Liaoningvenator (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Extinct genus of dinosaurs

| _Liaoningvenator_Temporal range: Barremian, 126 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ | |

|---|---|

|

|

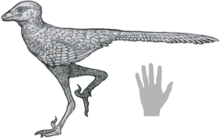

| Life reconstruction with hand for scale | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Troodontidae |

| Genus: | †_Liaoningvenator_Shen et al., 2017 |

| Type species | |

| †_Liaoningvenator curriei_Shen et al., 2017 |

Liaoningvenator (meaning "Liaoning hunter") is a genus of troodontid theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of China. It contains a single species, L. curriei, named after paleontologist Phillip J. Currie in 2017 by Shen Cai-Zhi and colleagues from an articulated, nearly complete skeleton, one of the most complete troodontid specimens known. Shen and colleagues found indicative traits that placed Liaoningvenator within the Troodontidae. These traits included its numerous, small, and closely packed teeth, as well as the vertebrae towards the end of its tail having shallow grooves in place of neural spines on their top surfaces.

Within the Troodontidae, the closest relative of Liaoningvenator was Eosinopteryx, and it was also closely related to Anchiornis and Xiaotingia; while these have traditionally been placed outside the Troodontidae, the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Shen and colleagues offered evidence supporting the alternative identification of these paravians as troodontids. Compared to its close relatives, however, Liaoningvenator had relatively long legs, in particular the femora. As the fifth troodontid known from geographically and temporally comparable strata, Liaoningvenator increases the diversity of Chinese troodontids.

With a total body length (estimated lengths of the skull, neck, trunk, and tail combined) of approximately 69 cm (27 in), Liaoningvenator is a small troodontid.[1]

Liaoningvenator possesses a long, narrow, and triangular skull that measured 9.8 cm (3.9 in) long. At the front of the snout, like Sinovenator and Xixiasaurus, the premaxilla excludes the maxilla from the rim of the nostril. There are three openings on the surface of the maxilla, the premaxillary, maxillary, and antorbital fenestrae. Below, the maxilla forms the secondary palate as in Byronosaurus, Gobivenator, and Xixiasaurus. Uniquely among troodontids, the postorbital bone is slender and radiates into three processes. Like Zanabazar, there is a pneumatic diverticulum in the jugal bone where an air sac was present within the bone; there is also a pneumatic opening on the rear side of the quadrate bone, as in other troodontids.[2] Unlike Sauronithoides, Zanabazar, and Stenonychosaurus, the crest separating the parietal bones does not participate in the border of the supratemporal (upper) temporal fenestra at the back of the skull.[1]

Characteristic of troodontids,[2] Liaoningvenator has a pitted groove on the outer edge of its shallow and triangular lower jaw. The bottom margin of the jaw is slightly convex; in Sinornithoides, it is straight. The dentary and angular bones may have formed a flexible joint within the jaw - that is, an intramandibular joint.[3] Unlike Xiaotingia, the dentary and maxilla terminate at the same position in the jaw. Also like other troodontids (with Sinusonasus being an exception), Liaoningvenator has a number of small, closely spaced teeth, with at least 15 in the upper jaw and 23 in the lower jaw. The teeth towards the rear of the lower jaw are serrated, unlike a number of basal troodontids. The tooth row of the maxilla terminates below the front margin of the antorbital fenestra, whereas it terminates further forward - below the rear of the maxillary fenestra - in Jinfengopteryx.[1]

There are ten cervical vertebrae, twelve dorsal (trunk) vertebrae, and at least sixteen caudal (tail) vertebrae in Liaoningvenator. Out of the cervicals, the third to eighth are elongated, with the fifth being the longest; among the articular processes known as prezygapophyses, the fifth cervical also has the longest. In the third and fourth cervicals, the latter like other derived troodontids, the prezygapophyses are longer than another set of processes known as the postzygapophyses. In the dorsals, the pneumatic pitting is simplified relative to Anchiornis. In the tail, the transition point - the point where the sides of the caudals become more compressed such that they are sub-triangular instead of rectangular - occurs at the seventh caudal, further forward than Sinornithoides and Mei (where it occurs at the ninth).[4][5] The longest of the caudals is the fourteenth, which is almost twice the length of the sixth. On the underside of the caudals, the chevrons are slightly curved and directed backwards, as is seen in Deinonychus.[1]

