amherst (original) (raw)

UMILTA WEBSITE, JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND ITS CONTEXTS �1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY || JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF LOVE || HER TEXTS ||HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN || BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT PORTAL Copyright of the Amherst Manuscript images belong to the British Library, further reproduction being prohibited.

THE JULIAN OF NORWICH

BRITISH LIBRARY AMHERST MANUSCRIPT

(ADDITIONAL 37,790) PROJECT

Dearworthy Reader,

ILLIAM Langland in Piers Plowman wrote movingly about monasteries and schools of learning as not being places of polemic. He was looking back rather to Benedictinism's contemplative, book-producing-and-reading, monasteries, rather than towards the seething universities of his day, where Benedictines, Cistercians, Carmelites, Augustinians, Dominicans, and Franciscans, could unite in condemning a woman, Marguerite Porete , to burning at the stake, when not brawling against each other. Yet, in reaction perhaps to that holocaust, Dominican men and women, the Friends of God, came to collaborate, across the face of Europe, in the writing of contemplative texts, texts that will later be treasured, Julian's among them, by exiled English Brigittine and Benedictine nuns on the Continent. While in England those texts follow in the footsteps of Richard Rolle writing for Margaret Kirkeby and were to be treasured in Carmelite and Carthusian settings where men were encouraging women's contemplative lives of prayer. These are rich textual communities, shattered by the gender apartheid of the Universities, the Renaissance and the Reformation.

ILLIAM Langland in Piers Plowman wrote movingly about monasteries and schools of learning as not being places of polemic. He was looking back rather to Benedictinism's contemplative, book-producing-and-reading, monasteries, rather than towards the seething universities of his day, where Benedictines, Cistercians, Carmelites, Augustinians, Dominicans, and Franciscans, could unite in condemning a woman, Marguerite Porete , to burning at the stake, when not brawling against each other. Yet, in reaction perhaps to that holocaust, Dominican men and women, the Friends of God, came to collaborate, across the face of Europe, in the writing of contemplative texts, texts that will later be treasured, Julian's among them, by exiled English Brigittine and Benedictine nuns on the Continent. While in England those texts follow in the footsteps of Richard Rolle writing for Margaret Kirkeby and were to be treasured in Carmelite and Carthusian settings where men were encouraging women's contemplative lives of prayer. These are rich textual communities, shattered by the gender apartheid of the Universities, the Renaissance and the Reformation.

In the essay that follows, take the scholarly words as the least important of all, centring instead on the scraps and fragments of Julian's theology in Julian's words, that are present especially in manuscript form in this essay. So wrote a contemplative and anonymous monk as preface to our forthcoming edition of all the extant Julian manuscripts. And we warmly invite your participation in this Godfriends' project, as contemplative, as scholar, as general reader.

Transcriptions from the British Library Amherst Manuscript given on this Umilta Website are of Thomas de Froidmont, Golden Epistle , written for Margaret of Jerusalem (these ascriptions are uncertain), Henry Suso, Horologium Sapientiae , Jan van Ruusbroec, Sparkling Stone , Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love . Also included in the manuscript are Richard Rolle and Richard Misyn writing for women anchoresses named 'Margaret' (for a modern transcription see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/rolle/fire.html�), as well as Marguerite Porete, Mirror of Simple Souls . Archbishop Arundel, Constitution , may give its context. Likewise the Letter of Cardinal Adam Easton to the Abbess of Vadstena and Birgitta of Sweden/Alfonso of Jaen, Revelationes XIII/Epistola solitarii ad reges . While Margery Kempe 's conversation with Julian of Norwich may have occurred about this date. To hear it, listen to <soulcity.mp3>

**{

**e earliest surving Julian of Norwich manuscript may contain the latest version of her Showing of Love. It is the Short Text version, giving the date of its writing '1413', in its 97th folio, third and fourth lines as: 'Anno d_omi_ni mill_esi_mo.CCCC/xiij'. It was purchased at the Lord Amherst Sale in 1910, becoming British Library Additional 37,790.

**e earliest surving Julian of Norwich manuscript may contain the latest version of her Showing of Love. It is the Short Text version, giving the date of its writing '1413', in its 97th folio, third and fourth lines as: 'Anno d_omi_ni mill_esi_mo.CCCC/xiij'. It was purchased at the Lord Amherst Sale in 1910, becoming British Library Additional 37,790.

{

ere es Avisioun Schewed Be the goodenes of god to Ade=/uoute woman_n._ and hir Name es Julyan that is recluse atte/ Norwyche and 3itt. ys ou n lyfe. Anno d_omi_ni mill_esi_mo CCCC/xiijo. In the whilk visyou_n_ Er fulle many Comfortabylle wordes and/ gretly Styrrande to alle thaye that desyres to be crystes loovers.

ere es Avisioun Schewed Be the goodenes of god to Ade=/uoute woman_n._ and hir Name es Julyan that is recluse atte/ Norwyche and 3itt. ys ou n lyfe. Anno d_omi_ni mill_esi_mo CCCC/xiijo. In the whilk visyou_n_ Er fulle many Comfortabylle wordes and/ gretly Styrrande to alle thaye that desyres to be crystes loovers.

{  Desyrede thre graces be the gyfte of god The ffyrst was/ to have mynde of Cryste es Passioun. The Secou_n_de was/ bodelye syekenes And the thryd was to haue of goddys gyfte thre wo=/undys. ffor the fyrste come to my mynde with devocou_n_ me thought/ I hadde grete felynge in the passyou n of cryste Botte 3itte I desyrede/ to haue mare be the grace of god. me thought I wolde haue bene

Desyrede thre graces be the gyfte of god The ffyrst was/ to have mynde of Cryste es Passioun. The Secou_n_de was/ bodelye syekenes And the thryd was to haue of goddys gyfte thre wo=/undys. ffor the fyrste come to my mynde with devocou_n_ me thought/ I hadde grete felynge in the passyou n of cryste Botte 3itte I desyrede/ to haue mare be the grace of god. me thought I wolde haue bene

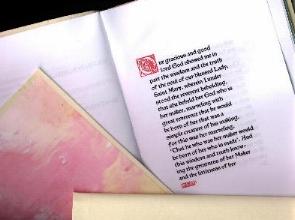

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 97. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

This first folio is tantalizingly marred by a repair, a strip of paper pasted to its edge taking the place of now lost annotations. They were likely made by the Carthusian James Grenehalgh, to be discussed later in this essay.

THE MANUSCRIPT'S SCRIBE

The whole manuscript is a florilegium assembled by one scribe whose dialect is of Grantham, Lincolnshire,

|| Laing, Margaret. 'Linguistic Profiles and Textual Criticism: The Translations by Richard Misyn of Rolle's Incendium Amoris and Emendatio Vitae '. Middle English Dialectology: Essays on Some Principles and Problems . Ed. Margaret Laing. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1989. Pp. 188-223. || perhaps the Lincoln/York Carmelite Richard Misyn writing, as the manuscript states, circa 1435, for the anchoress Margaret Heslyngton. We know that the anchoress Emma Stapleton (whose father, Sir Miles Stapleton, fought, like Chaucer's Knight, at Alexandria, and who, as the executor of Isabelle, Countess of Suffolk, would have known Julian of Norwich), had for her spiritual director the Carmelite Adam Hemlyngton, D.D., when she was enclosed at the Norwich Carmelite Friary, 1421-1443, and that another woman member of her family, Agnes Stapleton, owned and willed a similar contemplative text, Chastising of God's Children .

