Charles George Gordon (original) (raw)

British general (1833–1885)

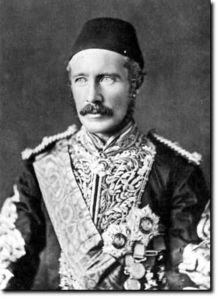

| Charles George Gordon | |

|---|---|

Gordon between 1878 and 1885 Gordon between 1878 and 1885 |

|

| Nickname(s) | Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, Gordon of Khartoum |

| Born | 28 January 1833Woolwich, Kent, England |

| Died | 26 January 1885(1885-01-26) (aged 51)Khartoum, Mahdist Sudan |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service / branch | British ArmyEver Victorious Army |

| Years of service | 1852–1885 |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Commands | Ever Victorious ArmyGovernor-General of the Sudan |

| Battles / wars | Crimean War Siege of Sevastopol Battle of Kinburn Second Opium War Taiping Rebellion Battle of Cixi Battle of Changzhou Mahdist War Siege of Khartoum † |

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom)Order of the Osmanieh, Fourth Class (Ottoman Empire)Order of the Medjidie, Fourth Class (Ottoman Empire)Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (France)Order of the Double Dragon (China)Imperial yellow jacket (China) |

| Signature |  |

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in the British Army. However, he made his military reputation in China, where he was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army", a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers which was instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese Gordon" and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

He entered the service of the Khedive of Egypt in 1873 (with British government approval) and later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the local slave trade. He then resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

A serious revolt then broke out in the Sudan, led by a Muslim religious leader and self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. In early 1884, Gordon was sent to Khartoum with instructions to secure the evacuation of loyal soldiers and civilians and to depart with them. In defiance of those instructions, after evacuating about 2,500 civilians, he retained a smaller group of soldiers and non-military men. In the months before the fall of Khartoum, Gordon and the Mahdi corresponded; Gordon offered him the sultanate of Kordofan and the Mahdi requested Gordon to convert to Islam and join him, which Gordon declined. Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organised a citywide defence that lasted for almost a year and gained him the admiration of the British public, but not of the government, which had wished him not to become entrenched there. Only when public pressure to act had become irresistible did the government, with reluctance, send a relief force. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

Gordon was born in Woolwich, Kent, a son of Major General Henry William Gordon (1786–1865) and Elizabeth (1792–1873), daughter of Samuel Enderby Junior. The men of the Gordon family had served as officers in the British Army for four generations, and as a son of a general, Gordon was raised to be the fifth generation; the possibility that Gordon would pursue anything other than a military career seems never to have been considered by his parents.[1] All of Gordon's brothers also became Army officers.[1]

Gordon grew up in England, Ireland, Scotland, and the Ionian Islands (which were under British rule until 1864) as his father was moved from post to post.[2] He was educated at Fullands School in Taunton, Taunton School, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich.[3]

In 1843, Gordon was devastated when his favourite sibling, his sister Emily, died of tuberculosis, writing years later, "humanly speaking it changed my life, it was never the same since".[4] After her death, her place as Gordon's favourite sibling was taken by his very religious older sister Augusta, who nudged her brother towards religion.[5]

As a teenager and an army officer cadet, Gordon was known for his high spirits, a combative streak, and tendency to disregard authority and the rules if he felt them to be stupid or unjust, a personality trait that held back his graduation by two years when teachers decided to punish him for flouting the rules.[6]

As a cadet, Gordon displayed exceptional talents at map-making and in designing fortifications, which led to his career choice of the Royal Engineers or "sappers" in the Army.[7] He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers on 23 June 1852,[8] completing his training at Chatham, and he was promoted to full lieutenant on 17 February 1854.[9] The sappers were an elite corps who performed reconnaissance work, led storming parties, demolished obstacles in assaults, and undertook rear-guard actions in retreats and other hazardous tasks.[10]

As an officer, Gordon showed strong charisma and leadership, but his superiors distrusted him on account of his tendency to disobey orders if he felt them to be wrong or unjust.[7] A man of medium stature, with striking blue eyes, the charismatic Gordon had the ability to inspire men to follow him anywhere.[11]

Gordon was first assigned to construct fortifications at Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, Wales. During his time in Milford Haven, Gordon was befriended by a young couple, Francis and Anne Drew, who introduced him to evangelical Protestantism.[12] Gordon was especially impressed with Philippians 1:21 where St. Paul wrote: "For to me, to live is Christ, and to die is gain", a passage he underlined in his Bible and often quoted.[12] He attended diverse congregations, including Roman Catholic, Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist. Gordon, who once said to a Roman Catholic priest that "the church is like the British Army, one army but many regiments", never aligned himself with or became a member of any church.[13]

From Crimea to the Danube

[edit]

When the Crimean War began, Gordon was assigned to his boyhood home of Corfu, but after several letters to the War Office, he was sent to Crimea instead.[14] He was sent to the Russian Empire, arriving at Balaklava in January 1855. He first displayed his death wish as he wrote at the time that he had gone "to the Crimea, hoping, without having a hand in it, to be killed".[15]

In the 19th century, Russia was Britain's archenemy, with many people in both nations seeing an ideological conflict between Russian autocracy and British democracy, and Gordon was anxious to fight in the Crimea.[15] He was put to work in the Siege of Sevastopol and took part in the assault of the Redan from 18 June to 8 September. As a sapper, Gordon had to map out the Russian fortifications at the city-fortress of Sevastopol, designed by the famous Russian military engineer, Eduard Totleben. It was a highly dangerous job that frequently put him under enemy fire, and led to him being wounded for the first time when a Russian sniper put a bullet into him.[16] Gordon spent much time in "the Quarries", as the British called their section of the trenches, facing Sevastopol.[16]

During his time in Crimea, Gordon made friendships that were to last for the rest of his life, most notably with Romolo Gessi, Garnet Wolseley, and Gerald Graham, all of whom would cross paths with Gordon several times in the future.[16]

On 18 June 1855, the besieging British and French armies began what was intended to be the final assault that would take Sevastopol, which began with a huge bombardment. As a sapper, Gordon was in a front line trench where he was under intense fire, men fell all around him, and he was forced to take cover so often that he was covered literally from head to toe with mud and blood.[17] Despite the best efforts of the Allies, the French failed to take the Malakhov fortress, while the British failed to take the Redan fortress on 18 June.[17] The casualties on the Allied side were quite high that day.[17]

Gordon spent thirty-four consecutive days in the trenches around Sevastopol, and earned a reputation as an able and brave young officer.[18] It was said at the British HQ that, "If you want to know what the Russians are up to, send for Charlie Gordon."[18]

Gordon took part in the expedition to Kinburn, and returned to Sevastopol at the war's end. During the Crimean war, Gordon picked up an addiction to Turkish cigarettes which was to last for his rest of his life, and many commented that smoking was Gordon's most conspicuous vice as he always seemed to have a cigarette at his lips.[19]

For his services in Crimea, he received the Crimean war medal and clasp.[3] For the same services, he was appointed a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour by the Government of France on 16 July 1856.[20]

Gordon, from a photograph taken shortly after the Crimea.

Following the peace, he was attached to an international commission to mark the new border between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire in Bessarabia. When Gordon first arrived in the city of Galatz (modern Galați, Romania) in the Ottoman protectorate of Moldavia, he called the city "very dusty and not desirable at all as a place of residence".[21] As he travelled to Bessarabia, he commented in his letters home about the richness and fertility of the Romanian countryside, which produced delicious fruits and vegetables in great abundance, and the poverty of the Romanian peasants.[22]

After a visit to Jassy (modern Iași), Gordon wrote: "The boyers live most of their lives in Paris and society is quite French... The prince keeps a great state, and I was introduced to him with much ceremony. The English uniform produces an immediate sensation".[23] Gordon did not speak Romanian, but his fluency in French allowed him to socialise with the Francophile Romanian elite, who were all fluent in French.[24] As the maps that delineated the Russian-Ottoman frontier were all old and inaccurate, Gordon spent much time clashing with his Russian counterparts about where precisely the frontier was and soon discovered that the Russians were very keen to have the frontier on the Danube, which Gordon had orders from London to prevent.[24] Gordon called the Romanians the "most fickle and intriguing people on the earth. They ape the French in everything and are full of ceremony, dress, etc... The employees sent by the Moldovan government to take over the ceded territory have been receiving bribes and trafficking in the most disgraceful manner."[25]

Afterwards, Gordon was sent to delineate the frontier between Ottoman Armenia and Russian Armenia, the highlight of which was tobogganing down Mount Ararat.[26] Gordon continued surveying, marking off the boundary into Asia Minor. During his time in Anatolia, Gordon embraced the new technology of the camera to take what the Canadian historian C. Brad Faught called a series of "evocative photographs" of the people and landscape of Armenia.[26] Throughout his life, Gordon was always a keen amateur photographer and was elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society to honour him for his Armenian photographs.[27] Gordon returned to Britain in late 1858, and was appointed as an instructor at Chatham. He was promoted to captain on 1 April 1859.[28]

Charles Gordon as a tidu (Captain General).

