager.

SS: …did for a while, yeah.

BFG: I remember when the studio was finally completed, Gary asked me to come over and check it out. And it was very impressive. They had taken what had crumbled into a ramshackle structure and really put it together nicely. Albert was sitting in the office and just prior to this, someone had shown me a picture of his Buick with the big trumpet air horns on it. I brought it up to him and he laughed. Well, two or three days went by and we were walking down Beale Street. About a block ahead of us was Albert, who stepped out of a building; he saw us coming up and motioned to us to come over. He said, “C’mon, I want to show you something.” He had just bought a brand new Chevy Suburban and it was parked in the back of the building. So we walked through and came out back. He said, “Yeah, I got me a new car. Beautiful, big, brand new Suburban.” And he had those same truck air horns on the front. Albert said, “I remember you telling me, and that reminded me.” He said, “I knew there was something missing!” (laughs)

Another friend of ours, Tony, his parents owned the distribution agency for Taylor frozen-drink machines; daiquiris, margaritas, frozen ice cream, if it was cold and slushy, this was the machine. Anyway, they had the distribution through Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and later New Orleans, which was just amazing… can you sell a frozen drink in New Orleans?

SS: Daiquiris on every corner!

BFG: The Taylor company developed a frozen-drink machine and was forcing all their distributors to buy 50 of these machines. Well, it turns out they had a design flaw and the product kept freezing; you couldn’t get anything out of them. Tony found a guy – an old black gentleman – who had a way to fix the machines, bought all of them from his dad – who thought he was crazy – and managed to secure a storefront on Beale Street. That was right across from the old Daisy Theater – great location in the sweet part of the East Side just when it was first getting popular. Anyway, we were visiting him on the way to Vegas, walking up to the daiquiri shop when we saw Albert – he had just come out of Tony’s shop and was standing on the corner. He had a big cone of soft ice cream, wearing denim bib overalls with a black-and-white checkered sport coat, and brown patent leather shoes in like size 100 (laughs)! He was eating ice cream and smoking a pipe at the same time.

You know, there’s Freddie King, B.B. King and Albert King, with them you couldn’t go wrong. All of them are stunning players. Being a fan of the way Albert played, it was something to find he started on drums. He was left-handed, so everything was backward, but it didn’t stop him and he developed a style that was so personality perfect.

SS: The way he bent notes is something nobody else has done; he did it better than anybody.

Anyone who bends those wide intervals is alluding to Albert in one form or another.

SS: Like bending those huge steps between notes.

BFG: And he was so entertaining. When you went to see him play, you’d always have a good time because he liked to have a good time. Albert turned every small juke joint appearance into an event.

Steven Seagal

Seagal’s New Blues

Steven Seagal has never been one to rest on his laurels. Deluged with demands to make action movies and personal appearances, Seagal invariably has a music project in the works.

His latest recording venture finds him reappraising the classic blues he holds dear to his heart. For those not familiar with his playing or previous releases, it’s well worth investigating Seagal’s spin on the form. Though in initial stages of production, the concept behind his current project is compelling, portending a record that could resonate with even the most implacable listeners.

Is there a theme to your new project?

It’s influenced by hill-country music. There was a time in the history of the blues, even in the Delta, when they had what was called “hill-country music.” It was black people who only knew the blues mingling with whites that only knew bluegrass. They listened to and were influenced by each other. I don’t know how much was recorded, but as a child growing up in Louisiana, I got to hear a lot of it; it was just something people played. I think R.L. Burnside was doing some.

In terms of instrumentation, I’m bringing in some real bad boys, as well as legends out of Nashville. I’m using fiddle, mandolin, and banjo mixed with traditional blues instruments. I’ve had the idea for a long time, marrying hill-country bluegrass with Delta and Louisiana blues; it’s very moving with great grooves, feel, and soul. It represents an overlooked piece of history.

Is the music electric-based?

Yes. We start as electric blues, then add the flavor of mountain instruments; it’s kind of a fusion of country and old blues with electric sounds.

What stage is the music in currently?

Right now I just have a trio. I wrote all the songs and laid the guitar down, as well as bass and drums. I recorded those in Memphis. I lived there and worked at Papa Mitchell’s studio; he’s a dear friend and helped me capture the real vibe. Then I came to L.A., where I brought in Vinnie Colaiuta and Abe Laboriel to do the drums and the bass. They played over my parts. And I brought David Lindley in to play some slide guitar. I had very specific ideas about what I wanted, and they gave it to me. And then I added some Nashville cats playing fiddle, mandolin, and banjo. The music is in its basic form – rough mixes of rhythm tracks without vocals and without solos. I plan to play a lot of solos, have some surprise guests, and get some church girls from Memphis to put a gospel feel in there.

I hope to have the album finished and out in time to be submitted to the Grammys in the Blues category. Like my last album, which had Robert Lockwood Jr., Koko Taylor, members of the Muddy Waters band, and others – these were legends and this was the last thing they played on – I’m doing this for them and the music, not myself.

What guitars are you playing on the tracks so far?

So far, I’ve used a Fender Broadcaster, an early-’50s Strat, and a Gibson Firebird, all vintage. – Wolf Marshall

Dan Erlewine in his shop with an “under construction” Lucy.

A Lucy guitar built by Erlewine in 2006.

