The Amphibians Came to Conquer [Chapter 14] (original) (raw)

Chapter XIV

Planning and Paring the Japanese Toenails in New Georgia

New Georgia--TOENAILS

TOENAILS was the code name given to the New Georgia Operation. The New Georgia landings in the Central Solomons commenced on 30 June 1943. Rear Admiral Turner was relieved of command of the Amphibious Forces, Third Fleet (South Pacific) by Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson (1909), on 15 July 1943. The New Georgia operation was completed on 25 August 1943. This chapter will deal with the planning phase and the chapter following will deal with the amphibious operations occurring prior to 15 July 1943.

Long Range Planning--Breaking the Bismarck Barrier

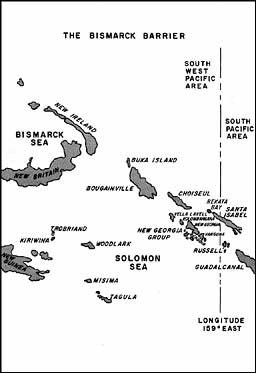

The thinking of most planners in late 1942 was that in order to break the Bismarck Barrier, Rabaul had to be seized. To seize Rabaul, the United States had to have airfields within fighter plane range of Rabaul. To get such airfields, the United States must seize central, then northern islands in the Solomon chain as well as a position at the western end of New Britain Island, at whose eastern extremity Rabaul was located.

On 8 December 1942 the Chief of Staff COMSOPAC (Captain M. R. Browning) sent a memorandum to Rear Admiral Turner and to the Commanding General Amphibious Corps directing:

Planning sections initiate a preliminary examination of the possibility of our Seizing this area [Roviana Lagoon, New Georgia] in the near future.

On 16 January 1943, a large conference was held by COMSOPAC for:

--481--

--482--

An informal discussion as to availability of units and supplies for offensive operations--objective Munda.1

In this latter memorandum it was assumed for "discussion purposes" that the movement would be a "shore to shore movement" from Guadalcanal to New Georgia of one Regimental Combat Team and two Raider Battalions.

At the same time that Rear Admiral Turner and COMSOPAC planners were focusing on Munda and New Georgia, CINCPAC planners were focusing on Rekata Bay and Santa Isabel Island. They opined:

The choice between Munda and Rekata, for our next objective in the Solomons, is a close one, but hydrography makes the latter preferable--even though we have to build a field there ourselves.2

With the choice such a close one, and with SOPAC opting strongly for Munda, CINCPAC in due time gave his approval for this objective.3

Objective the New Georgia Group

The New Georgia Group in the Middle Solomons covers an area 125 miles in length and 40 miles in width. It contains 12 large islands. COMSOPAC had a particular and immediate interest in four of the largest of these, New Georgia, Rendova, Kolombangara and Vangunu. Munda airfield located on New Georgia, the largest island in the group, was approximately 180 miles northwest from Guadalcanal and about 30 hours running time for an LCT. Thoughts of possession of Munda's 4,700-foot runway brought pleasant smiles to the planners' faces, for while the New Georgia Group was only a first step, one-third of the way to Rabaul, it was a step everyone at the time said was necessary.

All the charts of the pre-World War II period have all the larger islands in the New Georgia Group labeled "densely wooded." Those few who had visited them in pre-World War II days declared them heavily jungled. New Georgia Island was about 45 miles long and 30 miles wide, and the only really large low flat area on the island was around Munda airfield at the southern end of its northwest corner.

--483--

Kolombangara across Kula Gulf to the northwest of New Georgia Island reached an elevation of 5,450 feet, while New Georgia Island itself topped out much lower at 2,690 feet. However, all the islands in the New Georgia Group were rugged with numerous peaks. There were no roads and few trails through the jungle growth. The islands were surrounded by an almost continuous outer circle of coral reefs and coral filled lagoons. The trees and undergrowth came right down to the beaches over a large part of the islands making it difficult to choose an area where it would be possible to move any logistic support inland.

It is desirable to recall that while the Joint Chiefs had prescribed that CINCPAC and COMSOPAC were to be the immediate commanders for Phase One (PESTILENCE) of the initial offensive move into the Solomons Islands, Phase Two which was the capture of the rest of Japanese-held Solomons and positions in New Guinea and Phase Three, the capture of Rabaul, were to be accomplished under the command of CINCSWPA, General Douglas MacArthur.4

On 6 January 1943, Admiral King had made a very definite attempt to have the naval tasks of these prospective Phase Two and Phase Three operations continue under the command of CINCPAC and his area subordinate, COMSOPAC, by limiting General MacArthur to the strategic direction of the campaigns. This did not evoke a favorable response from his opposite number in the Army, but it did stir the Joint Chiefs, on the 8th of January 1943, to ask General MacArthur how and when he was going to accomplish the unfinished task of Phase Two of PESTILENCE5

At the Casablanca Conference, held from 14-23 January 1943, the Task Three decision in the 2 July 1942 Joint Chiefs PESTILENCEdirective, which ordered the seizure of Rabaul in New Britain Island at the head of the Solomons, was reaffirmed. When this good news reached the South Pacific, where the concern was that the area might draw a later and lower priority than the Central Pacific, Vice Admiral Halsey on 11 February sent his Deputy Commander, Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson, to consult and advise with General MacArthur. Rear Admiral Wilkinson also carried COMSOPAC's comments on CINCSWPA's plans for Phase Two which were contained in CINCSWPA's despatches to the Joint Chiefs, information copies of which had been sent to CINCPAC and COMSOPAC.

--484--

Just a few days before Rear Admiral Wilkinson flew off to Australia, Admiral King on 8 February 1943 sent another memorandum to General Marshall, commenting on General MacArthur's reply to the Joint Chiefs of Staff despatch of 8 January 1943 and indirectly commenting on the command problem in his area.6

On the day before Lincoln's Birthday 1943, Vice Admiral Halsey informed COMINCH that the rapid consolidation of Japanese positions in the New Georgia Group emphasized the need for early United States seizure of these islands. He recommended that pressure on the Japanese be continued in the Southern Solomons, and that the occupation of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands (specifically Makin and Tarawa) in the Central Pacific, suggested by COMINCH as the next appropriate task after CLEANSLATE, be deferred until later.7

CINCPAC went along with this COMSOPAC recommendation.

On 14 February 1943, when there were many who believed the Japanese, now ousted from the Southern Solomons, would strike at some other island group in the South Pacific, Admiral Nimitz made the very shrewd estimate that the withdrawal of the Japanese from Guadalcanal probably indicated that the Japanese would shift to the strategical defensive in the South Pacific. Post-war Japanese records indicate that this is what happened.8

On 17 February 1943, the CINCPAC Staff Planners "assumed" that COMSOPAC "will attack Munda next and will employ one Marine Division." This represented some beefing up from the earlier concept of one Regimental Combat Team and two Raider Battalions, but still was a fair step away from the realities of the operation insofar as the landing forces are concerned. The planners reported to CINCPAC:

It seem entirely feasible to make a simultaneous thrust up the Solomons, and in the Gilberts. Capture of objectives seem probable. Holding in Gilberts seems doubtful. . . . Because of preparation time required, May 15, 1943, is selected as the target date.9

The guesstimate of a Dog Day of 15th of May by the CINCPAC Staff was missed by more than a long month, for it was the 21st of June before two companies of Marines were landed ahead of schedule at Segi Point, New

--485--

--486--

Georgia, and the 30th of June before Rendova and other islands in the New Georgia Group were invaded on schedule.

But in the four months from late February to late June 1943, much new meat was put in the grinder for future operations by the Joint Chiefs, only a small portion directly concerned with the South and Southwest Pacific. So it was not until the end of March 1943 that the Amphibious Force of the South Pacific, and other interested commands learned just what they were to do, although even then no definite time schedule was provided.

Talking it Over at a High Level

On 12 March 1943, the Pacific Military Conference opened in Washington, D. C., with considerable talent present from the major commands of the Pacific. The chore was to examine, discuss, and if possible, decide upon ELKTON, which was General MacArthur's plan for carrying out Phase Two and Phase Three of the Joint Chiefs' 2 July 1942 directive for PESTILENCE.

The Navy planners sat back and drooled as General MacArthur's Chief of Staff set forth the considerable forces, particularly Army Air Forces, needed to carry out the ELKTON Plan. All during Phase One of the PESTILENCEOperation,10the SOPAC Navy felt that the Army Air Forces had short changed their needs in the South Pacific in favor of the bomber offensive against Germany. It was a distinct pleasure to hear the Army planners, in effect, saying that in order to move forward toward Rabaul, it would take about twice the then current allocation of air strength in the SOPAC-SOUWESPAC Areas.

Out of nearly ten days of proposal and counter-proposal and a meeting of some of the Pacific planners with the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 21 March 1943 came, in effect, a reaffirmation of Phase Two of the Joint Chiefs' PESTILENCE directive of 2 July 1942 and a requirement that it should be accomplished during 1943.

However, the Joint Chiefs made it clear that a new start was being made by cancelling the old 2 July 1942 directive. They issued a new directive for an operation labeled CARTWHEEL, an operation for (1) the seizure of the Solomon Islands up to the southern portion of Bougainville and (2) driving the Japanese out of certain specific areas in New Guinea and in Western New Britain. The Joint Chiefs made it equally clear that only a

--487--

small proportion of the additional forces requested by General MacArthur would be supplied from the United States.