Gordon was bored with garrison duty in Chatham and often wrote to the War Office, begging them to send him anywhere in the world where British arms were seeing action.[29] In 1860, Gordon volunteered to serve in China, in the Second Opium War.[30] When Gordon arrived at Hong Kong, he was disappointed to learn he was "just too late for the fighting".[31] Gordon had heard of the Taiping Rebellion long before he had set sail for China, and he was at first sympathetic towards the Taipings, led by Hong Xiuquan, who proclaimed himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ, viewing them as somewhat eccentric Christians.[31]

After stopping in Shanghai, Gordon visited the Chinese countryside and was appalled at the atrocities committed by the Taipings against the local peasants, writing to his family he would love to smash this "cruel" army with its "desolating presence" that killed without mercy.[31] He arrived at Tianjin in September 1860. He was present during the capture of Peking and at the destruction of the Summer Palace. Gordon agreed with Lord Elgin that after the Chinese authorities had murdered a group of British and French officers travelling under a white flag to parley that a reprisal was in order, but called the burning of the Summer Palace "vandal-like" and informed his sister in a letter that "it made one's heart sore" to burn it.[32] The Anglo-French force remained in northern China until April 1862, then, under General Charles William Dunbar Staveley, withdrew to Shanghai to protect the European settlement from the rebel Taiping army.[33]

Following the successes in the 1850s in the provinces of Guangxi, Hunan, and Hubei, and the capture of Nanjing in 1853, the rebel advance had slowed. For some years, the Taipings gradually advanced eastwards, but eventually they came close enough to Shanghai to alarm the European inhabitants. A militia of Europeans and Asians was raised for the defence of the city and placed under the command of an American, Frederick Townsend Ward, and occupied the country to the west of Shanghai.[34] The British arrived at a crucial time. Staveley decided to clear the rebels within 30 miles (48 km) of Shanghai in co-operation with Ward and a small French force.[34] Gordon was attached to his staff as engineer officer. Jiading, northwest suburb of present Shanghai, Qingpu, and other towns were occupied, and the area was fairly cleared of rebels by the end of 1862.[34]

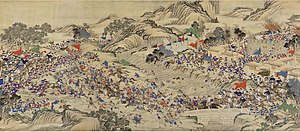

A scene of the Taiping Rebellion. Estimates of the war dead from the Taiping Rebellion range from 20 to 70 million to as high as 100 million.[35]

Ward was killed in the Battle of Cixi and his successor H. A. Burgevine, an American, was disliked by the Imperial Chinese authorities.[36] Burgevine was an unsavory character known for his greed and alcoholism.[37] Moreover, Burgevine made little effort to hide his racism, and his relations with the Chinese were very difficult at the best of times.[37] Li Hongzhang, the governor of the Jiangsu province, requested Staveley to appoint a British officer to command the contingent. Staveley selected Gordon, who had been made a brevet major in December 1862 and the nomination was approved by the British government.[36] Given Burgevine's alcoholism, open corruption, and tendency to engage in acts of mindless violence when drunk, the Chinese wanted "a man of good temper, of clean hands, and a steady economist" as his replacement.[38] These requirements led Staveley to choose Gordon.[38] Li was impressed with Gordon, writing:

It is a direct blessing from Heaven, the coming of this British Gordon. ... He is superior in manner and bearing to any of the foreigners whom I have come into contact with, and does not show outwardly that conceit which makes most of them repugnant in my sight...What an elixir for a heavy heart-to see this splendid Englishman fight! ... If there is anything that I admire nearly as much as the superb scholarship of Zeng Guofan, it is the military qualities of this fine officer. He is a glorious fellow!...With his many faults, his pride, his temper, and his never-ending demand for money—but he is a noble man, and in spite of all I have said to him or about him, I will ever think most highly of him. ... He is an honest man, but difficult to get on with.[39]

Gordon was honest and incorruptible, and unlike many Chinese officers, did not steal the money that was meant to pay his men, but rather insisted on paying the Ever Victorious Army on time and in full.[39] Gordon's insistence on paying his men meant that he was always pressing the Imperial government for money, something which often irritated the mandarins who did not understand why Gordon did not just let his men loot and plunder as a compensation for wages.[39] Gordon designed the uniform for the Ever Victorious Army, which consisted of black boots together with turbans, jackets, and trousers that were all green, while his personal bodyguard of 300 men wore blue uniforms.[40]

Command of the Ever Victorious Army

[edit]

In March 1863, Gordon took command of the force at Songjiang, which had received the name of "Ever Victorious Army".[36] Without waiting to reorganise his troops, Gordon led them at once to the relief of Changsu, a town 40 miles northwest of Shanghai. The relief was successfully accomplished and Gordon quickly won the respect of his troops. Gordon made a point of treating POWs well to encourage the Taipings to surrender, and many of his men were former Taipings who chose to enlist in the Ever Victorious Army.[38] Unlike Ward and Burgevine, Gordon realised that the network of canals and rivers that divided the Chinese countryside were not obstacles blocking an advance, but were rather "arteries" for allowing an advance as Gordon decided to move his men and supplies via the waterways.[41]

Gordon's task was made easier by innovative military ideas Ward had implemented in the Ever Victorious Army. Gordon was quite critical of the way Chinese generals fought the war, observing that the Chinese were willing to inflict and accept gargantuan losses in battle, an approach Gordon disapproved of.[42] Gordon wrote: "The great thing...is to cut off their retreat, and the chances are they will go without trouble; but attack them in the front, and leave their rear open, and they fight most desperately".[42] Gordon always preferred to outflank the Taiping lines rather than to take them on frontally, an approach that caused much tension with his counterparts in the Chinese Imperial Army who did not share Gordon's horror at the huge numbers of casualties caused by frontal assaults.[42]

On the morning of 30 May 1863, the Taiping forces guarding the town of Quinsan were astonished to see an armoured paddle steamer, the Hyson, armed with a 32-pounder cannon on the bow, sailing up a canal, at whose prow stood Gordon. Following the Hyson was a fleet of 80 junks converted to gunboats.[43] Aboard the Hyson were 350 men from the elite 4th Regiment of the Ever Victorious Army.[42] Under fire from the Taiping forces, Gordon's men chopped up the wooden stakes the Taipings had placed in the canal, thereby allowing Gordon to outflank the main Taiping defence line and to enter the main canal connecting Quinsan to Suzhou.[42]

Gordon's breakthrough caught the rebel army off guard and caused thousands of the enemy to panic and flee.[42] Gordon disembarked the 4th Regiment with orders to take Quinsan while he sailed up and down the main canal in the Hyson, using the 32-pounder gun to blast apart the Taiping positions on the canal.[42] At times, Gordon feared that assaults by the Taiping would take the Hyson, but all the attacks were repulsed.[44] The next day, Quinsan fell to the 4th Regiment, which led a proud Gordon to write: "The rebels did not know its importance until they lost it".[45]

In its last years, the Taiping movement had oppressed the Chinese peasantry and as the Taipings retreated in the face of fire from the Hyson, Chinese peasants emerged from their homes to cut down and hack to death the fleeing Taipings.[45] After the battle, Gordon was hailed as a liberator from the Taipings by the ordinary Chinese people.[45] One British officer serving with the Ever Victorious Army described Gordon at this time as: "a light-built, wiry, middle-sized man, of about thirty two years of age, in the undress uniform of the Royal Engineers. The countenance bore a pleasant frank appearance, eyes light blue with a fearless look in them, hair crisp and inclined to curl, conversation short and decided".[46]

The Ever Victorious Army was entirely a mercenary force whose only loyalty was to money and whose men were interested in fighting only in order to gain the chance to plunder.[46] Gordon felt very uncomfortable commanding this force and at one point had to order the summary execution of one of his officers when the latter tried to take the Ever-Victorious Army over to the Taipings, who had offered a generous bribe for switching sides.[46] Gordon had to impose strict discipline on the Ever Victorious Army and worked hard to prevent the Army from engaging in its tendency to loot and mistreat civilians.[39]

