Laurel Garland: Women of the Risorgimento (original) (raw)

****FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE � JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN : WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II,III,IV,V,VI,VII , VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICEAUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES:ITALIANO,ENGLISH || VITA** New: Opere Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence

LAUREL GARLAND:

WOMEN OF THE RISORGIMENTO

Elizabeth Barrett Browning || Madame de Sta�l || Anna Jameson || Theodosia Garrow Trollope || Isa Blagden || Mary Somerville || Jessie White Mario || Anita Garibaldi || Cristina Trivulzio, Principessa Belgioioso || Sarah Parker Remond || Harriet Beecher Stowe || Rosa Madiai || Margaret Fuller || Harriet Hosmer || F�licie de Fauveau || Lily Wilson || Cristina Rossetti

** **nna Jameson prefaced her Loves of the Poets with a quotation from Madame de Sta�l:

**nna Jameson prefaced her Loves of the Poets with a quotation from Madame de Sta�l:

. . . these laurels, whose growth is not of earth, but heaven, were all around me: I had but to gather them from the intermingling weeds and briars, and to bind them into a garland, consecrated to women.

Lord Leighton's cameo on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Tomb of a Poetess with laurel garland.

The laurel wreath laid by the Comune of Florence on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb by Lord Leighton on her 200th anniversary, 2006

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

** **lizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning eloped together from her Wimpole Street sickroom in 1846 and came to Casa Guidi in 1847. Their first glimpse of their new home would have been of its frescoed walls, then covered with laurel garlands. It was at Casa Guidi that Elizabeth gave birth to her child, in 1849, celebrating that event while mourning the Austrian takeover of Tuscany and the downfall of the Mazzini Republic of Rome to the French in that same year in her political poem, Casa Guidi Windows, and it was here in 1850, that she was proposed for Poet Laureate, and here where she wrote her epic poem, Aurora Leigh, whose heroine crowns herself one June day with ivy and not with laurel.

**lizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning eloped together from her Wimpole Street sickroom in 1846 and came to Casa Guidi in 1847. Their first glimpse of their new home would have been of its frescoed walls, then covered with laurel garlands. It was at Casa Guidi that Elizabeth gave birth to her child, in 1849, celebrating that event while mourning the Austrian takeover of Tuscany and the downfall of the Mazzini Republic of Rome to the French in that same year in her political poem, Casa Guidi Windows, and it was here in 1850, that she was proposed for Poet Laureate, and here where she wrote her epic poem, Aurora Leigh, whose heroine crowns herself one June day with ivy and not with laurel.

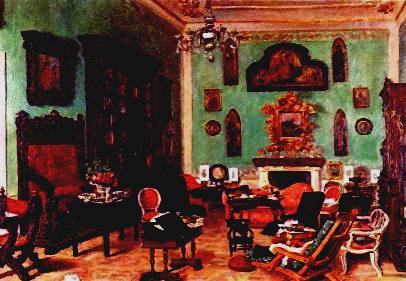

It was in this room that Elizabeth read novels and wrote poems, her favourites being Madame de Sta�l's novel, Corinne ou Italy and those of George Sand. She had as a child studied Hebrew and Greek, and knew the poetry of Homer, Sophocles and Lord Byron intimately, their pictures and their books being her cherished possessions. It was to this room that many other women came, women like the Americans Margaret Fuller, Kate Field, Harriet Hosmer, Harrier Beecher Stowe, and the Englishwomen Anna Jameson, Jessie White Mario, Frances Trollope and Isa Blagden, but not George Sand or George Eliot or Anita Garibaldi or the Princess Belgioioso.

None of these women could attend university. But they could and did write, or sculpt, or heal the sick, or advise nations on freedom. They share a passionate hatred of the abuse of children, of slavery, of the oppression of nations, all as paradigms of their own exploitation as women. In the nineteenth-century they banded together, especially espousing the cause of the Italian Risorgimento. In this essay I shall give portraits of these women, just as much as did Elizabeth Barrett Browning herself adorn its walls, decked with the colours of Beatrice's garb and Italy's then-forbidden flag, with engravings and paintings of poets she loved, and in the same way as would later Lytton Strachey write Eminent Victorians and Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader, and as had Anna Jameson and even Plutarch before them written biographical sketches of great women and men. These women can be her laurel and her ivy, her Casa Guidi Windows opened to the world.

In an earlier lecture at the British Institute I discussed in detail Elizabeth and Robert's family backgrounds as deeply implicated in slavery in the West Indies. Elizabeth Barrett Moulton Barrett was of slave as well as slave-owning stock (her aunt is the famous Pinkie, born in Jamaica, and dying sooner after this painting was finished, and this is Pinkie's brother, Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett, owner of countless slaves). And likewise was Robert, who was also celebrating, in his Bells and Pomegranates his partly Jewish ancestry. We are dealing with Citizens of the Globe, not merely of Italy or of England or of America.

Madame de Sta�l

** **et me begin with Madame de Sta�l (1766-1817), the author of the novel, Corinne ou Italie (1804), which profoundly influenced Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Anna Jameson, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Margaret Fuller. Anne Louise Germaine was the daughter of Suzanne Curchod and supposedly Jacques Necker, the Swiss banker who became France's Minister of Finance in 1776 and 1789. But more likely Edward Gibbon, author of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and who had loved Suzanne Curchod for many years, was her real father. Gibbon, two years before she married, described her to a friend: "Mlle. Necker, one of the greatest heiresses of Europe, is now about eighteen, wild, vain, but good-natured, and with a much larger provision of wit than of beauty." Her husband was to be Eric Magnus, Baron de Sta�l-Holstein, Sweden's ambassador to Paris.

**et me begin with Madame de Sta�l (1766-1817), the author of the novel, Corinne ou Italie (1804), which profoundly influenced Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Anna Jameson, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Margaret Fuller. Anne Louise Germaine was the daughter of Suzanne Curchod and supposedly Jacques Necker, the Swiss banker who became France's Minister of Finance in 1776 and 1789. But more likely Edward Gibbon, author of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and who had loved Suzanne Curchod for many years, was her real father. Gibbon, two years before she married, described her to a friend: "Mlle. Necker, one of the greatest heiresses of Europe, is now about eighteen, wild, vain, but good-natured, and with a much larger provision of wit than of beauty." Her husband was to be Eric Magnus, Baron de Sta�l-Holstein, Sweden's ambassador to Paris.

De Goncourt described her political role:

Madame de Sta�l was a woman of genius as early as the year 1795. . . The daughter of Necker forbade France to recall its line of kings; she retained the republic; she condemned the throne. She agitated victoriously in behalf of the maintenance of the representative system. The human right of victory was equivalent, with her, to the divine right of birth.

She first met Napoleon at a ball given by Josephine, his beautiful Cr�ole wife from the Caribbean islands, toward the close of 1797. Apparently amongst the comments they then exchanged was the following:

Madame de Sta�l: When [a man] has had the fortune to meet with a strong-minded woman, one worthy of sharing his laurels, and herself enjoying a high reputation, then the distance of time and space disappears, for it is the renown of both which serves as messenger between them, and it is through the hundred mouths of fame that each receives intelligence of the other'.

Napoleon: Madame, in what chapter of the work you are now about to publish shall we read this brilliant passage?'

Because of her opposition to him Napoleon saw that she was kept in exile from France. When Napoleon's son, the King of Rome, was born Mme. de Sta�l was informed that her exile could end if she would but write and publish loyal stanzas about the event. She refused.

She next visited England where she was treated with the highest consideration and above all enjoyed the friendship of Lord Byron.

In 1816, she wrote "There is a nation which will one day be very great--the Americans." Only slavery she felt, marred its perfection. "What is more honourable for mankind than this new world which has established itself without the prejudices of the old?--this new world where religion exists in all its fervor without needing the support of the state to maintain it, where the law commands by the respect it inspires although no military power backs it up." In a letter to Thomas Jefferson she wrote, "If you succeeded in doing away with slavery in the South, there would be at least one government in the world as perfect as human reason can conceive it."

