John Freeman (original) (raw)

Sections

- John Freeman - Government Minister

- Keep Left Group

- Face to Face

- Editor of New Statesman

- John Freeman - Diplomat

- London Weekend Television

- Primary Sources

- References

John Freeman, the son of Horace Freeman, a barrister, was born on 19th February, 1915. Hugh Purcell has claimed: "The son of a chancery barrister from whom he inherited a hard, analytical mind. His father was nothing if not remote. He invited his son to eat with him once a week; after that, it was by appointment." (1)

Freeman was educated at Westminster School. In 1932 he met Ellen Wilkinson, the leader of a Hunger March to London, and became a socialist. After hearing a speech by Richard Stafford Cripps he joined the Labour Party. (2) He then attended Brasenose College, Oxford. It is claimed he wasted his time at university: "He drank heavily, gambled and chased women, only just emerging from his father’s college, Brasenose, with a degree. Perhaps he found success too easily as he would through all his future careers. Certainly he found womanising easy. He was handsome, with wavy red hair, blue eyes and a fit, slim body. Above all, he had a distant self-sufficiency that women considered a challenge." (3)

In 1937 John Freeman left university and found work as an advertising consultant. In 1940 he joined the Coldstream Guards to be commissioned a year later into the Rifle Brigade. During the Second World War he fought with the "7th Armoured Division from El Alamein to Salerno and then through Caen to Hamburg." (4) Promoted to the rank of major he won the MBE in 1943. General Bernard Montgomery called him "the best brigade major I have". He told fellow officers “I want you to know that I have been a passionate socialist ever since I was at Oxford and I am today an even more convinced socialist than ever.” (5)

In the 1945 General Election Freeman won Watford. In his maiden speech in the House of Commons he argued: "On every side is a spirit of high venture, of gay determination, a readiness to experiment, to take reasonable risks, to stake high in this magnificent venture of rebuilding our civilisation, as we have staked high in winning the war... Today we go into action. Today may rightly be regarded as D-Day in the Battle of the New Britain." (6) It is claimed that the speech moved Winston Churchill to tears. He apparently said: “Now all the best young men are on the other side.” Barbara Castle commented: “John was a charismatic figure who seemed to have a dazzling career in front of him. As he stood there in his major’s uniform, erect, composed and competent, everyone felt his star quality.” ( 7)

John Freeman - Government Minister

Clement Attlee was impressed by Freeman and held ministerial posts in both the War Office and the Ministry of Supply. In November 1950 Hugh Gaitskell became chancellor of the exchequer. This move angered the left of the party. Aneurin Bevan sent a letter to Attlee commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement." (8)

As a result of the Korean War the British government came under pressure to increase defence spending. Attlee eventually agreed to increase the British defence budget from £3,400 million to £4,700 million. Harold Wilson (Board of Trade) disagreed with this policy as he thought that any attempt to reach the target would be disastrous to the British economy. This view was shared by Freeman, Bevan and John Strachey (Secretary of State for War) but Gaitskell insisted that he would be able to find the money to pay for the increased spending on defence.

Gaitskell decided that one way of obtaining this money was by making cuts to government spending. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Gaitskell told his colleagues that he intended imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the NHS. Wilson, Bevan and Freeman all threatened to resign.

John Freeman

Jennie Lee, recalls in her autobiography My Life With Nye (1980) that the men met at the Bevan home: "Harold Wilson, the President of the Board of Trade, John Freeman, the Junior Minister but the driving force in the Ministry of Supply, and John Strachey, the Minister of War, met at our home to discuss what best to do. They shared Nye's indignation over the folly of imposing health charges, and felt even more strongly the insanity of promising an arms programme we could not carry out even by borrowing money from America to pay for it. Why should not each country contribute according to its resources? That is how the argument ran. Nye made clear that as he had stated publicly as well as in the Cabinet that he could not remain a member of the Government if health charges were imposed, he intended to resign, but he asked his friends not to do so. He had an educational job to do that would absorb all his energies, but he did not want the split in the Party to be deepened by other resignations. Wilson and Freeman said they had had enough. They too would resign and make clear their reasons for doing so. John Strachey sat squirming by our sitting-room fireside enjoying exquisite thrills, but he had no intention of resigning." (9)

Attempts were made to bribe the three men. Wilson was offered a safe seat in the next election. Freeman was offered Wilson job in the Cabinet if he carried out his threat to resign. Herbert Morrison resorted to threats and told Wilson that if he resigned he "would be finished in Labour politics for twenty years." (10) Gaitskell hoped that the three men would resign. He told Hugh Dalton, "We'd be well rid of the three of them!" (11) James Callaghan told his contact at the American Embassy that even though Wilson and Bevan had threatened to resign "there was virtually no sympathy within the party" for the men. (12) Wilfrid Macartney, a long-time friend, wrote to Bevan warning him not to resign: "Don't go into the wilderness unless like Moses you can take the tribes with you, and remember he was there for forty years." (13)

