Lowell Liebermann Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . (original) (raw)

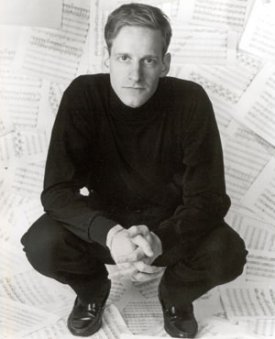

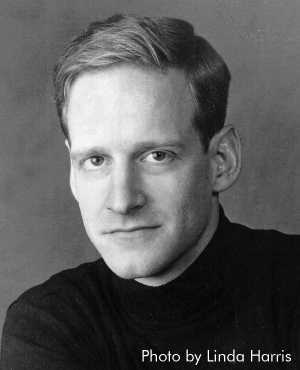

Composer Lowell Liebermann

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

'Tis a rare thing these days for a composer of classical music to be much-performed, but the subject of this conversation has achieved that status. Lowell Liebermann writes music that the public enjoys and musicians understand and support. He by no means panders to anyone, yet his scores are applauded and are willingly re-heard by a diverse audience.

A comprehensive account of his activities and a link to his website are in the box at the end of this presentation. Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.

In August of 1998, Liebermann was coming through Chicago and agreed to stop and speak with me about his ideas. As we were setting up to record the conversation, I mentioned that this chat would be on the other side of a cassette which already held an interview with another composer. So Liebermann would always be linked in my mind with this other creator . . . . .

Lowell Liebermann: I’ve been linked with quite a number of musicians... [Laughs]

Bruce Duffie: Well, let’s just start right there. Do you like being linked with other composers, or do you want to be a completely unique entity unto yourself?

LL: It depends on the composer. A lot of critics, especially those who don’t really have the equipment themselves to listen to a piece of music and really evaluate it on its own terms, start playing the

“influences game.” The criticisms often consist of a list of other composers that the critics are reminded of while they listen to your piece.

BD: You’ve used a little bit of this one and a little bit of that one?

LL: Right. And they almost inevitably mention composers I can’t stand! [Laughs]

BD: In favorable comparisons, though?

LL: It depends. Usually it’s a big cliché of modern music

LL: It depends. Usually it’s a big cliché of modern music

— and modern art in general — that it’s supposed to be a negation of what came before it, and must be absolutely unique and individual. So when they say it sounds like something else, it’s not meant kindly. In fact, I take the exact opposite view; to me, classical music is a continuum and it’s enriched by associations from the past. Not that a piece of music should be slavishly imitating something, but to me those influences are enriching, and it’s what allows you to place yourself as a composer in a cultural context.

BD: So you’ve got to come from someplace?

LL: Yes, and it’s crazy, because Beethoven often sounds like Haydn or Mozart. There are no composers that are totally unique sounding.

BD: Is that a good thing, a bad thing, or just a thing?

LL: I think it’s just a thing, but it can be very funny. For instance, a review of my opera when it was premiered in Europe said that it sounded like a cross between Berlioz and John Adams. I would really be curious to hear what that sounded like! [Both laugh]

BD: Well, do you try to sound like anybody else, or do you try to sound only like you?

LL: I don’t try to do either. The way I approach composing is a very organic process where I like the overall large form of the work to develop out of the smallest idea or seed that you’re working with. To me, the process of composing is, in a way, the search for an inevitability that this is really the only right way that this material could develop. It’s about just looking at the material and finding the right way for that to develop; it’s not about trying to sound like anything.

BD: Are you developing it in a certain way, or are you following its development?

LL: More the latter. Occasionally in a piece, one will be working with material that either reminds one of another composer, or another piece of music. Then sometimes you work in references in your own music that explicitly refer to another composer’s work. But I don’t think any composer can escape being influenced.

BD: Are the references homage, or tweaking?

LL: Usually homage. Sometimes tweaking homages!

BD: Should we know what those references are, or should they just be fleeting ideas that may or may not be grasped by the audience?

LL: It depends. Sometimes it’s very explicit and meant to be picked up. Other times it’s more subtle, sort of an in-joke.

BD: When you’re writing a piece of music, going along and watching its development, how do you know when you’ve reached the end?

LL: When you write the double bar! [Both laugh] No, it’s always pretty clear. It’s a difficult decision and it depends on each piece. It’s sort of like a writer writing the novel. Usually when you start out, you have a pretty good idea of the plot before you begin filling it in.

BD: Do you spend a lot of time thinking before you put anything on the page?

LL: Yes, I do, and then I actually spend quite a bit of time sketching, searching for the material I’m going to use. Once I actually have decided I’ve got my material and I can begin, then I usually compose from A to Z. I usually compose a piece in the order it’s listened to.

BD: But then when you get to the double bar, don’t you go back and tinker with little portions?