Twice she published novels, Delphine first, then Corinne ou Italie. Corinne is an intensely political book. In it a young Scottish nobleman, Oswald, Lord Nevil, finds his childhood friend become an Italian patriot. He witnesses her being crowned with laurel, made Poet Laureate, while dressed as the Sibyl, on the Capitol in Rome and hears her utter political prophetic verses. Perhaps, in this scene on the Capitol, Madame de Sta�l/Corinne was playing with her biological father's conception of his great work, The Decline and Fall of Rome. In her chef-d'oeuvre, she metamorphoses that into the Renaissance, the Risorgimento, of Italy.

But, instead of marrying Corinne, Lord Nevil weds a pallid proper young girl--and Corinne dies of a broken heart. This novel was read and admired by Victorian generations. Though unbeautiful, Madame de Sta�l had herself portrayed as enacting the role of Corinne, by the woman portrait painter, Madame Vig�e Le Brun.

Anna Jameson

** **nna Jameson had come to Italy for the first time in 1821, a buxom twenty-five year old with a head of reddish-blond hair (just the colour of Poetry in Carlo Dolci's painting, Ruskin noted). She was the eldest daughter of an Irish miniature painter of considerable talent, Denis Murphy, Lady Byron in 1841 writing a poem 'On a Portrait of Mrs. Jameson by her Father'. At first she earned her sustenance as a governess, observing that "the occupation of governess is sought merely through necessity, as the only means by which a woman not born in the servile classes can earn the means of subsistence".

**nna Jameson had come to Italy for the first time in 1821, a buxom twenty-five year old with a head of reddish-blond hair (just the colour of Poetry in Carlo Dolci's painting, Ruskin noted). She was the eldest daughter of an Irish miniature painter of considerable talent, Denis Murphy, Lady Byron in 1841 writing a poem 'On a Portrait of Mrs. Jameson by her Father'. At first she earned her sustenance as a governess, observing that "the occupation of governess is sought merely through necessity, as the only means by which a woman not born in the servile classes can earn the means of subsistence".

In moments when she was alone, or if her employers went out to some reception to which she was not invited, Anna Murphy immediately opened two diaries. In the second, she has herself die of a broken heart, the work being published as a governess novel with the title, The Diary of an Enuy�e, modeled upon de Sta�l's_Corinne ou Italie_, but which is also filled with art historical observations. Mrs. Fanny Kemble said, "While under the immediate spell of her fascinating book, it was of course very delightful to me to make Mrs. Jameson's acquaintance, which I did. . . The Ennuy�e , one is given to understand, dies, and it was a little vexatious to behold her sitting on a sofa in a very becoming state of blooming plumpitude".

The Frontispiece is of Beatrice Cenci.

Our visit to the Barberini palace to-day was solely to view the famous portrait of Beatrice Cenci. Her appalling story is still as fresh in remembrance here, and her name and fate as familiar in the mouths of every class, as if instead of two centuries, she had lived two days ago. In spite of the innumerable copies and prints I have seen, I was more struck than I can express by the dying beauty of the Cenci. In the face, the expression of heart-sinking anguish and terror is just not too strong, leaving the loveliness of the countenance unimpaired; and there is a woe-begone negligence in the streaming hair and loose drapery which adds to its deep pathos. It is consistent too with the circumstances under which the picture is traditionally said to be have been painted--that is, in the interval between her torture and her execution. In Florence she notes Artemisia Gentileschi's work: In the gallery there is a Judith and Holofernes which irresistably strikes the attention--if any thing would add to the horror inspired by the sanguinary subject, and the atrocious fidelity, and talent with which it is expressed, it is that the artist was a woman. One morning, as she looked at a red morocco edition of Corinne, a gift to Schlegel from Mme de Sta�l, he confessed himself "immortalized" in it, as "the Prince Castel Forte, the faithful, humble, unaspiring friend of Corinne". She also visits Coppel, Madame de Sta�l's Swiss exile chateau.

In reality, rather than dying of Victorian tuberculosis, Anna Murphy married.

But the marriage failed, and the alcoholic Mr. Jameson went off to Canada.

Because of the failed marriage, Anna could no longer even return to being a governess. She therefore wrote further books: The Memoirs of the Loves of the Poets by the Author of the "Diary of an Ennuy� e, 1829, in two volumes; Memoirs of Celebrated Female Sovereigns, 1831;Memoirs of the Beauties of the Court of Charles II, 1831;Characteristics of Shakespeare's Women. Anna Jameson had a warm temperament, her friends including Ottilie von Goethe, Lady Byron, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and her own niece Geraldine Bate, who married and became Geraldine MacPherson. This is Anna Jameson describing the Coronation of Queen Victoria, whom she knew well:

As to the Queen, though a child, she went through her part beautifully; and when she returned, looking pale and tremulous, crowned and holding her sceptre in a manner and attitude which said 'I have it, and none shall wrest it from me!' even Carlyle, who was standing near me, uttered with emotion a blessing on her head, and he, you know, thinks kings and queens rather superfluous. . . Mrs. Jameson made the acquaintance of Miss Barrett through the good offices of Mr. Kenyon, their mutual friend. Mrs. Jameson was at the time staying next door to the house on Wimpole Street where Miss Barrett resided. This early period of their acquaintance produced a multitude of tiny notes in fairy handwriting, such as Miss Barrett was wont to indite to her friends, and which are still in existence. Some of these are most charming and characteristic, and illustrate the rise and rapid increase of a friendship that never faltered or grew cool from that time up to the death of Mrs. Jameson.

Anna Jameson, with her young niece, helped the eloping Elizabeth Barrett, who was seriously ill, and Robert Robert Browning, who was robust, in Paris and Pisa while on her way to Rome and working on her masterpiece, Sacred and Legendary Art. The couple seemed to have walked out of the pages of her volumes, The Loves of the Poets .

I have also here a poet and a poetess--two celebrities who have run away and married under circumstances peculiarly interesting, and such as render imprudence the height of prudence. Both excellent; but God help them! for I know not how the two poet heads and poet hearts will get on through this prosaic world. I think it possible I may go on to Italy with them. Later her niece who was with her writes: My aunt's surprise was something almost comical, so startling and entirely unexpected was the news. But it was as delightful as unexpected, and gave an excitement the more to our journey, which, to one of us at least, was already like a journey into the world of enchantment--a revival of fairyland . . . The loves of the poets could not have been put into more delightful reality before the eyes of the dazzled and enthusiastic beholder; but the recollections have been rendered sacred by death as well as by love. . . . We rested for a couple of days at Avignon, the route to Italy being then much less direct and expeditious, . . . and while there we made a little expedition, a poetical pilgrimage, to Vaucluse. There, at the very source of the 'chiare, fresche e dolci acque,' Mr. Browning took his wife up in his arms, and, carrying her across through the shallow curling waters, seated her on a rock that rose throne-like in the middle of the stream. Thus love and poetry took a new possession of the spot immortalized by Petrarch's loving fancy. At Pisa, Geraldine assisted Anna with drawings and cups of tea. Outlines were drawn, tracings made, careful drawings put on the wood and sent home to be engraved for the illustrations. The plates of the Campo Santo at Pisa for Sacred and Legendary Art would cause the young painters, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Everart Millais, to form the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The exquisite drawings made for her book are at Baylor University's Armstrong Browning Library. Anna Jameson wrote to Lady Byron, "Not often have four persons so different in age, in pursuits--and under such peculiar circumstances been so happy together."

In 1857 Anna Jameson lived around the corner from Casa Guidi in Via Maggio; like Elizabeth, she was to die, in 1860, without seeing Italian liberation succeed.