Miles Stapleton's Book of Hours inclusion of the Passion told from the four Gospels in Latin by an Augustinian Hermit seems influenced by Julian's vision:

aaa

[For more information on the Carmelites Richard Misyn and Adam Hemlyngton and the recluses Margaret Heslyngton and Emma Stapleton, see the Oxford M.Phil thesis by Johan Bergstrom-Allen online at http://www.carmelite.org/jnbba/thesis.htm�]

This same Amherst scribe, according to A.I. Doyle, also writes out Mechtild von Hackeborn, Book of Gostlye Grace, British Library, Egerton 2006 (owned by King Richard III and his wife, Anne Warwick) and a Middle English translation of Deguileville, St John's College, Cambridge, G.21.

|| Mechtild of Hackeborn. The 'Book of Gostlye Grace'. Ed. Theresa A. Halligan. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1979. Studies and Texts 46.|| The following texts in this florilegium are earlier or contemporary with Julian, though the initial gatherings with the Richard Rolle translations by Richard Misyn are later than Julian. The first texts, with Richard Misyn translating Richard Rolle, A.I. Doyle concurs, could have have been added last. It is just within the realm of possibility that this gathering was indeed written in '1413', when Julian is still alive, at seventy years of age. Its language so emphatically states that fact, and the entire text is written as if to present Julian's voice to us as one that is a living witness to the event she describes, its form even like that of a legal document prepared for a canonization process that is looked for following her decease. Indeed we have such texts preserved now at Uppsala and Oxford, created within the Brigittine circle in Norwich, Lincoln, York and Vadstena before and for the founding of Syon Abbey, concerning the canonizations of Birgitta, Catherine, her daughter, Petrus Olavi, Archbishop of York, Richard Scrope, and Richard Rolle. Likewise, Birgitta of Sweden had continued writing versions of her Showing, her Revelationes, from the age of forty through her seventieth year. Then around this text are gathered others, Richard Rolle's and Birgitta of Sweden's among them, all of use for living the contemplative life of prayer, most translated into English, meaning the intended audience, the reader of this manuscript, is likely an intelligent woman, unable to be educated at school and university. Imagine her as an Emma Stapleton, or a Margaret Heslyngton, under the spiritual direction of Carmelites such as Adam Hemlyngton or Richard Misyn. Someone who had perhaps known Julian of Norwich and who sought to share in her contemplative library.

Elsewhere, A.I. Doyle cautions against scholars, such as Hope Emily Allen, Margaret Deanesly and Michael Sargent, seeing the propagation of Richard Rolle manuscripts as largely a Carthusian monopoly, mentioning in particular a Richard Rolle, Short Text Incendium manuscript, Lincoln Cathedral 218, as decorated with pictures of Carmelite friars, not Carthusians.

|| A.I. Doyle. 'Carthusian Participation in the Movement of Works of Richard Rolle Between England and Other Parts of Europe in the 14th and 15th Centuries'. Kart�usermystic und -Mystiker: Dritter Internationaler Kongress �ber die Kart�usegeschichte und Spiritualitat. Analecta Cartusiana, 55. Ed. James Hogg. Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 1981. Band 2. Pp. 109-120, esp. 111. ||

THE SHOWING OF LOVE'S CORRECTOR

There are interesting corrections made to the Amherst Julian of Norwich Showingof Love text but not elsewhere in Amherst in a hand that reminds one of the Norwich Castle Manuscript . Given that the Showing of Love text itself stresses that it is being written in '1413' during Julian's lifetime, it is just within the realm of possibility that we have her here correcting her scribe, completing his lacunae, his eye-skips. This hand also seems to match that of the rubricator to this part of the manuscript.

Fol. 101v. +_ther_fore it semed to me that synne is nou3t. ffor in all e thys synne

Fol. 106v . T+ lyke in this i was inparty fyllyd w_ith_ compassiou_n_

Fol. 107 . + & it langes to th_e ryall_e lordeschyp of god for to haue his p_ri_ve consayles

Fol. 108v . +what may make me mar_e_ to luff myne evenc_ri_sten

In each instance these corrections give concepts integral to Julian's thought, to her theology.

THE NORWICH CASTLE MANUSCRIPT

As with the Westminster Cathedral and British Library Amherst Manuscripts the Norwich Castle Manuscript (Norwich Castle 158.926/4g.5), is a florilegium of contemplative and catechetical texts. It is said to contain 'Theological Treatises', specifically 'An Epistle of St Jerome to the Maid Demetriade who had vowed Chastity', a 'Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins', a 'Treatise on the Pater Noster', and 'Pore Caitif'. Richard Copsey, O.Carm. notes that the 'Treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins' is written by Richard Lavenham, O.Carm., who lectured on Birgitta's Revelationes at Oxford and who was Richard II's confessor. The work is dated by paleographers as written in the beginning of the 15th century. Its dialect is of the Norwich region. This gives us a manuscript produced during Julian's lifetime, in the region where she was enclosed and, like Amherst, with both Carmelite and Brigittine associations. It begins with a letter written, it says by Saint Jerome (though actually by Pelagius) to the maid Demetriade who had vowed virginity. Its other texts are of interest for catechetical purposes, the Pore Caitif, the 'Treatise on the Lord's Prayer'. Much of its wording directly reflects that in Julian's Long Text Showing of Love .

It begins with a lovely Gothic letter { in gold leaf upon a purple ground:

in gold leaf upon a purple ground:

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 1

It also has another letter { given in a less florid decorative manner at folio 31:

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 31.

It seems worthwhile to compare these capitals with those in Amherst:

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol 97. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

The scribes of the two manuscripts are clearly not the same but their layout is similar, as if the writer of the Norwich Castle Manuscript had had the employment of the scribe of the Amherst Manuscript, perhaps for the production of a book for one Emma Stapleton who would later become an enclosed anchoress with the Carmelites in Norwich. Both manuscript texts begin, not with thorn, but with TH. Another most beautiful manuscript Julian likely saw, owned by Adam Easton, O.S.B., of Norwich, has a similarly beautiful Gothic { for Trinitas, in gold leaf with green intertwines, beginning its invocation to Wisdom, the Prayer of St Dionysius, in its fine thirteenth-century Victorine manuscript, now at Cambridge University Library. Amusingly, Amherst's {

for Trinitas, in gold leaf with green intertwines, beginning its invocation to Wisdom, the Prayer of St Dionysius, in its fine thirteenth-century Victorine manuscript, now at Cambridge University Library. Amusingly, Amherst's { , with the smaller

, with the smaller  nestling within, is unwittingly replicated on the present gate to THE BRITISH LIBRARY at St Pancras. Perhaps nothing but coincidences, but nevertheless Italians would call these, 'elegant combinations'.

nestling within, is unwittingly replicated on the present gate to THE BRITISH LIBRARY at St Pancras. Perhaps nothing but coincidences, but nevertheless Italians would call these, 'elegant combinations'.

