Did a Journalist Violate Hacking Law to Leak Fox News Clips? The Government Thinks He Did. (original) (raw)

For days press-freedom advocates have been in an uproar over the recent government raid on a small-town Kansas newspaper’s offices and the homes of its reporters and publisher. The aggressive action is said to have contributed to the death of the Marion County Record’s elderly owner. Following days of public outcry and pressure, the local prosecutor has agreed to withdraw the search warrant and return seized materials to the newspaper and its reporters.

But a similar case has been brewing in Florida for several months that raises the same questions about government searches and seizures of media. It has received much less attention, however, and so far attempts by the journalist in question to get his materials returned has been unsuccessful.

The case involves a freelance journalist and media consultant named Timothy Burke, whose home and office were raided in May after un-aired Fox News video clips he provided to Vice news and another online entity got published last October and in May. Fox News contends the clips were obtained illegally, and prosecutors in Florida seem to agree.

The government says Burke violated the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). But Burke’s lawyers say his only “crime” was embarrassing Tucker Carlson and Fox News, and that the government has wildly misread the CFAA in order to find cause to seize Burke’s work materials — materials that may include additional unpublished videos that could embarrass Fox News.

The story begins last October when Ye, the rapper previously known as Kanye West, sat for an interview with Fox News host Tucker Carlson. Carlson wanted to talk about blowback Ye had received for sporting a sweatshirt with the words “White Lives Matter.”

Carlson introduced the interview, broadcast over two days, by saying many people considered Ye crazy. But after speaking with the rapper himself, Carlson concluded he had “rarely heard a man speak so honestly and movingly about his beliefs.”

The curated interview contained some forthright and lucid comments from Ye — but it also had many rambling, stream-of-consciousness digressions that caught headlines when the interview aired. At one point Ye provocatively claimed that Jared Kushner, son-in-law of former President Donald Trump, only got involved in Middle East peace initiatives to make money. When he paused and asked Carlson if that was "too heavy-handed” to say on Fox News — a media channel known for strongly supporting the Trump family — Carlson replied: “No. That’s your opinion. We’re not in the censorship business.”

What viewers didn’t see, however, were a series of far more provocative statements Ye made during the interview, which Fox News edited out of the broadcast discussion.

Days later, Vice news published a story containing some of those un-aired clips, but didn’t say how it obtained them. The clips included what appeared to be a number of anti-semitic statements Ye made during the discussion; as well as his belief that someone had planted professional actors — “fake children” — in his home to “sexualize” his children; and a claim that Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, launched the non-profit organization in cahoots with the Ku Klux Klan as a secret bid to control “the Jew population.”

Months later, not long after the Fox Corporation fired Carlson, reportedly over crude and highly offensive emails he wrote that the company feared could get them in trouble, Media Matters for America, a left-leaning media watchdog, published more clips from the Tucker Carlson Tonight show — this time depicting crude and offensive behind-the-scenes comments Carlson made to his studio crew (apparently in August 2022) while the camera was rolling.

In the candid footage, he called an attorney for Dominion Voting Systems a “slimy little motherfucker" because the attorney had asked Carlson probing questions during a deposition in the defamation case Dominion brought against Fox. He also denigrated his employer and made sexist and flirtatious remarks to a woman applying his makeup. The Fox Corporation sent Media Matters a cease-and-desist letter on May 5, saying the clips had been illegally obtained and insisted the group take them down.

Media Matters refused.

“Reporting on newsworthy leaked material is a cornerstone of journalism,” Media Matters President Angelo Carusone said in response to Fox’s demand, according to CNN. “For Fox to argue otherwise is absurd and further dispels any pretense that they’re a news operation.“

By then, the FBI had already launched an investigation into the leaks to Vice news, and obtained a warrant to search the Florida home of online journalist Timothy Burke — and his wife, Tampa city councilwoman Lynn Hurtak — who was suspected of leaking the clips. Early on the morning of May 8, days after Media Matters published the Carlson clips, agents raided Burke’s home and a backyard unit he used as an office. They seized about two dozen items, including half a dozen laptops belonging to Burke and Hurtak, thumb and external hard drives, as well as cell phones and several paper notebooks.

