Alfredo Kraus Interview by Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

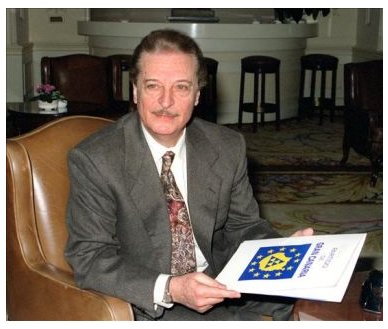

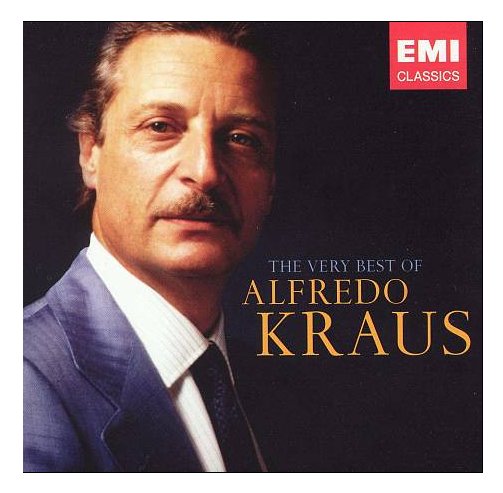

Tenor Alfredo Kraus

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Alfredo Kraus at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1962 - Elisir d'amore[American Debut] with Adani, Zanasi, Corena; Cillario

1963 - Barber of Seville withBerganza, Zanasi, Christoff, Corena; Cillario

Don Pasquale with Adani, Bruscantini, Corena; Cillario

1964 - Favorita withCossotto, Bruscantini, Vinco; Cillario

Don Giovanni with Stich-Randall, Curtin, Ghiaurov, Kunz, Uppman; Krips, Zeffirelli (set designer)

1965 - [Opening Night] Mefistofelewith Ghiaurov, Tebaldi, Suliotis; Sanzogno

Carmina Burana with Martelli, Bruscantini; Fournet

L'Heure Espagnol with Berganza, Bruscantini; Fournet

Rigoletto with Scotto,MacNeil/Bruscantini, Vinco; Bartoletti

1966 - Pearl Fishers with Eda-Pierre, Bruscantini, Ghiuselev; Fournet

Italian Flood Relief Benefit Concert

Traviata with Maliponte/Rinaldi, Bruscantini; Rossi

[Note: There was no Lyric Opera Season in 1967]

1968 - Don Pasquale with Grist, Evans/Washington, Bruscantini; Bartoletti

1969 - Puritani with Rinaldi, Cappuccilli, Washington; Ceccato

Don Giovanni with Watson, Ligabue, Gobbi, Evans, Raskin;Leitner, Gobbi (director)

1971 - Rigoletto with Robinson, Cappuccilli, Vinco; Bartoletti

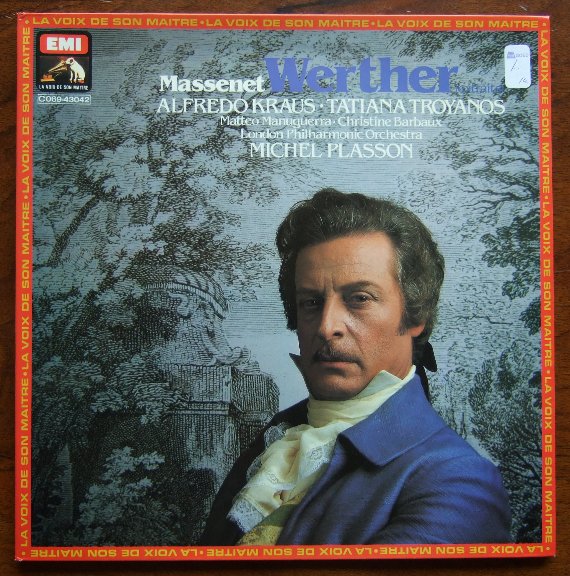

Werther with Troyanos, Angot; Fournet, Mansouri(director)

