Lambertian reflectance (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Model for determining radiant energy reflected off diffuse surfaces

Diagram of Lambertian diffuse reflection. The black arrow shows incident radiance, and the red arrows show the reflected radiant intensity in each direction. When viewed from various angles, the reflected radiant intensity and the apparent area of the surface both vary with the cosine of the viewing angle, so the reflected radiance (intensity per unit area) is the same from all viewing angles.

Lambertian reflectance is the property that defines an ideal "matte" or diffusely reflecting surface. The apparent brightness of a Lambertian surface to an observer is the same regardless of the observer's angle of view.[1] More precisely, the reflected radiant intensity obeys Lambert's cosine law, which makes the reflected radiance the same in all directions. Lambertian reflectance is named after Johann Heinrich Lambert, who introduced the concept of perfect diffusion in his 1760 book Photometria.

Unfinished wood exhibits roughly Lambertian reflectance, but wood finished with a glossy coat of polyurethane does not, since the glossy coating creates specular highlights. Though not all rough surfaces are Lambertian, this is often a good approximation, and is frequently used when the characteristics of the surface are unknown.[2]

Spectralon is a material which is designed to exhibit an almost perfect Lambertian reflectance.[1]

Use in computer graphics

[edit]

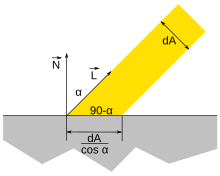

In computer graphics, Lambertian reflection is often used as a model for diffuse reflection. This technique causes all closed polygons (such as a triangle within a 3D mesh) to reflect light equally in all directions when rendered. The reflection decreases when the surface is tilted away from being perpendicular to the light source, however, because the area is illuminated by a smaller fraction of the incident radiation.[3]

The reflection is calculated by taking the dot product of the surface's unit normal vector, N {\displaystyle \mathbf {N} }

B D = L ⋅ N C I L {\displaystyle B_{D}=\mathbf {L} \cdot \mathbf {N} CI_{\text{L}}}

where B D {\displaystyle B_{D}}

L ⋅ N = | N | | L | cos α = cos α {\displaystyle \mathbf {L} \cdot \mathbf {N} =|N||L|\cos {\alpha }=\cos {\alpha }}

where α {\displaystyle \alpha }

Lambertian reflection from polished surfaces is typically accompanied by specular reflection (gloss), where the surface luminance is highest when the observer is situated at the perfect reflection direction (i.e. where the direction of the reflected light is a reflection of the direction of the incident light in the surface), and falls off sharply.

While Lambertian reflectance usually refers to the reflection of light by an object, it can be used to refer to the reflection of any wave. For example, in ultrasound imaging, "rough" tissues are said to exhibit Lambertian reflectance.[4]

- ^ a b Ikeuchi, Katsushi (2014). "Lambertian Reflectance". Encyclopedia of Computer Vision. Springer. pp. 441–443. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-31439-6_534. ISBN 978-0-387-30771-8. S2CID 11390799.

- ^ Lu, Renfu (2016). Light Scattering Technology for Food Property, Quality and Safety Assessment. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 9781482263350.

- ^ Angel, Edward (2003). Interactive Computer Graphics: A Top-Down Approach Using OpenGL (third ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-31252-5.

- ^ Keelan, Robert; Shimada, Kenji; Rabin, Yoed (2016-06-23). "GPU-Based Simulation of Ultrasound Imaging Artifacts for Cryosurgery Training". Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 16 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1177/1533034615623062. ISSN 1533-0346. PMC 5616109. PMID 26818026.