Rich Gedman – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

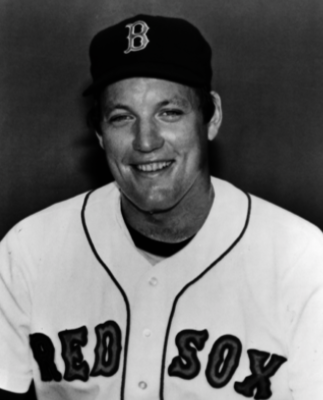

Richard Leo Gedman fulfilled his childhood dream in his tenure in the major leagues, suiting up for over a decade for the team he grew up rooting for. Gedman, a native of Worcester, Massachusetts, spent parts of 11 seasons (1980-1990) as a catcher for the Boston Red Sox. The two-time All-Star also played for the Houston Astros and St. Louis Cardinals in his 13-year career.

Richard Leo Gedman fulfilled his childhood dream in his tenure in the major leagues, suiting up for over a decade for the team he grew up rooting for. Gedman, a native of Worcester, Massachusetts, spent parts of 11 seasons (1980-1990) as a catcher for the Boston Red Sox. The two-time All-Star also played for the Houston Astros and St. Louis Cardinals in his 13-year career.

Born on September 26, 1959, Gedman was the middle of five children. He grew up with two brothers and two sisters – the children of Martha Gedman, a homemaker, and Richard Gedman Sr., a truck driver for the Atlas Distributing Company before an injury forced him into early retirement. He also spent time as a semiprofessional bowler. He died in 1986 at the age of 55. Martha Gedman died in 2005.

Losing his father at the start of the 1986 season was crushing for Gedman, who told Stan Grossfeld of the Boston Globe that he cried before every World Series game against the New York Mets. “… (B)efore every game I wanted to make sure I thought of him,” Gedman told Grossfeld. “So as the national anthem was playing, tears would be welling up. It’s a pretty emotional time, that separation of thought there that he was there with me even though he wasn’t there. He was watching me play.”1

Playing as a first baseman and pitcher, Gedman led St. Peter-Marian, a Catholic high school in Worcester, to a state baseball championship in 1977. He met his future wife, Sherry Aselton, at St. Peter-Marian that year. (They were married in 1982, and have lived in Framingham, Massachusetts, ever since.)2 Sherry was an athlete herself, dominating on the mound in softball and earning a full scholarship to the University of Connecticut. Rich went undrafted in the June 1977 major-league draft, but the 17-year-old was signed by the Red Sox on August 5.

The father of three gifted athletes, Gedman attributed much of his baseball success to the late Bill Enos, a scout for the Red Sox, who in 1977 recognized the teenage slugger’s talent. Enos liked Gedman’s batting, but was concerned about his defense.3 Gedman’s lackluster speed made him a liability as an outfielder and he was subpar at first base. Enos recommended that Gedman make a permanent transition to catcher, a position he mastered playing in Boston’s farm system.

Gedman’s journey through the minors began in 1978 for the Class-A Winter Haven Red Sox of the Florida State League. In 98 games Gedman batted a team-best .300. In the offseason he worked two jobs, in a newspaper mailroom and on a brewery loading dock. He maintained these jobs during the offseason until he got the eventual call-up to the majors.

After an impressive showing for Winter Haven, Gedman was promoted in 1979 to the Double-A Bristol Red Sox (Eastern League). There he showed some power, hitting .274 with 12 home runs, 25 doubles, and 63 RBIs in 130 games.

The next year Gedman was moved up to Triple-A Pawtucket. He led all International League catchers in assists and double plays. In 111 games played, he clubbed 11 homers, though his batting average fell to .236. A September call-up, the 20-year-old Gedman made his major-league debut on September 7 at Fenway Park against the Seattle Mariners. He pinch-hit for Carl Yastrzemski in the third inning, flied out to center field against Byron McLaughlin, and replaced Yastrzemski as the designated hitter. In the fifth Gedman singled to right field off McLaughlin for his first major-league hit. He singled again in the seventh and scored his first major-league run on Garry Hancock’s three-run homer. Gedman popped out to third base in his final at-bat of the Red Sox’ 12-6 loss, finishing 2-for-4 in his major-league debut.

On September 17 Gedman made his first major-league start, at home against Cleveland. The DH that day, he went 1-for-5 in Boston’s 6-5 loss. His first start as a catcher, on the 26th, was auspicious: Gedman was behind the plate for a one-hitter pitched by Dennis Eckersley, a 3-1 victory over the Toronto Blue Jays in Toronto, and drove in a run with a single. For the abbreviated season, Gedman hit .208 in 24 at-bats.

Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk signed with the Chicago White Sox in the offseason. Eventually Gedman would replace him, but he started the 1981 season at Pawtucket and played in one of the minor leagues’ most fabled games, the 33-inning contest between Pawtucket and Rochester that began on April 18. The starting catcher, Gedman caught the first nine innings, going for 1-for-3, before being lifted for a pinch-hitter. The game was suspended after the 32nd inning. When it resumed on June 23, the Red Sox won it in the 33rd.4

Gedman was called up to the Red Sox in mid-May after catcher Gary Allenson went on the disabled list. Seizing the opportunity, Gedman batted .288 with 5 homers and 26 RBIs in 62 games of the strike-shortened season. He finished second in the baseball writers’ American League Rookie of the Year voting, but was named AL Rookie Player of the Year by The Sporting News.

As he shared the catching duties with Allenson in 1982, Gedman’s batting average dipped to .249. In 1983 he got only 53 starts as he continued to split time with Allenson. He lifted his batting average to .294, though he collected just 19 extra-base hits (two homers). After the season Gedman played winter ball in Venezuela, appearing in 60 contests.

The inclusion of winter ball, along with the strong relationship he built with new hitting coach Walt Hriniak, laid the foundation for a career year for Gedman in 1984. Not only did he belt a career-best 24 home runs that season, he also established himself as the everyday catcher for the Red Sox. He batted .269 with 72 RBIs. Gedman sustained his success in 1985, registering career highs in batting average (.295), hits (147), doubles (30), triples (5), runs scored (66), walks (50), and RBIs (80). He was named to the American League All-Star team for the first time (he struck out in his only at-bat), led all catchers in assists, and threw out 53 of 122 would-be basestealers (43 percent). On September 18, in a 13-1 victory over Toronto at Fenway Park, he hit for the cycle and drove in a career-high seven runs.

In the pennant-winning 1986 season Gedman set an American League record for putouts by a catcher with 20, as Roger Clemens set a record with 20 strikeouts in a game against the Seattle Mariners. The next day Gedman collected 16 putouts (eight strikeouts from starter Bruce Hurst) for a total of 36 in two games – the most ever by a catcher in consecutive days. He finished the season with a league-high 866 putouts. Gedman earned his second straight All-Star selection (he caught the last two innings of the American League’s 3-2 victory).

The 1986 American League Championship Series between the Red Sox and the California Angels was arguably the pinnacle of Gedman’s career. The Red Sox fell behind in the best-of-seven series, three games to one. Hosting Game Five, the Angels were an inning away from a trip to the first World Series in their history. Gedman had batted the Red Sox to an early lead with a two-run homer off Angels ace Mike Witt in the second inning. But the Red Sox trailed 5-2 entering the ninth. Witt was two outs away from a complete game before the Red Sox engineered a dramatic rally. Don Baylor pulled Boston to within a run, 5-4, with a two-run home run. With Gedman coming up, Angels manager Gene Mauch lifted Witt. Gedman had been 3-for-3 off Witt. Reliever Gary Lucas was unable to close out the game. He hit Gedman with his first pitch of the at-bat and then surrendered a towering two-run homer to Dave Henderson.

The Red Sox could not sustain their 6-5 lead, however, and needed extra innings to capture the road victory. Boston scored the eventual winning run in the top of the 11th, and Gedman played a role in getting the run home. With runners on first and second, he laid down a perfectly placed bunt to third for a single. Baylor, who advanced to third on Gedman’s bunt, came around to score on Henderson’s sacrifice fly. Gedman finished the win 4-for-4 at the plate with a homer, two runs scored, and two runs batted in. He also threw out two runners on the basepaths.

With the Red Sox down three games to two and the series shifting back to Boston, the Red Sox captured Games Six and Seven to advance to the World Series against the New York Mets.

The Series brought great frustration to Gedman and Red Sox Nation. Gedman became a scapegoat in perhaps the most devastating loss in franchise history. The Red Sox led the Mets, three games to two and, in the 10th inning of Game Six, led by two runs and were within an out of capturing their first World Series title in 68 years. But the Mets got consecutive singles by Gary Carter, Kevin Mitchell, and Ray Knight to come to within a run. With Kevin Mitchell on third and Mookie Wilson at bat, Red Sox reliever Bob Stanley threw a pitch that Gedman failed to corral. The official scorer called it a wild pitch, but much of Red Sox Nation viewed it as a passed ball, and felt that while the pitch was uncatchable, Gedman could have at least blocked the ball.

Mitchell scored on the wild pitch, tying the game, and the Mets won when Wilson’s grounder went between Bill Buckner’s legs. The Mets then won Game Seven to secure the second World Series championship.