John Freeman also warned Bevan against resigning as he thought it would seriously damage his chances to lead the Labour Party in the future. "The Budget is popular in the Parliamentary Party, even among those who have indicated sympathy for your point of view. It will be popular, though perhaps less so, in the Labour movement in the country. If you resign now on the Budget there will be amazement as well as anger among our colleagues, and the consequences to the Party which would in any circumstances be extremely grave, will be catastrophic. Your own position, and the views we share will be, for some time ahead, seriously compromised. The impending election will find us disunited, without policy and with the reactionaries in full charge of the Party machine which will be used unscrupulously against you and those who stand with you. The result will be a debacle of 1931 proportions - and little or nothing gained."

Freeman argued that Bevan should resign later over another issue: "If you could find some way of not making your resignation public at this moment and on this issue, you would not lack the opportunities in coming weeks - perhaps even days - to go out on an issue to which millions of Labour supporters would rally enthusiastically - the drive towards war, the absence of any coherent foreign policy, the inflationary and anti-working class character of our rearmament economies. The split on all this would be just as big; we should still probably lose the election, though not by so much; but three-quarters of the Labour movement would rally to you, and would hold the initiative and have a good chance of capturing the machine. I beg you to think long and earnestly before you throw away this tremendous opportunity which I believe to be close at hand." (14)

Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973) has argued: "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year - by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon." (15)

The following day, Aneurin Bevan resigned from the government. In a letter to Clement Attlee Bevan explained his actions: "In previous conversations with you, and in my statements to the Cabinet, I have explained my objections to many features in the Budget. Having endeavoured, in vain, to secure modifications of these features, I feel I must ask you to accept my resignation. The Budget, in my view, is wrongly conceived in that it fails to apportion fairly the burdens of expenditure as between different social classes. It is wrong because it is based upon a scale of military expenditure, in the coming year, which is physically unattainable, without grave extravagance in its spending. It is wrong because it envisages rising prices as a means of reducing civilian consumption, with all the consequences of industrial disturbance involved. It is wrong because it is the beginning of the destruction of those social services in which Labour has taken a special pride and which were giving to Britain the moral leadership of the world. I am sure you will agree that it is always better that policies should be carried out by those who believe in them. It would be dishonourable of me to allow my name to be associated in the carrying out of policies which are repugnant to my conscience and contrary to my expressed opinion." (16)

Hugh Purcell has argued that Clement Attlee tried hard to keep Freeman in the government summoning him to the hospital where he was recovering from a duodenal ulcer and offering him Wilson’s post in the cabinet as president of the Board of Trade. "He (Attlee) saw him as a mediator between Gaitskell, who thought highly of Freeman, and Bevan; quite possibly as a future leader. But once Freeman made his mind up he never changed it. He knew he was a favoured son." (17) Freeman said in his resignation speech: “In laying down the responsibilities of office I am also giving up the fruits of office.”

Keep Left Group

Wilson, Bevan and Freeman now joined what was known as the Keep Left Group. Other members included included Richard Crossman, Sydney Silverman, Konni Zilliacus, Barbara Castle, Jennie Lee, Tom Driberg, John Platts-Mills, Lester Hutchinson, Leslie Solley, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, William Warbey and Michael Foot. As one of its members, Ian Mikardo has pointed out: "The Group was radically changed, as was almost everything else in and around the Labour Party, when Aneurin Bevan, Harold Wilson and John Freeman resigned from the Government in 1951. Overnight we were transformed, not by ourselves but by the media, from the Keep Left Group to the Bevanites... In 1951 there were thirty-two of us, and by the following year that number had risen to forty-seven MPs and two peers." (18)

Freeman was not very active in the Keep Left Group: "Freeman’s personal principles were stronger than his political convictions. It would explain, too, why he seemed to lose the stomach for the fight. Barbara Castle travelled around the country with him, expecting him to take a lead in arguing the Keep Left case to Labour supporters, but she was disappointed. In one stormy meeting after another he stood against the wall, almost hiding himself behind the window curtains, but did not speak. After years of studying his complex personality (on intimate terms it should be added as they were lovers) I decided he was afraid of giving himself too fully to anything or anyone." (19)