Dan E. And Lucy

building a guitar fit for a king

In the fall of 1970, Albert King played the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in Michigan. Among the thousands of spectators at the event was Dan Erlewine, an Ann Arbor “townie,” guitar repairman, aspiring blues guitarist, and for that weekend, a stagehand.

“When Albert played, I was supposed to be his backup guitarist,” Erlewine recalled. “But I chickened out, big-time, and my friend, Pat O’Daugherty, took my place. Those familiar with King know he was at the height of his power and playing at that time, and it truly was like being in the presence of a king!”

The next fall, King returned to Ann Arbor to play the Canterbury Coffeehouse. There, Erlewine approached him about building a true left-handed V.

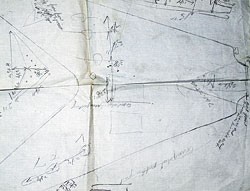

“I told him I had 125-year-old black walnut I bought in 1965,” he said. “In true hippie – and probably inappropriate – fashion, I described the wood as being ‘the same color as your skin.’ Of course, I meant that as a compliment, which Albert must have realized, because he came to my shop the next day to have me measure the original Lucy – his ’59 Gibson Flying V.”

Looking at it now, Erlewine’s “blueprint” looks like little more than a tracing on graph paper with scribbled notes and measurements. But it was the seed that eventually spawned one of King’s most beloved guitars. We talked with him about the guitar and the experience.

What sort of notes did you make on the guitar?

Stuff like “flat-wound G string,” “Black-Diamond ‘Silver’ strings,” and “D, G, D, G, B, E tuning.” Unbeknownst to me until that time, Albert didn’t use standard tuning. He tuned a whole step low, plus he tuned the low E and A strings another whole step, producing C, F, C, F, A, D. However, either Albert was not tuned a whole step low that day or I was confused, because I notated his tuning as D, G, D, G, B, E which reflects a step higher.

Did Albert ask for any specific custom touches?

Oh, yes. He wanted his name inlaid in the fretboard, and wanted “Lucy” inlaid on the peghead. Sorting through my stash of pearl, he selected white pearl and abalone – abalone for position markers at the third, fifth, seventh, ninth, and 12th frets, so he could see them under stage lights.

Joan Erlewine, Ellen Gagliano, Albert King (with Lucy), Meredith Erlewine, and Dan Erlewine in 1989.

Erlewine’s “blueprint” tracing and notes on Albert King’s ’59 V.

How long did the build take?

I delivered Lucy the following spring, in May, 1972. Other than on record album covers, I never saw the guitar (or Albert) again until 1989, when he sent her to me in Athens, Ohio – via Greyhound bus – for fret work and fine-tuning. When I picked her up at the bus station, she was in her case, but not packed in a box; the case was simply tied inside a jute onion bag that you could see right through – tags, venue-stickers, and even his name and address visible through the large mesh for any guitar-knowing thief to see.

What sort of condition was it in?

Well, it had been worked on at least twice. My cousin, Mark Erlewine, who lives in Texas, had re-fretted it in the late ’70s or very early ’80s. And in the mid/late ’80s, Albert’s equipment-trailer was tossed into a creek by a tornado and Lucy spent 24 hours underwater, where a lot of her joints came unglued. She was respectfully repaired by Rick Hancock in Memphis.

Anyway, I turned Lucy around that weekend and got her right back on the bus. About a year later, Albert played a blues club in Columbus, and I went to hear him with my wife, Joan, daughter, Meredith, and her girlfriend, Ellen. Albert was playing Lucy, and at show’s end he asked us to stand and take a bow, then invited us backstage.

And then you went another long stretch without seeing it, right?

Yes. In 2004 – 33 years after I built it – I was asked to make a replica for Teddy, a guitarist from Norway. He was pleasantly surprised to learn that I still had the black walnut, having hauled it from town to town, home to home, and shop to shop since 1965. I had built a few guitars from it, all at the same time as Albert’s, including a Les Paul-style for a friend, and two Strat copies – one for Jerry Garcia and one for Otis Rush. But by then I was so involved with repairing guitars that I didn’t have time to build, except for an occasional custom order. But I never built another V. And I didn’t use the walnut again because I planned on building furniture with it. Before I knew it, 30 years had passed!

So Teddy picked up the guitar in the spring of ’05. Then, later that year I was contacted by a left-handed player, a young woman named Alicia, who wanted a true-lefty, like Albert’s. About that time – just as unexpected as the calls from Teddy and Alicia – I got a call from Steven Seagal, who told me he’d acquired Lucy, and wanted me to give her a physical. I’d watched a number of his movies, but didn’t know he was a serious blues guitarist. His friend and guitar tech, Peter Skaltsis, delivered Lucy to me.

What was it like, having it back in the shop?

It was a cool vibe having it at the same time I was building the new left-handed one. It even inspired me to start making one for myself – another true lefty, even though I’m a righty and probably won’t be able to play it.

So, have you changed your mind about building Lucy copies with the rest of the black walnut?

Oddly enough, about four years ago I pulled it out and cut it into enough to make a run of 20 of them. But to date, I’ve only made three – two righties, one lefty. The one I’ve been working on for two years now is a lefty. – Ward Meeker

This article originally appeared in VG_‘s June 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and_ Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Albert King – “As The Years Go Passing By” Live Sweden 19

Steven Seagal, Mojo Priest