DNA microarray (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Collection of microscopic DNA spots attached to a solid surface

How to use a microarray for genotyping. The video shows the process of extracting genotypes from a human spit sample using microarrays. Genotyping is a major use of DNA microarrays, but with some modifications they can also be used for other purposes such as measurement of gene expression and epigenetic markers.

A DNA microarray (also commonly known as DNA chip or biochip) is a collection of microscopic DNA spots attached to a solid surface. Scientists use DNA microarrays to measure the expression levels of large numbers of genes simultaneously or to genotype multiple regions of a genome. Each DNA spot contains picomoles (10−12 moles) of a specific DNA sequence, known as probes (or reporters or oligos). These can be a short section of a gene or other DNA element that are used to hybridize a cDNA or cRNA (also called anti-sense RNA) sample (called target) under high-stringency conditions. Probe-target hybridization is usually detected and quantified by detection of fluorophore-, silver-, or chemiluminescence-labeled targets to determine relative abundance of nucleic acid sequences in the target. The original nucleic acid arrays were macro arrays approximately 9 cm × 12 cm and the first computerized image based analysis was published in 1981.[1] It was invented by Patrick O. Brown. An example of its application is in SNPs arrays for polymorphisms in cardiovascular diseases, cancer, pathogens and GWAS analysis. It is also used for the identification of structural variations and the measurement of gene expression.

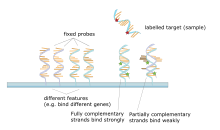

Hybridization of the target to the probe

Further information: § A typical protocol

The core principle behind microarrays is hybridization between two DNA strands, the property of complementary nucleic acid sequences to specifically pair with each other by forming hydrogen bonds between complementary nucleotide base pairs. A high number of complementary base pairs in a nucleotide sequence means tighter non-covalent bonding between the two strands. After washing off non-specific bonding sequences, only strongly paired strands will remain hybridized. Fluorescently labeled target sequences that bind to a probe sequence generate a signal that depends on the hybridization conditions (such as temperature), and washing after hybridization. Total strength of the signal, from a spot (feature), depends upon the amount of target sample binding to the probes present on that spot. Microarrays use relative quantitation in which the intensity of a feature is compared to the intensity of the same feature under a different condition, and the identity of the feature is known by its position.

The steps required in a microarray experiment

Two Affymetrix chips. A match is shown at bottom left for size comparison.

Many types of arrays exist and the broadest distinction is whether they are spatially arranged on a surface or on coded beads:

- The traditional solid-phase array is a collection of orderly microscopic "spots", called features, each with thousands of identical and specific probes attached to a solid surface, such as glass, plastic or silicon biochip (commonly known as a genome chip, DNA chip or gene array). Thousands of these features can be placed in known locations on a single DNA microarray.

- The alternative bead array is a collection of microscopic polystyrene beads, each with a specific probe and a ratio of two or more dyes, which do not interfere with the fluorescent dyes used on the target sequence.

DNA microarrays can be used to detect DNA (as in comparative genomic hybridization), or detect RNA (most commonly as cDNA after reverse transcription) that may or may not be translated into proteins. The process of measuring gene expression via cDNA is called expression analysis or expression profiling.

Applications include:

| Application or technology | Synopsis |

|---|---|

| Gene expression profiling | In an mRNA or gene expression profiling experiment the expression levels of thousands of genes are simultaneously monitored to study the effects of certain treatments, diseases, and developmental stages on gene expression. For example, microarray-based gene expression profiling can be used to identify genes whose expression is changed in response to pathogens or other organisms by comparing gene expression in infected to that in uninfected cells or tissues.[2] |

| Comparative genomic hybridization | Assessing genome content in different cells or closely related organisms, as originally described by Patrick Brown, Jonathan Pollack, Ash Alizadeh and colleagues at Stanford.[3][4] |

| GeneID | Small microarrays to check IDs of organisms in food and feed (like GMO [1]), mycoplasms in cell culture, or pathogens for disease detection, mostly combining PCR and microarray technology. |

| Chromatin immunoprecipitation on Chip | DNA sequences bound to a particular protein can be isolated by immunoprecipitating that protein (ChIP), these fragments can be then hybridized to a microarray (such as a tiling array) allowing the determination of protein binding site occupancy throughout the genome. Example protein to immunoprecipitate are histone modifications (H3K27me3, H3K4me2, H3K9me3, etc.), Polycomb-group protein (PRC2:Suz12, PRC1:YY1) and trithorax-group protein (Ash1) to study the epigenetic landscape or RNA polymerase II to study the transcription landscape. |

