World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) (original) (raw)

Global Guardian of Digestive Health. Serving the World.

World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Update August 2015

Review team

Charles Bernstein (Canada, Chair)

Abraham Eliakim (Israel)

Suliman Fedail (Sudan)

Michael Fried (Switzerland)

Richard Gearry (New Zealand)

Khean-Lee Goh (Malaysia)

Saeed Hamid (Pakistan)

Aamir Ghafor Khan (Pakistan)

Igor Khalif (Russia)

Siew C. Ng (Hong Kong, China)

Qin Ouyang (China)

Jean-Francois Rey (France)

Ajit Sood (India)

Flavio Steinwurz (Brazil)

Gillian Watermeyer (South Africa)

Anton LeMair (The Netherlands)

Contents

Contents

(Click to expand section)

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of idiopathic chronic inflammatory intestinal conditions. The two main disease categories are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), which have both overlapping and distinct clinical and pathological features.

The pathogenesis of IBD is incompletely understood. Genetic and environmental factors such as altered luminal bacteria and enhanced intestinal permeability play a role in the dysregulation of intestinal immunity, leading to gastrointestinal injury.

1.1 Global incidence/prevalence and East–West differences

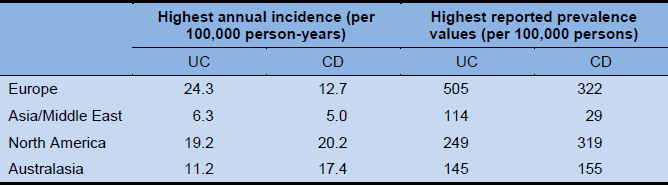

- A systematic review published in 2012 [1], including data from 167 population-based studies in Europe (1930–2008), 52 studies in Asia and the Middle East (1950–2008), and 27 studies in North America (1920–2004), reported the following incidence and prevalence figures. In time-trend analyses, 75% of CD studies and 60% of UC studies showed an increasing incidence, which was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The study did not include data from South America. The incidence of CD in South America reached an average of 1–3 per 100,000 rising to 3–4/100,000 in more developed urban areas in Brazil [2]. Although there are few epidemiologic data from developing countries, the incidence and prevalence of IBD are increasing with time and in different regions around the world — indicating its emergence as a global disease.

- In a recent comparative population-based study from Asia, the incidence of IBD [3] was found to vary throughout Asia, ranging from 0.54 per 100,000 to 3.44 per 100,000 persons.

- In 2004 in Australia, the age-standardized (WHO World Standard Population) incidence rates of IBD, CD, and UC were 25.2, 16.5, and 7.6/100,000/year, respectively [4]. In a population-based IBD study in Australia published in 2010 [5], the annual incidence rates were among the highest reported in the literature: 23.5–36.7 per 100,000 per year.

- A 2009 paper [6] gave prevalence data for UC of 64/100,000 and for CD of 21/100,000 in Japan.

Table 1 Highest annual incidence rates and reported prevalence rates for inflammatory bowel disease

The prevalence of CD appears to be higher in urban areas than in rural areas, and also higher in higher socio-economic classes. Most studies show that when the incidence first starts to increase, it is mostly among those of higher social class, but that the disease becomes more ubiquitous with time.

If individuals migrate to developed countries before adolescence, those initially belonging to low-incidence populations show a higher incidence of IBD. This is particularly true for the first generation of these families born in a country with a high incidence.

- One hypothesis for the difference in incidence between developed and developing nations is the “hygiene hypothesis,” which suggests that persons less exposed to childhood infections or unsanitary conditions lose potentially “friendly” organisms or organisms that promote regulatory T cell development, or alternatively do not develop a sufficient immune repertoire, as they do not encounter noxious organisms [7,8]. Such individuals are associated with a higher incidence of chronic immune diseases, including IBD.

- Other hypotheses for the emergence of IBD in developing nations include changes to a Western diet and lifestyle (including use of Western approaches to medication and vaccination) and the importance of such changes early in life.

- In developed countries, UC emerged first and then CD followed. In the past 20 years, CD has generally overtaken UC in incidence rates. In developing countries in which IBD is emerging, UC is typically more common than CD. In India, for example, there are reports of a UC/CD ratio of 8 : 1 (previously 10 : 1). One example of the rising incidence of CD once the diseases have been prevalent for some time is seen in Hong Kong, China, where the UC/CD ratio has dropped from 8 : 1 to 1 : 1 [9].

- The peak age of incidence of CD is in the third decade of life, with a decreasing incidence rate with age. The incidence rate in UC is quite stable between the third and seventh decades.

- There is a continuing trend toward an increasing incidence and prevalence of IBD across Asia (particularly in East Asia). Although this is occurring among developing nations, it is also being seen in Japan, a socio-economically advanced country.

- Although more females than males have CD, the incidence rates among young children have been higher in males than in females during the past decade, and over time we may see an equalization of the sex distribution. There is already a male predominance for CD in studies from East Asia. The sex ratio is already equal in UC.

1.2 Presenting features of IBD — East–West differences

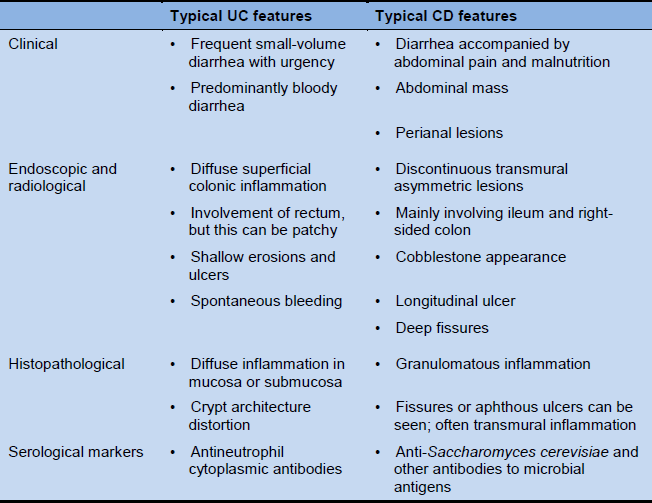

The presentations of CD and UC are quite similar in such disparate areas of the world as North America, South America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand: CD is distinguished from UC by disease proximal to the colon, perineal disease, fistulas, histologic granulomas, and full-thickness as opposed to mucosa-limited disease. In CD, granulomas are evident in up to 50% of patients and fistulas in 25%.

However, there are also differences in presentation between the East and the West. In East Asia, there is a higher prevalence of males with CD, ileocolonic CD, less familial clustering, lower rates of surgery, and fewer extraintestinal manifestations. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) associated with UC is less prevalent. Overall, the need for surgery is lower in Asian patients, at around 5–8%. However, there is a high rate of penetrating disease and perianal disease in Asia even at diagnosis, suggesting that complicated disease behavior is not uncommon in East Asia [3,10–12].

In Pakistan, there is much less extraintestinal disease in both UC and CD than is reported from the West (where up to 25% of patients have extraintestinal manifestations, if arthralgia is included). In Pakistan, few patients have perianal or fistulizing disease. In India, the age at presentation of CD is a decade later than in the West, colonic involvement is more common, and fistulization appears to be less common.

Tuberculosis is an important differential-diagnostic issue in developing countries.

Numerous genetic loci have been identified that contain susceptibility genes for IBD. Nearly all of these loci are of absolute low risk, but identifying them is important for the development of diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets in the future. Gene mutations known to be implicated in altering the predisposition to CD or UC have different distributions in different countries of the world, particularly where there are racial differences [13]. NOD2 mutations are not reported in any of the studies from Asia [14], whereas polymorphisms in the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily 15 gene (TNFSF15) have been found to be associated with CD in East Asians [15].

2. Clinical features

2.1 Symptoms

IBD is a chronic, intermittent disease. The symptoms range from mild to severe during relapses, and they may disappear or decrease during remissions. In general, the symptoms depend on the segment of the intestinal tract involved.

Symptoms related to inflammatory damage in the digestive tract

- Diarrhea:

- Stool may contain mucus or blood.

- Nocturnal diarrhea.

- Incontinence.

- Constipation:

- May be the primary symptom in UC limited to the rectum (proctitis).

- Obstipation with no passage of flatus can be seen in cases of bowel obstruction.

- Pain or rectal bleeding with bowel movement

- Bowel movement urgency

- Tenesmus

- Abdominal cramps and pain:

- In the right lower quadrant of the abdomen common in CD, or around the umbilicus, in the lower left quadrant in moderate to severe UC.

- Nausea and vomiting may occur, but more so in CD than UC.

General symptoms associated with UC and CD in some cases

- Fever

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Night sweats

- Growth retardation

- Primary amenorrhea

Extraintestinal manifestations

Extraintestinal manifestations include musculoskeletal conditions (peripheral or axial arthropathy), cutaneous conditions (erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum), ocular conditions (scleritis, episcleritis, uveitis), and hepatobiliary conditions (PSC).

