Kingdoms of the Germanic Tribes (original) (raw)

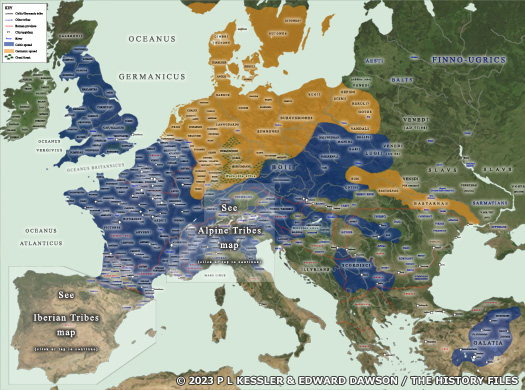

Teutones (Germanics / Celts?) In the first century AD, vast areas of central, northern, andEastern Europe were dark and unknown lands full of savage Germanic barbarians - at least according to the Romans. Little detail is known about many of those savage Germanic barbarians, but brief windows are opened onto their lives and organisation at various points during the existence of the Roman empire in Europe, while other Germanic groups went on to play major roles in the extinction of that empire.  The Indo-European Germanic ethnic group began as a division of the western edge of late proto-Indo-European dialects around 3300 BC. This particular division migrated as part of the Yamnaya horizon to reach the southern coastline of the Early Baltics, seemingly as part of the territorially-extensive Corded Ware culture. From there, over the course of a millennium or more, elements of them entered southern Scandinavia (see feature link for more detail). The Indo-European Germanic ethnic group began as a division of the western edge of late proto-Indo-European dialects around 3300 BC. This particular division migrated as part of the Yamnaya horizon to reach the southern coastline of the Early Baltics, seemingly as part of the territorially-extensive Corded Ware culture. From there, over the course of a millennium or more, elements of them entered southern Scandinavia (see feature link for more detail).  By the time in which Germanic tribes were becoming key players in Western European politics in the last two centuries BC, the previously dominant Celts were on the verge of being conquered by Rome (see map link for general tribal locations). They had already been pushed out of northern and Central Europe by a mass of Germanic tribes which were steadily carving out a new homeland. A large-scale incursion of the sea into Jutland around the period between 120-114 BC is known as the Cimbrian Flood. It permanently altered the shape of the coastline and drastically affected the way people lived in the region. It was probably this event (which is ascribed by some scholars to 307-306 BC) which affected the Teutones (Teutons - the origin of 'Teutonic') in the centre of the peninsula along with their northern neighbours, the Cimbri, enough to force them to migrate outwards in large numbers. A good deal of controversy exists as to whether particular tribes were German or Gaulish (Celtic). Both the Cimbri and Teutones appear to have borne some elements of Celtic society, although they were primarily Germanic. This trait seems to have been common with all Germanic peoples in the Cimbric peninsula, with them straddling both definitions (modern Danes share this identity, with a southern Scandinavian-originating Danish elite added on top of an earlier population to create it). By the time in which Germanic tribes were becoming key players in Western European politics in the last two centuries BC, the previously dominant Celts were on the verge of being conquered by Rome (see map link for general tribal locations). They had already been pushed out of northern and Central Europe by a mass of Germanic tribes which were steadily carving out a new homeland. A large-scale incursion of the sea into Jutland around the period between 120-114 BC is known as the Cimbrian Flood. It permanently altered the shape of the coastline and drastically affected the way people lived in the region. It was probably this event (which is ascribed by some scholars to 307-306 BC) which affected the Teutones (Teutons - the origin of 'Teutonic') in the centre of the peninsula along with their northern neighbours, the Cimbri, enough to force them to migrate outwards in large numbers. A good deal of controversy exists as to whether particular tribes were German or Gaulish (Celtic). Both the Cimbri and Teutones appear to have borne some elements of Celtic society, although they were primarily Germanic. This trait seems to have been common with all Germanic peoples in the Cimbric peninsula, with them straddling both definitions (modern Danes share this identity, with a southern Scandinavian-originating Danish elite added on top of an earlier population to create it).  Early Germanics were influenced by 'Northern Celts' for perhaps a millennium before the birth of Christ, although this assertion is somewhat contentious. Such a mixing could also well account for those Northern Celts being identified with the Belgae. The subject is discussed in greater detail in the accompanying feature (see link, right). The Teutones name breaks down into 'teut', meaning 'family, tribe', plus '-on', the definite article, and '-es', the plural suffix. 'Teut' appears to refer to family or tribe in the Celtic usage, not the Indo-Aryan which commonly informs Germanic language analysis. In Old Indian/Vedic it means 'strong'. In Latin (Q-Italic) it means 'all', or 'everyone' when applied to people. In OldPrussian (Baltic dialect), 'tulan' means 'much, a lot of', so there are a good many variations. Even so, the meaning of 'the people' is found in Celtic and P-Italic tongues, and also Germanic. For example, the Gothic 'thiuda' means 'the people'. Early Germanics were influenced by 'Northern Celts' for perhaps a millennium before the birth of Christ, although this assertion is somewhat contentious. Such a mixing could also well account for those Northern Celts being identified with the Belgae. The subject is discussed in greater detail in the accompanying feature (see link, right). The Teutones name breaks down into 'teut', meaning 'family, tribe', plus '-on', the definite article, and '-es', the plural suffix. 'Teut' appears to refer to family or tribe in the Celtic usage, not the Indo-Aryan which commonly informs Germanic language analysis. In Old Indian/Vedic it means 'strong'. In Latin (Q-Italic) it means 'all', or 'everyone' when applied to people. In OldPrussian (Baltic dialect), 'tulan' means 'much, a lot of', so there are a good many variations. Even so, the meaning of 'the people' is found in Celtic and P-Italic tongues, and also Germanic. For example, the Gothic 'thiuda' means 'the people'.  The answer to this mystery may be even more strange than a 'simple' Celto-Germanic crossover. One particular theory also explains many influences in the Celtic La Tène culture which the Cimbri seem to share. This is the so-called 'Thraco-Cimmerian Hypothesis', a rather controversial subject to say the least (see feature link for full details). This concerns an Eastern Celtic 38 group (in DNA analysis terminology), part of the Cimmerian-Scythian people. The Cimmerians blasted their way into the historical record in the eighth and seventh centuries BC, eventually settling to a large extent amongst the Thracian tribes. Some modern writers believe that a Thraco-Cimmerian migration westwards out of Thrace (following the Cimmerian settlement there) triggered cultural changes which contributed to the transformation of the Celtic Hallstatt C culture into the La Tène. Amongst the Celts, their original name for themselves - 'Galat' - appears to have survived best along the fringes of their expansion. Such groups would become isolated sufficiently that they had no competitors who were using the same name, and therefore had no reason to change that name (see, for instance, Galatians, Caledonians, and Galicia). If the Cimmerian name followed this usage pattern then the Cimbri of Jutland may indeed have been be a Cimmerian-Germanic/Celtic mix, retaining their old name (which could still have have an original meaning of 'compatriots' or 'companions'), but being designated by many modern scholars as a Germanic tribe with Celtic influences. The Cimbric/Teutones migration event of the late second century BC may have begun - or was part of - a population shift in southern Sweden. The same shift seemingly triggered the movement of the Goths into Central Europe, where they settled between the Oder and the Vistula in what is now Poland. It was also almost certainly the Cimbri and Teutones migration which triggered a large-scale influx of Belgic tribes into Britain, although this migratory route may already have started up as far back as the fifth century BC. The answer to this mystery may be even more strange than a 'simple' Celto-Germanic crossover. One particular theory also explains many influences in the Celtic La Tène culture which the Cimbri seem to share. This is the so-called 'Thraco-Cimmerian Hypothesis', a rather controversial subject to say the least (see feature link for full details). This concerns an Eastern Celtic 38 group (in DNA analysis terminology), part of the Cimmerian-Scythian people. The Cimmerians blasted their way into the historical record in the eighth and seventh centuries BC, eventually settling to a large extent amongst the Thracian tribes. Some modern writers believe that a Thraco-Cimmerian migration westwards out of Thrace (following the Cimmerian settlement there) triggered cultural changes which contributed to the transformation of the Celtic Hallstatt C culture into the La Tène. Amongst the Celts, their original name for themselves - 'Galat' - appears to have survived best along the fringes of their expansion. Such groups would become isolated sufficiently that they had no competitors who were using the same name, and therefore had no reason to change that name (see, for instance, Galatians, Caledonians, and Galicia). If the Cimmerian name followed this usage pattern then the Cimbri of Jutland may indeed have been be a Cimmerian-Germanic/Celtic mix, retaining their old name (which could still have have an original meaning of 'compatriots' or 'companions'), but being designated by many modern scholars as a Germanic tribe with Celtic influences. The Cimbric/Teutones migration event of the late second century BC may have begun - or was part of - a population shift in southern Sweden. The same shift seemingly triggered the movement of the Goths into Central Europe, where they settled between the Oder and the Vistula in what is now Poland. It was also almost certainly the Cimbri and Teutones migration which triggered a large-scale influx of Belgic tribes into Britain, although this migratory route may already have started up as far back as the fifth century BC. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| (Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from? Anne Katrine Gade Kristensen (Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, Hist-fil. Medd 57), from Celts and the Classical World, David Rankin (1996), from On the Ethnography of the Cimbri, C Rawlinson (Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, No 6, 1877), from Roman Soldier versus Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD, Lindsay Powell, from The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W Anthony, from Geography, Ptolemy, and from External Links: The Natural History, Pliny the Elder (John Bostock, Ed), and Geography, Strabo (H C Hamilton & W Falconer, London, 1903, Perseus Online Edition).) | ||

Along with all the other leaders of the Cimbri and Teutones, Teutobod, leader of the latter, is partially Celtic. The second part of his name, '-bod', is a Celtic word and the first part, whilst accepted by mainstream opinion as being a Germanic word, can be argued as being Celtic with a Germanic equivalent of 'folc' or 'folk'.  An illustration depicting the Teutones wandering in Gaul, part of a large-scale migration from modern Denmark into northern Italy in the second century BC An illustration depicting the Teutones wandering in Gaul, part of a large-scale migration from modern Denmark into northern Italy in the second century BC |

||

| ? - 102 BC | Teutobod / Theudobod | King of the Teutons. The legendary King Teutenbuecher. |

| 113 - 109 BC | Teutobod of the Teutones and Boiorix of the Cimbri lead a large-scale migration of their people from their homeland in what later becomes central and northern Denmark. Along the way they pick up Celto-Germanic Helvetii peoples (in territory which later becomes Franconia), but also drop off fragments such as the Atuatuci. Their passage sparks a partial tribal movement by elements of the Boii who invade the Norican region south of the Danube, and it is either the Cimbri or the Boii who attack the Scordisci Celts in the Balkans. Could this migration involve a far larger number of Germanic tribes than has previously been suspected? Certainly the general Germanic migration towards the lands of the Celts picks up pace in the first century BC, but tribal names such as the Tubantes, the 'mound people', suggest similar origins to those of the Cimbri and Teutones.  Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them |

|

| 109 - 105 BC | The wandering tribes enter greater Gaul in 109 BC, causing chaos amongst the Celtic tribes there and rendering critical the situation in the region. It is almost certainly this invasion which sparks a migration of Belgic peoples from the [Netherlands](FranceHolland.htm#Friso Kings) and northern Gaul into south-eastern Britain, although such a migration may already have started on a smaller scale. In 107 BC, a Roman defence against the Cimbri's allies, the Helvetii, at the Battle of Burdigala ends in defeat, further exacerbating the confused situation. | |

| 105 - 101 BC | The Cimbri and Teutones have ventured so far south into Gaul by this time that they break into Italy, coming up against the Roman republic. The resultant Cimbric War sees initial Teutones and Cimbri success against tribes which are allied to Rome, and a huge Roman army is destroyed at the Battle of Arausio in 105 BC.  Consul Gaius Marius rebuilds the Roman forces, also employing numbers of Iberian Mercenaries (see feature link), while the Cimbri raid into Iberia, specifically in Cantabri territory where they likely gain little. Consul Gaius Marius rebuilds the Roman forces, also employing numbers of Iberian Mercenaries (see feature link), while the Cimbri raid into Iberia, specifically in Cantabri territory where they likely gain little.  This vast map covers just about all possible tribes which were documented in the first centuries BC and AD, mostly by the Romans and Greeks, and with an especial focus on 52 BC (click or tap on map to view at an intermediate size) This vast map covers just about all possible tribes which were documented in the first centuries BC and AD, mostly by the Romans and Greeks, and with an especial focus on 52 BC (click or tap on map to view at an intermediate size) |

|

| In 102 BC the weakened Teutones are defeated and enslaved at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (near present-day Aix-en-Provence). The Cimbri are similarly destroyed at the Battle of Vercellae in 101 BC (potentially the home of the Libici Gauls). Remnants of the two tribes (probably a substantial number) remain in their homeland in the Cimbric peninsula. The Cimbri are able to send ambassadors to Rome in AD 5 (as reported by Pliny), but both groups are later absorbed by the incoming Angles and Jutes which ensures the disappearance of any remaining Celtic cultural and linguistic traces. This means that, when the Angles eventually migrate to Britain, the descendants of the Teutones go with them, undertaking another great migration. | ||

|