LL: Very rarely. I’ll occasionally go back. Often one writes ahead and sketches ahead quickly to get to the double bar. Because you know where you’re going, you know where you want to go, and maybe you’re in a section that you’re not quite sure about some of the details. So you sketch that in quickly and go ahead to the finish. Then you have to come back, but usually I don’t do much revising. I have never really looked back at pieces and said, “Oh, this doesn’t work, or this doesn’t have to be changed.” I tend to compose very carefully and very slowly. I usually don’t put something down on paper unless I’m pretty sure that that’s what I want.

BD: Is it true that each little note gets its moment with you?

LL: Yes. It tends to. One of my aims in composing

— one of my aesthetic ideals — is that there should not be any notes that are not absolutely necessary.

BD: Then once you get it all out and you hear it, are you ever surprised by what you hear?

LL: No, I never have been, I have to say.

BD: That’s good. That means that you’re able to transfer the sound in your ear to the dots on the page, and it comes back at you the way you heard it.

LL: Yes. It usually does.

BD: Once you hear it, do you ever then go back and tighten or change or revise just a little bit?

LL: Very slightly; an occasional dynamic here or there. Occasionally you’ll decide in the strings maybe you want to mute something that wasn’t muted.

BD: You must be a publisher’s dream, then, because some composers go back and after each performance they have a whole set of corrections!

LL: Yes, but nowadays, the way publishing works it’s usually the composer’s responsibility, anyway. The publishers say, “Give us finished materials, and then we’ll publish it.” I suppose the piece that I did the most revision on was my opera, and just because it’s such a big, large amount of music.

BD: This is the Oscar Wilde?

LL: Yes. It’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. I went through it and took out certain things to make the orchestral texture lighter. When you’re dealing with singers onstage in a particular hall, you can never really judge the acoustics exactly. It’s going to be different in each, depending on the weight of the voice. So you always have to account for that. I’ve only done one opera, but composers who have done more than one have told me that no matter when you think you’ve got the finished orchestration down, you get another performance and then there’s always something that has to be adjusted.

BD: Do you like working with the human voice?

LL: I like working with the human voice. I don’t necessarily like working with singers! [Both laugh]

BD: Would you want to take the voices out of the throats and be able to manipulate them?

LL: That would be the ideal situation! Singers are a whole category by themselves, in terms of working with them and the egos you have to deal with.

BD: Do singers like working with you?

LL: I haven’t had too many complaints... or at least they haven’t complained to me!

BD: You haven’t conducted the opera?

LL: No, no.

BD: But you’ve conducted other works of yours.

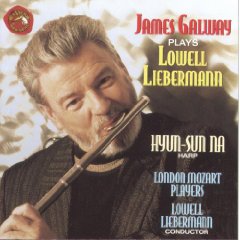

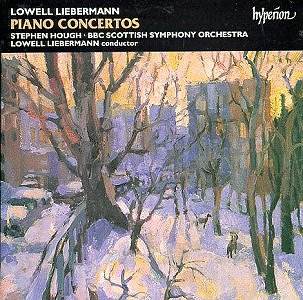

LL: Yes. I’ve conducted the recording of my two piano concertos on Hyperion. And I conducted the recording of my Flute Concerto, Flute and Harp Concerto, and Piccolo Concerto that’s going to be released by BMG with James Galway.

BD: Is it easier or harder working with a huge established artist like Galway? And would you have written differently, or would it sound different, if it was just Joe Competent flute player?

LL: I wouldn’t have written any differently just because whenever I write a piece, I always write for my imagined ideal performer. And even if you’re writing an easy piece, or even children’s pieces, you’re still writing for the ideal pianist of that level. So, which performer it is doesn’t tend to alter the way I write, except in Galway’s case, he has such an incredible sound and such incredible low notes that I did emphasize a lot of that in the flute pieces. He can do anything on the instrument, so I wasn’t afraid to write anything. As far as working with him, he’s probably one of the easiest musicians I’ve ever had to work with.

BD: He seems genuinely interested in putting the music across.

LL: Oh, yes. But he was willing to try anything; he is a composer’s dream, as is someone like Stephen Hough, who’s played a lot of my music.

BD: Now you, of course, are a pianist.

LL: Yes, I am.

BD: Does that give you any more sympathy for writing for that instrument, either solo or concerto?

LL: Sympathy, yes. My piano music tends to be quite difficult, so I know the performers sometimes do curse me. [Both laugh] Sometimes I’ve written things that I knew were quite wicked to do, with full knowledge and sort of a gleeful little smirk as I wrote the notes down. [Demonstrates the smirk] I’m joking a little, but I firmly do believe in the concept of the play-ability of music, that it should be a pleasure for the performer to learn and to play. If you’re writing something that’s so technically difficult and so difficult to memorize and just so gnarly, the pleasure level for the performer really decreases. And being a performer myself, I’ve never lost touch with what that feels like. I think that partly because of the specialization that one finds in universities, where you have to be a major in one thing, for the first time you have students who were brought up as composing majors who didn’t play instruments, or didn’t keep up the performing.