2.2 Complications

Intestinal complications

- Proximal gastrointestinal involvement is a complication, or a different disease presentation. It may occur more often in children and in some adult ethnic groups (African-Americans, Ethiopians), but it is also sought more commonly in children, with whom gastroscopy is a routine early investigation, whereas in adults it is not [16].

- Hemorrhage: profuse bleeding from ulcers occurs in UC. Bleeding is less common in CD. Massive bleeding in CD is more often seen due to ileal ulceration than in colitis.

- 5–10% of individuals with CD show ulceration in the stomach or duodenum.

- Bowel perforation is a concern in CD, and in both CD (if the colon is involved) and UC if megacolon ensues.

- Intra-abdominal abscesses in CD.

- Strictures and obstruction (narrowing of the bowel may be due to acute inflammation and edema, or due top chronic fibrosis):

- Strictures in CD are often inflammatory:

* Inflammatory strictures can resolve with medical treatment.

* Scarring (fixed or fibrotic) strictures may require endoscopic or surgical intervention to relieve the obstruction. - Colonic strictures in UC are presumed to be malignant until proven otherwise.

- Strictures in CD are often inflammatory:

- Fistulas and perianal disease:

- These are a hallmark of CD.

* Surgical intervention is required in cases that do not respond to medical treatment, or when abscesses have developed. Sometimes surgical treatment should be pursued concomitantly with medical therapy, especially in instances of complex fistulas.

* There is a high risk of recurrence. - Fistulas to the urinary tract or vagina are not uncommon and can lead to pneumaturia or fecaluria, or passage of air from the vagina. This may result in urinary tract infection or gynecological inflammation.

- These are a hallmark of CD.

- Toxic megacolon:

- This is a relatively rare, life-threatening complication of colitis (characterized by dilation of the colon diagnosed on plain abdominal radiography) that requires aggressive medical therapy and urgent surgical intervention if there is no response within 24 h (more common in UC than CD).

- Malignancy:

- There is a significantly increased risk of colon cancer in UC later than 8 years after the diagnosis and with uncontrolled disease activity; there is a similar risk in CD if a substantial area of the colon is involved. The risk increases relative to disease duration, early age of disease onset, and if there is a family history of sporadic colorectal cancer. The overall rates of colorectal cancer in UC have been decreasing in recent reports [17], perhaps due to better use of drugs that reduce inflammation over time (chemoprevention) and also because of optimized surveillance [18,19].

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in UC is also associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer. PSC is also increased in CD, although it is more common in UC.

- There is an increased risk of small-bowel adenocarcinoma in small-bowel CD, but it is rare.

Extraintestinal complications

- Extraintestinal complications should be differentiated from extraintestinal manifestations, and they may be related to disease or to drugs used for IBD — e.g., drug-induced arthropathies (corticosteroids, biologicals); ocular complications (corticosteroid-induced glaucoma or cataracts); hepatobiliary complications (gallstones, fatty liver); renal complications (drug-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis); anemia (iron or vitamin B12 deficiency, or thiopurine-induced cytopenia); bone complications (osteoporosis and fractures); venous thromboembolic disease; and mood and anxiety disorders.

- They affect up to 25% of those with IBD, although 15–20% have arthralgias, while the remainder have frank inflammatory disease in other organ systems. Some complications may antedate the diagnosis of IBD, and some may run an independent course from the IBD (even colectomy in UC does not affect the course of ankylosing spondylitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis — although for many, arthralgia activity parallels the activity of the bowel disease).

3. Diagnosis of IBD

The diagnosis of IBD in adults requires a comprehensive physical examination and a review of the patient’s history. Various tests, including blood tests, stool examination, endoscopy, biopsies, and imaging studies help exclude other causes and confirm the diagnosis.

3.1 Patient history

- Ask about symptoms — diarrhea (blood, mucus), abdominal pain, vomiting, weight loss, extraintestinal manifestations, fistulas, perianal disease (in CD), fever.

- Inquire as to whether any of the presenting symptoms has occurred at any time in the past (not uncommonly, flares of disease have gone undiagnosed in the past).

- Duration of current complaints, nocturnal awakening, missing work or usual social activities.

- Inquire about possible extraintestinal manifestations — including, but not limited to, arthritis, inflammatory ocular disease, skin diseases, osteoporosis and fractures, venous thromboembolic disease.

- Identify whether mood disorders are present, or stressful situations known to precipitate IBD.

- Recent and past medical problems — intestinal infection.

- History of tuberculosis (TB) and known TB contacts.

- Travel history.

- Medications — antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and others like corticosteroids for acne.

- Family history (IBD, celiac disease, colorectal cancer, TB).

- Cigarette smoking.

3.2 Physical examination

- General:

- General well-being

- Pallor

- Cachexia

- Clubbing

- Nutritional status

- Pulse rate and blood pressure

- Body temperature

- Body weight and height

- Abdominal region:

- Mass

- Distension

- Tenderness, rebound, guarding

- Altered bowel sounds (obstruction)

- Hepatomegaly

- Surgical scars

- Perianal region:

- Tags

- Fissures

- Fistulas

- Abscess

- Digital rectal examination (assess for anal strictures, rectal mass)

- Extraintestinal inspection — mouth, eyes, skin, and joints:

- Aphthous ulcers

- Arthropathy

- Uveitis, episcleritis

- Erythema nodosum

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Sweet’s disease (acute neutrophilic dermatosis)

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (manifestations of chronic liver disease)

- Metabolic bone disease

3.3 Laboratory tests

Stool examination

- Routine fecal examinations and cultures should be carried out to eliminate bacterial, viral, or parasitic causes of diarrhea.

- Testing for Clostridium difficile (should be considered even in the absence of antecedent antibiotics) — should be carried out within 2 hours of passage of stools.

- A check for occult blood or fecal leukocytes should be carried out if a patient presents without a history of blood in the stool, as this can strengthen the indication for lower endoscopy. Where lower endoscopy is readily available, these tests are rarely indicated.

- Lactoferrin, α1-antitrypsin. The main reason for listing this test is to rule out intestinal inflammation, rather than using it as a positive diagnostic test. It may not be available in developing countries, but it can be undertaken relatively inexpensively and easily with rapid-turnaround slide-based enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) tests.

- Calprotectin — a simple, reliable, and readily available test for measuring IBD activity — may be better for UC than CD; the rapid fecal calprotectin tests could be very helpful in developing countries [20]. If available, a home test may be useful as a routine for follow-up.

Blood examination

- Complete blood count (CBC).

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and orosomucoid; levels correlate imperfectly with inflammation and disease activity.

- Electrolytes and albumin, ferritin (may indicate absorption or loss problems), calcium, magnesium, vitamin B12.

- Serum ferritin may be elevated in active IBD, and may be in the normal range even in the face of severe iron deficiency. Transferrin saturation can also be assessed to evaluate anemia. The soluble transferrin receptor (sTFR) assay is also a good measure of iron stores, although it is expensive (and also involves an acute-phase protein) and not commonly available.

- Decreased serum cobalamin — may indicate malabsorption.

- Liver enzyme and function testing — international normalized ratio (INR), bilirubin, albumin.

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — additional opportunistic infection work-up, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), immunoglobulin G (IgG) [21].

- Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA) and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) for cases of unclassified IBD.

- Positive p-ANCA and negative ASCA tests suggest UC.

- Negative p-ANCA and positive ASCA tests suggest CD.

- These tests are unnecessary as screening tests, particularly if endoscopy or imaging is going to be pursued for more definitive diagnoses. p-ANCA may be positive in Crohn’s colitis and hence may not be capable of distinguishing CD from UC in otherwise unclassified colitis. ASCA is more specific for CD. These tests may have added value when there may be subtly abnormal findings, but a definitive diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is lacking. They may also be helpful if considering more advanced endoscopic techniques such as capsule endoscopy or double-balloon endoscopy, such that a positive ASCA test may provide stronger reasons for evaluating the small bowel.

- ASCA may not be equally available or affordable everywhere. In countries in which TB is an important differential diagnosis, ASCA is not helpful for differentiating small-bowel CD from small-bowel TB. However, if both ASCA and interferon gamma release assays are available and the ASCA test is positive and the interferon gamma release assay is negative, the specificity for CD is high.

- There are several other antibody tests, mostly for microbial antigens, that increase the likelihood of CD either singly, in combination, or as a sum score of the ELISA results for a cluster of antibodies. These tests are costly and not widely available. The presence of these antibodies, including a positive ASCA, would increase the likelihood that an unclassified IBD-like case represents Crohn’s disease.

