Rod Gaspar – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

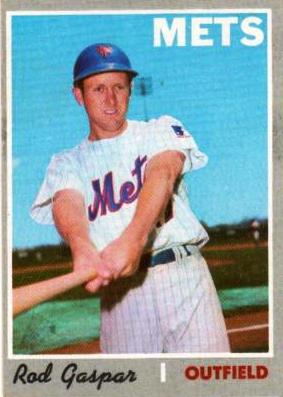

Though his major-league career was limited to parts of four seasons, Rod Gaspar was anything but a footnote player. While he played in only one full year in the majors, it was as a World Champion. Gaspar led National League outfielders in double plays while scoring a pivotal run in the 1969 World Series. Six years later, he witnessed a second baseball “Miracle” in Honolulu. Wherever he played, Gaspar was known for his spectacular outfield play and his late-inning heroics. Retiring from baseball at the age of 30, Gaspar successfully made the transition to a second career in the financial services industry.

Rodney Earl Gaspar was born on April 3, 1946 in Long Beach, California. The son of an ironworker and a homemaker, he and his two brothers were raised in a working class upbringing.1 Gaspar was initially noted as a good athlete at Lakewood High School. Playing baseball and basketball, he was an All-City athlete in 1964, his senior year.2 On the diamond, he was particularly adept at hitting for average, baserunning, and defense in the outfield. His baseball acumen earned him a scholarship to Long Beach State College.3 The New York Mets thought enough of Gaspar, drafting him in 1966 after he batted .393. He decided to remain in school, hitting .342 in his junior year. The Mets drafted Gaspar once again in June 1967. This time, he signed with scouts Nelson Burbrink and Dee Fondy.4 Rod Gaspar was on his way Williamsport. Although Gaspar hit only .260 at the Mets’ Double-A affiliate, it was enough to place him as one of the top 10 hitters in the Eastern League. Gaspar remembers:

“We played in a pitcher’s league. The air was heavy and the lights in most of the ballparks were not good. In Pawtucket, the sun would set in center field. There was only one guy who hit .300 and that was my teammate, Bernie Smith – he hit exactly .300 [.306, actually].”5 The Mets moved their AA affiliate to Memphis in 1968, where Gaspar proceeded to tear up the opposition; leading the league with 160 hits, he batted .309 with 25 stolen bases, earning a Texas League All-Star berth. Gaspar then reported to the Mexican Winter League, again batting better than .300.6 The young outfielder continued his meteoric rise through the Mets’ farm system, receiving an invitation to training camp at St. Petersburg in 1969. But could the switch hitter who stood 6’0” and weighed 160 pounds crack a roster already boasting Tommie Agee, Cleon Jones, and Ron Swoboda in the outfield? Gaspar described the situation to Stanley Cohen as follows:

“I was just up from Memphis and they didn’t know who I was. [Mr.] Hodges didn’t know who I was, the coaches didn’t know. No one did.”7 Gaspar appeared destined for AAA Tidewater when fourth outfielder Art Shamsky hurt his back. “Gil started me in the outfield and I went on a hitting streak. I think I hit in thirteen straight games and they ended up keeping me.”8

Gaspar learned on his 23rd birthday that he made the team; as he told sportswriter Ferd Borsch “I was at the right place at the right time.”9 His greatest thrill at that time in his career was being told he was the Mets’ starting right fielder against the expansion Montreal Expos on Opening Day, April 8, 1969. Batting 2-for-5 with a stolen base and an RBI, he remarked that “the thrill of being out there will always be with me.”10 With the tying run on second base, he struck out against Carroll Sembera to end the game, an 11-10 victory for the Expos. Having lost their previous seven National League openers, the Mets continued their tradition of beginning each season below .500.

Although relegated to supporting roles when Shamsky returned from the disabled list, Gaspar was often recalled in clutch situations, rarely disappointing his manager or his fans. He credits Gil Hodges for understanding and using the talents of all his players to field a formidable club.

“[Gil] really knew how to utilize his personnel. I always felt a part of the club. I know I wasn’t a star but I knew I was a contributor.” Gaspar added that Hodges “made every player feel a part of that unit and vitally important to the team’s success.”11 Even today, Gaspar remains enthusiastic when describing the symbiosis he shared with Mets fans, calling them “the best, the most energetic, and among the most passionate in baseball.”