| DamID | Analogously to ChIP, genomic regions bound by a protein of interest can be isolated and used to probe a microarray to determine binding site occupancy. Unlike ChIP, DamID does not require antibodies but makes use of adenine methylation near the protein's binding sites to selectively amplify those regions, introduced by expressing minute amounts of protein of interest fused to bacterial DNA adenine methyltransferase. |

| SNP detection | Identifying single nucleotide polymorphism among alleles within or between populations.[5] Several applications of microarrays make use of SNP detection, including genotyping, forensic analysis, measuring predisposition to disease, identifying drug-candidates, evaluating germline mutations in individuals or somatic mutations in cancers, assessing loss of heterozygosity, or genetic linkage analysis. |

| Alternative splicing detection | An exon junction array design uses probes specific to the expected or potential splice sites of predicted exons for a gene. It is of intermediate density, or coverage, to a typical gene expression array (with 1–3 probes per gene) and a genomic tiling array (with hundreds or thousands of probes per gene). It is used to assay the expression of alternative splice forms of a gene. Exon arrays have a different design, employing probes designed to detect each individual exon for known or predicted genes, and can be used for detecting different splicing isoforms. |

| Fusion genes microarray | A fusion gene microarray can detect fusion transcripts, e.g. from cancer specimens. The principle behind this is building on the alternative splicing microarrays. The oligo design strategy enables combined measurements of chimeric transcript junctions with exon-wise measurements of individual fusion partners. |

| Tiling array | Genome tiling arrays consist of overlapping probes designed to densely represent a genomic region of interest, sometimes as large as an entire human chromosome. The purpose is to empirically detect expression of transcripts or alternatively spliced forms which may not have been previously known or predicted. |

| Double-stranded B-DNA microarrays | Right-handed double-stranded B-DNA microarrays can be used to characterize novel drugs and biologicals that can be employed to bind specific regions of immobilized, intact, double-stranded DNA. This approach can be used to inhibit gene expression.[6][7] They also allow for characterization of their structure under different environmental conditions. |

| Double-stranded Z-DNA microarrays | Left-handed double-stranded Z-DNA microarrays can be used to identify short sequences of the alternative Z-DNA structure located within longer stretches of right-handed B-DNA genes (e.g., transcriptional enhancement, recombination, RNA editing).[6][7] The microarrays also allow for characterization of their structure under different environmental conditions. |

| Multi-stranded DNA microarrays (triplex-DNA microarrays and quadruplex-DNA microarrays) | Multi-stranded DNA and RNA microarrays can be used to identify novel drugs that bind to these multi-stranded nucleic acid sequences. This approach can be used to discover new drugs and biologicals that have the ability to inhibit gene expression.[6][7][8][9] These microarrays also allow for characterization of their structure under different environmental conditions. |

Specialised arrays tailored to particular crops are becoming increasingly popular in molecular breeding applications. In the future they could be used to screen seedlings at early stages to lower the number of unneeded seedlings tried out in breeding operations.[10]

Microarrays can be manufactured in different ways, depending on the number of probes under examination, costs, customization requirements, and the type of scientific question being asked. Arrays from commercial vendors may have as few as 10 probes or as many as 5 million or more micrometre-scale probes.

Spotted vs. in situ synthesised arrays

[edit]

A DNA microarray being printed by a robot at the University of Delaware

Microarrays can be fabricated using a variety of technologies, including printing with fine-pointed pins onto glass slides, photolithography using pre-made masks, photolithography using dynamic micromirror devices, ink-jet printing,[11][12] or electrochemistry on microelectrode arrays.

In spotted microarrays, the probes are oligonucleotides, cDNA or small fragments of PCR products that correspond to mRNAs. The probes are synthesized prior to deposition on the array surface and are then "spotted" onto glass. A common approach utilizes an array of fine pins or needles controlled by a robotic arm that is dipped into wells containing DNA probes and then depositing each probe at designated locations on the array surface. The resulting "grid" of probes represents the nucleic acid profiles of the prepared probes and is ready to receive complementary cDNA or cRNA "targets" derived from experimental or clinical samples. This technique is used by research scientists around the world to produce "in-house" printed microarrays in their own labs. These arrays may be easily customized for each experiment, because researchers can choose the probes and printing locations on the arrays, synthesize the probes in their own lab (or collaborating facility), and spot the arrays. They can then generate their own labeled samples for hybridization, hybridize the samples to the array, and finally scan the arrays with their own equipment. This provides a relatively low-cost microarray that may be customized for each study, and avoids the costs of purchasing often more expensive commercial arrays that may represent vast numbers of genes that are not of interest to the investigator. Publications exist which indicate in-house spotted microarrays may not provide the same level of sensitivity compared to commercial oligonucleotide arrays,[13] possibly owing to the small batch sizes and reduced printing efficiencies when compared to industrial manufactures of oligo arrays.

