Greg Maddux – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

On August 26, 1995, Greg Maddux was at Wrigley Field in Chicago, formerly his home stadium. Now a member of the Atlanta Braves, Maddux was on the verge of tying a major-league record with his 16th consecutive road victory. With two out in the top of the third, Maddux singled to left, starting a five-run rally. He took the mound in the bottom of the inning with a 5-0 lead. In the press box, a writer muttered, “This is like giving a 15-0 lead to a regular human being.”1

On August 26, 1995, Greg Maddux was at Wrigley Field in Chicago, formerly his home stadium. Now a member of the Atlanta Braves, Maddux was on the verge of tying a major-league record with his 16th consecutive road victory. With two out in the top of the third, Maddux singled to left, starting a five-run rally. He took the mound in the bottom of the inning with a 5-0 lead. In the press box, a writer muttered, “This is like giving a 15-0 lead to a regular human being.”1

The comment reflected the dominance Maddux had established in the 1990s and the awe and wonder in which he was held as he reached the peak of his career. Maddux got his win in this game — and another five before the season closed. He became the first pitcher to win four consecutive Cy Young Awards. In 1994 and 1995, Maddux posted an earned-run average that was minuscule in any circumstances, historic in relation to the league ERA each year.

Gregory Alan Maddux was born April 14, 1966, in San Angelo, Texas, where his dad was stationed at the time. Dave Maddux had graduated from high school in Decatur County, Indiana, in 1957 and joined the US Air Force, where he was involved in accounting and finance for 22 years. When his girlfriend, Linda, graduated a year later, the couple was married.2 A daughter, Terri Lynn, was born in 1959 while Dave was stationed at Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage.

The family was at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, when son Mike was born in 1961. After two years in Taiwan, the Madduxes were stateside again when Greg was born. Soon after, with the Vietnam War going on, Dave had a one-year tour in Thailand. Linda took the kids back to Decatur County, where a number of family members lived.3

When Dave returned from Thailand, the transfers continued — to Minot, North Dakota, for a year; Riverside, California, for three years; and Spain for another three years. It was in Spain that the Maddux children were most active in sports. Terri was on the track team in high school and continued her love of running, including marathons, through her life. The boys participated in football. All three played basketball.

On the diamond, Terri, like most girls, was shunted away from baseball and into softball. Mike and Greg played in a sanctioned Little League. “Kids would come home from practice in the hot sun, and the first thing they would do is head outside into the yard to play more baseball in the hot sun,” Linda said. “Finally, I came to the realization that they were doing what they wanted to do. And they all survived.”

Dave Maddux got his final transfer in August 1976, to Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas. He eventually received orders to move back to Elmendorf Air Force Base. Linda recalled that once they would have embraced this assignment. “When we were kids we had decided we would want to go to Elmendorf to retire,” she said. “By this time, we had two kids in college, and we wouldn’t consider leaving them behind.”4 Instead, Dave retired from the military and became a poker dealer at various casinos in Las Vegas.

Terri was starting her junior year at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), at this time, and Mike was entering his first year at the University of Texas, El Paso. As for Greg, he found himself in a different school district from where his siblings had been, at Rancho High School, which had served those living at the military base. With Dave a civilian, the Madduxes moved to the southeast side of Las Vegas, and Greg attended Valley High School.

Greg played junior-varsity basketball, as Mike had done, but both brothers were discouraged from the sport by coaches, who wanted them to focus on their pitching potential in baseball. During Maddux’s junior year, Valley High School won the state baseball championship under coach Rodger Fairless.

Beyond what he learned from Fairless, Maddux had a tutor in Ralph Medar, a former scout, who oversaw workouts and organized pickup games on Sunday mornings in Las Vegas. “Ralph was the first pitching coach I ever had,” Maddux told John McMurray for an article in Baseball Digest. “He worked with me when I was 15 years old, and he taught me that movement was more important than velocity. He helped me make the ball move and sink as opposed to seeing how hard I could throw it. I think I was fortunate to learn that lesson at such a young age.”5

Maddux didn’t turn heads with out-of-this-world stuff, a blazing fastball or a 12-to-6 curveball. Never having had the luxury of such gifts, Maddux instead learned to pitch. Throughout his career, he was known for his control, late movement on his pitches, and knowing what he was doing. From an early age, Maddux established his reputation for being a cerebral pitcher, studying hitters and getting them out on pitches that hardly seemed imposing on their way to the plate — at least the first half of the way.