- Celiac antibody testing should be pursued unless presentations include obviously nonceliac features such as fistulas, perineal disease, and blood in the stool.

- It is recommended that thiopurine methyl transferase (TPMT) enzyme levels should be measured prior to initiating thiopurine therapy. In Caucasians, the rate of mutations at both TPMT alleles, resulting in inadequate TPMT levels, is approximately 0.3%. The rates of very low to unmeasurable TPMT levels in other ethnic groups is unknown.

- Serum levels of thiopurine metabolites and of circulating levels of biological agents (to date mostly only available for antibodies to TNF), as well as circulating levels of antibodies to biological agents, can help guide the dosage and monitoring of drug adherence.

Excluding intestinal TB in areas with a high pretest probability

- Tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test. (In some countries, such as Brazil, the PPD is considered to be positive when > 10 mm; in the USA, it is positive when > 5 mm)

- Serum PPD antibody test.

- Interferon gamma assays (QuantiFERON-TB, T-SPOT, TB test). The interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) has a high specificity for the diagnosis of TB. It may also be useful for differential diagnosis between gastrointestinal TB (GITB) and CD in Asian populations [22].

- All of these tests may be adversely affected by concurrent immunosuppression [23].

- Simple clinical parameters (such as fever, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and duration of symptoms) have the highest accuracy in differentiating CD from GITB [24]. This may be useful if resources are limited.

- The combination of endoscopic evaluation and simple radiologic and laboratory parameters (ASCA, IGRA) is a useful diagnostic aid in differentiating between CD and intestinal TB [25].

Histopathology

Biopsies are routinely obtained during endoscopy. It is important for the endoscopist to consider what specific question he or she is asking of the pathologist with each biopsy sample submitted for evaluation. Some of the important reasons for obtaining biopsies include:

- Assessment of crypt architecture distortion, “crypt runting,” increased subcryptal space, basal plasmacytosis. These are features of chronic colitis and would be atypical in acute infectious colitis.

- Assessment of noncaseating granulomas, which would be suggestive of Crohn’s disease. Large or necrotic/caseating granulomas should alert the physician to the a diagnosis of tuberculosis, especially in regions in which TB is endemic.

- Identifying histologic changes in areas of normal endoscopy to fully stage the extent of disease.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can be sought on tissue biopsy in patients receiving immunosuppressive agents or chronic corticosteroids — both for RNA, and on histology in colonic tissue. Serology can be useful as an adjunctive measure (CMV IgM).

- A search for dysplasia can be carried out if routine biopsies are being obtained for dysplasia surveillance, or if mass lesions are biopsied.

- Identifying lymphocytic colitis or collagenous colitis in an otherwise endoscopically normal-appearing colon. These diagnoses may coexist with small-bowel Crohn’s disease, and should be sought in patients with diarrhea.

3.4 Imaging and endoscopy

- Plain abdominal radiography:

- Can establish whether colitis is present and its extent in some cases.

- Used when bowel obstruction or perforation is expected.

- Excludes toxic megacolon.

- Barium double-contrast enema/barium small-bowel radiography:

- Not typically recommended in severe cases.

- Can be useful for identifying fistulas that arise from or bridge to the colon.

- Barium small-bowel radiography is still widely used to assess the gastrointestinal tract as far as the distal small bowel.

- Can provide an anatomic “road-map” prior to surgery.

- Sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy:

- Examine for ulcers, inflammation, bleeding, stenoses.

- Multiple biopsies from the colon and terminal ileum.

- Colonoscopy in severe or fulminant cases may be limited in extent, due to the increased risk of perforation.

- When there is a lack of response to usual therapy, these examinations can be used to assess for CMV infection if the patient is receiving chronic immunosuppressant medication, or for C. difficile infection if stool tests are equivocal.

- A screening colonoscopy for dysplasia surveillance is indicated after 8 years of UC or Crohn’s colitis.

The new consensus statement published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) should be consulted for recommendations on surveillance for and management of dysplasia in patients with IBD [26]. The new guidelines recommend chromoendoscopy as the primary surveillance modality, based on its better diagnostic yield in comparison with random biopsy approaches. However, there is ongoing debate on whether chromoendoscopy (with dye spraying) is better than high-definition white-light endoscopy. High-definition endoscopy has represented a clear advance for identifying raised or irregular lesions. In a recent randomized controlled trial, high-definition chromoendoscopy was found to significantly improve the rate of detection of dysplastic lesions in comparison with high-definition white-light endoscopy in patients with long-standing UC [27], although another trial reported no difference between chromoendoscopy and high-definition white-light endoscopy [28].

- Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy:

- In case of upper gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain). As upper gastrointestinal disease may be more common in pediatric CD, this is more routine in children.

- Capsule endoscopy:

- Helpful in patients with suspected CD and negative initial work-up.

- Allows evaluation of the entire small intestine, thus improving the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of IBD [29] — lesions found should be interpreted in the context of the differential diagnosis.

- May have a role in known CD — assessing disease distribution and the extent and response to therapy (mucosal healing).

- Its current role in UC is still debatable.

- For patients with CD who have stenoses or when there is uncertainty regarding stenosis, a patency capsule can be used first to determine whether there is a functional structure that would not allow passage of the real capsule endoscope.

- Rarely available and unaffordable in underprivileged countries.

- Double-balloon, single-balloon, and spiral enteroscopy:

- To assess small-bowel disease when other modalities have been negative and when a conditions is strongly suspected or if there is a need for biopsies; also to obtain tissue to rule out TB if the findings are beyond the reach of standard endoscopy.

- To treat small-bowel strictures or for assessment of obscure bleeding in CD.

- Rarely available in underprivileged countries.

- Other endoscopic advances:

- Magnification and chromoendoscopy have the potential to allow more accurate detection and characterization of dysplastic lesions and assessment of the severity of mucosal disease in comparison with white-light endoscopy [29].

- Although it can be time-consuming and has limited availability in some countries, methylene blue staining is relatively inexpensive [30]. It remains to be proven whether chromoendoscopy is in fact superior to recent high-resolution white-light endoscopy techniques.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP):

- If there is evidence of cholestasis, or suspected PSC.

- Cross-sectional imaging:

- Computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; including CT enterography and MRI enterography).

- Helpful for determining the extent and severity of disease and for assessing perforating complications of CD. Ultrasound and MRI are preferred, as the patients are often young and are likely to require repeat imaging over time.

- Ultrasound has high level of diagnostic accuracy for detecting CD, especially in the small bowel and in perianal CD, with relatively low cost and no radiation exposure [31]. It requires experienced staff.

- MRI has high levels of sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing CD in the small bowel and may be an alternative to endoscopy [32]. It is also useful for evaluating perianal disease. It is increasingly being used in pediatric patients and young adults due to the lack of radiation exposure and consequent ability to repeat the tests safely.

- Has replaced barium meal enteroclysis in centers with the appropriate expertise [33].

- MRI of the pelvis is considered the gold standard method for assessing perineal Crohn’s fistulas. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) can be considered if the expertise is available, but its accuracy may be limited by restricted views.

- Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA):

- For assessing bone mineral density in selected cases.

- Chest radiography:

- To exclude pulmonary TB and also to allow a search for free air under the diaphragm in case of perforation.

Note: it is important to minimize diagnostic medical radiation exposure, due to the potential risk of radiation-induced malignancy.

3.5 Diagnosis in pediatric patients

The European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) has published the revised Porto criteria for the diagnosis of IBD in children and adolescents [34]. The revised criteria are based on the original Porto criteria and the Paris classification of pediatric IBD, incorporating novel data such as serum and fecal biomarkers. The criteria recommend upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy in all suspected cases of pediatric IBD, with magnetic resonance enterography or wireless capsule endoscopy of the small intestine. Imaging is not necessary if typical UC is diagnosed using endoscopy and histology.

4. Cascade for IBD diagnosis

4.1 Cascade 1 — choices for diagnosis relative to available resources

Limited resources available

- Physical examination.

- Stool tests for infective sources, fecal leukocytes.

- CBC, serum albumin.

- HIV and TB testing in high-risk populations — and other opportunistic infection work-up, HBV, HCV, chest X-ray (CXR).

- Flexible full-length colonoscopy and ileoscopy with biopsies if histological interpretation is available.

- If endoscopy is not available but barium studies are, then both a small-bowel barium study and a barium enema should be obtained.

Medium resources available

- Physical examination.

- Stool tests for infection.

- Stool for fecal leukocytes, fecal calprotectin (not necessary if endoscopy available, but may help select for further investigation including with endoscopy).

- CBC, serum albumin, serum ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP).

- HIV and TB testing in high-risk populations — serology to HAV, HBV in patients with known IBD in order to vaccinate if necessary before therapy. Opportunistic infection work-up, HBV, HCV, VZV IgG, chest X-ray (CXR).