In oligonucleotide microarrays, the probes are short sequences designed to match parts of the sequence of known or predicted open reading frames. Although oligonucleotide probes are often used in "spotted" microarrays, the term "oligonucleotide array" most often refers to a specific technique of manufacturing. Oligonucleotide arrays are produced by printing short oligonucleotide sequences designed to represent a single gene or family of gene splice-variants by synthesizing this sequence directly onto the array surface instead of depositing intact sequences. Sequences may be longer (60-mer probes such as the Agilent design) or shorter (25-mer probes produced by Affymetrix) depending on the desired purpose; longer probes are more specific to individual target genes, shorter probes may be spotted in higher density across the array and are cheaper to manufacture. One technique used to produce oligonucleotide arrays include photolithographic synthesis (Affymetrix) on a silica substrate where light and light-sensitive masking agents are used to "build" a sequence one nucleotide at a time across the entire array.[14] Each applicable probe is selectively "unmasked" prior to bathing the array in a solution of a single nucleotide, then a masking reaction takes place and the next set of probes are unmasked in preparation for a different nucleotide exposure. After many repetitions, the sequences of every probe become fully constructed. More recently, Maskless Array Synthesis from NimbleGen Systems has combined flexibility with large numbers of probes.[15]

Two-channel vs. one-channel detection

[edit]

Diagram of typical dual-colour microarray experiment

Two-color microarrays or two-channel microarrays are typically hybridized with cDNA prepared from two samples to be compared (e.g. diseased tissue versus healthy tissue) and that are labeled with two different fluorophores.[16] Fluorescent dyes commonly used for cDNA labeling include Cy3, which has a fluorescence emission wavelength of 570 nm (corresponding to the green part of the light spectrum), and Cy5 with a fluorescence emission wavelength of 670 nm (corresponding to the red part of the light spectrum). The two Cy-labeled cDNA samples are mixed and hybridized to a single microarray that is then scanned in a microarray scanner to visualize fluorescence of the two fluorophores after excitation with a laser beam of a defined wavelength. Relative intensities of each fluorophore may then be used in ratio-based analysis to identify up-regulated and down-regulated genes.[17]

Oligonucleotide microarrays often carry control probes designed to hybridize with RNA spike-ins. The degree of hybridization between the spike-ins and the control probes is used to normalize the hybridization measurements for the target probes. Although absolute levels of gene expression may be determined in the two-color array in rare instances, the relative differences in expression among different spots within a sample and between samples is the preferred method of data analysis for the two-color system. Examples of providers for such microarrays includes Agilent with their Dual-Mode platform, Eppendorf with their DualChip platform for colorimetric Silverquant labeling, and TeleChem International with Arrayit.

In single-channel microarrays or one-color microarrays, the arrays provide intensity data for each probe or probe set indicating a relative level of hybridization with the labeled target. However, they do not truly indicate abundance levels of a gene but rather relative abundance when compared to other samples or conditions when processed in the same experiment. Each RNA molecule encounters protocol and batch-specific bias during amplification, labeling, and hybridization phases of the experiment making comparisons between genes for the same microarray uninformative. The comparison of two conditions for the same gene requires two separate single-dye hybridizations. Several popular single-channel systems are the Affymetrix "Gene Chip", Illumina "Bead Chip", Agilent single-channel arrays, the Applied Microarrays "CodeLink" arrays, and the Eppendorf "DualChip & Silverquant". One strength of the single-dye system lies in the fact that an aberrant sample cannot affect the raw data derived from other samples, because each array chip is exposed to only one sample (as opposed to a two-color system in which a single low-quality sample may drastically impinge on overall data precision even if the other sample was of high quality). Another benefit is that data are more easily compared to arrays from different experiments as long as batch effects have been accounted for.

One channel microarray may be the only choice in some situations. Suppose i {\displaystyle i}

| number of samples | one-channel microarray | two channel microarray | two channel microarray (with reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

i {\displaystyle i}  |

i {\displaystyle i}  |

i ( i − 1 ) / 2 {\displaystyle i(i-1)/2}  |

i − 1 {\displaystyle i-1}  |

Examples of levels of application of microarrays. Within the organisms, genes are transcribed and spliced to produce mature mRNA transcripts (red). The mRNA is extracted from the organism and reverse transcriptase is used to copy the mRNA into stable ds-cDNA (blue). In microarrays, the ds-cDNA is fragmented and fluorescently labelled (orange). The labelled fragments bind to an ordered array of complementary oligonucleotides, and measurement of fluorescent intensity across the array indicates the abundance of a predetermined set of sequences. These sequences are typically specifically chosen to report on genes of interest within the organism's genome.[18]

This is an example of a DNA microarray experiment which includes details for a particular case to better explain DNA microarray experiments, while listing modifications for RNA or other alternative experiments.