Maddux planned on attending the University of Arizona in Tucson and playing for Jerry Kindall, who had won two national championships as a coach and was on his way to a third. Linda remembers how impressed she was when meeting Kindall. “We had heard that Jerry took good care of his pitchers,” she said, adding that Kindall was known for being “not so intent on winning that he would burn out his pitchers.”6

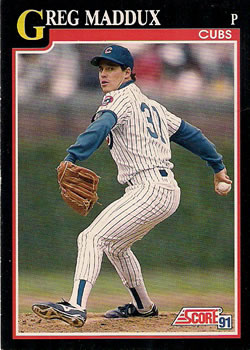

However, Maddux was drafted in the second round by the Chicago Cubs in June 1984, and the bonus offered was enough that two weeks later he decided to skip college and sign a pro contract. He put the bonus money aside, in case baseball didn’t work out and he wanted to go back to college, and lived off his minor-league salary in addition to money he had saved during summer jobs he worked at Sears and Wendy’s in Las Vegas.

Maddux progressed through the minors with the steady rhythm that defined his work on the mound: rookie league in 1984, Class A in 1985, and a three-level rise the following season, from Double-A to Triple-A to the majors as a September call-up.

Maddux made his major-league debut as a pinch-runner for the Cubs in the 17th inning of a game against Houston on September 3, a game that had started the day before and was suspended by darkness. He stayed in the game and pitched the 18th inning, giving up a run and taking the loss. Four days later, he was the starter against Cincinnati and went the distance in an 11-3 win, which stopped a seven-game Chicago losing streak.

Maddux made five starts for the Cubs in 1986, the last one at Philadelphia. The opposing starter was his brother Mike, who had also reached the majors that season. Greg prevailed in this game, winning 8-3.

Opponents in 1986, Greg and Mike became teammates for the first time after the 1987 season, playing winter ball in Maracaibo, Venezuela. The pitching coach was Dick Pole, who had worked with Greg in the minors and would again with the Cubs. Pole is often credited with teaching Maddux the value of a groundout. “Dick always told me. ‘You don’t have to strike him out, you just got to get him out,’” Maddux said.7

Pole was also discovering in Maddux a fearlessness on the mound, one that allowed him to throw any pitch in any situation. Pole said that when he was a pitching coach for other teams, he warned that Maddux would throw a changeup on a full count in the ninth. Invariably, however, batters would still get caught looking in these situations.8

Maddux had one more brief stint in the minors, in 1987, and then was up for good. He had a great start in 1988, earning a berth on the All-Star team, before cooling off. After a slow start in 1989, he picked it up. Combined, he had 37 wins and an ERA of 3.07 for the two years.

Maddux had one more brief stint in the minors, in 1987, and then was up for good. He had a great start in 1988, earning a berth on the All-Star team, before cooling off. After a slow start in 1989, he picked it up. Combined, he had 37 wins and an ERA of 3.07 for the two years.

In 1992, Maddux had 10 wins by early July and was picked for the All-Star Game, in which he relieved starter Tom Glavine of Atlanta, who had a 13-3 record and seemed on his way to a second consecutive Cy Young Award. However, Maddux was outstanding over the remainder of the year, finishing the season with a 2.18 ERA, third in the majors, and leading major-league pitchers with 268 innings pitched. Although Wins Above Replacement (WAR) was not yet in wide use, later analyses showed that Maddux led all players in 1992 with a WAR of 9.4 (9.2 as a pitcher).9 Maddux got the Cy Young Award, and Glavine finished second.

Maddux was a free agent after the 1992 season and was the top player on the market. His agent, Scott Boras, was negotiating with Cubs general manager Larry Himes and, characteristically, was expecting top dollar. The Cubs were offering a five-year contract for 27.5million(guaranteedwithanother27.5 million (guaranteed with another 27.5million(guaranteedwithanother1.5 million in incentives). When Maddux didn’t sign right away, the Cubs signed free agent Jose Guzman and appeared to back off on their offer to Maddux. The New York Yankees topped all offers to Maddux at 34million(reportedlyincreasedto34 million (reportedly increased to 34million(reportedlyincreasedto37.5 million10), and Maddux seemed ready to go to the Bronx. A late entry by Atlanta at $28 million caught his attention, and Maddux signed with the Braves.

Maddux had a few reasons for signing for less money than what he could have gotten from the Yankees, including that he thought Atlanta would be a better place to raise a family than New York. Maddux had married Kathy Ronnow, whom he had known since high school, in 1988. By the end of 1993, they had a daughter, Amanda Paige (who goes by Paige). In 1997 they had a son, Chase.