- Colonoscopy or ileoscopy, if available.

- Abdominal ultrasound scan.

- CT scan of the abdomen.

Extensive resources available

- Physical examination.

- Stool tests for infection.

- CBC, serum albumin, serum ferritin, CRP.

- HIV and TB testing in high-risk populations — serology to HAV, HBV in cases with known IBD to vaccinate prior to therapy, if needed. Opportunistic infection work-up, HBV, HCV, VZV IgG, chest X-ray (CXR).

- Colonoscopy and ileoscopy.

- Abdominal ultrasound scan.

- Abdominal MRI is preferable to abdominal CT, due to the lack of radiation exposure.

- TB polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and culture are essential during lower endoscopy in areas with a high prevalence of TB.

- If there is uncertainty whether the patient has small-bowel disease, cross-sectional imaging with MRI, small-bowel capsule endoscopy, or CT should be carried out.

- Barium enema if a colonic fistula is expected and not identified on cross-sectional imaging, or if colonoscopy is incomplete.

- In the setting of incomplete colonoscopy, CT colonography has become a preferred choice for examining the entire colon. Some radiology units have reservations about pursuing this technique in the setting of CD. Colon capsule studies are another alternative in cases of incomplete colonoscopy, unless a colonic stricture is known or highly likely.

- Capsule endoscopy if the suspected diagnosis of CD is still unclear.

- Double-balloon endoscopy (antegrade or retrograde, depending on the suspected site) if areas of the mid–small bowel.

5. Evaluation

5.1 Diagnostic criteria

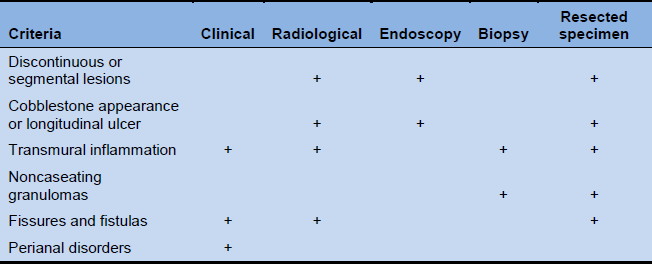

Table 2 World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for Crohn’s disease

Differentiating between UC and CD

Table 3 Features for differentiating between UC and CD

Diagnostic considerations

- Patients should be followed up for 3–6 months after a first attack if characteristic clinical, radiological, endoscopic, or histopathological features are lacking. Repeat colonoscopy can be considered after 10–12 weeks to ensure healing, which is expected in intestinal TB and potentially in CD.

- Treatment for TB should be administered and its effects should be observed in patients in whom there are difficulties in differentiating between CD and intestinal TB. Treatment for CD and TB should not be carried out simultaneously.

- Colonoscopy findings of diffuse inflammatory changes and negative stool cultures are not sufficient for a diagnosis of UC. This requires chronic changes over time (i.e., 6 months, in the absence of other emerging diagnoses) and signs of chronic inflammation histologically.

- Surveillance for colorectal cancer should be implemented in patients with long-standing UC and CD colitis.

- The sigmoidoscopic component of the Mayo Score and the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity show the greatest potential for reliable evaluation of endoscopic disease activity in UC [35] — but these are still mostly used in clinical trials.

5.2 Differential diagnosis

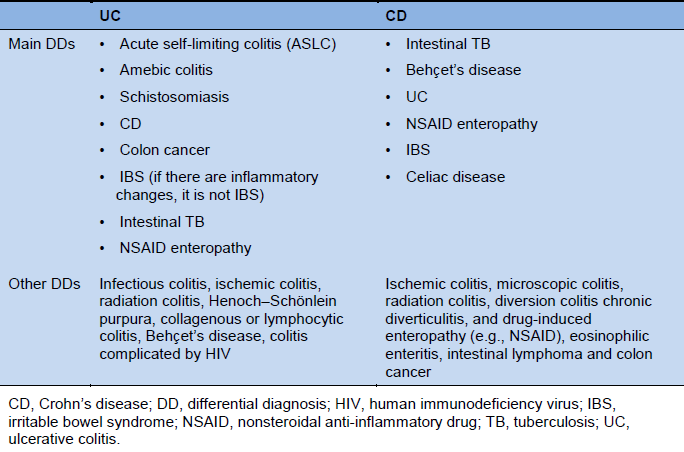

Table 4 Main differential diagnoses for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

IBD and intestinal tuberculosis

- Intestinal TB must be excluded before a diagnosis of IBD is made.

- A causal association between Mycobacterium paratuberculosis and IBD remains unproven.

- In high-risk populations or jurisdictions, if TB cannot be excluded, a trial of anti-TB therapy is justified and corticosteroids should be withheld.

- The sequences of symptoms occur as TB: fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea; CD: abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever (the latter is often absent).

- In the differential diagnosis between TB and CD, TB has a continuous course, while there is a history of remissions and relapses in CD.

- Ascites and hepatosplenomegaly may be present in TB, but are both uncommon in CD.

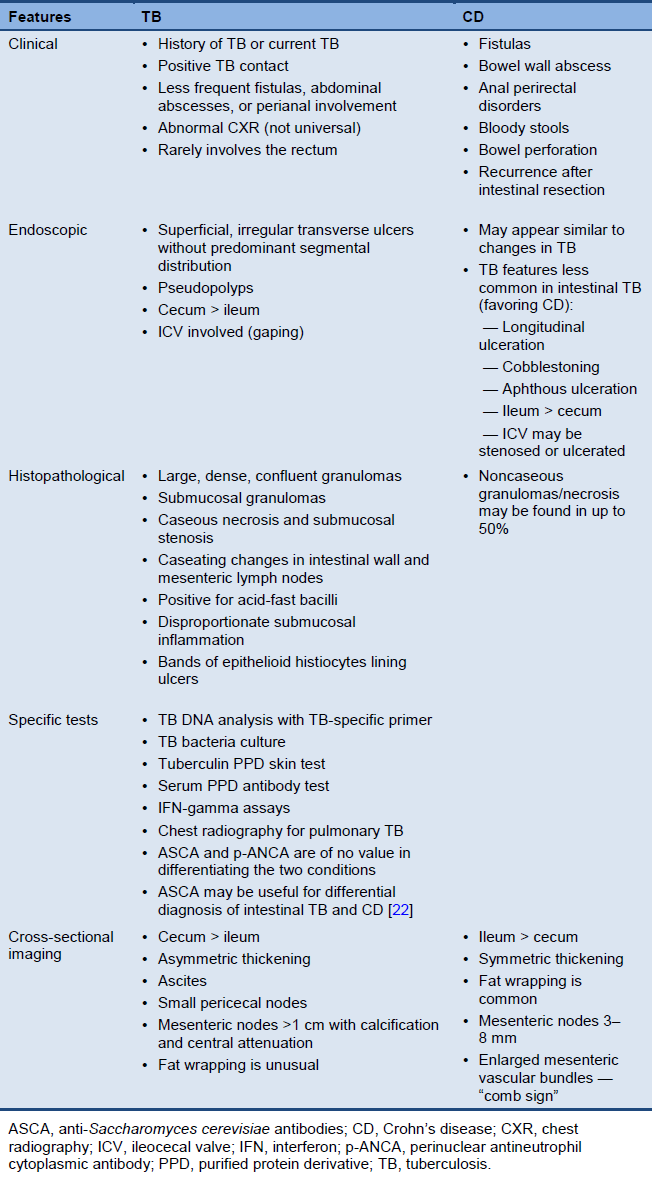

Table 5 Distinguishing between tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease

6. Management of IBD

6.1 Introduction

It is important for the patient to be provided with an explanation about the disease and individual information. Active patient participation in decision-making is encouraged.

IBD management often requires long-term treatment based on a combination of drugs to control the disease. Clinicians should be aware of possible drug interactions and side effects. Often, patients will require surgery, and close collaboration is required between surgeons and physicians to optimize the patient’s therapy.

IBD management should be based on:

- UC vs. CD (although this is less important for early aspects of treatment)

- Disease location and phenotype

- Severity

- Comorbidities and complications

- Individual symptomatic response

- Tolerance to medical intervention

- Patient access to diagnostic and treatment options

- Past disease course and duration, with number of relapses in a calendar year

The goal of treatment is to:

- Improve and maintain patients’ general well-being (optimizing the quality of life, as seen from the patient’s perspective)

- Treat acute disease:

- Eliminate symptoms and minimize side effects and long-term adverse effects

- Reduce intestinal inflammation and if possible heal the mucosa

- Maintain corticosteroid-free remissions (decreasing the frequency and severity of recurrences and reliance on corticosteroids)

- Prevent complications, hospitalization, and surgery

- Maintain good nutritional status

Diet and lifestyle considerations:

- The impact of diet on inflammatory activity in UC/CD is poorly understood, but dietary changes may help reduce symptoms:

- During increased disease activity, it is appropriate to decrease the amount of fiber. Dairy products can be maintained unless not tolerated.