The Problem of Command Settled

The Joint Chiefs directed that the operations in the middle Solomons be conducted under the direct command of COMSOPAC, operating under the general (strategic) directives of CINCSWPA. Ships and aircraft from the Pacific Fleet, unless assigned by the Joint Chiefs to CARTWHEEL tasks, would remain under the control and allocation of the CINCPOA.11

It was a happy fact, from the Navy's viewpoint, that command during the CARTWHEEL Operation was to be exercised very much along the lines recommended by COMINCH to the Army Chief of Staff on 6 January 1943.

On the Other Hand--The Japanese

The Japanese had largely by-passed the New Georgia Group in their giant strides towards New Caledonia until the struggle for Guadalcanal was in its later stages. Then they landed at Munda Point, New Georgia, on 14 November 1942 and, starting a week later, built a 4,700-foot airstrip during the next month. Following this, a Japanese airfield was built at Vila on Kolombangara Island just a scant 25 miles to the northwest of Munda. Two Special Naval Landing Forces (SNLF) were provided and the Japanese turned to and rapidly built up defenses around these two very usable and supporting airfields.

Further north up the Solomons, the Japanese also expanded their air facilities. There was an airfield at the south end of Vella Lavella Island, fifty miles to the northwest of Munda, and there were five airfields on Bougainville Island commencing with one 125 miles northwest of Munda. In addition, there was Ballale Island airfield in the Shortland Islands just south of Bougainville Island, and another airfield on Buka Island just north of Bougainville Island. All were backed up by the five airfields around Rabaul, 375 miles northwest of Munda. The Japanese worked diligently

--488--

for six months to perfect their defenses in the New Georgia Group. During a major part of these six months, the SOPAC forces planning to land in the New Georgia Group waited for the questions of high command and of concurrent operations in the Southwest Pacific Area to be settled before really being able to plan definite steps to push the Japanese out at a reasonably sure date.

Not that the problem of bringing available United States air power to bear in the Central Solomons was overlooked during this delay. Soon after capturing Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, a second airstrip on Guadalcanal had been started. Now there were four airstrips on Guadalcanal and two more in the Russells were being made ready. Planes from these fields, by regular bombing raids, kept the Japanese alert and particularly busy filling up holes on the Munda and Vila airfields. To show the extent of the air effort, CINCPAC reported that during June 1943, 1,455 SOPAC planes dropped 1,156,075 pounds of bombs on Japanese objectives in the Solomons.12Surface task groups had bombarded Munda and Vila on 6 March and again on 13 May 1943.

--489--

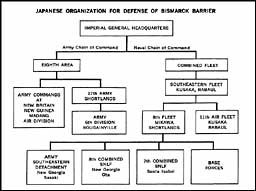

Japanese Area Command Structure

The Japanese Area Command structure was quite different from that of United States forces. However, just as the United States Joint Chiefs, in due time, recognized that for immediate command purposes the operations in the Buna-Gona area of New Guinea must be quite separate from those along the Solomons chain of islands, the Japanese high command recognized the same necessity. The Japanese met the problem in a different way than the United States. They assigned prime responsibility in the New Guinea-New Britain-New Ireland area of operations to their Eighth Area Army, and the prime responsibility for the Central Solomons Island Area to the Southeastern Fleet of their Navy, with command lines running in separate Service channels all the way back to Tokyo. No one Japanese military officer in the area of operations had overall strategic control.

The Japanese then threw in another hurdle to smooth command lines for their defense of the Solomons as a whole. The Commanding General _17th Army,_a major command of the Eighth Area, was given the responsibility for defense in the Northern Solomons and his command lines flowed upward through his Army superior in Rabaul. So the Japanese Navy was responsible for the Middle Solomons, and the Japanese Army for the Northern Solomons.

The Navy Commander of the Japanese Southeastern Fleet and of the 11th Air Fleet, wearing the two hats, was Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka. Vice Admiral Kusaka's immediate superior was Admiral Mineichi Koga, Commander in Chief Combined Fleet, with headquarters in Truk. Kusaka's immediate junior was Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa who commanded the _Eighth Fleet._Kusaka had orders to pursue an "active defense" in the Solomons. Mikawa's on the spot subordinate in the Central Solomons was Rear Admiral Minoru Ota, who with "primary responsibility" coordinated the efforts of the Joint Army-Navy Defense Force in the New Georgia Group. He did just that. He did not command. The Japanese Army Commander on New Georgia was Major General Noboru Sasaki, Commander New Georgia Detachment, Southeastern Army.

When Major General Noboru Sasaki in late June was directed to take over from Rear Admiral Ota the "primary responsibility" for the efforts of the_Joint Army-Navy Defense Force_ in the New Georgia Group, he and Ota were continued on a "cooperation" basis rather than Sasaki being placed in "command." The only change was in the man who held the hot potato of "primary responsibility" in a cooperative effort.

--490--

JAPANESE ORGANIZATION FOR DEFENSE OF BISMARCK BARRIER

It would appear that the United States forces had a real command advantage in seeking to break through to the Bismarck Barrier over the Japanese seeking to defend its approaches, since one military officer, General MacArthur, who was actually in the area of operations, had over-all strategic control, and could time the movements of his subordinates in the two- pronged offensive.

The Japanese commanders, being on the strategic defensive, naturally had to react individually depending on the time and place they were attacked. But there was no Japanese area commander whose primary duty included the concentration of reserve forces prior to attack, and shifting these forces as the enemy attack developed.

Japanese Defense Preparations

The New Georgia Group lay on the direct route from Guadalcanal to Rabaul, and had two good air bases, so the Japanese assigned to this group about 70 percent of their defensive troop strength available in the Central

--491--

Solomons. Their Navy sent the 7th Special Naval Landing Force (the Marines of the Japanese Navy) to Kolombangara and the _6th Special Naval Landing Force_to New Georgia. Together these units formed the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force of about 4,000 men. These naval fighting units were gradually reinforced with Army troops of the Southeastern Army until the total strength in the New Georgia Group reached 10,500, about half of whom were on New Georgia Island. The Japanese also had the 7th Combined Special Naval Landing Force of about 3,000 men on Santa Isabel Island and 2,000 more on Choiseul in the Central Solomons. There also were about 10,000 Japanese Army troops in the Northern Solomons.

The Japanese had lookout stations scattered along the coasts of the islands of the New Georgia Group. Defensively, they had major subordinate commands and troops at Munda Point and Kolombangara, and minor troop units at Viru Harbor in southwest New Georgia, along eastern Vangunu Island opposite Wickham Anchorage and on Rendova Island. In trying to defend everywhere, there was some splintering of the forces available. The Japanese made it possible for Task Force 31 of the South Pacific Force to render ineffective a sizable proportion of the total Japanese defensive troop strength, by containing, scattering or capturing these various outpost contingents, which served no useful defensive purpose insofar as Munda and Vila airfields were concerned.

A professional post-war estimate based on available Japanese documents is that the Japanese had about 25,000 troops in all of the Solomons in June 1943 with larger contingents in both the Bismarck Archipelago (43,000) and in eastern New Guinea (55,000).13Presumably these allocations of troop strength roughly indicated how the Japanese evaluated the degree of danger to each area, and their own desires to retain them.

Just as the United States in the earlier days of the war did not know where the next enemy amphibious offensive might be headed or assault landed, the Japanese did not know where our offensive was headed nor where the assault stepping stones might be picked. With the Japanese in the middle Solomons, the immediate problem was whether United States eyes were lighting on the New Georgia Group of islands or on Santa Isabel, which the CINCPAC planners had favored. Santa Isabel contained the highly usable seaplane base at Rekata Bay, where unfortunately Rear Admiral

--492--

Turner had focused his eyes on the disaster-tinged evening of 8 August 1942. But Santa Isabel lay northeastward of the direct route to Rabaul from Guadalcanal and presumably so seemed to the Japanese a less likely objective for a United States attack than the New Georgia Group. In any case the Japanese had but 3,000 defenders on Santa Isabel compared to 10,500 in the New Georgia Group.

The Japanese in the Central Solomons pressed their defensive preparations with their typical military energy throughout the first six months of 1943, despite harassment from the air and sea. More particularly in the New Georgia Group, and in the Munda area, the Japanese believed that a major attack was most likely to come overland from Bairoko Harbor, seven miles to the north of Munda, and so a fair share of their defensive artillery was sited to meet an offensive from that direction.

They also knew that an attack on the Munda airstrip might come from the Roviana Lagoon which Vice Admiral Halsey's planners had named back in December 1942, or over the Munda Bar. But they knew that Roviana Lagoon was blocked from seaward by islands, coral reefs, and shallow surf-ridden entrances, suitable only for landing boats, or at best, an LCT. So they sited their seacoast guns to protect from an attack over Munda Bar, which to the United States Navy had looked like a near impossible obstacle.

That the degree of readiness of the Japanese in the Munda area to provide "an active defense" was high, is attested to by the length of the struggle before the Munda airstrip was captured on 5 August, and by the large reserve U.S. Army forces that had to be brought in to overwhelm the 5,000 defenders on New Georgia Island.