A player departing a team as a free agent often leaves hard feelings with fans, and Maddux was back at Wrigley Field for the season opener in 1993. He wasn’t fazed by the booing he received as the Braves won the game, 1-0, with Maddux outdueling the Cubs’ Mike Morgan (who was also a graduate of Valley High School in Las Vegas).

Although he understood the fans’ reaction, Maddux was hurt by comments made by former teammates, such as Ryne Sandberg, about his signing with the Braves. The charges included that he had planned to sign with the Braves all along and used the Cubs (and then the Yankees) to get a larger offer. Maddux said he made repeated calls to the Cubs during the final stage of negotiations and if the team would have put its original offer back on the table, he would have considered it “heavily.”11 (Unbeknownst to Maddux at the time of his final call, the Cubs had just signed free-agent Randy Myers. The Cubs had also signed another pitcher, Dan Plesac. According to Himes, “We went over the numbers on those,” meaning there wasn’t money left for Maddux.)12

What didn’t work out for the Cubs became a boon to the Braves. Maddux was eventually called by Houston general manager Gerry Hunsicker, “The greatest free-agent signing in baseball history.”

Atlanta pitching coach Leo Mazzone said, “When we signed Maddux, I didn’t realize at the time it was going to be the greatest free-agent signing in the history of the game. But I knew I was going to get a lot smarter, real quick.”13

Maddux was joining a team that had won the last two National League pennants with a rotation that had Glavine, a former and future Cy Young recipient; John Smoltz, a future Cy Young recipient; and another top young pitcher, lefthander Steve Avery. Not surprisingly, the Braves staff allowed the fewest runs in the National League in 1993. With a strong lineup — including shortstop Jeff Blauser and outfielders David Justice and Ron Gant — the Braves were near the top in runs scored, as well. The one team in their division to rival them in both categories, the San Francisco Giants, battled the Braves to the end. Maddux was the winning pitcher in the Braves’ penultimate game, and the next day Glavine was the winner while the Giants were losing. Atlanta, with 104 wins, beat out the Giants by a game for the title in the National League West.

Steve Avery started the first game of the playoffs, which the Braves lost to the Philadelphia Phillies in 10 innings. Maddux, fully rested for Game 2, pitched seven strong innings as the Braves tied the series. The Phillies won two of the next three, and the Braves faced elimination in Game 6, with Maddux back on the mound. This time he didn’t make it through the sixth, giving up six runs (five earned), and the Phillies won to advance to the World Series.

During the regular season, Maddux led the league with 267 innings and an ERA of 2.36 and received the Cy Young Award again. What was coming, however, was even better.

The 1994 and 1995 seasons were truncated by a players’ strike, and Maddux pitched barely over 200 innings, although it was enough to lead the majors both years. His ERA in 1994 was 1.56. Two years before, when Maddux received his first Cy Young Award, National League teams averaged 3.9 runs per game, and the league ERA was 3.50. In 1994, the averages were 4.6 and 4.21, respectively.

Maddux’s 1994 ERA was only 37.1 percent of the league average, even better than what Bob Gibson had achieved with his 1.12 ERA in 1968, the Year of the Pitcher. Maddux in 1995 had a 1.63 ERA, 39 percent of the league average.

Writers, analysts, and others were touting Maddux as the best right-handed pitcher since Walter Johnson. A number of outstanding southpaws pitched in the period between Johnson and Maddux — Lefty Grove, Warren Spahn, and Sandy Koufax, and pundits generally conceded that Maddux was not on the same level as Koufax.

Pitchers can be compared in many ways, and the difference in innings pitched then and later is relevant to any discussion about the greatest. In terms of ERA relative to the league average, Maddux has few rivals, including Koufax. In addition, the ballpark factors show Dodger Stadium — Koufax’s home park in his prime — to be pitcher friendlier than Maddux’s home parks with the Braves, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium and Turner Field.14

Maddux finished this four-year run of greatness by pitching in his first World Series. With seven days’ rest, he started the first game of the 1995 World Series and was outstanding. The first batter he faced, Cleveland’s Kenny Lofton, reached base on an error and came around to score. The only other baserunners off Maddux were Jim Thome, with a fifth-inning single, and Lofton, who singled in the ninth and came around to score on an error. Atlanta won the game, 3-2. Maddux had the chance to finish off the Series five days later but wasn’t as sharp. He gave up two runs in the last of the first. After the Braves tied the game, he gave up two more runs and took the loss. The Braves still won the series, taking the next game 1-0 on a David Justice home run and a one-hitter by Glavine and Mark Wohlers.