Gedman’s career spiraled downward after Boston’s crushing defeat. After the World Series ended, he was set to join other major leaguers in a seven-game exhibition series in Tokyo. Gedman, though, was unable to participate in the series after fracturing his cheekbone while warming up Detroit Tigers pitcher Willie Hernández.5

As the calendar flipped to 1987, a banged-up Gedman had a bigger issue to worry about – he was a free agent. Despite his All-Star Game appearances in each of the prior two seasons, the Red Sox were leery of giving Gedman the lengthy contract extension he desired. The Red Sox had concerns, in part because of Gedman’s injury. His mental strength was also a new concern, as Boston’s brass knew he would field incessant questions from the media as to whether Stanley’s wild pitch was actually a passed ball. The two sides eventually agreed to terms, but Gedman could not return to the Red Sox until May 1 because of a free agency rule in the Collective Bargaining Agreement.6

Behind the eight-ball for the season, Gedman suffered a dismal year in 1987. He hit just .205 with one home run in 151 at-bats. Gedman tore a ligament at the base of his left thumb in a home-plate collision with Jesse Barfield of the Toronto Blue Jays on July 27, ending his season prematurely.7

After rehabbing in the offseason, Gedman returned to the Red Sox – now sharing the catching duties with Rick Cerone. The two split time behind the plate in each of the next two seasons with Gedman hitting .231 and .212 in 1988 and 1989, respectively. The Red Sox, in need of hitting help at catcher, signed All-Star Tony Peña before the 1990 season. The writing was on the wall for Gedman, and he was traded on June 7 to the Houston Astros in a conditional deal after playing in just 10 games for the Red Sox that season.

In 40 games for the Astros in 1990, Gedman hit .202 with one homer and 10 RBIs. The Astros declined to re-sign him in the offseason. Gedman signed a two-year deal with St. Louis, for whom he served as the backup to Tom Pagnozzi. A shell of his former All-Star talent, Gedman batted a woeful .101 in 46 games in 1991. The 1992 season turned out to be his last in the major leagues. He batted .219 in 105 at-bats spanning 41 games. Gedman got the starting nod in the Cardinals’ season finale, against the Philadelphia Phillies at Busch Stadium. In his last major-league contest, he went 2-for-4 with an RBI and a run scored in the Cardinals’ 6-3 triumph over the Phillies.

The Oakland Athletics signed Gedman in January 1993. He spent most of spring training with the A’s, but was released before Opening Day. Gedman signed a minor-league contract with the New York Yankees in hopes of eventually being called up. But he never got a call-up and spent the entire year with Triple-A Columbus, batting .262 with 12 home runs and 35 RBIs in 89 games.

Gedman made one last attempt at returning to the majors the next year, signing with the Baltimore Orioles. He failed to make the major-league roster and was assigned to Triple-A Rochester. Rather than play a second straight year in the minors with little chance of being called up, Gedman retired.

In 13 major-league seasons, Gedman batted .252 with 88 home runs and 382 RBIs. He tasted playoff action in 1986 and 1988 with the Red Sox. In 18 postseason games, he hit .292 with 3 home runs and 8 RBIs.

Gedman coached in the independent leagues, and in 2005 he became the manager of the Worcester Tornadoes of the Canadian American Association.8 He managed the Tornadoes for six seasons (2005-2010), before rejoining the Red Sox organization in 2011 as the hitting coach for the Lowell Spinners. He got a chance to coach his son Matthew that year, before moving up the coaching ladder to Class A in 2012 as the hitting coach for the Salem Red Sox.9 Gedman was promoted to Double-A the next season as the hitting coach for the Portland Sea Dogs.10 In 2015 he was the hitting coach for the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox.

The Gedmans’ three children, sons Michael and Matt and daughter Marissa, all enjoyed success in athletics. Michael played college baseball at Le Moyne College in his freshman year, before transferring to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where he spent the final three years of his collegiate career.11 The first baseman batted .312 in three seasons with the Minutemen, graduating in 2010. Marissa was a defender on the women’s ice hockey squad at Harvard, where in 2015 she was a senior.12 Matt went to UMass, where he played shortstop for the Minutemen from 2008 to 2011. After a stellar senior season, in which he led the Atlantic-10 with a .402 batting average, he was drafted by the Red Sox in the 45th round of the 2011 MLB Draft.13

Notes

1 Boston Globe, March 3, 2014.

2 Boston.com, July 4, 2010.

3 Chaz Scoggins, Game of My Life; Memorable Stories of Red Sox Baseball (New York: Sports Publishing, 2006), 180.

4 New York Times, June 24, 2006. See also Dan Barry, Bottom of the 33rd: Hope, Redemption, and Baseball’s Longest Game (New York: Harper, 2012).

5 Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, November 3, 1986.

6 Associated Press, April 18, 1987.

7 New York Times, August 4, 1987.

8 Portland (Maine) Press Herald, January 27, 2013.

9 MassLive.com, August 25, 2012.

10 Bangor (Maine) Daily News, March 25, 2013.

11 Umassathletics.com, April 1, 2010.

12 <gocrimson.com/sports/wice/2013-14/bios/gedman%5Fmarissa>.

13 ESPNBoston.com, June 9, 2011.