- A low-residue diet may decrease the frequency of bowel movements.

- A high-residue diet may be indicated in cases of ulcerative proctitis (disease limited to the rectum, where constipation can be more of a problem than diarrhea).

- There are limited data suggesting that a reduction of dietary fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) may reduce the symptoms of IBD [36].

- Dietary or lifestyle changes may reduce inflammation in CD:

- A liquid diet, pre-digested formula, or nothing by mouth (NPO status) may reduce obstructive symptoms. Exclusive enteral nutrition can settle symptoms in inflammatory disease, especially in children; however, how it affects the inflammation is unknown, since relapse upon stopping enteral nutrition is common unless some other intervention has been undertaken. It may affect the gut microbiome, which reverts to baseline once the enteral nutrition is stopped and the usual table diet is reinitiated.

- Enteral nutrition should be considered as an alternative to conventional corticosteroids to induce remission of CD in children in whom there is a concern about growth [37] or when immunosuppression is not appropriate —e.g., in difficult-to-control sepsis.

- Smoking cessation benefits patients with CD in relation to their disease course and benefits UC patients from a general health point of view (smoking cessation is associated with flaring of UC).

- Dietary fiber has potential efficacy for treatment of IBD. There is limited, weak evidence for efficacy of ispaghula in maintenance of remission of UC and germinated barley in active UC [38].

- Reduction of stress and better stress management may improve symptoms or the patients’ approach to their disease. The assistance of a mental health worker may be useful, and attention to comorbid psychiatric illness is imperative.

6.2 Drugs in IBD management

Aminosalicylates — anti-inflammatory agents

- This group includes:

- 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), mesalazine (U.S. Adopted Name mesalamine).

- Preparations available in North America and Western Europe for oral use: sulfasalazine, mesalamine, olsalazine, mesalazine, balsalazide (in pills, granules, or multi-matrix preparations); for rectal use: mesalamine enemas (liquid or foam) and suppositories.

- Useful both for treating colitis flare-ups and maintenance of remission.

- 5-ASA for UC treatment during remissions:

- Oral or rectal 5-ASA.

- Combination therapy of oral and topical 5-ASA. Combined oral and topical 5-ASAs (mesalamine and sulfasalazine) are more beneficial than oral 5-ASAs alone for remission of mild to moderate active UC [39].

- Rectal 5-ASA is superior to rectal corticosteroids.

- Intermittent topical 5-ASAs are superior to oral 5-ASAs for preventing relapse of quiescent UC [39] for proctosigmoiditis patients.

- Data on 5-ASA in CD remain limited:

- In patients with mild ileocecal or right-sided colonic CD who decline or cannot tolerate corticosteroids, or in whom corticosteroids are contraindicated, 5-ASA should be considered for a first presentation or a single inflammatory exacerbation in a 12-month period [37].

- Do not offer 5-ASA for moderate to severe CD or exacerbations or for extensive small-bowel disease or disease with penetrating or fibrostenosing complications [37].

- In CD, sulfasalazine and mesalazine/mesalamine are presumed to be mainly effective in disease affecting the colon. However, this has not been specifically studied.

- Patients receiving sulfasalazine should take folic acid.

- It is important to use adequate doses: 2.0–4.8 g/day for active disease, ≥ 2 g/day for maintenance. However, the evidence for a dose-response effect for 5-ASA beyond 2 g/day is weak.

Corticosteroids

- These usually provide significant suppression of inflammation and rapid relief of symptoms [40].

- Corticosteroids induce remission in patients with a first presentation or a single inflammatory exacerbation of CD within a 12-month period [37].

- They have no role in the maintenance of remission.

- Side effects limit (long-term) use.

- Concurrent use of calcium and vitamin D is recommended, as well as monitoring of blood glucose and arterial blood pressure.

- In patients with distal ileal, ileocecal, or right-sided CD who decline or cannot tolerate corticosteroids, or in whom they are contraindicated, budesonide should be considered for a first presentation or a single inflammatory exacerbation within a 12-month period [37].

- Budesonide may have fewer side effects than conventional corticosteroids [37].

- Do not offer budesonide for severe CD or exacerbations [37].

- The route of administration depends on the location and severity of the disease:

- Intravenous (methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone).

- Oral (prednisone, prednisolone, budesonide, dexamethasone).

- Rectal (enema, foam preparations, suppository).

Immune modifiers — thiopurines

- Thiopurines are no more effective than placebo for inducing remission of CD or UC [41]; they are effective for maintenance of remission induced by corticosteroids [41].

- Do not offer azathioprine or mercaptopurine for CD or UC if thiopurine methyltransferase activity (TPMT) is deficient. Use at a lower dose if TPMT activity is below normal [37,42].

- If TPMT measurement is not available, the thiopurine dose should be escalated from 50 mg to the full dose while monitoring the blood count. Asians appear to require lower doses of thiopurine to achieve efficacy, and the full dosage is usually limited by the development of cytopenia.

- The addition of azathioprine or mercaptopurine to conventional corticosteroids or budesonide should be considered, in order to induce remission of CD if there are two or more inflammatory exacerbations within a 1-year period, or if the corticosteroid dose cannot be tapered and eliminated [37]. It may also be considered if there are predictors of poor outcome even at the time of diagnosis (age < 40, corticosteroids for first flare, perianal disease, smoking, perforating phenotypes).

- Thiopurines are associated with low rates of serious infection [41], but should be monitored more closely in the elderly [43].

- Thiopurines increase the risk of lymphoma, although the extent of the increase is debated [41]. Their use is also associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

- Thiopurines in particular are associated with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), most likely by promoting viral reactivation through inhibition of natural killer and cytotoxic T cells [44].

- Patients should be monitored for neutropenia if they are taking azathioprine or mercaptopurine [37], even if TPMT enzyme levels are normal [43].

- Azathioprine is used in resource-poor countries in patients with CD and UC because it is cheap, available, and appears to be safe. Patients often cannot afford 5-ASA and use corticosteroids, and present with severe complications; azathioprine is a better choice than corticosteroids.

- Thiopurine metabolite tests are not available in many countries, but where available can help explain the lack of response.

Immune modifiers — calcineurin inhibitors

- Cyclosporine A (CSA) or tacrolimus in UC and tacrolimus in CD.

- The tacrolimus level should be measured and a trough of 10–15 ng/L [45] should be aimed for.

- Use of CSA is limited to acute (corticosteroid-refractory) severe colitis.

Calcineurin inhibitors are reserved for special circumstances.

- Use of CSA is limited almost exclusively to patients with acute severe colitis.

- Use of tacrolimus in UC or CD in which other proven therapies have failed.

- Calcineurin inhibitors should be discontinued within 6 months to limit nephrotoxicity, and alternative immunosuppressives such as azathioprine (AZA), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), or methotrexate (MTX) will therefore be required if CSA is being considered.

- There is a high colectomy rate 12 months after the introduction of CSA.

- After intravenous CSA, there should be a switch to oral therapy when a clinical response is achieved, and 6-MP, AZA, or MTX should be added.

Immune modifiers — methotrexate (MTX) in CD

- Methotrexate is more effective than placebo for induction of remission of CD [41] and for maintenance of remission induced by corticosteroids [41,46].

- The addition of methotrexate to conventional corticosteroids or budesonide should be considered in order to induce remission of CD if patients cannot tolerate azathioprine or mercaptopurine, or in patients in whom TPMT activity is deficient if there are two or more inflammatory exacerbations within a 1-year period, or if the corticosteroid dose cannot be tapered [37].

- Methotrexate should only be considered in order to maintain remission of CD in patients who needed methotrexate to induce remission, or who cannot tolerate or have contraindications to azathioprine or mercaptopurine [37] — MTX should also be avoided in young women because of pregnancy issues.

- Methotrexate is a good option if concomitant therapy with an anti-TNF agent is undertaken. It has been shown to not have any advantage over placebo in inducing and maintaining remission in persons with CD who have received high-dose corticosteroids and an induction and maintenance regimen with infliximab over 1 year [47]. However, co-administration with methotrexate can reduce antibody formation to anti-TNF therapy, and this will likely increase the sustained response to the anti-TNF. It is considered that the likelihood of increasing the risk for lymphoma with methotrexate as a single or combination therapy is less than when thiopurines are used. This risk is considered to be small [41].

- Co-administration of folic acid is recommended.

- Hepatotoxicity with methotrexate treatment for IBD is typically mild and reversible on stopping the drug. Patients should be monitored for hepatotoxicity at initiation and during treatment with methotrexate [48].