Gordon also had the pleasure of defeating Burgevine (whom Gordon detested), who had raised a mercenary force and joined the Taipings.[47] After Gordon had surrounded Burgevine's force outside of Suzhou, the latter had abandoned his own men and attempted to rejoin the Imperial side, leading Gordon to arrest him and send him to the American consul in Shanghai together with a letter asking that Burgevine be expelled from China.[48]

As Gordon travelled up and down the Yangtze River valley, he was appalled by the scenes of poverty and suffering he saw, writing in a letter to his sister: "The horrible furtive looks of the wretched inhabitants hovering around one's boats haunts me, and the knowledge of their want of nourishment would sicken anyone; they are like wolves. The dead lie where they fall, and are, in some cases, trodden quite flat by passers by".[46] The suffering of the Chinese people strengthened Gordon's faith, as he argued that there had to be a just, loving God who would one day redeem humanity from all this wretchedness and misery.[39]

During his time in China, Gordon was well-known and respected by friend and foe alike for leading from the front and going into combat armed only with his rattan cane (Gordon always refused to carry a gun or a sword), a choice of weapon that almost cost him his life several times.[39] Gordon's bravery in battle, his string of victories, apparent immunity to bullets and his intense, blazing blue eyes led many Chinese to believe that Gordon had supernatural powers and had harnessed the Qi (the mystical life-force traditionally believed in China to govern everything) in some extraordinary way.[42]

Gordon then reorganised his force and advanced against Kunshan, which was captured at considerable loss. Gordon then took his force through the country, seizing towns until, with the aid of Imperial troops, capturing the city of Suzhou in November.[36] After its surrender, Gordon personally guaranteed that any Taiping rebel who laid down his arms would be humanely treated.[49] The Ever-Victorious Army—which was inclined to looting—had been ordered not to enter Suzhou, and only Imperial forces entered the city.[46] Gordon was thus powerless when the Imperial forces executed all of the Taiping POWs, an act that enraged him.[50]

A furious Gordon wrote that executing POWs was "stupid", writing, "if faith had been kept, there would have been no more fighting as every town would have given in".[50] In China, the penalty for rebellion was death. Under the Chinese system of familial responsibility, all family members of a rebel were equally guilty even if they had nothing to do with the rebellious individual's acts. The mandarins were thus much inclined to execute not only Taipings, but also their spouses, children, parents, and siblings as being all equally guilty of treason.[50]

Gordon believed this approach was militarily counterproductive, as it encouraged the Taipings to fight to the death, which Gordon felt to be very unwise as the Taiping leader Hong Xiuquan, had become murderously paranoid, conducting bloody purges of his followers. Many Taipings were willing to surrender only if the Imperial government would spare their lives and those of their families. Even more importantly, Gordon had given his word of honour that all of the Taipings who surrendered would be well-treated, and regarded the massacre as a stain on his honour.[50]

On 1 January 1864, Gordon was informed that a messenger from the Tongzhi Emperor was coming to see him and that he should put on his finest uniform.[50] When the Emperor's messenger arrived, he had with him servants carrying boxes of silver taels (coins) numbering 10,000 in total, together with banners written in the most eloquent calligraphy celebrating Gordon as a great general and a letter from the Emperor himself written in the best calligraphy on yellow silk thanking Gordon for taking Suzhou and offering all these presents as rewards.[50]

Gordon refused all these gifts and wrote on the Emperor's silk message: "Major Gordon receives the approbation of His Majesty the Emperor with every gratification, but regrets most sincerely that owing to the circumstances which occurred since the capture of Soochow, he is unable to receive any mark of His Majesty the Emperor's recognition".[50] The Emperor was much offended when he received Gordon's message at the Forbidden City, and Gordon's military career in China was effectively over for a time.[50] A Scotsman who knew Gordon in China wrote: "he shows the Chinese that if even an able and reliable man, such as he is, is unmanageable".[50] Following a dispute with Li over the execution of rebel leaders, Gordon withdrew his force from Suzhou and remained inactive at Kunshan until February 1864.[36]

Gordon then made a rapprochement with Li and visited him in order to arrange for further operations. The "Ever-Victorious Army" resumed its high tempo advance, leading to the Battle of Changzhou, and culminating in the capture of Changzhou Fu, the principal military base of the Taipings in the region. Gordon wrote in his diary: "The HOUR GLASS BROKEN" and predicted that the war would soon be won.[51] The Ever Victorious Army did not take part in the final offensive that ended the war with the Capture of Nanking as the "Imps", as Gordon called the Imperial Army, wanted the honour of taking Nanking, the Taiping capital, for themselves.[51]

Capture of Yesing, Liyang, and Kitang

[edit]

Instead, the Ever Victorious Army was given the task of taking the secondary cities of Yesing, Liyang, and Kitang.[51] At Kitang, Gordon was wounded for the second time on 21 March 1864, when a Taiping soldier shot him in the thigh. The wound was only slight and Gordon was soon back in action, fighting his last battle at Chang-chou in May 1864.[51] Gordon then returned to Kunshan and disbanded his army in June 1864.[50] During his time with the Ever Victorious Army, Gordon had won thirty-three battles in succession.[50] Gordon wrote a letter home that his losses were "no joke" as 48 of his 100 officers and about 1,000 of 3,500 soldiers had been killed or wounded in action.[52]

The Emperor promoted Gordon to the rank of tidu (提督: "Chief commander of Jiangsu province" – a title equal to field marshal), decorated him with the imperial yellow jacket, and raised him to Qing's Viscount first class, but Gordon declined an additional gift of 10,000 taels of silver from the imperial treasury.[53][54] Only forty men were allowed to wear the Yellow Jacket, which was the Emperor's ceremonial bodyguard, and it was thus a signal honour for Gordon to be allowed to wear it.[55] The British Army promoted Gordon to lieutenant-colonel on 16 February 1864,[56] and he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath on 9 December 1864.[57]

The traders of Shanghai offered Gordon huge sums of money to thank him for his work commanding the Ever Victorious Army. Gordon declined all honours of financial gain, writing: "I know I shall leave China as poor as I entered it, but with the knowledge that, through my weak instrumentality, upwards of eighty to one hundred thousand lives have been spared. I want no further satisfaction than this".[55] The British journalist Mark Urban, wrote: "People saw a brave man who acted with humanity in an otherwise ghastly conflict, standing out from the other mercenaries, adventurers, and cut-throats in wanting almost nothing for himself".[55]

In a leader in August 1864, The Times wrote about Gordon: "the part of the soldier of fortune is in these days very difficult to play with honour...but if ever the actions of a soldier fighting in foreign service ought to be viewed with indulgence, and even with admiration, this exceptional tribute is due to Colonel Gordon".[55] The Taiping Rebellion attracted much media attention in the West, and Gordon's command of the Ever Victorious Army received much coverage from British newspapers.[55] Gordon also gained the popular nickname, "Chinese" Gordon.[55]

Service with the Khedive

[edit]

From the Danube to the Nile

[edit]

In October 1871, he was appointed British representative on the international commission to maintain the navigation of the mouth of the River Danube, with headquarters at Galatz. Gordon was bored with the work of the Danube commission, and spent as much time as possible exploring the Romanian countryside, whose beauty enchanted Gordon when he was not making visits to Bucharest to meet up with his old friend Romolo Gessi, who was living there at the time.[58] During his second trip to Romania, Gordon insisted on living with ordinary people as he travelled over the countryside, commenting that Romanian peasants "live like animals with no fuel, but reeds", and spent one night at the home of a poor Jewish craftsman whom Gordon praised for his kindness in sharing the single bedroom with his host, his wife, and their seven children.[59] Gordon seemed pleased by his simple lifestyle, writing in a letter that: "One night, I slept better than I have for a long time, by a fire in a fisherman's hut".[59]

During a visit to Bulgaria, Gordon and Gessi become involved in an incident when a Bulgarian couple told them that their 17-year-old daughter had been abducted into the harem of an Ottoman pasha, and asked them to free their daughter.[60] Popular legend has it that Gordon and Gessi broke into the pasha's palace at night to rescue the girl, but the truth is less dramatic.[60] Gordon and Gessi demanded that Ahmed Pasha allow them to meet the girl alone, had their request granted after much arm-twisting, and then met the girl, who ultimately revealed she wanted to go home.[61] Gordon and Gessi threatened to go to the British and Italian press if she was not released at once, a threat that proved sufficient to win the girl her freedom.[61]