LL: Sympathy, yes. My piano music tends to be quite difficult, so I know the performers sometimes do curse me. [Both laugh] Sometimes I’ve written things that I knew were quite wicked to do, with full knowledge and sort of a gleeful little smirk as I wrote the notes down. [Demonstrates the smirk] I’m joking a little, but I firmly do believe in the concept of the play-ability of music, that it should be a pleasure for the performer to learn and to play. If you’re writing something that’s so technically difficult and so difficult to memorize and just so gnarly, the pleasure level for the performer really decreases. And being a performer myself, I’ve never lost touch with what that feels like. I think that partly because of the specialization that one finds in universities, where you have to be a major in one thing, for the first time you have students who were brought up as composing majors who didn’t play instruments, or didn’t keep up the performing.

BD: This is a big loss, is it not?

LL: Yes. I think a lot of them have lost touch with what it means like to actually have the experience of performing and to keep that up, and remember what it’s going to be like to have to learn and play that thing you’ve just written.

BD: Do you feel, though, that it’s a collaborative art between you and the performer?

LL: No.

BD: Not at all?

LL: No, I don’t. I don’t.

BD: You don’t want the performer to put anything into it?

LL: No. They should bring something to it, but it’s not like the performer is taking your piece and then layering over their own ideas on it. Not at all, because they might as well just rewrite the notes while they’re at it. To a composer, almost the whole dynamic framework comes before the notes. It’s almost like the notes are what are being filled in when you compose, not the dynamics and the articulations. A lot of performers do think that the notes are sacred, but beyond that they can sort of do anything they like to a piece. I think the act of performing and interpreting a piece is trying to come as close as one can to what was in the composer’s imagination. Now, more often than not, that’s not entirely clear, and you have to interpret and figure out what did the composer mean in a lot of respects. But no, I don’t feel it as sort of a collaborative thing where the performer is an equal.

BD: You don’t want each performance to be a carbon copy of the previous performance, do you?

LL: No, but one doesn’t want them to be wildly different. If a performance was an absolutely perfect performance, I would want them to be a carbon copy.

BD: Is there such a thing as an absolutely perfect performance?

LL: No, of course there isn’t! Of course there isn’t. But one is constantly reaching towards an ideal, and one would hope. You see, the best performers, to me, sublimate their personalities into the music and become a vessel for the music. To me, it’s the bad performers that impose their own personality onto the music and end up with something that is not what the composer intended, necessarily.

BD: There’s no happy marriage of both?

LL: Not really, because it’s a diametrically opposed attitude. Either you’re serving the music or you’re using the music as a vehicle for your own expression.

BD: So it’s black or white. There’s no gray in there? No Gray, Mr. Dorian?

LL: [Smiles at the pun] I’m talking about the attitude; I’m not talking about the final result. It is the idea behind it. Either you’re taking an attitude that you want to find what the composer meant and serve the music and serve the composer, or you’re out to express yourself through the music. When you are interpreting a composer, playing a composer’s music, there is always that leeway for how much of a retard to do. That’s where the personality of the performer can come in.

BD: And how fast is the allegro.

LL: Yes. But not,

“Oh, there’s a ritard written here and I don’t like it, so I’m not going to do it. I’m going to do it accelerando.” That’s the kind of thing I’m talking about.

BD: You say there’s no such thing as an ideal performance. Do you get real close on a recording because you have a chance to fix any mistakes?

LL: One can come pretty close. I have been extremely lucky in the performers who have done my music throughout my career since I graduated from Julliard. I’ve been very spoiled in the performers and orchestras who’ve done my music.

BD: Maybe what you need is one great big flop! [Both laugh]

LL: Well, I’ve had a couple of very bad performances that I’ve attended, so I do know what that’s like. But the majority have been very good experiences. So I’m usually happy.

LL: Well, I’ve had a couple of very bad performances that I’ve attended, so I do know what that’s like. But the majority have been very good experiences. So I’m usually happy.

BD: You don’t need to mention the specifics, but are there times when you’re ecstatic?

LL: Oh, yes! Absolutely, absolutely.

BD: Is the audience generally happy or ecstatic?

LL: I don’t know if I’m the proper person to say that, but in my experience, yes! I’ve had very good audience reactions, generally.

BD: Are we getting beyond the point where the audience is actually surprised to see the composer walk on stage?

LL: I think so. We’re actually in a very healthy time right now for contemporary American music because we’ve gotten over several decades where composers were operating from an ivory tower attitude, writing a kind of very academic, complex music that neither audiences nor musicians were very much interested in. A lot of composers of my generation have discovered that it’s not a dirty thing to be interested in audiences and write music that audiences can actually relate to. That is not to say that one panders to an audience, but to me, music, like all arts, is a form of communication, and if the language is so difficult for people to understand, that’s usually a problem with the language and not with the audience.