- The use of methotrexate in patients with UC is a matter of debate. The recent METEOR study [49] in France suggested a negative result, but the enrollment was of a very inactive group and some of the results were suggestive of a positive outcome. Hence, it may be a viable inexpensive option when there are few or no other options.

Immune modifiers: uses

- Can be used to reduce or eliminate corticosteroid dependence in patients with IBD.

- Can be used in selected patients with IBD when 5-ASAs and corticosteroids are either ineffective or only partly effective.

- Can be used to maintain remission in CD and in UC when 5-ASAs fail.

- Can be used in for primary treatment of fistulas.

- Are an alternative treatment for CD relapses after corticosteroid therapy.

- Can be used in for corticosteroid dependence, to maintain remission and allow withdrawal of corticosteroids.

- Either thiopurines or methotrexate can be used concurrently with biologic therapy to enhance effectiveness and reduce the likelihood of antibody formation.

Immune modifiers — important notes

- Do not offer azathioprine, mercaptopurine or methotrexate monotherapy to induce remission of CD or UC [37].

- The onset of action is relatively slow for thiopurines and MTX. It takes approximately 3 weeks for the dosage of thiopurines to reach blood homeostasis, and dosing can therefore be accelerated with proper monitoring. The onset of action is rapid (< 1 week) for CSA.

- Thiopurines are not suitable for acute flare-ups. CSA can be effective in acute severe UC.

- Before AZA or 6-MP is started, measurement of the thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) enzyme level (phenotype) will help to guide the dosage, and if enzyme levels are very low, then the risk may be too high for these drugs to be used. Where this test is not available, a CBC needs to be obtained at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and every 3 months thereafter. Even where the test is available, quarterly CBCs are still indicated.

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents

- This may be the first-line therapy in patients who present with aggressive disease and in those with perianal CD.

- Infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe CD when there is an inadequate response to standard medications. Infliximab and adalimumab have been approved in Canada and Europe.

- Infliximab and adalimumab show a better clinical response and better remission and mucosal healing than placebo, with no increase in adverse effects [41,50].

- Infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab are effective in maintaining remission of CD induced by anti-TNF agents [41].

- Infliximab (IFX) is used for rescue therapy in corticosteroid-refractory severe UC.

- The effects of intravenous IFX treatment last for approximately 8 weeks; regular scheduled dosing leads to better remission rates than episodic therapy. When there is a suboptimal response, the dosage can be increased from 5 mg/kg to 10 mg/kg, or the interval can be reduced. Other dosage adjustments can be tailored to drug levels. Adalimumab and certolizumab are administered subcutaneously every 2 and 4 weeks, respectively. In the case of adalimumab, dosing can be increased to weekly if there is a suboptimal response.

- The value of combination therapy with thiopurines in both CD and UC has been confirmed in the SONIC and SUCCESS studies. Concomitant therapy with MTX is of unproven value, although in patients with rheumatoid arthritis it is known to reduce immunogenicity when used concomitantly with infliximab. In resource-poor units, regular scheduled maintenance therapy often remains a distant dream, and episodic therapy is currently the only option (with the inherent issue of immunogenicity); see below.

- Concomitant administration of immunomodulatory agents reduces the risk of infliximab antibody development and the risk of infusion reactions [51]. It may be useful when administered with other anti-TNF agents, but this has not been formally tested — there is a concern, though, about the use of combined therapy (thiopurines + anti-TNF) in young male patients, because of the increased risk of hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma [52].

- Infliximab is the only proven therapy in the treatment of fistulas, on the basis of adequately powered randomized controlled trials. Adalimumab is also useful for fistulas, but these data are only available from subgroups in larger CD studies not specifically designed to assess the fistula response.

- Infliximab treatment reduces hospitalization and surgery rates in patients with IBD. This significantly reduces the costs associated with the disease [53].

- There is only a small increase in malignancy in anti-TNF users [54].

- The risk of lymphoma is very low, but this remains a concern. Other cancers may be increased [41], especially nonmelanoma skin cancers and possibly melanoma.

- Treatment of IBD with infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab significantly increases the risk of opportunistic infections in comparison with placebo [55].

- The risk of minor and serious infections is of concern. Anti-TNF agents are associated with low rates of serious infection, but they are associated with opportunistic infections, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, and listeriosis [41]. There is an increased risk of reactivation of latent TB and of hepatitis B, which is endemic in many parts of the developing world.

- If treatments fail or the patients become intolerant of one anti-TNF agent, a second anti-TNF agent can be effective [56].

- Golimumab received regulatory approval in 2013 for the treatment of moderate to severe UC. There is no increase in adverse effects compared with placebo [50].

- Infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab all induce a sustainable clinical response in IBD. None of these agents has been proven to be superior to the others, although the data are more robust with infliximab, especially in UC [57,58].

- In patients treated with infliximab, infliximab antibodies lead to a 2–6-fold increase in the risk of infusion reactions [51,55].

- Therapeutic drug monitoring (which includes both measurement of circulating drug levels and also measurement of antibodies to the drug) is more widely available for infliximab than any other anti-TNF. It can help determine the cause of a secondary loss of response and may be adopted in dose reduction strategies.

- There has been debate as to whether preoperative use of anti-TNFs increases the surgical risk or the rate of postoperative complications. On balance, this does not seem to be an important issue, and preoperative use of anti-TNFs should not be a deterrent against a surgical intervention if it is needed.

Adhesion molecule antagonists

- Vedolizumab (an antibody to alpha 4-beta 7) has recently been approved for the treatment of UC and CD and is effective at both inducing and maintaining remission. It has few side effects and no known risk for malignancy.

Antibiotics

- Metronidazole and ciprofloxacin are the most commonly used antibiotics in CD.

- Antibiotics are used to treat CD complications (perianal disease, fistulas, inflammatory mass, bacterial overgrowth in the setting of strictures).

- There has never been an adequately sized randomized controlled trial proving the efficacy of metronidazole and/or ciprofloxacin in perineal fistulas, but these are typically first-line therapies.

- There is an increased risk for _C. difficile_–associated disease (CDAD), and patients presenting with a flare of diarrheal disease should be checked for C. difficile and other fecal pathogens.

- There are no data showing that any antibiotics are effective in UC, but they are used in the setting of fulminant colitis.

Probiotics

- IBD may be caused or aggravated by alterations in the gut flora.

- While many patients may use probiotics, there is no evidence that they are effective in either UC or CD. VSL#3, which is a combination of eight probiotics, induces and maintains remission of UC [59], and may be as effective as 5-ASA. However, no such benefit has been demonstrated for CD [60].

- There are a few studies that suggest that Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is not inferior to low-dose 5-ASA, but response rates were low in these studies. VSL#3 has been shown to reduce flares of pouchitis (post-ileoanal pouch procedure for UC) in two Italian studies and in one study from both Italy and the UK.

Experimental agents (examples)

- UC: anti-adhesion molecules, anticytokine therapies, anti-kinase therapies, anti-inflammatory proteins.

- CD: anti-adhesion molecules, anticytokine and T cell marker therapies, anti-kinase therapies, mesenchymal stem cells.

- Antisense oligonucleotides/blockers of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) inhibition

Symptomatic therapy and supplements

- Antidiarrheals such as loperamide (Imodium) if colitis is not fulminant; cholestyramine if the patient has previously undergone ileal resection.

- Analgesics such as acetaminophen, or even codeine if acetaminophen is insufficient. However, narcotic use should be avoided, as it is associated with increased mortality in patients with IBD [61].

- Nutritional supplementation for those with malnutrition, or during periods of reduced oral intake.

- Vitamin B12 replenishment for those with deficiency.

- Vitamin D supplementation if the local area does not allow sun exposure for much of the year— and for patients on thiopurines who are using sunscreens.

- Routine vitamin D and calcium supplementation for corticosteroid users.

- Routine multivitamin supplementation for all.

- For chronic iron-deficiency anemia, parenteral iron should be administered (either as weekly intramuscular shots or dosing with intravenous iron) if oral iron is not tolerated.