Gaspar saved two of his most monumental efforts for games against teams from California. On May 30 before a crowd of 52,272, he hit a home run off the Giants’ Mike McCormick. His teammates rallied to overcome a 3-1 deficit, tying the game and ultimately winning 4-3. It was the second victory in an 11-game winning streak for the Mets. A week later, on June 7 in San Diego, Gaspar rapped a triple off Jack Baldschun in a 4-0 rout of the Padres. Perhaps the most unusual game of Gaspar’s rookie season occurred on August 30 at Candlestick Park. As the Mets and Giants were deadlocked in the bottom of the ninth, Gaspar was in left field as Willie McCovey strode to the plate.

“McCovey was the league MVP that year and I think they intentionally walked him more than any other player.”12 With one away and Bob Burda representing the go-ahead run on first base, Gil Hodges had Tug McGraw pitch to McCovey. The Mets decided to play the percentages by invoking “the McCovey shift” Donn Clendenon stood at first, Tommie Agee played in center-right field, and Gaspar shifted to left-center field. This is how Gaspar remembers the play to have unfolded.

“As soon as McCovey hits the ball, [Burda] takes off. We were playing in Candlestick Park, and if you’re familiar with the weather in San Francisco, you’d know that the field was wet. He hits ‘a high fly ball down the left field line’ as our announcer Bob Murphy describes it and it lands fair [by a foot], near the warning track. There was no way I could catch the ball. My only thought was Burda was the winning run and I had to throw him out at home plate. As I approached the ball it was stuck in the ground. I grabbed it bare-handed pivoted off my left foot and threw blindly toward home plate. Thankfully it was ‘a strike’ to catcher Jerry Grote.”13

As Gaspar remembered the play, Grote must have been shocked by the long throw to forget that Burda was only the second out. The catcher rolled the ball to the pitcher’s mound. Donn Clendenon, one of impeccable mental alertness, raced to the mound to field the ball, threw it to Bobby Pfeil to nab McCovey at third base. That was a 7-2-3-5 double play for those keeping score. The Mets went on to win the game 3-2 when Clendenon hit a solo home run off Gaylord Perry in the 10th inning.

When the dust cleared on the 1969 pennant race, the Mets sat atop the National League East division, finishing ahead of the Cubs by eight games. Amid a surplus of talented outfielders, Rod Gaspar led the senior circuit with six double plays in 118 chances. He also led the Mets with a dozen assists while stealing seven bases in 10 tries. At the plate, he batted .228. However, despite winning 100 games and sweeping the favored Atlanta Braves in the National League Championship Series, not everyone took the Mets seriously on the eve of the World Series – least of all, Frank Robinson of the American League Champion Baltimore Orioles.

After the Orioles had swept the Minnesota Twins in the American League playoff, Robinson had heard that Rod Gaspar said the Mets would win the World Series in four straight games. Robinson said “who in the hell is Ron Gaspar?” Fellow Baltimore outfielder Paul Blair eavesdropped on Robinson’s sarcasm, correcting him: “That’s not Ron. It’s Rod, stupid!” In a retort worthy of an Abbott and Costello routine, Robinson said, “All right, bring on Rod Stupid.”14 Notwithstanding Robinson’s overconfidence, the Mets and Rod Gaspar enjoyed the last laugh in Game Four. With the score deadlocked at 1 in the 10th inning, the Mets summoned J. C. Martin as a pinch-hitter for Tom Seaver. Martin laid down a perfect bunt down the first-base line. Orioles pitcher Pete Richert fielded the ball. Intending to make the throw to Boog Powell, Richert instead hit Martin on the wrist. Meanwhile, Rod Gaspar was racing home from second base. As the ball bounced away, Gaspar scored the winning run. As he remembered the play, “I could see it hit and I just took off. Eddie Yost, our third base coach, [who stood only two feet away] was screaming for me to go home, but I never heard him. There were over 55,000 people there and the noise was incredible. Only after I turned and saw the ball rolling toward second base that I took off for home and scored. The first person to greet me was the winning pitcher, Tom Seaver. It was his only World Series victory in his career.”15

Manager Gil Hodges did not resort to his bench in Game Five, a 5-3 triumph to win the Mets their first-ever World Championship. Quite literally, the Miracle Mets were the “toast of the town,” appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show after winning the World Series. New York was an exciting city to be young and famous and Rod Gaspar enjoyed every minute of the 1969 season. Gary Gentry was his roommate and he developed close friendships with other young teammates such as Wayne Garrett, Ken Boswell, Art Shamsky, Bobby Pfeil, and Danny Frisella. Frisella grew to serve an important role in Gaspar’s personal life when in April 1970, the relief pitcher known as “the Bear” introduced him to Sheridan Poulton.16 Rod and Sheridan married three months later, on July 7, 1970.

