Rajani Palme Dutt (original) (raw)

Rajani Palme Dutt, the son of an Indian doctor and a Swedish mother, was born on 19th June, 1896. Dutt was brought up in Cambridge and educated at The Perse School before winning a place at Balliol College, Oxford.

Dutt was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Due to heavy losses at the Western Front the government decided in 1916 to introduce conscription (compulsory enrollment).

As a pacifist Dutt refused to serve in the armed forces. However, he was told conscription "did not apply to him, on racial grounds". He appealed successfully and when he was conscripted he refused to serve and was sentenced to six months in prison. Soon after his release he was expelled from Oxford University for organizing a meeting in support of the Russian Revolution. He was allowed back to take his finals and won a first-class degree, the best of his year.

In 1919 he was made international secretary of the Labour Research Department. A large number of socialists had been impressed with the achievements of the Bolsheviks following the Russian Revolution and in April 1920 several political activists, including Tom Bell, Willie Gallacher, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Helen Crawfurd and Willie Paul to establish the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. Rajani Palme Dutt was one of the first people to join the CPGB.

In 1921 Dutt founded the magazine The Labour Monthly, which he edited for over 50 years. Dutt, along with Harry Pollitt and Hubert Inkpin was charged with the task of implementing the organisational theses of the Comintern. As Jim Higgins has pointed out: "In the streamlined “bolshevised” party that came out of the re-organisation, all three signatories reaped the reward of their work. Inkpin was elected chairman of the Central Control Commission Dutt and Pollitt were elected to the party executive. Thus started the long and close association between Dutt and Pollitt. Palme Dutt, the cool intellectual with a facility for theoretical exposition, with friends in the Kremlin and Pollitt the talented mass agitator and organiser."

Dutt was also a member of Comintern and was given the task of supervising the Communist Party of India. His wife, Salme Murrik was also a member of the CPGB. In 1936 he replaced Idris Cox as editor of the Daily Worker.

Dutt was a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky in the Soviet Union. In the Daily Worker on 12th March, 1936, Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the CPGB, argued that the proposed trial of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin represented "a new triumph in the history of progress". Later that year all sixteen men were found guilty and executed.

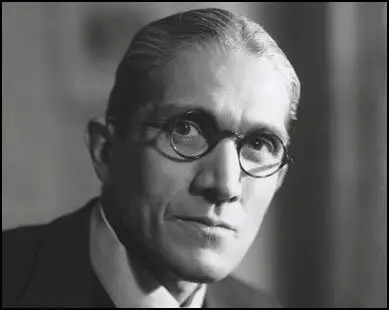

Rajani Palme Dutt

Dutt used the The Labour Monthly and the _Daily Worker_to defend the Great Purge. As Duncan Hallas pointed out: "He repeated every vile slander against Trotsky and his followers and against the old Bolsheviks murdered by Stalin through the 1930s, praising the obscene parodies of trials that condemned them as Soviet justice".

Harry Pollitt remained loyal to Joseph Stalin until September 1939 when he welcomed the British declaration of war on Nazi Germany. Stalin was furious with Pollitt's statement as the previous month he had signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact with Adolf Hitler.

At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." Bob Stewart disagreed and mocked "these sledgehammer demands for whole-hearted convictions and solid and hardened, tempered Bolshevism and all this bloody kind of stuff."

William Gallacher agreed with Stewart: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades." Harry Pollitt joined in the attack: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten."

John R. Campbell, the editor of the Daily Worker, thought the Comintern was placing the CPGB in an absurd position. "We started by saying we had an interest in the defeat of the Nazis, we must now recognise that our prime interest in the defeat of France and Great Britain... We have to eat everything we have said."

Harry Pollitt then made a passionate speech about his unwillingness to change his views on the invasion of Poland: "I believe in the long run it will do this Party very great harm... I don't envy the comrades who can so lightly in the space of a week... go from one political conviction to another... I am ashamed of the lack of feeling, the lack of response that this struggle of the Polish people has aroused in our leadership."