BD: Maybe this is why the critics are likening you to names that other people know, to get them so they’re not afraid of you. If they said you were like Schoenberg and Stockhausen, then audiences would not come in droves!

LL: Right, right, right.

BD: I’m just looking for a silver lining!

LL: I don’t know. One tries to figure things out, and I try to pay as little attention to those external things, and concentrate on the music as much as possible.

BD: I assume you get a number of commissions. How do you decide yes, I’ll take this one; no, I’ll turn that one aside?

LL: I’ve been writing on commission since I graduated from Julliard, which was in 1987. I am basically doing that full-time; I don’t teach.

BD: Not at all?

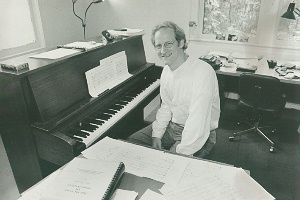

LL: Not at all. I just compose, and every now and then do a little performing, or now more and more, conducting as a break from the composing, because it’s actually difficult to keep churning out music, one piece after another.

BD: [With a sly nudge] We can’t expect you to be an automaton, just grinding it out all the time??? [Both laugh]

LL: No, no! But I’ve been very lucky in that the commissions have been quite steady. I haven’t turned down many commissions. They’re not pouring in at an un-doable rate...

BD: But you must look at each one and decide.

LL: Yes, you have to.

LL: Yes, you have to.

BD: So how do you make the decision?

LL: Maybe it’s a performer who you don’t think is terribly good, so you’ll politely say no; or it’s just a kind of piece that you’re not interested in writing. Every now and then you get a very odd request for a commission, and sometimes that can spark you because it’s so interesting. For instance, I had a commission for a piece for solo bass koto, the Japanese instrument. Then another commission was for orchestra and five Japanese drums — actually the Koto Ensemble, the Japanese drummers. Those were two commissions where I first thought, “Oh, that’s odd.” But then I thought, “Oh, that’s an interesting challenge.”

BD: And you were up to it?

LL: Those were two commissions that I did do eventually. I’ve had an awful lot of flute commissions because my music has gotten well known in the flute world.

BD: So when someone comes to you with a flute commission, do you try to nudge them to play what you’ve already written, rather than constantly coming up with something new?

LL: If it’s a commission that I’ve already written for that combination, I won’t do it. Actually I have written my last flute piece for a long time. I don’t intend to write another one for a while, because I’ve written for flute in different combinations and different flutes. Actually, my latest flute work is being premiered today at the flute convention in Arizona.

BD: Why aren’t you there?

LL: [Matter-of-factly] Because I’m here!

BD: [Laughs] If you could, would you want to clone yourself so you could be at all your performances?

LL: Not necessarily. Special performances one always wants to be at. Premieres one would like to be at.

BD: If you could, would you want to clone yourself so that you could go to performances and also could continue to compose?

LL: I’m not that obsessive about what I do that I’m that concerned with it. One can only do so much in one’s lifetime, and you just have to accept the fact that you can’t do everything, after a certain point.

BD: Don’t you want to have a hundred and four symphonies to your credit?

BD: Don’t you want to have a hundred and four symphonies to your credit?

LL: No, no, I don’t. First of all, I don’t think I have a hundred four symphonies in me. It’s funny because certain other composers accuse me of being wildly prolific, which I don’t feel I am.

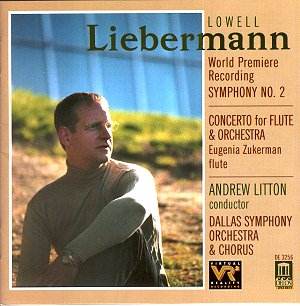

BD: You feel you’re moving at your own pace? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interview with Andrew Litton.]

LL: I feel I’m moving at my rather slow pace. I’m very impatient with myself. I feel as if I waste a lot of time as a composer. I feel, basically, like I’m a very lazy person. Then other people say, “My God, you’re so prolific! You’ve written sixty-one opus numbers at your age!”

BD: It is quite a lot for a little more than a decade.

LL: Well that would be stretching it because I wrote my Opus One when I was about fifteen. So it is a little more than two decades.

BD: Okay. But still, sixty one opus numbers is quite high!

LL: I recognize it’s a respectable amount of music to be written, and I could die today and feel at least I’ve accomplished something.

BD: Are you proud of all of them?

LL: Not equally proud of all of them, maybe, but there are no pieces that I’m ashamed of, because I would have withdrawn them a long time ago.

BD: That’s good that you still like your early works.