Face to Face

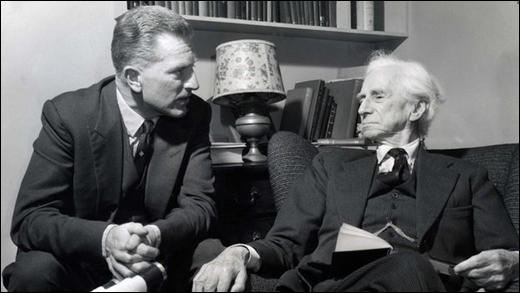

In 1955 John Freeman decided to resign from the House of Commons and become a journalist. Kingsley Martin appointed him as deputy editor of the New Statesman. In 1959 he became the presenter of BBC's Face to Face. Over the next three years he carried out 35 in-depth interviews with people such as Martin Luther King, Carl Jung, Bertrand Russell, Robert Boothby, Hartley Shawcross, Adlai Stevenson, Herbert Morrison, Augustus John, John Reith, Victor Gollancz, Frank Cousins, Tony Hancock, Gilbert Harding, Henry Moore and Stirling Moss.

John Freeman and Bertrand Russell in 1959.

There were some complaints about Freeman's interviews. Michael Leapman points out: "His trademark was his refusal to appear on camera himself, always interviewing with the camera behind his back.... His interviews were sometimes regarded as insensitive, especially by the quieter standards of the day. He explored the insecurities of the comedian Tony Hancock and the TV panellist Gilbert Harding, who confessed in tears to being shattered by his mother’s death." (20) Kingsley Martin commented: “John is the only man who has made himself celebrated by turning his arse on the public.” Hugh Purcell pointed out: "The viewer never saw his face. He sat with his back to the camera, in the shadow, smoke from a cigarette curling up between the fingers of his right hand. Freeman was the Grand Inquisitor, exposing the person behind the public figure, but never his own." (21)

Editor of New Statesman

In 1961 John Freeman became editor of the New Statesman. One of his first acts was to fire his friend Tom Driberg, the magazine’s television critic, although he knew that he was in dire financial straits. (22) One of his colleagues, Anthony Howard, later wrote: "When he came to the job... sales were falling – the old formula of pacific socialism and optimistic sentiment had begun to look rather faded – he rapidly reversed the trend, leaving behind him four years later a circulation over 90,000: those were the days. It was, in some ways, an improbable achievement. Freeman was never an easy writer – it would sometimes take him as much as two hours to compose a single paragraph for his London Diary. But what he lacked in fluency or flair he more than made up for in administrative and editorial efficiency. The New Statesman of his day was run as a tight ship, with Freeman every inch the captain. He set himself high standards and expected, and exacted, them from his staff – whom he would always, however, loyally defend in the face of any outside criticism." (23)

Freeman moved the journal to the right. Unlike the former editor, he did not support the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Hugh Purcell has argued: "I think there are two kinds of journalists. One that wants to expound a situation and one, like Kingsley, who wants to redress a situation. Kingsley is a preacher and he doesn’t care much about facts. When he was absolutely certain about his tenets he wrote like an angel. The decline in his writing is to do with the decline in his certainty. Freeman had no such doubts. He thought it would be self-destructive at the height of the cold war for Britain to leave Nato, which unilateral disarmament would necessitate. When he became editor, the journal’s quasi support for CND ceased. During the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 the New Statesman backed President Kennedy throughout: more so, in fact, than even the Daily Telegraph, which stated that the United States should have acted through the United Nations. (24)

Freeman continued to have a complicated love-life. His first wife, Elizabeth Johnson, divorced him in 1948. His second wife, Margaret Kerr, died in 1957. After a long affair with Catherine Dove, the wife of Charles Wheeler, they married in 1962. He also had a relationship with the novelist, Edna O’Brien, who later wrote a short story about it called The Love Object. In the tale the "woman is infuriated by the married man’s habit of folding his trousers too precisely before getting into bed with her". (25)

Terence Rattigan also wrote about Freeman in a BBC play, Heart to Heart. The play is about a TV interviewer who drank too much and was a womaniser. Freeman thought it was libellous. He protested that: “The allegation of alcoholism I just about accept; that of amorousness I reject absolutely.” Freeman consulted a lawyer and eventually the matter was settled without legal action being taken. (26)

John Freeman - Diplomat

After the 1964 General Election his old friend, Harold Wilson, became Prime Minister. Freeman welcomed the appointment of Barbara Castle as Minister for Overseas Development. Freeman wrote in the News of the World: "The woman who have ever served in the British Cabinet can be counted on the fingers of one hand. But even in this honoured group, Barbara Castle stands out like Miss World at a meeting of the Women's Institute. Let nobody, however, be deceived by her spectacular charms. This is one of the toughest and ablest of our politicians... even her bitterest political enemies - and she has a few - would agree that she has the capacity to rise further." (27)

