Davey Williams – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Davey Williams did not much like being the answer to a trivia question, but he was. The question is: Who caught the relay when Willie Mays made his famous over-the-shoulder catch against Vic Wertz in the 1954 World Series? Williams was the Giants’ second baseman and did in fact take the relay throw to hold Larry Doby, who had tagged up from second base, at third. Davey once remarked that if the camera had followed the ball after Mays’s whirling-dervish throw after the catch, he would have been on TV more than Dave Garroway.1

Davey Williams did not much like being the answer to a trivia question, but he was. The question is: Who caught the relay when Willie Mays made his famous over-the-shoulder catch against Vic Wertz in the 1954 World Series? Williams was the Giants’ second baseman and did in fact take the relay throw to hold Larry Doby, who had tagged up from second base, at third. Davey once remarked that if the camera had followed the ball after Mays’s whirling-dervish throw after the catch, he would have been on TV more than Dave Garroway.1

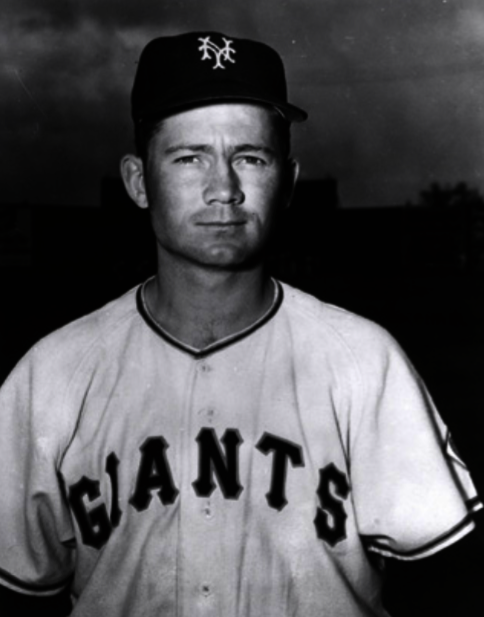

Of course, Davey Williams should be remembered for more than that famous play. He was the Giants’ regular second baseman for the better part of four seasons. He was named to the 1953 NL All-Star team, a year in which he hit .297, and showed the ability to become one of the premier second basemen in baseball. But a serious back injury, the cause of which there was a good deal of debate over, forced him to end his playing career when he was only 27 years old.

David Carlous Williams, Jr. was born on November 2, 1927, in Dallas, Texas, where he lived his entire life, to David Carlous Williams, Sr. and the former Eva Cleo Haire. Davey’s parents co-owned the Jim Town Grocery in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas.2 Davey Sr. had played minor-league baseball in the Arizona-New Mexico League and Davey Jr. may have inherited his considerable athletic ability from him. While growing up he worked as an usher at Burnett Field, home of the Dallas Eagles of the Texas League, so that he could get into the park free and watch the games. He also played on various Dallas youth baseball teams with and against the likes of Doak Walker and Bobby Layne.3

Although only 5-feet-9, Davey was a four-sport star at Sunset High School in Dallas, lettering in football (as a 141-pound running back), basketball, and track. Baseball was where he really shone.4 In fact, in his senior year as captain he led his team to the state baseball championship. That summer Davey was selected to represent Texas in the 1945 Esquire Magazine Boys’ All-American baseball game, to be played in the Polo Grounds in New York City, where he would return in a few years to play second base for the Giants.

