Lenus Carlson Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

[This interview was held in 1982, and originally appeared in The Opera Journal.

It has been slightly re-edited, and the photos and links have been added for this website presentation.]

Baritone Lenus Carlson

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

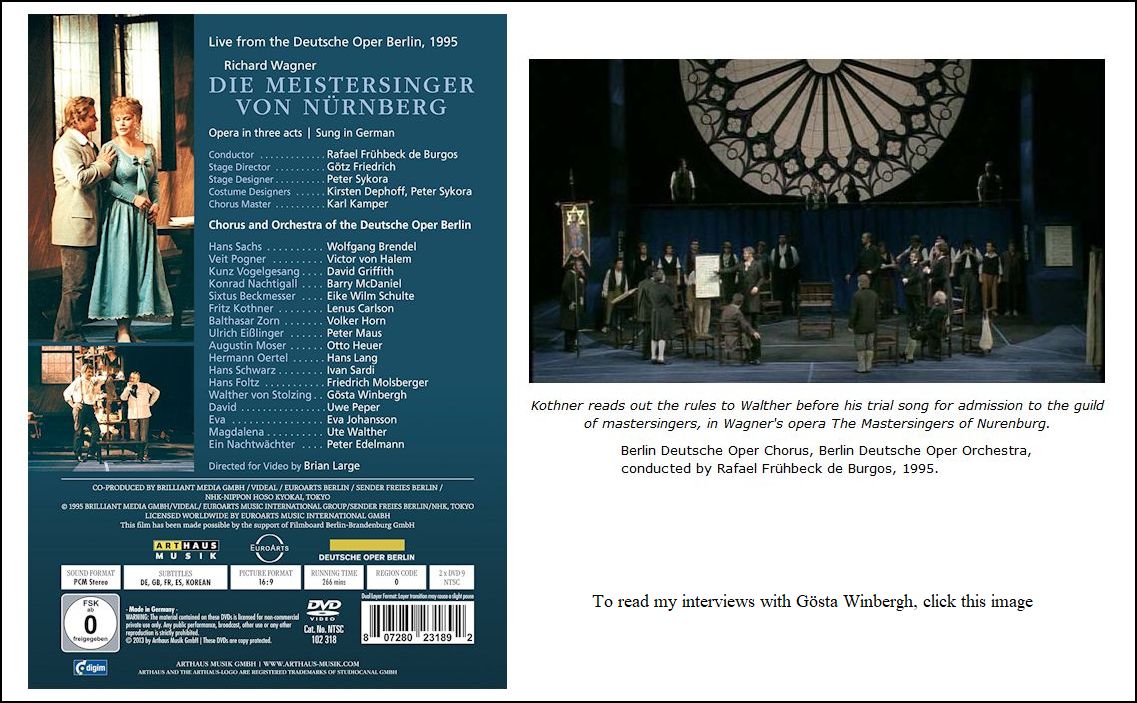

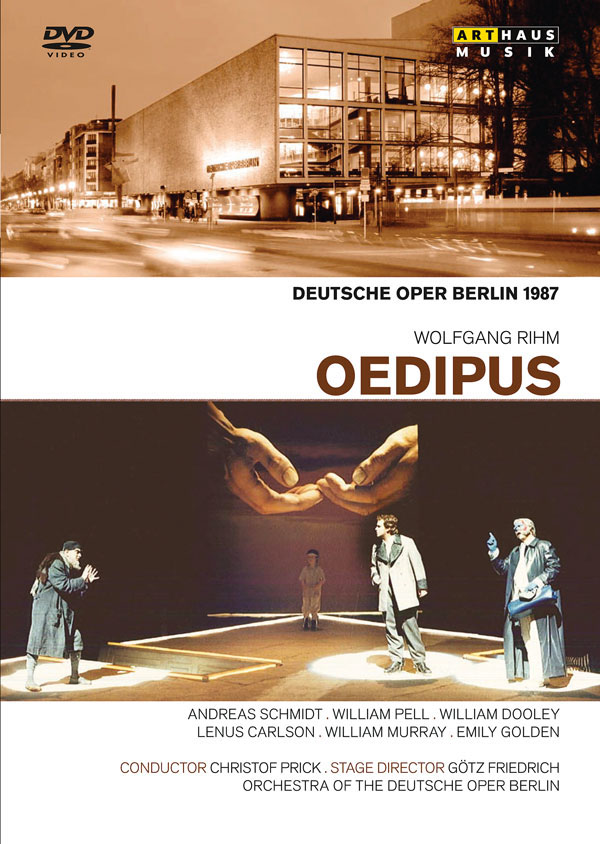

In many ways, baritone Lenus Carlson has led a charmed life

— or at least had a career which, so far, has provided him with plenty of work interesting roles, and a variety of opportunities to perform with the great stars and in leading companies around the world. He was born in North Dakota and grew up on a farm, coming to Milwaukee on occasion to visit family, and touring Chicago with all its cultural interests. He studied at Juilliard, and made his debut at the Met when he was 27. That debut was as Silvio in Pagliacci with Richard Tucker and Cornell MacNeil in the cast. [_Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.] He remained to sing several other roles with the company including Eugene Onegin. This led to appearances in Europe and with other leading American companies. For the last several years he has been ‘_Fest_’ in Berlin, which means he is a member of the resident ensemble. With them he has performed many roles and toured to Tokyo. The company was in Washington DC in June (1982) for Wagner’s_Ring, with Carlson as Gunther.

