David Zinman Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

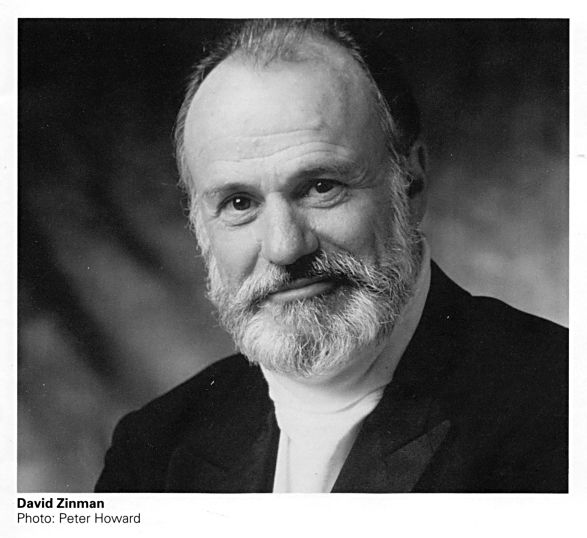

Conductor David Zinman

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

After early violin studies at the Oberlin Conservatory, David Zinman (born July 9, 1936 in New York City) studied theory and composition at the University of Minnesota, earning his M.A. in 1963. He took up conducting at Tanglewood, and then worked in Maine with Pierre Monteux from 1958 to 1962, serving as his assistant from 1961 to 1964.

Zinman held the post of tweede dirigent (second conductor) of the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra from 1965 to 1977. He was the principal conductor of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra from 1979 to 1982.

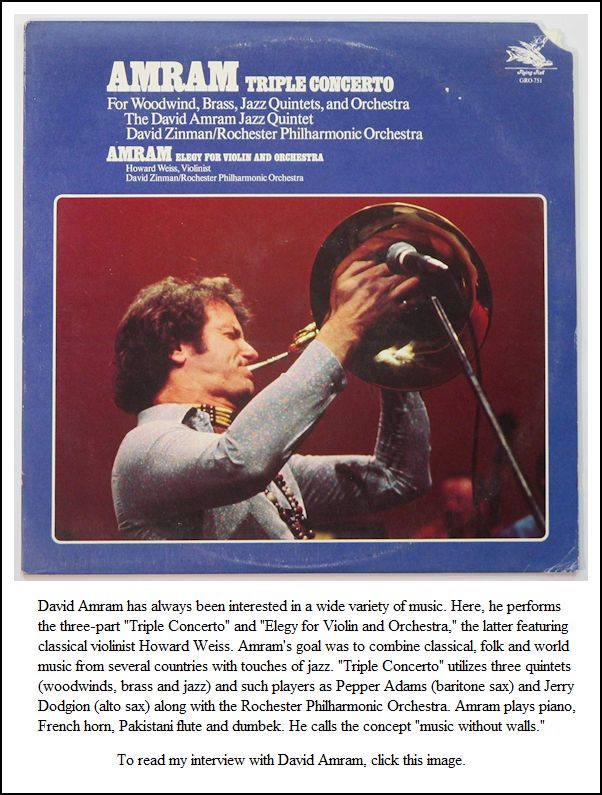

In the US, Zinman was music director of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra from 1974 to 1985. With the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, he was principal guest conductor for two years before becoming the orchestra's music director in 1985. During his Baltimore tenure, he began to implement ideas from the historically informed performance movement in his interpretations of the Beethoven symphonies. At the end of his Baltimore tenure in 1998, Zinman was named the orchestra's conductor laureate. However, in protest at what he saw as the Baltimore orchestra's overly conservative programming in the years since his departure, he renounced that title in 2001. In 1998, Zinman was the Music Director of the Ojai Music Festival alongside pianist Mitsuko Uchida. In 1998, he was appointed music director of the Aspen Music Festival and School, where he founded and directed its American Academy of Conducting until his sudden resignation in April 2010.