The game matched the East versus the West, with none other than Babe Ruth managing the East and Ty Cobb managing the West. In the first inning Davey walked and then slid hard into second base on a double-play groundball. The opposing shortstop came down on Davey’s hand and nearly tore the nail off one of his fingers. Williams was afraid that Cobb would pull him out of the game in the first inning, so hid his hand when he went back into the dugout. He went into the corner of the dugout, tore the rest of the nail off, put some tape over it, and played eight innings of the game.5 He even managed to knock a base hit off southpaw phenom Curt Simmons.6

The next morning Davey was in the lobby of the New Yorker Hotel, where the team was staying, when Ty Cobb came over and asked to see his hand. Davey peeled the tape off and showed him. A couple of months later Davey received a letter from Cobb, telling him how he had endeared himself to Cobb by not letting anyone see his injury and just playing through it.7

Immediately after the game, a number of scouts had wanted to talk to Williams, but he was nowhere to be found. He had quickly slipped out of the clubhouse to go see the Bronx Zoo. As it turned out, Davey wasn’t interested in a professional career just yet because he had planned to attend the University of Texas and play baseball for the legendary coach Billy Disch.8

But plans changed when Williams returned home and learned that he might be drafted, even though World War II was winding down. He enrolled in Southern Methodist University, but decided to sign a pro contract and then enlist to get his service obligation out of the way. Although several major-league organizations wanted him, Davey decided to sign with the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. Their scout, Claude Dietrich, convinced him that signing with the Crackers was a faster way to the big leagues than, say, signing with a big-league club like the Cardinals, where Red Schoendienst was likely to be entrenched at second base for years. Dietrich told Williams that if he had a good year or two with the Crackers, they could sell him to any of the 16 major-league clubs that needed a second baseman.9

Upon enlisting, Williams was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he went to airborne school and trained as a paratrooper. He was about to be shipped overseas when a baseball-savvy major pulled his orders so that he could play for the base team.10 After 14 months in the service, Williams was discharged and was able to join the Crackers for spring training in 1947 in Gainesville, Florida.11

In those days, top minor-league teams had working agreements with clubs lower down the totem pole, and so the 19-year-old Williams was assigned to Waycross in the Class D Georgia-Florida League. Williams broke into professional baseball by hitting .282 for the second-place Bears, scoring a league-leading 147 runs, and being named as the second baseman on the league all-star team.

After the season, on January 16, 1948, Davey married his high-school sweetheart, Joy Elizabeth Reed. The couple would have four children, three girls and a boy.12

Davey’s 1947 performance in Waycross earned him a promotion to Class B, the Pensacola Fliers in the Southeastern League. There he batted .308 and again led the league in runs scored with 119 and made the league all-star team as its top second baseman.13

Davey was drawing rave reviews, and after the season the New York Giants purchased his contract from the Crackers for $50,000 and two players, with the understanding that he would spend 1949 with Atlanta.14 He proceeded to hit a solid .290 for the Crackers and for the third year in a row was named his league’s all-star second baseman. That performance earned the 21-year-old Williams a late-season call-up to the Giants. There he batted .240 in 13 games and 58 plate appearances. He also had the thrill of hitting his first major-league home run, connecting on September 19 with two out and a runner on against Harry Gumbert of the Pirates in the 10th inning at Forbes Field to propel the Giants to a 6-4 victory.

It appeared that Davey was in line to become the Giants’ regular second baseman in 1950. However, on December 14, 1949, the Giants pulled off a blockbuster six-man trade, a key part of which involved the acquisition of second baseman Eddie Stanky from the Boston Braves. With Stanky installed at second, the Giants sent Williams to Minneapolis in the American Association for further seasoning. Before they sent him out, Williams remembered overhearing a sportswriter tell the Giants’ chief scout, Tom Sheehan, “You better get Williams the hell outta here and quit playing him. Otherwise you’re going to have a hard time telling the sportswriters why you’re sending him out. The little sonofabitch is playing great. You better get rid of him now.”15

Once in Minneapolis Williams helped the Millers to the pennant, hitting .280 in 616 plate appearances and leading the league with 113 runs scored. Davey also showed surprising muscle, blasting 17 home runs, with a .450 slugging average and an .819 OPS. He fielded .973 to lead second basemen in that category.

But during the season Williams suffered an injury that was to plague him for the rest of his career. He was racing back for a popup when he collided with the right fielder, whose knee caught him at the base of the spine.16 It was the start of a chronic back condition that would eventually shorten Williams’s career.