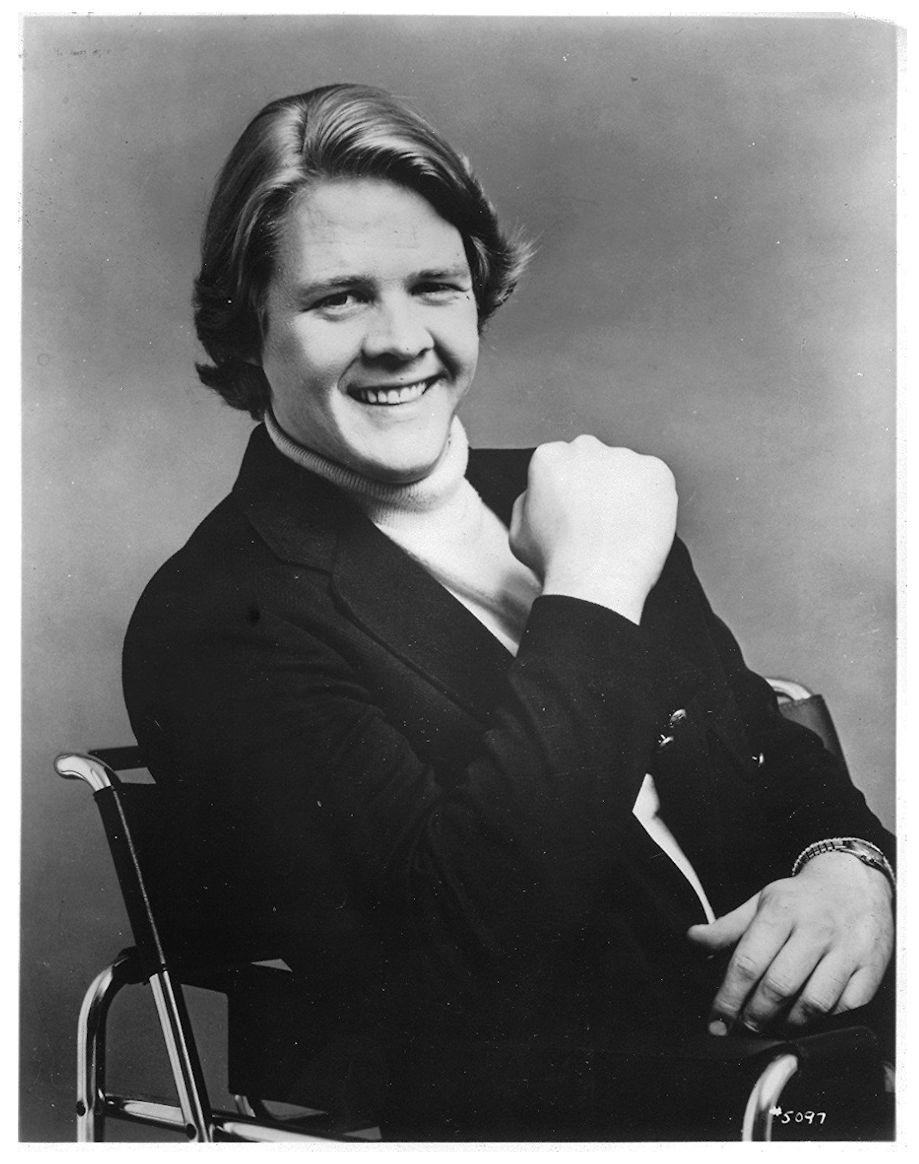

It was just before leaving the States for that Berlin engagement that Carlson appeared in Chicago, again as Silvio, and again with Cornell MacNeil. Also in Chicago were Jon Vickers, Josephine Barstow, and David Gordon, with Carlo Felice Cillario conducting the Zeffirelli production. It was between performances that we met backstage for a chat. Tall, young, and virile, the essence of a lyric hero, he was suffering from a bit of a cold that afternoon, so it was there that we pick up the conversation . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Do you sing with a cold?

Bruce Duffie: Do you sing with a cold?

Lenus Carlson: Sometimes.

BD: How far do you let the cold go before you decide to say no?

LC: As long as the vocal cords aren’t thick, you can sing and it sounds normal. It doesn’t feel so good, but it sounds okay. The problem with a little post-nasal drip is that you may push your voice a bit, and that’s an iffy situation.

BD: Do you take anything for the cold?

LC: No, nothing special. One of the things I’ve learned is to never take any of the things doctors prescribe. I take vitamins regularly anyway, but decongestants tend to prolong the cold, I think. Just let nature take its course.

BD: Is being a singer like being an athlete?

LC: It sure is, and you’re constantly training. I was fortunate and did sports when I was growing up, so I had a well-balanced life. One of the hard things when you come to a new city

— and you’re always in a new city — is to find that comfortable place to work out so you get enough physical exercise. I wind up walking a lot. And I look for places to stay that are comfortable. Here in Chicago, I’m right by the lake, so I walk there a lot and get a lot of good air. I like to play golf, so I search out a good public golf course. That is really what keeps singers healthy — lots of air and exercise.

BD: Even on the day of performance?

LC: Yes, unless you’ve got a cold or are tired. Generally, I sleep well, then get up and hike, come back and take a nap, and feel great. But it is like being an athlete. You want to have your whole body in line. My fifth vertebra down will go out, and that will give me tension and tight shoulders.