If we compare the hand of the corrector to the Amherst Showing of Love to that of the scribe of the Norwich Castle Manuscript we see some similarities. They share a squarishness. (Likewise the hand of Cardinal Adam Easton of Norwich, who predeceased Julian, has a squarish, Tudor-seeming, quality to it. The Amherst corrector and the Norwich scribe share similar m's, n's, l's, k's, d's, a's, e's, &'s and yochs. However the Norwich Castle Manuscript is written in a deliberate bookhand with differently formed thorns, w's, s's and y's to those of Amherst's corrector, the h's and ff's having different descenders.

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 101v. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

Norwich Castle Manuscript, fol. 31.

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 108. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

Likely in neither the corrector to Amherst nor in the Norwich Castle Manuscript do we see Julian's actual hand. Nevetheless it is possible that Dame Emma Stapleton could have corrected Dame Julian's text, having another at hand from which to supply lacunae. Or that these corrections are made later at Syon Abbey where the largest secure collection of Julian's Showing of Love manuscripts came to hand, in the Sisters' library there (it is not listed in the surviving Catalogue for the Brothers' Library), until the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

THE AMHERST FLORILEGIUM'S CONTENTS

The Amherst Manuscript florilegium is intended for a Latin-less woman contemplative, likely of the generation following Julian's. The manuscript may include translated texts originally in Julian's own contemplative library, then recycled by copying it out for a later anchoress. One can envision Julian herself leaving instructions as to what it should contain. This entire manuscript, and another by this scribe, are worthy of study in the collaborative spiritual direction of women anchoresses, and of their own production of theological texts, by Marguerite Porete, Julian of Norwich, Birgitta of Sweden, Mechtild of Hackeborn. With the inclusion of the works by Porete, Suso and Ruusbroec this collection is also related to the Dominican movement on the continent, known as theFriends of God , where Porete was influenced by Pseudo-Dionysius and William of St Thierry, her clandestine work influencing in turn Meister Eckhart and his disciples such as John Tauler and Henry Suso, a movement characterized by deep respect for women and indeed collaboration with them in the creation of contemplative theological texts. This movement, in turn, through Magister Mathias, who associated with the Dominicans in Paris and Stockholm, strongly influenced Birgitta of Sweden.

Among the texts now transcribed from the Amherst Manuscript on this Website are those of Froidmont , Ruusbroec , Suso , but not Porete :

Bernard of Clairvaux [Thomas de Froidmont]The Golden Epistle, Written for His Sister Margaret of Jerusalem (A95v-96v). [Other related texts are the Life of Christina of Markyate and the Flemish account of the Life of Jan van Beverley, John of Beverley, whom Julian mentions in her Long Text.]

|| For which see also: Margaret of Jerusalem/Beverley by Thomas of Beverley/Froidmont , Her Brother, Her Biographer and Saint Birgitta of Sweden: Her Relics .|| 'Elegie de Thomas de Froidmont'. Biblioth�que des Croisades. Ed. Joseph F. Michaud. Paris: Ducollet, 1829. III.569-575.|| Citing Annales de Citeux. Ed. Manrique. III: for the year 1174, Chapter 3; 1187, Chapter 8; 1189, Chapter 5; 1192, Chapter 3. || Aron Andersson and Anne Marie Franz�n, Birgittareliker. Stockholm: Alqvist & Wiksells, 1975.|| I lack access to: Paul Gerhardt Schmidt, "Peregrinatio periculosa: Thomas von Froidmont �ber die Jerusalem-Fahrten seiner Schwester Margareta," Kontinuit�t und Wandel: Lateinische Poesie von Naevius bis Baudelaire, Franco Munaro zum 65. Geburtstag (Hildesheim: Weidmann, 1986), 461-85.|| William Paden, "De Monachis rithmos facientibus: H�linant de Froidmont, Bertran de Born, and the Cistercian General Chapter of 1199," Speculum 55 (1980): 669-85.|| Colledge Edmund. 'Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century English Versions of 'The Golden Epistle of St Bernard'. Mediaeval Studies 37 (1975), 122-129. || Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love (A97-115)

Jan van Ruusbroec Sparkling Stone Complete (A115-130)

|| Ruysbroeck, Jan. The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage, The Sparkling Stone, The Book of Supreme Truth. Trans. C.A. Wynschenk Dom, from the Flemish. Introd. and Notes, Evelyn Underhill. London: Dent, 1916. || _______.The Book of the Twelve Beguines . Trans. John Francis [Evelyn Underhill], from the Flemish. London: John M. Watkins, 1913. || ________. Flowers of a Mystic Garden. Trans. C.E.S. from the French of Ernest Hello. London: John M. Watkins, 1912. || ________. The Kingdom of the Lovers of God. Trans. T. Arnold Hyde, from the Latin of Laurence Surius. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1919. || _______. Reflections from the Mirror of a Mystic. Trans. Earle Baillie, from the French of Ernest Hello. London: Thomas Baker, 1905. || Ruusbroec, Jan van. The Spiritual Espousals and Other Works. Trans. James A. Wiseman, Preface, Louis Dupr�. New York: Paulist Press, 1985.|| ________. Vanden Blinckenden Steen. Ed. Lod Moereels, L. Reypens. Tielt en Bussum: Lannoo, 1981.|| Colledge, Eric. 'The Treatise of Perfection of the Sons of God: A Fifteenth-Century English Ruysbroek Translation'. English Studies 33 (1952), 49-66. || Joyce Bazire and Eric Colledge. The Chastising of God's Children and the Treatise of the Perfection of the Sons of God (Oxford: Blackwell, 1957).|| Henry Suso Horologium Sapientiae Excerpt (A135v-136v) || Suso, Henry.The Life of Blessed Henry Suso by Himself. Trans. Thomas Francis Knox. London: Methuen, 1913 || The Exemplar: With Two German Sermons. Trans. and ed., Frank Tobin. Preface, Bernard McGinn. New York: Paulist Press, 1989. || Ancelet-Hustache, Jeanne. Master Eckhart and the Rhineland Mystics. London: Longmans, 1957. [Gives Suso's manuscript illuminations.] || Marguerite Porete Mirror of Simple Souls Complete (A137-225) || [Porete, Margaret.] The Mirror of Simple Souls. Ed. Clare Kirchberger. London: Burns Oates and Washbourne, 1927 [Edits Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 505, where text occurs with Chastising of God's Children.] ||Margaretae Porete Speculum simplicium animarum/ Marguerite Porete, Le mirouer des simples ames. Ed. Paul Verdeyen and Romana Guarnieri. Turnhout: Brepols, 1986. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Medievalis, 69 || Le mirouer des simples ames. Ed. Romana Guarnieri. Archivio Italiano per la storia de la Piet� 4 (Rome, 1965). || Mirror of Simple Souls. Ed. Marilyn Doiron. Archivio Italiano per la storia de la Piet� 5 (Rome, 1968), 241-355. [Edits Cambridge, St John's College 71 (C21)] ||The Mirror of Simple Souls. Trans. Ellen L. Babinsky, Preface, Robert E. Lerner. New York: Paulist Press, 1993. || Watson, Nicholas. 'Melting into God the English Way: Deification in the Middle English Version of Marguerite Porete's Mirouer des simples ames enienties '. Prophets Abroad: The Reception of Continental Holy Women in Late-Medieval England. Ed. Rosalynn Voaden. Cambridge: Brewer, 1997. Pp. 19-49. || The Amherst Manuscript's Marguerite Porete, Mirror of Simple Souls, lacks an edition. This will be of the greatest importance and usefulness to Julian studies. Julian has verbal echoes to Marguerite in all versions of her Showing of Love and appears to know the fate of its author, burnt at the stake in Paris in 1310, condemned by the Doctors of Theology of the Sorbonne.