However, when the vote was taken, only Harry Pollitt, John R. Campbell and William Gallacher voted against. Pollitt was forced to resign as General Secretary and he was replaced by Dutt and William Rust took over Campbell's job as editor of the Daily Worker. Over the next few weeks the newspaper demanded that Neville Chamberlain respond to Hitler's peace overtures.

On 22nd June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union. That night Winston Churchill said: "We shall give whatever help we can to Russia." The CPGB immediately announced full support for the war and brought back Harry Pollitt as general secretary. Membership increased dramatically from 15,570 in 1938 to 56,000 in 1942.

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive".

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprisingan estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

Over 7,000 members of the Communist Party of Great Britain resigned over what happened in Hungary. Harry Pollitt responded by resigning as General Secretary of the CPGB. However, Rajani Palme Dutt continued to remain loyal to the Soviet Union and in 1968 disagreed with the the CPGB opposition to the Warsaw Pact intervention in Czechoslovakia.

Rajani Palme Dutt died on 20th December 1974.

Primary Sources

(1) Rajani Palme Dutt, The Communist (18th November, 1920)

It is now two years since open warfare in Western Europe ceased. For two years the rulers of the Entente have been free to mould the world to their will. We may now survey, their handiwork.

What was the position when they began? Ten million men had been killed. Areas lay devastated. Industry and production had been diverted for four years to the work of destruction. Shortage and underfeeding and disease were sapping the populations of whole countries.

In so desperate a situation it would have seemed plain common sense to set production going as fast as possible to supply the world’s needs.

But to talk of common sense is to forget capitalism. The object of capitalism is not to supply the goods that are needed but to make a profit. If a bigger profit can be made by smashing rivals and creating shortage, then that profit will be made, and capitalism is blind to the consequence.

The moment of power was with the rulers of the Entente. The rulers of the Entente used their moment of power to smash their rivals and create word shortage.

(2) Rajani Palme Dutt, The Communist International (June, 1926)

The British and international bourgeoisie are singing their song of triumph over the defeat of the British general strike. It is a song that will be short-lived. The British general strike is not only the greatest revolutionary advance in Britain since the days of Chartism, and the sure prelude of the new revolutionary era, but its very defeat is a profound revolutionary lesson and stimulus. Gigantic tasks await the working-class vanguard in Britain: but henceforth the old conditions can no longer continue; the old British social fabric of parliamentary and democratic hypocrisy has received shattering blows; and the British working class has entered into a new era, the era of mass struggle, which can only culminate in open revolutionary struggle. By their methods of suppressing the general strike, by their open dictatorship and display of armed force, by their ruthless prosecution of the struggle on the basis of war, by their transference at last of the methods of armed force from the colonies into Britain itself, the British bourgeoisie has taught the proletariat a lesson of inestimable revolutionary value. The defeat of the general strike is itself a gigantic piece of revolutionary propaganda.

Not the masses were defeated, but the old leadership, the old reformist trade unionism, parliamentarism, pacifism and democracy. The masses stood solid: these broke down; these were the real casualties of the fight; and the masses will learn to fling them aside when it comes to the future struggle. The driving home of this lesson, the shattering of the old traditions and leadership, the tireless preparation for the future struggle, and above all the building up of an iron revolutionary vanguard of the workers and kernel of new leadership - these are the tasks that follow or the collapse of the general strike.