Burke hasn’t been charged with any crimes yet, and the government won’t unseal the affidavit it used to obtain the search warrant that would provide the government’s justification for the search. But other public documents filed in the case indicate the government believes Burke violated the CFAA and federal wiretapping laws, without indicating the specific crimes he allegedly committed.

Attorney Mark Rasch, who is on Burke’s defense team, confirmed to Zero Day that the search and seizure was about the leaked Carlson and Ye clips, that he acknowledges Burke leaked to Vice news and Media Matters.

“We don’t actually know what the government thinks he did that was illegal; just that they think he violated the CFAA in some way,” Rasch told Zero Day. He says, however, that Burke committed no crimes, and didn’t hack anything to obtain the clips. They were publicly accessible and unencrypted.

The raid raises issues about the First Amendment and journalist rights, as well as charges of government overreach. Rasch says the government seized Burke’s entire newsroom — the equipment he uses to conduct research, plus 100 terabytes of recorded video streams and other data that make up his work product, in addition to materials that would identify his sources. The tens of thousands of hours of video footage Burke has downloaded and archived from Fox News and other broadcasters over years contain newsworthy content that Burke and other journalists have either already reported on or intend to report on in the future, he says.

Since May, Burke’s attorneys have been pressing prosecutors to return their client’s materials — which potentially include additional un-aired and embarrassing clips Fox News and others would not want anyone to see — saying the seizure amounts to prior restraint of Burke’s free speech as well as interference with his First Amendment-protected news-gathering and reporting activities.

They accuse the government of violating the Privacy Protection Act, which generally prohibits prosecutors from seeking a warrant for the “work product materials” of journalists. The statute defines a journalist as someone who gathers information for the purpose of disseminating it to the public in a newspaper, book, broadcast, or other form of public communication. There are exceptions that allow the government to search and seize journalist materials if the materials are connected to a crime the government believes the journalist has committed. And in this case, prosecutors say Burke violated the CFAA, thereby forfeiting his journalistic protections — though they haven’t told Burke’s defense attorneys the nature of the crime and are refusing to show them the FBI affidavit prosecutors used to obtain the search warrant, which would detail those crimes.

Rasch believes Florida prosecutors have misread the statute and are using a “novel and unsupported” interpretation of it to assert a crime that doesn’t exist under the law — Rasch, a former federal prosecutor is in a unique position to understand the statute’s intent, since he helped craft it when he worked for the government.

He and the defense team have filed a motion to unseal the affidavit to determine what crime agents allege Burke committed and whether prosecutors disclosed to the court that Burke is a journalist and followed proper procedures required for investigating members of the media.

The government can obtain a warrant to search journalists suspected of committing crimes in the course of their work, but per the Justice Department’s own policies, it requires approval from the attorney general or deputy assistant attorney general for the criminal division. And it also requires appointing a “special master” or independent “taint team” to prevent investigators from viewing and collecting privileged material unrelated to the alleged crime during their search.

The government has insisted, in its response to the motion, that an agent on the search team did act as a filter to weed out potentially privileged material from evidence related to the alleged crimes, and that investigators followed additional protocols to protect Burke’s work materials. But it opposes unsealing the affidavit because it says this would damage the ongoing investigation. The court has yet to rule on the matter.

Rasch believes Florida prosecutors have misread the statute and are using a “novel and unsupported” interpretation of it to assert a crime that doesn’t exist under the law — Rasch, a former federal prosecutor is in a unique position to understand the statute’s intent, since he helped craft it when he worked for the government.

Prosecutors did agree to one defense request — to provide Burke with copies of the portions of seized hard drives that contain no data related to the alleged crimes so that he can continue with his work. But to do this, Burke would have to tell them which of the seized files are “privileged” work material — which would mean identifying sources and materials provided by those sources that are published and not yet published, which could potentially compromise his work and those sources.

Oddly, while the government insists it followed proper protections for Burke’s work materials, at the same time it appears to dispute Burke’s status as a journalist in court documents, suggesting he has no right to the protections afforded to journalists.

Is Burke a Journalist?

The government didn’t respond to an inquiry, but in court documents they don’t dispute that Burke was at one time a journalist. They suggest, however, that this is no longer the case and that he has since become a political consultant — running the campaign to help his wife win her city council election — and advisor to media organizations.