Maddux pitched in two more World Series. In Game 2 of the 1996 Series he pitched eight scoreless innings, allowing six hits and no walks, as the Braves beat the New York Yankees, 4-0. He was the losing pitcher in the final game as the Yankees won the World Series, 4 games to 2. In 1999 the Yankees beat the Braves again, this one a sweep. Maddux pitched the opening game and carried a 1-0 lead into the eighth inning before giving up four runs. His performance in five World Series games was good — he had a 2.09 ERA in those games. Between 1989 and 2008 Maddux appeared in 35 postseason games and had a 3.27 ERA in 198 innings.

As for the regular season, Maddux continued in top form although he didn’t receive any more Cy Young Awards. Between 1996 and 2000, he was in the top 5 in the balloting four times. His 1997 season was of the caliber that it would have been the best in the league in a lot of years. However, this year Pedro Martinez of Montreal was beginning a string of Maddux-like seasons.

Martinez, with the Expos and Boston Red Sox, received the Cy Young Award three times in four years, with a second-place finish the other year. In 2000 Martinez had a 1.74 ERA when the league average was 4.91, a performance even better than what Maddux had produced in 1994.

Martinez’s fantastic seasons served to highlight the dominance of Maddux around the same period. The pair had produced three of the top five performances in terms of ERA+ (the pitcher’s ERA compared to the league ERA with adjustments made for the pitcher’s home ballpark). The others in the top five had occurred in the Deadball Era (Dutch Leonard in 1914) and the 19th century (Tim Keefe in 1880).

Although Martinez was gone as a Cy Young rival after 1997, the National League continued to have strong contenders for the award. Maddux’s teammates received it in 1996 (Smoltz) and 1998 (Glavine); Randy Johnson of Arizona then started a string of four Cy Young Awards.

Maddux continued as a top pitcher into the 21st century, even if he was no longer a perennial contender for the Cy Young Award. He pitched with the Braves through 2003 before signing as a free agent with the Cubs before the 2004 season. Over the next few years he pitched for the Los Angeles Dodgers and San Diego Padres. Maddux’s last game was in relief for the Dodgers in the final game of the 2008 National League Championship Series. He pitched two innings and gave up two unearned runs as Philadelphia beat Los Angeles for the pennant. A free agent at the end of the season, Maddux called it a career, announcing his retirement in December.

Between traditional statistics, such as wins, and ones more recently embraced, such as ERA+, Maddux was outstanding both in peak and career value. Much is made of him winning at least 15 games a year between 1988 and 2004. He finished with 355 career wins, the most of any pitcher other than Warren Spahn who had pitched after 1930.

Maddux struck out 3,371 batters in 5,008 1/3 innings, an average of about 6 per 9 innings. Although this may not raise eyebrows, a key to his success was his control — he walked just 999 batters, an average of 1.8 per 9 innings. In 2001 Maddux set a National League record with 72 1/3 straight innings without a walk, a streak that was broken with an intentional walk. During his Cy Young Award seasons, Maddux led the National League in Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) all four years.15

Bob Nightengale of USA Today pointed out how Maddux had dominated the game for years without being a power pitcher: “Maddux, whose fastball is routinely clocked at only 88 mph, remarkably throws more fastballs than any established pitcher in the game. The difference is control and movement. He can throw the fastball with nearly pinpoint control, while the ball darts and spins as if he’s controlling it like a yo-yo.”16

“He can throw you a strike and still not give you anything good to hit,” said Braves pitching coach Leo Mazzone. “He’s a master at that. It’s the greatest command I’ve ever seen on a consistent basis.”17

Mazzone and others have told of Maddux’s penchant for telling his pitching coach, manager, and teammates about how he will get out of an inning, such as saying that he’ll get the batter to foul out to the third baseman on the second pitch to him.18

Jeff Torborg, who caught flamethrowers Sandy Koufax and Nolan Ryan, later observed and marveled at Maddux carving up batters in a completely different manner. Torborg commented on how Maddux could throw a pitch so that it appeared it would be a ball but then break over the plate after the batter had decided not to swing. Torborg said Maddux stood out because, unlike most pitchers, he could start the ball out on either side of the plate and have it break back for a strike.19

Maddux summed up his style in an interview with Bob Nightengale in 2001:

“The best pitch in baseball is a located fastball. That will always be the best pitch. You can set up everything you want off that.