1973 - Manon with Zylis-Gara,Patrick,Gramm; Fournet

Daughter of the Regiment with Sutherland, Malas, Resnik, Tourel; Bonynge

1974 - Favorita with Cossotto, Cappuccilli, Vinco; Rescigno

Don Pasquale with Cotrubas, Ganzarolli, Sardinero; Bartoletti

1975 - Traviata with Cotrubas, Cappuccilli; Bartoletti

1976 - Rigoletto with Mauti-Nunziata, Mittelmann/Manuguerra; Chailly

1978 - Werther with Minton, Nolen; Giovaninetti

Don Pasquale with Blegen, Evans,Stillwell;Pritchard

1979 - [Opening Night] Faustwith Freni, Ghiaurov, Stillwell; Prȇtre

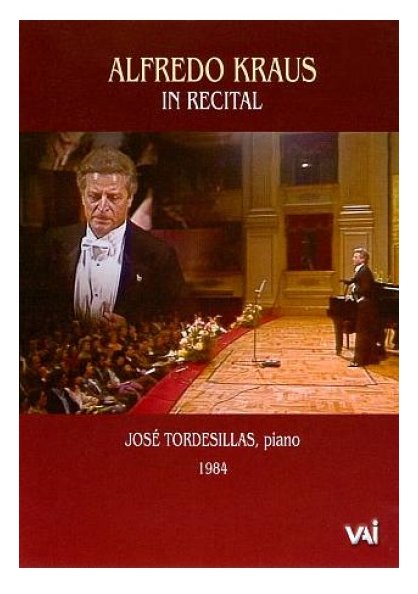

1980 - Recital

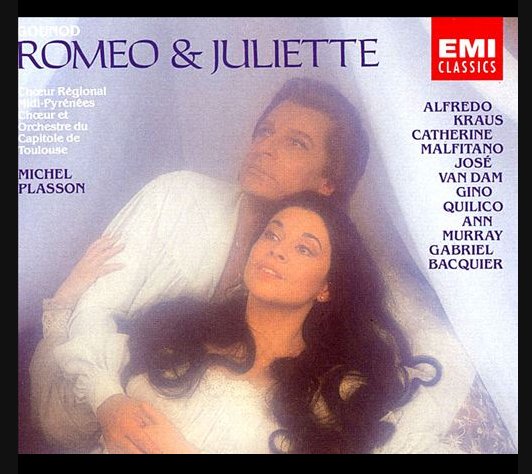

1981 - Romeo and Juliettewith Freni, Raftery, Bruscantini; Fournet

1982 - [Opening Night] Tales of Hoffmann with Welting,Zschau, Masterson, Mittelmann; Bartoletti

1983 - Manon with Scotto, Titus, Washington; Rudel

Callas Celebration Concert with Cotrubas, Scotto, Vickers; Bartoletti

-- Note: Names which are links refer to interviews by Bruce Duffie elsewhere on this website.

As can be seen in the chart above, Alfredo Kraus was a very important member of the Lyric Opera family for twenty-one years. He made his American Debut here and returned in season after season in various roles.

In 1981, he generously allowed me to visit him at his apartment for an interview. Gracious and elegant, his offstage deportment equalled or even surpassed his onstage presence. Quiet and charming throughout, he responded to my questions and offered his opinions about each topic.

Knowing that the first use of the material would be in the Massenet Newsletter, that is where we began our conversation . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let's start by talking a bit about Massenet. How is singing Massenet different from singing other composers?

Alfredo Kraus: In general, French opera is little different from Italian opera. Massenet is a very romantic composer, and sometimes his music is for the singers and at the same time in many parts of the opera he's for the orchestra. For that reason, it's very difficult to conduct. In general, at least in the operas I've sung, the character of the tenor is romantic, very lyric, but at the same moment the orchestra has a more dramatic character sometimes. If the dramatist is going through an exultation of the romantic part of the role, the orchestra could get very, very heavy, and if the conductor doesn't pay attention, he could cover the singers, sometimes.

Alfredo Kraus: In general, French opera is little different from Italian opera. Massenet is a very romantic composer, and sometimes his music is for the singers and at the same time in many parts of the opera he's for the orchestra. For that reason, it's very difficult to conduct. In general, at least in the operas I've sung, the character of the tenor is romantic, very lyric, but at the same moment the orchestra has a more dramatic character sometimes. If the dramatist is going through an exultation of the romantic part of the role, the orchestra could get very, very heavy, and if the conductor doesn't pay attention, he could cover the singers, sometimes.

BD: Is this more so than the Italian composers?

AK: Not more than Italian. In Italy it's easier because when the whole opera is dramatic you employ a dramatic tenor, or if the whole opera is lyric you employ a lyric tenor. The problem is a little less important, but in Massenet -- at least in the two opera we are talking about, Manon and Werther -- sometimes you think almost that you will need two tenors to sing the different acts. I don't think he wanted two different voices, he wanted probably the same voice with a heavier character in the expression, but going through dramatic and romantic styles, not heroic. This is the difference. When you sing, and more important when you conduct, you have to think that you are working with a light, lyric tenor voice.

BD: In an interview I had with Michel Plasson, he mentioned that the orchestration of Massenet was written very well for the voice. He says that it doesn't cover the voice. Is he mistaken?

AK: It doesn't cover if the conductor knows what could happen if he doesn't pay attention. At some moments you have the sensation that you will need a very heavy voice more than the one you heard at other moments. For instance, in Manonyou have the famous dream where you would need a very very light voiced tenor. But in the second aria, in St. Sulpice, you will need almost a dramatic tenor. Then the orchestra has to be a little softer than maybe you would desire. You are hearing beautiful dramatic music and your inclinations are to give more, and instead you have to think about giving a little less to help the tenor at that moment.

BD: Is it the same for the soprano?

AK: I think so. This is almost the same because even in the duets sometimes, if the sensitivity of the conductor is the same then it's easier because he knows that the author wanted the dramatic, romantic music.

BD: Have you sung any other Massenet besides these two?

AK: No. Massenet has beautiful operas, but for Le Cid you need a heroic tenor.

BD: Let's talk about these two characters. Tell me a bit about Des Grieux. Is he a simple man, a straightforward man? Is he humble? What is he like?