Theodosia Garrow Trollope

heodosia Garrow and Elizabeth Barrett Browning already knew each from Torquay in Devon where Elizabeth had been sent because of her tuberculosis, an illness she shared with Theodosia. Like Elizabeth, she was small and exotic, her own background being part East Indian, part Jewish, and from this she is partly the model for Nathaniel Hawthorne's Miriam in The Marble Faun. Both Theodosia and Elizabeth were to come to Florence where Theodosia met and married Thomas Adolphus Trollope, bearing him the child Bice, Pen's playmate, translating Niccolini's plays, supporting the Risorgimento, until her own early death.

heodosia Garrow and Elizabeth Barrett Browning already knew each from Torquay in Devon where Elizabeth had been sent because of her tuberculosis, an illness she shared with Theodosia. Like Elizabeth, she was small and exotic, her own background being part East Indian, part Jewish, and from this she is partly the model for Nathaniel Hawthorne's Miriam in The Marble Faun. Both Theodosia and Elizabeth were to come to Florence where Theodosia met and married Thomas Adolphus Trollope, bearing him the child Bice, Pen's playmate, translating Niccolini's plays, supporting the Risorgimento, until her own early death.

Isa Blagden

** **lizabeth set her epic poem's most important Dantesque-scene at Bellosguardo. She knew of it because of her friend, Isa Blagden . Isa is likewise the model for Miriam in Nathaniel Hawthorne's Romance, The Marble Faun. Alfred Austin said of her: "The news, 'Isa is coming,' invariably thrillled with an almost childlike delight a certain Florentine circle." "She gloried in the gorgeous apparel of the external world, just as--many will remember--she delighted in bright textures and vivid colours for feminine adornment." Kate Field said:

**lizabeth set her epic poem's most important Dantesque-scene at Bellosguardo. She knew of it because of her friend, Isa Blagden . Isa is likewise the model for Miriam in Nathaniel Hawthorne's Romance, The Marble Faun. Alfred Austin said of her: "The news, 'Isa is coming,' invariably thrillled with an almost childlike delight a certain Florentine circle." "She gloried in the gorgeous apparel of the external world, just as--many will remember--she delighted in bright textures and vivid colours for feminine adornment." Kate Field said:

The inmate of this villa was a little lady with blue-black and sparkling jet eyes, a writer whose dawn is one of promise, a chosen friend of the noblest and best; and on her terrace the Brownings, Walter Savage Landor, and many choice spirits have sipped tea, while their eyes drank such a vision of beauty as Nature and Art have never equalled elsewhere. There was a great love story. Because she was Anglo-Indian or part Jewish, no one knew quite what, it was not acceptable for her to marry Lord Lytton, whose life she had saved through her careful nursing. A relative later wrote: " Romeo-like he arrived at Florence, sighing for Rosaline, and almost immediately met his Juliet. Barriers more impassable than the feuds of Montagues and Capulets prevented any happy issue to this new attachment, but it profoundly affected many years of his life, and coloured all his early writings." The Brownings hoped they would marry. Anna Jameson's letter, July 25, 1857, describes them: Last night after sunset I went up to the villa on Bellosguardo belonging to an English lady (Miss Blagden). The Brownings, Mr. Bulwer Lytton (a son of Sir Edward) and myself formed the party. We sat on a Balcony, with the starry night above our heads and Florence spread in the valley at our feet. Mr. Lytton read us with a charming voice and expression some of his own poems of great beauty and originality. The scene was very striking on the whole and in itself poetical.

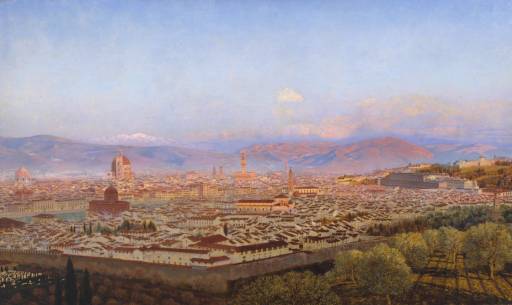

In Elizabeth Browning's words: ' On April 6 [1857] we had tea out of doors on the terrace of our friend Miss Blagden, in her villa up at Bellosguardo, not exactly Aurora Leigh's, mind). You seemed to be lifted up above the world in a divine ecstacy. Oh, what a vision!'

Henry James talked with her one morning at Bellosguardo:

I feel again the sun of Florence in the morning walk out of Porta Romana and up the long winding hill; I catch again, in the great softness, the 'accent' of the straight black cypresses; I love myself again in the sense of the large, cool villa, already then a centre of histories, memories, echoes, all generations deep; I face the Val'd'Arno, vast and delicate, as if it were a painted picture; in especial I talk with an eager little lady, who has gentle gay black eyes and whose type gives, visibly enough, the hint of East-Indian blood. The villa had, as I say, a past then, and has much more of one now; which romantic actualities and possibilities, a crowd of international relations, hung about us as we lingered and talked, making . . . a mere fond fable of lives led and words done and troubles suffered there.

Among the manuscripts in the Armstrong Browning Library are Isa Blagden's verses 'On the Italian colors being replaced on the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, April 27th, 1859'.

O'er the old tower, like red flame curled

Which leapeth sudden to the sky

Its emblem hues all wide unfurled

Upsprings the flag of Italy

2

Its emblem hues! the brave blood shed

The true life blood by heroes given,

The green palms of the martyred dead,

The snowy robes they wear in Heaven.

7

My Florence, which so fair doth be

A dream of beauty at my feet

While smiles above that dappled sky

While glows around that rip'ning wheat

8

As fair, as peaceful and as bright

Art thou as she we hear came down

From Heaven in bridal robes of light

Thy new Jerusalem St. John!

Isa was present at the entombment of Italy's hopes of liberty and unity at the close of one decade, and at their glorious and final resurrection towards the close of the next. She even lived to see Rome delivered, and raised to its proper dignity as the capital of the new Kingdom. As her poems testify, she took the warmest interest in the fortunes of the beautiful and now prosperous land. Signora Villari, the wife of the great historian Pasquale Villari, was by her bedside when she died, January 20, 1873. She is buried in the ' English Cemetery ' in Piazzale Donatello, near Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb.

Mary Somerville

Jessie White Mario

** **essie White ' is a great woman to whom we Italians owe a lot' Giosu� Carducci said. She had met Garibaldi in London in 1854, when he was more or less engaged to be married to an Englishwoman. As this lady's friend she had come to Italy to rejoin the General. Garibaldi valued her masculine energy and her gifts as a medically trained nurse. She was a most fervent disciple of Mazzini who held her in high esteem. Even before meeting him Miss White had been fired with his theories, and once she had met him, she threw herself into the cause with such passion that the apostle himself was frightened. 'Good and devoted as she is, Jessie infuriates me. She talks like a soldier; she insults everyone; she uses a dictatorial manner which is more imperious than Garibaldi's own.'

**essie White ' is a great woman to whom we Italians owe a lot' Giosu� Carducci said. She had met Garibaldi in London in 1854, when he was more or less engaged to be married to an Englishwoman. As this lady's friend she had come to Italy to rejoin the General. Garibaldi valued her masculine energy and her gifts as a medically trained nurse. She was a most fervent disciple of Mazzini who held her in high esteem. Even before meeting him Miss White had been fired with his theories, and once she had met him, she threw herself into the cause with such passion that the apostle himself was frightened. 'Good and devoted as she is, Jessie infuriates me. She talks like a soldier; she insults everyone; she uses a dictatorial manner which is more imperious than Garibaldi's own.'