The acromion process on the scapula of Liaoningvenator is poorly developed, as in basal troodontids. Unlike basal troodontids, however, the glenoid - the arm socket - is directed vertically downwards instead of to the side. On the humerus, the deltopectoral crest extends for 40% of the bone's length, and terminates halfway down the bone. The humerus is shorter, relative to the femur, in Liaoningvenator (59% length) than in Eosinopteryx (80% length).[6] Further below, the three-digited hand is unique in that the first phalanx of the first digit is longer than the second metacarpal, at 1.49 times the length of the latter.[1]

As in Mei, the top of the ilium has a curved sinusoidal shape in Liaoningvenator. There is no crest over the acetabulum (hip socket) of Liaoningvenator, unlike Anchiornis. The rear portion of the ilium (the postacetabular process) also has a shorter bottom edge than both Anchiornis and Eosinopteryx. Uniquely, there is no process on the top end at the tip of the ischium, and the bone also has a slender obturator process. The pubis points forwards in Liaoningvenator, but backwards in Mei.[5] Additionally, the hindlimb of Liaoningvenator is twice the length of the torso, while in Mei it is 2.8 times the length of the torso. Unlike Sinovenator, Liaoningvenator has a fourth trochanter on its femur. The tibia is slender and 1.4 times the length of the femur, like Sinornithoides. The four-digited foot is highly compacted, with a tarsus that narrows toward the bottom. The third metatarsal is offset from the second and fourth, forming a trough between the latter two that is deeper than in other troodontids. Proportionally, the first phalanx of the second digit is shorter relative to the second phalanx in Liaoningvenator (135% length) than in Sinovenator (150% length).[1][7]

Discovery and naming

[edit]

Liaoningvenator is known from a single specimen, a nearly complete and well-preserved skeleton with most bones preserved in their original articulated positions. It was found in the Lujiatun Beds of the Yixian Formation in Shangyuan, Beipiao, Liaoning, China; currently, it is stored at the Dalian Natural History Museum (DNHM) in Dalian, Liaoning under the accession number DNHM D3012. Some of the specimen's snout bones are incomplete and some toe phalanges have been added by illegal fossil traders; asides from this, it is one of the most complete troodontid fossils ever found. Its head is curved forward, and its limbs are tucked in; this differs from both the classic death pose (where the head is flexed backwards), as well as the sleeping posture of Mei and Sinornithoides.[1]

In 2017, DNHM D3012 was named as the type specimen of the new genus and species Liaoningvenator curriei by Shen Caizhi, Zhao Bo, Gao Chunling, Lü Junchang, and Martin Kundrát. The genus name Liaoningvenator combines Liaoning with the suffix -venator, meaning "hunter" in Latin; the specific name curriei honors the contributions of Canadian paleontologist Philip John Currie to the research of small theropods.[1]

Shen and colleagues identified Liaoningvenator as a member of the Troodontidae based on its numerous, closely spaced teeth that are constricted below the crown; the pneumatic opening on the rear of its quadrate; the oval shape of its foramen magnum; the replacement of neural spines by shallow midline grooves in the vertebrae towards the end of its tail; the tall ascending process on its astragalus; and its asymmetrical and subarctometatarsal (i.e. where the third metatarsal is somewhat pinched by the neighboring metatarsals) foot.[2][8] They further placed it in the "higher troodontid clade" based on the lack of a bulbous capsule-like structure on the parasphenoid of its palate, and the presence of the promaxillary fenestra on its skull.[1]

Based on a phylogenetic analysis modified from a prior analysis by Takanobu Tsuihiji and colleagues in 2016, which was in turn modified from the modification by Gao and colleagues in 2012 of an analysis by Xu Xing and colleagues in 2012,[9] Shen and colleagues found that Liaoningvenator formed a unified group, or clade, with Eosinopteryx, Anchiornis, and Xiaotingia, thus offering contrary evidence to the traditional placement of these taxa as non-troodontid members of the Paraves. They are united by the teeth being flattened and recurved, with the crowns in the middle of the tooth row having heights smaller than twice their widths; the front edge of the acromion being outturned; the presence of a pronounced notch between the acromion and the coracoid; the presence of a flange on the first phalanx of the second digit on the finger; and the backward-projecting pubis.[1]

Within this clade, which Shen and colleagues did not name, Liaoningvenator formed a group with Eosinopteryx while Anchiornis formed a group with Xiaotingia. The former two are united by the lack of serrated teeth at the front of the jaw; the skull being more than 90% of the length of the femur; the cervical ribs having slender shafts and being longer than their corresponding vertebrae; and the front end of the ilium being "gently straight". Meanwhile, the latter two share the tips of the neural spines on the dorsals being fan-shaped; the coracoid being sub-triangular; the claw on the first digit of the hand being strongly arched, being higher than the top of the articulating surface; the presence of a "lip" at the top end of the claws on the second and third digits; the front edge of the pubic shaft being convex; and the claws on the third and fourth digits of the foot being strongly curved. The results of the phylogenetic analysis are reproduced in the below phylogenetic tree.[1]