BD: Opera houses have vocal coaches on staff. Perhaps they should also have chiropractors and physical therapists?

LC: They should have! I’m a believer in chiropractic because when your circulation comes right and all your glands work right, your muscles relax and that’s the key to singing well. Almost everyone takes his tension somewhere

— either in his neck or lower back — and it exhausts him. He gets tired. Remember, we stand a lot, and if you don’t stand correctly, your lower back takes the tension and you get really tired. Then you go home, and if your bed isn’t exactly right, you come back the next day tired, and then you’d rather ‘mark’ with your voice instead of singing out full, and your voice gets tired. So down through the weeks of a rehearsal period, you start to wonder what’s the matter. Then at the final dress rehearsal, you don’t do your best because you’re exhausted. You have a day or two to recoup before the first performance, but you’ve lost a lot of time when you could have been feeling good, and what’s your life other than feeling good?

BD: How do the different-sized houses affect your performance — big ones, small ones, etc.?

LC: I’m rather used to big houses, like the one here in Chicago. Europeans who start their careers in smaller houses have to adjust to the larger size. I’m happy to be able to sing in the large ones and adjust to the smaller ones. That’s certainly easier. Every house sounds different, and you get used to it as you rehearse. This one feels good. I get a feeling of substance out there. It’s not like singing into a cotton wall. San Francisco took me a while to get used to. I wasn’t getting back quite what I do here, or at the Met. They’re all a little different, but you get used to it. I don’t like a ‘live ‘house as much. When the note reverberates and sounds great, then I start to give more, trying to match it and make it ring more and more. Then I get all blown out of whack. I’ve done a lot of solo recitals in concert halls and churches, and the resonance just feeds me, and I’m trying to break the windows, and that’s not good for the voice at all.