LL: Yes, and that’s an example where I would not want to go back and revise them, even though I recognize that some of them are flawed. I’d rather have my Opus One stand as a piano sonata that I wrote when I was fifteen, than try and go back and rewrite it when I’m really a different person and a different composer, It would just be a hybrid, then, that was neither here nor there. I’d much rather spend my energies writing new pieces than going back and revising.

BD: Is each piece a little progress for you?

LL: I don’t know about this concept of progress in art. I think that’s a big cliché of the twentieth century. [Laughs] In fact, I was having lunch with a writer who was putting forth the idea that it was a Marxist cliché of the twentieth century!

BD: [Laughs] Then I’ve got to revise my thinking!

LL: I think music history has neatened up everything in retrospect to where it now seems that the musical continuum has been one smooth progression. I don’t think that is the case.

BD: I see it in fits and starts.

LL: It’s in fits and starts, and then there are composers who don’t quite fit in, or were considered conservative or even retrogressive in their day. Historians like things tied up in neat boxes, and like to see charts and graphs. I don’t think much of the concept of artistic progress, because I think it’s a sort of fluid evolution. What is the concept of progress

— that what’s being done today is better than what was being done in Bach’s era or Beethoven’s era.

BD: Then let me revise the question slightly. Is each piece that you do a little growth for you as a composer?

LL: I would hope. I do recognize the couple of pieces that maybe I didn’t have as much time as I wanted to spend on. So maybe in that respect they’re not as growing, or as thoroughly investigating something as I would want to be.

BD: When you sit down to start a piece, do you know how long it will take you to accomplish the compositional task?

LL: Usually it takes as long as I have to write it. I really only get pieces finished because I have deadlines. If I have a month to write a piece, I’ll write it in a month. If I have a year to write a piece, I’ll think about it for eleven months and then write it in a month. I tend to be very dissatisfied with whatever I’m doing at the moment.

BD: You can’t self-impose an earlier deadline?

BD: You can’t self-impose an earlier deadline?

LL: Oh, that never works! I can’t fool myself. So if I have an unlimited amount of time, I just keep hacking at the material, not being satisfied, until, you know, forever. The joy of deadlines is that you just have to grip yourself and say, “I’ve got to get this piece finished!” So you sort of just grit your teeth and force yourself ahead.

BD: Are the ideas always there?

LL: It depends. The idea is usually there, but then how it gets worked out can sometimes be the tough part. When I start a new piece, it does take a long time to get the idea and to decide what I want to do with it. Each piece is different. Sometimes it can be three notes, sometimes it’s a theme, sometimes it’s a concept. And you never know; each piece is different. That’s one of the things. I have a great belief in variety in art, not only variety from one work to the next, but also variety within the piece itself. One looks at a lot of modern art, or a lot of artists, or composers, who just do one thing; they have their shtick. They might do solid color paintings, and there’s really no growth or difference between any of the works. So that variety is something I would like to think happens in my music.

BD: You have the variety on your palette to choose. Is your palette set, once you get out of school, or does your palette get bigger with time?

LL: I would hope it’s continuously expanding... or not necessarily expanding, but changing because one changes as a person. Hopefully there’s some relation between one’s growth as a person and the growth of one’s art, not that art should be autobiographical.

BD: We’re kind of dancing around it, so let me hit you with the big question. What is the purpose of music?

LL: [Laughs] Oh, dear! I hate those kinds of questions because it’s very difficult for me to give a sincere answer without sounding very maudlin and sort of sentimental and almost naïve. It also ties in with my belief why so many damaged people become artists, which is that one tries in one’s art to create almost a perfect world, this perfect artificial world. In my own music, I have a firm belief in beauty in the art. I don’t believe the purpose of art is to twist one’s face in the negative aspects of one’s culture or life. For me, art has almost a moral purpose, that it should point the direction to a better way.

BD: It sounds like it’s very optimistic and uplifting.

LL: Yes, it is. I don’t really know what the purpose would be otherwise. That’s not to say that one doesn’t have sad music or depressing operas, but somehow, if it’s a great work, you feel renewed and refreshed, and it somehow points in a better direction. And I would like to think that my music helps to lift one out of the mire that contemporary life is.

BD: Because I’m a very optimistic person, I look for this in music.

LL: I can tell! You look like an optimistic person!

BD: [Laughs] Thank you! I take that as a compliment!

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you want to be at this age?

LL: I don’t think one is ever at the point one wants to be. One always wants more. What I would really like is just to have the security

— financial and otherwise — to really accept not only just the commissions I want to do, but the number I want to do each year, and really be in a position to be picky and choosy; to be able to write my music without having the day-to-day worries.

BD: I assume you’re getting toward that.

LL: Oh, yes. I certainly am.

BD: You’ve written chamber music, you’ve written orchestral works, you’ve written an opera. When you’re working on one piece, do you ever get an idea that you think, “Oh, that would be good, but not in this string quartet, but in a song”?