Brief excerpts from St Birgitta of Sweden

An amateurish drawing on the final folio of a mother and child where the mother is cross-nimbed, the cross made from three great nails, but not the child. The Short Text omits Julian's discussion of 'Jesus as Mother'. Yet this drawing appears to know of that theological argument and to portray it. This knowing is possible if the manuscript came to rest in a communal setting with access to the other versions of Julian's text. The manuscript drawing is especially intriguing in a Brigittine context where the Sisters wear white crowns with crosses, five red roundels at the interstices upon their black veils, in memory - and contemplative knowing - of the Five Wounds of Christ.

Courtesy, Juliana Dresvina

Courtesy, Juliana Dresvina

In relation to these see also John Whiterig, Contemplating the Crucifixion , Durham Manuscript B.IV.34.

THE '1413' SHORT TEXT'S CONTEXTS

I. EUROPE

Julian is writing her Short Text in a context that is both Continental and Insular, both European and English. If she is having it written in 1413, her likely former patron, certainly a 'Aman . . . of halye kyrke ', Cardinal Adam Easton of England, Benedictine of Norwich, is dead. His titular basilica in Rome was Santa Cecilia in Trastevere.

The Short Text manuscript of Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love stresses St Cecilia by engrossing that name at fol. 97v, and the text makes use of St Cecilia's three neck wounds,

I harde Aman telle of halye kyrke of the Storye of.Saynte Ce =

I harde Aman telle of halye kyrke of the Storye of.Saynte Ce =

cylle . In the whilke schewynge. I vndyrstode that sche hadde thre

woundys with ASwerde. In the nekke withe the whilke sche py=

nede to the dede. By the styrrynge of this. I conseyvede amyghty

desyre Prayande oure lorde god that he wolde grawnte me thre

woundys in my lyfe tyme that es to saye the woundys of contricyoun

the wounde of compassyoun & the wounde of wylfulle langgynge to god,

as its threefold ordering principle, much in the same manner as had St Catherine of Siena ordered her 1378 Dialogo or 'Revelation of Divine Love' according to a fourfold division, based on four petitions. It is just possible that this same Cardinal Adam Easton, who was in Norwich writing the Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae and of her Revelationes, effecting her canonization at exactly the same time that Julian was writing her Long Text of the Showing of Love , had been Julian's spiritual director bringing to her from the Continent contemplative works such as Marguerite Porete, Henry Suso, Jan van Ruusbroec and Catherine of Siena. His biography notes that he wrote many contemplative and vernacular treatises on the Spiritual Life of Perfection. I suspect that the exemplar manuscript to that which came to be owned by Syon Abbey and from which Wynken de Worde printed the_Orcherd of Syon_ was given Julian by Adam.

Transcription: ||P Here begynneth the boke of dyuyne doctryne. That is to/ saye of goddes techyng. Gyuen by the person of god the fa/der to the intelleccyoun of the gloryous vyrgyne seynt Kathe-/ryn of Seene/ of the ordre of seynt Domynycke. Which was/ wryte n as she endyted i_n_ her moder tongue. Wha_n_ she was in co_n/te_m_placyon & rapt of spyryte she herynge actualy. And i_n the same/ tyme she tolde before many what our lorde god spake i_n_ her.

And here foloweth the fyrst/ chapytre of this boke. Which/ is how the soule of this mayde/ was oned to god & how then she/ made .iiii. petycyons to oure/ lorde in that tyme of contem/placyon and of the answere/ of god and of moche other do/ctryne: as it is specyfyed in the/ kalender before. Capt.1.

**{A}**soule that is reysed up/ with heuenly and/ ghostly desyers & af-/feccyo_n_s to the worshyp/ 00Oof god & to the helthe/ of mannes soules with a greate . . .

________

The Orcherd of Syon (Westminster: Wynken de Worde, 1519), Catherine of Siena's Dialogo in Middle English, states in its colophon that: ' a ryghte worshypfull and deuoute gentylman mayster Rycharde Sutton esquyer stewarde of the holy monastery of Syon fyndynge this ghostely tresure these dyologes and reuelacions . . . of seynt Katheryne of Sene in a corner by itselfe wyllynge of his greate charyte it sholde come to lyghte that many relygyous and deuoute soules myght be releued and haue comforte therby he hathe caused at his greate coste this booke to be prynted'.

|| The Orcherd of Syon (London: Wynken de Worde, 1519); The Orcherd of Syon, ed. Phyllis Hodgson and Gabriel M. Liegey (London: Oxford University Press, 1966), EETS 258.18:11.||

The Short Text of Julian's Showing of Love is closer to Catherine's Dialogo than are the other W and P versions of her text. It is even just possible that Julian, through first William Flete, then Adam Easton, influenced Catherine of Siena, then that Easton gave Julian Catherine's resulting Dialogo. William Flete's Remedies Against Temptations is quoted in the Westminster Text passim, Flete then becoming Catherine's disciple and executor, and Catherine's 1378 Dialogo opening, of the knowing of oneself and God, is present in the Westminster Text. Who influenced whom? || See Phyllis Hodgson, 'The Orcherd of Syon and the English Mystical Tradition', Proceedings of the British Academy 50 (1964), 229-249, for discussion of textual relations between Catherine of Siena's Dialogo , Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love; William Flete, 'Remedies against Temptations: The Third English Version of William Flete', ed. Eric Colledge and Noel Chadwick, _Archivio Italiano per la Storia della Pieta_` 5 (Rome, 1968). || Cardinal Adam Easton had worked with Catherine of Siena and Alfonso of Ja�n, 1379, defending Urban VI's election. Cardinal Adam Easton had returned to his titular church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere by 1396, Archbishop Arundel being touched by Cardinal Adam Easton's kindness to him in Rome in that year; and by 1397 Norwich's Adam Easton was buried in that Roman basilica in a tomb opposite St Cecilia's.