The general strike has brought the British working class face to face with the political issue of power, with the legal and armed force of the State. The old trade union tradition has been brought to its highest culminating point, only to have its complete impotence shown unless it can pass into this higher plane. The masses have entered into the full highway of mass struggle, and shown a solidarity, courage, tenacity and class-will, which affords the guarantee of future revolutionary victory. This time they entered the struggle with the old traditions, apparatus, leadership, all fundamentally opposed to the struggle, and only dragged along with them by the force of their mass-will; their limbs were shackled by the myriad trade union-economic-pacifist-legalist-constitutional-democratic traditions; and under these conditions defeat in the first shock was inevitable. But the positive lessons of the struggle are stronger than all the treacheries of the reformist leadership. The class-character of the State has been exposed. The trappings of parliament, democracy, trade union legalism and economism have been torn aside, and laid bare the naked class-power opposition with its ultimate weapon of armed force. The future struggle in Britain can henceforth only be the revolutionary mass struggle with an open political aim. The bourgeoisie have themselves shown the way forward to the proletariat.

The first British general strike is so decisive a turning point in British history, its whole process so complete a picture of the existing stage of the Working-Class Movement, and the lessons to be drawn from it on fuller analysis so infinite and varied, that at the present moment in a pamphlet written immediately after the calling off of the general strike, it is only possible to deal with a few of the simplest and plainest issues.

(3) Rajani Palme Dutt, The Labour Monthly (April, 1953)

The genius and will of Stalin, the architect of the rising world of free humanity, lives on for ever in the imperishable monument of his creation - the soaring triumphs of socialist and communist construction; the invincible array of states and peoples who have thrown off the bonds of the exploiters and are marching forward in the light of the teachings of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin; the advance of the communist movement throughout the world.

After nearly six decades of tireless theoretical and practical activity and political leadership, rising from height to height of achievement and from triumph to triumph, the greatest disciple and successor of Marx and Lenin completed his lifework on March 5, 1953. He was working and giving leadership to the very last hour when the fatal stroke bore down upon him on March 1. He died within nine days of the seventieth anniversary of the death of Karl Marx. And what a lifework in those years from the world of 1895 to the world of 1953—from the darkness of Tsarism to the glory of Soviet emancipation and the transition to communism. Through all the storms of a thunderous dawn, of the dissolution of an old era and the birth of a new, he steered the ship of human hopes and aspirations with unflinching tenacity, courage, judgment and confidence. Now the road lies plain ahead. Departing, he could say with Bunyan: "My sword I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me to be a witness for me."

There are moments in history when an instant sums up an age. Such a moment was when the news of the death of Stalin struck a chill in the hearts of the overwhelming majority of human beings throughout the entire world. The days of grief that followed revealed that the whole world—with the exception of a tiny handful of evil maniacs—mourned the loss of Stalin. Not merely in the socialist world, but from France to India the flags were lowered. That patient file of mourners, ten miles long, and sixteen deep; hour after hour in the icy cold of Moscow’s streets, to pay their last tribute before the bier of Stalin, spoke the great heart of the Soviet people more profoundly and more eloquently than a million ballot boxes.

History knows no parallel to this. When Lenin died, millions and millions mourned him in every country of the world, with a universality that had never before been known for any man in the moment of his death. Hitherto the recognition of greatness across the barriers of countries and continents, of nations and language, of race and colour, has had to await the verdict of generations and of centuries. Communism has changed this. Already through Communism the human race begins to become one kin. Nearly thirty years have passed since the death of Lenin. If millions and scores of millions in every country of the world mourned the death of Lenin, hundreds and hundreds of millions have mourned the death of Stalin. Not merely the thousand million human beings either already in the countries of the camp of socialism or consciously supporting its aims. Also the further hundreds and hundreds of millions, not yet politically awakened, but recognising in the name of Stalin the symbol of the champion of the oppressed and the exploited over the whole earth, the main target of the hatred of the imperialist oppressors and exploiters, the tireless fighter for peace, the shield and bulwark protecting humanity from the horrors of a third world war. Only the tiny handful of fomenters of war, the parasites and their hirelings, reviled him. Like a penetrating searchlight, the loss of Stalin laid bare the contours of the modern world; the light and the darkness; the masses of the common people, and the ravening enemies of humanity; the friends and the enemies of progress; who is for peace and who is for war.