In 1966 Harold Wilson asked John Freeman him to go to Delhi as high commissioner to India. It was at a time when the country was threatening to leave the Commonwealth. Wilson had upset the Indian government by appearing to sympathise with Pakistan in the conflict between the two countries. Freeman’s quiet diplomacy did much to defuse this. He held the post until 1969. (28)

John Freeman, now an established diplomat, was posted to Washington. This was a difficult time for Freeman who had to deal with the recently elected Richard Nixon. During the 1964 Presidential Election had bitterly attacked Nixon him in the New Statesman as “a discredited and outmoded purveyor of the irrational and inactive” whose defeat would be “a victory for decency”. Despite this unpromising background " he forged an improbably cordial relationship with President Nixon." (29) Freeman formed a fruitful relationship with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He reported back that Kissinger commented on Nixon’s staff. “I have never met such a gang of self-seeking bastards in my life... I used to find the Kennedy group unattractively narcissistic, but they were idealists. These people are real heels.” (30)

After the Conservative Party victory in the1970 General Election, Freeman returned to England. He was the first ambassador in 55 years who went and returned without a knighthood or a peerage. He rejected both, saying “when it can be proved that I can do my job better by changing my name, then I might consider it”. Richard Crossman met him in London and wrote in his diary: "John used to be a rather willowy, elegant young man with wonderful wavy hair but he’s thickened out and his complexion has roughened so that he looks like an extremely tough colonel of a polo-playing regiment just back from India – big and bluff." (31)

Freeman told the economist Robert Cassen. "I believe you should change your life as much as possible every decade.” Freeman was as good as his word, because he was having another affair, with his social secretary, Judith Mitchell. She later became his fourth wife after his hurtful, protracted divorce from Catherine Dove Freeman. He and Judith would have two daughters, Jessica and Victoria, the second when he was 71. (32)

London Weekend Television

In 1971 Freeman become chairman and chief executive of London Weekend Television (LWT). "The company was then in dire financial straits but was transformed by a combination of Freeman’s ruthless administrative skills and understanding of the television media." (33) Hugh Purcell has pointed out: "The company was saved. A thousand employees kept their jobs. Freeman, it is worth recalling, had been out of the country for the previous six years and had no experience of running a big company. 'He was,' the official history continued, 'one of those rare men of parts who seem to be able to do anything better than anybody else.' No wonder he became bored quickly. Even the most demanding job was just too easy." (34) He remained at LWT until 1984, during part of which time he was also chairman of Independent Television News, governor of the British Film Institute and Vice-President of the Royal Television Society.

From 1985 to 1990 he was visiting professor of international relations at the University of California. (35) On his return to London he took up the game of bowls. At the age of 78, he become Southern Area champion. Hugh Purcell claims that bowls was "a sport that obviously played to his strengths, as it requires a cool nerve and a killer instinct." Purcell later wrote: "I was by now fascinated by Freeman’s life, and particularly by this combination of public celebrity with impenetrable privacy. I wanted to write his biography." Freeman refused to cooperate and the book was never published. (36) Nor did Freeman write his autobiography and very little about himself, despite many years as a journalist.

John Freeman died aged 99 on 20th December 2014.

Primary Sources

(1) John Freeman, speech at the House of Commons (July, 1945)

On every side is a spirit of high venture, of gay determination, a readiness to experiment, to take reasonable risks, to stake high in this magnificent venture of rebuilding our civilisation, as we have staked high in winning the war.

(2) John Freeman, letter to Aneurin Bevan (10th April, 1950)

The Budget is popular in the Parliamentary Party, even among those who have indicated sympathy for your point of view. It will be popular, though perhaps less so, in the Labour movement in the country. If you resign now on the Budget there will be amazement as well as anger among our colleagues, and the consequences to the Party which would in any circumstances be extremely grave, will be catastrophic. Your own position, and the views we share will be, for some time ahead, seriously compromised. The impending election will find us disunited, without policy and with the reactionaries in full charge of the Party machine which will be used unscrupulously against you and those who stand with you. The result will be a debacle of 1931 proportions - and little or nothing gained.

If you could find some way of not making your resignation public at this moment and on this issue, you would not lack the opportunities in coming weeks - perhaps even days - to go out on an issue to which millions of Labour supporters would rally enthusiastically - the drive towards war, the absence of any coherent foreign policy, the inflationary and anti-working class character of our rearmament economies. The split on all this would be just as big; we should still probably lose the election, though not by so much; but three-quarters of the Labour movement would rally to you, and would hold the initiative and have a good chance of capturing the machine. I beg you to think long and earnestly before you throw away this tremendous opportunity which I believe to be close at hand.