Burke began his journalism career in an unconventional way. In a Netflix documentary aired last year, he described traveling in “interesting online circles” during his early years, including with the notorious hacker collective known as Anonymous. Working with that group, he says he developed special research skills that gave him a reputation as “someone who finds things.”

Between 2011 and 2019, Burke put those skills to good use, working as a reporter for Deadspin (then part of the Gizmodo Media Group) and the Daily Beast, both as an independent researcher and a staff reporter and video director.

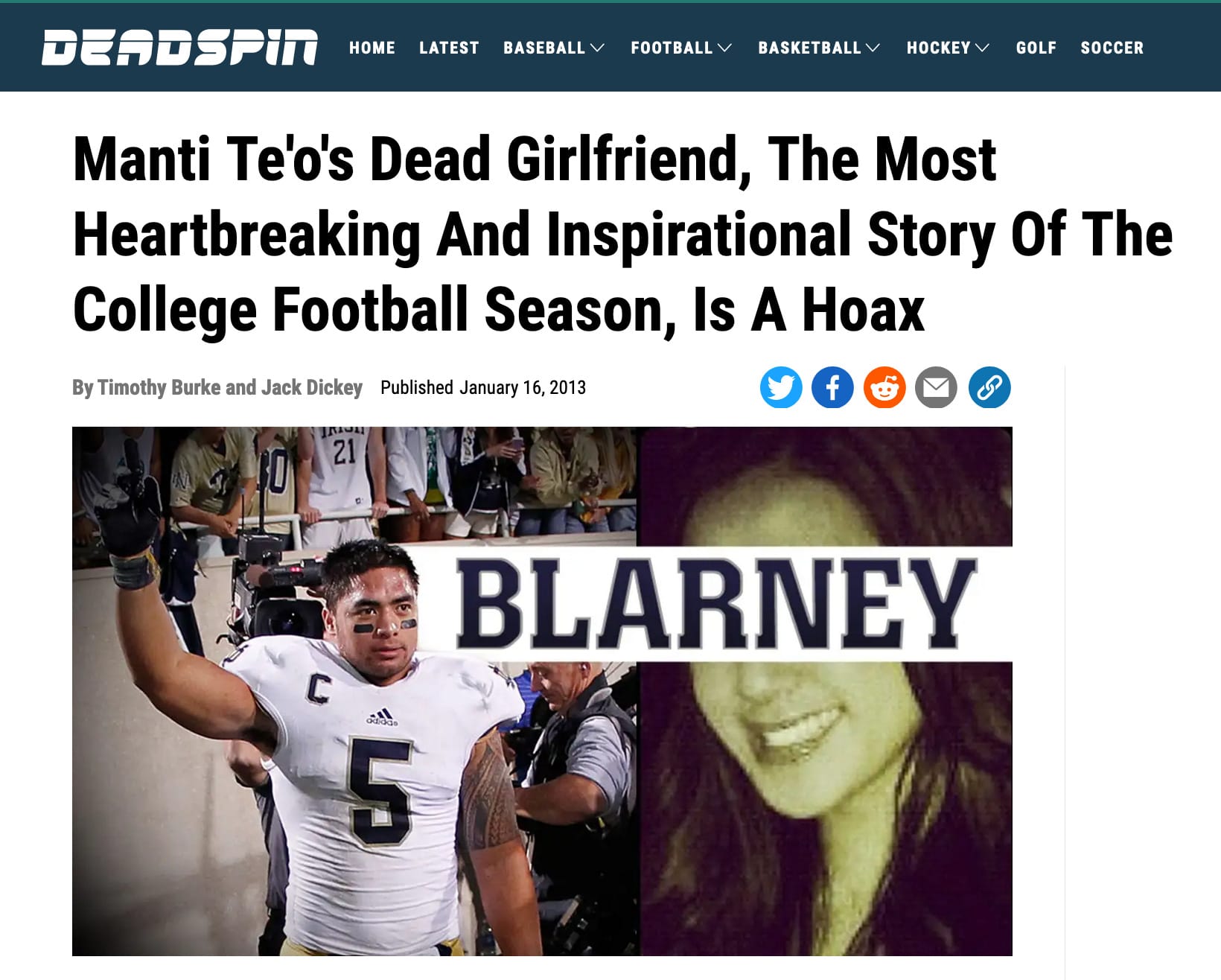

In 2013, he and a colleague at Deadspin produced an explosive report exposing a person who allegedly “catfished” NFL linebacker Manti Te’o by tricking him into getting into a fake online relationship with a woman who didn’t exist. The work was a finalist for a journalism award and led to a Netflix documentary about his investigative methods. In 2018 after CNN reported that local news anchors for Sinclair Broadcasting affiliates around the country had been caught reading an identical script bashing other media outlets, Burke pieced together and published video evidence from dozens of clips confirming the CNN reporting.

Between 2018 and 2019, Burke worked for the Daily Beast as director of video journalism, and after this he launched Burke Communications, described as a consulting, political strategy and social media training company. His lawyers say this has included freelance journalism work, some of it published by himself and some done as contracted research work for news organizations and other reporters. This primarily involves researching and uncovering salient video clips from a vast archive of video feeds he has collected over the years.

A 2013 New York Times profile of Burke described some of his methods for uncovering hard-to-find video and information. It described a ten-monitor set up in his office that let him track twenty-eight broadcasts simultaneously. The setup has since morphed into about three dozen monitors, according to his web site, that allow him to record thousands of hours of live streams weekly to amass a “181,000-gigabyte video archive.” This includes local news broadcasts during the George Floyd protests and footage of last year’s Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Earlier this year, after veteran Oakland A’s announcer Glen Kuiper apologized for something he’d said on air without going into detail, Burke published the clip that showed Kuiper using the “n-word” in talking about a visit to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Kuiper claimed he’d simply mispronounced the name of the museum, but he was fired.

The government, however, says Burke’s journalism days are behind him because it can’t find any work under his byline since January 2021. Prosecutors cite his web site, which describes him as a political and communications consultant, a broadcast monitor, archival technologist, media trainer and viral content visionary, but not a journalist.

