Donald McKay (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

American shipbuilder

| Donald McKay | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 4, 1810 (1810-09-04)Jordan Falls, Shelburne County, Colony of Nova Scotia |

| Died | September 20, 1880(1880-09-20) (aged 70)Hamilton, Massachusetts, USA |

| Occupation | Ship Designer |

| Known for | Flying Cloud |

| Spouse(s) | Albenia Boole (married 1833–1848, until her death) and Mary Cressy Litchfield (m.1850) |

Donald McKay (September 4, 1810 – September 20, 1880) was a Nova Scotian-born American designer and builder of sailing ships, famed for his record-setting extreme clippers.

McKay was born in Jordan Falls, Shelburne County, on Nova Scotia's South Shore, the oldest son and one of eighteen children of Hugh McKay, a fisherman and a farmer, and Ann McPherson McKay. Both of his parents were of Scottish descent. He was named after his grandfather, Captain Donald McKay, a British officer, who after the Revolutionary war moved to Nova Scotia from the Scottish Highlands.[1]

Early years as a shipbuilder

[edit]

In 1826 McKay moved to New York, where he served his apprenticeship under Isaac Webb in the Webb & Allen shipyard from 1827 to 1831.[1][2] He then returned briefly to Nova Scotia and built a boat with his uncle, but after they were swindled from the proceeds he returned to New York and took a job in the Brown & Bell shipyard, working for Jacob Bell.[3] In 1840, following a recommendation from Bell, he was taken on as a supervisor at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but stayed only briefly because of the anti-immigrant sentiment towards him (as a Canadian) from the men he was supervising.[3] Bell came to the rescue and found him an assignment to work on a packet ship in a shipyard in Wiscasset, Maine. Returning south when that assignment was complete, he stopped in Newburyport and took a job as a foreman in the yard of John Currier, Jr.,[4] where he supervised the construction of the 427-ton Delia Walker. Currier was very impressed with McKay and offered him a five-year contract, which McKay refused driven by desire to own his own business.[5]

In 1841, William Currier (no relation to John) offered McKay the chance to become a partner in what would become the Currier & McKay shipyard in Newburyport. Two years later, with McKay now designing ships on his own, he and Currier parted ways and McKay went into business with a man named William Picket, building the packet ships St. George and John R. Skiddy. The partnership with Picket was "pleasant and profitable", but after McKay built the Joshua Bates for Enoch Train's new packet line to Liverpool in 1844, Train persuaded him to move to East Boston and start his own shipyard there.[3][5] Train not only provided the financing for McKay to do this but then became his biggest customer, commissioning seven more packet ships and four clipper ships between 1845 and 1853—including the legendary extreme clipper Flying Cloud.[3]

Ships built before 1845

[edit]

- 1840 Delia Walker, 427 tons, McKay finished her for John Currier, Jr.

- 1841 Mary Broughton, 323 tons, barque, built by Currier & McKay.

- 1842 Ashburton, 449 tons, ship, build by Currier & McKay.

- 1842 Rio Trader Courier, early clipper trading ship, 380 tons OM was the first ship fully designed and built by Donald McKay himself, as a partner in the firm of Currier & McKay, on a commission from Andrew Foster & Son, New York. She was built at Newburyport, Massachusetts. At the time it was rather unusual for a such advanced vessel to be built outside of New York or Baltimore. She was employed in the Rio coffee trade and made a big deal of money to her owners, but most importantly brought a much needed fame to McKay.[7]

- 1843 St. George, 845 tons, pioneer packet of Red Cross Line, built by McKay & Picket.

- 1844 John R. Skiddy, 930 tons, packet, built by McKay & Picket.

- 1844 Joshua Bates, 620 tons, pioneer packet of Enoch Train's White Diamond Line. The White Diamond Line was one of the most important Atlantic emigrant routes from Europe to North America at the time. Built by McKay & Pickett.

East Boston shipyard

[edit]

McKay Shipyard, East Boston, c. 1855

In 1845 McKay, as a sole owner, established his own shipyard on Border Street, East Boston, where he built some of the finest American ships over a career of almost 25 years.

One of his first large orders was building five large packet ships for Enoch Train's White Diamond line between 1845 and 1850: Washington Irving, Anglo Saxon, Anglo American, Daniel Webster, and Ocean Monarch.[8] The Ocean Monarch was lost to fire on August 28, 1848, soon after leaving Liverpool and within sight of Wales; over 170 of the passengers and crew perished.[9] The Washington Irving carried Patrick Kennedy, grandfather of Kennedy family patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., to Boston in 1849.