BD: How do you balance your career

BD: How do you balance your career

— concerts and opera performances?

LC: I started in 1972 with Columbia and its Community Concerts series, so right from the beginning I jumped out with popularity on the concert tour. I did about 135 recitals in three or four years, plus the Met debut and Convent Garden debut, and all the operatic roles after that. I like concerts even more and more as I learn how to do it better. The ideal thing, as I’m sure everybody would say, is to have one-third concerts and recitals, and two-thirds opera. Others might bend a bit more to concerts, but this is the balance I like. However, I’ve sort of been priced out of the concerts. When I started out, I was at the Met and everyone wanted a lower-priced singer on the way up. Now I only do maybe five concerts a year. Later on, I might get more famous, and it will pick up again, but who knows how that goes? You move along, and take the steps you feel you have to take. I’m certainly not in a position to call my shots.

BD: How do you decide which roles you will agree to sing, and which you’ll turn down?

LC: I’m constantly turning down roles, some for vocal reasons, others for psychological reasons, for instance Rigoletto. That represents the epitome of great baritone repertoire, and in the late ‘70s I was asked to do it. I turned it down because I didn’t feel I could handle it. The demands of it, vocally and dramatically, were too much. Maybe someday, but I didn’t feel that someday was here then. Perhaps, because of my physique, I won’t be a good Rigoletto. There are singers I admire vocally who don’t cut the figure on stage of what you imagine Rigoletto to be. Some do well and are marvelous actors, but they’re working real hard to look like a hunchback. My ‘forte’ has always been young parts, the young, lyric, romantic roles. Silvio in Pagliacci is like a tenor part in a way.

BD: Do you ever wish you were a tenor, and got the girl more often?

LC: [Laughs] Well, there’s a lot more to being a tenor than just getting the girl. I’m glad I’m a baritone, but a tall, good looking tenor has it made. There are a million lyric baritones, so there’s more competition. But you are what you are, and I live that way. I like what I am, and I can’t imagine not being me. It’s a stretch for me as I head into the more evil roles.

BD: Do you like being evil on stage?

LC: [Hesitating] I guess so. I get a certain energy from the evil characters. I’m really too nice a guy off stage, so it’s interesting to be mean and ugly and awful. In Lulu I did the Circus Juggler who’s a jerk

— all muscle and no brain, and thinks of himself as a one-man stud-farm, which is basically the relationship he has with Lulu. So I had a ball doing this guy. I’d like to sing Scarpia because he’s evil.

BD: Do you ever sing characters that you don’t like

— ones that fit your voice, but you’ve no sympathy for?