Stanky was still entrenched at second base for the Giants, so the 23-year-old Williams was back with the Millers for the start of the 1951 campaign. He wouldn’t finish the year there, however. After he batted .287 and slugged 12 home runs in 80 games, including four consecutive four-baggers over a two-game span on June 26 and 27, the Giants called him up at the All-Star break to spell Stanky at second and in the leadoff slot.17 Williams arrived with a bang. On July 13, in his second appearance of the season with New York, Davey stroked three hits in six at-bats with a grand slam and a total of five runs batted in a 14-4 win over the St. Louis Cardinals.

The Giants were in second place, but eight games out of first when Williams joined the club. He thought that even manager Leo Durocher had given up on the pennant race, recalling a game in which Durocher was sitting down at the end of the dugout with his sleeves rolled up getting a suntan while he had two pitchers, Sal Maglie and Larry Jansen, coaching the bases.18

Like most of his teammates, Davey’s relationship with the volatile Durocher would have its ups and downs. Once Davey, playing second base, managed to get only one out on what should have been a double-play groundball. The extra out gave the opposition a chance to score three runs. “By the time I got back to the dugout,” Williams remembered, “Leo was already in my face, chewing me out. I tried to avoid him by walking down to the other end of the dugout and sitting alone, but he came right after me, leaning over and saying all kinds of hurtful things. Finally, I just got up and walked down the tunnel and into the clubhouse to get away. It didn’t happen. Leo followed me there and continued to yell and rant. Eventually I just could not take it anymore. I picked up this full ice chest and just threw it across the room in his direction. It made an awful lot of noise, but it did the trick. Only then did Leo turn, go away, and leave me alone.”19

Davey saw a lot of action for the balance of July and early August after his call-up in 1951. Once the Giants began their famous run to the pennant in mid-August, however, Durocher went with the veteran Stanky at second base and Williams was relegated to pinch-running and late-inning defensive work to help seal victories. For the season, he appeared in 30 games and in 70 plate appearances batted a respectable .266. In the field he handled 81 chances flawlessly for a 1.000 fielding percentage.

He appeared only as a pinch-runner in one of the three playoff games against the Dodgers. In the fabled third game, Williams was sitting on the bench in the ninth inning next to fellow reserve Jack Lohrke. Jackie Robinson went out to the mound to shake Dodger pitcher Don Newcombe’s hand at the start of the bottom of the inning, causing Lohrke to turn and say to Davey, “Know what, piss on the fire and I’ll call the dogs. I think the hunt’s over.”20

Newcombe was pitching so well with a 4-1 lead that many of the Giants thought the game was effectively over. Of course, it wasn’t over by a long shot. During the inning, Don Mueller badly mangled his ankle sliding into third base after Whitey Lockman doubled off Newcombe, which brought the score to 4-2. As Mueller was carried from the field, Williams seemed to be the logical pinch-runner since Durocher had used him in that capacity 10 times since his July call-up. But Leo went with the more experienced Clint Hartung, even though he had only pinch-run once that season, so Williams remained glued to the bench when Bobby Thomson hit his famous home run.21

Williams saw little action in the six-game World Series, unsuccessfully pinch-hitting against Eddie Lopat and pinch-running on another occasion. But on December 11, the Giants traded Eddie Stanky to the Cardinals so that he could become their manager, effectively paving the way for Davey to take over second base.22

He did so with authority, teaming up with shortstop Alvin Dark to form an excellent double-play combination. He slugged 13 home runs in 138 games and hit .254 as the Giants won 92 games but finished in second place, 4½ games behind the Dodgers. His bad back took another blow that year, however, when Gil Hodges plowed into him trying to break up a double play, shelving Williams for a number of games and causing him to play in pain.23

Nonetheless, Williams had established himself at second base going into the 1953 season, and although again plagued by back problems, hit an impressive .297 in 112 games. All-Star Game manager Charlie Dressen even selected him for the National League to back up Red Schoendienst at second base. Davey’s selection was not without controversy, however, since he had finished fourth in the fan balloting behind Schoendienst, Jack Dittmer of the Braves, and Connie Ryan of the Phillies. In the face of criticism, Dressen simply said, “Williams is a damn good ballplayer.”24 As it was, Williams was the only Giant to play in the 1953 All-Star game.