Organizational Changes

Admiral King felt that part of the Navy's command difficulties with the Army arose from the fact that many of the organizational groupings of ships of the United States Fleet, called task forces, were identified by the areas where there were naval tasks to be accomplished on a continuing basis. Examples are: Panama Patrol Force, Northwest Africa Force, Southwest Pacific Force. Therefore, an officer of the Army exercising "area command" might logically expect to exercise direct control on a continuing basis over the ships carrying his area name tag. This led to area efforts to limit these task forces to minor offensive and defensive chores to the neglect of the broader, more important, and specific Naval and Fleet mission to "maintain control of the sea."

--493--

To alleviate this problem, on 15 March 1943, all the ships of the United States Fleet were changed from an area command nomenclature and put into numbered Fleets, the Fleets operating in the Pacific being allocated odd numbers. PHIBFORSOPAC became PHIBFORTHIRDFLT, or THIRDPHIBFOR. Rear Admiral Turner lost his well-known designation as CTF 62 and became CTF 32.14Despite this ordered change, for some months Vice Admiral Halsey, Commander Third Fleet, continued to use his COMSOPAC title.

Delay and More Delay

On 3 March 1943 COMSOPAC informed COMINCH and CINCPAC that the tentative D-Day for the next offensive was April 10th.15The actual major movement of SOPAC forces into the Middle Solomons was 50 long days later. This delay beyond a date when the Area Commander reported his forces would be ready to move, marked the TOENAILS operations as different from all others in which the Turner staffs participated, since in previous and subsequent operations, the amphibious forces had great difficulty making the desired readiness date.16

On 28 March COMSOPAC dismounted from his galloping white charger long enough to tell the Joint Chiefs that he concurred with delaying major operations by SOPACFOR against New Georgia until the air base on Woodlark Island in SOWESPAC's domain was commissioned.17

It was quite obvious that since General MacArthur had been given the strategic direction of the operation, Vice Admiral Halsey could not move his invasion forces until General MacArthur approved. Admiral King was breathing hotly on the neck of COMSOPAC (later known as Commander Third Fleet) and Vice Admiral Halsey was breathing hotly on the neck of Rear Admiral Turner, but no final Dog Day could be set until after the staff representatives of Commander Third Fleet and CINCSWPA returned from Washington on 8 April 1943.18

On 15-16 April 1943, soon after the return of the Third Fleet representatives from Washington, Vice Admiral Halsey had a conference with General

--494--

Training Seabees at Noumea, New Caledonia, for impending operations, April 1943. Rear Admiral Turner, Commander Third Amphibious Force, with his staff.(NR & L (MOD) 31940)MacArthur. Vice Admiral Halsey happily agreed with General MacArthur's desire for setting Dog Day on 15 May in order that SOPAC Operations would start on the same day as the operations in the Southwest Pacific Area. These latter operations were for the seizure of Woodlark Island 210 miles west from the airfields in the south of Bougainville, as well as for the seizure of the Trobriand Islands further west. Soon General MacArthur delayed his readiness date to 1 June and eventually he said that his forces could not be ready before a 30th June date. When Commander Third Fleet was subjected to further Navy high command urging to get General MacArthur to set an earlier date, Vice Admiral Halsey responded by proposing that SOPACFOR charge up the Solomons and make a night landing on Rendova. However, he finally ended the high-level kibitzing by informing his superiors on 26 May that after much discussion and a reappraisal of the specific effort required by each subordinate command in the Third Fleet, a 30 June D-Day was agreeable to him also.19

--495--

Rear Admiral Turner with Seabee officers after witnessing training operations.(NR & L (MOD) 31396)Back on 9 March, the level of naval operations in the lower Solomons had so dropped off that COMSOPAC, upon Rear Admiral Turner's urging, directed the commencement of a three-week period of training of new units and of specific preparations for the next offensive.20With no specific Dog Day to plan for, this seemed a most desirable stop-gap measure.

The First Definite Plan

About a month after the Third Fleet planners returned from General MacArthur's Headquarters, COMSOPAC issued his first definite planning directive for the TOENAILS Operation. This was on 17 May 1943 and he directed that:

Forces of the South Pacific Area will seize and occupy simultaneously positions in the southern part of the NEW GEORGIA Group preparatory to a full scale offensive against MUNDA-VILA and later BUIN-FAISI [the southern end of Bougainville].21

--496--

The specific tasks were to seize, hold, and develop:

- a staging point for small craft in:

- the Wickham Anchorage Area in the southeastern part of Vangunu Island and 50 miles from Munda airstrip.

- Viru Harbor on New Georgia Island 30 miles southeast of Munda airstrip.

- a fighter airstrip at Segi, New Georgia, 40 miles from the Munda airstrip.

- Rendova Island, whose northern harbor was just 10 short miles south of Munda, as a supply base, advanced PT Base, and an adequate support base to accommodate amphibians prior to their embarkation for an assault on Munda and/or Vila.

Dog Day was set for June 15th "or shortly thereafter." This date was in accordance with the good old Navy practice of getting everyone pressing to be ready ahead of the real date when they had to be ready.

Between the day when this order was issued and June 3rd when COMSOPAC issued his Operation Plan 14-43, there were several changes made in the planning, but the most important, at Rear Admiral Turner's working

--497--

level, was the change of Dog Day to 30 June 1943, and the change in Task Force designation for the Assault Force from Task Force 32 to Task Force 31.

COMSOPAC's Warning Instructions contained no information or instructions in regard to the components or the command of the New Georgia Occupation Force. Neither did his Operation Plan 14-43 issued two weeks later.

Rear Admiral Turner's (CTF 31) Operation Plan A8-43 gave the components of the New Georgia Occupation Force and indicated Major General Hester was the Commander, but stated in a separate subparagraph that command would pass from CTF 31 to other military authorities when so directed by Commander Third Fleet. Presumably, but not explicitly stated, this would occur when Major General Hester was established ashore on New Georgia Island and was ready to assume the command responsibility. Under these circumstances he would notify Commander Third Fleet and Rear Admiral Turner, CTF 31, would make his recommendation to Commander Third Fleet in the matter and the latter would decide whether, or when, the command should pass.

The failure of Vice Admiral Halsey's Operation Plan to spell out the command matter, after his experience in regard to the same problem in the latter phases of WATCHTOWER, is not understood.22

Logistics Comes of Age in SOPAC

In February 1943, COMSOPAC launched logistics operation DRY-GOODS. This was the supply part of the logistic support needed to conduct the next big operation in the Middle Solomons. DRYGOODS called for building up on the Guadalcanal-Russell Islands some 50,000 tons of supplies, 80,000 barrels of gasoline (and storage tanks to hold this amount) and the tens of thousands of tons of equipment for the various units slated to participate in this next operation, which in due time was named TOENAILS. Rear Admiral Turner had drafted a memorandum to COMSOPAC on 14 January 1943, recommending this essential logistic step for future operational success. Despite all that could be said against the inadequacy' of the unloading and storage facilities to be available at Guadalcanal in the spring of 1943, Vice Admiral Halsey gave the proposal a green light and thus made a major contribution to the success of TOENAILS. Since everyone

--498--

in the United States with an alert ear knew by this time that Guadalcanal's code word was CACTUS, Guadalcanal received a change of code name from CACTUS to MAINYARD for the purpose of the DRYGOODS Operation.

On 20 May 1943, COMSOPAC created a Joint Logistic Board, composed of:

- Commander Service Squadron, SOPAC,

- Commanding General, Services of Supply, SOPAC, Army,

- Commanding General, Supply Service, First Marine Amphibious Corps, and

- Commander Aircraft, SOPAC (represented by COM Fleet Air, Noumea).

The Board was charged with keeping the appropriate departmental authorities in Washington informed of present and future Service requirements, with providing interchange of emergency logistical support within SOPAC, and with recommending to Washington appropriate levels of supply within SOPAC.

The Landing Craft

SOPAC planning for TOENAILS was predicated upon the arrival in the South Pacific of an adequate number of LSTs (Landing Ship Tank), LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) and LCTs (Landing Craft Tank). When delay succeeded delay in the delivery of these new landing craft, some being built by commercial shipyards themselves newly built, it became apparent that there would be little time to break them in to the hazards of the Solomons before they would have to load for TOENAILS. In this respect, it is obvious that Vice Admiral Halsey's desire for an April or May D-Day for TOE-NAILS was constantly tempered by the constant slippage of the arrival dates of the landing craft.

The first LSTs assigned to the South Pacific were built at three East Coast yards and were commissioned in December 1942 and January 1943. The LST used in the South Pacific had an overall length of nearly 328 feet, a 50-foot beam, and a draft of 14 feet when it displaced 3,776 tons fully loaded. Presumably when the LST blew its ballast tanks, its draft was 3 feet, 1 inch forward and 9 feet, 6 inches aft, but this desirable state for unloading Marine or Army tanks through the bow doors on the perfect

--499--

beach gradient was rarely realized. All the large landing craft were diesel-engined.

The Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) was 157 feet overall, had a beam of 23 feet, and a displacement of 380 tons. The LCI was the fastest of the large landing craft with a designed maximum speed of 15 knots which permitted these craft to cruise at about 12 knots in a generally smooth sea. The LCI could carry 205 troops and 32 tons of cargo in addition to the ship's company and normal stores. The draft when loaded for landing was never less than 3 feet, 8 inches forward and 5 feet, 6 inches aft, but constant purges of stores and gear had to be held to even approach this desirable draft. The LCI discharged troops and equipment by means of gangways hinged to a platform on the bow, and lucky were the troops who got ashore in water less than shoulder high. The LCI complement was two officers and 22 men, but when they had that number they were equally fortunate.

The first LST which made news in the Landing Craft Flotillas, South Pacific Force was the LST-446 which arrived in the South Pacific about 6 March 1943. The Commanding Officer LST-446 in a loud howl sent off to OPNAV, CINCPAC, BUSHIPS, and half-a-dozen afloat commands, enumerated the trials and tribulations of a new type of ship operating in the Southern Solomons, and objected strenuously to his ship "being loaded" while the ship was beached.

The Commanding Officer continued:

An LST is the only ship in the world of 4000 tons or over that is continuously rammed onto and off of coral, sand and mud.23

Despite this dim view of what became a very routine function, the arrival of LST-446 was a very real advance in the readiness of Rear Admiral Turner to conduct TOENAILS. Admiral Turner said:

The LST was and is still a marvel, and the officers and men who manned them hold a high place in my affections.24

Captain G.B. Carter, Commander Landing Ship Flotilla Five, arrived in Noumea on 14 May 1943 with the first large group of the Landing Ship Tanks destined to see action in SOPAC. The officers and men of the 12 newly commissioned LSTs he brought with him, all carrying an LCT on board for launching upon arrival at destination, had learned "to go to sea" during their 67-day, 9,500-mile passage at 7 to 9 knots from the East Coast of

--500--

the United States to Noumea. For many of them, this long cruise was also their first.

The LSTs in the South Pacific wore no halos. But, because these large and ungainly ships overcame dozens of engine and electrical casualties, and even ended up by towing their escorts and a coastal transport part way across the Pacific, they engendered a certain respect from the older units of the Fleet in that area.

Due to the almost complete absence of war diaries, the exact date of the arrival of the various units of LCI Flotilla Five in the South Pacific is unknown. LCI-328 arrived in Noumea from Panama on 2 April 1943. _LCI-63_arrived in Noumea also from Panama on 14 April and went alongside _LCI-64._On 14 April 1943 the TF 63 War Diary reported seven LCIs at Noumea. On 15 April it was noted that 23 LCIs of Flotilla Five (all except LCI-329) were present in SOPAC in an upkeep status.25

Both the LSTs and the LCIs, upon arrival in the South Pacific, were given a two-week period of upkeep and maintenance by Rear Admiral Turner to correct the many ailments arising during their arduous passage across the wide Pacific.

It can be observed that the written records located of LCTs and LCIs of this period are few. The memories of the few seasoned officers who are still above ground and who made the passage aboard these landing craft are faint. Despite these handicaps, it can be written with certainty that the LCIs had less than eight weeks and the LSTs fewer than four weeks for the multiple tasks of operational amphibious training, movement to the staging areas 800 miles away, and then specific preparation and rehearsal loadings for TOENAILS.

Organization--Third Fleet Amphibious Force

On D-Day for TOENAILS Rear Admiral Turner, COMPHIBFOR, Third Fleet, still using his SOPAC title, issued an administrative organization chart, which showed that a considerable number of the more senior WATCHTOWER Commanding Officers were available to carry their acquired skills, burdens and satisfactions into the TOENAILS Operation. At long last their

--501--

Transport Commodore was a Commodore in fact.26The organization was as follows:

Amphibious Force, South Pacific

| Commander Amphibious Force South Pacific | | Rear Admiral R.K. Turner (1908) | | ---------------------------------------- | | ---------------------------------- | | Chief of Staff | | Captain Anton B. Anderson (1912) | | APA-4 McCawley (Flagship) | | Commander Robert H. Ridgers (1923) |

TRANSPORTS, SOUTH PACIFIC AMPHIBIOUS FORCE

Commander Transports, PHIBFORSOPAC--Commodore Lawrence F. Reifsnider (1910)

APA-14 Hunter Liggett (Flagship) Captain R.S. Patch, U.S. Coast Guard_Transport Division Two_--Captain Paul S. Theiss (1912)

APA-18 President Jackson (F) Captain Charles W. Weitzel (1917)

APA-20 President Hayes Captain Francis W. Benson (1917)

APA-19 President Adams Captain Frank Dean (1917)

AKA-8 Algorab Captain Joseph R. Lannom (1919)_Transport Division Eight_--Captain George B. Ashe (1911)

APA-17 American Legion (F) Commander Ratcliffe C. Welles (1921)

APA-27 George Clymer Captain Arthur T. Moen (1918)

APA-21 Crescent City Captain John R. Sullivan (1918)

AKA-12 Libra Captain William B. Fletcher (1921)

AKA-6 Alchiba Commander Howard R. Shaw (1921)_Transport Division Ten_--Commodore Lawrence F. Reifsnider (1910)

--502--

APA-14 Hunter Liggett (F) Captain R.S. Patch, USCG

APA-23 John Penn Captain Harry W. Need (1918)

AKA-9 Alhena Commander Howard W. Bradbury (1921)

AKA-5 Fomalhaut Captain Henry C. Flanagan (1921)_Transport Division Twelve_--Commander John D. Sweeney (1926)

APD-6 Stringham (F) Lieutenant Commander Joseph A. McGoldrick (1932)

APD-1 Manley Lieutenant Robert T. Newell, Jr. USNR

APD-5 McKean Lieutenant Commander Ralph L. Ramey (1935)

APD-7 Talbot Lieutenant Commander Charles C. Morgan, USNR

APD-8 Waters Lieutenant Charles J. McWhinnie, USNR

APD-9 Dent Lieutenant Commander Ralph A. Wilhelm, USNR_Transport Division Fourteen_--Captain Henry E. Thornhill (1918)

APA-7 Fuller Captain Melville E. Eaton (1921)

APA-4 McCawley (FF) Commander Robert H. Rodgers (1923)

AKA-13 Titania Commander Herbert E. Berger (1922)_Transport Division Sixteen_--Lieutenant Commander James S. Willis (1927)

APD-10 Brooks Lieutenant Commander John W. Ramey (1932)

APD-11 Gilmer Lieutenant Commander John S. Horner, USNR

APD-12 Humphreys Lieutenant Commander John S. Horner, USNR

APD-13 Sands Lieutenant Commander John J. Branson (1927)

--503--

APD-18 Kane Lieutenant Commander Robert E. Gadrow (1931)

_Transport Division Twenty-Two_--Lieutenant Commander Robert H. Wilkinson (1929)

APD-15 Kilty (F) Lieutenant Commander Dominic L. Mattie (1929)

APD-17 Crosby Lieutenant Commander Alan G. Grant, USNR

APD-16 Ward Lieutenant Frederick W. Lemley, USNR

APD-14 Schley Lieutenant Commander Horace Myers (1931)MINESWEEPER GROUP, SOUTH PACIFIC FORCE

(TEMPORARY ASSIGNMENT)

Commander Stanley Leith, USN, Commanding (1923)DMS-13 Hopkins (F) Lieutenant Commander Francis M. Peters, Jr. (1931)

DMS-10 Southard Lieutenant Commander Frederick R. Matthews (1935)

DMS-11 Hovey Lieutenant Commander Edwin A. McDonald (1931)

DMS-14 Zane Lieutenant Commander Peyton L. Wirtz (1931)

DMS-16 Trever Lieutenant Commander William H. Shea, Jr. (1936)LANDING CRAFT FLOTILLAS, SOUTH PACIFIC FORCE

Commander Landing Craft Flotillas Chief of Staff Rear Admiral George H. Fort (1912) Captain Benton W. Decker (1920) _LST Flotilla Five_--Captain Grayson B. Carter (1919) _LST Group Thirteen_--Commander Roger W. Cutler, USNR LST Division 25 LST-446 (GF) Lieutenant Robert J. Mayer, USNR

LST-447 Lieutenant Frank H. Storms, USNR

LST-448 Ensign Charles E. Roeschke, USN

LST-449 Lieutenant Laurence Lisle, USNR

LST-460 Lieutenant Everett E. Weire, USN

LST-472 Lieutenant William O. Talley, USN LST Division 26 LST-339 Lieutenant John H. Fulweiler, USNR

LST-340 Lieutenant William Villella, USN

LST-395 Lieutenant Alexander C. Forbes,USNR

LST-396 Lieutenant Eric W. White, USN

--504--

LST-397 Lieutenant Nathaniel L. Lewis, USNR

ST-398 Lieutenant Boyd E. Blanchard, USNR _LST Group Fourteen_--Commander Paul S. Slawson (1920) LST Division 27 LST-341 Lieutenant Floyd S. Barnett, USN

LST-342 Lieutenant Edward S. McCluskey, USNR LST Division 28 LST-353 Lieutenant Luther E. Reynolds, USNR