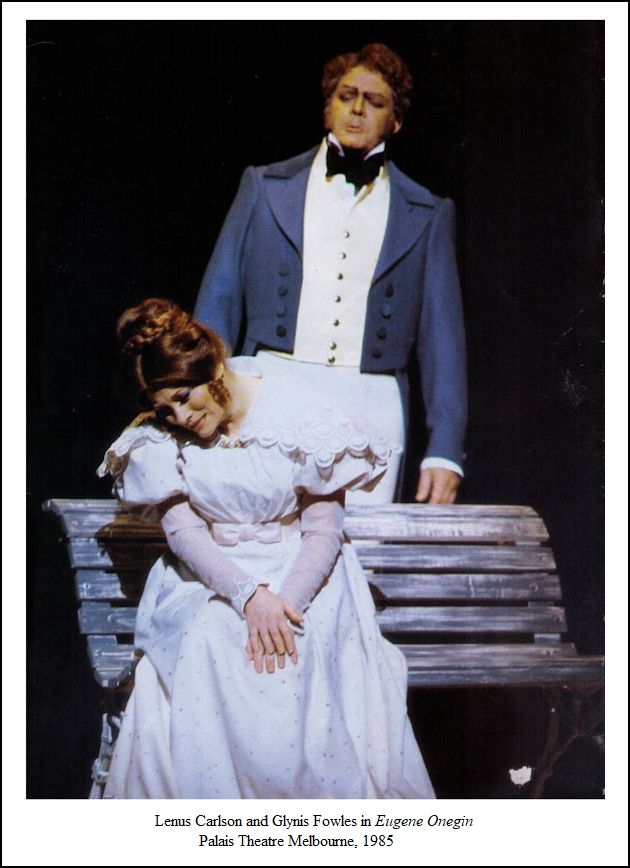

LC: Escamillo. He’s shallow and one-dimensional, and there’s no chance to develop the character. He comes in and sings this one pompous, egotistical aria, and then comes back a bit later. He’s nothing, but it suits me vocally. Even Silvio really doesn’t have enough to do. It suits me fine, but I don’t get a chance to really draw the pictures I’d like to. To a certain extent Eugene Onegin is that way. He works like a dog all through the opera, and he’s not a likable person. The tenor just creams the audience with his aria, and the soprano has this one fabulous scene. The bass walks on, sings an aria and stops the show. Onegin has none of those kinds of things, but he has to work hard all evening.

BD: Would rather kill or be killed on stage?

LC: I don’t know. It’s fun both ways! I like getting stabbed by Jon Vickers here.

BD: Ever had any accidents

— scenery falling, or trap doors that didn’t work correctly?

LC: I was doing Don Giovanni once, and there was a kind of bannister or balustrade which I was to climb up on at the very end, and fall into hell at the blackout. Behind that they had flash pots. So, I fall down out of sight, but right by a flash pot, and I got it right in my face. That wasn’t much fun. It burned all the hair off my face, but didn’t burn the skin too badly.

BD: Did you take the curtain call?

LC: [Laughs] Yes. I don’t mean to make it out worse than it was, but it was an incident. I’ve had other things happen. In Scotland, I was doing a world premiere where I was a lord in love with a milkmaid, but I have to call it off because of the social implications. She was wearing some tear away petticoats for a later scene where she was to be raped, but just as I entered, those petticoats fell away, and my line was,

“No, Christina, not today.” Now I’m a professional, and I don’t break up on stage, but at that moment, I could not sing my next lines. It was too much, and everyone was laughing about it. I just lost it completely, along with everyone else.

BD: Do you like singing world premieres?

LC: I’ve done a few. We did two or three a year at Juilliard. I did The Losers (1971) by Harold Farberman (1929 - ). It’s a motorcycle opera, based on a

’50s gang. It got good notices. [Review from The New York Times appears below.] I was in leather and chains, and had long hair and rode a real motorcycle on stage. There was a rape scene, and an initiation scene where we had to crap all over another character and burn him with cigarettes. It was really a mess, but it got a lot of attention. Time magazine played it up. The local chapter of Hell’s Angels thought it was denigrating to their society, and there were lots of police around. The composer conducted the work.

The Opera: Fellowship of the Road in The Losers

By Harold C. Schonberg

The New York Times, March 28, 1971

It's relevant, “The Losers” is, if motorcycle gangs, violence, a gang rape and other assorted gore can be considered relevant. Harold Farberman has put all this into his new opera, which had its premiere Friday evening at the Juilliard Theater. Yes, it's relevant, but it's also an opera, and there is a motor cyclists ballet, just like the Bacchanale in “Faust.” Or maybe “West Side Story.”

These leather‐draped kids, these Blights of the Grail, are headed by a big, blond Maximim Leader. Of him it can be said, as Tosca almost said of Scarpia, “Avanti a lui tre mava tutta California.” The gang acts up, the members have a symbolic initiation ceremony in which a latter day Gurnemanz celebrates sort of Black Mass, and they are indeed the new fellow ship of the road in an animal subculture where fist and sex share the throne.