Related to the three wounds of Cecilia are also the five wounds of Christ. Several English manuscripts speak of a solitary and recluse woman who sought to know Christ's wounds: Oxford, Bodleian Library, Lyell 30, XV Os of St Birgitta, ' A woman solitari and recluse covetyng to knowe cristis woundus '; British Library, Add. 37,787, fols. 71v-74, ' Femina quedam solitaria et reclusa vulnerum xristi scire cupiens ', waiting thirty years to do so, 'Sciendum est ante quod signis in peccatis esset triginta annis '; Harley 172, fol. 3, on Orysons on wounds shown to a solitary and recluse woman, 'She covetynne to knowe the nombre of the wondys of oure lord Jhesu cryst oftyne tymes she prayede God of his specyal grace that he wolde vouchsafe to shewe hym to hire '; Harley 494, fols. 61-62, echoes Amherst's ' Ade=uoute womann, and hir Name es Julyan that is recluse atte Norwyche ', and crystallizes all the above when speaking of ' Certaine prayers shewyd unto a devote person called mary Oestrewyk '. For Julian of Norwich lived near Westwick Street and Gate in Norwich and Adam Easton wrote his name 'OESTONE'.

|| 'LIBER:DNI/ADE:OESTONE:/MONACHI:NOR/WICENSIS', Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 180, Norwich Cathedral Priory shelf mark X,xlvi. || Norwich's Jewry lay between Westwick and Conisford, clustered for safety about Norwich Castle, and in the twelfth century was the second largest in England after London, though declined in the thirteenth century. Both Julian and Adam demonstrate a knowledge of Hebrew, Adam owning manuscripts, such as Rabbi David Kimhi, in Hebrew. Both use the contemplative mysticism of Pseudo-Dionsysius, a text Adam Easton owned in an exceedingly fine thirteenth-century Victorine manuscript. || Michael Camille. The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989. Pp. 182-185, Fig. 101. Giving graffiti on tallage roll in the London Public Record Office satirizing Norwich's Jewry. This Jewry provided the funds for building Norwich Cathedral.|| It is possible that Julian's real name is 'Mary Easterweek', 'Westwick', 'Weston', or 'Easton', 'wick' meaning 'town'. This frame, 'of a woman solitary and recluse covetous to know Christ's wounds', is sometimes given to the English _XV O_s, falsly attributed to St Birgitta. Usually these _XV O_s and these 'woman solitary and recluse' incipits, like Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love, occur in devotional manuscripts associated with Syon Abbey. || Nicholas Rogers, 'About the 15 "O"'s, the Brigittines and Syon Abbey',St Ansgar's Bulletin 80 (1984), 29-30. || Of interest, too, is that Margery Kempe's amanuensis first rejects her, then comes to accept her, through reading in Cardinal Jacques Vitry's book of Marie d'Oignies' ' wondirful compassyon that sche had in his Passyon thynkyng '. Similarly had Birgitta's director, Magister Mathias, doubted her, then noted the likeness to Marie d'Oignies and to Cardinal Jacques de Vitry's important support of her. || Book of Margery Kempe EETS 212.152-153. || Where the Westminster Text, W89, and the Long Text, P73, give Julian being shown ' for prayer', in the Amherst Short Text, this becomes 'foure prayers', 'Four Prayers ' (A109.32). This may be a reference to St Birgitta's Quattuor Orationes , her 'Four Orysons', her 'Four Prayers', sometimes associated with Birgitta's 1368 Vision of the Crucifix at St Paul's Outside the Walls in Rome, and which in turn are sometimes confused with XV O s. Cardinal Adam Easton's Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae (likely written in Norwich, according to the bills paid for shipping his books there at that date in the Norwich Record Office discovered by Joan Greatrex), supported Birgitta's canonization in the attack against her by a Perugian theologian, her cause's 'Devil's Advocate', who objected to the rudeness of her writing, to the Rule written by a woman, and specifically to these Four Prayers, two of which are addressed to the bodies of Christ and Mary. || Birgitta of Sweden, Revelationes XII; Chastising of God's Children , p. 224, fol. 89v || Julian, or her Amherst scribe, appear to remember that controversy that swirled about Birgitta of Sweden and for which Birgitta had been ably defended by Cardinal Adam Easton of Norwich. || Bodleian Library, Hamilton 7, fols. 231-239. || Julian's Showing of Love, Birgitta's Quattuor Orationes and the English XV O s seem formed in a matrix, appearing to allude to each other. The matrix is largely Brigittine.

New material in this version of the Showing of Love, added to its ending, and not in the Westminster or Paris texts, is from Alfonso of Ja�n, Epistola Solitarii ad reges (1373), discussing the Discernment of Spirits and written in defense of Birgitta of Sweden's visionary Revelationes ,

||Eric Colledge, 'Epistola solitarii ad reges: Alphonse of Pecha as Organizer of Brigittine and Urbanist Propaganda', Mediaeval Studies 18 (1956), 19-49; Arne J�sson, Alfonso of Ja�n: His Life and Works with Critical Editions of the 'Epistola Solitarii', the 'Informaciones' and the 'Epistola Serui Christi' (Lund: Lund University Press, 1989); Hans Torben Gilkaer, The Political Ideas of St Birgitta and her Spanish Confessor, Alfonso Pecha: Liber Celestis Imperatoris ad Reges: A Mirror of Princes (Odense: Odense Universitet, 1993).|| and which was also used in Adam Easton's Defensorium Sanctae Birgittae (1391), || James Hogg, 'Cardinal Easton's Letter to the Abbess and Community of Vadstena', Studies in St Birgitta and the Brigittine Order , ed. James Hogg (Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universitat Salzburg, 1993), II.20-26. || in the Cloud Author's Epistles and Treatises (of unknown date and authorship), but which, like Cardinal Adam Easton's Latin writings, are deeply influenced by Pseudo-Dionysius and the Victorines, || Cloud Author, 'A Pistle of Discrecioun of Stirings', 'A Tretis of Discrecyon of Spirites', in Deonise Hid Diuinite, ed. Phyllis Hodgson (London: Oxford University Press, 1958), EETS 231.61-93. || in the anonymous Chastising of God's Children, Chapters XIX-XX (written between 1382-1408), and in Dame Julian's conversations with Margery Kempe, circa 1413, when this manuscript may have been being written for Julian. || Hope Emily Allen, The Book of Margery Kempe, EETS 212.lviii, who also notes that much of The Chastising of God's Children comes from a sermon by John Tauler, p. liv; Bazire and Colledge note, p. 35, that the English translation interpolates to Ruusbroec's text, ' neither to pope' 'ne to cardinal' an observation not in the original, giving rise to the thought that this could be one of Adam Easton's lost translations into the vernacular of spiritual texts and that he is jokingly alluding to himself. The text circulated to Brigittine, Cistercian and Benedictine abbeys for women by means of the Charterhouses at Sheen and London. Bazire and Colledge also note that both the Cloud Author and the Chastising Author speak of heretics as the ' devil's contemplatives', p. 46. || The Epistola Solitarii exists in English translation in a fifteenth-century Norfolk manuscript of Birgitta's Revelationes, British Library, Cotton Julius F II, which uses 'Brigid ', from the Italian form of her name 'Brigida ', rather than 'Birgitt ', derived from the Swedish form, 'Birgitta '. || Rosalynn Voaden, God's Words, Women's Voices: The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late-Medieval Women Visionaries (York: York Medieval Press, 1999), pp. 159-181; 'The Middle English Epistola solitarii ad reges of Alfonso of Ja�n: An Edition of the Text in British Library MS Cotton Julius F ii', Studies in St. Birgitta and the Brigittine Order, ed. James Hogg (Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 1993), I.144. Cardinal Adam Easton's Latin copy of the Revelationes brought to Norwich would have been similar to those today in Palermo, Biblioteca Nazionale, IV.G.2, and New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M498, which were produced directly under the aegis and editorship of Bishop Hermit Alfonso of Ja�n for the purpose of the canonization procedure. Cotton Julius F II likely was produced in that Norwich setting of support for Birgitta.