(4) John Gollan, speech (28th December, 1974)

Raji Palme Dutt’s contribution to the founding and development of our Party was great indeed. A foundation member, he was the youngest member of our Executive Committee for many years, joining at first in 1923 and continuing in it for 42 years. In 1985 when, along with his close comrades Peter Kerrigan and John Ross Campbell, he left the EC to make way for younger comrades, we said at our national congress in that year: ‘The tremendous debt our Party owes to these comrades who were amongst the small band who laid the foundations of our Party is impossible to exaggerate.’

But even before this, he was beginning to make his mark in British political affairs, and in giving leadership to the movement. For it was in 1921 that he founded Labour Monthly. This journal, with its world-wide reputation, and particularly his brilliant ‘Notes of the Month’, influenced the British labour movement for over half a century, From the beginning, he was the journal’s editor—an editorship which lasted 53 years.

It was a prodigious task, yet at the same time he did many other things. He was head of our International Department and attended many international congresses. He was a lifelong staunch friend of the Soviet Union.

It is a measure of the scope of his contribution to the British and international working class movement that It was for yet another area of activity that he was possibly more widely known here and throughout the world. His books and writings on fascism, imperialism and colonialism are not only an outstanding contribution to the science of Marxism-Leninism: they alerted, inspired and guided countless thousands of working people in Britain and abroad.

(5) Jim Higgins, International Socialism (February 1975)

As a member of the executive and editor of Labour Monthly, Dutt occupied the role of leading theoretician as populariser and apologist for the line of the Comintern in whatever direction it happened to be moving. Labour Monthly in the early years was required reading for anyone with a theoretical turn of mind and a desire to see theory turned into practice. At one time or another almost every ‘left’ wrote for the magazine, and in the process exposed themselves more effectively than volumes of marxist critique. At no time, however, did Labour Monthly stray far from the line of Palme Dutt’s Russian mentors. Not a single zig of Comintern policy, not yet a zag or even both at the same time failed to find support in the Notes of the Month modestly signed “RPD”. The Anglo-Russian Committee, policy towards the TUC “lefts”, the so-called “third period” policy of “class against class” and the “popular front”, all were joyfully taken on board and extolled as the latest revealed truth. Even so if the Notes were long, complex and seemed more an exercise in squaring the circle than dialectics they were interesting if only to try and see how the trick was done.

As a fluent Russian speaker Dutt was well placed as a link with and interpreter of the directives emanating from Moscow. That this was not always appreciated by less loftily connected comrades is evident from the words of Ernie Cant (London District Secretary): “... once again Comrade Dutt intervenes at the last minute in a party discussion, crossing the t’s and dotting the i’s and giving pontifical blessing to Comrade Pollitt. But Comrade Dutt has not only been divorced from the masses he has been divorced from the actual life of the party for a considerable period – he knows only resolutions, theses, ballot results and newspaper clippings.” But as every Catholic knows and perhaps Ernie Cant had forgotten, the “pontiff” gets his authority from God. RPD’s deity was in Moscow and smiling on his protegé.

Interestingly enough the dispute that occasioned Cant’s outburst occurred in 1929. It concerned the lack of fervour with which the British CP leadership were introducing the “third period” policy. Dutt, Page Arnot and J.T. Murphy led the “ultra left” opposition of Comintern loyalists. So acrimonious did the dispute become that it finally had to be sorted out in Moscow. There the majority of the leadership were transformed into a minority. Harry Pollitt who changed sides just in time was made party secretary, the dissident ex-leadership being dumped.

Always a prolific writer, Dutt was in his element justifying the unjustifiable during the whole of the “third period”. If party membership declined, and it did, the party was stronger, because purer. If fascism succeeded in Germany, all to the good because: “After Hitler, us”. In this last context Dutt spent some time preparing a book proving the objectively fascist nature of social democracy, only to find that when the volume was published the “third period” had evaporated into the gaseous vapours of the “popular front”. The prospect of such a failure of vision must disturb the sleep of all votaries of capricious gods.