LL: Yes, sure. That does happen.

LL: Yes, sure. That does happen.

BD: Do you save that idea?

LL: Yes. I’ve got quite a stack of sketches of just little fragments; sometimes it’s just a little figure of a couple of notes.

BD: Do you refer to those often?

LL: Usually when I’m beginning a new piece I look through those sketches to see if there’s anything I want to use. There usually isn’t, and I usually end up just writing new material. So I have this stack of sketches, and the bottom pages are getting progressively browner as there are always new ones being put on top.

BD: Eventually you’ll come back to them, though?

LL: Eventually, eventually.

BD: Or maybe not?

LL: Or maybe not. [Both laugh]

BD: Does it surprise you that the new ideas are usually there?

LL: It’s different with each piece. Sometimes you really have to sit down and force an idea out of your head, and other times it just comes to you. The main theme of my Flute Concerto was written on a cocktail napkin at a bar after a couple of margaritas. That sort of thing usually almost never happens. It’s very rare.

BD: Did that one hold up later under the light of sobriety?

LL: Yes, it did. And I still have that cocktail napkin, actually.

BD: Do the ideas generally come from your head or do they come from your heart?

LL: Let’s not get into that debate! My head and my heart are not separate. They’re one bound whole.

BD: That’s the way to look at it, absolutely! Then let me ask, is the music that you write more art or more entertainment, and where is the balance?

LL: I guess one would have to define the difference between art and entertainment. To me, it’s more of a business thing. Entertainment is for money. One creates entertainment to make money. Art is theoretically and hopefully for a higher purpose. Entertainment to me is a much more passive thing for the audience. The audience members are passive, whereas art implies some kind of active, intellectual participation in what’s going on.

BD: It sounds like you demand that of your audience.

LL: Well, hopefully. And the best music, whether you’re talking about Mozart or Bach or Beethoven or Stravinsky or Bartók or Shostakovitch...

BD: [Interjecting] Or Lowell Liebermann?

LL: Well, I’d hopefully like to be in amongst those names. Hopefully, the best music can be appreciated on many levels by many different people of varying sophistication. One can listen to a Mozart piece for the pretty tunes, but then one can also listen in a more intellectual way and appreciate the construction and what’s going on technically. That’s what I do try and achieve in my music. I hope that there is a firm intellectual structure going on, that hopefully continues to reveal itself with repeated listenings. It can sometimes be a very complex structure, but on the surface it has something of beauty and of interest and of atmosphere that will capture the listeners and draw them in. When it comes down to it, I firmly believe in the need for a good tune, and that that is also one of the most difficult things for a composer to do. That sounds quite crass, but it’s true.

BD: Not really crass at all. This is something needed, especially as we’re getting back to music that can be listened to by audiences. Making a good tune is extremely difficult, and yet very rewarding when it’s done.

LL: Yes. In fact, I was reading an issue of one of those terrible glossy British classical music magazines, and there was a young British composer who was being interviewed. He actually said that he was worried about his music being too tonal, until a friend of his challenged him to sing the main theme of his piece. He couldn’t, and was relieved!

BD: That’s very sad!

LL: Right, when a composer says that proudly, that’s very sad! That music has to be so contorted that it’s unmemorable and un-performable.

BD: I think that’s probably just an outgrowth of wanting to be different for different’s sake.

LL: Well, it’s a fear, and one sees that in the British music scene especially. Although they pretend to be on the forefront of what’s going on, they usually lag behind the trends on what’s going on in America. And they have such a complex about being intellectual and being on the cutting edge and not being conservative.

BD: But I think audiences are crying for this.

LL: Yes, they are. They are.

BD: I’m glad that you are serving that end.

LL: It’s very gratifying to be sitting in the audience at one of my pieces, when there are people sitting next to you who don’t know who you are, and listening to their comments.

BD: Are they surprised when you walk up onstage and take a bow?

LL: Sometimes, and that can be very gratifying when you get really sincere reactions from people, and they like it!

BD: There’s where you should have your clone, but one that doesn’t look like you! It could wander around undetected!

LL: Well, one could try disguises. On the other hand, that might be dangerous! [Both laugh]

BD: You look vaguely like a TV actor.

LL: I have had so many people say that to me lately! Actually I’ve been mistaken for three or four different actors in the course of my life. At this flea market I used to go to, I got into a half-hour argument with one of the dealers who was convinced I was Jeff Daniels, who I don’t think I look at all like, really! But now I keep hearing that I look like the actor who’s in “Caroline in the City.”

BD: You’re just cursed with that kind of a face! [Both laugh again] One last question. Is composing fun?