LST-354 Lieutenant Bertram W. Robb, USNR LST Group Fifteen LST Division 29 LST-343 Lieutenant Harry H. Rightmeyer, USN

LST-399 Lieutenant George F. Baker, USN _LCI(L) Flotilla Five_--Commander James McD. Smith (1925) _LCI(L) Group Thirteen_--Lieutenant Commander Marion M. Byrd (1927) LCI Division 25 LCI-61 Lieutenant John P. Moore, USNR

LCI-62 Lieutenant (jg) William C. Lyons, USN

LCI-63 Lieutenant (jg) John H. McCarthy, USNR

LCI-64 Lieutenant Herbert L. Kelly, USNR

LCI-65 Lieutenant (jg) Christopher R. Tompkins, USNR

LCI-66 Lieutenant Charles F. Houston, Jr., USNR LCI Division 26 LCI-21 Ensign Marshall M. Cook, USNR

LCI-22 Lieutenant (jg) Spencer V. Hinckley, USNR

LCI-67 Lieutenant (jg) Ernest E. Tucker, USNR

LCI-68 Lieutenant Clifford D. Older, USNR

LCI-69 Lieutenant Frazier L. O'Leary, USNR

LCI-70 Lieutenant (jg) Harry W. Frey, USNR _LCI(L) Group Fourteen_--Lieutenant Commander Alfred V. Jannotta, USNR LCI Division 27 LCI-327 Lieutenant (jg) North W. Newton, USNR

LCI-328 Lieutenant Joseph D. Kerr, USNR

LCI-329 Lieutenant William A. Illing, USNR

LCI-330 Lieutenant (jg) Homer G. Maxey,USNR

LCI-331 Lieutenant Richard O. Shelton, USNR

LCI-332 Lieutenant William A. Neilson, USNR LCI Division 28 LCI-23 Lieutenant Ben A. Thirkfield, USNR

LCI-24 Lieutenant (jg) Raymond E. Ward, USN

LCI-333 Lieutenant Horace Townsend, USNR

LCI-334 Lieutenant (jg) Alfred J. Ormston, USNR

--505--

LCI-335 Lieutenant (jg) John R. Powers, USNR

LCI-336 Lieutenant (jg) Thomas A. McCoy, USNR _LCI(L) Group Fifteen_--Commander James McD. Smith (1925) LCI Division 29 LCI-222 Ensign Clarence M. Reese, USNR

LCI-223 Lieutenant Frank P. Stone, USNR _LCT(5) Flotilla Five_--Lieutenant Commander Paul A. Wells, USNR _LCT Group 13_--Lieutenant Ashton L. Jones, USNR _LCT Division 25_--Lieutenant Ashton L. Jones, USNR LCT-58 Ensign James E. Jones, USNR

LCT-60 Boatswain John S. Wolfe, USN

LCT-156 Ensign Harold Mantell, USNR

LCT-158 Ensign Edward J. Ruschmann, USNR

LCT-159 Ensign John A. McNiel, USNR

LCT-180 Ensign Sidney W. Orton, USNR _LCT Division 26_--Lieutenant Ameel Z. Kouri, USNR LCT-62 Ensign Robert T. Capeless, USNR

LCT-63 Ensign Joseph R. Madura, USNR

LCT-64 Ensign Kermit J. Buckley, USNR

LCT-65 Ensign Grant L. Kimer, USNR

LCT-66 Ensign Charles A. Goddard, USNR

LCT-67 Ensign William H. Fitzgerald, USNR _LCT Group 14_--Lieutenant Decatur Jones, USNR _LCT Division 27_--Lieutenant Decatur Jones, USNR LCT-321 Ensign Robert W. Willits, USNR

LCT-322 Ensign Frederick Altman, USNR

LCT-323 Ensign Carl T. Geisler, USNR

LCT-324 Ensign David C. Hawley, USNR

LCT-325 Ensign John J. Crim, USNR

LCT-326 Ensign Harvey A. Shuler, USNR LCT Division 28 LCT-367 Ensign Robert Carr, USNR

LCT-369 Ensign Walter B. Gillette, USNR

LCT-370 Ensign Leonard M. Bukstein, USNR

LCT-375 Richard I. Callomon, USNR

LCT-376 Lieutenant (jg) Francis J. Hoehn, USNR

LCT-377 Ensign THomas J. McGann, USNR _LCT Group 15_--Lieutenant Frank M. Wiseman, USNR _LCT Division 29_--Lieutenant Frank M. Wiseman, USNR LCT-181 Lieutenant (jg) Melvin H. Rosengard, USNR

LCT-182 Ensign Jack E. Johnson, USNR

--506--

LCT-327 Ensign James L. Caraway, USNR

LCT-330 Ensign Leon B. Douglas, USNR

LCT-351 Ensign Robert R. Muehlback, USNR

LCT-352 Lieutenant (jg) Winston Broadfoot, USNR _LCT Division 30_--Lieutenant (jg) Picket Lumpkin, USNR _LCT-68_Ensign Edward H. Burtt, USNR

LCT-69 Ensign Austin N. Volk, USNR

LCT-70 Ensign C.M. Barrett, USNR

LCT-71 Ensign Richard T. Eastin, USNR

LCT-481 Ensign George W. Wagenhorst, USNR

LCT-482 Boatswain Herbert F. Dreher, USN _LCT(5) Flotilla Six_--Lieutenant Edgar M. Jaeger, USN _LCT(5) Group 16_--Lieutenant Wilfred C. Margetts, USNR _LCT Division 31_--Ensign Robert A. Torkildson, USNR LCT-126 Ensign Philip A. Waldron, USNR

LCT-127 Ensign Robert A. Torkildson, USNR

LCT-128 Ensign Joseph Joyce, USNR

LCT-129 Ensign Emergy W. Graunke, USNR

LCT-132 Ensign Milton Paskin, USNR

LCT-133 Ensign Bertram Meyer, USNR _LCT Division 32_--Lieutenant (jg) Donald O. Kringel, USNR LCT-134 Ensign James W. Hunt, USNR

LCT-139 Ensign Ralph O. Taylor, USNR

LCT-141 Lieutenant (jg) Donald O. Kringel, USNR

LCT-144 Ensign E.B. Letz, USNR

LCT-145 Ensign Willard E. Goyette, USNR

LCT-146 Ensign William W. Asper, USNR _Coastal Transport Flotilla Five_--Lieutenant D. Mann, USNR _APc Division 25_--Lieutenant Dennis Mann, USNR APc-23 (F) Lieutenant Dennis Mann, USNR

APc-24 Lieutenant Bernard F. Seligman, USNR

APc-25 Lieutenant John D. Cartano, USNR

APc-26 Ensign James B. Dunigan, USNR

APc-27 Lieutenant Paul C. Smith, USNR

APc-28 Lieutenant (jg) Austin D. Shean, USNR _APc Division 26_--(provisional) Lieutenant Arthur W. Bergstrom, USNR APc-37 (F) Lieutenant James E. Locke, USNR

APc-29 Lieutenant (jg) Eugene H. George, USNR

APc-35 Lieutenant Robert F. Ruben,USNR

APc-36 Lieutenant (jg) Kermit L. Otto, USNRAll of the above amphibious units were in the initial echelons of TOENAILS except for LST Division 25 (minus LST-472, which did participate),LCI-32 and LCTs 68 thru 71 and _LCT-321._The latter arrived Tulagi

--507--

Colonel Henry D. Linscott, USMC, Assistant Chief of Staff, Commander Amphibious Force South Pacific, in front of his tent at Camp Crocodile, Guadalcanal, late Spring, 1943.

(Courtesy of Major General Frank D. Weir, USMC (Ret.))Harbor on 16 July 1943, and was logged in as "the newest arrival this area, " and together with LST-475, LCTs 68, 69, 70, and a number of APc's participated in later phases of the South Georgia Group operations.

At the time the TOENAILS movement to the New Georgia Group began, there were 11 LSTs, 23 LCIs, 35 LCTs and 10 WATCHTOWER's (coastal transports) from Flotilla Five and Flotilla Six available in PHIBFORTHIRDFLT. On D- Day nearly all of these were either unloading in the Middle Solomons or loaded in the Guadalcanal-Russell Island area and waiting for orders.

During the month before TOENAILS was kicked off, the Landing Craft Flotillas were far from idle. They delivered 23,775 drums of lubricants and fuel, 13,088 tons of miscellaneous gear and 28 loaded vehicles to the Russell Islands alone. All cargo requirements for the TOENAILS Operation were loaded by 22 June 1943.

In this connection, Lieutenant General Linscott, who had been the very skillful and highly appreciated Assistant Chief of Staff for the Commander

--508--

Amphibious Force South Pacific during its very critical first year of existence, wrote:

I feel that Commodore L.F. Reifsnider should receive some recognition for handling the 'Guadalcanal Freight Line' after Admiral Turner moved north from Noumea. These duties were in addition to his assignment as Commander Transport Group, South Pacific. His principal assistants were Commander John D. Hayes, Lieutenant Colonel W.B. McKean (who acted as Operations Officer) and Commander 'Red' [W.P.] Hepburn. All should be recognized for the effective manner in which they handled the task.27

First Move on the TOENAILS Checkerboard

As April inched into May, and D-Day for TOENAILS began to assume reality, it became apparent that Rear Admiral Turner would be on top of his job much better if he were personally located at Koli Point, Guadalcanal, where a large part of the Expeditionary Force was starting to gather, rather than at Noumea 840 miles to the southward and subject to all the delays and vagaries of encrypted radio communications.