Despite the personal milestone, 1970 was a bittersweet season for Rod Gaspar. On the heels of winning a World Series in his rookie year, he spent most of the year in Triple-A Tidewater, Virginia. Looking back on the season, Gaspar blamed only his “nicklebrained attitude” for failing to make the big club.17

“For the first time in my life, I didn’t work out after the 1969 season. Gil wanted me to play in Venezuela. I said ‘Heck, why do I have to go down there?’ So I didn’t play any ball over the winter and I reported to spring training out of shape.” He added that “if I hadn’t been sent down to the minors, there was something wrong with them. I should have been sent down.”18 Playing for Tidewater, Gaspar found his swing, batting .318 with 37 runs batted in. When he was recalled, the Mets found themselves embroiled in a pennant race with the Cubs and the Pirates. Seeking a right arm as bullpen insurance, the Mets acquired pitcher Ron Herbel from the Padres on September 1. While Herbel pitched well, limiting hitters to 1.38 earned runs in 13 innings, the Mets fell short of a second consecutive division title. Meanwhile, as the Mets still owed the Padres one player, Gaspar was dispatched to San Diego on December 20. Watching Gaspar as a Met, Padres’ president Buzzie Bavasi remarked that he “made you like him because he hustled and played hard all the time.”19

Rod Gaspar attended the Padres’ spring training camp in Yuma, Arizona in 1971, one of eight candidates vying for a starting outfield role. Though considered by many to be the leading contender to play left field, Gaspar again had a bad spring training. Manager Preston Gomez optioned Gaspar once again to Triple A, to the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League.20 Hawaii enjoyed an unusual arrangement as the Padres’ top farm club. In an attempt to bring major-league baseball to Honolulu, general manager Jack Quinn signed his own players, operating a farm system, and even participated in the amateur draft independent from any big league organization.21 Gaspar joined a roster loaded with well-travelled veterans including Merritt Ranew, Tom Satriano, Leon Wagner, and Steve Whitaker. Quinn added additional credibility to his bid for a big-league franchise on June 16 when he signed free agent third baseman Clete Boyer.22

One of those players was Dave Baldwin, who lived in the same apartment complex as Gaspar. Acquired in a cash deal with the Milwaukee Brewers prior to the 1971 season, Baldwin remembered Gaspar’s “great range” and his ability to “go get ‘em in the outfield.”23 As a smart baserunner with a keen eye at the plate, Baldwin saw Gaspar as an ideal complement to the older players in the Islanders lineup. Extra-inning heroics remained a specialty of Gaspar’s. Hosting Tacoma on April 12, the Islanders were tied at two in the 10th inning when Gaspar delivered a two-out single to score Rafael Robles as the go-ahead run. Two nights later, Gaspar hit his only home run of the season Hawaii shut out Tacoma 6-0.24 Gaspar’s all-around hustle most pronounced by skydiving catches earned ovations from the Honolulu Stadium crowd. As Dave Baldwin remembers, they brought a unique brand of fandom to the baseball diamond:

“They always had a great time whether we won or lost. In addition, the weather was always perfect for baseball. Many of the women dressed in leis and muumuus. The stadium was ideal for the fans – they felt close to the action, a part of the game. They would yell out advice to us about putting on the hit-and-run or shading the outfield to the left for a particular hitter. The fans helped the players play better, something I never saw on the mainland.”25 One year earlier, Hawaii fans supported the team in droves, nearly outdrawing the Chicago White Sox as the Islanders decimated the Pacific Coast League with a record of 98-48.26 Vendors at Honolulu Stadium offered concession items including sashimi, poi, and boiled peanuts. Pitching for the Vancouver Mounties in 1969, Jim Bouton remembers sampling siamin soup – a concoction of shredded pork, noodles, and native herbs – while awaiting his turn to pitch from the bullpen.27

By the end of May, Gaspar was batting .326, including an astonishing .500 in 120 at bats as a leadoff hitter. Only once in the first two months did he fail to reach base. 28 Gaspar set an Islanders’ record for walks with 107 while batting .274 and stealing 26 bases. 29 In September, Gaspar was promoted to San Diego where he went 2-for 17.