- The two samples to be compared (pairwise comparison) are grown/acquired. In this example treated sample (case) and untreated sample (control).

- The nucleic acid of interest is purified: this can be RNA for expression profiling, DNA for comparative hybridization, or DNA/RNA bound to a particular protein which is immunoprecipitated (ChIP-on-chip) for epigenetic or regulation studies. In this example total RNA is isolated (both nuclear and cytoplasmic) by guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction (e.g. Trizol) which isolates most RNA (whereas column methods have a cut off of 200 nucleotides) and if done correctly has a better purity.

- The purified RNA is analysed for quality (by capillary electrophoresis) and quantity (for example, by using a NanoDrop or NanoPhotometer spectrometer). If the material is of acceptable quality and sufficient quantity is present (e.g., >1μg, although the required amount varies by microarray platform), the experiment can proceed.

- The labeled product is generated via reverse transcription and followed by an optional PCR amplification. The RNA is reverse transcribed with either polyT primers (which amplify only mRNA) or random primers (which amplify all RNA, most of which is rRNA). miRNA microarrays ligate an oligonucleotide to the purified small RNA (isolated with a fractionator), which is then reverse transcribed and amplified.

- The label is added either during the reverse transcription step, or following amplification if it is performed. The sense labeling is dependent on the microarray; e.g. if the label is added with the RT mix, the cDNA is antisense and the microarray probe is sense, except in the case of negative controls.

- The label is typically fluorescent; only one machine uses radiolabels.

- The labeling can be direct (not used) or indirect (requires a coupling stage). For two-channel arrays, the coupling stage occurs before hybridization, using aminoallyl uridine triphosphate (aminoallyl-UTP, or aaUTP) and NHS amino-reactive dyes (such as cyanine dyes); for single-channel arrays, the coupling stage occurs after hybridization, using biotin and labeled streptavidin. The modified nucleotides (usually in a ratio of 1 aaUTP: 4 TTP (thymidine triphosphate)) are added enzymatically in a low ratio to normal nucleotides, typically resulting in 1 every 60 bases. The aaDNA is then purified with a column (using a phosphate buffer solution, as Tris contains amine groups). The aminoallyl group is an amine group on a long linker attached to the nucleobase, which reacts with a reactive dye.

* A form of replicate known as a dye flip can be performed to control for dye artifacts in two-channel experiments; for a dye flip, a second slide is used, with the labels swapped (the sample that was labeled with Cy3 in the first slide is labeled with Cy5, and vice versa). In this example, aminoallyl-UTP is present in the reverse-transcribed mixture.

- The labeled samples are then mixed with a proprietary hybridization solution which can consist of SDS, SSC, dextran sulfate, a blocking agent (such as Cot-1 DNA, salmon sperm DNA, calf thymus DNA, PolyA, or PolyT), Denhardt's solution, or formamine.

- The mixture is denatured and added to the pinholes of the microarray. The holes are sealed and the microarray hybridized, either in a hyb oven, where the microarray is mixed by rotation, or in a mixer, where the microarray is mixed by alternating pressure at the pinholes.

- After an overnight hybridization, all nonspecific binding is washed off (SDS and SSC).

- The microarray is dried and scanned by a machine that uses a laser to excite the dye and measures the emission levels with a detector.

- The image is gridded with a template and the intensities of each feature (composed of several pixels) is quantified.

- The raw data is normalized; the simplest normalization method is to subtract background intensity and scale so that the total intensities of the features of the two channels are equal, or to use the intensity of a reference gene to calculate the t-value for all of the intensities. More sophisticated methods include z-ratio, loess and lowess regression and RMA (robust multichip analysis) for Affymetrix chips (single-channel, silicon chip, in situ synthesized short oligonucleotides).

Microarrays and bioinformatics

[edit]

Gene expression values from microarray experiments can be represented as heat maps to visualize the result of data analysis.

The advent of inexpensive microarray experiments created several specific bioinformatics challenges:[19] the multiple levels of replication in experimental design (Experimental design); the number of platforms and independent groups and data format (Standardization); the statistical treatment of the data (Data analysis); mapping each probe to the mRNA transcript that it measures (Annotation); the sheer volume of data and the ability to share it (Data warehousing).

Experimental design

[edit]

Due to the biological complexity of gene expression, the considerations of experimental design that are discussed in the expression profiling article are of critical importance if statistically and biologically valid conclusions are to be drawn from the data.