Gordon was promoted to colonel on 16 February 1872.[62] In 1872, Gordon was sent to inspect the British military cemeteries in the Crimea, and when passing through Constantinople, he made the acquaintance of the Prime Minister of Egypt, Raghib Pasha. The Egyptian Prime Minister opened negotiations for Gordon to serve under the Ottoman Khedive, Isma'il Pasha, who was popularly called "Isma'il the Magnificent" on the account of his lavish spending. In 1869, Isma'il spent 2 million Egyptian pounds (the equivalent to $300 million U.S. dollars in today's money) just on the party to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal, in what was described as the party of the century.[63] In 1873, Gordon received a definite offer from the Khedive, which he accepted with the consent of the British government, and proceeded to Egypt early in 1874. After meeting Gordon in 1874, the Khedive Isma'il had said: "What an extraordinary Englishman! He doesn't want money!".[64]

The French-educated Isma'il Pasha greatly admired Europe as the model for excellence in everything, being an especially passionate Italophile and Francophile, saying at the beginning of his reign: "My country is no longer in Africa, it is now in Europe".[65] Isma'il was a Muslim who loved Italian wine and French champagne, and many of his more conservative subjects in Egypt and the Sudan felt alienated by a regime that was determined to Westernise the country with little regard for tradition.[65] The languages of Khedive's court were Turkish and French, not Arabic. The Khedive's great dream was to make Egypt culturally a part of Europe, and he spent huge sums of money attempting to modernise and Westernise Egypt, in the process going very deeply into debt.[66]

At the beginning of his reign in 1863, Egypt's debt had been 3 million Egyptian pounds. When Isma'il's reign ended in 1879, Egypt's debt had risen to 93 million pounds.[67] During the American Civil War, when the Union blockade had cut off the American South from the world economy, the price of Egyptian cotton, known as "white gold" had skyrocketed as British textile mills turned to Egypt as an alternative source of cotton, causing an economic blossoming of Egypt that ended abruptly in 1865.[66] As the attempts of his grandfather—Muhammad Ali the Great—to depose the ruling Ottoman family in favour of his own family had failed due to the opposition of Russia and Britain, the imperialistic Ismai'il had turned his attention southwards and was determined to build an Egyptian empire in Africa, planning on subjugating the Great Lakes region and the Horn of Africa.[68] As part of his Westernisation programme, Isma'il often hired Westerners to work in his government both in Egypt and in the Sudan. Ismai'il's Chief of General Staff was the American general Charles Pomeroy Stone, and other veterans of the American Civil War were commanding Egyptian troops.[69] Urban wrote that most of the Westerners in Egyptian pay were "misfits" who took up Egyptian service because they were unable to get ahead in their own nations.[70]

Typical of the men that Khedive Isma'il Pasha hired was Valentine Baker, a British Army officer dishonorably discharged after being convicted of raping a young woman in England that he had been asked to chaperon. After Baker's release from prison, Isma'il hired him to work in the Sudan.[71] John Russell, the son of the famous war correspondent William Howard Russell, was another European recruited to serve on Gordon's staff.[72] The younger Russell was described by his own father as an alcoholic and spendthrift who "was beyond help" as it was always the "same story-idleness, self-indulgence, gambling, and constant promises" broken time after time, leading his father to get him a job in the Sudan, where his laziness infuriated Gordon to no end.[72]

Equatoria: Building Egypt's empire in the Great Lakes region

[edit]

General Gordon in Egyptian uniform.

The Egyptian authorities had been extending their control southwards since the 1820s. Right up to 1914, Egypt was officially a vilayet (province) of the Ottoman Empire, but after Mohammed Ali become the vali (governor) of Egypt in 1805, Egypt was a de facto independent state where the authority of the Ottoman Sultan was more nominal than real. An expedition was sent up the White Nile, under Sir Samuel Baker, which reached Khartoum in February 1870 and Gondokoro in June 1871. Baker met with great difficulties and managed little beyond establishing a few posts along the Nile.[73]

The Khedive asked for Gordon to succeed Baker as the governor of Equatoria province that comprised much of what is today South Sudan and northern Uganda.[73] Isma'il Pasha told Gordon that he wished to expand Equatoria into the rest of Uganda, with the ultimate aim of absorbing the entire Great Lakes region of East Africa into the empire that Isma'il wanted to build in Africa.[74] Baker's annual salary as governor of Equatoria had been £10,000 (Egyptian pounds, about US$1 million in today's money) and Ismail was astonished when Gordon refused that salary, saying that £2,000 per year was more than enough for him.[75]

After a short stay in Cairo, Gordon proceeded to Khartoum via Suakin and Berber. In Khartoum, Gordon attended a dinner with the Governor-General, Ismail Aiyub Pasha, entertained with barely dressed belly dancers whom one of Gordon's officers drunkenly attempted to have sex with, leading to a disgusted Gordon walking out, saying he was shocked that Aiyub allowed these things to happen in his palace.[76] Joining Gordon on the journey to Equatoria was his old friend Romolo Gessi and a former US Army officer, Charles Chaillé-Long, who did not get along well with Gordon.[75]

From Khartoum, he proceeded up the White Nile to Gondokoro. During his time in Sudan, Gordon was much involved in attempting to suppress the slave trade while struggling against a corrupt and inefficient Egyptian bureaucracy that had no interest in suppressing the trade.[77] Gordon soon learned that his superior, the Governor-General of the Sudan, Ismail Aiyub Pasha, was deeply involved in the slave trade and was doing everything within his power to sabotage Gordon's anti-slavery work by denying him supplies and leaking information to the slavers.[78] Gordon also clashed with Chaillé-Long, whom he accused of working as an informant for Aiyub Pasha and called him to his face a "regular failure".[79] Chaillé-Long in return painted a very unflattering picture of Gordon in his 1884 book The Three Prophets, whom he portrayed as a bully, a raging alcoholic, an incompetent leader, and a rank coward.[79] Faught argued that since no one else who knew Gordon in Equatoria described him in these terms, and given that Gordon's accusation that Chaillé-Long was a spy for Aiyub Pasha seems to be justified, that Chaillé-Long was engaging in character assassination as an act of revenge.[79]

Gordon, despite his position as an official in the Ottoman Empire, found the Ottoman-Egyptian system of rule inherently oppressive and cruel, coming into increasing conflict with the very system he was supposed to uphold, later stating about his time in the Sudan, "I taught the natives they had a right to exist".[64] In the Ottoman Empire, power was exercised via a system of institutionalised corruption where officials looted their provinces via heavy taxes and by demanding kickbacks known as baksheesh; some of the money went to Constantinople with the rest being pocketed by the officials.[77]

Gordon established a close rapport with the African peoples of Equatoria such as the Nuer and Dinka, who had long suffered from the activity of Arab slave traders, and who naturally supported Gordon's efforts to stamp out the slave trade.[73] The peoples of Equatoria had traditionally worshipped spirits present in nature, but were steadily being converted to Christianity by missionaries from Europe and the United States, which further encouraged Gordon in his efforts as governor of Equatoria, who notwithstanding his position working for the Egyptian government, saw himself as doing God's work in Equatoria.[73] Gordon was not impressed with the forces of the Egyptian state. The soldiers of the Egyptian Army were fallāḥīn (peasant) conscripts who were both ill-paid and ill-trained.[73] The other force for law and order were the much-feared bashi-bazouks, irregulars who were not paid a salary, but were expected to support themselves by looting. The bashi-bazouks were extremely susceptible to corruption and were notorious for their brutality, especially to non-Muslims.[70]

Gordon remained in the Equatoria province until October 1876. He quickly learned that before he could establish stations to crush the slave trade, he would have to first explore the area to find the best places for building them.[80] A major problem for Gordon was malaria, which decimated his men, and led him to issue the following order: "Never let the mosquito curtain out of your sight, it is more valuable than your revolver".[80] The heat greatly affected Gordon as he wrote to his sister Augusta, "This is a horrid climate, I seldom if ever get a good sleep".[79]