In the game itself, which was played at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, Davey replaced Schoendienst in the top of the seventh and drew a walk in the bottom of the inning against Mike Garcia in his only at-bat. In the field, he made the last out of the game, catching Yogi Berra’s towering ninth inning popup to seal the National League’s 5-1 win.

Davey regarded playing in that All-Star Game as one of his biggest thrills in baseball and lamented that if he’d just dropped Berra’s popup they could still be playing.25

The 1954 season was a special one for the Giants as they burst into the lead in the middle of June and never looked back, winning 97 games and finishing five games ahead of second-place Brooklyn. Williams was an integral part, starting 142 games for the Giants at second base. Although he slumped at the plate to hit only .222, he led National League second basemen with a .982 fielding average while committing just 14 errors.

His hitting slump continued into the World Series, where the Giants faced the Cleveland Indians, who had won a record 111 games to sweep to the American League pennant. Davey played every inning of the Giants’ surprising four-game sweep, but went hitless in 12 plate appearances. He did, however, execute a perfect suicide squeeze in the top of the third in Game Three to give his Giants a 4-0 lead in a game they would win 6-2.26

During the same game Williams got hold of a Garcia fastball and hit it out of the park, only about a foot foul. Running hard, he was already around second base and had to come back by the mound on his way to the plate. Garcia said, “I must have made that a bit too good.”

“You must have if I hit it that well,” Davey replied.27

In the early spring of 1955, Davey Williams became an unwitting victim of the Giants-Dodgers rivalry, which was particularly intense in the 1950s. It was often fueled by the Giants’ Sal Maglie, who made his mark by throwing at batters “whenever they didn’t expect it. That way I had them looking to duck all the time.”28

In the second inning of a game at Ebbets Field on April 23, Maglie directed a pitch behind Jackie Robinson’s head after hitting Sandy Amoros leading off the inning. Robinson struck out, but on his next at-bat, he bunted down the first-base line, hoping to run over Maglie when he came over to field the ball.29 Even though the score was tied, Maglie made no move to cover the bunt, so after a moment’s hesitation, first baseman Whitey Lockman raced in for the ball while Williams, playing second base, sped over to cover first base. When the ball arrived from Lockman, Williams was at a dead stop at the bag. Robinson, a former All-American running back at UCLA, hit him like a freight train and knocked him sprawling in the dust, where he landed on his left shoulder. Even so, Williams somehow managed to hang on to the ball for the out.

Although some accounts have Williams being carried from the field after being run over by Robinson,30 in reality he refused to come out of the game, playing until Dusty Rhodes pinch-hit for him in the bottom of the ninth inning.31 The next day Durocher sent Williams up to pinch-hit in the top of the ninth against Billy Loes with the Giants down by two runs. Loes greeted Williams with a brushback pitch, before Williams surprised everyone by hitting a long fly out to left field.32

Afterward Williams continued to try to grind it out, playing even though he could barely lift his arm. In fact, he went 4-for-4 on April 30 against the St. Louis Cardinals. But as the season wore on, Williams’s back continued to plague him and there were a number of days when he simply could not take the field.