Jessie White arrived in Genoa in 1857 to take part in the Mazzinian rising for which she had collected considerable funds, but she was promptly arrested and kept in jail for four months. In prison she made the acquaintance of Alberto Mario, an exceedingly handsome young patriot who shared her views. From that moment, the heart of Jessie White nursed not only a fraternal friendship for Garibaldi and a disciple's cult for Mazzini, but a flaming woman's passion for Mario, whose wife she soon became, and with whom she pursued her devoted service to the cause of her adopted country. After 1860, along with her husband, she followed Garibaldi on the field of battle in all his campaigns, and was always in the thick of the fight as an heroic nurse. Miss Henrietta Corkran gave a portrait of Jessie White:

Amongst all the folk who were received in my mother's Paris salon none made a queerer impression on me than Jessie White. She was an English governess when I first caught a glimpse of her. She had very red hair, an extremely animated face, and a peculiarly excitable manner. She often sat cross-legged on the sofa, declaring that tyrants ought to be suppressed. As I was still a child she frightened me. She looked so wild that somehow I connected her with the devil, and could not conceive why my mother and kindly father received so extraordinary a woman. One evening my mother gave a soir�e; Jessie White appeared with an Italian flag in her hand and ribbons of Italian colours round her red hair. She looked like a haystack on fire. She became an intimate friend of General Garibaldi, and so came in contact with Mazzini and Orsini and other Republican leaders. She was the enthusiastic ally of Garibaldi in the Italian War to shake off the Austrian yoke, and distinguished herself greatly as a kind of aide-de-camp to the General in many of the engagements. She was thrown into prison upon a charge of which she was ultimately acquitted. She then married Mario, an aide-de-camp of Garibaldi. Jessie Mario also accompanied the General in his expedition across Sicily and Rome. She nursed the wounded soldiers in the hospitals; they were devotedly grateful to her, and always spoke of her as an angel.

Though they were friends, inevitably things moved towards open disagreement between the invalid Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the robust Jessie White Mario. In fact when Mrs Mario went to America to give a series of propaganda talks and used the name of the Brownings as a recommendation for the cause they were horrified lest they be taken as patrons of revolutionary ideas, and they issued a denial in an American newspaper. Polemical correspondence ensued in the columns of theAthenaeum, which ended with a letter from the Browning stating that ' despite our high esteem and personal affection' for Jessie Mario, there was diversity in their political opinions. They became reconciled later, but when Elizabeth heard of the arrest of Jessie and of her expulsion to Switzerland, she did not conceal a certain feeling of relief.

Thomas Adolphus Trollope said of Jessie White:

She has published a large life of Garibaldi, which is far and away the best and most trustworthy account of the man and his wonderful works. She is not blind to the spots on the sun of her adoration, nor does she seek to conceal the fact that there were such spots, but she is a true and loyal worshipper all the same. In the last years of her life, widowed and much impoverished, she supported herself with dignity by teaching in Italian secondary schools and by writing a history of the events she had taken part in. To the end dressed in her Garibaldi red shirt.

Anita Garibaldi

** **nita, Garibaldi's tiny, determined wife, had met him in Latin America, and joined him through terrible times, being pregnant with their child at the Fall of the Roman Republic in 1849. Margaret Fuller describes that Fall of Mazzini's Roman Republic to the French:

**nita, Garibaldi's tiny, determined wife, had met him in Latin America, and joined him through terrible times, being pregnant with their child at the Fall of the Roman Republic in 1849. Margaret Fuller describes that Fall of Mazzini's Roman Republic to the French:

In the evening 't is pretty though terrible, to see the bombs, fiery meteors, springing from the horizion line upon their bright path, to do their wicked message. 'Twoud not be so bad, methinks, to die by one of these, as wait to have every drop of pure blook, every childlike radiant hope, drained and driven from the heart by the betrayals of nations and of individuals, till at last the sickened eyes refuse more to open to that light which shines daily on such pits of iniquity.

. . . all are light, atheletic, resolute figures, many of the forms of the finest manly beauty of the South, all sparkling with its genius and ennobled by the resolute spirit, ready to dare, to do, to die. We followed them to the piazza of St. John Lateran. never have I seen a sight so beautiful, so romantic, and so sad. Whoever knows Rome knows the peculiar solemn grandeur of that piazza, scene of the first triumph of the Rienzi, and whence may be seen the magnificence of the "mother of all churches," . . . The sun was setting, the crescent moon rising, the flower of the Italian youth were marshalling in that solemn place. They had been driven from every other spot where they had offered their hearts as bulwarks of Italian independence.

. . They had all put on the beautiful dress of the Garibaldi legion, the tunic of bright red cloth, the Greek cap, or else round hat with Puritan plume. Their long hair was blown back from reslute faces; all looked full of courage. . . I saw the wounded, all that could go, laden upon their baggage cars; some were already pale and fainting, still they wished to go. . . The wife of Garibaldi followed him on horseback. He himself was distinguished by the white tunic; his look was entirely that of a hero of the Middle Ages,--his face still young, for the excitements of his life, though so many, have all been youthful, and there is no fatigue upon his brow or cheek . . . And Rome! Must she lost also these beautiful and brave, that promised her regeneration, and would have given it, but for the perfidy, the overpowering force, of the foreign intervention?

Anita Garibaldi died in childbirth during that flight, the two corpses being buried hurriedly in shallow sand, so that dogs dug them up again.

Cristina Trivulzio, Princess Belgioioso

** **argaret Fuller, writing from Italy to America, described the hospital work being done by Jessie White Mario and by Cristina Trivulzio, the Princess Belgioioso.

**argaret Fuller, writing from Italy to America, described the hospital work being done by Jessie White Mario and by Cristina Trivulzio, the Princess Belgioioso.

Then I have, for the first time, seen what wounded men suffer. The night of the 30th of April I passed in the hospital and saw the terrible agonies of those dying or who needed amputation, felt their mental pains and longing for the loved ones who were away. . .

But . . . the hospitals: these were put in order, and have been kept so, by the Princess Belgioioso. The princess was born of one of the noblest families of the Milanese, a descendant of the great Trivalzio, and inherited a large fortune. Very early she compromised it in liberal movements, and, on their failure, was obliged to fly to Paris, where for a time she maintained herself by writing, and I think by painting also. A princess so placed naturally excited great interest, and she drew around her a little court of celebrated men.

After recovering her fortune, she still lived in Paris, distinguished for her talents and munificence, both toward literary men and her exiled countrymen. Later, on her estate, called Locate, between Pavia and Milan, she had made experiments in the Socialist direction with fine judgement and success. Association for education, for labor, for transaction of household affairs, had been carried on for several years; she had spared no devotion of time and money to this object, loved, and was much beloved by, those objects of her care, and said she hoped to die there. All is now despoiled and broken up, though it may be hoped that some seeds of peaceful reform have been sown which will spring to light when least expected.

From Milan she went to France, but, finding it impossible to effect anything serious there in behalf of Italy, returned, and has been in Rome about two months. Since leaving Milan she receives no incomes, her possessions being in the grasp of Radetzky, and cannot know when, if ever, she will again. But as she worked so largely and well with money, so can she without. She published an invitation to the Roman women to make lint and bandages, and offer their services to the wounded; she put the hospitals in order; in the central one, Trinita de' Pellegrini, once the abode where the pilgrims were received during Holyweek, and where foreigners were entertained by seeing their feet washed by the noble dames and dignatories of Rome, she has remained day and night since the 30th of April, when the wounded were first there. Some money she procured at first by going through Rome, accompanied by two other ladies veiled, to beg it. Afterward the voluntary contributions were generous.