Gordon had succeeded in establishing a line of way stations from the Sobat confluence on the White Nile to the frontier of Uganda, where he proposed to open a route from Mombasa. In 1874, he built the station at Dufile on the Albert Nile to reassemble steamers carried there past rapids for the exploration of Lake Albert. Gordon personally explored Lake Albert and the Victorian Nile, pushing on through the thick, humid jungle and steep ravines of Uganda amid heavy rains and vast hordes of insects in the summer of 1876 with an average daily temperature of 95 °F (35 °C), down to Lake Kyoga.[81] Gordon wrote in his diary, "It is terrible walking ... it is simply killing ... I am nearly dead".[81]

Besides acting as an administrator and explorer, Gordon had to act as a diplomat, dealing carefully with Muteesa I, the Kabaka (king) of the Buganda, who ruled most of what is today southern Uganda, a man who did not welcome the Egyptian expansion into the Great Lakes region.[82] Gordon's attempts to establish an Egyptian garrison in the Buganda had been stymied by the cunning Muteesa, who forced the Egyptians to build their fort at his capital of Lubaga, making the 140 or so Egyptian soldiers his virtual hostages.[81] Gordon chose not to meet Muteesa himself, instead sending his chief medical officer, a German convert to Islam, Dr. Emin Pasha, to negotiate a treaty wherein in exchange for allowing the Egyptians to leave the Buganda, the independence of the kingdom was recognised.[83]

Moreover, considerable progress was made in the suppression of the slave trade.[84] Gordon wrote in a letter to his sister about the Africans living a "life of fear and misery", but in spite of the "utter misery" of Equatoria that, "I like this work".[85] Gordon often personally intercepted slave convoys to arrest the slavers and break the chains of the slaves, but he found that the corrupt Egyptian bureaucrats usually sold the freed Africans back into slavery, and the expense of caring for thousands of freed slaves who were a long away from home burdensome.[86]

Gordon grew close to the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, an evangelical Christian group based in London dedicated to ending slavery all over the world, and who regularly celebrated Gordon's efforts to end slavery in the Sudan. Urban wrote that, "Newspaper readers in Bolton or Beaminister had become enraged by stories about chained black children, cruelly abducted, being sold into slave markets", and Gordon's anti-slavery efforts contributed to his image as a saintly man.[64]

Gordon had come into conflict with the Egyptian governor of Khartoum and Sudan over his efforts to ban slavery. The clash led to Gordon informing the Khedive that he did not wish to return to the Sudan, and he left for London. During his time in London, he was approached by Sir William Mackinnon, an enterprising Scottish ship owner who had gone into partnership with King Leopold II of the Belgians with the aim of creating a chartered company that would conquer central Africa, and wished to employ Gordon as their agent in Africa.[87]

He accepted their offer, believing in Leopold's and Mackinnon's assurances their plans were purely philanthropic and they had no interest in exploiting Africans for profit[88] but the Khedive Isma'il Pasha wrote to him saying that he had promised to return, and that he expected him to keep his word.[89] Gordon agreed to return to Cairo, and was asked to take the position of Governor-General of the entire Sudan, which he accepted. He thereafter received the honorific rank and title of pasha in the Ottoman aristocracy.[90]

Governor-General of the Sudan

[edit]

Besides working to end slavery, Gordon carried out a series of reforms such as abolishing torture and public floggings where those opposed to the Egyptian state were flogged with a whip known as the kourbash made of buffalo hide.[91]

The Europeans whom the Egyptians had hired to work as civil servants in the Sudan proved to be just as corrupt as the Egyptians.[70] The bribes that the slave traders offered for bureaucrats to turn a blind eye to the slave trade had far more effect on the bureaucrats than did any of Gordon's orders to suppress the slave trade, which were simply ignored.[70] Licurgo Santoni, an Italian hired by the Egyptian state to run the Sudanese post office, wrote about Gordon's time as Governor-General that:

as his exertions were not supported by his subordinates, his efforts remained fruitless. This man's activity with the scientific knowledge which he possesses is doubtless able to achieve much, but unfortunately, no one backs him up and his orders are badly carried out or altered in such a way as to render them without effect. All the Europeans, with some rare exceptions, whom he has honoured with his confidence have cheated him.[70]

Relations between Egypt and Abyssinia (later renamed Ethiopia) had become strained due to a dispute over the district of Bogos, and war broke out in 1875. An Egyptian expedition was completely defeated near Gundet. A second and larger expedition under Prince Hassan was sent the following year and was routed at Gura. Matters then remained quiet until March 1877, when Gordon proceeded to Massawa, hoping to make peace with the Abyssinians. He went up to Bogos and wrote to the king proposing terms. He received no reply as the king had gone southwards to fight with the Shoa. Gordon, seeing that the Abyssinian difficulty could wait, proceeded to Khartoum.[92]

In 1876, Egypt went bankrupt. A group of European financial commissioners led by Evelyn Baring took charge of the Egyptian finances in an attempt to pay off the European banks who had lent so much money to Egypt. With Egypt bankrupt, the money to carry out the reforms Gordon wanted was not there.[64] With over half of Egypt's income going to pay the 7% interest on the debt worth 81 million Egyptian pounds that Isma'il had run up, the khedive was supportive of Gordon's plans for reform, but unable to do very much as he lacked the money to pay his civil servants and soldiers in Egypt, much less in the Sudan.[93]

Gordon travelled north to Cairo to meet with Baring and suggest the solution that Egypt suspend its interest payments for several years to allow Isma'il to pay the arrears owed to his soldiers and civil servants, arguing that once the Egyptian government was stabilised, then Egypt could start paying its debts without fear of causing a revolution.[93] Faught wrote that Gordon's plans were "farsighted and humane", but Baring had no interest in Gordon's plans to suspend the interest payments.[94] Gordon disliked Baring, writing he had "a pretentious, grand, patronizing way around him. We had a few words together ... When oil mixes with water, we will mix together".[94]

Gordon's attempts to end the slave trade faced resistance, most notably Rahama Zobeir, known as the "King of the Slavers" as he was the richest and most powerful of all the slave traders in the Sudan. An insurrection had broken out in Darfur province led by associates of Zobeir and Gordon went to deal with it. On 2 September 1877, Gordon clad in the full gold-braided ceremonial blue uniform of the Governor-General of the Sudan and wearing the tarboush (the type of fez reserved for a pasha), accompanied by an interpreter and a few bashi-bazouks, rode unannounced into the enemy camp to discuss the situation.[95] Gordon was met by Suleiman Zobeir, the son of Rahama Zobeir, and demanded, in the name of the Khedive of Egypt, that the rebels end their rebellion and accept the authority of their lord and master, telling Zobeir that he would "disarm and break them" if the rebellion did not end at once.[96] Gordon also promised that those rebels who laid down their arms would not be punished and would all be given jobs in the administration.[73]

One chief then pledged his loyalty to the Khedive, including Suleiman Zobeir himself, though the remainder retreated to the south.[73] Gordon visited the provinces of Berber and Dongola, and then returned to the Abyssinian frontier, before ending up back in Khartoum in January 1878. Gordon was summoned to Cairo, and arrived in March to be appointed president of a commission. The Khedive Isma'il was deposed in 1879 in favour of his son, Tewfik, by the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II following heavy diplomatic pressure from the British, French and Italian governments after Isma'il had quarrelled with Baring.[97]

Gordon returned south and proceeded to Harar, south of Abyssinia, and, finding the administration in poor standing, dismissed the governor. In 1878, Gordon fired the governor of Equatoria for corruption and replaced him with his former chief medical officer from his time in Equatoria, Dr. Emin Pasha, who had earned Gordon's respect. Gordon then returned to Khartoum, and went again into Darfur to suppress the slave traders. His subordinate, Gessi Pasha, fought with great success in the Bahr-el-Ghazal district in putting an end to the revolt there. In July 1878, Suleiman Zobeir had rebelled again, leading Gordon and his close friend Gessi to take to the field.[98]

In March 1879, Gessi had inflicted a sharp defeat on Zobeir even before Gordon had joined him to pursue their old enemy.[98] After several months of chasing Zobeir, Gessi and Gordon met at the village of Shaka in June 1879 when it was agreed that Gessi would continue the hunt while Gordon would return to Khartoum.[99] On 15 July 1879, Gessi finally captured Suleiman Zobeir together with 250 of his men and executed them.[100]