There are three main elements to consider when designing a microarray experiment. First, replication of the biological samples is essential for drawing conclusions from the experiment. Second, technical replicates (e.g. two RNA samples obtained from each experimental unit) may help to quantitate precision. The biological replicates include independent RNA extractions. Technical replicates may be two aliquots of the same extraction. Third, spots of each cDNA clone or oligonucleotide are present as replicates (at least duplicates) on the microarray slide, to provide a measure of technical precision in each hybridization. It is critical that information about the sample preparation and handling is discussed, in order to help identify the independent units in the experiment and to avoid inflated estimates of statistical significance.[20]

Microarray data is difficult to exchange due to the lack of standardization in platform fabrication, assay protocols, and analysis methods. This presents an interoperability problem in bioinformatics. Various grass-roots open-source projects are trying to ease the exchange and analysis of data produced with non-proprietary chips:

For example, the "Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment" (MIAME) checklist helps define the level of detail that should exist and is being adopted by many journals as a requirement for the submission of papers incorporating microarray results. But MIAME does not describe the format for the information, so while many formats can support the MIAME requirements, as of 2007[update] no format permits verification of complete semantic compliance. The "MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) Project" is being conducted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop standards and quality control metrics which will eventually allow the use of MicroArray data in drug discovery, clinical practice and regulatory decision-making.[21] The MGED Society has developed standards for the representation of gene expression experiment results and relevant annotations.

National Center for Toxicological Research scientist reviews microarray data.

Microarray data sets are commonly very large, and analytical precision is influenced by a number of variables. Statistical challenges include taking into account effects of background noise and appropriate normalization of the data. Normalization methods may be suited to specific platforms and, in the case of commercial platforms, the analysis may be proprietary.[22] Algorithms that affect statistical analysis include:

- Image analysis: gridding, spot recognition of the scanned image (segmentation algorithm), removal or marking of poor-quality and low-intensity features (called flagging).

- Data processing: background subtraction (based on global or local background), determination of spot intensities and intensity ratios, visualisation of data (e.g. see MA plot), and log-transformation of ratios, global or local normalization of intensity ratios, and segmentation into different copy number regions using step detection algorithms.[23]

- Class discovery analysis: This analytic approach, sometimes called unsupervised classification or knowledge discovery, tries to identify whether microarrays (objects, patients, mice, etc.) or genes cluster together in groups. Identifying naturally existing groups of objects (microarrays or genes) which cluster together can enable the discovery of new groups that otherwise were not previously known to exist. During knowledge discovery analysis, various unsupervised classification techniques can be employed with DNA microarray data to identify novel clusters (classes) of arrays.[24] This type of approach is not hypothesis-driven, but rather is based on iterative pattern recognition or statistical learning methods to find an "optimal" number of clusters in the data. Examples of unsupervised analyses methods include self-organizing maps, neural gas, k-means cluster analyses,[25] hierarchical cluster analysis, Genomic Signal Processing based clustering and model-based cluster analysis. For some of these methods the user also has to define a distance measure between pairs of objects. Although the Pearson correlation coefficient is usually employed, several other measures have been proposed and evaluated in the literature.[26] The input data used in class discovery analyses are commonly based on lists of genes having high informativeness (low noise) based on low values of the coefficient of variation or high values of Shannon entropy, etc. The determination of the most likely or optimal number of clusters obtained from an unsupervised analysis is called cluster validity. Some commonly used metrics for cluster validity are the silhouette index, Davies-Bouldin index,[27] Dunn's index, or Hubert's Γ {\displaystyle \Gamma }

statistic.

- Class prediction analysis: This approach, called supervised classification, establishes the basis for developing a predictive model into which future unknown test objects can be input in order to predict the most likely class membership of the test objects. Supervised analysis[24] for class prediction involves use of techniques such as linear regression, k-nearest neighbor, learning vector quantization, decision tree analysis, random forests, naive Bayes, logistic regression, kernel regression, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, mixture of experts, and supervised neural gas. In addition, various metaheuristic methods are employed, such as genetic algorithms, covariance matrix self-adaptation, particle swarm optimization, and ant colony optimization. Input data for class prediction are usually based on filtered lists of genes which are predictive of class, determined using classical hypothesis tests (next section), Gini diversity index, or information gain (entropy).