The assurances I gave you this afternoon are in no way modified or withdrawn; but they do give me the right to address this last appeal to you.

(3) Jennie Lee, My Life With Nye (1980) page 189-190

Harold Wilson, the President of the Board of Trade, John Freeman, the Junior Minister but the driving force in the Ministry of Supply, and John Strachey, the Minister of War, met at our home to discuss what best to do. They shared Nye's indignation over the folly of imposing health charges, and felt even more strongly the insanity of promising an arms programme we could not carry out even by borrowing money from America to pay for it. Why should not each country contribute according to its resources? That is how the argument ran. Nye made clear that as he had stated publicly as well as in the Cabinet that he could not remain a member of the Government if health charges were imposed, he intended to resign, but he asked his friends not to do so. He had an educational job to do that would absorb all his energies, but he did not want the split in the Party to be deepened by other resignations. Wilson and Freeman said they had had enough. They too would resign and make clear their reasons for doing so. John Strachey sat squirming by our sitting-room fireside enjoying exquisite thrills, but he had no intention of resigning.

(4) Hugh Purcell, The New Statesman (7th March, 2013)

“I wish everybody would forget I was alive,” he said. And most people did. But John Freeman, now in his 99th year, is still living a very private life at a nursing home in south London. He is one of the most extraordinary public figures of the postwar period; an achiever and thrower away of high office after high office; a celebrity who sought anonymity. “John Freeman,” said an old friend, “has spent his life moving through a series of rooms, always shutting the door firmly behind him and never looking back.”

In the 1940s he was a war hero, and then an MP who reduced Winston Churchill to tears in the Commons. In the 1950s he was tipped to become Labour leader but resigned from politics and became a TV interviewer. In 1961 he resigned from the BBC and became the editor of the New Statesman. Four years later he resigned and became a diplomat, working first as Britain’s high commissioner to India and then as the ambassador to Washington. In 1971 he resigned and became the chairman of London Weekend Television and then Independent Television News. In 1984 he moved to California to teach, until his return and retirement in 1990. In old age, he still did not look back. In 2005 he wrote: “When I retired from even the outer reaches of public responsibility, I resolved to put that life completely out of mind – to forget it all, in fact.”

The paradox of Freeman the private celebrity was symbolised by the TV series that made him famous from 1959 onwards, Face to Face. The viewer never saw his face. He sat with his back to the camera, in the shadow, smoke from a cigarette curling up between the fingers of his right hand. “John is the only man who has made himself celebrated by turning his arse on the public,” said Kingsley Martin, the then editor of the New Statesman. Freeman was the Grand Inquisitor, exposing the person behind the public figure, but never his own....

Thirty years later the BBC repeated Face to Face and sent the radio psychiatrist Anthony Clare (of In the Psychiatrist’s Chair fame) and me to California to film an introductory interview in which the roles were reversed. The programme was a failure. Freeman had an intimidating physical presence and a manner that combined an old-fashioned, somewhat insincere charm with his thoroughgoing put-downs: “I’m sorry, I don’t want to sound rude to you – but that’s the sort of portentous question I don’t think I want to answer.” As always, he gave nothing away. An old friend of his had warned me: “John has a capacity to put up the shutters that is excelled by nobody except a shopkeeper during a time of riots.”

Freeman found a house in London and it was here, a few weeks later in 1971, that he was visited by a desperate David Frost, the joint founder of London Weekend Television. Frost’s company was in a mess and the Independent Television Authority (ITA) was threat ening to remove its licence. The managing director, Michael Peacock, had been fired and the heads of several programme departments had resigned. Viewers were switching off; shareholders wanted out. The company, in fact, was being run by Rupert Murdoch, who had saved it by buying £500,000 worth of shares, then taking his coat off and directing the day-to-day management although he had no right to do so as a non-executive director. The ITA disapproved of Murdoch. He was breaking the rules; he was not a UK resident and he was a major newspaper proprietor. Murdoch was “dangerously angry”. LWT had been given six weeks to find a new managing director.

Enter Freeman, deus ex machina. LWT’s chairman, Aidan Crawley, was pushed upstairs to become the nominal president and Freeman became the new chairman and managing director, with a free hand to control Murdoch and impress the ITA. He wrote: “I had very strong views about how the company should be run, but frankly I didn’t give a bugger whether I stayed or not – I merely had to do the best I could.”

He moved into bleak, 17th-floor offices on the North Circular Road. A month later he led a delegation of ten for an all-day crunch meeting at the ITA. According to Jeremy Potter’s Independent Television in Britain: Politics and Control (1968-80): “He fielded most questions himself and was authoritative and convincing. No one doubted he was in control.”