LL: It can be. It can also be very difficult, very frustrating and very agonizing because when you are composing, you really are wrestling with aesthetic issues, and if you’re really concerned about what you’re doing, they become moral issues. And it’s very hard work and very concentrated. It’s solitary work, but yes, it can be fun. The work that I wrote that was the most fun was actually the opera, even though physically and in terms of hours it was the most arduous task.

BD: I wonder if it’s because of the text.

LL: The text removes so much of the blindness that you have when you’re creating a piece. You usually have to create the format out of nothing, but when you have your libretto, you always know where you’re going. It doesn’t necessarily give you the musical form, but it gives you the whole emotional framework. In that way, it’s this very freeing thing to be working with an opera. And it’s very different than writing a song, for some reason. A song is usually such a short form and you have to be very focused; the emphasis becomes on the moment-to-moment thing rather than the large-scale sweep. It’s a very different thing. When you have the big, grand sweep of an opera, you know this scene is about this and you’re going to that. Somehow that’s a very liberating thing.

BD: I would think it would be like having a guide, but not a dogma.

LL: Yes.

BD: I wish you lots of continued success!

LL: Thank you!

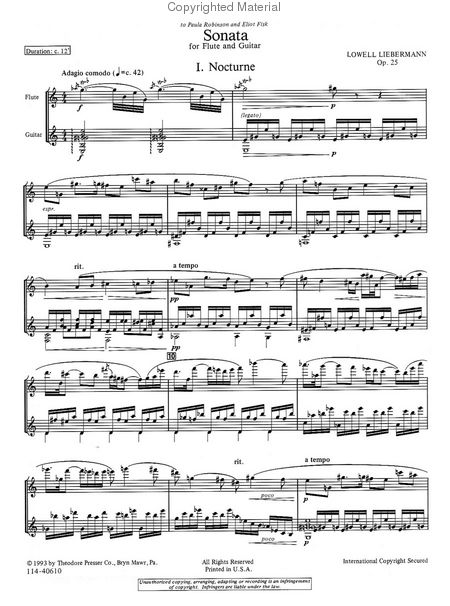

Lowell Liebermann is one of America's most frequently performed and commissioned composers. Described by the New York Times as "as much of a traditionalist as an innovator," Mr. Liebermann's music is known for its technical command and audience appeal. Multiple recordings of many of his works attest to the enthusiasm shared by performers and listeners for his music: the Sonata for Flute and Piano has been recorded sixteen times to date; the Gargoyles for piano eleven times; and the Concerto for Flute and Orchestra is available on four different releases.

Mr. Liebermann's second full-length opera, Miss Lonelyhearts, set to a libretto by J.D. McClatchy after the novel by Nathanael West, was premiered in April, 2006 at Lincoln Center’s Juilliard Theatre, under the baton of Andreas Delfs. The opera was commissioned by the Juilliard School to celebrate its 100th Anniversary. A reduced orchestration version of Mr. Liebermann’s first opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray, was premiered to great critical and popular acclaim by Center City Opera Theater at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia in June, 2007. Piano Concerto No. 3 was commissioned for pianist Jeffrey Biegel by a consortium of eighteen American and international orchestras, and received its premiere in May, 2006 with the Milwaukee Symphony conducted by Andreas Delfs. And in September of that year, the chamber ensemble Concertante premiered the Chamber Concerto No. 2, Op. 98 for Violin and String Quartet (which it also commissioned from Mr. Liebermann) with violinist Xiao-Dong Wang.

Recent seasons have seen the premieres of many other major Liebermann compositions. His Concerto for Orchestra was commissioned and premiered by the Toledo Symphony under the direction of Grant Llewellyn, and later recorded by Llewellyn with the BBC Symphony for CD release. Stephen Hough and the Indianapolis Symphony performed Liebermann's_Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini_, which the orchestra commissioned to celebrate Raymond Leppard's farewell concert as conductor. Charles Dutoit and the Tokyo NHK Symphony gave the world premiere of Variations on a Theme of Mozart, commissioned to mark the orchestra's seventy-fifth anniversary, and also recorded by the BBC Symphony. The New York Philharmonic and principal trumpet Philip Smith presented the premiere of Mr. Liebermann's Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra, which the Wall Street Journal described as "balancing bravura and a wealth of attractive musical ideas to create a score that invites repeated listening. [Liebermann] is a masterful orchestrator, and just from this standpoint the opening of the new concerto is immediately arresting," also noting that the "rousing conclusion brought down the house."