Sarah Parker Remond

he anti- slavery lecturer Sarah Parker Remond had three goals in mind when she first sailed from Boston for Liverpool in September of 1858. One was to remove herself from the daily toxicity of American racism. Another was to do all she could to consolidate anti-slavery sentiment on the eve of the Civil War by arguing the ethical and economic advantages of British support for the Union during the War. The third was to secure for herself an education superior to any available to her at home. Her speaking schedule, before groups up to two thousand strong, kept her on the road and often near exhaustion. Still, she wrote to Maria Weston Chapman that, 'on the 12th of this month [October 1859] I go to London to attend the lectures at the Ladies College.' She continued both her lectures and her studies at Bedford College for Ladies, later a part of the University of London. Although there was steady demand for her services following the war as a speaker on behalf of the freedmen, Remond had her eye on Italy.

he anti- slavery lecturer Sarah Parker Remond had three goals in mind when she first sailed from Boston for Liverpool in September of 1858. One was to remove herself from the daily toxicity of American racism. Another was to do all she could to consolidate anti-slavery sentiment on the eve of the Civil War by arguing the ethical and economic advantages of British support for the Union during the War. The third was to secure for herself an education superior to any available to her at home. Her speaking schedule, before groups up to two thousand strong, kept her on the road and often near exhaustion. Still, she wrote to Maria Weston Chapman that, 'on the 12th of this month [October 1859] I go to London to attend the lectures at the Ladies College.' She continued both her lectures and her studies at Bedford College for Ladies, later a part of the University of London. Although there was steady demand for her services following the war as a speaker on behalf of the freedmen, Remond had her eye on Italy.

Sarah Remond�s political connections in England introduced her to reformers and revolutionaries from the Continent. With her friends Harriet Martineau, Mary Estlin and Clementia Taylor, she was a founding member of the Ladies� London Emancipation Society which supported causes beyond the abolition of slavery in the United States. The Society had two male members, one active, and one honorary. The active member was Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini whom Remond had met in her early days abroad. He was a close friend of the Taylors with whom she stayed in London. Remond, as did Margaret Fuller before her, became a supporter of the Italian reunification struggle. She won Mazzini�s confidence as an effective speaker and fund-raiser for his cause during his visits with the Taylors. The honorary member was the great Garibaldi himself.

Sarah Parker Remond, collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

At the age of forty Sarah Parker Remond moved to Florence where she embarked on medical studies at Santa Maria Nuova, the hospital founded in the thirteenth century by Dante's Beatrice's father and which served as Florence Nightingale's model of medical care and training.

The black publication, The Christian Recorder, reported on what was probably one stage of her medical education with the notice that, 'Miss Sarah Remond, a gifted colored lady, who studied medicine with Dr. Appleton --the friend and physician of Theodore Parker, during the latter portion of his life at Rome and Florence, has been regularly admitted as a practitioner of midwifery in Florence, where she is now residing, with excellent prospects of employment and success. Her merit has won her friends on the continent of Europe, as it did in England. On going to Italy, she had excellent letters of introduction from Mazzini, among others. With this satisfactory passport, Dr. Appleton went with her to call on Garibaldi, and, though many others were waiting for an interview, they were instantly admitted. Miss Remond is not only well received everywhere in Florence, but she has friends among the very best people there.'

A few years later, Sarah Remond�s sister, Caroline Putnam, an Oberlin College graduate and founder of a school for freed men and women in Lottsburg, Virginia, lived with her for a while in Florence. Putnam�s school was supported by Louisa May Alcott (senior) and Ellen Emerson. Elizabeth Buffum Chace, human rights activist and former conductor on the Underground Railroad, visited Remond in Florence in 1873 and wrote that: 'Sarah Remond is a remarkable woman and by indomitable energy and perseverance is winning a fine position in Florence as a physician and also socially; although she says Americans have used their influence to prevent her by bringing their hateful prejudices over here. If one tenth of the American women who travel in Europe were as noble and elegant as she is we shouldn�t have to blush for our country women as often as we do.'

Sarah Parker Remond certainly aroused curiosity and comment in Florence, but the city had a particular sophistication about race unusual on the Continent. After all, the fabled dynasty of the Medici displayed the likeness of Alessandro, the first Duke of Florence, born of a union between a slave of African origin named Simonetta, and, it appears, the future Pope Clement VII. Alessandro lies buried in the tomb of Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino sculpted by Michelangelo, with its spectacular figures of Dusk and Dawn.

Jacopo Pontormo, Alessandro de Medici, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Decades after Sarah Parker Remond's arrival, Frederick Douglass and his second wife, Helen, visited Florence 10 May 1887. Douglass went straight from breakfast to the 'English' Cemetery to visit the tomb of Elizabeth Barrett Browning honouring her poetry against slavery and to stand, lost in reverie, at the grave of the abolitionist clergyman Theodore Parker. Parker, during his final illness, refused to die, if die he must, in Papal Rome. He longed for Boston but knew he would never survive the journey home and so, announcing that 'I will not die on this accursed soil, I will not leave my bones in this detested soil,' insisted on being lifted from his deathbed and transported by carriage to Florence. The real Theodore Parker, he told his friends, was in America; this was just a dying man they saw before them. The remarks of his final day included the wish to walk once more on Boston Common. If he could not die in Boston, Florence, the Boston of Italy, was his chosen resting place.

[Marilyn Richardson]Rosa and Francesco Madiai

The tombs of Arnold Savage Landor with its extroardinary statue of Julia Savage Landor, Walter Savage Landor's estranged wife, and that of Rosa Madiai lie side by side in the Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery. Julia Savage Landor's is grandiloquent in its hypocritical mourning. She, the daughter of a bankrupt Swiss banker, had thrown her poet husband out of their villa he had given them in San Domenico, leaving him to roam the streets of Florence penniless, until the Brownings arranged for him to lodge with their maid, Lily Wilson, in Via della Chiesa. Lily had been the witness to the Brownings' marriage and the companion to their elopement.

While Rosa's tomb is crude but eloquent in a different manner, giving Mary's 'Magnificat' of humility.

*� ROSA MADIAI PULINI/ ITALIA/ Madiai/ Rosa/ / Italia/ Firenze/ 28 Marzo/ 1871/ / 1124/+/ Rosa Madiai, Rome/ Walter Savage Landor, 'The Archbishop of Forence and Francesco Madiai', Imaginary Conversations/ Giuliana Artom Treves, Golden Ring , pp. 196-99/ ROSA/ PULINI/ NEI MADIAI/ L'ANIMA MIA MAGNIFICA IL SIGNORE E LO SPIRITO/ MIO . . . ESTEGGIA IN DIO MIO SALVATORE/ . . . / CREDETTI IL VANGELO/ PATII IL MONDO TRISTO/ SON ORA NEL CIELO/ RISIEDO CON CRISTO/ A5T(70)

Francesco e Rosa Madiai

ROSA MADIAI PULLINI (+1871), a woman of the people, of modest condition, she and her husband found themselves at the centre of an international dispute: a public commission of inquiry, diplomatic intervention from all over Europe, biographies and newspaper articles. The Madiais, converted to Protestantism like Count Guicciardini, were sentenced to prison, but the sentence was commuted to exile because of the tremendous reaction created by the severity of the sentence. Exiled to Nice, they returned to Florence in 1859 to end their days in a modest little lodging in Piazza del Carmine. Rosa's grave is near those of other witnesses to the dawn of the Florentine Evangelical movement. LS

Coincidentally, Walter Savage Landor's final Imaginary Conversation XL is the 'Archbishop of Florence and Francesco Madiai' and part of that campaign, particularly carried on in English, to free the Madiai from the injustice of their prison sentence.

Archbishop. It grieves my heart, O unfortunate man! to find you reduced to this condition.

Francesco Madiai. Pity it is, my Lord, that so generous a heart should be grieved by any thing.

Archbishop. Spoken like a Christian! There are then some remains of faith and charity left within you!

Francesco Madiai. Of faith, my Lord, there are only the roots, such as have often penetrated ere now the prison-floor. Charity too is among those plants which, although they thrive best under the genial warmth of heaven, do not wither and weaken and died down deprived of air and sunshine. I might never had thought seriously of praying for my enemies, had it not been the will of a merciful and all-wise God to cast me into the middle of them.

Archbishop. From these, whom you rashly call enemies, you possess the power of delivering yourself. Confess your crime.

Francesco Madiai. I know the accusation; not the crime.

Archbishop. Disobedience to the doctrines of the Church.

Francesco Madiai. I am so ignorant, my Lord, as never to have known a tenth or twentieth part of its doctrines. But by God's grace I know and understand the few and simple ones which His blessed Son taught us.

Archbishop. Ignorant as you acknowledge yourself to be, do you presume that you are able to interpret them?

Francesco Madiai. No, my Lord. He has done that Himself, and intelligibly to all mankind.

Archbishop. By whose authority did you read and expound the Bible?

Francesco Madiai. By His.

Archbishop. By His? To thee?

Francesco Madiai. What he commanded the Apostles to do, and what they did, surely is no impiety.

Archbishop. It may be.

Francesco Madiai. Our Lord commanded His Apostles to go forth and preach the gospel to all nations.

Archbishop. Are you an Apostle, vain, foolish man?

Francesco Madiai. Alas! my Lord, how far, how very far, from the least of them! But surely I may follow where they lead; and I am more likely to follow them in the right road, if I listen to no directions from others far behind.

Archbishop. Go on, go on, self-willed creature! doomed to perdition.

Francesco Madiai. I have ventured to repeat the ordinances of Christ and the Apostles; no more. I have nothing to add, nothing to interpret.

Archbishop. I shall look into the matter; I doubt whether He ever gave them such an ordinance - I mean in such a sense - for I remember a passage that may lead astray the unwary. Any thing more?

Francesco Madiai. My Lord, there is also another.

Archbishop. What is that?

Francesco Madiai. "Seek truth, and ensue it".

Archbishop. There is only one who can tell us, of a surety, what truth is; namely, our Holy Father.

Francesco Madiai. Yes, my Lord, of this I am convinced.

Archbishop. Avow it then openly, and you are free at once.

Francesco Madiai. Openly, most openly, do I, and have I, and ever will I avow it. Permit me, my Lord Archbishop, to repeat the blessed words, which have fallen from your Lordship; "There is only one who can tell us of a certainty what truth is". - "our Holy Father", - our Father which is in Heaven.

Archbishop. Scoffer! heretic! infidel! No, I am not angry; not in the least: but I am hurt, wounded, wounded deeply. It becomes not me to hold a longer conference with one so obstinate and obdurate. A lower order in the priesthood has this duty to perform.

Francesco Madiai. My Lord, you have conferred, I must acknowledge, an unmerited distinction upon one so humble and so abject as I am. Well am I aware that men of a lower order are the more proper men to instruct me. They have taken that trouble with me and thousands more.

Archbishop. Indeed! indeed! so many? His Imperial Highness, well-informed, as we thought, of what passes in every house, from the cellar to the bed-chamber, had no intelligence or notion of this. Denounce the culpable, and merit his pardon, his protection, his favor. Do not beat your breast, but clear it. Give me at once the names of these teachers, these listeners; I will intercede in their behalf.

Francesco Madiai. The name of the first and highest was written on the cross in Calvary; poor fishermen were others on the sea of Galilee. I could not enumerate the listeners; but the foremost rest, some venerated, some forgotten, in the catacombs of Rome.

Archbishop. Francesco Madiai! there are yet remaining in you certain faint traces of the Church in her state of tribulation, of the blessed saints and martyrs in the catacombs. But, coming near home, Madiai, you have a wife, aged and infirm; would not you help her?

Francesco Madiai. God will; I am forbidden.

Archbishop. It is more profitable to strive than to sigh. I pity your distress; let me carry to her an order for her liberation.

Francesco Madiai. Your Lordship can.

Archbishop. Not without your signature.

Francesco Madiai. The cock may crow ten times, ten mornings, ten years before I deny my Christ. O wife of my early love, persevere, persevere.

Archbishop. This to me?

Francesco Madiai. No, my Lord! but to a martyr; from one unworthy of that glory; in the presence of Him who was merciful and found no mercy - my crucified Redeemer.

Archbishop. After much perseverance, I declare to you, with all the frankness of my character, there is no prospect of your liberation.

Francesco Madiai. Adieu, adieu, O Rosa! Light and enlivener of my earlier days, solace and support of my declining! We must now love God alone, from God alone hope succor. We are chastened but to heal our infirmities; we are separated but to meet inseparably. To the constant and resigned there is always an Angel that opens the prison-door; we wrong him when we call him Death.

It is fitting that the tombs of Walter Savage Landor and Rosa Madiai should rest in the same Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery, along with that of the Contessa Giulia Guicciardini, whose brother Pietro died in exile.

Julia Savage Landor's tomb, instead, is in the Cemetery of the Allori near Galluzzo.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

** **arriet Beecher Stowe, the apostle of freedom for the slaves, came to Florence in 1857. The fabulous success on two continents of Uncle Tom's Cabin assured her an enthusiastic reception in Italy also. "We find her reading Madame de Sta�l, and especially Corinne, with eager delight. In Rome one day she visited the workshop of the brothers Castellani, patriots and goldsmiths, and admired the exquisite workmanship of their jewelry. Castellani handed her the head of an Egyptian slave chiselled in black onyx saying:

**arriet Beecher Stowe, the apostle of freedom for the slaves, came to Florence in 1857. The fabulous success on two continents of Uncle Tom's Cabin assured her an enthusiastic reception in Italy also. "We find her reading Madame de Sta�l, and especially Corinne, with eager delight. In Rome one day she visited the workshop of the brothers Castellani, patriots and goldsmiths, and admired the exquisite workmanship of their jewelry. Castellani handed her the head of an Egyptian slave chiselled in black onyx saying:

'Madam, we know what you have been to the poor slaves. We ourselves are but poor slaves still in Italy; You feel for us; Will you keep this gem as a slight recognition for what you have done?' She took the jewel in silence; but when we looked for some response, her eyes were filled with tears; and it was impossible for her to speak. Mrs. Stowe moved in such an aura of fame that the Brownings awaited her arrival with some misgiving. But they were quite won over by her simplicity and earnestness. ' I, the author of Uncle Tom's Cabin? No, indeed! The Lord Himself wrote it, and I was but the humblest instrument in his hand. To Him alone be all the praise.'

Margaret Fuller

" agnificent, prophetic, this new Corinne. She never confounded relations; but kept a hundred fine threads in her hand, without crossing or entangling any." So wrote Emerson on of New England's Margaret Fuller. Born in 1810, her tragic death by drowning occurred 16 July 1850. At age of six Margaret read Latin as well as English and soon after Greek, at 15 revelling in Madame de Sta�l and Petrarch.

agnificent, prophetic, this new Corinne. She never confounded relations; but kept a hundred fine threads in her hand, without crossing or entangling any." So wrote Emerson on of New England's Margaret Fuller. Born in 1810, her tragic death by drowning occurred 16 July 1850. At age of six Margaret read Latin as well as English and soon after Greek, at 15 revelling in Madame de Sta�l and Petrarch.

She travelled to Italy as a journalist, already deeply committed to women's position.

. . . A woman should love Bologna, for there has the spark of intellect in woman been cherished with reverent care. . . they proudly show the monument to Matilda Tambroni, late Greek Professor there. . . In their anatomical hall is the bust of a woman, Professor of Anatomy. In Art they have had Properzia di Rossi, Elizabetta Sirani, Lavinia Fontana, and delight to give their works a conspicuous place. . . In Milan, also, I see in the Ambrosian Library the bust of a female mathematician. These things make me feel that, if the state of woman in Italy is so depressed, yet a good-will toward a better is not wholly wanting. She mentions Adam Mickiewicz's presence and gives their declaration of faith "Every one of the nations a citizen,-every citizen equal in rights and before authorities. To the Jew, our elder brother, respect, brotherhood, aid on the way to his eternal and terrestrial good, entire equality in political and civil rights. To the companion of life, woman, citizenship, entire equality of rights." In Florence he was addressed as the "Dante of Poland ."

Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote that

Madame d'Ossoli (calling her by her supposed husband's name) was a most interesting woman to me, though I did not sympathize with a large portion of her opinions. Her written words are just naught. She said herself they were sketches, thrown out in haste and for the means of subsistence, and that the sole production of hers which was likely to represent her at all, would be the history of the Italian Revolution. In fact, her reputation, such as it was in America, seemed to stand mainly on her conversation and oral lectures. If I wished any one to do her justice I should say, as I have indeed said, 'Never read what she has written.' The letters, however, are individual, and full, I should fancy of that magnetic personal influence which was so strong in her. I felt drawn toward her during our intercourse; I loved her, and the circumstances of her death shook me to the very roots of my heart. The comfort is that she lost little in this world; the change could not be loss to her. She had suffered, and was likely to suffer more. The American Consul spoke of her work in the Roman Republic's Hospitals. Miss Fuller took an active part in this noble work, and the greater portion of her time, during the entire seige, was passed in the Hospital of the Trinity of the Pilgrims, which was placed under her direction, in attendance upon its inmates.

The weather was intensely hot; her health was feeble and delicate; the dead and dying were around her in every form of pain and horror; but she never shrank from the duty she had assumed. Her heart and soul were in the cause for which these men had fought, and all was done that a woman dould do to comfort them in their sufferings. I have seen the eyes of the dying, as she moved among them, extended upon opposite beds, meet in commendation of her unwearied kindness; and the friends of those who tehn passed away may derive consolation from the assurance that nothing of tenderness and attention was wanting to soothe their last moments. And I have hear many of those who recovered speak with all the passionate fervor of the Italian nature of her, whose sympathy and compassion throughout their long illness fulfilled all the offices of love and affection. Mazzini, the chief of the Triumvirate,-who, better than any man in Rome, knew her worth,-often expressed to me his admiration of her high character; and the Princess Belgioioso, to whom was assigned the charge of the Papal Palace on the Quirinal, which was converted on this occasion into a hospital, was enthusiastic in her praise. And in a letter which I received not long since from this lady, who is gaining the bread of an exile by teaching languages in Constantinople, she alludes with much feeling to the support afforded by Miss Fuller to the Republican party in Italy. Here, in Rome, she is still spoken of in terms of regard and endearment; and the announcement of her death was received with a degree of sorrow which is not often bestowed upon a foreigner, and especially one of a different faith.

She informed me that she had sent for me to place in my hands a packet of important papers, which she wished me to keep for the present, and, in the event of her death, to transmit it to her friends in the United States. She then stated that she was married to the Marquis Ossoli, who was in command of a battery on the Pincian Hill. . . The packet which she placed in my possession, contained, she said, the certificates of her marriage, and of the birth and baptism of her child. . .

On the same day the French army entered Rome, and, the gates being opened, Madame Ossoli, accompanied by the Marquis, immediately proceeded to Rieti, a village lying at the base of the Abruzzi Mountains, where she had left her child in the charge of a confidential nurse, formerly in the service of the Ossoli family. She remained, as you are no doubt aware, some months at Rieti, whence she removed to Florence, where she resided until her ill-fated departure for the United States. During this period I received several letters from her, all of which, though reluctant to part with them, I inclose to your address, in compliance with your request.

There are two sculptures which particularly inspired women in the nineteenth century.

One is Michelangelo's 'Aurora' from the Medici Tomb in the New Sacristy at San Lorenzo. The Republic of Florence commissioned these sculptures. Later Michelangelo wrote a poem for Dawn to speak in which she desires not to awake while the Medici have robbed Florence of her freedom. Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote about it at length in Casa Guidi Windows and used it for the title of her epic poem, Aurora Leigh.

The other is Hiram Powers' 'Greek Slave'. It appears to be about the War of Greek Independence, in whose cause Lord Byron fought and died. But it is really about Hiram Powers' own knowledge of himself as both American and Native American, and about Italy, which in this period was ground under by Austria, Spain, France and the Pope, as had Greece been by Turkey. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who was Hiram Powers' great friend and admirer, spoke of him as part Native American. Another sculpture of his is 'The Last of her Tribe', in which an Indian maiden is fleeing from her persecutors. It is exquisite. Elizabeth wrote a powerful sonnet about the 'Greek Slave', which Queen Victoria read. The Queen also saw the sculpture for it was at the centre of the Great Crystal Palace Exhibition she visited, leaning upon her Prince Consort's arm. Margaret Fuller had written:

You seem as crazy about Powers's Greek Slave as the Florentines were about Cimabue's Madonnas, in which we still see the spark of genius, but not fanned to its full flame. . . I consider the Slave as a form of simple and sweet beauty, but that neither as an ideal expression nor a specimen of plastic power is it transcendent. . . To me, his conception of subject is not striking: I do not consider him rich in artistic thought'. She prefers his busts. But she had also written approvingly: 'As to the Eve and the Greek Slave, I could only join with the rest of the world in admiration of their beauty and the fine feeling of nature which they exhibit. The statue of Calhoun is full of power, simple, and majestic in attitude and expressions.'

Hiram Powers' 'Greek Slave' is normal in its proportions. But Hiram Powers also sculpted colossal statues, as did similarly the tiny Harriet Hosmer. One gigantic statue of Calhoun by Powers was shipwrecked, if indeed it did not cause the wreck of the ship on which the Fuller-Ossoli family perished; one marble effigy of a statesman never reached America, another ended at the bottom of the Bay of Biscay.

Madame Ossoli writes to Marchioness Visconti Arconati

I am absurdly fearful about this voyage. Various little omens have combined to give me a dark feeling. Among others, just now we hear of the wreck of the Westmoreland bearing Power's 'Eve."

Just before Margaret sailed Mrs. Browning wrote of their last evening in Florence: The conversation lapsed into a somewhat gloomy and foreboding tone. The Marchese recalled, half-jestingly, an old prophecy made to him when a boy that the sea was hostile to him and that he had been warned never to embark on a voyage. To Miss Mitford EBB wrote: Such gloom had Madame d'Ossoli in leaving Italy! She was full of sad presentiment. Do you know she had her little son give a small Bible as a parting gift to Penini, writing in it, 'In memory of Angelo d'Ossoli,'- a strange, propetic expression. Pen showed this Bible to Lillian Whiting:.

Angiolino was nourished by means of a goat on shipboard, there being no refrigeration for the Victorian sea voyage. Small pox broke out, Angiolino miraculously recovering, but the Captain died. The first mate failed in navigating the ship and it wrecked off Fire Island. "Neither Margaret's body, nor that of her husband was ever recovered; that of little Angelo was borne through the breakers by a sailor and laid lifeless on the sands. The manuscript of her "History of Italy" was lost in the wreck." The still warm bodies of steward and child and trunk with letters beween her husband and herself were all that survived.

It was this drowning of her friend, in a ship named the `Elizabeth', that paradoxically released Elizabeth to write Aurora Leigh, whose two heroines she models upon Margaret Fuller and upon herself as gypsy.

Harriet Hosmer

** **arriet Hosmer initially studied anatomy in St Louis, though as a woman she was not permitted to attend medical school, coming to Rome from Boston when she was 22. She became the pupil of John Gibson, who in turn was the pupil of Canova, and she "used to ride out along through the streets of Rome, her short brown curls cut like a boy's, gathered under a little velvet capt, and her hands deep in the pockets of a velvet jacket, to the astonishment and fascination of everyone'. 'A slight, delicate, though well-rounded figure, a forehead "royal with truth," short curling hair and rosy, smiling cheeks, not to speak of the "dimples" that Mrs. Browning loved in her "Hattie," made up a buoyant and magnetic personality." Brownings write to her lovingly, mentioning her Greek studies.

**arriet Hosmer initially studied anatomy in St Louis, though as a woman she was not permitted to attend medical school, coming to Rome from Boston when she was 22. She became the pupil of John Gibson, who in turn was the pupil of Canova, and she "used to ride out along through the streets of Rome, her short brown curls cut like a boy's, gathered under a little velvet capt, and her hands deep in the pockets of a velvet jacket, to the astonishment and fascination of everyone'. 'A slight, delicate, though well-rounded figure, a forehead "royal with truth," short curling hair and rosy, smiling cheeks, not to speak of the "dimples" that Mrs. Browning loved in her "Hattie," made up a buoyant and magnetic personality." Brownings write to her lovingly, mentioning her Greek studies.

In the winter of 1853 she sculpted the clasped hands of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning.

There are photographs of Hattie in short skirts on steps working on male statue three times her size, then of her sculpture of 'Beatrice Cenci', which was exhibited in the Royal Academy, 1857. That sculpture shows Beatrice Cenci, the night before her execution, asleep in her Castel Sant'Angelo cell. Harriet Hosmer, like the Pre-Raphaelite Brethren before her, is likely influenced by Anna Jameson.

She wrote of her studies for her sculpture of Zenobia:

When I was in Florence I searched in the Pitti and the Magliabechian libraries for costumes and hints . . . Prof Nigliarini told me that if I copied the dress and ornaments of the Madonna in the old mosaic of San Marco, it would be the very thing, as she is represented in Oriental regal costume. I went to look and found it. The model is invaluable, requiring little change save a large mantle thrown over it all. The ornaments are quite the thing, very rich and Eastern, with just such a girdle as is described in Vopiscus.

The 'Zenobia' was famous, and exhibited in London in an octagonal temple, Charles Sumner said "It lives and moves with the solemn grace of a dethroned queen." It is now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. For the London Exhibition the Prince of Wales also loaned 'Puck', described as ' a laugh in marble', and Lady Marian Alford, 'Medusa'. The 'Sleeping Faun' was shown in Dublin. Harriet moved to the Palazzo Barberini, where she created a companion 'Waking Faun', now being 36. Much later Lillian Whiting describes her, in Chicago, reading from Browning's letters to her, then bursting into tears soon before 1908. When she died at 78, she was still planning projects that would take yet another lifetime.

F�licie de Fauveau

he sculptress F�licie de Fauveau was no lover of the Risorgimento but a French Royalist, having to live in exile in Florence because of her politics, following even imprisonment in France. She was much admired by Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Isa Blagden, the latter writing a fine essay on her, worthy of being read here.

he sculptress F�licie de Fauveau was no lover of the Risorgimento but a French Royalist, having to live in exile in Florence because of her politics, following even imprisonment in France. She was much admired by Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Isa Blagden, the latter writing a fine essay on her, worthy of being read here.

Lily Wilson

n Elizabeth Barrett Browning's day and in her circle were such women as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Harriet Hosmer, Harriet Martineau, Anna Jameson, Cristina Rossetti, Margaret Fuller, Isa Blagden , Princess Belgioioso, Theodosia Garrow Trollope , Jessie White Mario, Anita Garibaldi, and last but not least Elizabeth Wilson without whom Elizabeth could never have come to Italy nor borne the child Pen nor written Aurora Leigh. It was Lily who persuaded Elizabeth to come off laudanum long enough for a successful pregnancy, the child Pen Browning, who was her great joy. I suggested to Margaret Forster the writing of Lady's Maid, and now I wish I could rewrite that book and make it more poetical. Lily Wilson called her two sons, Orestes and Pylades, the classical pair whom Elizabeth, as Electra, had mentioned in her Sonnet V. Elizabeth was very jealous of Wilson and dismissed Lily from her service for her second pregnancy, her two sons having to be raised apart, one in England, one in Italy. When the brothers eventually met neither shared a language with the other. Like Walter Savage Landor and Marian Erle, Elizabeth Wilson, too, was capable of great madness, learning and poetry and did not just have the 'damp housemaid's soul' Forster gives her. Walter Savage Landor was her boarder at a time of his greatest dementia.

n Elizabeth Barrett Browning's day and in her circle were such women as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Harriet Hosmer, Harriet Martineau, Anna Jameson, Cristina Rossetti, Margaret Fuller, Isa Blagden , Princess Belgioioso, Theodosia Garrow Trollope , Jessie White Mario, Anita Garibaldi, and last but not least Elizabeth Wilson without whom Elizabeth could never have come to Italy nor borne the child Pen nor written Aurora Leigh. It was Lily who persuaded Elizabeth to come off laudanum long enough for a successful pregnancy, the child Pen Browning, who was her great joy. I suggested to Margaret Forster the writing of Lady's Maid, and now I wish I could rewrite that book and make it more poetical. Lily Wilson called her two sons, Orestes and Pylades, the classical pair whom Elizabeth, as Electra, had mentioned in her Sonnet V. Elizabeth was very jealous of Wilson and dismissed Lily from her service for her second pregnancy, her two sons having to be raised apart, one in England, one in Italy. When the brothers eventually met neither shared a language with the other. Like Walter Savage Landor and Marian Erle, Elizabeth Wilson, too, was capable of great madness, learning and poetry and did not just have the 'damp housemaid's soul' Forster gives her. Walter Savage Landor was her boarder at a time of his greatest dementia.

Christina Rossetti

** **hristina Rossetti and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were the children of Italian parents, their father, Gabriele Rossetti, being from Naples of illiterate parents but educated at the University of Naples, then as a political exile, being Professor of Italian, at King's College, while their mother was of Tuscan aristocracy. They spoke Italian with their father, English with their mother, whose commonplace book from which she taught them contained Byron and Sappho.

**hristina Rossetti and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were the children of Italian parents, their father, Gabriele Rossetti, being from Naples of illiterate parents but educated at the University of Naples, then as a political exile, being Professor of Italian, at King's College, while their mother was of Tuscan aristocracy. They spoke Italian with their father, English with their mother, whose commonplace book from which she taught them contained Byron and Sappho.

The figures of Dante and Beatrice became for this family the ideal of love between men and women. While the Risorgimento was taking place in Italy, in England we witness the Oxford Movement in religion and the Pre-Raphaelite Movement in art. We could almost say that the Italian Risorgimento was inspired by English-speaking ladies from both sides of the Atlantic while the English Pre-Raphaelite and Oxford Movements were inspired by Englishmen in love with Italy. Dante Gabriel Rossetti sketched Lord Tennyson reading Maud at a dinner party Elizabeth and Robert attended and Elizabeth treasured that sketch, keeping it on the mantle piece at Casa Guidi. But it was Tennyson whom Queen Victoria had had become Poet Laureate in 1850, not Elizabeth.

These women, as poets, writers, journalists, sculptors, and in all but license, doctors, lived in flesh and blood the pages of Madame de Sta�l's Romance, Corinne ou Italie. They similarly understood the language of freedom being spoken in marble by Michelangelo and Hiram Powers, and that spoken in poetry by Sophocles and Byron. Even Elizabeth and Robert's child, Pen, grew up to become a sculptor, studying under Rodin, and sculpting his illegitimate daughter, Ginevra, as this bust of the murdered heroine Pompilia of his father's The Ring and the Book. Ginevra is Elizabeth's granddaughter. Some day I should like to publish a book in Italian on these women (its English title being Laurel Garland: Women of the Risorgimento), awarding a chapter, a laurel leaf, to each of them. These women, gathered from the British Isles, Europe and the Americas, shaped the histories of Florence and Rome, and earned Laura's wreath.

Cameo with Poet's Laurel Garland, Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Tomb

In compiling this lecture/essay I am greatly indebted to the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum, Baylor University, Texas, U.S.A., to the kindness of the Browning Institute's Casa Guidi, 1987-1988, and to Giuliana Artom Treves, The Golden Ring: A Study of Anglo-Italian Relations, to which I now add the contributions by Marilyn Richardson and Silvia Mascalchi.Julia Bolton Holloway.

****FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE � JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN : WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III,IV,V,VI,VII , VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICEAUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,ENGLISH || VITA** New: Opere Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence

****

**** **

**

To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library click on our Aureo Anello Associazione's PayPal button:

THANKYOU!