Gaspar remained under contract with the Padres organization throughout his tenure in Honolulu, and this status would play a pivotal role as his baseball career evolved. In 1970, Mets general manager Bob Scheffing offered Gaspar a raise from the minimum 10,000to10,000 to 10,000to19,000, a salary he earned again in 1971. When demoted to Hawaii once again in 1972, Gaspar was removed from the Padres’ 40-man roster. Accordingly, general manager Edwin Leishman restructured his contract to a minor-league deal which paid $2,000 a month. Under the reserve clause, their actions were standard procedure among baseball executives. Gaspar felt differently.

“Knowing me at the time, I probably said that ‘I’m not going to sign that.’ Leishman basically told me that if I wouldn’t sign, I could stay in Hawaii. We had a relief pitcher named Al Severinsen who felt strongly about what other players were offered in their contracts. He felt badly for my situation and encouraged me to negotiate for my 1971 salary.”30 Gaspar filed a grievance with major-league baseball, which he won; thus, he was entitled to receive the $7,000 differential at the end of the season.

Regardless, Gaspar batted only .234 in 111 at-bats for the Islanders in 1972 50. Manager Rocky Bridges did not play him regularly and on July 1, the Padres loaned his contract to the Cincinnati Reds. Reporting to the Indianapolis Indians, Gaspar made his presence known immediately when on July 4, he scored the winning run on a bases-loaded 12th inning single.31 His highlight with the Indians came on July 26 with the score tied at three in the bottom of the ninth. Gaspar batted right to homer off Don Shaw, scoring Ed Armbrister from first base and winning the game, 5-3.32

Though opening the 1973 campaign on the Islanders’ bench, Gaspar earned a spot in the starting lineup by the end of April. What transpired was another .300 season in which he drove 48 runs. Gaspar partially attributed his regained success to new manager Roy Hartsfield. Replacing Bridges on May 21, Hartsfield extolled Gaspar as “a consistent hitter” whose “fielding speaks for itself,” adding that “he deserves another chance in the majors.”33 Gaspar proved his manager’s fielding report when he executed thirteen spectacular catches in the span of two days. Catching a 430 foot moonshot at the center-field gate on June 23, he robbed Eugene’s Bob Spence of a probably inside the park home run. The next day, Gaspar rapped a triple with the bases loaded before leaping over center field to deprive Dick Wissel of a home run.

Gaspar began the 1974 season yet again in Hawaii, but was recalled to the Padres in May.34 However, after batting a disappointing 3-for-14, he was demoted to Hawaii after the All-Star break.35 By now, it was apparent that without a modern playing facility, Jack Quinn could never succeed at bringing a major-league franchise to the Aloha State. While the promising Aloha Stadium was under construction, it would not be ready for baseball until 1976.36 In the meantime, the Islanders were relegated to the now-derelict Honolulu Stadium. Neither American nor National League could endorse a ballpark with a miniscule grandstand and only 81 parking spaces. Furthermore, Honolulu Stadium was nicknamed “the Termite Palace” for a reason. Dave Baldwin, later a systems engineer, offered the following structural report:

“The well-known joke was that all the termites were holding hands, but if they ever let go, the whole thing would fall apart. Termites weren’t the only problem. The electrical wiring system ran under the playing field, but no one had a diagram of this. If a mole gnawed through a wire, a bank of lights might go out and it would have to be completely rewired.”37 Amid pestilence and the possibility of mass electrocution, Honolulu Stadium was condemned and slated for demolition. With no alternate playing facility, the Islanders’ were forbidden from selling any tickets or advertising. The 1975 season was in jeopardy. Only on Opening Day did the Islanders reach a lease agreement with the State of Hawaii for the season.