Barbara Fried's libretto is simple enough. Most of the action takes place in the hangout of a gang called The Losers. This gang recognizes no morality, and terrorizes the neighborhood. A girl gets mixed up with the leader. She is an innocent who ends up getting raped by the gang. The leader is killed in a fist fight. The only man with decent tendencies is killed by the gang. Through all this promenade a pair of girls, acting like a Greek chorus. They sing, utter gnomic utterances and say wise things perhaps. [_Photo of Farberman at left is from another source._]

Barbara Fried's libretto is simple enough. Most of the action takes place in the hangout of a gang called The Losers. This gang recognizes no morality, and terrorizes the neighborhood. A girl gets mixed up with the leader. She is an innocent who ends up getting raped by the gang. The leader is killed in a fist fight. The only man with decent tendencies is killed by the gang. Through all this promenade a pair of girls, acting like a Greek chorus. They sing, utter gnomic utterances and say wise things perhaps. [_Photo of Farberman at left is from another source._]

Mr. Farberman's score is avant‐garde. His vocal lines, mostly declamation, use the favored wide skips so beloved of the post‐serialists. The orchestration is noisy and violent. There is some very stylized post‐serial jazz from a quartet on the side of the stage. Mr. Farberman is nothing if not doctrinaire, and he has used every stylistic cliché of the idiom.

In this kind of idiom, striking effects can be achieved. The massed dissonances are fine for making angry noises and squealing commentaries on life. But lyricism? Forget about it. Here and there the composer has tried for stylized kinds of tunes, but has ended up with constipated lines that go nowhere. Something in Mr. Farberman hates a tune.

Thus there is no relief from the prevailing post‐Pierrot speech‐song. Mr. Farberman is a captive of doctrine. Other composers these days are more relaxed. Several who work in an idiom very close to Mr. Farberman's do not hesitate to use elements of real jazz, or rock, or whatever, to vary the texture. But Mr. Farberman has neither the inclination nor, perhaps, the imagination to depart from his set scheme, and the result was a dreadful musical monotony relieved only by the violence of the action on stage.

Yet, with all that action, the libretto was curiously conventional — Hell's Angels types and all. For this was not modern music drama. This was in some respects an old-fashioned opera, where the action stops in one spot for a ballet, and in another for an initiation ceremony that is supposed to give the psychic key to the story.

Anyway, the motorcycles were handsome.

And so was the production. It was brilliant, and by far the best thing I have seen from the Juilliard American Opera Center. Douglas Schmidt's settings are imaginative and effective, full of sleazy atmosphere, coming apart in the Best Broadway manner to give the dancers leg room. John Houseman directed, and there are not many more professional figures on the American stage. The costumes by Jeanne Rutton must have sent a thrill of desire into anybody who ever wanted to go vroom.

And, as might have been expected, the young cast was able to identify with the action. The kids leered and strutted, and looked tough, and swung a mean right hand, and kicked an even meaner right foot. Prominent in the proceedings were Lenus Carlson, John Seabury and James McCray, all fine, all convincing in their roles. Barbara Shuttleworth, in a rather negative role, did all that could be asked.

The two motorcycle muses (or furies, or Greek chorus) were, for some reason, amplified. Presumably they were intended to be outside of the action. Anyway, their voices came from. On High. The composer conducted, presumably authoritatively. At the end, there were great yells of approval, But I still think “The Losers” is, in a crazy kind of way, American kitsch.

The Cast

THE LOSERS, opera in two acts with music try Harold Farberman and libretto by Barbara Fried. Commissioned by the Juilliard School. Premiere by the Juilliard American Opera Center at the Juilliard Theater. Sets designed by Douglas Schmidt. Costumes designed by Jeanne Button. Lighting by Joseph Pacitti. Stage director, John Houseman, Choreographer, Patricia Birch. Conductor, Harold Farberman.

| Buzz | Lenus Carlson |

|---|---|

| Donna | Barbara Shuttlesworth |

| Joker | John Seabury |

| Marie | Julia Lansford |

| Gino | John Mack Ousley |

| Duo | S Barbara Hendricks |

| S Barbara Martin | |

| Ken | James McCray |

| Tiny Alex | Robert Benton |

| Olsen | Frank Spoto |

BD: What’s it like working with the composer?

