The life of Richard Henry Green (original) (raw)

Yale College’s first African American graduate became a Civil War assistant surgeon and a New England country doctor.

Manuscripts and Archives

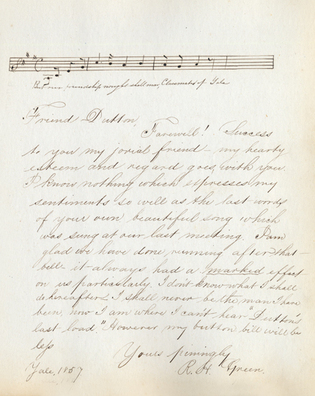

In the era when Green graduated, seniors signed each other's Yale albums. Some of Green's classmates' albums are now in the Manuscripts and Archives department of Sterling Memorial Library, and several of them bear his signature. To one classmate, Henry M. Dutton, he wrote a lengthy farewell notes.View full image

Recent news about the auction—and acquisition by Yale Manuscripts and Archives—of a collection of the papers of Richard Henry Green, Class of 1857, has led to the discovery of a lost milestone in Yale history. For nearly 150 years, his racial identity had been overlooked.

Through the growing accessibility of digitized documentation, it is now known that in June 1874, the local newspapers that reported on the graduation of Edward Bouchet ’74, ’76PhD, an African American, also referenced his predecessors at Yale: Courtlandt Van Rensselaer Creed ’57MD, one paper explained, had entered medical school in the mid-1850s, and “about that time another light mulatto entered the academical department and graduated in due time.” This second man was Green, who had entered the year before Creed. The following brief note was published in the American Educational Annual, 1875: “Five colored men have been graduated from the different schools of Yale. The first was Richard Henry Green of the class of 1857, who became a physician, graduating in the Medical School at Dartmouth.” (The fourth man was James William Morris ’74BD, who attended the Divinity School; the fifth man is unknown.)

Green entered Yale in the fall of 1853. His father was Richard Green, a bootmaker who worked and lived with his family near the corner of State and Chapel Streets, four blocks from the Yale campus. The elder Green was also a founder and treasurer of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, an African American place of worship then located on Park Street near the campus. He had come to New Haven from Wilmington, North Carolina, where he had been employed for some years in a boot- and shoemaking business owned by Charles and George Bradley of New Haven. In 1833, the Bradleys engaged him to come to New Haven, where they had established a new operation. Ten years later, Green and a close friend and coworker from North Carolina founded their own bootmaking company, Wright & Green, and over four decades “made boots for numbers of prominent men,” the New Haven Evening Register recorded in an 1878 article on the business.

In 1850 there were 989 African Americans in New Haven, 4.8 percent of the population. It was the highest African American percentage of any city in the Northeast, twice that of New York and three times more than Boston. Other African Americans besides Richard Green Sr. were running their own businesses; Courtlandt Van Rensselaer Creed’s father, John, was a steward at Yale, a college janitor, an ice cream manufacturer, and caterer of the commencement dinners for Yale alumni for four decades. Creed’s mother, Vashti Duplex Creed, was the first African American teacher in New Haven.

It’s possible, though far from certain, that the younger Richard Green lived as a white man after he moved away from New Haven, as both he and his wife were listed in the 1870 federal census as white. But in New Haven and at Yale, with a father of some prominence in the community, Green likely identified as and was known as black. In the New Haven City Directory, published regularly beginning in 1840, the elder Green was regularly listed as “col’d” over four decades (except for the years 1841–44 and 1853–54). His son was listed separately beginning in 1853–54; he was not listed as colored. But the federal census recorded him in 1850 as a 17-year-old clerk, mulatto; and in 1860, when he was still living in New Haven, as a 26-year-old teacher, black. As for Yale’s own records, they did not specify race in that era, and no mention at the university of Green’s race has been found.

We don’t know how Green came to enter Yale, but Creed’s experience suggests it might not have been easy. On August 6, 1855, Creed wrote to Frederick Douglass to thank Douglass for inspiring him, and he described his strategy for winning a place in the medical school. After meeting Douglass in 1852, he wrote,

I instantly made arrangements for prosecuting the study of medicine. I had my fears and doubts as to whether I would be admitted at “Yale.” Knowing that prejudice against color was somewhat apparent, in time past, I, however, felt nerved for a trial.… Accordingly, I entered the office of George E. Budington, MD [Yale MD 1848], of this city, a distinguished surgeon, physician and scholar, December 18th, 1853, as an “office student,” applying myself closely to my studies. I was not long in unraveling the delicate network which surrounds the study of medicine. By degrees, the doctor generally would send me to look after his patients, until at last he seldom operated without my assistance or presence. On the 14th day of last September, I applied and was admitted into the “medical class” of the “Yale Medical University.”… Both in college and out of its walls, the truth compels me to say, that I never experienced any other than the most polite treatment from my fellow class-mates.