The company was saved. A thousand employees kept their jobs. Freeman, it is worth recalling, had been out of the country for the previous six years and had no experience of running a big company. “He was,” the official history continued, “one of those rare men of parts who seem to be able to do anything better than anybody else.” No wonder he became bored quickly. Even the most demanding job was just too easy.

(5) Dennis Barker, The Guardian (21st December, 2014)

John Freeman, who has died aged 99, was a human chameleon: he took up and discarded one impressive career after another. He was by turns an advertising copywriter, an army major and decorated second world war hero, a Labour politician and minister, a dangerously incisive television interviewer whose Face to Face series made a considerable mark, an editor of the New Statesman magazine, a senior diplomat, a TV executive and a professor of international relations – to all of which he brought an elusive charm and a notable efficiency. When he had made a success of each, he simply decided to move on.

After serving as a Desert Rat – a member of the 7th Armoured Division in North Africa – in 1945 he won the parliamentary seat of Watford for Labour. His maiden speech, about the rebuilding of postwar Britain, moved Winston Churchill to tears. Freeman quickly became a junior minister and was tipped by some as a future party leader. But in 1951 he resigned his office and in 1955 left politics altogether to begin his serial march through successful careers.

Freeman then morphed into a diplomat: Labour returned to power in 1964, and he secured the post of British high commissioner to India (1965-68), and then British ambassador to Washington (1969-71). A more hands-on task presented itself when the broadcaster David Frost asked him to become managing director and chairman of the troubled London Weekend Television (1971-84). He went in and rescued it from disaster, although he had had no previous experience of running a company of any kind. His final role came as professor of international relations at the University of California, Davis (1985-90)...

He was married four times: in 1938 to Elizabeth Johnston; following their divorce, in 1948 he married Margaret Kerr, who died in 1957, leaving him a stepdaughter, Lizi, whom he adopted. In 1962 he married the Panorama producer Catherine Dove, with whom he had three children, Matthew, Tom and Lucy. He and Catherine divorced, and in 1976 he married Judith Mitchell, with whom he had two daughters, Victoria and Jessica. He also had affairs with the Labour politician Barbara Castle and the novelist Edna O’Brien. He is survived by Judith and his six children.

(6) The Daily Telegraph (21st December, 2014)

John Freeman was born in London on February 19 1915, the son of a well-known, if eccentric, barrister, Horace Freeman. He was educated at Westminster and Brasenose College, Oxford, where he took a Third in Greats and edited Cherwell.

He then went into advertising as a copywriter and in 1940 joined the Coldstream Guards to be commissioned a year later into the Rifle Brigade. He fought with the 7th Armoured Division from El Alamein to Salerno and then through Caen to Hamburg. He was appointed MBE in 1943.

He had become a socialist during the war and in 1945 won Watford in a result that was sensational even in a year when many Tory bastions fell. The prime minister, Clement Attlee, chose him to move the Loyal Address in reply to the Gracious Speech opening that historic parliament.

It was a tour de force. Freeman, tall and handsome with a shock of ginger hair and in his major’s uniform carrying the Desert Rats insignia, reduced Winston Churchill to tears of emotion when he congratulated him in the Smoking Room afterwards.

Promotion came rapidly, first as financial secretary to the War Office and then parliamentary secretary, Ministry of Supply, with the task of getting steel nationalisation through the Commons. His speech winding up the second reading of that bitterly contentious bill was another parliamentary triumph winning plaudits from even its fiercest enemies on the Tory benches.

A golden future seemed to lie ahead, but in 1951 Freeman joined Aneurin Bevan and Harold Wilson in resigning from the government over Hugh Gaitskell’s Health Service cuts; while they made charges for spectacles and false teeth the emotive issue, Freeman challenged the Korean War rearmament estimates on which Gaitskell’s budget was based...

John Freeman’s character was shaped by ambition and restlessness; boredom set in easily. “John Freeman,” said one friend, “spent his life moving through a series of rooms, always shutting the door firmly behind him and never looking back.” Towards the end of his life he even distanced himself from the Labour party, describing Tony Blair as “ineffably insufferable”.

This sense of perpetual motion was reflected in his personal life. Freeman was married four times, with six children, having become a father for the final time in his seventies. In 1938 he married Elizabeth Johnson. Their marriage was dissolved a decade later and in 1948 he married, secondly, Margaret Kerr, who died in 1957 (he adopted his stepdaughter). In 1962 he married, thirdly, Catherine Dove, with whom he had two sons and a daughter. Meanwhile, he began an affair with the Irish novelist Edna O’Brien, who wrote a short story about it, The Love Object (1968) - in the tale the woman is infuriated by the married man’s habit of folding his trousers too precisely before getting into bed with her.