Disease status and drug therapy

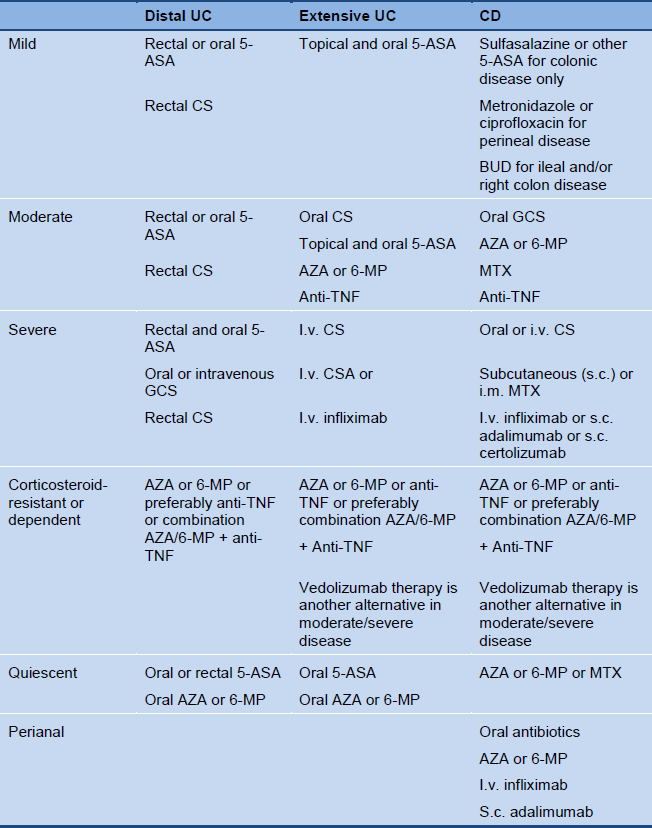

Table 6 Overview of disease status and drug therapy

6.3 Surgical treatment

IBD patients may require hospitalization for surgery or for medically refractory disease— this accounts for at least half of the direct costs attributable to IBD.

Surgery in CD

- 70–75% of CD patients require surgery at some point to relieve symptoms if drug treatment fails, or to correct complications although the incidence of surgery in CD is falling.

- Surgery should be considered as an alternative to medical treatment early in the disease course for short-segment CD limited to the distal ileum [37].

- Surgery is rarely curative in CD; the condition recurs frequently after surgery. However, surgery can lead to long-lasting remission in some patients with CD. After surgery, azathioprine and metronidazole should be considered for at least 3 months, as this has been shown to reduce recurrence.

- Laparoscopic ileocecal resection has perioperative morbidity rates similar to or better than those with open surgery for treatment of CD. Convalescence is shorter with the laparoscopic approach, although the operating time is longer [62].

- Balloon dilation may be useful in patients with a single stricture that is short, straight, and accessible by colonoscopy [37]. It should be ensured that abdominal surgery is available to manage complications or failure of balloon dilation [37].

- Surgical options are:

Surgery in UC

- 25–30% of UC patients may require surgery if medical treatment is not completely successful, or in the presence of dysplasia.

- Surgical options are:

- Total proctocolectomy plus permanent ileostomy.

- Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA).

- Segmental resection can be considered for localized neoplasms in the elderly, or in patients with extensive comorbidity.

Surgery and medication

Corticosteroids:

- The dosage should be gradually reduced to prevent surgical complications.

- All patients undergoing an ileal or ileocecal resection with a primary anastomosis for CD should receive metronidazole for at least 3 months postoperatively.

Azathioprine:

- No increased risk in a perioperative setting.

- Azathioprine and mercaptopurine reduce the need for surgery in CD by 40%. However, even with treatment with these drugs, approximately 20% of patients with CD still require surgery at 5 years after diagnosis [64].

- Azathioprine or mercaptopurine should be considered in order to maintain remission of CD after surgery in patients with adverse prognostic factors [37]. Colonoscopy should be considered 6 months postoperatively to escalate therapy on the basis of the Rutgeerts score [61,65].

Perioperative anti-TNF-α therapy with infliximab, adalimumab, or certolizumab:

- An increased risk for emergency colectomy is suspected for acute severe colitis.

- There is no increased risk in CD.

- Preoperative infliximab increases the incidence of early postoperative complications, particularly infection, in patients with CD. However, the results need cautious interpretation [66].

- Postoperative maintenance in CD with 6-MP/AZA to reduce the frequency and severity of recurrences. The best data for maintenance are for metronidazole — it is inexpensive and can be considered in resource-poor settings (although limited by dysgeusia and neuropathic side effects). In contrast, the data for 5-ASA are weak and it is more expensive, although much better tolerated than metronidazole.

- The importance of stopping smoking should be emphasized to patients — this is the single most effective approach patients can take in order to reduce recurrences in CD.

- Do not offer budesonide or enteral nutrition to maintain remission of CD after surgery [37].

6.4 Other management options

- Marijuana is often used by patients with either CD or UC. Although anecdotally it may improve symptoms, controlled trials are lacking. A small study from Israel suggested some benefit.

- Many patients stop their therapies over time and remain well in complete remission for extended periods. Investigators in Manitoba, Canada, showed that by 5 years of disease, up to 50% of patients may not be using any prescription medications specifically for their IBD. Many of them are in remission and not requiring therapy.

- Granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis (GMAA) is safe and effective in the treatment of UC, in comparison with corticosteroid therapy. There are odds ratios (OR) of 2.23 in favor of GMAA for efficacy and 0.24 in favor of GMAA for adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effects are reported to be headache and flushing. None of the patients discontinued treatment [67].

7. Cascades for IBD management

7.1 Cascade 2 — UC management

Limited resources available

- In endemic areas and when there is limited access to diagnosis, a course of anti-ameba therapy should be administered.

- Sulfasalazine (least expensive) for all mild to moderate colitis and for maintenance of remission. Different mesalazine preparations are available, including Asacol 800 mg, Lialda (U.S.), and Mezavant (Europe) 1200 mg pills, and Pentasa 2 g sachets. These larger once-daily doses can facilitate better adherence, with no sulfa side effects.

- Corticosteroid enemas (especially with a foam vehicle, which is easier to retain than liquid enemas for distal colon disease). Corticosteroid enemas can sometimes be made with locally available resources, sometimes at lower cost.

- Oral prednisone for moderate to severe disease (acute severe disease requires intravenous corticosteroids).

- If acute severe colitis is unresponsive to intravenous corticosteroids or the patient has chronic corticosteroid-resistant or corticosteroid-dependent colitis, colectomy should be considered. This decision needs to be made in a timely fashion in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Either the Oxford or Swedish predictors of outcome on day 3 of intravenous corticosteroids can be considered.

- CMV and C. difficile should be actively sought in patients with refractory disease.

- Azathioprine for corticosteroid dependence. Methotrexate can be considered if azathioprine is not available or if there is intolerance, but this is unproven in UC.

Medium resources available

- Sulfasalazine can be used for mild to moderate colitis.

- Asacol 800 mg, Lialda/Mezavant 1200 mg pills, and Pentasa 2 g sachets are now available and can facilitate better adherence, with no sulfa side effects.

- 5-ASA enemas or suppositories for distal disease. These can be used for remission maintenance in distal disease in lieu of oral 5-ASA. Steroid enemas are also an option, but typically not for maintenance.

- Combination therapy with oral and rectal 5-ASA may be more effective in active distal disease or even active pancolitis.

- If remission is not maintained with 5-ASA, then azathioprine or 6-MP/AZA should be considered; if azathioprine fails, anti-TNF or vedolizumab should be considered.

- If biological agents are available, then depending on the severity of the illness their use may be indicated instead of trials of immunomodulator monotherapy.

Extensive resources available

- Cyclosporine can be considered in patients with acute severe colitis.

- Infliximab can be considered for acute severe colitis or moderately severe corticosteroid-dependent or corticosteroid-resistant colitis — as can adalimumab.

- Infliximab or vedolizumab intravenously, or Humira (adalimumab) or golimumab subcutaneously, are options for ambulatory patients with moderate to severe disease.

- Azathioprine or 6-MP — in case of azathioprine failure, anti-TNF or vedolizumab should be considered.

7.2 Cascade 3 — CD management

Limited resources available

- In endemic areas and when there is limited access to diagnosis, a course of anti-ameba therapy should be given.

- In endemic areas for TB, a trial of anti-TB therapy for 2–3 months should be considered in order to determine the response.

- Sulfasalazine (least expensive) for all mild to moderate colitis and for maintenance of remission.

- Corticosteroid enemas for distal colon disease. Corticosteroid enemas can sometimes be made with locally available resources, sometimes at lower cost.

- Trial of metronidazole for ileocolonic or colonic disease.

- Oral prednisone for moderate to severe disease.

- If there is a short segment of small-bowel disease, surgery should be considered.

- Azathioprine or methotrexate.

- Metronidazole for short-term (3 months) postoperative maintenance after an ileal resection with a primary ileocolonic anastomosis.

Medium resources available

- Treat TB and parasites first when diagnosed.

- Sulfasalazine for mild to moderate active colonic CD.

- Budesonide can be used for mild ileal or ileocolonic disease (right colon).

- If remission is not maintained after a course of corticosteroids or if predictors of poor outcome CD are present, azathioprine (or 6-MP/AZA) should be considered; in case of azathioprine failure, methotrexate should be considered. Anti-TNF can also be considered instead of AZA/6-MP or MTX, and these therapies can be optimized when combined (as proven for AZA/6-MP + infliximab).