In the summer of 1851, McKay visited Liverpool and secured a contract to build four large ships for James Baines & Co.'s Australian trade: Lightning (1854), Champion of the Seas (1854), James Baines (1854), and Donald McKay (1855).[10]

Ships built after 1845

[edit]

- 1845 Washington Irving, 751 tons, Boston-Liverpool packet ship, built for Enoch Train's White Diamond Line. Launched 15 September 1845. Sold to England in 1852.

- 1846 Anglo-Saxon, 894 tons, 147 ft long, built for Enoch Train, Launched 5 September 1846.

- 1846 New World, 1404 tons, packet ship, sold in 1882 to Austrians and renamed Rudolph Kaiser. Her painting is available at Royal Museums Greenwich.[13][14]

- 1847 Ocean Monarch, 1301 tons OM, built for Enoch Train.

- 1847 A.Z., 700 tons, packet for Zerega&Co of New York.

- 1847 Anglo-American, 704 tons, packet ship built for Enoch Train.[15]

- 1848 Jenny Lind, 533 tons, packet ship.

- 1848 L.Z., 897 tons, packet for Zerega&Co of New York.

- 1849 Plymouth Rock, 960 tons, packet ship.

- 1849 Helicon, extreme clipper barque, 400 tons OM

- 1849 Reindeer, extreme clipper trading ship, 800 tons OM, built in East Boston

- 1849 Parliament, 998 tons, packet ship.

- 1850 Moses Wheeler, extreme clipper trading ship, 900 tons OM, built for Wheeler & King, Boston.

- 1850 Sultana, extreme clipper barque, 400 tons OM

- 1850 Cornelius Grinell, 118 tons, packet ship

- 1850 Antarctic, 1116 tons, packet for Zerega&Co of New York

- 1850 Daniel Webster, 1187 tons, built for Enoch Train.

- 1850 Stag Hound, extreme clipper, 1534 tons OM – first large clipper ship built by Donald McKay

- 1851 Flying Cloud, extreme clipper, 1782 tons OM

- 1851 Staffordshire, extreme clipper, 1817 tons OM. She was launched at East Boston, Massachusetts, for Enoch Train & Co. She wrecked off Cape Sable, Nova Scotia, in 1853.

- 1851 North America, extreme clipper, 1464 tons OM

Sovereign of the Seas (1852) - 1851 Flying Fish, extreme clipper, 1505 tons OM. She was launched at East Boston, Massachusetts, for Messrs. Sampson & Tappan, Boston. She wrecked on the 23rd of November 1958 off Fuzhou, China en route to New York with a cargo of tea. The wreck was sold to a Manilla merchant. After she was rebuilt at Whampoa, China she was renamed the El Bueno Suceso.[16]

- 1852 Sovereign of the Seas, extreme clipper, 2421 tons OM. Known as the Enoch Train until the time she was launched, at which point she was purchased and renamed by Grinnell & Minturn.[3] At the time she was fastest sailing ship ever built.[17][18] She was wrecked in the Malacca Straits in 1859.

- 1852 Westward Ho!, extreme clipper, 1650 tons OM, burned in Callao in 1864.

- 1852 Bald Eagle, extreme clipper, 1704 tons OM

- 1853 Empress of the Seas, extreme clipper, 2200 tons OM, burned in Australia in 1881.

- 1853 Star of Empire, extreme clipper, 2050 tons OM, built for the Boston and Liverpool packet line of Enoch Train & Co. In 1857, laden with guano, she broke to pieces on Currituck Beach, N. C.[19][20]

- 1853 Chariot of Fame, extreme clipper, 2050 tons OM, 220 ft. She was launched at East Boston, Massachusetts, for Enoch Train & Co. Per Richard McKay sources, sold in 1862 and came to her end in January, 1876, being abandoned or lost at sea en route from Chincha Islands to Cork.[21]

Great Republic (1853) - 1853 Great Republic, extreme clipper barque, 4555 tons OM – largest clipper ship ever built

- 1853 Romance of the Sea, extreme clipper, 1782 tons OM. She was launched at East Boston, Massachusetts, for George B. Upton and employed in the California Trade. She disappeared en route to San Francisco after having left Hong Kong 31 December 1862.[22]

- 1854 Lightning, extreme clipper, 2083 tons OM, built for Messrs, Baines & Co. She burned while loading wool at Geelong, Australia on the 31st of October 1869.

- 1854 Champion of the Seas, extreme clipper, 2447 tons OM, built for Messrs, Baines & Co.

- 1854 James Baines, extreme clipper, 2525 tons OM, built for Messrs, Baines & Co.

- 1854 Blanche Moore, extreme clipper, 1787 tons OM

- 1854 Santa Claus, medium clipper, 1256 tons OM

- 1854 Benin, barque, 692 tons.