Catherine Dove became controller of features at Thames Television and, in order to marry Freeman, divorced Charles Wheeler, who was for many years the BBC’s Washington correspondent - which created an interesting situation when Freeman arrived there as ambassador. Their marriage was dissolved in 1976, leaving Freeman free to marry Judith Mitchell, the woman Catherine had chosen to be their social secretary at the Washington Embassy. They had two daughters.

(7) Michael Leapman, The Independent (21st December, 2014)

On 16 August 1945, the day after the official end of the Second World War, Parliament met for the first time following the Labour Party’s landslide victory in the General Election. It was widely understood that the votes of servicemen had been the key factor in Labour’s triumph and Major John Freeman, representing Watford, was one of several new MPs who arrived at the House of Commons in their military uniforms.

He had been chosen to move the Motion on the Address. "This is D-Day for the New Britain," he declared resoundingly; and in some respects it was, although many of the high hopes that he and his fellow socialists entertained for the postwar era would inevitably be dashed. None the less, it was certainly the day that marked the start of the tall, red-headed 30-year-old major’s eclectic and high-flying career as a politician, journalist, diplomat and media executive. Winston Churchill, still adjusting to the unfamiliar role of Leader of the Opposition, predicted that he had an important political career ahead of him, and growled: "They now have all the best young men on their side." Freeman would, in, time, become the last surviving member of the 1945 Parliament...

As soon as he entered Parliament he was singled out as a potential minister, being given a series of junior posts in the War Office until, in 1947 he was appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Supply. Impressive performances at the despatch box confirmed Churchill’s view that here was a politician of great promise. Yet the postwar Labour Government, after its initial burst of enthusiasm and achievement, was becoming increasingly schismatic, with a left-wing faction forming around Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health. Freeman aligned himself with the Bevanites and became a friend and ally of Driberg, an outspoken left-winger. When Driberg married Ena Binfield in June 1951 - a surprising move, since he was a flagrant homosexual - Freeman was his best man.

By that time he was out of the Government. A few weeks earlier, when Bevan resigned, Freeman and Harold Wilson, the President of the Board of Trade, quit in solidarity. The immediate trigger for their action was the imposition of prescription charges in the National Health Service, but Freeman was equally exercised about the amount of money being spent on the armed forces at the expense of the social services. Clement Attlee, the Prime Minister, sought to persuade him to stay on, offering him Wilson’s berth at the Board of Trade, but he refused to change his mind.

His resignation was not as much of a sacrifice as it might have appeared. For one thing, he was becoming disillusioned with Parliament and its self-serving intrigues; and for another he already had a job to go to. A few months earlier he had been approached by Kingsley Martin, who had been editing the New Statesman for 20 years and had established it as the most important weekly political journal in the country, a significant outlet for left-wing thinking. Although still only 54, Martin recognised that at some stage he would have to hand over the reins, and began looking for a successor....

Freeman recognised that provocation would generally draw out more truth from interviewees than politeness. Sitting with the back of his head towards the camera, and with the victim’s face in close-up, he turned the programmes into gladiatorial contests. In an unemotional, forensic style, he would nag away at any weaknesses he perceived in his subjects’ defences. In one notorious programme, the game show panellist Gilbert Harding was reduced to tears during a relentless interrogation about his family history. The series was immensely popular and in 1960 Freeman was named television personality of the year.

His formidably intimidating public persona did not mean, though, that he was devoid of passion and human frailties. He was attractive to women. Ista died in 1957 and a year later he met Catherine Dove, his producer on Press Conference. Although Dove had only recently married Charles Wheeler, a well-known BBC reporter, she and Freeman immediately fell in love. They married in 1962 and had three children.

His several affairs included one with the novelist Edna O’Brien, who wrote a fictional but recognisable account of their initial mutual obsession and its painful ending in a moving short story, The Love Object, published in 1968. She dwelt on his cool precision – asking for a brush to remove a speck of powder from his suit before taking his leave in the morning – and described the collected way in which he eventually ended things: "I adore you but I’m not in love with you, with my commitments I don’t think I could be in love with anyone."

When I interviewed Freeman for my 1982 biography of Murdoch he said the atmosphere when he arrived at LWT was like a casualty clearing station after a major battle. Many senior executives had been fired, and not all had been replaced. Morale was low and nobody was confident that the company had a future. He immediately exercised a calming influence and led LWT into its most fertile decade, when it nurtured such talents as Michael Grade, John Birt, Melvyn Bragg and Greg Dyke.