AK: I think that he is a simple man from the high bureaucracy maybe. His father has a very big influence on him, and I think also his character was not very strong.

BD: Doesn't it take a strong character to go with Manon?

AK: No, because in the whole opera he is doing what others want him to do. He has a big reaction but the reasons were also very very strong. When Manon abandons him he goes to be a priest, but the first time she arrives to convince him he couldn't resist her. In the whole opera he's a man conducted by all the other people.

BD: Is he a puppet?

AK: Not really, but he couldn't resist her.

BD: So he's a weak character then?

AK: Yes, I think so. Werther is just the opposite. He has a strong, big character. He has a big influence on Charlotte. He forces her to do things.

AK: Yes, I think so. Werther is just the opposite. He has a strong, big character. He has a big influence on Charlotte. He forces her to do things.

BD: Do you think Werther and Charlotte would have been happy if they had gotten together?

AK: Probably not. Werther was a poet with his head in the skies the whole time, and she was a very practical woman. Her life was for children, for the house, to be a good housekeeper and everything. Probably they could balance each other, but I don't think so. Probably later Werther would realize that she wasn't the ideal woman for his poetry. I'm not sure . . .

BD: Is there any woman that could come up to Werther's ideal?

AK: Theoretically, yes. But you never know in the world if it would happen.

BD: Continuing this game of speculation, is Charlotte happy with Albert or is she just doing her duty?

AK: She is doing her duty. At the same time she found the balance she wanted to have

— a nice home, children, enough money to have a bureaucratic life in a small village. From this side she was happy, or thought she was.

BD: She was content?

AK: Yes. But at the same time, she was thinking the whole time about the kind of different life she could have had with Werther. It was a fantasy for her. It was kind of mysterious for her, and it's at that moment of her life she realized that she would lose something very important or very different. Then there was a kind of curiosity in this attraction with Werther.

BD: When she leaves Albert to come to Werther at the end, is she leaving Albert for good or just to comfort Werther a little bit and then return home?

AK: It was very difficult to know what happened. She didn't know. She had the impression something bad, something terrible would happen, but she ran to Werther's house to be sure, to see what happened.

BD: To be sure that he's dead?

AK: Yes. She had the premonition and she wanted to know if it was true. But at the same time she was afraid because otherwise, for her, it would be a terrible dilemma to go and find nothing has happened. She would not know what to say to him.

BD: Suppose he had just shot himself in the shoulder.

AK: Or maybe nothing. Perhaps he had gotten the pistols for the trip as he had told her. Then she would arrive and not know what to tell him. It would be terrible for her if nothing had happened, but she didn't think about the consequences. She only wanted to know what did happen.

BD: In a way she's impulsive.

AK: Oh yes, very.

BD: But her home life with Albert would seem to contradict that.

AK: In different ways they were very morose people. He was thinking about death from the first moment

— even when he was happy. In your mind you think about it, but even in the happy moments he was sad. The beauty of the world had a negative influence on him. He admired the beauty, but at the same time he was sad about everything. It's a strange kind of existence to be a poet. She knew from the first moment because he said at their first meeting that he will die if she doesn't love him. Then in the second act, again he said the same thing. She knew it, but at the same time she was curious to know if this man could maintain his promise to kill himself for her.

BD: Did it take strength on his part to commit suicide?

AK: Oh yes. She is also a very strong woman and very intelligent, and she knew the end but she wanted to go and see it, to watch it and see what happened.

BD: Was she disappointed that it happened?

AK: She was probably disappointed because she thought that she was losing something very important. At the same time, she arrived at the end of something that she was thinking the whole time.

BD: How important is Werther to Charlotte?

BD: How important is Werther to Charlotte?

AK: It is important because you must understand that everybody has a normal life and a different interior life, a fantasy life. Werther for her was the fantasy, the different kind of life, very different from the circumscript kind of life she was leading. Werther, for her, was something out of this world.

BD: This was exciting for her?

AK: Exciting her curiosity, something that could happen but never will.

BD: So for each the other one is the dream.

AK: Yes. But at this moment, what would she prefer

— fantasy or reality? She chose the real life, but she kept the fantasy very close to her because it was a part of her to realize herself in one way in her mind.

BD: How does Albert take all of this?

AK: Albert is very difficult to say because in the opera he is not a very developed character. He is just a nice man from the bureaucracy also, a good, strong position.

BD: He seems to put up with a lot.

AK: He loves her very much and he was strong. Don't forget that Charlotte's mother wanted him to marry her, so he was very sure of the situation. He didn't think that anything could happen between Charlotte and Werther. It was only at the end of the second act when Sophie is crying saying that Werther is leaving forever does he (Albert) realize that Charlotte had feelings about Werther. It is very difficult to say how he really was, what kind of man he was. He was strong, very cold, saw everything from a high position as though he were a king or something.

BD: He was the king of his household.

AK: Yes.

BD: Do you enjoy these two Massenet parts? Are they special for you?

AK: I like better Werther because he is more complex. Des Grieux is lighter and you don't go so deep into him. You don't need it. It is more superficial.

BD: You're going to make a recording of Manon?