LC: Fun. We also did Lord Byron by Virgil Thomson, and Huckleberry Finn by Hall Overton (1920-1972). Unfortunately, none of these works has been done again, which is too bad. We worked for two months for just a couple of performances.

Lord Byron is an opera in three acts by Virgil Thomson to an original English libretto by Jack Larson, inspired by the historical character Lord Byron. This was Thomson's third and final opera. He wrote it on commission from the Ford Foundation for the Metropolitan Opera, but the Met never produced the opera. The first performance was at Lincoln Center, New York City on April 20, 1972, by the music department of the Juilliard School with John Houseman as stage director, Gerhard Samuel as the conductor, and Alvin Ailey as the choreographer. A performance of a revised version, by the composer, took place in 1985 with the New York Opera Repertory Theater.

* * * * *

The New York Times, May 16, 1971

This 'Huck Finn' Is Not for Children

By RAYMOND ERICSON

The Juilliard Opera Center's last premiere, given in late March, was Harold Farberman's "The Losers." It was about today's youth, specifically a gang like Hell's Angels. The company's next premiere, due this Thursday and Saturday, is about the youth of another and more innocent era, the characters in Mark Twain's "Huckleberry Finn." The opera is by Hall Overton, a 51-year-old composer on the Juilliard faculty. He collaborated on the libretto with Judah Stampfer. [The opera would be conducted by Dennis Russell Davies.]

Overton was commissioned to write an opera dealing with youth, which would hopefully appeal to young people and relate to the way they feel today. The composer thought the Twain novel would fill the bill. "Huck," he says, "was concerned over issues of conscience, over moral issues. He rejected civilization as he saw it. He ran away from it. His main goal was to run to some place where he could be free. His strongest relationship was with a black man." [_Photo at left of Overton with Aaron Copland is from another source._]

Overton was commissioned to write an opera dealing with youth, which would hopefully appeal to young people and relate to the way they feel today. The composer thought the Twain novel would fill the bill. "Huck," he says, "was concerned over issues of conscience, over moral issues. He rejected civilization as he saw it. He ran away from it. His main goal was to run to some place where he could be free. His strongest relationship was with a black man." [_Photo at left of Overton with Aaron Copland is from another source._]

Overton says that the libretto will not please everybody, because they had to leave so much out. "We have concentrated on three main areas: the characters and relationship of Huck and Jim; crowd scenes -- it was important that they be represented because Twain uses them as a foil for the closed world of Huck and Jim; and the symbolic forces of the river and the raft and the freedom that seems to be there wherever the river takes you.

"We have tried to preserve Huck intact as much as possible. He is what he is in the novel except that we have advanced his age from 13 to 16. Jim's character is altered somewhat. He represents an older, wiser man who instructs in his own way. Towards the end, we have made a real change, Jim is freed, as in the novel, by his former owner, but instead of going back with Huck and Tom Sawyer, he takes off on his own to continue his original mission to free his immediate family."

Overton waited until he had a workable libretto before he developed the opera's musical style. "The thing I felt had to be preserved was the language. Twain is a master of the vernacular, and I had to start with that. I took the rhythms and inflections of the spoken language and wrote a continuous recitative, with arias, in most cases, being implied. The music is sometimes dissonant, sometimes very tonal, but at all times, I hope, consistent with the aim of the piece -- the American language as Twain so truly recorded it. I have utilized by background in jazz for Jim."

People who have heard about "Huck Finn" have frequently asked if it is a children's opera. Definitely not. It is a serious opera by a serious, well-regarded composer.

BD: Should these operas be done again?

LC: Some should. Lord Byron was kind of nice, and I wish someone would do it again.

BD: I understand you’ll be leaving soon for an engagement in West Berlin? [Remember, this conversation was held in the fall of 1982, when Berlin was a divided city.] LC: Yes, I’ll be Fest there [_a resident member of the company_] for six months of the year, and I’ll do guest engagements and concerts the rest of the year. It will be nice to stay put and have an apartment, and lead a fairly normal life. I’ve sung in Europe every year for the last eight years or so, but only a few weeks at a time, so it will be interesting to be a German resident. I had a lot of German studies in school, but I’m sure the language will get even better very quickly.