- Hypothesis-driven statistical analysis: Identification of statistically significant changes in gene expression are commonly identified using the t-test, ANOVA, Bayesian method[28] Mann–Whitney test methods tailored to microarray data sets, which take into account multiple comparisons[29] or cluster analysis.[30] These methods assess statistical power based on the variation present in the data and the number of experimental replicates, and can help minimize type I and type II errors in the analyses.[31]

- Dimensional reduction: Analysts often reduce the number of dimensions (genes) prior to data analysis.[24] This may involve linear approaches such as principal components analysis (PCA), or non-linear manifold learning (distance metric learning) using kernel PCA, diffusion maps, Laplacian eigenmaps, local linear embedding, locally preserving projections, and Sammon's mapping.

- Network-based methods: Statistical methods that take the underlying structure of gene networks into account, representing either associative or causative interactions or dependencies among gene products.[32] Weighted gene co-expression network analysis is widely used for identifying co-expression modules and intramodular hub genes. Modules may corresponds to cell types or pathways. Highly connected intramodular hubs best represent their respective modules.

Microarray data may require further processing aimed at reducing the dimensionality of the data to aid comprehension and more focused analysis.[33] Other methods permit analysis of data consisting of a low number of biological or technical replicates; for example, the Local Pooled Error (LPE) test pools standard deviations of genes with similar expression levels in an effort to compensate for insufficient replication.[34]

The relation between a probe and the mRNA that it is expected to detect is not trivial.[35] Some mRNAs may cross-hybridize probes in the array that are supposed to detect another mRNA. In addition, mRNAs may experience amplification bias that is sequence or molecule-specific. Thirdly, probes that are designed to detect the mRNA of a particular gene may be relying on genomic EST information that is incorrectly associated with that gene.

Microarray data was found to be more useful when compared to other similar datasets. The sheer volume of data, specialized formats (such as MIAME), and curation efforts associated with the datasets require specialized databases to store the data. A number of open-source data warehousing solutions, such as InterMine and BioMart, have been created for the specific purpose of integrating diverse biological datasets, and also support analysis.

Alternative technologies

[edit]

Advances in massively parallel sequencing has led to the development of RNA-Seq technology, that enables a whole transcriptome shotgun approach to characterize and quantify gene expression.[36][37] Unlike microarrays, which need a reference genome and transcriptome to be available before the microarray itself can be designed, RNA-Seq can also be used for new model organisms whose genome has not been sequenced yet.[37]

An array or slide is a collection of features spatially arranged in a two dimensional grid, arranged in columns and rows.

Block or subarray: a group of spots, typically made in one print round; several subarrays/ blocks form an array.

Case/control: an experimental design paradigm especially suited to the two-colour array system, in which a condition chosen as control (such as healthy tissue or state) is compared to an altered condition (such as a diseased tissue or state).

Channel: the fluorescence output recorded in the scanner for an individual fluorophore and can even be ultraviolet.

Dye flip or dye swap or fluor reversal: reciprocal labelling of DNA targets with the two dyes to account for dye bias in experiments.

Scanner: an instrument used to detect and quantify the intensity of fluorescence of spots on a microarray slide, by selectively exciting fluorophores with a laser and measuring the fluorescence with a filter (optics) photomultiplier system.

Spot or feature: a small area on an array slide that contains picomoles of specific DNA samples.

For other relevant terms see:

Cyanine dyes, such as Cy3 and Cy5, are commonly used fluorophores with microarrays

- ^ Taub, Floyd (1983). "Laboratory methods: Sequential comparative hybridizations analyzed by computerized image processing can identify and quantitate regulated RNAs". DNA. 2 (4): 309–327. doi:10.1089/dna.1983.2.309. PMID 6198132.

- ^ Adomas A; Heller G; Olson A; Osborne J; Karlsson M; Nahalkova J; Van Zyl L; Sederoff R; Stenlid J; Finlay R; Asiegbu FO (2008). "Comparative analysis of transcript abundance in Pinus sylvestris after challenge with a saprotrophic, pathogenic or mutualistic fungus". Tree Physiol. 28 (6): 885–897. doi:10.1093/treephys/28.6.885. PMID 18381269.

- ^ Pollack JR; Perou CM; Alizadeh AA; Eisen MB; Pergamenschikov A; Williams CF; Jeffrey SS; Botstein D; Brown PO (1999). "Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays". Nat Genet. 23 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1038/12640. PMID 10471496. S2CID 997032.

- ^ Moran G; Stokes C; Thewes S; Hube B; Coleman DC; Sullivan D (2004). "Comparative genomics using Candida albicans DNA microarrays reveals absence and divergence of virulence-associated genes in Candida dubliniensis". Microbiology. 150 (Pt 10): 3363–3382. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27221-0. hdl:2262/6097. PMID 15470115.