The volume of radio traffic had steadily increased as the number of amphibious ships steadily increased, and traffic delays of 10, 12 and more hours for "operational" traffic were usual. Events were flowing far faster than the radio traffic.

In mid-May it was planned that on 27 May 1943, Rear Admiral Turner as CTF 32 and the McCawley as a unit of TU 32.8.2 which would consist of four transports, five merchant cargo ships, six motor torpedo boats, two small patrol craft and seven escorting destroyers, would depart from Noumea for Koli Point, Guadalcanal, which, with the Russell Islands, were to be used as staging points for TOENAILS. Task Unit 32.8.2 would carry a Marine Raider Battalion, three naval construction battalions, a coast artillery regiment and other smaller detachments. Upon arrival at Koli Point, Rear Admiral Turner and the operational staff would shift their headquarters ashore.28

However, as the 27 May departure date drew near, it was decided to sail the large Navy transports separately from the merchant ships, the latter sailing first. Thus, the date for the separation of Rear Admiral Turner from the ear of Vice Admiral Halsey was postponed until 7 June 1943.

--509--

Officers' Quarters at Camp Crocodile, Guadalcanal, late Spring, 1943.(Courtesy of Capt. Charles Stein, USN (Ret.))Just before departure on 7 June, Rear Admiral Turner came down with malaria, and the doctors insisted on transferring him to the hospital ship Solace. His temporary separation from active command of Task Force 32 and Task Unit 32.8.2 is referred to in the War Diary of his command only in these terms "Rear Admiral Turner was detained in Noumea." According to an author who was in the South Pacific at the time: <blockquote< i=""> </blockquote<>

Admiral Turner was a sick man before the New Georgia campaign started; he 'shoulda stood in bed,' as they say in the Bronx. A fortnight before D-Day, he was stricken with malaria and dengue fever and hoisted aboard the hospital ship Solace. . . .29

Rear Admiral Anderson, Turner's Chief of Staff at the time, remembered:

--510--

Admiral Turner did not sail in the McCawley up to Guadalcanal just prior to the New Georgia Operation. He became suddenly sick with both dengue fever and malaria and went aboard the hospital ship Solace then anchored in Noumea Harbor. He was a patient there for over a week. I went out to see him every forenoon and took him important despatches and correspondence for him to read. On several successive days he asked me to bring out to him a bottle of liquor. I wouldn't do it. Several times he really begged me to do it.30

Commander Landing Craft Flotillas recalls:

[Turner's] health was apparently good until just before 'Toenails, ' when he was at Noumea planning the operation with General Hester. I was in Guadalcanal when I was informed that Turner was on the hospital ship in Noumea with both malaria and dengue fever. I was somewhat worried that I might be called upon to do that show, being No. 2 at that time, with no preparation at all. However, he bobbed up serenely and got up to Guadalcanal just in time. . . .31

Administration of Task Force 32 during this period when Rear Admiral Turner was busy in Guadalcanal was to be exercised by Captain A.B. Anderson, Chief of Staff, CTF 32, who with a small portion of the staff would remain in Noumea at the Administrative Headquarters of Commander Landing Craft Flotillas, Third Fleet (Rear Admiral George H. Fort).

Rear Admiral Anderson, in 1962, recalled:

I set up the office in two quonset huts in the city. One was used to house part of the enlisted personnel. I, with Morck [Flag Secretary] moved into a house on the outskirts of Noumea formerly used by George Fort and Benny Decker [who] stayed with us for a couple of weeks, then went afloat.

The McCawley, with other ships of the Force, was to pick up troops and train them in forward areas preparatory to the New Georgia Operation. Admiral Turner saw no reason for a number of officers and a large clerical force to be in the flagship when space was required for personnel of the Landing Force. Also, when the flagship was away, he wanted an office in Noumea to handle the day to day things that came up. Shipments of landing craft were arriving and he wanted them indoctrinated and trained before being sent forward. Admiral Fort had already gone forward with some of his Flotilla. Benny Decker (his C/ S) was left in Noumea to train new additions. I was to work with him on this.32

While enroute to Guadalcanal on 10 June, 1943, TU 32.8.2 made up of five transports with six destroyers to guard them, and under the command

--511--

of Captain Paul Theiss, Commander Transport Division 14 in the President Jackson, was harassed by Japanese snooper planes for six hours. It was attacked by seven Japanese bombing planes at deep dusk and again, after a half moon dark, with flares (luckily faulty) dropped to aid the planes. No ships were hit due to the well-timed and continuous radical maneuvering of the Task Unit, executed for two hours in the best Turner tradition, and by the heavy anti-aircraft fire of the destroyers.33

The Rehearsal

When Rear Admiral Turner arrived in Guadalcanal from the Solace, the day after a big Japanese air raid, Task Force 31 took over the TOENAILSinvasion task from Task Force 32 and was promptly formed up at 1500 on 17 June 1943 with 12 LSTs, 12 LCIs, 28 LCTs, 10 APc's, three APDs, two DM's, and two ATs. The number of ships and landing craft assigned to Task Force 31 increased daily thereafter; Task Force 32 continued with shrinking strength to accomplish general administrative and support tasks.

The large majority of landing ships and landing craft for the TOENAILSOperation trained for their forthcoming operation in the Guadalcanal- Tulagi- Russell Islands area, but there was no overall dress rehearsal for TOENAILSwith air support, gunfire support ships, and the large transports present. This omission of an overall dress rehearsal was a violation of the Amphibious Doctrine, as well as the lesson of WATCHTOWER which showed considerable advantage could be gained from a dress rehearsal. In trying to run down why there was no full-scale dress rehearsal for TOENAILS, the written record is scanty, and memories pretty dim. It seems that the Staff believed the danger from alerting the Japanese to the nearness of an invasion, should they detect the rehearsal from an unusually heavy volume of radio traffic, was greater than the danger from the loss of coordinated training.34

When Vice Admiral George H. Fort, USN (Retired), who was Second- in- Command of the Amphibious Forces in TOENAILS, was asked the question "Why didn't TOENAILS have a dress rehearsal?," his reply was, "Where would you have held it?" and later, "We seldom had a [full-scale] rehearsal in those days, having neither the ships or troops available until the last minute."35

--512--

The rehearsal by the large transports for the TOENAILS Operation was held at Fila Harbor, Efate, in the New Hebrides, 560 miles to the southeast from Guadalcanal. This harbor area was quite acceptable since preparatory ships' gunfire was not required for the TOENAILS Operation. The large transports arrived at Efate on 16 June 1943, and remained there for ten days of training and rehearsal. This training was prescribed on 29 May 1943 when CTF 32 issued his Movement Order A7-43.

The large transports for the operation did not arrive up at Guadalcanal until 10:00 on the 29th, when they were reassigned from Task Force 32 to Task Force 31.

The decision not to have the large transports in the Guadalcanal area in the first part of June proved an extremely wise one when the Japanese swept over the Iron Bottom Sound area, on 7, 12, and 16 June, with from 40 to 60 bombers and their escorting fighters. The last of these three raids hit and burned out the LST-340 and the Celeno (AK-76).

The War Diary of LST-340 for the 16 June incident included the following flesh and blood account by a newly trained amphibian:

Another Condition Red came by radio. Each one scrambled into his life jacket and helmet and made for his battle station. Those were tense moments. The blood in one's very veins turned cold. There were many scared people. . . .

In the evening to quiet the nerves of the bombed and fire weary sailors and officers, there was a beer party staged just off the ramp of the burned ship. It was for the personnel who participated in the disaster which befell the 340. . . .36

The Japanese surprisingly enough failed to pay a daily complimentary bombing visit to the staging areas of Guadalcanal and the Russells during the last two weeks before TOENAILS.

The late arrival at Guadalcanal of these large transports was purposeful even though it led to some grousing on the part of troops, Seabees and naval base personnel who had to be loaded aboard the transports with marked speed on Dog Day minus one. It was an effort to shorten the interval between the time Japanese air might sight and report these large transports, the Japanese high command might sense an invasion effort and start the Japanese Combined Fleet south from Truk, and when the transports would necessarily arrive in the New Georgia Group.37

By keeping the large transports out of the staging areas until the day

--513--

before the invasion, it is logical to assume that Rear Admiral Turner had deceived the Japanese of the imminence of the New Georgia effort, if not its immediate objectives. Conclusions in regard to the objective logically could have been drawn from our almost daily bombings of Munda and Vila airfields. (Munda was bombed on four out of five days and Vila on three out of five days beginning on 25 June, while no other base in the Central or Northern Solomons, i.e. Rekata Bay, Kahili, Ballale or Buka, was bombed more than twice.)38

The SOPAC Final TOENAILS Plan

The general concept of Vice Admiral Halsey's plan was that movements of the amphibians on 30 June 1943 into the New Georgia Group were the necessary prelude to capturing in succession Munda airfield on New Georgia, Vila airfield on Kolombangaru, and other enemy positions in the New Georgia Group.39

The only deadlines set by COMSOPAC were 30 June when the initial amphibious landings were to take place, and following which, at "any favorable opportunity," a flank assault on Munda airfield was to be launched, by landing at Zanana Beach on New Georgia, five miles east of Munda.