In 2001, Mr. Liebermann was awarded the first American Composers' Invitational Award by the 11th Van Cliburn Competition after the majority of finalists chose to perform his Three Impromptus, which were selected from works submitted by forty-two contemporary composers. In an interview with newscaster Sam Donaldson, Van Cliburn himself described Mr. Liebermann as "a wonderful pianist and a fabulous composer." Mr. Liebermann's_Symphony No. 2_ was premiered in February, 2000 by the Dallas Symphony and Chorus, under the direction of Andrew Litton. TIME magazine wrote, "now brazen and glittering, now radiantly visionary, the Liebermann Second, a resplendent choral symphony, is the work of a composer unafraid of grand gestures and openhearted lyricism." Maestro Litton and the DSO recorded the symphony and the Liebermann Concerto for Flute and Orchestra on the Delos label, with Eugenia Zukerman as soloist. In February, 2001, the Dallas Symphony gave the New York premiere of Mr. Liebermann's Piano Concerto No. 2 at Carnegie Hall, with Stephen Hough as soloist. Stephen Wigler of the Baltimore Sun found the concerto to be "perhaps the best piece in the genre since Samuel Barber's concerto." John Ardoin, of the Dallas Morning News, described the work as "more than a knockout; it is among the best works of its kind in this century." Stephen Hough's recording of the concerto – conducted by the composer – received a 1998 Grammy Award nomination for Best Contemporary Classical Composition.

In May, 1996, Mr. Liebermann's opera based on Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray was premiered at L'Opéra de Monte-Carlo to great popular and critical acclaim. This commission was the first by an American composer in the company's history. After the opera's American premiere in February, 1999 at Milwaukee's Florentine Opera, the New York Times commented, "musically and dramatically, Mr. Liebermann's work is effective; as a first opera, it is remarkable."

James Galway has commissioned three works from Mr. Liebermann: the Concerto for Flute and Orchestra, the Concerto for Flute, Harp and Orchestra, and Trio No. 1 for Flute, Cello and Piano. Mr. Galway premiered the Flute Concerto in 1992 with the St. Louis Symphony and the double concerto with the Minnesota Orchestra in 1995. That same year, Mr. Galway performed the Flute Concerto with James Levine and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Mr. Galway recorded both works, along with Mr. Liebermann's Concerto for Piccolo and Orchestra, for BMG, with Mr. Liebermann conducting.

Mr. Liebermann acted as Composer-in-Residence for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra until 2002. He filled the same role for Sapporo's Pacific Music Festival and for the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. His tenure in Saratoga led to the commission of the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, which was premiered by Chantal Juillet and the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Charles Dutoit.

Recent recording releases on the KOCH and Arabesque labels include Mr. Liebermann's complete piano music performed by David Korevaar, his complete chamber music for flute, and the complete songs for tenor and piano with the voice of Robert White, and Mr. Liebermann at the piano. Additional recordings of Mr. Liebermann's music are available on Hyperion, Virgin Classics, Albany, New World Records, Centaur, Cambria, Musical Heritage Society, Intim Musik, Opus One and others.

Orchestras worldwide have performed Mr. Liebermann's works, including the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, l'Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, the Tokyo NHK Symphony, l'Orchestre National de France, and the symphonies of Dallas, Baltimore, Seattle, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Minnesota. Among the artists who have performed Liebermann's works are James Galway, Charles Dutoit, Stephen Hough, Jeffrey Biegel, Kurt Masur, Joshua Bell, Hans Vonk, Steven Isserlis, Andrew Litton, Susan Graham,David Zinman,Jesús López-Cobos, Paula Robison, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Steuart Bedford, and Jean-Yves Thibaudet.

Mr. Liebermann maintains an active performing schedule as pianist and conductor. He has collaborated with such distinguished artists as flautists James Galway and Jeffrey Khaner, violinists Chantal Juillet and Eric Grossman, singers Robert White and Carole Farley and cellist Andrés Díaz. He performed the world premiere ofNed Rorem's Pas de Trois for Oboe, Violin and Piano at the Saratoga Chamber Music Festival. In 2002 he made his Berlin debut performing his Piano Quintet with members of the Berlin Philharmonic. On February 22, 2006, Mr. Liebermann's 45th birthday, the Van Cliburn Foundation presented a highly successful all-Liebermann concert as part of their "Modern at the Modern" series, with the composer at the piano and featuring the premiere of Liebermann's Sonata for Cello and Piano, Op. 90. Also in 2006, Mr. Liebermann was invited to perform the complete Mozart sonatas for violin and piano with violinist Eric Grossman at the Detroit Art Institute to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth.

Lowell Liebermann was born in New York City in 1961. He began piano studies at the age of eight, and composition studies at fourteen. He made his performing debut two years later at Carnegie Recital Hall, playing his Piano Sonata, Op.1, which he composed when he was fifteen. He holds Bachelor's, Master's, and Doctoral degrees from the Juilliard School of Music. Among his many awards is a Charles Ives Fellowship from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Theodore Presser Company is the exclusive publisher of Mr. Liebermann's music.

For more information, please visitwww.lowellliebermann.com

Current as of August 2007

Theodore Presser Company

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on August 15, 1998. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1999, and on both WNUR and Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2009 . This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2009. It has also been included in the internet channel Classical Connect.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.