- ^ Hacia JG; Fan JB; Ryder O; Jin L; Edgemon K; Ghandour G; Mayer RA; Sun B; Hsie L; Robbins CM; Brody LC; Wang D; Lander ES; Lipshutz R; Fodor SP; Collins FS (1999). "Determination of ancestral alleles for human single-nucleotide polymorphisms using high-density oligonucleotide arrays". Nat Genet. 22 (2): 164–167. doi:10.1038/9674. PMID 10369258. S2CID 41718227.

- ^ a b c Gagna, Claude E.; Lambert, W. Clark (1 May 2009). "Novel multistranded, alternative, plasmid and helical transitional DNA and RNA microarrays: implications for therapeutics". Pharmacogenomics. 10 (5): 895–914. doi:10.2217/pgs.09.27. ISSN 1744-8042. PMID 19450135.

- ^ a b c Gagna, Claude E.; Clark Lambert, W. (1 March 2007). "Cell biology, chemogenomics and chemoproteomics – application to drug discovery". Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2 (3): 381–401. doi:10.1517/17460441.2.3.381. ISSN 1746-0441. PMID 23484648. S2CID 41959328.

- ^ Mukherjee, Anirban; Vasquez, Karen M. (1 August 2011). "Triplex technology in studies of DNA damage, DNA repair, and mutagenesis". Biochimie. 93 (8): 1197–1208. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2011.04.001. ISSN 1638-6183. PMC 3545518. PMID 21501652.

- ^ Rhodes, Daniela; Lipps, Hans J. (15 October 2015). "G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology". Nucleic Acids Research. 43 (18): 8627–8637. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv862. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 4605312. PMID 26350216.

- ^ Rasheed, Awais; Hao, Yuanfeng; Xia, Xianchun; Khan, Awais; Xu, Yunbi; Varshney, Rajeev K.; He, Zhonghu (2017). "Crop Breeding Chips and Genotyping Platforms: Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives" (PDF). Molecular Plant. 10 (8). Chin Acad Sci+Chin Soc Plant Bio+Shanghai Inst Bio Sci (Elsevier): 1047–1064. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2017.06.008. ISSN 1674-2052. PMID 28669791. S2CID 33780984.

- ^ J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2000 Mar 16;42(3):105–10. DNA-printing: utilization of a standard inkjet printer for the transfer of nucleic acids to solid supports. Goldmann T, Gonzalez JS.

- ^ Lausted C; et al. (2004). "POSaM: a fast, flexible, open-source, inkjet oligonucleotide synthesizer and microarrayer". Genome Biology. 5 (8): R58. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-8-r58. PMC 507883. PMID 15287980.

- ^ Bammler T, Beyer RP; Consortium, Members of the Toxicogenomics Research; Kerr, X; Jing, LX; Lapidus, S; Lasarev, DA; Paules, RS; Li, JL; Phillips, SO (2005). "Standardizing global gene expression analysis between laboratories and across platforms". Nat Methods. 2 (5): 351–356. doi:10.1038/nmeth754. PMID 15846362. S2CID 195368323.

- ^ Pease AC; Solas D; Sullivan EJ; Cronin MT; Holmes CP; Fodor SP (1994). "Light-generated oligonucleotide arrays for rapid DNA sequence analysis". PNAS. 91 (11): 5022–5026. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.5022P. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.11.5022. PMC 43922. PMID 8197176.

- ^ Nuwaysir EF; Huang W; Albert TJ; Singh J; Nuwaysir K; Pitas A; Richmond T; Gorski T; Berg JP; Ballin J; McCormick M; Norton J; Pollock T; Sumwalt T; Butcher L; Porter D; Molla M; Hall C; Blattner F; Sussman MR; Wallace RL; Cerrina F; Green RD (2002). "Gene Expression Analysis Using Oligonucleotide Arrays Produced by Maskless Photolithography". Genome Res. 12 (11): 1749–1755. doi:10.1101/gr.362402. PMC 187555. PMID 12421762.

- ^ Shalon D; Smith SJ; Brown PO (1996). "A DNA microarray system for analyzing complex DNA samples using two-color fluorescent probe hybridization". Genome Res. 6 (7): 639–645. doi:10.1101/gr.6.7.639. PMID 8796352.

- ^ Tang T; François N; Glatigny A; Agier N; Mucchielli MH; Aggerbeck L; Delacroix H (2007). "Expression ratio evaluation in two-colour microarray experiments is significantly improved by correcting image misalignment". Bioinformatics. 23 (20): 2686–2691. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm399. PMID 17698492.

- ^ Shafee, Thomas; Lowe, Rohan (2017). "Eukaryotic and prokaryotic gene structure". WikiJournal of Medicine. 4 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2017.002. ISSN 2002-4436. S2CID 35766676.