AK: Yes, with Cotrubas and Plasson. [Also in the cast is José van Dam, and the Vocal Coach is Janine Reiss, who speaks specifically about Kraus.]

BD: Do you like making recordings?

AK: No, I don't.

BD: [Somewhat surprised] Why?

AK: Many reasons. First of all, I think that the record is a document, and I am never very happy about recordings of myself singing. I think that if you have to have a document, you have to be perfect. Everything has to be perfect

— the orchestra, the conductor, the other singers.

BD: The balance?

AK: The balance in terms of sound, but I'm talking also about feeling. The whole opera has to live, and this is very difficult to obtain by recording the same results about feeling that you can have in the live performance.

BD: Do you think a record should be made from a live performance?

AK: I think so, and probably will be so in the future because now with the pirate records, millions of people think like me and they prefer it. Even if the sound is not perfect, they prefer something with live performance.

BD: There is more heart?

AK: More heart, yes. You go through the opera in the right way

— from the beginning to the end. Also there is a communication between the audience and the stage that you don't get in a studio record.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You can't communicate with the producer?

AK: No. The producer is in another room and you have in between this metal thing called a microphone. It's terrible because you are working with the terror that something is wrong. There might be a small sound or a little thing in your voice... noises... mistakes. It is working with tension because you know you have to repeat, and that takes more time and you feel more tired and it's more money. It's impossible to work that way.

BD: There is too much pressure?

AK: Yes.

BD: Then why do you do the recordings? Why don't you just say no?

AK: For many years I said no, but I had also many people pressuring me, pushing, saying you have to, you have to do at least the operas where you are more well-known. So what can you do? [sighs] And almost always you have to accept the cast they impose. Maybe sometimes you are not very happy because you prefer other partners or another conductor, but making records is not to do art; it's just to do business. This is the part of my career I don't like.

BD: You'd rather be on the stage?

AK: No, I'd rather be an artist, a singer and not a businessman in this profession. But you know everything around you, so you have to accept it even if you don't like it.

BD: Do you enjoy doing concerts?

AK: I prefer to do operas. Only for one reason

AK: I prefer to do operas. Only for one reason

— in the opera you have one character to develop in three or four hours. In concert, you have to sing different arias from different operas with different personages. It's terrible to have to create something in three minutes. It's not a question only to produce a sound and make notes. This is easy. But you have to work in every aria to give the audience the right impression of what it means. You have to concentrate the whole opera in one aria, and this is very, very difficult and it is very, very tiring. I feel dead at the end of a concert.

BD: Is this true in songs as well as arias?

AK: I think so because songs also have meaning. They talk about something and you have to feel like what you are saying is true.

BD: Do you sing any of your roles in translation?

AK: I sing the French operas in Italian.

BD: Do you enjoy them in translation -- do they work?

AK: Sometimes it is good. Not all operas, but some are very good translations. For instance, I think Werther's aria (Ah! non mi ridestar) is very nice in translation, very poetic.

BD: Would you ever sing La Favorita in French?

AK: No. They've never offered it to me. I can't tell you if it's better or not because I don't know. I've just sung The Regimenet's Daughter in French and Italian, and both are very nice. Doinizetti wrote it first in French for Paris, then was ordered by La Scala to do it in Italian.

BD: Did he change it?

AK: Yes, it's a little changed, and I did something very unusual. In the French edition, the big aria with the nine high C's is the same as in the Italian edition. But in the French edition, there is a beautiful aria at the very end that is not in the Italian edition. Instead, he put one in the first act with high C's and everything. I sang it in French in America and when I did it in Venice in Italian, I wanted to sing this extra aria and they said OK. I did the translation myself and so this is the only edition in Italian with the three arias.

BD: Do you enjoy singing the high C or is that just a chore?

AK: No, I enjoy it. I like it. It's not difficult for me.

BD: What about the D?

AK: I've sungPuritani for more than twenty years with the high D's and nothing has happened. Everything was perfect. I have to tell you, though, the high D is not normal. I always thought that Puritaniin the actual conditions is an inhuman opera for a tenor.

BD: You don't sing the High F, do you?

AK: No, no. That is impossible. You'd have to do it in falsetto, and falsetto is completely wrong. But when the opera was born, the tenor sang with a sopranist voice and they use it to sing the high notes in falsetto. It was a technique to develop the falsetto.

BD: What's the difference between falsetto and head-voice?

AK: I really don't know. I know when somebody sings in falsetto and when he sings in real voice, but because I don't know how to do a falsetto, I don't know how they do it. It's a different way. I think it's using only the high resonance without the petto voice (chest voice). But I'm not so sure. You have to use the petto voice and put on a very high way to do the high notes. This is what I do and what I always did. But now you have to sing Puritaniwith a big voice, and I really think that I was the only one that for more than twenty years sang this opera always in the original keys. When other tenors sang it in the original keys, it was only for a short period and then they transpose the arias down.

BD: You've paced your career very carefully by singing only the roles that fit your voice.

BD: You've paced your career very carefully by singing only the roles that fit your voice.

AK: Yes. First of all, you have to know your instrument and what you can do with it. Then it's easy to decide what to do.