The text is also to be found in Cambridge University Library, Ff.VI.33, fols. 38v-39, clustered with manuscripts which came there from Adam Easton's library at Norwich Cathedral Priory and from Syon Abbey.

Howe the spowse of cryst seynt Byrgitte hadde heuenly reuelations In the lordshype of the kyng of Norweye which ys northward last and uttyrineste of alle kynges so that be3onde the londys for men dwell yn. Ther was an holy lady Seynt Byrgytte. which whan she entended ynwardly to prayer. the bodye was pryuyd of alle strengthes and the soule in alle hir strengthes began to be most parfytly vygorous and stronge for to see. hyre. speke and fele gostly thynges. In so moche that she was ofte tyme rauysshed and herde many thynges spiritually tolde vnto hir in spyryt. or spirituall and intellectual vision� which thynges the same persone dredynge to be illudyd of that scorner the angell of derknes, undyr the lyknes of an angell of ly3t. aftirward wt grete reuerence and drede of god. mekely openyd and shewyd un to an archbysshope wyth other thre bysshopes and to a deuoute maystyr in diuinite. and to an abbot a ful deuoute and religiouse man. And they all and many other frendys of god heryng these thynges. and sadly and spiritual by comenyng togedyr therof preuyd that all these thynges were reuelyd to the same persone frome god. Of the good spirit of truth and of ly3t. and of special grace of the holy goost. We also find this text but in relation to Catherine of Siena, clustered in manuscript that come from Norfolk, of the Cloud Author's texts. And we also find these same words about an angel of darkness, seeming to be an angel of light at the Amherst's Showing of Love conclusion. It is the topic of conversation, again, that Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich share with each other in the Book. This is, as Rosalynn Voaden has shown, a burning issue during this period in connection with women's books of revelations.

II. ENGLAND

There was already anxiety, as well as support, on the Continent for women's visionary writing. It was to particularly be seen in the later condemnation by Jean Gerson, Chancellor of the University of Paris, of Marguerite Porete, Birgitta of Sweden and Jan van Ruusbroec. Though he was to amicably resolve his debate with Christine de Pizan, both agreeing to loathe the lecherous, sexist Roman de la Rose.

In England this anxiety and debate was further complicated by the political situation where John Wyclif's Lollardy was seen as instigating the Peasants' Revolt and the Oldcastle Uprising. Lollardy became punishable as both treason and heresy. Particularly singled out were lay persons, above all women, daring to teach theology, to write books and to translate the Bible into the vernacular. For the document promulgating and confirming censorship for the period 1401 through 1413 in England, see Archbishop Chancellor Arundel, Constitution, 1408.

|| Watson, Nicholas. 'Censorship and Cultural Change in Late-Medieval England: Vernacular Theology, the Oxford Translation Debate, and Arundel's Constitutions of 1409'. Speculum 70 (1995), 822-864 || _______. 'The Composition of Julian of Norwich's Revelation of Love'. Speculum 68 (1993), 637-683. || Margaret Aston. Lollards and Reformers: Images and Literacy in Late Medieval Religion. London: Hambledon Press, 1984.|| Anne Hudson. Lollards and Their Books. London: Hambledon Press, 1985.||Rita Copeland. 'Childhood, Pedagogy and the Literal Sense'. New Medieval Literatures. Ed. Wendy Scase, Rita Copeland and David Lawton. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997.|| Ralph Hanna. 'Some Norfolk Women and Their Books'. The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women. Ed. June Hall McCosh. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996.|| Claire Cross. '"Great Reasoners in Scripture": The Activity of Women Lollards 1380-1530'. Medieval Women. Ed. Derek Baker. Oxford: Blackwell, 1978. || An additional area of study in relation to the clampdown by Bishop Despenser of Norwich and Archbishop and Chancellor Arundel of Canterbury over Lollardy, is Margery Kempe's curate, William Sawtre, whose initial condemnation by Despenser in Lynn, 1399, then his death by being burned in chains as both heretic and traitor in London, was next followed by the promulgation of De heretico comburendo in 1401.

It is generally held that the greater simplicity, childishness and recall of the Amherst Julian Short Text indicates that it was written earlier, immediately after the 1373 'death-bed' vision it describes. While the Long Text's self-proclaimed dating of 1387-1393 is accepted at face value. Scholars have paid little heed to the Amherst date, '1413'. But a study of the 1413 context shows tremendous anxiety, and indeed one medievalist, Rita Copeland, speaks of deliberately instilled 'infantilism' during this period. The drastic changes between the Long Text and the Short Text are that the Long Text gave vast swathes from the Bible in the most exquisite English, while the Short Text excises most of these - as was required by Arundel's 1408 Constitution and for which transgression had been punishable since 1401 with De heretico comburendo , as was indeed done to William Sawtre, Margery Kempe's curate at St Margaret's, Lynn. William Sawtre, through St Margaret's Church, Lynn, is also connected to Adam Easton's Benedictine Priory in Norwich (which also had oversight over Carrow Priory and St Julian's Church) which had its oversight. Julian would probably have known of both Marguerite Porete and of William Sawtre's grim fates.

|| David Wilkins, Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae (London, 1737), III.252-260: William Sawtre first on trial before Bishop Henry Le Despenser of Norwich in Lynn, 1 May 1399, renouncing his errors, amongst them stating Christ in flesh and blood was more worthy of worship than the mere wood of a cross, 25 May 1399; two years later burned, 26 February 1401, as a relapsed heretic, Despenser bringing evidence to his London trial. Augustus Jessop, Diocesan Histories: Norwich (London: SPCK, 1884), pp. 137-138: 1389, Despenser only Bishop suppressing Lollardy; 1399, opposed Henry IV, arrested, imprisoned; 1401, reconciled.|| However, while there was danger, even for anchoresses, for recluses, like Julian, there was also respect. Beachamp's Pageants, written considerably later, in text and image chronicles the Earl of Warwick's participation in military and political events, and includes amongst these the prophecy of the Recluse at York, Emma Raughton, that King Henry VI should be crowned both in England and in France, and that the Earl should found a chantry at the hermitage at Guy's Cliff. The text names her 'Dame Emma Rawhton Recluse at alle hallowes in Northgate strete of York' on the fifth line below:

Pageant XLVII. King Henry VI is crowned king of France in Paris, by his great-uncle, Cardinal Beaufort, 16 December 1430

Another illumination in Beauchamps' Pageants shows the Earl being made a Knight of the Garter after he has been successful in putting down the Lollard uprising, contemporary with the dating of the Amherst manuscript's version of the Showing of Love:

Courtesy of the British Library. Pageant XXIV. Henry V with the lords of his council and Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, in armour, after he had been instrumental in suppressing the Lollard rising, 1414.

