Peptic ulcer: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (original) (raw)

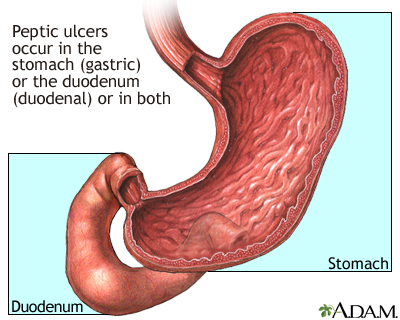

A peptic ulcer is an open sore or raw area in the lining of the stomach or intestine.

There are two types of peptic ulcers:

- Gastric ulcer -- occurs in the stomach

- Duodenal ulcer -- occurs in the first part of the small intestine

Normally, the lining of the stomach and small intestines can protect itself against strong stomach acids. But if the lining breaks down, the result may be:

- Swollen and inflamed tissue (gastritis)

- An ulcer

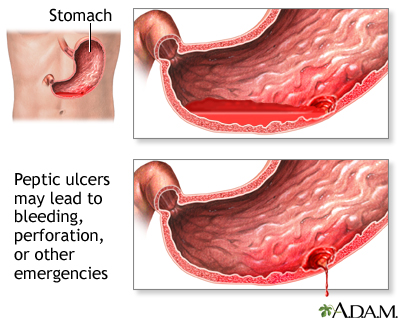

Most ulcers occur in the first, inner surface, layer of the inner lining. A hole in the stomach or duodenum is called a perforation. This is a medical emergency.

The most common cause of ulcers is infection of the stomach by bacteria called Helicobacter pylori (H pylori). Most people with peptic ulcers have these bacteria living in their digestive tract. Yet, many people who have these bacteria in their stomach do not develop an ulcer.

The following factors raise your risk for peptic ulcers:

- Drinking too much alcohol

- Regular use of aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Smoking cigarettes or chewing tobacco

- Being very ill, such as being on a breathing machine

- Radiation treatments

- Stress

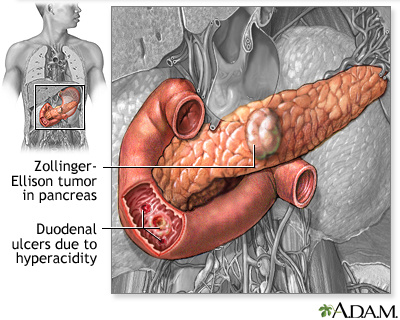

A rare condition, called Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, causes the stomach to produce too much acid, leading to stomach and duodenal ulcers.

Small ulcers may not cause any symptoms and may heal without treatment. Some ulcers can cause serious bleeding.

Abdominal pain (often in the upper mid-abdomen) is a common symptom. The pain can differ from person to person. Some people have no pain.

Pain occurs:

- In the upper abdomen

- At night and wakes you up

- When you feel an empty stomach, often 1 to 3 hours after a meal

Other symptoms include:

- Feeling of fullness and problems drinking as much fluid as usual

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Bloody or dark, tarry stools

- Chest pain

- Fatigue

- Vomiting, possibly bloody

- Weight loss

- Ongoing heartburn

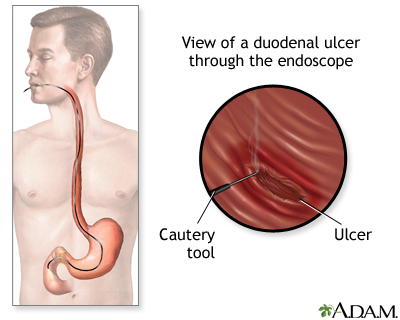

To detect an ulcer, you may need a test called an upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD).

- This is a test to check the lining of the esophagus (food pipe), stomach, and first part of the small intestine.

- It is done with a small camera (flexible endoscope) that is inserted down the throat.

- This test most often requires sedation given through a vein.

- In some cases, a smaller endoscope may be used that is passed into the stomach through the nose. This does not require sedation.