BD: How difficult is it to say No?

AK: This is very difficult, but you have to because your voice is more important than everything. Often people say you have to sing this and this, but I know what I have to do.

BD: You enjoy singing Bellini and Donizetti?

AK: Bellini and Donizetti, and French opera.

BD: That's the sphere you do. Do you find yourself branching out at all?

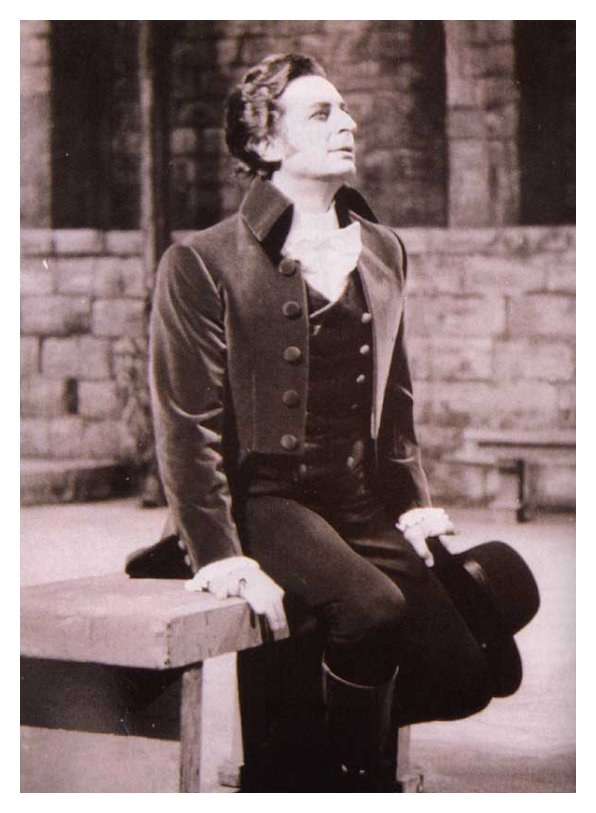

AK: I've always sung Rigoletto and Traviata, and I still do these. I did Fenton in Falstaffat the beginning of my career and also Gianni Schicchi and many things that I don't do now, like the Barber of Seville and Sonnambula.

BD: Why no more Barbers?

AK: It's a lot of nothing happen. When you arrive to a point of your career where you're well-known, the audience wants something very impressive and spectacular. I sing Romeo and that's OK, but if I sing Barber of Seville, nothing happens. It's a difficult opera that I respect very much and I like it.

BD: Is it our fault not to appreciate you in the Barber?

AK: Of course! [Laughter] But the theaters are very practical people. Some idealistic artistic manager can say he would like Alfredo Kraus to do the Barber, but they can't spend money for nothing happen. They want a big impression in the way they employ the money. So for a tenor like me they want Favorita, with the high notes and beautiful arias. Or they want Manon, Werther, Rigoletto, Romeo. This is what they want.

BD: Are there some new roles that you are learning?

AK: I just did Romeo for the first time this year and for the moment I'm not interested in any more. Maybe something could arrive later, but not now.

BD: If a composer came to you and said he was writing an opera for Alfredo Kraus, what would you tell him?

AK: I'm not interested. I have enough beautiful operas in the normal repertoire for a lyric tenor.

BD: Tell me about the two Fausts. You sing both the Gounod and the Boito.

AK: I've sung the Boito a few times, but the Gounod many times. Both are different for the music, for the style, for everything even though the character is almost the same. You can't change the Goethe work. It's impossible. It's almost the same in the feeling of the role.

I would like to talk only about the music results because Faustis so well-known and he has to be the same. You don't have to give your own interpretation because there's only one way to do it.

BD: What if a producer comes along and wants to do it differently?

BD: What if a producer comes along and wants to do it differently?

AK: No, I think I prefer the classic way because it is a classic opera. You have to see the castle and Faust's laboratory in the beginning when he is very old.

BD: Here in Chicago you were kind of on a Valkyrie's rock.

AK: It could be very dramatic to the audience, but not to me, really, because, as I said, I like Faust in the very ingenious way. Like a child, you see the Devil. He created smoke in the sky and Faust is working with the liquids and colors. You can't accept a modern story today like this. If you put modern sets, the story is not balanced with the set.

BD: Do you sing any roles that you like the music but not the character?

AK: I did before, but I don't do it now. I just like to sing roles that mean something to me. For instance, probably you know that tenors, in general, don't like to sing Traviata, but I like it very much because I think the Alfredo role is very nice and very important.

BD: Do you always sing the cabaletta?

AK: Yes, but not only for the cabaletta. Everybody thinks that Violetta is so important that everyone else has to disappear because of her personality. I don't agree.

BD: Is Alfredo a strong character?

AK: Yes. Also he has big reactions to her, like in the scene where he throws her the money. Also in the scene with the cabaletta, it is important because the change of his feelings in that moment. You have to show to the audience that you've changed from one position to another.

BD: He becomes more resolute.

AK: Yes. This situation has to finish, I have to go to find a solution. It's important for that reason, not only because I put a high C at the end. It gives something more to the role of Alfredo.