Gordon then tried another peace mission to Abyssinia. The matter ended with Gordon's imprisonment and transfer to Massawa. He returned to Cairo and resigned his Sudan appointment. He had gone to the Sudan with hope that he could reform the system.[64] According to Urabn, almost all of Gordon's reforms failed owing to the bureaucracy of the system which remained slow, corrupt, and oppressive.[64] At the end of his Governor-Generalship of the Sudan, Gordon had to admit that he had been a failure, an experience of defeat that so shattered him that he had a nervous breakdown. As Gordon travelled via Egypt to take the steamer back to Britain, a man who met him in Cairo described him as a broken man who was "rather off his head".[64] Before Gordon boarded the ship at Alexandria that was to take him home, he sent off a series of long telegrams to various ministers in London full of Biblical verse and quotations that he said offered the solution to all of the problems of modern life.[64] After Gordon resigned, Muhammad Rauf Pasha succeeded him as governor general of Sudan.[101]

In March 1880, Gordon recovered for a couple of weeks in the Hotel du Faucon in Lausanne, 3 Rue St Pierre, famous for its views on Lake Geneva and because several celebrities had stayed there, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, one of Gordon's heroes,[102] and possibly one of the reasons Gordon had chosen this hotel. In the hotel's restaurant, now a pub called Happy Days, he met another guest from Britain, the reverend R. H. Barnes, vicar of Heavitree near Exeter, who became a good friend. After Gordon's death, Barnes co-authored Charles George Gordon: A Sketch (1885),[103] which begins with the meeting at the hotel in Lausanne. The Reverend Reginald Barnes, who knew him well, describes him as "of the middle height, very strongly built".[104]

On 2 March 1880, on his way from London to Switzerland, Gordon had visited King Leopold II of Belgium in Brussels and was invited to take charge of the Congo Free State. Leopold tried very hard to convince Gordon to enter his service, not least because Gordon was known to be modest in his salary demands, unlike Leopold's current agent in the Congo, Henry Morton Stanley, who received a monthly salary of 300,000 Belgian francs.[105]

Gordon rejected Leopold's offers, partly because he was still emotionally attached to the Sudan and partly because he disliked the idea of working for Leopold's Congo Association, which was a private company owned by the King.[105] In April, the government of the Cape Colony offered him the position of commandant of the Cape local forces, which Gordon declined.[106] A deeply depressed Gordon wrote in his letter declining the offer that he knew, for reasons that he refused to explain, that he had only ten years left to live, and he wanted to do something great and grand in his last ten years.[106]

In May, the Marquess of Ripon, who had been given the post of Governor-General of India, asked Gordon to go with him as private secretary. Gordon accepted the offer, but shortly after arriving in India, he resigned. In the words of the American historian Immanuel C. Y. Hsu, Gordon was a "man of action" unsuited to a bureaucratic job.[107] Gordon found the life of a private secretary to be, in his words, a "living crucifixion" that was unbearably boring, leading him to resign with the intention of going to East Africa, particularly Zanzibar, to suppress the slave trade.[107]

Hardly had Gordon resigned when he was invited to Beijing by Sir Robert Hart, inspector-general of customs in China, saying his services were urgently needed in China as Russia and China were on the verge of war. Gordon was nostalgic for China, and knowing of the Sino-Russian crisis, he saw a chance to do something significant.[108] The British diplomat Thomas Francis Wade reported, "The Chinese government still holds Gordon Pasha in high regard", and were anxious to have him back to fight against Russia if war should break out.[109]

An exchange of telegrams ensued between the War Office in London and Gordon in Bombay about just what exactly he was planning on doing in China, and when Gordon replied that he would find out when he got there, he was ordered to stay.[11] He disobeyed orders and left on the first ship to China, an action that very much angered the Army's commander, the Duke of Cambridge.[110] Gordon arrived in Shanghai in July and met Li Hongzhang, and learned that there was risk of war with Russia. After meeting his old friend, Gordon assured Li that if Russia should attack he would resign his commission in the British Army to take up a commission in the Chinese Army, an action that if taken, risked prosecution under the Foreign Enlistments Act.[111]

Gordon informed the Foreign Office that he was willing to renounce his British citizenship and take Chinese citizenship as he would not abandon Li and his other Chinese friends should a Sino-Russian war begin. Gordon's willingness to renounce his British citizenship in order to fight with China in the event of war did much to raise his prestige in China.[112]

Gordon went to Beijing and used all his influence to ensure peace. He clashed repeatedly with Prince Chun, the leader of the war party in Beijing, who rejected Gordon's advice to seek a compromise solution as Gordon warned that the powerful Russian naval squadron in the Yellow Sea would allow the Russians to land at Tianjin and advance on Beijing.[113] At one point during a meeting with the Council of Ministers, an enraged Gordon picked up a Chinese–English dictionary, looked up the word idiocy, and then pointed at the equivalent Chinese word 白痴 with one hand while pointing at the ministers with the other.[113]

Gordon further advised the Qing court that it was unwise for the Manchu elite to live apart from and treat the Han Chinese majority as something less than human, warning that this not only weakened China in the present, but would cause a revolution in the future.[114] After speaking so bluntly, Gordon was ordered out of the court in Beijing, but was allowed to stay at Tianjin.[115] After meeting with him there, Hart described Gordon as "very eccentric" and "spending hours in prayer", writing that: "As much I like and respect him, I must say he is 'not all there'. Whether religion or vanity, or the softening of the brain — I don't know, but he seems to be alternatively arrogant and slavish, vain and humble, in his senses and out of them. It's a great pity!" Wade echoed Hart, writing that Gordon had changed since his last time in China, and was now "unbalanced", being utterly convinced that all of his ideas came from God, making him dangerously unreasonable since he now believed that everything he did was the will of God.[115]

Gordon was ordered home by London as the Foreign Office was not comfortable with the idea of him commanding the Chinese Army against Russia if war should break out, believing that this would cause an Anglo-Russian war and Gordon was told that he would be dishonourably discharged if he remained in China.[116] Although the Qing court rejected Gordon's advice to seek a compromise with Russia in the summer of 1880, Gordon's assessment of China's military backwardness and his stark warnings that the Russians would win if a war did break out played an important role in ultimately strengthening the peace party at the court and preventing war.[117]

Gordon returned to Britain and rented a flat on 8 Victoria Grove in London. In October 1880, he paid a two-week visit to Ireland, landing at Cork and travelling over much of the island. Gordon was sickened by the poverty of the Irish farmers, which led him to write a six-page memo to the Prime Minister, William Gladstone, urging land reforms in Ireland.[118][119] Gordon wrote: "The peasantry of the Northwest and Southwest of Ireland are much worse off than any of the inhabitants of Bulgaria, Asia Minor, China, India, or the Sudan".[120] Having been to all of those places and thus speaking with some authority, Gordon announced the "scandal" of poverty in Ireland could only be ended if the government were to buy the land from the Ascendency families, as the Anglo-Irish elite was known, and give it to their poor Irish tenant farmers.[120]

Gordon compared his plans for rural reform in Ireland to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833, and ended his letter with the assertion that if this were done, the unity of the United Kingdom would be preserved as the Irish would appreciate this great act of justice and the Irish independence movement would cease to exist as "they would have nothing more to seek from agitation".[120] Besides championing land reform in Ireland, Gordon spent the winter of 1880–81 in London socialising with his family and his few friends, such as Florence Nightingale and Alfred Tennyson.[120]

Gordon caricatured by Ape in Vanity Fair in 1881.