JULIAN AND MARGERY: SHOWING AND BOOK

Around the date of '1413', Margery Kempe from Lynn visited Julian in her Norwich Anchorhold and later gave a remarkable account of their conversation together. The two texts, Julian's and Margery's tally, and they especially tally for the '1413' Short Text rather than for the more sophisticated Westminster and Paris/Sloane Long Text Versions whose manuscripts give dates of '1368' and '1387-1393'. Under Arundel there was great danger where a woman anchoress was perceived as subtle and sophisticated in her reasoning. Julian, circa 1413, in response to such exigencies, simplifies and crystallizes her teaching. But she does not fall silent. Comparing Julian's Showing of Love to The Book of Margery Kempe, we especially see Margery's account of her conversation with Julian to centre on the topic both the Short Text and this conversation share, the burning topic of the day, the 'Discerning of Spirits'.

Moreover, in The Book of Margery Kempe, it is not without interest that Margery's visit to Julian is immediately preceded by that to the saintly Carmelite. William Southfield of Norwich: 'a Whyte Frer in the same cyte of Norwyce whech hyte Wyllyam Sowthfeld', who died, 26 August 1414. Margery's spiritual direction comes from Carmelites, such as 'Maystyr Aleyn'. D.D., of Lynn, who compiled indices of St Birgitta's Revelationes, and Dominicans mainly, in the latter case, with close connections to Catherine of Siena through Raymond of Capua.

The comparison of these texts, transcribed directly from their manuscripts is given in The Soul a City: Julian and Margery .

THE AMHERST'S ANNOTATOR

The Amherst Manuscript was later annotated untidily by the Carthusian James Grenehalgh for the Brigittine Joanna Sewell of Syon Abbey.

|| Sargent, Michael G. James Grenehalgh as Textual Critic. Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 1984. Analecta Cartusiana 85. 2 vols. Contains images of Amherst folios with annotations. May be purchased from Professor James Hogg .||

British Library, Amherst Manuscript, Additional 37,790, fol. 108v. By Permission of the British Library. Reproduction Prohibited.

Here we see where the tortured and sinning James Grenehalgh, who marred many contemplative books in this way (he was eventually literally sent to Coventry by his brethren), responds to Julian's text, written out collaboratively between two scribes, one correcting the other and of whom the second may have been Julian herself at 70. Here, Grenehalgh writes untidily in the margin, as well as underlining these words the text, 'contrition', 'confessyon', 'penaunce', and for 'domesmann', 'gostly father'. Julian's discussion of the sacrament of penance looks back to the beginning of her text concerning her desire to know Christ's wounds, and those of St Cecilia, defouling ' the fayre ymage of god' which the original rubricator to the text underlines in red . We recall Julian's anguish about not confessing her vision when one ' growndyd in haly kyrke' suddenly became interested in it, back in May, 1373, now fifty years earlier than this manuscript version's stated date of 1413.

CONCLUSIONS

Francis Blomefield, closer to Julian's time, spoke of Carrow Priory as having been a school for young women. Then Julian had likely earned her keep, Dom Jean Leclercq reminds us, as a grammar teacher of small boys and as a catechism teacher, until Archbishop Arundel's stern prohibition was promulgated against women teaching theology. At which point her name appears in Wills, for she has lost her livelihood and means of support, given the draconian measures against Lollards. We see in the eyeskip corrections to the text a hand that is like a woman's, squarish, a bit amateur, but proficient in Latin abbreviations, nevertheless. We also see in these excerpts from this manuscript that Julian and her text function somewhat like a confession manual, the Middle Ages' psychiatry, probing and healing the wounds of the soul, giving 'comfortable words to Christ's lovers', both women and men, as the male scribe observes above in the introductory preface to her text. In doing so he authorizes her. Indeed, we see in this collection of texts associated with her echoes of such Church Fathers as Dionysius, Augustine and Jerome/Pelagius, and more contemporary theologians such as William Flete and Richard Lavenham. Women were not permitted to teach theology (though in the Early Church women were catechists to women) or to administer the sacraments (and especially not confession), with the exception of baptism, or to translate the Bible into the vernacular (though Paula and Eustochium collaborated with Jerome with the Vulgate from Hebrew and Greek into Latin). Women were, however, honoured for their visions, revelations, showings, from God. Jerome praised those of Paula at Calvary and in Bethlehem. Cardinal Jacques de Vitry supported those of Mary of Oignies, this fact being noted by Birgitta of Sweden's and Margery Kempe's spiritual directors concerning their written revelations. Mary and John were equally shown beneath the now mandatory medieval Roods, representing our stance as women and men who are ' Christ's lovers'. Julian casts her work in the form of the Revelation, the Showing of Love, that she receives in illness from seeing the bleeding Crucifix, but this is frame to her excellent teaching of the catechism concerning the sacraments, especially, in this text, that of penance. The Anchoress in her Norwich Anchorhold is a doctor of the soul to such as Margery Kempe . Even this manuscript's use of a male and clerical scribe may be in response to her need for authorization, given Arundel's 1408_Constitution_. Similarly Margery resorts to male and clerical scribes to authorize her text. (Though I suspect her initial scribe, whom she gives as her son, was her daughter-in-law from Gdansk, where Birgitta's _Revelatione_s were especially cherished, both Margery and her daughter-in-law needing to conceal the gender of the Book's writer.) We see Julian's male scribe, who may be Carmelite, acknowledge Julian's efficacy. We see a male reader, a Carthusian, do the same. Her text attests, like a legal document for a canonization process, to her saintliness. It also functions like a priestly confession manual. Indeed, we still turn to it today for our own soul healing.

THE MANUSCRIPT'S SUBSEQUENT HISTORY

Most Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love manuscripts which survive demonstrate connections with contemplative and Brigittine Syon Abbey, where they were clearly read, annotated and treasured by its Sisters. James Grenehalgh's annotations for Joanna Sewell connect it with Carthusian Shene Charterhouse and Brigittine Syon Abbey. Syon's downfall was to come about through the Benedictine nun from Canterbury, Elizabeth Barton, being encouraged by Dr Edward Bocking, O.S.B., likewise of Canterbury, to come to Syon Abbey and to write there a massive book, her Revelations, modeled on St Birgitta of Sweden's Revelationes , St Catherine of Siena's Dialogo , and other women's books made available to her there in English. In her text she dared to prophesy against Henry VIII's impending marriage to Anne Boleyn. Every copy of her printed book was destroyed by Act of Attainder (25 Henry VIIII c.12), and she and her editor were executed. Following those executions would be that of St Thomas More who also frequented the library of Syon Abbey. The Westminster Cathedral Manuscript florilegium including Julian of Norwich's Showing of Love came into the recusant Lowe family, which continued their strong association with Syon Abbey, despite the drawing, hanging and quartering or imprisonment of several of its members, finding its way to Syon Abbey in Lisbon, then back to England. The Paris Manuscript of the Showing of Love was written out by the Brigittine Sisters in exile in Flanders, then left behind by them in Rouen when they had to flee precipitously to Lisbon. The Norwich Castle Manuscript has remained in Norfolk since its origins. The Amherst Manuscript, the only one by a male scribe, was also the only Showing of Love Manuscript that survives that has remained continuously in England.