On May 28, 1955, in the Polo Grounds, Williams got some measure of revenge against the Dodgers in a nationally televised game. In the top of the fourth inning with runners on first and second with no outs, Jackie Robinson lifted a Texas Leaguer toward right-center field. The Dodgers baserunners, Gil Hodges on second and Carl Furillo on first, were off and running, thinking that no one could reach the ball. But Williams raced back from second base and made a tremendous juggling, over-the-shoulder catch at full speed, before spinning and throwing to Al Dark covering second to double up Hodges. Dark then threw to Whitey Lockman at first to complete a triple play.33

Then on July 31 in Milwaukee, Williams wrenched his back anew sliding into home plate and had to roll over on all fours to get off the ground. He managed to stay in the game until after his next at-bat, when he was replaced by Wayne Terwilliger. It was Williams’s last appearance in a major-league game. The next day the Giants sent him to the Mayo Clinic, where he was diagnosed with an arthritic spinal condition. The doctors told him that there was no cure to his back condition and said that if he continued to play baseball he risked becoming crippled. As a result, Williams was forced to retire from baseball in the middle of the 1955 season at the age of 27.34

Robinson’s running over of Williams probably contributed to the premature ending of his playing career. Williams, however, admired Robinson, even though Jackie once told Howard Cosell that Davey was the only guy he had ever tried to hurt on purpose.35 According to Williams, Robinson was a great competitor who had taken “all the guff anybody could possibly take.” Williams, however, was sorry that, after having survived all the harassment and shown what a great player he was, “at the end of his career he had to turn it around and try to get even with everybody.”36

Williams’s former teammate Bill Rigney succeeded Leo Durocher as manager of the Giants in 1956 and hired Williams as a coach. But after two straight sixth-place finishes, Rigney decided to hire all new coaches when the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958. Williams landed a job back in his hometown as manager of the Dallas Rangers of the Texas League. Still just 30 years old, he put himself on the active roster and batted .303 in 39 plate appearances before getting crossways with the owner and general manager and being replaced about halfway through the season.

Afterward, Williams left baseball behind and worked as criminal investigator for Dallas County and later as an expediter for a company that made heavy equipment for the government and for companies like McDonnell-Douglas and Bell Helicopter.37 Williams lost his wife, Joy, to a brain aneurysm in 1984. He never remarried but had a longtime companion, a family friend named Sue Cates, who had lost her husband about a year before Joy died.38

Davey Williams died on August 17, 2009, in Farmers Branch, a Dallas suburb. He was 81 years old. But for a chronic back condition, he might well have been the perennial National League All-Star second baseman of his time instead of being forced to retire as he entered his prime.39 As it is, Williams may be the third-best player ever out of Dallas, surpassed only by Ernie Banks and more recently Clayton Kershaw.

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Books

Golenbock, Peter, Bums – An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984).

Heiman, Lee, Dave Weiner, and Bill Gutman, When the Cheering Stops … Former Major Leaguers Talk About Their Game and Their Lives (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1990).

Hynd, Noel, The Giants of the Polo Grounds (New York: Doubleday, 1988).

Irvin, Monte, with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First – the Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997, 2nd ed.).

Kahn, Roger, The Boys of Summer (New York: Harper & Row, 1971).

Kahn, Roger, and Rob Miraldi (editor), Beyond the Boys of Summer: The Very Best of Roger Kahn (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005).

Kiernan, Thomas, The Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1975).

Meany, Tom, Those Incredible Giants (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1955).

O’Neal, Bill, The American Association – A Baseball History 1902-1991 (Austin: Eakin Press, 1991).

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green – the Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Random House, Inc., 2006).

Rosenfeld, Harvey, The Great Chase – the Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1992).

Szalontai, James, D., Close Shave – The Life and Times of Baseball’s Sal Maglie (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2002).

Testa, Judith, Sal Maglie – Baseball’s Demon Barber (Dekalb, Illnois: Northern Illinois Univ. Press, 2007).

Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, and David. W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Articles

Heryford, Merle, “Dallas Davey (Williams),” Baseball Digest, March 1952.

Kelley, Brent, “Davey Williams, One of the Nice Guys,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 6, 1990.

“A Bonus for TV’s Millions,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1955.

Websites

Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1. When the Cheering Stops …, 215.