- ^ Tinker, Anna V.; Boussioutas, Alex; Bowtell, David D.L. (2006). "The challenges of gene expression microarrays for the study of human cancer". Cancer Cell. 9 (5): 333–339. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.001. ISSN 1535-6108. PMID 16697954.

- ^ Churchill, GA (2002). "Fundamentals of experimental design for cDNA microarrays" (PDF). Nature Genetics. supplement. 32: 490–5. doi:10.1038/ng1031. PMID 12454643. S2CID 15412245. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ NCTR Center for Toxicoinformatics – MAQC Project

- ^ "Prosigna | Prosigna algorithm". prosigna.com. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Little, M.A.; Jones, N.S. (2011). "Generalized Methods and Solvers for Piecewise Constant Signals: Part I" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 467 (2135): 3088–3114. doi:10.1098/rspa.2010.0671. PMC 3191861. PMID 22003312.

- ^ a b c Peterson, Leif E. (2013). Classification Analysis of DNA Microarrays. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-17081-6.

- ^ De Souto M et al. (2008) Clustering cancer gene expression data: a comparative study, BMC Bioinformatics, 9(497).

- ^ Jaskowiak, Pablo A; Campello, Ricardo JGB; Costa, Ivan G (2014). "On the selection of appropriate distances for gene expression data clustering". BMC Bioinformatics. 15 (Suppl 2): S2. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-15-S2-S2. PMC 4072854. PMID 24564555.

- ^ Bolshakova N, Azuaje F (2003) Cluster validation techniques for genome expression data, Signal Processing, Vol. 83, pp. 825–833.

- ^ Ben Gal, I.; Shani, A.; Gohr, A.; Grau, J.; Arviv, S.; Shmilovici, A.; Posch, S.; Grosse, I. (2005). "Identification of transcription factor binding sites with variable-order Bayesian networks". Bioinformatics. 21 (11): 2657–2666. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti410. ISSN 1367-4803. PMID 15797905.

- ^ Yuk Fai Leung and Duccio Cavalieri, Fundamentals of cDNA microarray data analysis. Trends in Genetics Vol.19 No.11 November 2003.

- ^ Priness I.; Maimon O.; Ben-Gal I. (2007). "Evaluation of gene-expression clustering via mutual information distance measure". BMC Bioinformatics. 8 (1): 111. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-111. PMC 1858704. PMID 17397530.

- ^ Wei C; Li J; Bumgarner RE (2004). "Sample size for detecting differentially expressed genes in microarray experiments". BMC Genomics. 5: 87. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-5-87. PMC 533874. PMID 15533245.

- ^ Emmert-Streib, F. & Dehmer, M. (2008). Analysis of Microarray Data A Network-Based Approach. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31822-3.

- ^ Wouters L; Gõhlmann HW; Bijnens L; Kass SU; Molenberghs G; Lewi PJ (2003). "Graphical exploration of gene expression data: a comparative study of three multivariate methods". Biometrics. 59 (4): 1131–1139. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.730.3670. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341X.2003.00130.x. PMID 14969494. S2CID 16248921.

- ^ Jain N; Thatte J; Braciale T; Ley K; O'Connell M; Lee JK (2003). "Local-pooled-error test for identifying differentially expressed genes with a small number of replicated microarrays". Bioinformatics. 19 (15): 1945–1951. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg264. PMID 14555628.

- ^ Barbosa-Morais, N. L.; Dunning, M. J.; Samarajiwa, S. A.; Darot, J. F. J.; Ritchie, M. E.; Lynch, A. G.; Tavare, S. (18 November 2009). "A re-annotation pipeline for Illumina BeadArrays: improving the interpretation of gene expression data". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (3): e17. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp942. PMC 2817484. PMID 19923232.

- ^ Mortazavi, Ali; Brian A Williams; Kenneth McCue; Lorian Schaeffer; Barbara Wold (July 2008). "Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq". Nat Methods. 5 (7): 621–628. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1226. ISSN 1548-7091. PMID 18516045. S2CID 205418589.

- ^ a b Wang, Zhong; Mark Gerstein; Michael Snyder (January 2009). "RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics". Nat Rev Genet. 10 (1): 57–63. doi:10.1038/nrg2484. ISSN 1471-0056. PMC 2949280. PMID 19015660.

- Microarray Animation 1Lec.com

- PLoS Biology Primer: Microarray Analysis

- Rundown of microarray technology

- ArrayMining.net – a free web-server for online microarray analysis

- Microarray – How does it work?

- PNAS Commentary: Discovery of Principles of Nature from Mathematical Modeling of DNA Microarray Data

- DNA microarray virtual experiment