The Genus Xylaria (MushroomExpert.Com) (original) (raw)

The Genus Xylaria

[ Ascomycota > Sordariomycetes > Xylariales > Xylariaceae . . . ]

by Michael Kuo

The genus Xylaria consists of funky, club-like decomposers of wood or plant debris that become black and hard by maturity, reminiscent of carbon or charcoal. The mushrooms are "Pyrenomycetes," which means they produce spores in asci that are embedded in tiny pockets called perithecia; the asci take turns growing into the narrow opening of the pocket so that they can shoot spores away from the fungus and into the air currents.

The Xylaria life cycle gets a little complicated, and the complications can make precise identification of one's Xylaria collections difficult. Like many fungi, Xylaria species hedge their reproductive bets by engaging in both sexual and asexual reproduction. The spores, asci, and perithecia mentioned above occur when the fungus is mature, and reproducing sexually. In its immature, asexual stage, a Xylaria produces asexual spores, officially called "conidia," in a powdery coating (morel hunters frequently encounter the conidial stage of Xylaria polymorpha in late spring).

This is all well and good for the Xylaria, but more than a little problematic for would-be Xylaria identifiers, since the various species are usually separated on the basis of the morphology of their (sexual) spores. Thus, if you have collected a Xylaria in its asexual, conidial stage, you will be missing the most important morphological character for identification (the conidia, in case you're wondering why they can't substitute for spores in the identification process, tend to look more or less the same)—that is, unless you have a mycological laboratory and the ability to culture your collection; the species can actually be identified on the basis of the way the cultures look and act in the petri dish (see Callan & Rogers, 1993).

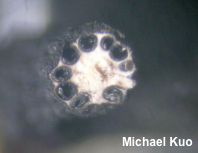

Most of us, however, lack the ability to culture our collections, which means we can only accurately identify mature, sexual forms. In the field, these can often be recognized by the presence of perithecia, which look like tiny pimples (use a hand lens). Collectors in north-temperate regions can also employ the strategy of not collecting Xylaria specimens in spring and early summer, when asexual forms are more prominent.

Even with identifiable specimens in hand, there is no getting around the fact that microscopic analysis is frequently necessary for accurate Xylaria identification—which leads many collectors to label their collections of fat specimens "Xylaria polymorpha" and their skinny collections "Xylaria hypoxylon," since these are species frequently included in field guides. This is not an unreasonable strategy if your identification goals are casual, but if you have a penchant for accuracy you will need to consult pyrenomycete expert J. D. Rogers's key to Xylaria in the continental United States (1986; full citation below).

Xylaria species are not particularly easy to work with, microscope-wise, since they are very tough and not easily softened up for sectioning and slide preparation. Fortunately, since spore morphology is pretty much the only thing you're interested in (from an identification standpoint, anyway), you will not need to worry about keeping other microscopic structures intact. I slice a small sliver from the surface of a Xylaria, making sure that I have sliced just deeply enough to sever some perithecia (illustration), which are embedded between the surface and the tough, white flesh. Then I soak it in 90% alcohol as I would any section, before soaking it in water—for much longer than usual. When it has softened up as much as I think it is going to, I put in on the slide and begin slicing the &@%$ out of it with the razor blade, again and again, until I have very tiny, mountable fragments that are not so thick and hard that they lead to a cracked coverslip when I crush the mount. Xylaria spore morphology, including the thin, pale "germ slits" that can be crucial to identification, is best revealed in water mounts.

Species Pages:

Xylaria cornu-damae Xylaria cubensis Xylaria hypoxylon Xylaria liquidambar Xylaria longiana Xylaria longipes Xylaria magnoliae Xylaria polymorpha

Asexual stage of Xylaria cornu-damae

Cross-section: perithecia of Xylaria longiana

Spores with spiraling germ slits

References

Becerril-Navarrete, A.M., V.M. Gómez-Reyes, E. N. P. Villa & R. Medel-Ortiz (2018). Nuevos registros de Xylaria (Xylariaceae) para el estado de Michoacán, Mexico. Scientia Fungorum 48: 61–75.

Callan, B. E. & J. D. Rogers. (1993). A synoptic key to Xylaria species from continental United States and Canada based on cultural and anamorphic features. Mycotaxon 46: 141–154.

Fournier, J., F. Flessa, D. Peršoh & M. Stadler (2010). Three new Xylaria species from southwestern Europe. Mycological Progress 10: 33–52.

Fournier, J. (2014). Update on European species of Xylaria. Retrieved 1 September, 2020 from the ASCOFrance website: http://www.ascofrance.fr/uploads/xylaria/201406.pdf

Ju, Y. -M., J. D. Rogers & H. -M. Hsieh (2018). Xylaria species associated with fallen fruits and seeds. Mycologia 110: 726–749.

Laessoe, T. & Lodge, D. J. (1994). Three host-specific Xylaria species. Mycologia 86: 436–446.

Medel, R., R. Castillo & G. Guzmán (2008). Las especies de Xylaria (Ascomycota, Xylariaceae) conocidas de Vercruz, México y discusión de nuevos registros. Revista Mexicana de Micología 28: 101–118.

Medel, R., G. Guzmán & R. Castillo (2010). Adiciones al conocimiento de Xylaria (Ascomycota, Xylariales) en México. Revista Mexicana de Micología 31: 9–18.

Peršoh, D., M. Melcher, K. Graff, J. Fournier, M. Stadler & G. Rambold (2009). Molecular and morphological evidence for the delimitation of Xylaria hypoxylon. Mycologia 101: 256–268.

Rogers, J. D. (1979). Xylaria magnoliae sp. nov. and comments on several other fruit-inhabiting species. Canadian Journal of Botany 57: 941–945.

Rogers, J. D. (1983). Xylaria bulbosa, Xylaria curta, and Xylaria longipes in continental United States. Mycologia 75: 457–467.

Rogers, J. D. (1984). Xylaria acuta, Xylaria cornu-damae, and Xylaria mali in continental United States. Mycologia 76: 23–33.

Rogers, J. D. (1984). Xylaria cubensis and its anamorph Xylocoremium flabelliforme, Xylaria allantoidea, and Xylaria poitei in continental United States. Mycologia 76: 912–923.

Rogers, J. D. (1986). Provisional keys to Xylaria species in continental United States. Mycotaxon 26: 85–97.

Rogers, J. D. & B. E. Callan (1986). Xylaria polymorpha and its allies in continental United States. Mycologia 78: 391–400.

Rogers, J. D., F. San Martin & Y. -M. Ju (2002). A reassessment of the Xylaria on Liquidambar fruits and two new taxa on Magnolia fruits. Sydowia 54: 91–97.

Rogers, J. D., A.N. Miller & L. N. Vasilyeva (2008). Pyrenomycetes of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. VI. Kretzchmaria, Nemania, Rosellinia and Xylaria (Xylariaceae). Fungal Diversity 29: 107–116.

San Martin, F., P. Lavin & J. D. Rogers. (2001). Some species of Xylaria (Hymenoascomycetes, Xylariaceae) associated with oaks in Mexico. Mycotaxon 79: 337–360.

Stadler, M., D. L. Hawksworth & J. Fournier (2014). The application of the name Xylaria hypoxylon, based on Clavaria hypoxylon of Linnaeus. IMA Fungus 5: 57–66.

This site contains no information about the edibility or toxicity of mushrooms.

Cite this page as:

Kuo, M. (2020, July). The genus Xylaria. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/xylaria.html

© MushroomExpert.Com