BD: Tell me a little about the Donizetti roles. You've sung Don Pasquale a lot. Do you like Ernesto?

AK: I like it but I don't love it. I like the whole opera, but the master in this opera is Don Pasquale, and the other people go around and around. It has nice singing. It's a very difficult opera for the tenor but nothing important happens. It is only for the people who know how difficult that part is to sing.

BD: He seems like a cardboard character.

AK: Yes, really.

BD: Do you play any evil characters?

AK: It can be a little in Rigoletto. He is a very bad man. He is against everybody. He has only one tender moment, when Gilda disappears. He has a tender moment there, but that's all. Then he changes back again.

BD: He feels something for Gilda?

AK: No, he was disappointed because she disappeared.

BD: Oh, because he wanted her again!

AK: Yes. He's a little like Dr. Jeckyl. He was married, and for the society he had to be one way. But by night he went out for the women of the street.

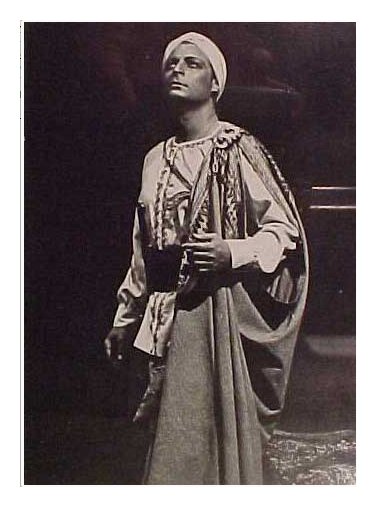

BD: Tell me about the Pearl Fishers. [Photo at right]

BD: Tell me about the Pearl Fishers. [Photo at right]

AK: [With a big smile] Ah, Pearl Fishersis a very beautiful opera despite what the critics say! It is also very ingenious, like a tale for a child. But this is very nice. Nothing to worry about, nothing to think up psychologically. He's just a man who found this beautiful girl, and he's trying to find her again because he lost her and can't find her. At the same time, it is remarkable the way the friendship between him and the baritone is treated in the opera.

BD: Is it not real?

AK: It is... or it could be. I think that friendship is one of the most beautiful and real things that can happen in life. Sometimes it's more than love. On this occasion, for instance, the baritone accepted death in order to save the lovers just because he was a good friend. That's a very positive point of the opera psychologically.

BD: Is it wrong for operas today to try to present psychological problems to the audience?

AK: If it really exists you have to put in evidence, but what I don't like is when you have some stage directors who feel they have to even if it's not in the opera. They invent things, too, and I think this is the wrong way. In my opinion, the stage director and the artist have to explain to the audience what is happening in a particular libretto, in this particular opera. For instance, the Werther I sing is not the Werther that Goethe composed. It is different, it is a libretto with music. I have to be clear to the audience about what I am representing at this moment. For that reason, I have to explain to audience what happened in this libretto with the music, not what Goethe did. Sometimes stage directors like to go back to the origins and start to do many things on the stage, and the audience doesn't know what it all means. They ask why? If they know the opera or if they read it in the program, they expect this particular opera with this libretto. We, therefore, must make it very clear and simple, and not what we would like to happen.

BD: Are stage directors going too far, then, in many instances?

AK: Sometimes. Sometimes they go too far and I don't think it is correct.

BD: Is the music more important than the drama?

AK: It's different in different kinds of operas. I don't say it's more important. To the eyes of the audience, sometimes the drama is more important and sometimes music is more important. You have different kinds of opera. In Donizetti and Bellini, the librettos are so simple it's just a pretext to let you sing. But in the more modern operas like Verdi and Puccini, sometimes the drama is more important.

BD: Do you sing any contemporary operas?

AK: No. I've just sung, many years ago, Dialogues of the Carmelites and Vida Breve of Falla. That's all. In concerts I've sung modern things such as Schoenberg, Berg, Hindemith.

BD: Would you ever sing a role like Alwa in Lulu?

AK: No, never.

BD: Since you are a Spaniard, who are the Spanish opera composers?

AK: We don't have opera, we have zarzuealas.

BD: Is the zarzuela the Spanish musical comedy or the Spanish operetta?

AK: Yes, it is. It's kind of between opera and operetta. Many are very beautiful.

BD: Why don't we know them here, or are they peculiarly Spanish?

AK: You'd have to find an impresario who wanted to take the risk in order to produce one. I think in New York sometimes they have zarzuelas in concert. Of course, in New York you have a very big group of Hispanic people.

BD: How do the different theaters affect your performance — big theaters, small ones, etc.?

AK: I prefer particularly the small theaters because the voice is the voice. It is not a big instrument and needs some kind of help that can come from the acoustic qualities of the theater. The theater has to be built in one way, with materials good enough to help and protect the voice

— wood especially — and it has to be the right size. The very big, modern theaters don't have acoustics that help very much. They use modern materials and don't know about helping the voice. The stage has to be wood, both the theater and the settings on the stage. Everything should be wood, not concrete. Concrete doesn't give any resonance to the frequencies of the voice. In modern theaters, they don't do that.

BD: Do you enjoy singing in Chicago?

AK: I do enjoy Chicago, but I don't think it's particularly good for the acoustic. This is a very big theater, too. The only very big theater that I know that has fantastic acoustics is the Colón in Buenos Aires. It is a classic in construction. It's about 4500 people, so it's enormous but beautiful

AK: I do enjoy Chicago, but I don't think it's particularly good for the acoustic. This is a very big theater, too. The only very big theater that I know that has fantastic acoustics is the Colón in Buenos Aires. It is a classic in construction. It's about 4500 people, so it's enormous but beautiful

— perhaps the most beautiful theater in the world — and it is unbelievable for the sound.

BD: So if you have the choice of singing there or someplace else, do you lean toward Buenos Aires?

AK: No, not really. I've sung there only two times in two different years, that's all. You don't choose the theaters only because the acoustic is good or not good. There are many other things to consider... if they give you the operas you want, if you agree with the cast and the conductor, if you like the people who work at the theater, if the fee is good enough, and many other things. The acoustic is probably the last thing we think about. It's very important, but does not make the decision.

BD: I would think it would be very difficult to sing on a stage with no setting at all, with just empty space all around.

AK: Yes, it happens sometimes there is no cover behind the voice. It actually happens many times, but it is much better when you are protected. Then the voice goes to the audience, whereas with no protection the sound stays on the stage instead of being projected to the audience.

BD: Do you ever work behind a scrim?

AK: No. Sometimes there are phrases to be sung backstage

— like the serenade in Don Pasquale. But there the author wanted the impression of distance.

BD: Do you find a special place on stage where the voice is helped the most?

AK: We think so, but the acoustic on the stage has nothing to do with the acoustic in the audience. Sometimes the stage is very acoustic for us on stage, and when that is the case, the audience is not. And the opposite is also often true

— when you don't hear your voice on the stage, the voice is usually being projected quite far. But when someone comes to me and says a certain place is the best and I should try to always sing from there, I say that it's impossible because I have to move. Sometimes I'm on the right, other times on the left. It also depends on where you are sitting in the audience. It is very difficult to know, really. The only thing we know is that we have to sing, that's all.

BD: Let me ask you about one last role, the one you will be returning with

— Hoffman.

AK: Oh, I like it very much. I think it is a very beautiful role.

BD: Is Hoffman stupid to fall in love with the doll?

AK: No. It's not a real story. It's about a man who must do what he is born to do. He was born to be a poet. If he wanted to love women, it's OK, but the author put the Devil there so every affair has a bad ending. In the end he realizes that everything was a dream with no posterity to be immortal.

BD: So then the villains are personifications of the Devil?

AK: Oh yes, sure.

BD: Are the four women personifications of temptation?

AK: Yes, because he wanted to dedicate his life to things of the world

— one was a love with a doll, another was love with a courtesan, and then the pure love was Antonia.

BD: Does it make a difference to you which order the acts are played? Sometimes the second and third parts are reversed.

AK: I prefer Antonia at the end because it's going from different grades, different graduations

— from stupid love for the doll, the passionate love with the courtesan, and the pure love with the pure girl. This is the way I prefer. Normally they do Giulietta at the end, I don't know why. He was in love with Stella. She was the actress and thus acted the parts of the doll, the courtesan and the singer.

BD: Are these three dreams of Hoffman?

AK: Yes, dreams or, if you accepted the old way like I accepted with Faust with the devil, it was real. But he wanted a modern conception psychological, they were dreams. At the end, Stella comes to find him, to meet him and to be lovers, but he was sleeping.

BD: Was he drunk then?

AK: No, not drunk, but asleep. Maybe a little drunk, but not much. Just a little because immediately when Stella disappears he realizes that he also lost Stella. Then he says he has to be a poet because he hears the muse tell him that everything was a dream and the only real love is the muse that loves him to the end. So Hoffman is not stupid. He is not clever; he is a poet who thought in a wrong way that he could be different. He thought that he could be a normal man like many others while not realizing that his life is to be different.

BD: Was he then kidding himself until the end?

AK: I don't know. He understood that he was wrong, that the three women were only Stella, and he lost Stella. So the only romance for him was his work for the future of being a poet. His inspiration was the muse, not Stella, not everybody. Only the muse would inspire him to be a poet, to make verses.

BD: You enjoy singing.

BD: You enjoy singing.

AK: I enjoy singing, yes. It's the only thing. My career is everything to me.

BD: Thank you for all that you have given us, and for the conversation today.

AK: Thank you. There are many singers and very few are so appreciated.

BD: Are there too many singers today?

AK: Not too many, but it's not bad. I don't think it to be a problem for the future. Many singers are coming out, many people study. The problem is to find a good teacher.

BD: Are there some young Alfredo Krauses coming along?

AK: I don't know.

BD: Do you consider yourself a young Tito Schipa?

AK: No. First of all, because I am not so young! [Laughs] Second, because we are very different voices. Tito Schipa, for me, is the greatest singer of the world. I'm not talking about voice, I'm talking about singing. His voice was small, but it was lovely because his singing was lovely. If you like something, it is beautiful because you like it, but it doesn't have to be beautiful for everyone else. Maybe a voice is not beautiful, but you like it so it is beautiful for you. For me, Tito Schipa had a beautiful voice, but others who like big voices, said his voice was nothing. It wasn't a beautiful voice, but the way he said things was beautiful and for that reason his voice was beautiful. Pertile was the same. His voice was not really pretty, but for me it was fantastic because I like the way he sings.

BD: Pertile was more heroic.

AK: Yes, but even being more heroic, he was a great singer. He managed his voice in the beautiful bel cantoway even with the heroic or dramatic voice, and that has disappeared today. Dramatic voices today don't sing in a bel canto way.

BD: Have we lost this now?

AK: We've lost the style because we don't have the technique to do things like Pertile such as mezza-voceand the beautiful line in the pure bel canto style.

BD: Will it ever come back?

AK: I don't think it's lost forever. I'm not modest, but I think I sing in the bel canto way, and if I can do it everybody can do it. You need a good technique to sing in a bel canto way.

BD: A solid foundation?

AK: Yes. You have to be able to manage your voice to do the various things required. Schipa did it, Pertile did it, and we have to do it also.

BD: Will you ever teach?

AK: I am not really dedicated to it, but on a few occasions I did advise. I did some master classes.

BD: Thank you for giving Chicago so much of your time and so many roles.

AK: Thank you. I like Chicago. I like the audience, I like the people, I like the city, and I'm happy here.

Alfredo Kraus, Lyric Tenor Revered for Phrasing, Was 71

By Allan Kozinn, The New York Times, September 11, 1999

Alfredo Kraus, a lyric tenor who was revered for the refinement of his phrasing and the artistry he brought to bel canto roles, died yesterday at his home in Madrid. He was 71.

The cause was pancreatic cancer, his family said.

Although he never received the kind of popular acclaim accorded Luciano Pavarotti and Placido Domingo, Mr. Kraus had a tremendous following among opera connoisseurs. In particular he was admired for his bright, trim timbre, his distinctive phrasing and an assured, self-possessed acting style. In his performances in signature roles like the Duke in ''Rigoletto,'' Alfredo in ''La Traviata,'' Nemorino in ''L'Elisir d'Amore'' or the title role in ''Werther,'' Mr. Kraus avoided empty display, preferring to use a composers' demand for virtuosity as an emotional element, intrinsic to the character he was creating.

Mr. Kraus's career was also an object lesson in how a singer might preserve his voice, despite the temptations to sing too often and too loud or to take on unsuitable roles. It was not for a lack of offers that he did not sing such bread-and-butter roles as Cavaradossi in ''Tosca'' or Pinkerton in ''Madama Butterfly.'' He learned those roles, and he said that he gave single performances of them early in his career. But he decided that his voice would last longer and remain fresher if he confined himself to the lyric roles of the bel canto repertory. Indeed, he was able to produce his high D, at full power and with a lovely ring, well into his 60's.

''It's a matter of knowing what kind of voice you have from the very beginning and learning to use that voice onstage, with the right technique'' he told The New York Times in 1988. ''It is not so easy, because we are using an instrument that is immaterial. We can't touch it, it's only air. We don't even hear it properly, because we hear a combination of inside and outside sound. You cannot go by what you hear, you must learn to be very sensitive to how it feels, and you can only speak of it in a very figurative language.''

Mr. Kraus also enjoyed running the business side of his career. He did not employ a personal manager during his most active years, preferring to make his own decisions, which were often based on instinct. He would not, for example, work with conductors who he felt tried to sublimate performers' personalities, no matter how auspicious the engagement. He limited his schedule to about 60 appearances a year, and although these usually included performances at the Metropolitan Opera, Covent Garden, the Vienna State Opera, La Scala and the Teatro Colon, in Buenos Aires, he also made a point of appearing in small Spanish and Italian opera houses normally outside the limelight.

He owned and personally supervised a small Spanish record label, Carillon Records. Carillon was the first Spanish company to release a complete opera set, a recording of ''Pearl Fishers,'' with Mr. Kraus in the cast.

Mr. Kraus was born in Las Palmas, in the Canary Islands, on Sept. 24, 1927. He enjoyed singing in church and at local celebrations, but his father -- an Austrian who had taken Spanish citizenship -- insisted that he prepare for a career in the sciences. Mr. Kraus earned a degree in electrical engineering, but when he was in his mid-20's, he decided to study singing more seriously as well, first in Valencia and Barcelona, later with Mercedes Llopart, in Milan.

In 1955 Mr. Kraus won the silver medal in a vocal competition in Geneva. He had appeared onstage in zarzuela performances in Madrid, in 1954, but he always gave the date of his formal operatic debut as 1956, when he sang the Duke in a Cairo performance of ''Rigoletto.'' The Cairo engagement also included Mr. Kraus's only performance as Cavaradossi.

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in apartment in Chicago on December 7, 1981. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1987, 1992, 1997 and 1999. The transcription was made in 1982 and part was published in the Massenet Newsletter in July, 1982, and in Opera Scene Magazine in August, 1982. The transcript was re-edited and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.