What followed was nothing short of a miracle. Although the Islanders consistently fielded talented teams, exhaustive road trips usually relegated the club to a .500 record. In 1975, the Islanders overtook first place on May 7 and never looked back. Amid freezing rain in Salt Lake City on May 19, Gaspar scored three of the Islanders’ 19 runs as Gary Ross pitched a bizarre five inning perfect game against the Gulls.38 In another victory for Ross on June 22, Gaspar hit thrice in a 7-2 triumph over Tacoma 62. 39 He was the go-ahead run against Phoenix on July 8 as Jerry Turner belted him home on a first-inning triple.40 After his teammates were no-hit in the first game of a July 17 doubleheader, Gaspar homered in the nightcap in a 10-2 revenge victory.41 At the end of the regular season, Gaspar drove in 58 runs and hit .264 as the Islanders cruised to an 88-56 record to finish first in the West Division.42 Only months after facing removal from the league, the Islanders then triumphed over their rival Gulls to win the Pacific Coast League championship in six games.43

The Islanders were finally allowed to move to the cavernous Aloha Stadium in 1976, celebrating with another Pacific Coast League championship. Rod Gaspar set a personal record with five home runs, included two off David Clyde in a 19-1 decimation of the Sacramento Solons on May 5.44 He also enjoyed a 21-game hitting streak in May, lifting his batting average from .259 to .328.45 On August 18, Gaspar thrilled the Honolulu fans with yet another tiebreaking single as the threat of postponing the game by curfew was only minutes away.46 He ended the year batting 298. 47

Although Gaspar earned a place on the Pacific Coast League All-Star team, the outfielder was disappointed when the Padres did not recall him. Meanwhile, Roy Hartsfield was hired to manage the expansion franchise in Toronto. Although several Islanders players, including Chuck Hartenstein, were invited to train with the 1977 Blue Jays in Dunedin, Gaspar was not among them. Disappointed, he decided to retire from baseball. Years later, he asked Hartsfield why he was not drafted. Replied the manager, “I would have loved to draft you. You would have been my Opening day center fielder. Trouble was you were a National League player and I could only draft from the American League.”48 Hartsfield had control over only the expansion draft and not over other trades and purchases. Although Padres farmhands John Scott, Dave Roberts, and Dave Hilton joined the Blue Jays from Hawaii, their contracts were purchased in separate transactions.49

“I was 30 years old and had enough of the minor leagues. I was tired of the travel and fed up with the time away from my family. We had two kids under the age of five. I decided to retire and get a real job.”50 The Gaspars returned to California, settling in Mission Viejo with their children, Heather and Cade, and would later welcome sons Corte and David and daughter Taylor to the family. Yet it is one child in particular that occupies the forefront of Gaspar’s thoughts.

“I would like to talk about our fourth child, David Matthew Gaspar, a very talented and wonderful boy. He died of leukemia at the age of 9 in 1992. Obviously, it affected our family as well as many other people. For years, our other children would not talk about David in my presence. All the pictures of him were put away. They grew up in a state of fear, having seen death first hand. Obviously I was wrong in how I handled David’s death. My wife, Sheridan, is much tougher than I concerning this situation. She learned how to grieve, I didn’t. Over the last couple of years I have opened up my feelings concerning our boy. The pictures have returned, but even as I write this today I get sad. Hopefully I am coming across as a father who mishandled the death of his son, and not merely looking for sympathy. I wouldn’t want anybody to feel sorry for my situation.”51

Two years after the family tragedy, Cade followed in his father’s footsteps when he signed a professional contract with the Detroit Tigers. An excellent pitcher and shortstop at Pepperdine University, Cade was previously drafted by the Astros and the Yankees. In June 1994, the Tigers selected him as their first draft choice, signing him for $825,000. After posting a record of 1-3 with a 5.52 earned run average at Lakeland, the Tigers assigned him to a weight training program. Cade’s rapid muscle development forced him to change his delivery. Consequently, he hurt his arm. He was traded to the Padres in March 1996 and retired after one season at Rancho Cucamonga.52 The elder Gaspar remembers numerology playing a significant role in his son’s baseball career:

“Throughout his career, Cade always chose to wear one of two numbers. Number 17 was his dad’s number with the Mets, and number 3 was the Little League number worn by David Matthew Gaspar.”53

Rodney Earl Gaspar has been employed in the financial services industry since retiring as a player, specializing in asset management, insurance, and business planning. His children have provided him and Sheridan with ten grandchildren. Gaspar has won several national titles in handball – “the technique is the same as baseball.”54 Despite his numerous talents and complexities, Gaspar will always be remembered as a member of the Miracle Mets.

Twenty years after the celebration at Shea Stadium, Gaspar told Maury Allen that “there was something so special, so exciting about the 1969 team.”55 Three decades beyond, Gaspar continued to be reminded of the millions of fans who were enthralled by the accomplishments of his club. Included among the titles set to be released for the 50th anniversary of the Miracle Mets is Rod Gaspar: The Biography of a Miracle Met, co-authored with David Russell.