In April 1881, Gordon left for Mauritius as Commander, Royal Engineers. He remained in Mauritius until March 1882. The American historian John Semple Galbraith described Gordon as suffering from "utter boredom" during his time there.[121] Gordon saw his work in building forts to protect Mauritius from a possible Russian naval attack as pointless, and his main achievement during his time there was to advise the Crown to turn the Seychelles islands, whose beauty had greatly moved Gordon, into a new crown colony as Gordon argued it was impossible to govern the Seychelles from Port Louis.[120]

In a memo to London, Gordon warned against over-reliance on the Suez Canal, where the Russians could easily sink one ship to block the entire canal, thus leading Gordon to advise upon improving the Cape route to India with Britain developing a series of bases in Africa and in the Indian Ocean. Gordon visited the Seychelles in the summer of 1881 and decided the islands were the location of the Garden of Eden.[120] On the island of Praslin in the Valle de Mai, Gordon believed that he found the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the form of a coco de mer tree which fruit bore a close resemblance to a woman's body.[122] Gordon was promoted to major-general on 23 March 1882.[123]

Being unemployed, Gordon decided to go to Palestine, which at the time was part of the Ottoman vilayet of Syria,[124] a region he had long desired to visit, where he would remain for a year (1882–83). During his "career break" in the Holy Land, the very religious Gordon sought to explore his faith and biblical sites.[125]

In Jerusalem, Gordon lived with an American lawyer, Horatio Spafford, and his wife, Anna Spafford, who were the leaders of the American Colony in the Holy City.[126] The Spaffords had lost their home and much of their fortune in the Great Chicago Fire and then had seen one of their sons die of scarlet fever, four of their daughters drowned in a shipwreck, followed by the death of another son from scarlet fever, causing them to turn to religion as consolation for unbearable tragedy, making them very congenial company for Gordon during his stay in Jerusalem.[126] After his visit, Gordon suggested in his book Reflections in Palestine[127] a different location for Golgotha, the site of Christ's crucifixion. The site lies north of the traditional site at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and is now known as "The Garden Tomb", or sometimes as "Gordon's Calvary".[128] Gordon's interest was prompted by his religious beliefs, as he had become an evangelical Christian in 1854.[129]

King Leopold II then asked Gordon again to take charge of the Congo Free State.[130] He accepted and returned to London to make preparations, but soon after his arrival, the British requested that he proceed immediately to the Sudan, where the situation had deteriorated badly after his departure — another revolt had arisen, led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Mohammed Ahmed. The Mahdi is a messianic figure in Islam which tradition holds will appear at the dawn of every new (Islamic) century to strike down the enemies of Islam.[131]

The year 1881 was the Islamic year 1298, and to mark the coming of the new century, Ahmed announced that he was the Mahdi, and proclaimed a jihad against the Egyptian state. The long exploitation of the Sudan by Egypt led many Sudanese to rally to the Mahdi's black banner as he promised to expel the Egyptians, whom Ahmed denounced as apostates, and he announced he would establish an Islamic fundamentalist state marking a return to the "pure Islam" said to have been practised in the days of the Prophet Mohamed in Arabia.[131]

Additionally, Baring's policy of raising taxes to pay off the debts Isma'il had run up sparked much resentment in both Egypt and the Sudan.[132] In 1882, nationalist rage in Egypt against Baring's economic policies led to the revolt by Colonel Urabi Pasha, which was put down by Anglo-Egyptian troops. From September 1882 onwards, Egypt was a de facto British protectorate effectively ruled by Baring, though in theory, Egypt remained an Ottoman province with a very wide degree of autonomy until 1914. With Egypt under British rule, the British also inherited the problems of Egypt's colony, the Sudan, which the Egyptians were losing control of to the Mahdi.[133]

Mission to Khartoum

[edit]

Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi.

The Egyptian forces in the Sudan were insufficient to cope with the rebels, and the northern government was occupied with the suppression of the Urabi Revolt. By September 1882, the Egyptian position in the Sudan had grown perilous. In September 1883, an Egyptian Army force under Colonel William Hicks set out to destroy the Mahdi. The Egyptian soldiers were miserable fallāḥīn conscripts who had no interest in being in the Sudan, much less in fighting the Mahdi, and morale was so poor that Hicks had to chain his men together to prevent them from deserting.[134]

On 3–5 November 1883, the Ansar (whom the British called "Dervishes"), as the Mahdi's followers were known, destroyed the Egyptian army of 8,000 under Colonel Hicks at El Obeid, with only about 250 Egyptians surviving and Hicks being one of the slain.[134] The Ansar captured a large number of Remington rifles and ammunition cases together with many Krupp artillery guns and their shells.[125] After the Battle of El Obeid, Egyptian morale, never high to begin with, simply collapsed, and the black flag of the Mahdi soon flew over many towns in the Sudan.[134] By the end of 1883, the Egyptians held only the ports on the Red Sea and a narrow belt of land around the Nile in northern Sudan. In both cases, naval power was the key factor, as gunboats in the Red Sea and on the Nile provided a degree of firepower with which the Ansar could not cope.[135]

The only other place to hold out for a time was a region in the south held by the Governor of Equatoria, Emin Pasha. Following the destruction of Hicks's army, the Liberal Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, decided that the Sudan was not worth the trouble it would take to keep, and that the region should be abandoned to the Mahdi. In December 1883, the British government ordered Egypt to abandon the Sudan, but that was difficult to carry out, as it involved the withdrawal of thousands of Egyptian soldiers, civilian employees, and their families.[136]

At the beginning of 1884, Gordon had no interest in the Sudan and had just been hired to work as an officer with the newly-established Congo Free State. Gordon — despite or rather, because of his war hero status — disliked publicity and tried to avoid the press when he was in Britain.[135] While staying with his sister in Southampton, Gordon received an unexpected visitor, namely William Thomas Stead, the editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, to whom Gordon reluctantly agreed to give an interview.[137] Gordon wanted to talk about the Congo, but Stead kept on pressing him to talk about the Sudan. Finally, after much prompting on Stead's part, Gordon opened up and attacked Gladstone's Sudan policy, coming out for an intervention to defeat the Mahdi.[138] Gordon offered up a 19th-century anticipation of the domino theory, claiming:

The danger arises from the influence which the spectacle of a conquering Mahometan Power established close to your frontiers will exercise upon the population which you govern. In all the cities of Egypt, it will be felt that what the Mahdi has done, they may do; and, as he has driven out the intruder, they may do the same.[139]

Stead published his interview on 9 January 1884, on the front page of the Pall Mall Gazette alongside an editorial of his titled, "Chinese Gordon for the Sudan".[139] Urban wrote: "With this leader, William Stead's real motive in going to Southampton revealed itself at last. As to who tipped him off that the general would be staying here for just a couple of nights, we can only speculate".[140]

Stead's interview caused a media sensation and led to a popular clamour for Gordon to be sent to the Sudan.[141] Urban wrote: "The Pall Mall Gazette articles, in short, began a new chapter in international relations; powerful men using media manipulation of public opinion to trigger war. It is often suggested that that campaign by William Randolph Hearst's paper that led to the US invasion of Cuba in 1898 was the world's first episode of this kind, but the British press deserves these dubious laurels for its actions a full fourteen years earlier".[141] The man behind the campaign was the Adjutant General, Sir Garnet Wolseley—a skilled media manipulator who often leaked information to the press to effect changes in policy—and who was strongly opposed to Gladstone's policy of pulling out of the Sudan.[142]

In 1880, the Liberals had won the general election on a platform of overseas retrenchment, and Gladstone had put his principles into practice by withdrawing from the Transvaal and Afghanistan in 1881. There was a secret "ultra" faction in the War Office led by Wolseley that felt that the Liberal government was too inclined to withdraw from various places all over the globe at the first sign of trouble, and who were determined to sabotage the withdrawal from the Sudan.[143] Gordon and Wolseley were good friends (Wolseley being one of the people Gordon prayed for every night), and after a meeting with Wolseley at the War Office to discuss the crisis in the Sudan, Gordon left convinced that he had to go to the Sudan to "carry out the work of God".[134]

With public opinion demanding that Gordon be sent to the Sudan, on 16 January 1884, the Gladstone government decided to send him there, albeit with the very limited mandate to report on the situation and advise on the best means of carrying out the evacuation.[144] Gladstone had gone to his estate at Hawarden to recover from illness and thus was not present at the meeting on 18 January where Gordon was given the Sudan command, but he was under the impression that Gordon's mission was advisory, whereas the four ministers present at the meeting had given Gordon the impression that his mission was executive in nature.[145]

Gladstone felt that this was a deft political move. Public opinion would be satisfied with "Chinese Gordon" going to the Sudan, but at the same time, Gordon was given such a limited mandate that the evacuation would proceed as planned. The Cabinet felt highly uncomfortable with the appointment, as they had been pressured by the press to send a man who was opposed to their Sudan policy to take command there. The Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville, wondered if they had just committed a "gigantic folly".[146] Gordon made a short trip to Brussels to tell King Leopold that he would not be going to the Congo after all, news that enraged the King.[11]

General Gordon in Khartoum.