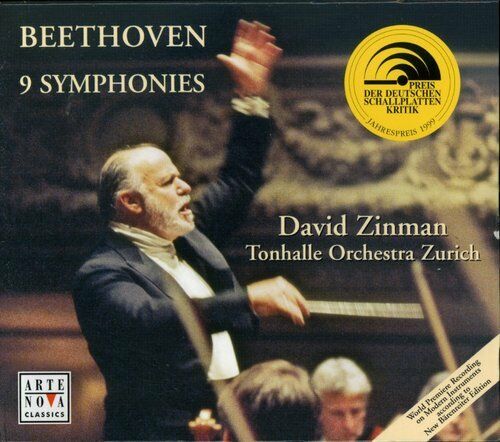

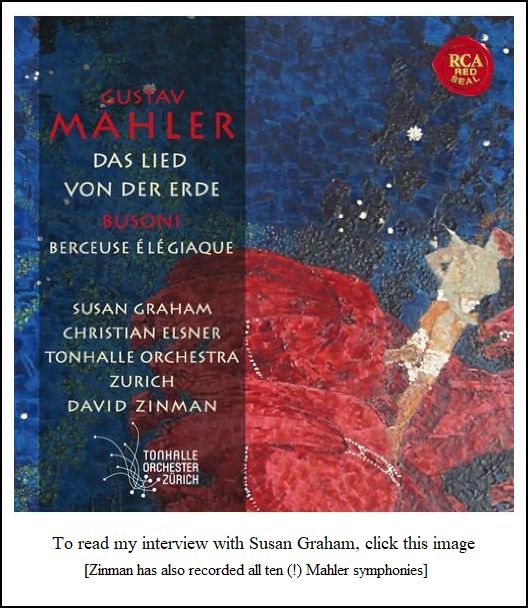

Zinman became music director of the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich in 1995. His innovative programming with that orchestra includes a series of late-night concerts, "Tonhalle Late", which combine classical music and a nightclub setting. His recordings for Arte Nova of the complete Beethoven symphonies [_shown below_] were based on the new Jonathan Del Mar critical edition and was acclaimed by critics.

He has subsequently recorded Beethoven overtures and concertos with the Tonhalle. He conducted the Tonhalle Orchestra in its first-ever appearance at The Proms in 2003. In 2009, he conducted the Tonhalle in the soundtrack for the feature film 180° - If your world is suddenly upside down. He concluded his Tonhalle music directorship on July 21, 2014 with a concert at The Proms.

Zinman also conducted for the soundtrack of the 1993 film version of the New York City Ballet production of Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker. His 1992 recording of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony no.3 with Dawn Upshaw and the London Sinfonietta was an international bestseller. In January 2006, he received the Theodore Thomas Award presented by the Conductors' Guild.

Note: Links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

Among his vast array of guest engagements, David Zinman has led the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on several occasions, both downtown and in the summer at the Ravinia Festival. Chicago has also figured prominently in his career when he was Principal Conductor of the Grant Park Music Festival for several seasons in the 1980s.

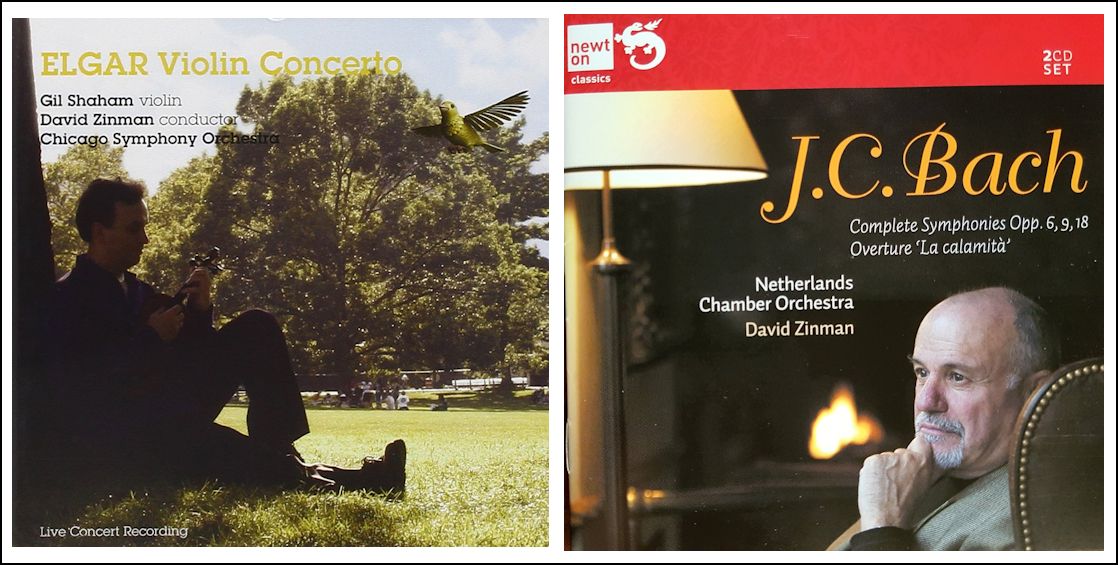

He has made many recordings over the years, and those which I have selected for this website presentation were chosen because they had photographs of the conductor from different periods, or they included performances by other guests whom I have interviewed.

We arranged to meet in his dressing room, backstage at Orchestra Hall just prior to the second of four concerts with the CSO, in February of 2000. On the program were Two Portraits of Bartók, with Samuel Magad, one of the concertmasters of the CSO as soloist,

the Piano Concerto #2 of Beethoven played by Radu Lupu, and the Symphony #5 of Dvořák.

Zinman was very candid with his responses, and laughed good-naturedly several times during the conversation . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: I assume that music is still your favorite subject after all these years?