His personal life had gone through another upheaval. In 1971, a few weeks after departing from Washington, he shocked Catherine by telling her that he was leaving her and their young children to set up house with Judith Mitchell, a South African who had been Catherine’s social secretary at the Washington embassy. It was a rancorous split, with the divorce not finalised until 1976, when Freeman and Mitchell married. They had two daughters.

He quickly earned a reputation as one of the most effective executives in television. He was chosen as chairman of the council of the Independent Television Companies Association from 1974 to 1975, vice-president of the Royal Television Society from 1975 to 1985, a governor of the British Film Institute from 1976 to 1982 and chairman of Independent Television News from 1976 to 1981. During his career he was offered both a knighthood and a peerage but turned them down. Having experienced the frustrations of the House of Commons all those years earlier, he did not relish the prospect of serving time in the Lords.

In 1984, at the age of 69, he stepped down from LWT and from most of his other positions, although for some years he was a visiting professor in international relations at the University of California in Davis. He took up bowls – a game that ideally suited his calm, calculating mind – and became champion of the south of England. In the last years of his life he was afflicted with cancer but, while he shunned the limelight, he retained a lively mind and kept in contact with his closest friends. In 2012 he moved himself to a military nursing home in south London so as not to be a burden on his family.

(8) Alasdair Steven, The Scotsman (27th December, 2014)

John Freeman was an outstanding figure in post-war politics and at the BBC, gaining renown for his skilled interviewing on BBCTV’s Face to Face.

Freeman was never seen on screen – occasionally his right shoulder was spotted – but the cameras and the spotlights concentrated on the subject. It was a forbidding ordeal and many consider the format revolutionised television interviewing.

Gone was the reverential, rather polite, form of bland questioning. Instead Freeman asked pertinent and hard-nosed questions and if he didn’t get an answer he persisted. Freeman never hectored or badgered but remained calm and resolute: always ultra-polite.

The television personality Gilbert Harding broke down in tears and Tony Hancock was visibly agonised. The founder of the BBC, Lord Reith, faced Freeman, who asked succinctly if he had made any mistakes in creating the Corporation. After a pause Lord Reith thundered in heavy Scottish accent, “No”. It all made for gripping television.

John Freeman was the son of a Chancery barrister, attended Westminster School and read English at Brasenose College, Oxford. He had a distinguished career in the army during the war, serving with the Coldstream Guards in the Middle East, North Africa, Italy and North West Europe. He was seconded to the Rifle Brigade and awarded the military MBE for his conduct at Medenine during the advance on Tunis. Field-Marshal Montgomery is reputed to have called Freeman “the best brigade major I have”.

He stood and won Watford for Labour in 1945 and seconded the King’s Speech in the Commons wearing his uniform. Freeman rose to the occasion in heroic terms. “Today we go into action,” he told the House. “Today may rightly be regarded as D-Day in the Battle of the New Britain.” Winston Churchill is said to have listened in tears and commented: “All the best young men are on the other side.”

Freeman was considered a future prime minister but in 1951 he resigned (with Harold Wilson) on charges being imposed on dentures and spectacles. In 1955 Freeman left Parliament to become editor of the Left-wing New Statesman where he remained until 1965.

In 1959 he had started Face to Face and from the outset it was ground-breaking. Felix Topolski’s sketches of the interviewee with Berlioz’s stirring overture to Les francs-juges in the background. Then the cameras zoomed in on the subject with a savage honesty. The nervous fingers holding a cigarette, sweat on the forehead and every nervous flicker of an eyelid captured in black and white close-up.

The stars – of entertainment, politics and literature – queued up to be on the show; including Bertrand Russell, Edith Sitwell, Adlai Stevenson, Henry Moore, Martin Luther King, Adam Faith, Cecil Beaton and Roy Thomson.

Only two were not interviewed in the London studio. Freeman travelled to Zurich to interview Carl Jung and to Edinburgh to interview Sir Compton Mackenzie.

The later was carried out in 1962 in Sir Compton’s flat in the New Town. In his bed, the author was covered in blankets and rugs talking of Scottish independence.

Certainly Freeman was criticised for his aggressive interviewing technique but it soon came to be accepted practice and others such as Robin Day followed Freeman’s example. In truth, Freeman was persistent and assiduous in his questioning. He never descended to scandalous innuendo but had the ability to politely belittle a subject and did so with an unrestrained relish.

In 1971 he became chairman of London Weekend Television and reinvigorated the channel, which was in a sad financial plight. But in 1984 Freeman decided to move on again. He moved to the university at Davis, California as a visiting professor of international relations. In 1992 he finally retired to leafy Barnes where, aged 78, he became a bowls champion. In 2012 he retired to a military care home.