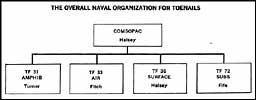

Vice Admiral Halsey's Operation Plan 14-43 divided the forces available to him for TOENAILS into four main segments and directed that the surface, air, and submarine elements would all support the amphibious element, which Rear Admiral Turner would command.

Specifically, the three elements supporting the amphibious forces were:

--514--

- Task Force 33 which under Vice Admiral Aubrey Fitch controlled all the land based aircraft and tender based aircraft in the South Pacific Area.

- Task Force 36 which under Vice Admiral Halsey's own command and coordination consisted of (1) two Carrier Task Groups, (2) three surface ship task groups, one including fast minelayers and (3) the Ground Force Reserve, and

- Task Force 72 which under Captain James Fife, provided eleven submarines from the Seventh Fleet based on Australia.

Task Force 33, the SOPAC Air Force, was directed to:

- Provide reconnaissance air cover and support.

- Neutralize enemy air flying out from the New Georgia Group and Bougainville.

- Arrange with and provide CTF 31 with air striking groups for use in the immediate vicinity of TF 31.

Task Force 36, the Covering Force, was directed to "destroy enemy forces threatening TOENAILS Operation."

Task Force 72, the Submarine Force, was directed to:

- "Conduct offensive reconnaissance" near the equator and north of the Bismarck Archipelago, and

- Cover the channels between Buka, New Ireland, and Bougainville.

Task Force 36 was divided into six Task Groups with a Flag or General officer heading up each group.

As CTG 36.1, Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth (1910) in the Honolulu(CL-48) had CRUDIV Nine and five destroyers.

As CTG 36.2, Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill (1912) in the Montpelier(CL-57) had CRUDIV 12, five destroyers, and three fast minelayers.

As CTG 36.3, Rear Admiral DeWitt C. Ramsey (1912) in the Saratoga (CV-3) had three battleships, two anti-aircraft light cruisers, 14 destroyers and the British carrier Victorious as well as an oiler.

As CTG 36.4, Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill (1911) had two battleships from Battleship Division Four, and four destroyers.

As CTG 36.5, Rear Admiral Andrew C. McFall (1916) in the Sangamon (CVE-26) had Carrier Division 22 (three escort carriers) and six destroyers.

As CTG 36.6, Major General Robert S. Beightler, U.S. Army, had the 37th Division less two regimental combat teams.

Task Force 33 contained somewhere between 530 and 625 planes, the exact number on 30 June being difficult to determine. However, on 30 June,

--515--

Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher who under Vice Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, Commander TF 33 and Air Force South Pacific, commanded the Solomon Islands Air Force, reported that 455 planes in his Force were ready to fly. These were 213 fighters, 170 light bombers and 72 heavy bombers. In contrast, the Japanese at Rabaul had but 66 bombers, and 83 fighter aircraft on this day, with an undetermined small number at Buka, Kahili, and Ballale, their three main operational airfields in the Northern Solomons.40

The main submarine unit of Task Force 72, commanded by Captain James Fife (1918), was Submarine Squadron Eight, commanded by Captain William N. Downes (1920). Captain Downes acted as Liaison Officer to Commander Third Fleet and was positioned in Noumea from the latter part of June until mid-July 1943. Six to eight submarines of this squadron were on station in the Solomons from mid-June to mid-July.

For Dog Day, the carrier task force was told to operate in an area nearly 500 miles south of Rendova--well out of range for any close air support and well clear of enemy shore based air.

One cruiser-destroyer force was assigned an operating area 300 miles south-southwest of Rendova, while another cruiser-destroyer-minelayer force was given the chore of laying a minefield 120 miles north of Rendova and bombarding various airfields north of New Georgia.

The planes from the escort aircraft carriers called "jeep" carriers41were to be flown off to augment the shore-based aircraft of CTF 33, COMAIRSOPAC. One division of battleships was kept in a 2-hour ready status in far away Efate, 750 miles from the New Georgia objective.

AIRSOPAC would provide the aircraft umbrella, and the submarines would provide any unwelcome news of the approach of major units of the Japanese Fleet towards or past the Bismarck Barrier.

It should be noted that COMSOPAC's Plan:

- provided that a shore-based commander, Vice Admiral Halsey, retained immediate personal control of the operation.

- did not provide for the coordination of the various SOPAC task forces under one commander in the operating or objective area, should a Japanese surface or carrier task force show up to threaten

--516--

The Admiral's Head, Camp Crocodile, Guadalcanal Island.(Courtesy of Capt. Charles Stein, USN (Ret.))or attack the amphibious force, i.e., did not provide an Expeditionary Force Commander.

- Did not provide any aircraft under the control of the Amphibious Task Force Commander for dawn or dusk search of the sea approaches immediately controlling the landing areas.

- Did not provide in advance the conditions for the essential change of command from the Amphibious Task Force Commander to the Landing Force Commander, merely stating: "The forces of occupation

--517--

in New Georgia Island will pass from command of CTF 31 on orders from COMSOPAC."

COMSOPAC's Plan did provide for:

- Air striking groups, under the control of the amphibious task force commander, for use in the immediate vicinity of that Force.

- Commander Amphibious Force having the authority to ensure "coordination of detailed plans in connection with the amphibious movement and the immediate support thereof."

- Broadcast of evaluated information on two circuits (SOPAC Love and NPM Fox).

- An Air Operational Intelligence circuit to retransmit contact reports received from reconnaissance aircraft.

- Stationing of submarine units to detect and report southward movement of Japanese surface forces from Truk or entering the northern waters of the Slot, in an effort to alert the amphibious forces to the approach of any heavy units from the Combined Fleet.

COMAIRSOPAC moved his operational headquarters to Guadalcanal on 25 June so that in the period immediately prior to the launching of the invasion forces he would be working in the same headquarters as the amphibious commander.

So at least some major steps were taken to prevent another Savo Island.

A Larger Staff

By the time of the TOENAILS Operation, the PHIBFORSOPAC Staff had expanded from 11 to 16 officers, and there were many new faces, including two majors from the United States Army. 21 additional officers were attached to the Staff in supporting roles mainly in the Communication and Intelligence areas.

On 8 May 1943, nine days before Vice Admiral Halsey issued his directive for the TOENAILS Operation, Rear Admiral Turner requested Lieutenant General Harmon to order five officers of the 43rd Division to report to COMPHIBFORTHIRDFLT for the preparation of the plans for TOENAILS, and suggested that these officers plan on living aboard the flagship_McCawley._42This was done. The names of these officers are not shown below, as this was a temporary detail only.

--518--

Lieutenant Colonel Frank D. Weir, USMC, Assistant Operations (Air), before his tent at Camp Crocodile, Guadalcanal.(Courtesy of Maj. Gen. F.W. Weir, USMC (Ret.))STAFF OF COMMANDER AMPHIBIOUS FORCE, SOUTH PACIFIC (COMPHIBFORTHIRDFLT)

| Chief of Staff | | Captain A.B. Anderson, USN (1912) | | ----------------------------------------- | | ----------------------------------------------- | | Assistant Chief of Staff | | Colonel H.D. Linscott, USMC (1917) | | Operations Officer | | Captain J.H. Doyle, USN (1920) | | Assistant Operations Officer (Air) | | Colonel F.D. Weir, USMC (1923 | | Communications Officer | | Commander G.W. Welker, USN (1923) | | Assistant Operations Officer (Aerologist) | | Commander W.V. Deutermann, USN (1924) | | Gunnery Officer | | Commander D.M. Tyree, USN (1925) | | Medical Officer | | Commander R.E. Fielding (MC), USN (1928) | | Aide and Flag Secretary | | Commander Hamilton Hains, USN (1925) | | Assistant Flag Secretary | | Lieutenant Commander Carl E. Morck, USNR (1929) |

--519--

Aide and Flag Lieutenant } Lieutenant Commander J.S. Lewis, (USN) 1932) Assistant Operations Officer Intelligence Officer Major F.A. Skow (CE), AUS Transport Quartermaster Major W.A.Neal, USMCR Assistant Operations Officer Major A.W. Bollard (GSC), USA Assistant Communications Officer Major R.A. Nicholson, USMCR Supply Officer Lieutenant C. Stein, Jr., (SC) USN (1937) OFFICERS ATTACHED TO STAFF FOR SPECIAL DUTIES

| Captain John E. Merrill, USMCR | | Assistant Intelligence Officer | | ------------------------------------------- | | ------------------------------ | | Captain Richard A. Gard, USMCR | | Assistant Intelligence Officer | | Lieutenant Leo M. Doody, USNR | | Assistant Gunnery Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) Leonard te Groen, USNR | | Assistant Flag Secretary | | Lieutenant (jg) Jeff N. Bell, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) August J. Garon, USNR | | Assistant Intelligence Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) George G. Gordon, USNR | | Assistant Intelligence Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) Clifford R. Humphreys, USNR | | Assistant Operations Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) Henry I. Cohen, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) Roger S.Henry, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) Howard H. Braun, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) Thomas A. Dromgool, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Lieutenant (jg) William C. Powell, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Ensign John P. Hart, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Ensign Gordon N. Noland, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Ensign Harry D. Smith, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Ensign John G. Feeley, USNR | | Communication Watch Officer | | Radio Electrician Paul L,. Frost, USN | | Radio Electrician |

Staff rosters available from March 1943 to July 1943 indicate that Captain Anderson, Lieutenant Commander Morck, Lieutenant (junior grade) John C. Weld, USNR and Acting Pay Clerk Melvin C. Amundsen were assigned with the Administrative Command at Noumea, New Caledonia, during this period. Lieutenant (junior grade) Henry D. Linscott, Jr., USNR, one of the Assistant Operations Officers, was temporarily with the Guadalcanal Freight Line on the Staff of Commodore Lawrence F. Reifsnider, and Lieutenant Leo W. Doody, USNR, was away on temporary duty in connection with gunfire support training. Consequently only 32 of the 38 officers (including Rear Admiral Turner) were available when the Staff picture was taken. 30 of these 32 appear in the picture.