The British government asked Gordon to go to Khartoum to report on the best method of carrying out the evacuation. Gordon started for Cairo in January 1884, accompanied by Lt. Col. J. D. H. Stewart. At Cairo, he received further instructions from Sir Evelyn Baring, and was appointed Governor-General with executive powers by the Khedive Tewfik Pasha, who also gave Gordon an edict ordering him to establish a government in the Sudan. This Gordon would later use as a reason for staying in Khartoum.[147] Baring disapproved of sending Gordon to the Sudan, writing in a report to London that: "A man who habitually consults the Prophet Isaiah when he is in a difficulty is not apt to obey the orders of anyone".[148] Gordon immediately confirmed Baring's fears as he started to issue press statements attacking the rebels as "a feeble lot of stinking Dervishes" and demanded he be allowed to "smash up the Mahdi".[149] Gordon sent a telegram to Khartoum reading: "Don't be panic-stricken. Ye are men, not women. I am coming. Gordon".[147]

Urban wrote that Gordon's "most stupid mistake" occurred when he revealed his secret orders at a meeting of tribal leaders on 12 February at Berber, explaining that the Egyptians were pulling out, leading to almost all of the Arab tribes of northern Sudan declaring their loyalty to the Mahdi. Given that Gordon himself in his interview with Stead had stated: "The moment it is known that we have given up the game, every man will go over to the Mahdi", his decision to reveal that the Egyptians were pulling out remains inexplicable.[149] Shortly afterwards, Gordon wrote what Urban called a "bizarre" letter to the Mahdi telling him to accept the authority of the Khedive of Egypt and offered him the chance to work as one of Gordon's provincial governors. The Mahdi contemptuously rejected Gordon's offer and sent back a letter demanding Gordon convert to Islam.[149]

The Mahdi ended his letter with the remark: "I am the Expected Mahdi and I do not boast! I am the successor of God's Prophet and I have no need of any sultanate of Kordofan or anywhere else!"[150] Even Wolseley had cause to regret sending Gordon, as the general revealed himself to be a loose cannon whose press statements attacking the Liberal government were "obstructing rather than furthering his plans to take over the Sudan".[149] Travelling through Korosko and Berber, he arrived at Khartoum on 18 February, where he offered his earlier foe, the slaver-king Rahama Zobeir, release from prison in exchange for leading troops against Ahmed.[151]

Gordon's abrupt mood swings and contradictory advice confirmed the Cabinet's view of him as mercurial and unstable.[11] Even an observer as sympathetic as Winston Churchill wrote about Gordon: "Mercury uncontrolled by the force of gravity was not on several occasions more unstable than Charles Gordon. His moods were capricious and uncertain, his passions violent, his impulses sudden and inconsistent. The mortal enemy of the morning had become a trusted ally by night".[152]

The novelist John Buchan wrote that Gordon was so "unlike other men that he readily acquired a spiritual ascendency over all who knew him well and many who did not", but at the same time, Gordon had a "dualism", in that "the impression of single-heartedness was an illusion, for all his life his soul was the stage of conflict".[152] Gordon's attempt to have his former archenemy Zobeir—the "King of the Slavers" whom he had hunted for years and whose son he had executed—installed as the new Sultan of the Sudan appalled Gladstone and offended his former admirers in the Anti-Slavery Society.[147]

Preparing the defence of Khartoum

[edit]

The maximum extent of the Mahdist State from 1881 to 1898, with national boundaries as of 2000 displayed.

After arriving in Khartoum, Gordon announced that on the grounds of honour, he would not evacuate Khartoum, but rather, would hold the city against the Mahdi.[147] Gordon was well-received by a crowd of about 9,000 during his return to Khartoum where the crowd continually chanted, "Father!" and "Sultan!" Gordon assured the people of Khartoum in a speech delivered in his rough-hewn Arabic that the Mahdi was coming with his Army of Islam marching under their black banners, but to have no fear as here he would be stopped.[150] Gordon had a garrison of about 8,000 soldiers armed with Remington rifles, together with a colossal ammunition dump containing millions of rounds.[153]

Gordon commenced the task of sending the women, the children, the sick, and the wounded to Egypt. About 2,500 people had been removed before the Mahdi's forces closed in on Khartoum. Gordon hoped to have the influential local leader, Sebehr Rahma, appointed to take control of Sudan, but the British government refused to support a former slaver. During this time in Khartoum, Gordon befriended Irish journalist Frank Powers, The Times (London) correspondent in the Sudan. Powers was delighted that the charismatic Gordon had no anti-Catholic prejudices and treated him as an equal.[154] The hero-worshiping Powers wrote about Gordon: "He is indeed I believe the greatest man of this century". Gordon granted Powers privileged access and in return, Powers started to write a series of popular articles for The Times depicting Gordon as the solitary hero taking on a vast horde of fanatical Muslims.[154]

Gordon made all of his personal dispatches to London public (there was no Official Secrets Act at the time) in attempts to win public opinion over to his policy, writing on one dispatch: "Not secret as far as I am concerned".[155] At one point, Gordon suggested in a telegram to Gladstone that the notoriously corrupt Ottoman Sultan Abdul-Hamid II could be bribed into sending 3,000 Ottoman troops for the relief of Khartoum and if the British government was unwilling and/or unable to pay that amount, he was certain that either Pope Leo XIII or a group of American millionaires would be.[156]

The advance of the rebels against Khartoum was combined with a revolt in the eastern Sudan. Colonel Valentine Baker led an Egyptian force out of Suakin and was badly defeated by 1,000 Haddendowa warriors who declared their loyalty to the Mahdi under Osman Digna at Al-Teb with 2,225 Egyptian soldiers and 96 officers killed.[71] Because the Egyptian troops at Suakin were repeatedly defeated, a British force was sent to Suakin under General Sir Gerald Graham, which drove the rebels away in several hard-fought actions. At Tamai on 13 March 1884, Graham was attacked by the Haddendowa (whom the British nicknamed "Fuzzy Wuzzies") whom he defeated, but in the course of the battle, the Haddendowa broke a Black Watch square, an action later celebrated in the Kipling poem "Fuzzy-Wuzzy".[157]

The ferocity of the Haddendowa attacks astonished the British, and Graham argued that he needed more troops if he were to advance deeper into the Sudan while one newspaper correspondent reported that the average British soldiers did not understand why they were in the Sudan fighting "such brave fellows" for "the sake of the wretched Egyptians".[155] Gordon urged that the road from Suakin to Berber be opened, but his request was refused by the government in London, and in April Graham and his forces were withdrawn and Gordon and the Sudan were abandoned. The garrison at Berber surrendered in May, and Khartoum was completely isolated.[158]

Gordon decided to stay and hold Khartoum despite the orders of the Gladstone government to merely report about the best means of supervising the evacuation of the Sudan.[147] Powers, who acted as Gordon's unofficial press attaché, wrote in The Times: "We are daily expecting British troops. We cannot bring ourselves to believe that we are to be abandoned".[159] In his diary, Gordon wrote: "I own to having been very insubordinate to Her Majesty's Government and its officials, but it is my nature, and I cannot help it. I fear I have not even tried to play battledore and shuttlecock with them. I know if I was chief I would never employ myself for I am incorrigible".[147]

Due to public opinion, the government dared not sack Gordon, but the Cabinet was extremely angry about Gordon's insubordination, with many privately saying if Gordon wanted to defy orders by holding Khartoum, then he only deserved what he was going to get. Gladstone himself took Gordon's attacks on his Sudan policy very personally.[159] One Cabinet minister wrote: "The London newspapers and the Tories clamor for an expedition to Khartoum, the former from ignorance, the latter because it is the best model of embarrassing us ... Of course it is not an impossible undertaking, but it is melancholy to think of the waste of lives and the treasure which it must involve".[159] The Cabinet itself was divided and confused about just what to do about the Sudan crisis, leading to a highly dysfunctional style of decision-making.[11]

[![10 piastre promissory note issued and hand-signed by Gen. Gordon during the Siege of Khartoum (26 April 1884)[160]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/SUD-S103a-Siege_of_Khartoum-10_Piastres_%281884%29.jpg/228px-SUD-S103a-Siege_of_Khartoum-10_Piastres_%281884%29.jpg) ](/wiki/File:SUD-S103a-Siege%5Fof%5FKhartoum-10%5FPiastres%5F%281884%29.jpg)

](/wiki/File:SUD-S103a-Siege%5Fof%5FKhartoum-10%5FPiastres%5F%281884%29.jpg)

Gordon had a strong death wish, and clearly wanted to die fighting at Khartoum, writing in a letter to his sister: "I feel so very much inclined to wish it His will might be my release. Earth's joys grow very dim, its glories have faded". In his biography of Gordon, Anthony Nutting wrote that Gordon was obsessed with "the ever-present, constantly repeated desire for martyrdom and for that glorious immortality in union with God and away from the wretchedness of life on this earth".[147]