But Andrew Crocker, surveillance litigation director for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, says a journalist is defined by what they do not their title or where they work.

“If someone is collecting information as part of a process to then disseminate newsworthy information to the public, that’s a journalist. If that’s what he was doing, then he’s a journalist,” Crocker says.

The question then is, did he lose his journalism protection by committing crimes, as the government asserts.

Accessing the Clips

Burke and his attorneys don’t dispute that he provided the Fox News clips to Vice and Media Matters. During an interview with Zero Day, Burke said he can’t recall many of the details around how or when he obtained access to the videos, and because the government hasn’t returned his seized materials, he’s unable to review them to provide a timeline.

But piecing together comments from Rasch and the defense team’s motion to unseal the affidavit, an account of how he obtained the clips emerges.

Some time last year, likely in August, someone who previously provided news tips to Burke found the username and password for a demo account on a web site used by broadcasters, Rasch says. The site, LiveU.tv, provides transmission services to TV and radio broadcasters and others so they can send live feeds from the field to production offices and affiliates over the internet, instead of via satellite as the industry would have done in the past.

Burke’s tipster found the credentials for the LiveU.tv demo account on a web page belonging to a CBS radio affiliate in Tennessee. Rasch says the credentials were on a page that had been archived by the Internet Archive — a site that takes regular snapshots of web sites to preserve their contents for posterity.

It’s not clear why the radio station published the credentials. Rasch says it’s common for online services to provide demo accounts for prospective customers to view their services before subscribing, and it’s likely that the radio station didn’t consider the credentials to be sensitive since, he says, people often share demo credentials. Rasch and Burke couldn’t recall the name of the radio station, so Zero Day couldn’t confirm their account of what occurred. LiveU.tv also did not respond to inquiries, but its published terms of service do not prohibit the sharing of account credentials — demo or otherwise.

Neither Rasch nor Burke could say when the credentials were published or when the tipster found them. Burke also could not recall when he used them to log into LiveU.tv's web site or how many times he used them. But the government cites August 2022 as the time frame the alleged criminal activities began — which appears to be the same month Carlson made the comments about Dominion’s lawyer and two months before Carlson’s interview with Ye aired.