David Zinman: I think so.

BD: That’s good. Now you’ve just arrived, and you’re going to be conducting a concert in an hour. Is everything all prepared so that you know exactly the way it’s going to go, or is there something up your sleeve to make it sparkle tonight?

Zinman: [Chuckles] I don’t think anything can be totally planned. There’s always something that happens at the concert that’s very different from what you rehearse. You know it might be better, or it might be worse. It might be much more exciting. Last night we had a concert, tonight we have a concert, so it varies.

BD: Is each one unique?

Zinman: Each one is very unique. Also, the dynamic with the audience is quite different each night. There’s a different type of audience, and we feed off of that.

BD: Do you feel it behind you?

Zinman: You feel it behind you, and now, in this hall you can see it in front of you as well.

BD: Does that rattle you at all to have part of the audience in front of you?

BD: Does that rattle you at all to have part of the audience in front of you?

Zinman: No. A lot of European halls have that, including my own hall in Zurich.

BD: Is that a good thing, a bad thing, or just a thing?

Zinman: I like it, and I know the people that sit behind the players like it too, because they get another perspective of what’s going on.

BD: Are they ever surprised by your facial expressions, or what you do?

Zinman: That’s the thrill of it for them, essentially that they can see the expression on the face of the conductor... assuming he has one! [Both laugh]

BD: Should you have one?

Zinman: Yes, you have to have an expression on your face. Whatever comes out of you as a conductor has to show on your face.

BD: Then what comes out of you shows in your face and in your hands?

Zinman: That’s right.

BD: What is it that goes into you to make those expressions?

Zinman: The music goes into you. It’s a direct expression of the music, so essentially what’s happening is you are hearing what is going to come out, and you are trying to show that. Then, you’re also reacting to what is coming out.

BD: You have a score in front of you. Is it the notes on the page, or is it mingled with the music in your heart?

Zinman: It’s all kinds of things. I can’t analyze it in any one way. You have in your mind an ideal presentation of the music, and sometimes it changes from day to day. But essentially that’s what you’re trying to do. If you have a piece that begins in a certain way, already your mind is telling you the gesture that you’re making.

BD: So, the music begins. You don’t begin it?

Zinman: That’s right, yes. The music begins.

BD: Is there only one way to play each piece of music?

Zinman: No, there are millions of ways. That’s what makes it interesting.

BD: Is there only one way for you to play it?

Zinman: No.

BD: Your interpretation changes?

Zinman: The interpretation changes, and over the years there’s a vast difference. If you’re accompanying someone, like in a Beethoven concerto which we’re doing tonight, his interpretation affects what you’re doing. It is a lot of give and take. What’s very wonderful about this business is that it’s not going to always be the same. You’re not always going to think the same way about the music, and you’re always discovering new things.

BD: Are you ever surprised by what you discover?

Zinman: Sometimes, yes.

BD: Good or bad?

Zinman: Usually they are good surprises.

BD: You have this vast array of symphonic literature to choose from. How do you decide which pieces you’re going to spend your time learning and understanding, and which pieces you’ll set aside?

Zinman: I have a rather broad repertoire, so I’m always very interested in new music, and in music that I don’t know, and one keeps playing the standard repertoire

— nine Beethoven symphonies, four Brahms symphonies, four Schumann symphonies, six Tchaikovsky symphonies, nine Schubert symphonies, the list goes on and on. But also, throughout my life I started doing all the Sibelius symphonies, and all the Nielsen symphonies, and Elgar, and then Vaughan Williams. So it grows, and you begin to get an interest in each one of these composers. Having lived in Holland, and now in Switzerland, you get interested just a little bit in what happens in Holland and then in Switzerland, and in Dutch music of the past and Swiss music of the past as well. Of course, there is American music, including the music that’s being written today.

BD: You’re an American conductor working in America and Europe. Do you make sure that you bring American music over there?

Zinman: I have a permanent job in Switzerland, and they don’t appreciate it if I bring too much American music there. I have to get interested in what’s happening in Switzerland. But certainly, when I was music director for American orchestras, that was my primary thing, and my mission was to play as much good American music as I could.

Zinman: I have a permanent job in Switzerland, and they don’t appreciate it if I bring too much American music there. I have to get interested in what’s happening in Switzerland. But certainly, when I was music director for American orchestras, that was my primary thing, and my mission was to play as much good American music as I could.

BD: I want to pounce on the word ‘good’. What is it that makes a piece of music good, or perhaps even great?

Zinman: It has to appeal to me. That’s the first thing, and through that I can make it appeal to the audience. But it has to be communicative, and sometimes it takes a long time to discover that communication. But when I am convinced, the audience will be convinced, and the orchestra especially. I’ve gotten to know a lot of composers personally, and it’s nice to know them and their pupils, and to see the line music has taken over the years. Now we’re in a very good period for American composition and American composers, so it’s of interest to do American music.