Francis Blomefield noted that in his day the manuscript was owned by Francis Peck, a Leicestershire antiquary. It was Francis Blomefield who first discovered the Paston Letters. He responded to Julian's text with the greatest admiration, copying out its incipit, carefully, though erring as to its date, and speaking of her great reputation for holiness:

Here es a Vision schewed be the Goodenes of GOD, to a devoute Woman and hir Name is Julian that is Recluse atte Norwyche, and yitt ys on Life, Anno Domini M.CCCC.XLII. In the whilke Vision er fulle many comfortabyll Wordes & greatly styrrande to alle they that desyres to be CRYSTES LOOVERSE. || Blomefield, Francis. An Essay towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk . . . and other Authentick Memorials. London: William Miller, 1805-10. 11 vols. Volume IV, 1806, 81-3, 524-30. || The British Library Manuscript Room has these volumes rebound, filled with fine watercolour drawings of relevant monuments and artifacts, giving important additional information. See Additional 23,016. || Dom Gabriel Meunier noted that Francis Peck then gave it to Sir Thomas Cave whose library was sold in London, 1758. According to its bookplate, it came to be owned by William Constable. It was purchased 24-27 March 1910 by the British Library at Sotheby's Lord Amherst Sale, Lot 813.

THE MANUSCRIPT'S EDITIONS

Editions: || Revd. Dundas Harford. Comfortable Words for Christ's Lovers. Trans. Revd. Dundas Harford. 1911. || 'A Critical Edition of the Revelations of Julian of Norwich (1342-c.1416), Prepared from All the Known Manuscripts with Introduction, Notes and Select Glossary'. Ed. Frances Reynolds (Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P.), D.Phil., Leeds University, 1956. || A Shewing of God's Love: The Shorter Version of Sixteen Revelations of Divine Love. Trans. Sr Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. London: Longmans Green, 1958.|| A Book of Showings to the Anchoress Julian of Norwich. Ed. Edmund Colledge, O.S.A. and James Walsh, S.J. Toronto: Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies, 1978. Vol. I.|| Julian of Norwich's Revelations of Divine Love: The Shorter Version Ed. from B.L. MS 37790. Ed. Frances Beer. Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1978. ||Showing of Love in the '1413'/1413-1435 British Library Amherst Manuscript. Ed. Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P.and Julia Bolton Holloway. Vol. I:III of the Extant Manuscripts. Italy, 2000. This Project in Progress. The British Library asks, concerning these electronic images of the Amherst Manuscript text, that we state that 'copyright of the images belongs to the British Library and that further reproduction is prohibited'. We invite the participation of scholars in these areas, their additional bibliographical materials, and we encourage the dating of the Short Text being argued in debate.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian ever had. During the war years she was transcribing the extant microfilms with a microscope, a word at a time, for her Leeds University MA and Ph.D. theses. Subsequent editions are based on her meticulous work.

Sister Anna Maria Reynolds C.P. was the greatest editor Julian ever had. During the war years she was transcribing the extant microfilms with a microscope, a word at a time, for her Leeds University MA and Ph.D. theses. Subsequent editions are based on her meticulous work.

Indices to Umilt� Website's Julian Essays:

Preface

Influences on Julian

Her Self

Her Contemporaries

Her Manuscipt Texts **♫with recorded readings of them

About Her Manuscript Texts

After Julian, Her Editors

Julian in our Day

Publications related to Julian:

Saint Bride and Her Book: Birgitta of Sweden's Revelations Translated from Latin and Middle English with Introduction, Notes and Interpretative Essay. Focus Library of Medieval Women. Series Editor, Jane Chance. xv + 164 pp. Revised, republished, Boydell and Brewer, 1997. Republished, Boydell and Brewer, 2000. ISBN 0-941051-18-8

To see an example of a page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

To see an example of a page inside with parallel text in Middle English and Modern English, variants and explanatory notes, click here. Index to this book at http://www.umilta.net/julsismelindex.html

Julian of Norwich. Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation. Edited. Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo (Click on British flag, enter 'Julian of Norwich' in search box), 2001. Biblioteche e Archivi 8. XIV + 848 pp. ISBN 88-8450-095-8.

To see inside this book, where God's words are in red, Julian's in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

To see inside this book, where God's words are in red, Julian's in black, her editor's in grey, click here.

Julian of Norwich. Showing of Love. Translated, Julia Bolton Holloway. Collegeville: Liturgical Press; London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. Amazon ISBN 0-8146-5169-0/ ISBN 023252503X. xxxiv + 133 pp. Index.

To view sample copies, actual size, click here.Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love, Westminster Text, translated into Modern English, set in William Morris typefont, hand bound with marbled paper end papers within vellum or marbled paper covers, in limited, signed edition. A similar version available in Italian translation. To order, click here.

To view sample copies, actual size, click here.Julian of Norwich, Showing of Love, Westminster Text, translated into Modern English, set in William Morris typefont, hand bound with marbled paper end papers within vellum or marbled paper covers, in limited, signed edition. A similar version available in Italian translation. To order, click here.

'Colections' by an English Nun in Exile: Biblioth�que Mazarine 1202. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le Bl�vec. Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 2006.

'Colections' by an English Nun in Exile: Biblioth�que Mazarine 1202. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family. Analecta Cartusiana 119:26. Eds. James Hogg, Alain Girard, Daniel Le Bl�vec. Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 2006.

Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of Norwich and Adam Easton OSB. Analecta Cartusiana 35:20 Spiritualit�t Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 2008. ISBN 978-3-902649-01-0. ix + 399 pp. Index. Plates.

Teresa Morris. Julian of Norwich: A Comprehensive Bibliography and Handbook. Preface, Julia Bolton Holloway. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010. x + 310 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0-7734-3678-7; ISBN-10: 0-7734-3678-2. Maps. Index.

Fr Brendan Pelphrey. Lo, How I Love Three: Divine Love in Julian of Norwich. Ed. Julia Bolton Holloway. Amazon, 2013. ISBN 978-1470198299

Julian among the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016. xxi + 328 pp. VII Plates, 59 Figures. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8894-X, ISBN (13) 978-1-4438-8894-3.

Mary's Dowry; An Anthology of Pilgrim and Contemplative Writings/ La Dote di Maria:Antologie di Testi di Pellegrine e Contemplativi.Traduzione di Gabriella Del Lungo Camiciotto. Testo a fronte, inglese/italiano. Analecta Cartusiana 35:21 Spiritualit�t Heute und Gestern. Salzburg: Institut f�r Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universit�t Salzburg, 2017. ISBN 978-3-903185-07-4. ix + 484 pp.

UMILTA WEBSITE, JULIAN OF NORWICH, HER SHOWING OF LOVE AND ITS CONTEXTS �1997-2024 JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY || JULIAN OF NORWICH || SHOWING OF LOVE || HER TEXTS || HER SELF || ABOUT HER TEXTS || BEFORE JULIAN || HER CONTEMPORARIES || AFTER JULIAN || JULIAN IN OUR TIME || ST BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN || BIBLE AND WOMEN || EQUALLY IN GOD'S IMAGE || MIRROR OF SAINTS || BENEDICTINISM|| THE CLOISTER || ITS SCRIPTORIUM || AMHERST MANUSCRIPT || PRAYER || CATALOGUE AND PORTFOLIO (HANDCRAFTS, BOOKS ) || BOOK REVIEWS || BIBLIOGRAPHY ||