Green’s entry in the student register states that he matriculated on July 18, 1854, at the age of 20, that he came from New Haven, and that his preparatory instructor had been Lucius Wooster Fitch ’40. Fitch, a son of the Yale College pastor, worked for Yale and owned a bookstore; he would have taught Green the Latin, Greek, and mathematics required for admission. Green’s signature in the register is in the perfect copperplate hand he would have employed in his work as a clerk.

There is only one entry on Green in the faculty minutes book. Dated July 20, 1855, it reads: “R. H. Green (Soph) having increased his marks to 48—Voted that indulgence be shown him because he rooms at a distance from college.” “Marks” were given for tardiness and absence from college exercises, chapel, and so forth, and for taking part in disturbances—two to eight marks per incident. When a student went above the limit of 48 marks, he was to be suspended for six weeks or a term. The rule was not strictly enforced, however, and the faculty seem to have excused Green. The college chapel bell began to toll at 5:30 a.m. every day, and the required daily prayer service began at six, followed by a class recitation. Breakfast was served at 7:30. Green had to make his way in darkness much of the year from the African American neighborhood near the railroad, known as “Negro Lane,” where he lived with his family.

It is impossible to know how much Green wished to participate in Yale undergraduate society, or how freely other undergraduates welcomed him. But we do know that he was a member of both the literary society Brothers in Unity and the Sigma Delta fraternity. Some evidence also exists in the senior class books—elegant, leather-bound albums of engravings of college views and faculty, as well as of the graduating seniors. Most students had engravings of themselves made for these albums; Green and a few other classmates did not. The students signed each other’s books, and Green has autographed several of the Class of 1857 albums that have been donated to the Yale archives over the years. Some inscriptions are brief: “Your friend & classmate, R. H. Green Yale 1857.” In some he has written a sentence or two of regards.

One long farewell message to his classmate Henry M. Dutton, of New Haven, attests to their close friendship. (Dutton’s father, Henry Dutton ’18, was a professor in the Yale Law School and, in 1854, governor of Connecticut.) Above the message—which is reproduced on the previous page—Green drew a line of music, with the lyrics “But our friendship nought shall mar, Classmates of Yale.” He continued:

Friend Dutton,

Farewell! Success be yours my jovial friend—my hearty esteem and regard goes, with you. I know nothing which expresses my sentiments so well as the last words of your own beautiful song which was sung at our last meeting. I am glad we have done running after that bell—it always had a marked effect on us particularly. I don’t know what I shall do hereafter. I shall never be the man I have been, now I am where I can’t hear “Dutton’s last load.” However my button bill will be less.

Yours piningly

R. H. Green

Yale, 1857

One of the letters in the Green family papers shows that Green and another Yale student from New Haven remained friends for at least a short while after college. Louis Peck Morehouse ’56S, a student in the Scientific School, was the son of a local sign painter. He wrote to Green in November 1857: “How dull it must be in New Haven! Smith, Austin, Brooks and myself all emigrated!… Farewell, King Richard!”

After graduating, Green taught school—first in Milford, Connecticut, and after a year and a half at the Bennington Seminary in Bennington, Vermont. He then studied medicine at Dartmouth, where he received an MD in 1864. But before that, he entered the US Navy in November 1863 as an acting assistant surgeon. A transcription of his application to the Navy includes a descriptive note from the board that examined him: “Fresh from school; no practical experience—sprightly and tolerably well booked. Weighs 220 lbs.”

His father described his war service in a letter to Franklin B. Dexter ’61, the secretary of the university, which is now preserved in the university archives. His son, he wrote,

was sent to the U.S. Steamer State of Georgia blockading off N. Carolina under Admiral Porter. He was on that vessel about a Year, when she was taken out of commission, and he was put on waiting order 3 weeks. During that time he was married to Miss Charlotte Caldwell of Bennington, VT. Then he was ordered to the Steamer Seneca and was at the taking of Fort Fisher, & the other fortifications in the Cape Fear river.

After the war, the young family settled in Hoosick, in upstate New York. There Green apparently changed the spelling of his surname to Greene; even his father addressed a letter to his son under that name, while keeping “Green” for himself. The younger Green practiced medicine in Hoosick, apparently with success. He preserved a letter from a grateful Connecticut patient who wrote him, “I felt a confidence in you which I do not entertain towards any physician near us.”

It was in Hoosick that Richard and Charlotte Green and their daughter were listed as “white” on the US census. It is important to note, however, that the census does not tell us how Green or his family presented their own race; census workers might well have assigned the labels themselves. And Green may have been away from home when the census worker arrived.

On March 23, 1877, as the elder Green wrote in his letter to Yale’s secretary, his son “died of disease of the heart leaving a wife & daughter.” Richard Henry Green is buried in Bennington, just over the border from Hoosick. An 1897 book, Landmarks of Rensselaer County, would remember the doctor as a man who was “fond of the study of natural history and spent much time collecting plants and objects of interest in that department. He was a most amiable and genial man, and a practical Christian.”