Thin sections from the tibia of the holotype specimen of Liaoningvenator indicate that the cortical bone is 1.5 mm (0.059 in) thick. The cortex is divided into four zones by lines of arrested growth (LAGs), which indicates that the animal was at least four years old when it died (further LAGs may have been obliterated by the expansion of the medullary cavity). Shen and colleagues suggested, based on the thinness of the innermost zone 1 compared to zone 2, that it had partially eroded away. However, the complete zone 3 is even thinner, being only a quarter of the width of zone 2, and zone 4 is even thinner (albeit incomplete). This indicates that growth had slowed substantially by the end of the third year.[1]

Each LAG is surrounded by two bands of dense avascular (i.e. lacking openings for blood vessels) bone, which Shen and colleagues termed the "pre-annular" and "post-annular" bands. The first LAG differs from the others in that it consists of two LAGs, one weaker than the other, indicating that growth mildly slowed before the resumption of bone growth. There is no external fundamental system (EFS) on the outer rim of the bone, indicating that the holotype was still growing at the time of death. However, the decreasing thinness of zones, the presence of avascular bone in the outer layers, and evidence of bone remodeling collectively suggest that it was close to skeletal maturity.[1]

According to Shen and colleagues, Liaoningvenator is one of eleven troodontids known from China, and the fifth Early Cretaceous Chinese troodontid after Sinovenator, Sinusonasus, Mei, and Jinfengopteryx.[1] In a separate 2017 publication for which Shen was also the lead author, an additional troodontid was described, Daliansaurus, which forms the Sinovenatorinae with the former three.[10] With the exception of Jinfengopteryx, all of these troodontids lived in the Lujiatun Beds. While Shen and colleagues assigned the Lujiatun Beds to the Hauterivian epoch, newer date estimates published by Chang Su-chin and colleagues suggested a younger age of ~126 Ma for the Lujiatun Beds, which dates to the Barremian epoch.[11]

Contemporaneous dinosaurs included the microraptorine dromaeosaurid Graciliraptor; the oviraptorosaur Incisivosaurus; the ornithomimosaurs Shenzhousaurus[12] and Hexing;[13] the proceratosaurid tyrannosauroid Dilong;[12] the titanosauriform sauropod Euhelopus;[14] the ornithopod Jeholosaurus; and ceratopsians such as the ubiquitous Psittacosaurus[15] as well as Liaoceratops.[12] Mammals present included Acristatherium,[16] Gobiconodon, Juchilestes, Maotherium, Meemannodon, and Repenomamus.[17][18][19] Other tetrapods included the frogs Liaobatrachus[20] and Mesophryne;[21] and the lizard Dalinghosaurus.[22] The Lujiatun Beds consist of fluvial and volcaniclastic deposits, indicating a landscape of rivers bearing volcanoes,[1] which may have killed the preserved animals by lahar.[19] Mean annual air temperatures in the region reached a minimum of 10 °C (50 °F).[23]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Shen, C.-Z.; Zhao, B.; Gao, C.-L.; Lu, J.-C.; Kundrát, M. (2017). "A New Troodontid Dinosaur (Liaoningvenator curriei gen. et sp. nov.) from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation in Western Liaoning Province". Acta Geoscientica Sinica. 38 (3): 359–371. doi:10.3975/cagsb.2017.03.06.

- ^ a b c Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A. (2004). "Troodontidae". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 184–195.

- ^ Tsuihiji, T.; Barsbold, R.; Watabe, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Chinzorig, T.; Fujiyama, Y.; Suzuki, S. (2014). "An exquisitely preserved troodontid theropod with new information on the palatal structure from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Naturwissenschaften. 101 (2): 131–142. Bibcode:2014NW....101..131T. doi:10.1007/s00114-014-1143-9. PMID 24441791. S2CID 13920021.

- ^ Currie, P.J.; Dong, Z. (2001). "New information on Cretaceous troodontids (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the People's Republic of China" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 38 (12): 1753–1766. doi:10.1139/e01-065.

- ^ a b Gao, C.; Morschhauser, E.M.; Varricchio, D.J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, B. (2012). "A Second Soundly Sleeping Dragon: New Anatomical Details of the Chinese Troodontid Mei long with Implications for Phylogeny and Taphonomy". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045203. PMC 3459897. PMID 23028847.