“[Hall of Fame pitcher] Don Sutton used to always say to make sure all your pitches look the same when they’re 5 feet out of your hand. Then find ways to make the ball end up in different places and at different speeds. The more ways you can put it in more places at more speeds, the better.

“That’s pitching.”20

However the stats are sliced, Maddux stands out as one of the best pitchers ever, and he was easily elected to the Hall of Fame in 2014. He was inducted with his teammate, Tom Glavine, and his manager while with the Braves, Bobby Cox. His number 31 was retired by both the Braves and the Cubs (with the latter, the retirement of 31 is for both Maddux and Ferguson Jenkins).

The Madduxes made Las Vegas their permanent home, even as Greg moved around the majors as a pitcher and later in assorted duties with teams. He worked with the Cubs as an assistant to the general manager, focusing on working with pitchers from 2010 to 2012. He then worked with the Texas Rangers, where brother Mike was the pitching coach, and later as a special assistant with the Los Angeles Dodgers. In between he was the pitching coach for the United States in the 2013 World Baseball Classic.

His son, Chase, made it as a right-handed pitcher on the UNLV baseball team, and in 2016 Greg joined the Rebels as a volunteer assistant coach.21

In 1995, when Maddux was at his peak, Tom Verducci wrote in Sports Illustrated, “His career is a masterpiece, available for all to see every fifth day or so as he works atop the pitching mounds of National League ballparks.

“The rest of us, should we recognize our good fortune, could be eyewitnesses to genius. Did you see van Gogh paint? No, you could respond, but I saw Greg Maddux pitch.”22

Last revised: March 14, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Overheard by the author of this article, who was in the press box that Saturday afternoon.

2 The information on the Madduxes and the details of their children growing up came from a telephone interview between the author and Linda Maddux, May 16, 1995.

3 Dave was one of 10 children, three of them boys. Linda was one of three girls.

4 Telephone interview with Linda Maddux, May 16, 1995.

5 John McMurray, “Greg Maddux: Consistency, Hard Work, and Pitching Smarts Made Him a Winner,” Baseball Digest, September 2007: 40.

6 Telephone interview with Linda Maddux, May 16, 1995.

7 Carroll Rogers Walton, “More to Maddux Than Meets the Eye,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 17, 2009, accessed February 23, 2018 from https://www.ajc.com/sports/baseball/more-maddux-than-meets-the-eye/BnbkvNMtw2oN4vErpjatCI/.

8 Carrie Muskat, “Like Clockwork: In-out, Up-down,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 21-25, 1995: 20.

9 baseball-reference.com is the source for WAR. Maddux probably received a little bump in his WAR for his fielding; he received the Gold Glove for the third time in 1992, and he got the award 18 times in his career.

10 Joey Reaves, “Maddux and Dawson Sign Off,” Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1992: 3, Section 4.

11 Alan Solomon, “Hurt, Maddux Answers Critics,” Chicago Tribune, December 13, 1992: 16, Section 3.

12 Alan Solomon, “Maddux Agent Tried Cubs Again,” Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1992: 3, Section 4.

13 Bob Nightengale, “Inside the Mind of Maddux,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 15-21, 2001: 14.

14 baseball-reference.com has Maddux with an ERA+ (the pitcher’s ERA relative to the league ERA, is adjusted to the pitcher’s home park) of 271 in 1994 and 260 in 1995. Koufax, Spahn, and Grove never approached those figures.

15 FIP focuses on elements of pitching — walks, hit batters, home runs, and strikeouts — that are independent of fielding.

16 Bob Nightengale, “Inside the Mind of Maddux,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 15-21, 2001: 14.

17 Carrie Muskat, “Like Clockwork: In-out, Up-down,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 21-25, 1995: 22.

18 These stories emerged during a player panel — moderated by Pete Van Wieren with panelists Phil Niekro, Mark Lemke, Bobby Cox, and Ron Gant — at the SABR convention in Atlanta, August 6, 2010.

19 Murray Chass, “Koufax and Maddux: Unequaled Mastery,” The New York Times, August 17, 1997: 24.

20 Bob Nightengale, “Inside the Mind of Maddux,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 15-21, 2001: 14.

21 “Baseball Hall of Famer Joins Rebel Staff,” UNLV Rebels press release, July 6, 2016, http://www.unlvrebels.com/sports/m-basebl/spec-rel/070616aaa.html.

22 Tom Verducci, “Once in a Lifetime,” Sports Illustrated, August 14, 1995: 24.