All 15 members of the regular Staff quartered on Guadalcanal have been positively identified by three or more of its present living members. Of the

--520--

Front Row, Left to Right: (1) Lieutenant Colonel Frank D. Weir, USMC (2) Colonel Henry D. Linscott, USMC (3) Rear Admiral R.K. Turner, USN (4) Captain James H. Doyle, USN (5) Commander George W. Welker, USN.

Second Row, Left to Right: (6) Radio Electrician Paul L. Frost, USN (7) Commander William U. Deutermann, USN (8) Lieutenant Commander John S. Lewis, USN (9) unidentified (1) Major Robert A. Nicholson, USMCR (11) Lieutenant Charles Stein (SC), USN (12) unidentified (13) Commander David M. Tyree, USN (14) Commander Ralph E. Fielding (MC, USN (15) Major Arthur W. Bollard, AUS (16) Captain J.C. Erskine, USMCR

Subsequent Rows, Left to Right: (17) Lieutenant (jg)Z George G.Gordon, USNR (18) Ensign Harry D. Smith, USNR (19) unidentified (20) Major Willis A. Neal, USMCR (21) Ensign Thomas A. Dromgool, USNR (22) Commander Hamilton Hains, USN (23) Major Floyd Skow (CE), AUS (24) Lieutenant (jg) Howard H. Braun (?) (25) unidentified (26) Lieutenant (jg) Leonard te Groen (27) Lieutenant (jg) Jeff N. Bell, USNR (28) Captain Richard A. Gard (29) Captain John E. Merrill (3) Lieutenant (jg) Roger S. Henry (?)(Turner Collection)

--521--

15 other officers in the picture six: Captain John C. Erskine, USMCR, whom Merrill relieved, Gard, Gordon, Smith, Dromgrool, and Bell, have been identified by two or more members. Three more: Braun, te Groen, and Henry have been identified or guessed at by one or more members. Numbers 9, 12, 19, and 25 in the photograph have not been identified.

One Marine officer, Captain Gard, was placed in three different positions, before he was located in Hong Kong and identified himself.

Amphibious Force General Plan

The amphibious plan changed a number of times as the information or intelligence brought in by the reconnaissance patrols in regard to the New Georgia Group expanded or changed. To a marked extent, the Scheme of Maneuver agreed upon by Rear Admiral Turner and Major General Harmon and later by Major General Hester was determined by such hard physical facts as depth of water, reefs, beach gradients, numbers of troops or amounts of supplies which could be landed on narrow beaches, possible beach exits into dense jungle, jungle trails, jungle clearings, or possible bivouac areas.43

A major problem with the new large landing craft (LSTs and LCTs) was in finding beach gradients where they could land their cargo through the bow doors, and in finding breaks in the mile-long reefs. Munda Bar was another mental and physical hazard which tempered a desire to make a frontal attack on the airfield as had been done at Guadalcanal. Older British charts dating back to 1900 had shown three to seven fathoms over Munda Bar which would have permitted comfortable passage by destroyer-type fast transports and large landing craft, but more recent reports cast doubt on these depths and the best information was that there was only an unmarked 300-foot wide passage over the bar with 18 feet of water at high tide and 15 feet at low tide.44

Major discussion during the early part of the long planning period before Vice Admiral Halsey issued his Op Plan 14-43 centered on:

- whether a frontal assault on Munda could be attempted.

- the provision of close air and gun support during the first couple of days of an assault landing.

Close air support by land-based planes directly from Guadalcanal was

--522--

difficult to impossible because of the distance 180 miles. Close air support from the Russells, 125 miles away, was limited by there being room for only two airstrips on Banika Island in the Russells.

The Third Fleet Commander, Vice Admiral Halsey, was reluctant to maintain carriers in a position to provide a major portion of such close air support over a period of more than two or three days. His position in this apparently was no different than Vice Admiral Fletcher's had been prior to and during the WATCHTOWER landings.

As the CINCPAC planners wrote in their estimate of the situation:

A frontal landing from the south would require landing craft to approach through openings in the coral reef which can be covered easily from ashore, and which are narrow so as to prevent a broad approach.

The Amphibious Force Commander was reluctant to test his large landing craft over Munda Bar, in their first assault landing, and the Landing Force Commander was reluctant to give a firm guarantee of success for a frontal assault against Munda airfield within the short period of two to three days.

As soon as the decisions were made that neither the fast carrier task forces nor the jeep carriers would provide close air support for TOENAILSand that the amphibians would not risk an initial all out frontal assault over Munda Bar, an alternative plan was evolved and accepted by all hands.

This plan included making the major assault on Munda airfield from its eastern flank while simultaneously landing a holding assault against its seaward (southern) front and closing off its support lines to the north by a small landing on Kula Gulf. The plan also provided for building an airstrip at Segi Point, New Georgia, to provide close air support for the impending assault on Vila airstrip, and the making of Rendova Island into a combination staging point and artillery support position for the Munda assault.

Thus the Navy was relieved of the night time hazards of Munda Bar and the inhospitable coral-studded approaches to Munda Point beaches, and the Army of an assault without some semblance of its own artillery support. But the plan was not a prescription for quick victory.

The limited experience of CLEANSLATE had indicated that the tank landing craft, with their small crews, frequent breakdowns and slow speed in even moderate weather, required ports or protected anchorages at about 60-mile intervals where they could receive repairs and daytime rest, while they approached the landing beaches at night. This led to a search for protected harbors or anchorages in the Middle Solomons and to the selection

--523--

of Viru Harbor, New Georgia, and Wickham Anchorage, at the eastern approaches to Vangunu Island, as areas to be seized.

Viru Harbor was, in the early planning, also a location where sizable forces could be profitably and safely disembarked from landing ships and then moved by small landing craft closer to Munda to assist in the flank assault on Munda airfield. Segi Point was selected because it was the only area where a fighter strip might be built to assist in the assault on Vila airfield or even on Munda, if success there was long delayed.

The small contingent of Japanese troops at Viru and Wickham, in each case, was a magnet as well. If the Japanese needed these locations to control and safeguard the islands, then we might need them also.

Rice Anchorage, upon Kula Gulf, almost directly north of Munda, was selected as the location where the troops whose task would be to seal off the northern flank of Munda would be landed.

Assigning the Tasks

The amphibians had one major task and four minor ones to accomplish the morning of 30 June, and a further task four or more days later.

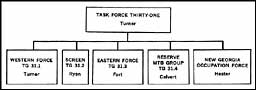

Rear Admiral Turner divided the amphibious assault force of Task Force 31 into two major groupings for 30 June. The division was based on whether the tasks were to be accomplished in the eastern or western part of the New Georgia Group. Appropriately, he labeled them the Eastern Force and the Western Force.

The Rice Anchorage Landing Group was separately organized using the destroyer type transports and minesweepers assigned to the 30 June landings. It was called the Northern Landing Group.

CTF 31 (Rear Admiral Turner) retained immediate command of Task

--524--

Group 31.1, an organization of all the large transports and cargo ships, part of the destroyer-type transports and minesweepers, most of the larger landing craft (LSTs) and the necessary protecting destroyers. Rear Admiral Turner assigned his senior subordinate, Commander Landing Craft Flotillas, Rear Admiral George H. Fort (1912), to command Task Group 31.3, an organization of destroyer- type transports and minesweepers, infantry and tank landing craft and coastal transports.

Task Group 31.1, which in violation of Naval War College doctrine for terminology, was named the Western Force instead of the Western Group, with Commander Transport Division Two, Captain Paul S. Theiss (1912), as Second in Command, was assigned the Rendova Island task.

Task Group 31.3 which was erroneously named the Eastern Force instead of the Eastern Group, with no designated Second-in-Command, was assigned the three assault chores at (1) Viru Harbor, New Georgia, (2) Segi Point, New Georgia, and (3) at Wickham Anchorage which lies between Vanguna and Gatukai Islands, the first two large islands to the southeast from New Georgia. These three places all could serve as first aid stations for tank landing craft or PT boats making the run from the Russells to Rendova or Munda.