But the lurch from ultra-left idiocy of “social fascism” to the social pacifism of the “popular front” was a contradiction easily encompassed in Dutt’s own special dialectic.

Together with D.N. Pritt he was an enthusiastic apologist for the Moscow frame-up trials. Russian communists he had known, some as friends, disappeared in the horror of the great purge, not a words, not a whisper escaped Dutt’s lips or his pen to indicate anything but peace and socialist construction were going on in Russia under the avuncular beneficence of Joe Stalin.

The fruitful partnership with Harry Pollitt was interrupted in 1939. Harry with a logicality that years or training had failed to completely overcome had decided, at the outbreak of hostilities, that the war being against fascists must be, an anti-fascist war and so proclaimed it. He had, however, neglected the fact that the Stalin-Ribbentrop pact had been signed. Germany and Russia had a non-aggression pact. Palme Dutt, more versed in the signals, characterised the war as “imperialist”. Pollitt was removed from the secretaryship and returned to boilermaking, while Dutt took over his job, a situation that lasted until Russia entered the war when its character was immediately transformed into an anti-fascist crusade.

To chronicle each twist and turn of Palme Dutt’s devotion to the line from Moscow would be repetitive and tedious. Suffice to say his last big service to the Russian comrades was in 1956 when he stumped the country, attempting to calm the fears of party members distressed by Khruschev’s revelations at the 20th Party Congress and the Russian crushing of the Hungarian revolution. Palme Dutt’s discourse in justification of Stalin, was know as the “spots on the sun” speech. The sun, according to Dutt, is the source of energy, life, growth and was an all round good thing to have, nevertheless, there are spots on the sun: so it was with Stalin. The argument, for once, did not go down well with the comrades. Over 7,000 left the party and the monolith cracked in a way that defied restoration.

(6) Duncan Hallas, Socialist Review (September 1993)

Dutt soon became a channel for the transmission of the line of the Stalinist centre in Moscow, both before and after the counter-revolution of 1928-9.

In May 1924 Dutt went to live in Brussels, alleging ‘ill health’ as the reason, and stayed there for more than ten years. He had obviously been recruited to the Comintern apparatus.

Yet all this time Dutt remained in the leadership of the British party and edited the Labour Monthly from afar. Month by month, his Notes of the Month arrived from Brussels, like papal encyclicals, expounding and defending every twist and turn of the Stalinist line with never a backward glance or explanation. It supported the rightist line of the CPGB in the run up to and during the 1926 general strike, the turn to lunatic ultra-leftism in 1928-29 (which met with strong resistance at first in the British party) and then the abandonment of class politics altogether with the popular front. All with the calm assurance of a first class shyster lawyer defending a gangster boss.

After his transfer back to London in 1935 Dutt continued in the same vein. He repeated every vile slander against Trotsky and his followers and against the old Bolsheviks murdered by Stalin through the 1930s, praising the obscene parodies of trials that condemned them as ‘Soviet justice’.

After years of arguing for a war against fascism he suddenly discovered (as soon as the Stalin-Hitler pact was signed in August 1939) that the war that ensued was an imperialist war, and then less than two years later, without turning a hair, that it was a patriotic war for democracy.

ft is wearisome to continue an account of the life of this scoundrel. For Callaghan to represent him as a genuine Communist is an insult to the intelligence of his readers.

A final note is necessary. When, in 1956, Khrushchev, the boss of the USSR, denounced some of Stalin’s crimes in his famous secret speech (not published in the USSR of course) Dutt sought to brush it aside with these words: “That there should be spots on the sun would only startle an inveterate Mithras worshipper ...”

This was one cynicism too many, even for the core leadership of the CPGB, let alone the membership. Pollitt, the general secretary, felt obliged to resign; up to a third of the membership left over the next couple of years. Dutt’s influence was at an end. Unfortunately it had lasted 25 years too long.