- ^ Godefroit, P.; Demuynck, H.; Dyke, G.; Hu, D.; Escuillié, F.O.; Claeys, P. (2013). "Reduced plumage and flight ability of a new Jurassic paravian theropod from China". Nature Communications. 4: 1394. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1394G. doi:10.1038/ncomms2389. PMID 23340434.

- ^ Xu, X.; Zhao, Ji; Sullivan, C.; Tan, Q.-W.; Sander, M.; Ma, Q.-Y. (2012). "The taxonomy of the troodontid IVPP V 10597 reconsidered" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 50 (2): 140–150.

- ^ Turner, A.H.; Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A. (2012). "A review of dromaeosaurid systematics and paravian phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 371: 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1. hdl:2246/6352. S2CID 83572446.

- ^ Tsuihiji, T.; Barsbold, R.; Watabe, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Suzuki, S.; Hattori, S. (2016). "New material of a troodontid theropod (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Lower Cretaceous of Mongolia". Historical Biology. 28 (1–2): 128–138. doi:10.1080/08912963.2015.1005086. S2CID 128725436.

- ^ Shen, C.; Lü, J.; Liu, S.; Kundrát, M.; Brusatte, S.L.; Gao, H. (2017). "A New Troodontid Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, China" (PDF). Acta Geologica Sinica. 91 (3): 763–780. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.13307.

- ^ Chang, S.-C.; Gao, K.-Q.; Zhou, Z.-F.; Jourdan, F. (2017). "New chronostratigraphic constraints on the Yixian Formation with implications for the Jehol Biota". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 487: 399–406. Bibcode:2017PPP...487..399C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.09.026.

- ^ a b c Xu, X.; Norell, M.A. (2006). "Non-Avian dinosaur fossils from the Lower Cretaceous Jehol Group of western Liaoning, China" (PDF). Geological Journal. 41 (3–4): 419–437. doi:10.1002/gj.1044. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ Jin, L.; Jun, C.; Godefroit, P. (2012). "A New Basal Ornithomimosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation, Northeast China" (PDF). In Godefroit, P. (ed.). Bernissart Dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. Life of the Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 467–487. ISBN 978-0-253-35721-2.

- ^ Barrett, P.M.; Wang, X.-L. (2007). "Basal titanosauriform (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) teeth from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, China" (PDF). Palaeoworld. 16 (4): 265–271. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2007.07.001.

- ^ Hedrick, B.P.; Dodson, P. (2013). "Lujiatun Psittacosaurids: Understanding Individual and Taphonomic Variation Using 3D Geometric Morphometrics". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e69265. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869265H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069265. PMC 3739782. PMID 23950887.

- ^ Hu, Y.; Meng, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Y. (2010). "New basal eutherian mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota, Liaoning, China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1679): 229–236. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0203. PMC 2842663. PMID 19419990.

- ^ Wang, Y.-Q.; Hu, Y.-M.; Li, C.-K. (2006). "Review of recent advances on study of Mesozoic mammals in China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 44 (2): 193–204.

- ^ Lopatin, A.; Averianov, A. (2015). "Gobiconodon (Mammalia) from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia and Revision of Gobiconodontidae". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22 (1): 17–43. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9267-4. S2CID 18318649.

- ^ a b Jiang, B.; Fürsich, F.T.; Sha, J.; Wang, B.; Niu, Y. (2011). "Early Cretaceous volcanism and its impact on fossil preservation in Western Liaoning, NE China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 302 (3): 255–269. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.01.016.

- ^ Dong, L.; Roček, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jones, M.E.H. (2013). "Anurans from the Lower Cretaceous Jehol Group of Western Liaoning, China". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69723. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069723. PMC 3724893. PMID 23922783.

- ^ Wang, Y.; Jones, M.E.H.; Evans, S.E. (2007). "A juvenile anuran from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation, Liaoning, China" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 28 (2): 235–244. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2006.07.003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-25. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ Evans, S.E.; Wang, Y.; Jones, M.E.H. (2007). "An aggregation of lizard skeletons from the Lower Cretaceous of China". Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 87 (1): 109–118. doi:10.1007/BF03043910. S2CID 83907519.

- ^ Amiot, R.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Ding, Z.; Fluteau, F.; Hibino, T.; Kusuhashi, N.; Mo, J.; Suteethorn, V.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, F. (2011). "Oxygen isotopes of East Asian dinosaurs reveal exceptionally cold Early Cretaceous climates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (13): 5179–5183. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011369108. PMC 3069172. PMID 21393569.