- Therapeutic monitoring of drug and antibody levels to anti-TNF agents can guide therapy, especially in the setting of secondary loss of response or if one is wanting to consider a dose reduction because of prolonged remission.

Extensive resources available

- Infliximab or adalimumab or certolizumab can be considered for moderate to severe corticosteroid-dependent or corticosteroid-resistant disease.

- Immunosuppressive drugs, such as 6-MP and AZA, can also be very helpful in the treatment of fistulas in CD. These agents have been shown to enhance the response to infliximab and may be useful when used concomitantly with other anti-TNF agents by reducing their immunogenicity.

- Vedolizumab can be considered when anti-TNF fails.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring for biological agents, as noted above.

7.3 Cascade 4 — perianal fistulas

Limited resources available

- Metronidazole.

- Surgery, if an abscess is present.

- Ciprofloxacin.

- A combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. These antibiotics can be used intermittently for maintenance of fistula closure if tolerated over the long term.

- Surgery — should be considered early and if long-term maintenance of antibiotics is required.

- Combined medical and surgical therapy provides the best outcome.

Medium resources available

- Metronidazole.

- Surgery, if an abscess is present.

- Ciprofloxacin.

- A combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. These antibiotics can be used for maintenance of fistula closure if tolerated over the long term.

- Surgery — should be considered early and if long-term maintenance of antibiotics is required.

- AZA/6-MP for maintenance of fistula closure (rates of long-term closure are not high).

Extensive resources available

- Metronidazole.

- Surgery, if an abscess is present (examination under anesthesia and seton insertion).

- Ciprofloxacin.

- A combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. These antibiotics can be used for maintenance of fistula closure if tolerated over the long term.

- Surgery — should be considered early and if long-term maintenance of antibiotics is required, and particularly if the fistula is simple.

- AZA/6-MP for maintenance of fistula closure.

- Infliximab.

- Adalimumab for infliximab failure, or as an alternative to infliximab primarily.

- Surgery for complex fistulas.

8. References

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54.e42; quiz e30.

- Victoria CR, Sassak LY, Nunes HR de C. Incidence and prevalence rates of inflammatory bowel diseases, in midwestern of São Paulo State, Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol 2009;46:20–5.

- Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-Pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology 2013;145:158–65.

- Gearry RB, Richardson A, Frampton CMA, Collett JA, Burt MJ, Chapman BA, et al. High incidence of Crohn’s disease in Canterbury, New Zealand: results of an epidemiologic study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:936–43.

- Wilson J, Hair C, Knight R, Catto-Smith A, Bell S, Kamm M, et al. High incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Australia: a prospective population-based Australian incidence study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:1550–6.

- Asakura K, Nishiwaki Y, Inoue N, Hibi T, Watanabe M, Takebayashi T. Prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2009;44:659–65.

- Sood A, Amre D, Midha V, Sharma S, Sood N, Thara A, et al. Low hygiene and exposure to infections may be associated with increased risk for ulcerative colitis in a North Indian population. Ann Gastroenterol 2014;27:219–23.

- Pugazhendhi S, Sahu MK, Subramanian V, Pulimood A, Ramakrishna BS. Environmental factors associated with Crohn’s disease in India. Indian J Gastroenterol 2011;30:264–9.

- Ng SC, Leung WK, Li MK, Leung CM, Hui YT, Ng CKM, et al. Su1303: Prevalence and disease characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Chinese: results from a nationwide population-based registry [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2015;148(4):S-467.

- Ng SC. Emerging leadership lecture: Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: emergence of a “Western” disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:440–5.

- Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FKL, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1266–80.

- Park SJ, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Clinical characteristics and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison of Eastern and Western perspectives. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:11525–37.

- Brant SR. Promises, delivery, and challenges of inflammatory bowel disease risk gene discovery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:22–6.

- Juyal G, Amre D, Midha V, Sood A, Seidman E, Thelma BK. Evidence of allelic heterogeneity for associations between the NOD2/CARD15 gene and ulcerative colitis among North Indians. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:1325–32.

- Ng SC, Tsoi KKF, Kamm MA, Xia B, Wu J, Chan FKL, et al. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:1164–76.

- Israeli E, Ryan JD, Shafer LA, Bernstein CN. Younger age at diagnosis is associated with panenteric, but not more aggressive, Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:72–9.e1.

- Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:645–59.

- Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM, Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology 2012;143:375–81.e1; quiz e13–4.

- Nguyen GC, Bressler B. A tale of two cohorts: are we overestimating the risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease? Gastroenterology 2012;143:288–90.

- Lin JF, Chen JM, Zuo JH, Yu A, Xiao ZJ, Deng FH, et al. Meta-analysis: fecal calprotectin for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1407–15.

- Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:443–68.

- Ng SC, Hirai HW, Tsoi KKF, Wong SH, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: accuracy of interferon-gamma releasing assay and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease in Asians. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1664–70.

- Wong SH, Ip M, Tang W, Lin Z, Kee C, Hung E, et al. Performance of interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis screening in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:2067–72.

- Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND, Rane PS. Diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in India where tuberculosis is widely prevalent. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:741–6.

- Bae JH, Park SH, Lee H, Lee HJ, Soh JS, Lee S, et al. Su1190: Development of a score for differential diagnosis between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease: a prospective study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2015;148(4):S-432.

- Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, McQuaid KR, Subramanian V, Soetikno R, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:489–501.e26.

- Mohammed N, Kant P, Abid F, Rotimi O, Prasad P, Hamlin JP, et al. 446: High definition white light endoscopy (HDWLE) versus high definition with chromoendoscopy (HDCE) in the detection of dysplasia in long standing ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81(5):AB148.

- Iacucci M, Gasia MF, Urbanski SJ, Parham M, Kaplan G, Panaccione R, et al. 327: A randomized comparison of high definition colonoscopy alone with high definition dye spraying and electronic virtual chromoendoscopy using iSCAN for detection of colonic dysplastic lesions during IBD surveillance colonoscopy [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2015;148(4):S-74.

- Tontini GE, Vecchi M, Neurath MF, Neumann H. Advanced endoscopic imaging techniques in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:261–9.

- Kiesslich R, Neurath MF. Chromoendoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2012;41:291–302.

- Dong J, Wang H, Zhao J, Zhu W, Zhang L, Gong J, et al. Ultrasound as a diagnostic tool in detecting active Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Radiol 2014;24:26–33.

- Wu LM, Xu JR, Gu HY, Hua J, Hu J. Is magnetic resonance imaging a reliable diagnostic tool in the evaluation of active Crohn’s disease in the small bowel? J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:328–38.

- Giles E, Barclay AR, Chippington S, Wilson DC. Systematic review: MRI enterography for assessment of small bowel involvement in paediatric Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:1121–31.

- Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, Escher JC, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:795–806.

- Samaan MA, Mosli MH, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, DʼHaens GR, Dubcenco E, et al. A systematic review of the measurement of endoscopic healing in ulcerative colitis clinical trials: recommendations and implications for future research. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1465–71.

- Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis 2009;3:8–14.

- Mayberry JF, Lobo A, Ford AC, Thomas A. NICE clinical guideline (CG152): the management of Crohn’s disease in adults, children and young people. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:195–203.

- Wedlake L, Slack N, Andreyev HJN, Whelan K. Fiber in the treatment and maintenance of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:576–86.

- Ford AC, Khan KJ, Achkar JP, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of oral vs. topical, or combined oral and topical 5-aminosalicylates, in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:167–76; author reply 177.

- Irving PM, Gearry RB, Sparrow MP, Gibson PR. Review article: appropriate use of corticosteroids in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:313–29.

- Dassopoulos T, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter YT, Inadomi JM, Hanauer SB. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the use of thiopurines, methotrexate, and anti-TNF-α biologic drugs for the induction and maintenance of remission in inflammatory Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2013;145:1464–78.e1–5.

- Gardiner SJ, Gearry RB, Begg EJ, Zhang M, Barclay ML. Thiopurine dose in intermediate and normal metabolizers of thiopurine methyltransferase may differ three-fold. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:654–60; quiz 604.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:459–77.

- Fries W, Cottone M, Cascio A. Systematic review: macrophage activation syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:1033–45.

- Ogata H, Matsui T, Nakamura M, Iida M, Takazoe M, Suzuki Y, et al. A randomised dose finding study of oral tacrolimus (FK506) therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut 2006;55:1255–62.

- Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson AB, Williams CN, et al. Oral budesonide for active Crohn’s disease. Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994;331:836–41.

- Feagan BG, McDonald JWD, Panaccione R, Enns RA, Bernstein CN, Ponich TP, et al. Methotrexate in combination with infliximab is no more effective than infliximab alone in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2014;146:681–8.e1.