EGD is done on most people when peptic ulcers are suspected or when you have:

- Low blood count (anemia)

- Trouble swallowing

- Bloody vomit

- Bloody or dark and tarry-looking stools

- Lost weight without trying

- Other findings that raise a concern for cancer in the stomach

Testing for H pylori is also needed. This may be done by biopsy of the stomach during endoscopy, with a stool test, or by a urea breath test.

Other tests you may have include:

- Hemoglobin blood test to check for anemia

- Stool occult blood test to test for blood in your stool

Sometimes, you may need a test called an upper GI series. A series of x-rays are taken after you drink a thick substance that contains barium. This does not require sedation.

Your health care provider will recommend medicines to heal your ulcer and prevent a relapse. The medicines will:

- Kill the H pylori bacteria, if present.

- Reduce acid levels in the stomach. These include H2 blockers such as ranitidine (Zantac), or a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) such as omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), esomeprazole (Nexium), rabeprazole (AcipHex) or pantoprazole (Protonix).

Take all of your medicines as you have been told. Other changes in your lifestyle can also help.

If you have a peptic ulcer with an H pylori infection, the standard treatment uses different combinations of the following medicines for 7 to 14 days:

- Two different antibiotics to kill H pylori.

- PPIs such as omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), or esomeprazole (Nexium).

- Bismuth subsalicylate (the main ingredient in Pepto-Bismol) may be added to help kill the bacteria.

You will likely need to take a PPI for 8 weeks if:

- You have an ulcer without an H pylori infection.

- Your ulcer is caused by taking aspirin or NSAIDs.

Your provider may also prescribe this type of medicine regularly if you continue taking aspirin or NSAIDs for other health conditions.

Other medicines used for ulcers are:

- Misoprostol, a medicine that may help prevent ulcers in people who take NSAIDs on a regular basis

- Medicines that protect the tissue lining, such as sucralfate

If a peptic ulcer bleeds a lot, an EGD may be needed to stop the bleeding. Methods used to stop the bleeding include:

- Injecting medicine in the ulcer

- Applying metal clips or heat therapy to the ulcer

Surgery may be needed if:

- Bleeding cannot be stopped with an EGD

- The ulcer has caused a tear in the stomach or duodenum

Peptic ulcers tend to come back if untreated. There is a good chance that the H pylori infection will be cured if you take your medicines and follow your provider's advice. You will be much less likely to get another ulcer.

Complications may include:

- Severe blood loss

- Scarring from an ulcer that may make it harder for the stomach to empty

- Perforation or hole of the stomach and intestines

Get medical help right away if you:

- Develop sudden, sharp abdominal pain

- Have a rigid, hard abdomen that is tender to touch

- Have symptoms of shock, such as fainting, excessive sweating, or confusion

- Vomit blood or have blood in your stool (especially if it is maroon or dark, tarry black)

Contact your provider if:

- You feel dizzy or lightheaded.

- You have ulcer symptoms.

Avoid aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, and other NSAIDs. Try acetaminophen instead. If you must take such medicines, talk to your provider first. Your provider may:

- Test you for H pylori before you take these medicines

- Ask you to take PPIs or an H2 acid blocker

- Prescribe a medicine called misoprostol

The following lifestyle changes may help prevent peptic ulcers:

- DO NOT smoke or chew tobacco.

- Avoid alcohol.

Ulcer - peptic; Ulcer - duodenal; Ulcer - gastric; Duodenal ulcer; Gastric ulcer; Dyspepsia - ulcers; Bleeding ulcer; Gastrointestinal bleeding - peptic ulcer; Gastrointestinal hemorrhage - peptic ulcer; G.I. bleed - peptic ulcer; H. pylori - peptic ulcer; Helicobacter pylori - peptic ulcer

Chan FKL, Lau JYW. Peptic ulcer disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 53.

Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and other gastric Helicobacter species. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 217.

Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390(10094):613-624. PMID: 28242110 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28242110/.

Updated by: Michael M. Phillips, MD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.