According to Rasch, once Burke accessed the LiveU.tv site, the site pushed a text file to his browser cache, which contained URLs for all of the video feeds the site was hosting at the time. This included a URL for Fox News and Tucker Carlson’s show.

By copy-pasting the URL into his browser window, Burke could view the live feed for Fox News, which wasn’t encrypted (he notes that when video feeds are encrypted a token indicating such is in the URL ). He recorded the unencrypted feed, and after the interview with Ye was broadcast, he reviewed the entire original and uncovered parts that Fox News had left out.

Rasch and Burke say that all of the URLs that were in the .txt file LiveU.tv pushed to his browser were publicly accessible addresses, and the content found at those addresses was not password-protected, meaning that although Burke obtained the URLs after logging into the LiveU.tv web site, anyone who knew the URLs would have been able to go directly to the same live feeds without using the demo credentials to log into LiveU.tv’s site. Rasch says the URLs for each broadcaster’s live feeds contained sequential numbers, so that by knowing the URL for one of the broadcaster’s live feeds, someone could alter the number and pull up a different unencrypted live feed for the same broadcaster.

It’s not clear what action Burke took constitutes a crime in the minds of prosecutors — whether they think he broke the law by using the publicly accessible demo credentials, or by viewing and recording the unencrypted live feeds, or both.

If the government alleges that Burke violated the CFAA by using the credentials then, Rasch says, this would criminalize the sharing of any password. Family members who share Netflix passwords would be violating the CFAA, he says, and this is not what the statute intended or says.

The government may, however, say that Burke violated the portion of the CFAA that pertains to “unauthorized access” — that is, even though the feeds were unencrypted and were publicly accessible without needing to use a password, Burke should have known that Fox News did not intend for him to access and record them, and his actions therefore were unauthorized.

But Rasch says “unauthorized access” under the CFAA doesn’t mean access is criminal simply if the owner didn’t intend or want someone to gain access to something.

“The government is taking the position that accessing without authorization is accessing without express authorization, which would be incredibly dangerous because you have no way of knowing what the owner intends [if information is public],” he says. “Let’s say you type in a random URL and it resolves to something. Is the onus on you to determine that it should not have been public?”

Burke, he says, engaged in “acts and works of journalism” on the open internet, in the same way journalists and open-source researchers investigate stories all the time. And to read the criminal hacking statute in a way that would require journalists to obtain express authorization to access and publish something would prohibit many forms of journalism, he notes, since investigative journalism is all about finding and reporting information that people, including powerful entities, don’t want disclosed.

“It is wholly unreasonable to expect a journalist who finds information or streaming content on a publicly accessible website to assume that the person or persons who put the content out there in the public domain ‘did not know’ or ‘did not want’ that content to be publicly accessible,” he wrote in the motion to unseal the affidavit.

EFF’s Crocker agrees. He cites the case of First Amendment advocates in Fullerton, California, who found a misconfigured “drop-box” the city used to post documents that were responsive to public records requests. The dropbox allowed access to a file storing raw documents before the city reviewed and redacted them for distribution to the public. The activists found the documents and published them. The city accused them of hacking its website, and prosecutors said they should have known the records weren’t intended for the public. But a court ruled against them.

“It seems pretty clear based on the text of the CFAA and subsequent court rulings, that merely accessing a publicly accessible web site is not access without authorization under the CFAA,” Crocker says. Courts have made a distinction between information that is publicly available and information that is gated to prevent access.

“If there is nothing stopping you, if it’s a publicly accessible web site, then it’s not a violation of the CFAA,” per the courts, he says.

He also says that if the LiveU.tv credentials Burke used were truly for a demo account that was meant to be used by the public, “that would be a very bad argument that this would be a violation of the CFAA” as well.

If these acts don’t violate the CFAA, then it would appear that the government had no legal justification to obtain the search warrant, Rasch says. And like the prosecutor in Kansas who recently revoked the warrant in that case and returned seized materials to the journalists of the Marion County Record, he says Florida prosecutors should return all of Burke’s seized materials.

Thank you for reading. If you found this article useful or interesting, feel free to share it with others.

Zero Day is a reader-supported publication. You can support my work by becoming a paid subscriber; or if you prefer, you can subscribe for free:

You can also give a gift subscription to someone else: