|

|

|

| (Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from the Columbia Encyclopaedia, Sixth Edition (2010), from the Britannica Concise Encyclopaedia (2010), from Historical Atlas of the Ancient World, 4,000,000 to 500 BC, John Haywood (Barnes & Noble, 2000), from The Ancient Near East, c.3000-330 BC, Amélie Kuhrt (Routledge, 2000, Volumes I & II), from The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History, Colon McEvedy (Penguin Books, 1967, revised 2002), from Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, Michael Road (Facts on File, 2000), from Mesopotamia: Assyrians, Sumerians, Babylonians (Dictionaries of Civilizations 1), Enrico Ascalone (University of California Press, 2007), from The Cambridge Ancient History, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards (Cambridge University Press, 1973), from A History of the Ancient Near East c.3000-323 BC, Marc van der Mieroop (Blackwell Publishing, 2004, 2007), and from External Links: Umm el-Marra, Syria (Joint Expedition), and Early Non-Cuneiform Writing?, Glenn Schwartz (Academia.edu, PDF available).) |

|

|

| c.2700 BC |

The first tombs at Tuba are constructed in what later becomes archaeological layers, known as Periods VI-IV. The city develops to become the capital of a small kingdom during the early centuries of the third millennium, although no records have survived to document it at a time before which writing has entered ancient Syria.  An aerial photo showing the present-day mound of Tell Umm el-Marra, believed to be the site of the ancient city of Tuba An aerial photo showing the present-day mound of Tell Umm el-Marra, believed to be the site of the ancient city of Tuba |

|

| An earthen rampart can be detected in the city wall trench in West Area A, suggesting that Umm el-Marra is already a large, fortified centre in the Early Bronze Age. |

|

|

| fl c.2700 BC |

? |

Unknown king or kings of early Tuba. |

| c.2500 - 2200 BC |

Tuba is at the height of its power and prosperity, and is mentioned inEbla's royal archives. A complex of at least seven tombs is constructed and maintained within the city. Sacrificial animals, including puppies and decapitated donkeys, are placed in the tombs alongside their human occupants. A previously unseen form of writing on four small clay cylinders is also included. This early writing is not cuneiform. In fact it seems less sophisticated than Sumer's cuneiform, and a translation currently remains unlikely due to the relatively small sample base. Additionally, if the nobility of Tuba have a palace or temple, no signs of it have been found to date.  The mud brick tombs contained decapitated animals, with the skulls on an adjacent ledge, alongside their human companions at Tell Umm el-Marra in Syria The mud brick tombs contained decapitated animals, with the skulls on an adjacent ledge, alongside their human companions at Tell Umm el-Marra in Syria |

|

| c.2100 BC |

Tuba is one of many cities which are affected at a time in which the number and size of settlements in northern Syria is reduced. Parts of the city are abandoned, along with many nearby settlements. Possibly, the region undergoes an economic downturn, with only cities which control the trade routes to the south managing to survive at all. This picture of decline in this period is one which is repeated across the region. Hatti in Anatolia shows a layer of destruction while in southern Mesopotamia theSumerians apparently undergo a climate-induced collapse which also affects [ Egypt](../KingListsAfrica/EgyptAncient.htm#1st Intermediate Period). Cities such as [Uruk](MesopotamiaUruk.htm#Fourth Dynasty) are struck and defeated by the Gutians at the same time as they destroy the Akkadian empire and carry off the Sumerian kingship, while others such as Eridu simply decline into inexistence. |

|

| c.1900 - 1800 BC |

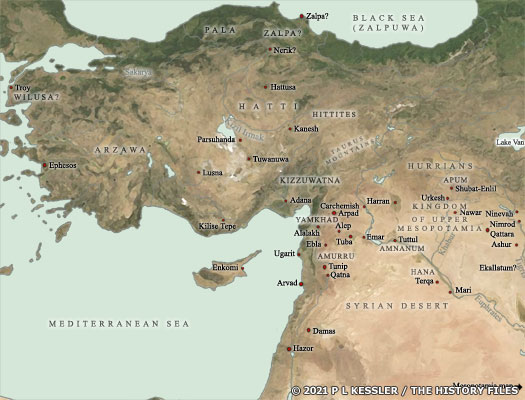

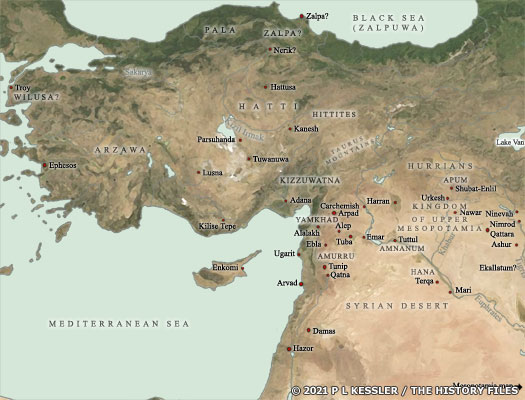

By this time a recovery is underway, but the Amorite tribes which have migrated into the region now control Tuba. The city becomes a major centre again, and serves as a subsidiary capital within the state of Yamkhad. A mud brick wall almost two metres thick is built around the 1.4 hectare central area of the city, with a city gate on the north-east side.  This map of the region shows the political situation around 2000 BC when the ancient Near East was undergoing a period of collapse (click or tap on map to view full sized) This map of the region shows the political situation around 2000 BC when the ancient Near East was undergoing a period of collapse (click or tap on map to view full sized) |

|

| c.1776 - 1600 BC |

Following the break-up of the short-lived but powerful kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia, the state of Yamkhad reasserts itself to become the dominant force in north-western Syria, controlling Tuba among many other cities. |

|

| c.1340 BC |

Tuba falls victim to an episode of substantial destruction. Some buildings are burned, with some of their household implements, luxury items, and other contents still inside. Suppiluliuma, the new Hittite ruler, takes control of northern [Syria](SyriaCityStates.htm#Greater Syrian States), causing destruction to some areas as he does so, and it seems likely that Tuba is one of his victims. |

|

| c.1200 BC |

The international system has recently been creaking under the strain of increasing waves of peasants and the poor leaving the cities and abandoning crops. Around the end of this century the entire region is also hit by drought and the loss of surviving crops. Food supplies dwindle and the number of raids by habiru and other groups of peoples who have banded together greatly increases until, by about 1200 BC, this flood has turned into a tidal wave.  Attacks by the Sea Peoples gathered momentum during the last decade of the thirteenth century BC, quickly reaching a peak which lasted about forty years Attacks by the Sea Peoples gathered momentum during the last decade of the thirteenth century BC, quickly reaching a peak which lasted about forty years |

|

| The Hittite empire is now looted and destroyed by various surrounding peoples, including the Kaskans and the Sea Peoples (and perhaps even selectively by its own populace). Some important Hittite cities and states, such as Tarhuntassa and Ugarit, disappear. Tuba is also abandoned as a city, although the mound on the site which has formed from two thousand years of occupation is reoccupied from time to time. Nothing great emergences from these temporary occupations, however, and today only archaeology remains to show it had ever been inhabited at all. |

|

|

|

|

|

Ancient Syria was much larger than its modern counterpart, being bordered by the Taurus Mountains in the north, the Upper Euphrates to the north-east, and the Syrian Desert to the south-east (see feature link). The name is Greek, which they used to describe various Assyrian peoples. The relatively few early Syrian states which appeared in the third millennium BC differed somewhat from their contemporaries in Sumer and Akkad. Instead of relying on river irrigation, the agriculture of the north was rain-fed, so yields were lower and larger areas had to be cultivated (although with less labour). As a result, northern cities tended to be smaller with more people living in outlying settlements. Although they were still city states at heart, they had more of an appearance of being small kingdoms due to the extended nature of their territory. The location of ancient Tuba (or Dub) is not known for certain, but scholars generally agree that the prime candidate is the site of Tell Umm el-Marra, about fifty kilometres to the east of the city of Alep in modern north-westernSyria. First occupied shortly after 3000 BC (by approximately 2700 BC), this site hosted a medium-size city, smaller than nearby Ebla to the west, but bigger than the average regional settlements. Its total built coverage amounted to about twenty-five hectares.

Ancient Syria was much larger than its modern counterpart, being bordered by the Taurus Mountains in the north, the Upper Euphrates to the north-east, and the Syrian Desert to the south-east (see feature link). The name is Greek, which they used to describe various Assyrian peoples. The relatively few early Syrian states which appeared in the third millennium BC differed somewhat from their contemporaries in Sumer and Akkad. Instead of relying on river irrigation, the agriculture of the north was rain-fed, so yields were lower and larger areas had to be cultivated (although with less labour). As a result, northern cities tended to be smaller with more people living in outlying settlements. Although they were still city states at heart, they had more of an appearance of being small kingdoms due to the extended nature of their territory. The location of ancient Tuba (or Dub) is not known for certain, but scholars generally agree that the prime candidate is the site of Tell Umm el-Marra, about fifty kilometres to the east of the city of Alep in modern north-westernSyria. First occupied shortly after 3000 BC (by approximately 2700 BC), this site hosted a medium-size city, smaller than nearby Ebla to the west, but bigger than the average regional settlements. Its total built coverage amounted to about twenty-five hectares.  Archaeological evidence indicates that it was the largest metropolis on the Jabbul Plain, an intersection of ancient trade routes which connected the eastern Mediterranean to locations as far afield as the Indus Valley culture. The earliest of its tombs are dated to the very beginning of its occupation, at a time in which there may have been animal and even some human sacrifice in the city, although the latter is still a controversial assertion (see feature link).

Archaeological evidence indicates that it was the largest metropolis on the Jabbul Plain, an intersection of ancient trade routes which connected the eastern Mediterranean to locations as far afield as the Indus Valley culture. The earliest of its tombs are dated to the very beginning of its occupation, at a time in which there may have been animal and even some human sacrifice in the city, although the latter is still a controversial assertion (see feature link).

An aerial photo showing the present-day mound of Tell Umm el-Marra, believed to be the site of the ancient city of Tuba

An aerial photo showing the present-day mound of Tell Umm el-Marra, believed to be the site of the ancient city of Tuba The mud brick tombs contained decapitated animals, with the skulls on an adjacent ledge, alongside their human companions at Tell Umm el-Marra in Syria

The mud brick tombs contained decapitated animals, with the skulls on an adjacent ledge, alongside their human companions at Tell Umm el-Marra in Syria This map of the region shows the political situation around 2000 BC when the ancient Near East was undergoing a period of collapse (click or tap on map to view full sized)

This map of the region shows the political situation around 2000 BC when the ancient Near East was undergoing a period of collapse (click or tap on map to view full sized) Attacks by the Sea Peoples gathered momentum during the last decade of the thirteenth century BC, quickly reaching a peak which lasted about forty years

Attacks by the Sea Peoples gathered momentum during the last decade of the thirteenth century BC, quickly reaching a peak which lasted about forty years