2. Email correspondence with Lisa Williams-Grosso, May 26, 2014.

3 When the Cheering Stops …, 217.

4. Merle Heryford, “Dallas Davey,” Baseball Digest, March 1952, 73.

5. When the Cheering Stops …, 218.

6. “Dallas Davey,” 73.

7. When the Cheering Stops …, 218.

8. “Dallas Davey,” 73.

9. Brent Kelley, “Davey Williams, One of the Nice Guys,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 6, 1990, 260.

10. “Dallas Davey,” 74.

11. When the Cheering Stops …, 219.

12. The children were David Wayne Williams, born on October 16, 1949; Linda Kaye Williams, born on January 6, 1951; Lisa Williams, born on November 4, 1955; and Lori Lea Williams, born on January 5, 1960. David died in 1995 and Linda died in 2004, both while Davey Williams was still alive.

13. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed., 363, 369.

14. Tom Meany, The Incredible Giants, 161-62; “Dallas Davey,” 74. Williams’s recollection was that the Giants paid $65,000 and two players for him. When the Cheering Stops …, 219.

15 When the Cheering Stops …, 216.

16. The Incredible Giants, 164.

17. Bill O’Neal, The American Association, 115; “Dallas Davey,” 72.

18. According to Williams, “We’re maybe thirteen, fourteen, or fifteen games out and Leo is already at the beach.” When the Cheering Stops …, 219.

19. Email from Bill McCurdy, recounting April 19, 2008, interview with Davey Williams.

20. When the Cheering Stops …, 220.

21. Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green – the Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World, 209-210. Of course, Durocher may have not wanted to waste Williams as a pinch-runner since Mueller was not the tying or winning run.

22 “Dallas Davey,” 71-72.

23. Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First – the Autobiography of Monte Irwin, 143; When the Cheering Stops …, 221.

24. David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David. W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic, 126.

25. “Davey Williams, One of the Nice Guys,” 262.

26. Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds, 376; The Incredible Giants, 165.

27. baseballhappenings.net/2009/08/davey-williams-81-192.

28. Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer, 395.

29. According to one source, Robinson had bunted down the first-base line on Maglie twice before, sending Maglie sprawling the first time while the second time Maglie had avoided fielding the bunt. Judith Testa, Sal Maglie – Baseball’s Demon Barber, 246.

30. The Boys of Summer, 396; Peter Golenbock, Bums – An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers, 285-86.

31. James D. Szalontai, Close Shave – The Life and Times of Baseball’s Sal Maglie, 286.

32. In Williams’s recollection, Carl Erskine brushed him back. “Davey Williams, One of the Nice Guys, 261, When the Cheering Stops …, 222. In reality it was Billy Loes. After an error, Al Dark hit a two-run home run off Loes to tie the score, 5-5. The Giants then scored six runs in the top of the 10th inning to go ahead 11-5 while the Dodgers countered with five runs in the bottom half to just fall short, 11-10.

33 Photos of Williams’s juggling catch were featured in the June 6, 1955, Sports Illustrated, 29.

34. When the Cheering Stops …, 224.

35. When the Cheering Stops …, 221.

36. When the Cheering Stops …, 222. Jackie Robinson surprisingly later told Roger Kahn that the aftermath of his running over Davey Williams was his toughest stretch in baseball, tougher even than when he broke the color line in 1947. According to Robinson, he never thought of quitting when he broke in, because there was too much to fight for. But after he ran over Williams, he did think of quitting because then all he was fighting for was to win. Roger Kahn, Beyond the Boys of Summer: The Very Best of Roger Kahn, 259-60.

37. When the Cheering Stops …, 225-226.

38. Email correspondence with Lisa Williams-Grosso, May 26, 2014.

39. Max Lanier, a pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals who was traded to the New York Giants and became Williams’s teammate, once told him that he covered twice as much ground at second base as Red Schoendienst, who was the National League’s premier second baseman in the 1950s. “Davey Williams, One of the Nice Guys,” 261.