LC: Yes, I’ll be Fest there [_a resident member of the company_] for six months of the year, and I’ll do guest engagements and concerts the rest of the year. It will be nice to stay put and have an apartment, and lead a fairly normal life. I’ve sung in Europe every year for the last eight years or so, but only a few weeks at a time, so it will be interesting to be a German resident. I had a lot of German studies in school, but I’m sure the language will get even better very quickly.

BD: What are the roles you do often?

LC: Eugene Onegin is one I love to do. Russian is a beautiful language to sing in. I did that in Amsterdam, and later several seasons at the Met. Another favorite is the Count in Figaro. I’ve only done a couple of productions of Don Giovanni, but that’s another I love to do, and will do again soon. That’s one reason to go to Berlin

— to get the opportunity to do more of these roles, and to broaden my international opportunities. Many of the big international stars are Fest some place. It’s a way of life for many singes. You have both a home house and the guest appearances all over. I look forward to getting into a bit of Wagner because I love the music.

BD: Tell me about Don Giovanni. Is he evil or just spoiled?

LC: I don’t think he’s evil. I think that he’s a doer. He’s a manic depressive. Philosophically, he wants to discover what his limits are. He feels like doing something, so he does it. It’s without a lot of moral wondering. He doesn’t think about the ramifications. He doesn’t dwell on too much. He knows what he’s capable of, but he doesn’t think about it a lot. I don’t think he considers if there is a heaven or hell. That’s why he’s quite shocked when the Commendatore comes to dinner. It’s like a race car driver. He goes 180 miles per hour, so he wants to see what 190 is like. Why does he do it? He just does it.

BD: Do you think opera works well in translation?

LC: I think Mozart does well. I like to hear Mozart in English. Everybody laughs more and has more fun. Donizetti also does well in English. Don Pasquale is lots of fun that way. I’ve done Dr. Malatesta, and like it very much. I would think Wagner would also work well, though I’ve not heard it in English. One I would not like to do in translation is La Bohème. Because of the style of the phrases, Puccini operas don’t do well in translation, but that’s my opinion. I’ve studied French and Italian and Russian, and I’ve gotten a feel of the style of these languages and national characteristics, so I’m not your average opera lover. I go to a lot of performances that I’m not singing, but I don’t eat and sleep opera. I don’t listen to it a lot at home. I like popular music, and baroque ensembles, and folk music. I live to sing opera and be in them, but I like other things too.

BD: Does opera work on TV?

LC: Some things, yes. I like the performances more in the theater, but I’ve seen some really good shots on TV, which are beautiful. The ones that are made especially for the screen are great, and having the translation helps a lot, too. However, I’m not sure if I like seeing myself up there when I see the tape later.

BD: Do you like being booked so far in advance?

LC: Well, my repertoire is changing a bit. I’m being more careful so that roles I don’t care for are not coming up so often or so far head. You asked earlier about choosing roles, and in Lulu, the better part is, of course, Dr. Schön. If I do the opera again, I’d rather do Dr Schön. I was offered that part in the Met production, but I feel he should be fifty years old to look the part. I just look too young now, and my voice sounds young. The maturation process will give a different color and shape to the voice.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of opera?

LC: Everything goes in cycles, but opera is a well-established art form. There is no other real vehicle for the human voice. You can’t make the impression in a concert that you can doing an operatic role with all the trappings. The whole picture is absolutely special in the opera house. For the most part, people will become more involved in the arts. There’s more opera now than a few years ago, but there may be a lessening of the quality. It’s become more popular, more like television.

BD: This is why I asked if opera belongs on the same small screen as Barney Miller or The Flintstones.

LC: I think it does. I love to watch television, and I like to see opera there once in a while. But should never become ‘flip’ or ‘popular’ in the crass sense. It’s got to stick to its real values. I’ve had opportunities to do Broadway, but I’m an opera singer, and I like what I’m doing.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

---- ---- ---- ---- ----

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 10, 1982. The transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal in March, 1989. It was slightly re-edited, and photos and links were added in 2018, and it posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.