- 1854 Commodore Perry, medium clipper, 1964 tons OM, built for Black Ball Line, burned near Bombay on 27 August 1869.[23]

- 1854 Japan, medium clipper, 1964 tons OM, built for Messrs, Baines & Co.

- 1855 Donald McKay, extreme clipper, 2594 tons OM, 266 ft, built for Messrs, Baines & Co., last extreme clipper ship built by Donald McKay, burned and broken up in 1888.[24]

- 1855 Zephyr, medium clipper, 1184 tons OM

- 1855 Defender, medium clipper, 1413 tons OM

- 1856 Henry Hill, medium clipper barque, 568 tons OM

- 1856 Mastiff, medium clipper, 1030 tons OM. She was launched at East Boston, Massachusetts, for George B. Upton for the California and China trade. She was lost to a fire en route for the Sandwich Islands in the South Pacific on the 15th of September 1859. The entire crew and all passengers were rescued by the British ship HMS Achilles and brought to Honolulu.

- 1856 Minnehaha, medium clipper, 1695 tons OM

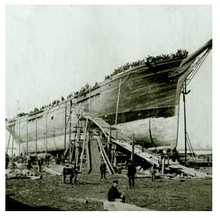

Glory of the Seas, ready to launch (1869)

- 1856 Amos Lawrence, medium clipper, 1396 tons OM

- 1856 Abbott Lawrence, medium clipper, 1497 tons OM

- 1856 Baltic, medium clipper, 1372 tons OM, 188 feet, built for Zerega&Co of New York.

- 1856 Adriatic, medium clipper, 1327 tons OM, built for Zerega&Co of New York. She ran aground, off Whale Cove, on Digby Neck Peninsula, Nova Scotia, Canada on the 24th December 1859.

- 1858 Alhambra, medium clipper, 1097 tons OM

- 1859 Benj. S. Wright, 107 tons.

- 1860 Mary B. Dyer, schooner.

- 1860 H. & R. Atwood, schooner.

- 1861–1862 General Putnam, ship.

- 1864–1865 Trefoil, wooden screw propeller ship, 370 tons.

- 1864–1865 Yucca, wooden screw propeller ship, 373 tons.

- 1864–1865 Nausett, iron clad monitor.

- 1864–1865 Ashuelot, iron side-wheel double ended ship, 1030 tons.

- 1866 Geo. B. Upton, wooden screw propeller ship, 604 tons.

- 1866 Theodore D. Wagner, wooden screw propeller ship, 607 tons.

- 1867 North Star, brig, 410 tons.

- 1867 Helen Morris, medium clipper, 1285 tons OM

- 1868 Sovereign of the Seas, 1502 tons

- 1868 R.R. Higgins, schooner, 96 tons.

- 1869 Glory of the Seas, medium clipper, 2102 tons OM. Last clipper designed by McKay. Scrapped for her metal at Brace Point, West Seattle on the 13th of May 1923. Her figurehead is preserved at the India House, New York.

- 1869 Frank Atwood, schooner, 107 tons.

- 1874–1875 Adams, sloop of war, 615 tons.

- 1874–1875 Essex, sloop of war.

- 1875 America, schooner yacht, originally built by William H. Brown in 1851, rebuilt by McKay in 1875. Namesake, and original champion, of the America's Cup.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Lightning set multiple records

- 436 miles in a 24-hour period in 1854

- 430 miles in 24 hours while bound for Australia

- 63 days and 3 hours from Melbourne, Australia, to Liverpool, England

- Sovereign of the Seas posted the fastest speed ever by a sailing ship – 22 kts. in 1854.

- Champion of the Seas set the record of 465 miles in 24 hours in December 1854; this record stood until 1984.[25]

- James Baines logged a speed of 21 knots (June 18, 1856)

- Flying Cloud made two 89-day passages New York to San Francisco[26]

- Bald Eagle set the record of 78 days 22 hours for a fully laden ship from San Francisco to New York.

In 1869, under financial pressure from previous losses, McKay sold his shipyard and worked for some time in other shipyards. He retired to his farm near Hamilton, Massachusetts, spending the rest of his life there. He died in 1880 in relative poverty and was buried in Newburyport.[1]

McKay's designs were characterized by a long fine bow with increasing hollow and waterlines. He was perhaps influenced by the writings of John W. Griffiths, designer of the China clipper Rainbow in 1845. The long hollow bow helped to penetrate rather than ride over the wave produced by the hull at high speeds, reducing resistance as hull speed is approached. Hull speed is the natural speed of a wave the same length as the ship, in knots, 1.34 × LWL {\displaystyle 1.34\times {\sqrt {\mbox{LWL}}}}

Pan Am named one of their Boeing 747s Clipper Donald McKay in his honor.

There is a monument to McKay in South Boston, near Fort Independence, overlooking the channel, that lists all his ships. There were more than thirty ships listed.

His house in East Boston was designated a Boston Landmark in 1977[27] and is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

A memorial pavilion to McKay, including a painting of his famous "Flying Cloud", can be found at Piers Park in East Boston.

McKay was inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame on November 9, 2019.[28]

- ^ a b c Chase, Mary Ellen. Donald McKay and the clipper ships. Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 931945646.

- ^ McCutchan, Philip Tall Ships The Golden Age of Sail London Book Club Associates 1976 p.37

- ^ a b c d e Miles, Vincent J. (2022). Transatlantic Train: The Untold Story of the Boston Merchant Who Launched Donald McKay to Fame. Dorchester, Massachusetts: Dorchester Historical Society. ISBN 979-8987314302.

- ^ Strong, Charles Stanley (1957). The story of American sailing ships. New York: Grosset and Dunlap. pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c d McKay, Richard C. (2011). Donald McKay and His Famous Sailing Ships. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486288208.

- ^ a b "Donald McKay Yard". www.bruzelius.info. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ Arthur H. Clark (1910). The Clipper Ship Era: An Epitome of Famous American and British, Clipper Ships, Their Owners, Builders, Commanders, and Crews. New York and London: The Knickerbocker Press.

- ^ Laxton, Edward The Famine Ships The Irish Exodus to America 1846–51 London Bloomsbury 1997 pp144–5 ISBN 0-7475-3500-0

- ^ Laxton, Edward op cit pp91–8

- ^ MacGregor, David R. (David Roy) (1988). Fast sailing ships : their design and construction, 1775–1875. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870218956. OCLC 17899628.

- ^ Census Reports Tenth Census: June 1, 1880, Volume 8, p.72

- ^ "Ships built by Donald McKay". www.uscommunityindex.com. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "United States Packet Ship New World 1404 tons register. Built at Boston, Mass. 1846 by Donald McKay". Europeana Collections. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "United States Packet Ship New World 1404 tons register. Built at Boston, Mass. 1846 by Donald McKay – National Maritime Museum". collections.rmg.co.uk. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "Ship Building in East Bsoton". Boston Evening Transcript (published as Daily Evening Transcript) (Boston, Massachusetts). January 1, 1848.

- ^ Edson, Merritt A.: _Flying Fish Yard Lengths._Nautical Research Journal Vol. 27, Bethesda, 1981. p 43.

- ^ "San Francisco Commerce, Past, Present and Future". Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine. April 1888. p. 370. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ LAING, ALEXANDER (1944). Clipper Ship Men. DUELL SLOAN & PEARCE INC. p. 18.

- ^ "Star of Empire". Richmond Dispatch. May 27, 1857. p. 1.

- ^ ""Star of Empire" Currituck". New-York Tribune. May 9, 1857. p. 8.

- ^ McKay, Richard (1928). Some Famous Sailing Ships and Their Builder Donald McKay. New York.

{{[cite book](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fbook "Template:Cite book")}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Octavius T. Howe; Frederick G. Matthews (1986). American Clipper Ships 1833–1858. Vol. 1. New York. ISBN 0-486-25115-2.

{{[cite book](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fbook "Template:Cite book")}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The New Packet Ship "Commodore Perry"".

- ^ McLean, Duncan: The New Clipper Donald McKay. The Boston Daily Atlas, Vol. XXIV, February 6, 1855

- ^ James S. Learmont (1957) Speed Under Sail, The Mariner's Mirror, 43:3, 225-231

- ^ Octavius T. Howe; Frederick G. Matthews (1986). American Clipper Ships 1833–1858. Vol. 1. New York. ISBN 0-486-25115-2.

{{[cite book](/wiki/Template:Cite%5Fbook "Template:Cite book")}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Public Hearing on Donald McKay House. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Landmarks Commission. 1977.

- ^ "Donald McKay, 2019 Inductee". Nshof.org. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Judson, Clara Ingram (1943). Donald McKay: Designer of Clipper Ships Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, p. 136, Url

- Images of Donald McKay's Shipyard – Museum of Science, Boston, MA

- Works by or about Donald McKay at the Internet Archive

- Donald MacKay Memorial, Jordan Falls, NS

- Model of Flying Cloud Clipper Ship, Smithsonian

- Figurehead from clipper ship Donald McKay, Mystic Seaport Museum

- List of ships built by Donald McKay

- 1850 McKay and the Clipper Age – .pdf case study in innovation, bostoninnovation.org

- Scientific American, "Donald McKay", 9 October 1880, p. 228