“As I’m sure all my teammates still get fan mail about that year, I do also. You can easily imagine that when people find out that I played for the 1969 World Champions and they see ‘the Ring,’ the atmosphere changes. What a wonderful baseball year.

What a great group of guys. We were the best.”56

Last revised: June 1, 2019

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “The Miracle Has Landed: The Amazin’ Story of how the 1969 Mets Shocked The World” (Maple Street Press, 2009), edited by Matthew Silverman and Ken Samelson.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-almanac.com, baseball-reference,com, and retrosheet.org.

The author would like to acknowledge and thank Dave Baldwin, Buzzie Bavasi, Clifford Blau, Craig Burley, Rod Gaspar, Sheridan Gaspar, Bill Gilbert, Paul Hirsch, Bruce Markusen, Kelly McNamee, Rod Nelson, Andrew North, John Pardon, Tito Rondon, and Dennis Van Langen.

Notes

1Maury Allen, After the Miracle: The Amazin’ Mets – Two Decades Later (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 208.

2 Harold Weissman, ed., New York Mets 1969 Official Year Book (Flushing, New York: The Metropolitan Baseball Club, Inc., 1969), 38.

3 Allen, 208.

4 Weissman (1969), 38.

5 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

6 Weissman (1969), 38.

7 Stanley Cohen, A Magic Summer (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988), 142.

8 Cohen, 142.

9 Ferd Borsch, “Hawaii Favorite Gaspar Reaching Bat Potential,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1973: 33.

10 Allen, 209.

11 Allen, 210.

12 Bruce Markusen, Tales From the Mets Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 2005), 40-41.

13 Markusen, 41.

14 Gene Schoor, Seaver (Chicago: Contemporary Books Inc., 1986), 139.

15 Allen, 211.

16 Markusen, 87.

17 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

18 Cohen, 142-143.

19 Interview with Emil J. Bavasi, September 27, 2007

20 Paul Cour, “Ollie, Going the Other Way, Finds Bright Path as Padre” in The Sporting News: April 17, 1971, 16.

21 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Team 38: 1970 Hawaii Islanders” on Minor League Baseball History: Top 100 Teams, 29 pars, [journal online]; available from http://web.minorleaguebaseball.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=38; Internet; accessed 25 October 2007.

22 Ferd Borsch, “A New Lease on Life – Boyer in Hawaii,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1971: 42.

23 Interview with Dave Baldwin, October 2, 2007.

24 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1971: 37.

25 Interview with Dave Baldwin, October 2, 2007.

26 Lloyd Johnson, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997), 510.

27 Jim Bouton, Ball Four: The Final Pitch, (North Egremont, MA: Bulldog Publishing, 2000), 135.

28 “Pacific Coast League” in The Sporting News: May 29, 1971, 40.

29 Ferd Borsch, “Hawaii Favorite Gaspar Reaching Bat Potential.”

30 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

31 “American Association” in The Sporting News: July 22, 1972, 38

32 “American Association” in The Sporting News: August 12, 1972, 34.

33 Ferd Borsch, “Hawaii Favorite Gaspar Reaching Bat Potential.”

34 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1974: 40.

35 Phil Collier, “McCovey Finding Home Run Range,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1974: 33.

36 Bob Eger, “Islanders to Wear PCL Crown in New Ballpark,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1975: 35.

37 Interview with Dave Baldwin, October 2, 2007.

38 Ray Herbat, “Ross Has Short Perfecto in Weirdo at Salt Lake,” The Sporting News: June 7, 1975: 40.

39 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1975: 33.

40 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1975: 32.

41 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, August 2, 1975: 34.

42 Bill Weiss, “Pacific Coast League Batting and Pitching Records,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1975: 33.

43 Johnson, 532.

44 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1976: 38.

45 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1976: 46.

46 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1976: 28.

47 Bill Weiss, “Pacific Coast League Batting and Pitching Records,” The Sporting News: September 25, 1976: 35.

48 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007

49 Louis Cauz, Baseball’s Back in Town: From the Don to the Blue Jays, A History of Baseball in Toronto (Toronto: Controlled Media Corporation, 1977), 190.

50 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

51 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

52 www.minors.baseball-reference.com

53 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

54 Interview with Rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.

55 Allen, 211-212.

56 Interview with rod Gaspar, September 25, 2007.