BD: What about this period makes it good

— is it because they’re writing more tonal music, more accessible music?

Zinman: I don’t know if it’s more accessible or tonal. They just have very good chops, as we say in the jazz field. They know their craft. They know it much better than perhaps in the

’60s and ’70s, although I’m sure those composers knew their craft very well. It just didn’t appeal to people as much as it does now. The younger composers today have really a wonderful technique, a good way of communicating with an audience, and that’s very important. Certainly composers like Corigliano, Rouse, Harbison, Torke, Kernis, and people like this are writing accessible music, but they’re still writing in their own styles. So, certainly it’s an interesting time.

BD: Is it that they have a better grasp of what really is a symphonic piece of music?

Zinman: Yes, and they have the whole past to draw upon. They’re not trying to do anything specifically new. They’re trying to synthesize what’s gone before them, which all composers have done in the past. I don’t think Bach decided suddenly he was going to write new music. In fact, he was considered a synthesis of what had gone before him. Certainly, composers like Beethoven, who moved in a new direction, still had one foot in the past when they were writing. The same thing is true even with Wagner, and other people who were considered revolutionaries. They couldn’t have been rebellious without Beethoven, and that’s the key

— music has a continual line, and it just doesn’t break off somewhere. If people think that The Rite of Spring was a new departure, [laughs] well, they have the wrong thought, because it certainly was an extension of what Rimsky-Korsakov was doing.

BD: If they think it’s a new departure, maybe were they missing the previous years?

Zinman: Yes, but nowadays we can look back on it, and see where it comes from essentially.

BD: Is it your responsibility, as an orchestral conductor, to know and understand all of this literature, even if you don’t conduct every piece?

Zinman: Yes, I think so. Since it’s my interest, I do a lot of reading about music, and studying music, and since I studied as a composer, I know how music is written. But what’s very interesting for me is that I have fourteen books about Beethoven in my library, but it never ceases to fascinate me what’s going on. For instance, with a composer that we’re doing tonight, Dvořák, there’s a tremendous amount of repertoire that’s never heard.

BD: We seem to be moving backwards. We did the Ninth Symphony too many times, then we went back to the_Eighth_, and now we’re get tired of that, so we go back to Seven, and you’ve gone back to Five.

Zinman: Right! But he wrote a tremendous amount of orchestral music, of which I would say, only twenty per cent is played.

BD: [Enthusiastically] Plus a pile of string quartets, and piano music, and other works.

Zinman: Yes, that’s right.

BD: Is this what it takes to be a good symphonic composer

— to also write quartets and piano music, and violin pieces?

Zinman: Composition is total. There are very few composers who only wrote operas. Even Verdi wrote a string quartet...

BD: Right, for amusement while waiting for rehearsals.

Zinman: Yes. [Both laugh] It’s a beautiful string quartet, but at the time of Beethoven and Schubert and Brahms, the finest musical amateurs were quartet players, and people who made music in the home. So some of their finest music was written for those people who would really appreciate and understand what the composer was doing.

BD: Are we getting back to this idea of Hausmusik [literally, music made in the house]?

BD: Are we getting back to this idea of Hausmusik [literally, music made in the house]?

Zinman: Well, I don’t think there will ever be the kind of Hausmusik that went on at the turn of the century, or in the beginning of the century. We have our own house music because we have recordings.

BD: Is the flat plastic disc the replacement of Hausmusik?

Zinman: In a sense, yes, to the detriment of people’s musical education. It is much easier now to put on a record than to learn how the learn how to play the piano. [Both laugh]

BD: [With a gentle nudge] But you continue to make records...

Zinman: Of course! Records are fun, and they teach a lot. It is our way of putting down what we thought about the music at that time. I don’t say it’s the be-all and end-all of everything. It’s a good way of understanding how people played in the past, and are playing now, and whatever will happen in the future. I think it’s going to develop in a different way soon.

BD: How so, or do you know?

Zinman: Technology always changes the way recordings are made, and someday it will be within people’s means to have surround-sound in their house, and then the repertoire will all be made in surround-sound. So, we’ll get a chance to re-record some of the repertoire, and certainly a piece like the Berlioz Requiem, or the Mahler Second Symphony in surround sound will make a tremendous impression.

BD: Will we be able to put the home-listener in the conductor’s spot?

Zinman: Yes, or at least in the middle of the hall, where you hear things coming from all around you.

BD: Now there is one other thing in the technical vein. There’s an idea that you can, at home, change the balance, or change the speed, or change the interpretation.

Zinman: Maybe that will happen. I don’t know. It depends on how the music is recorded. Still I think the best recordings that we make at the present time are two-track recordings, with the balancing done right on the spot, and not manipulated after. That gives you the most realistic way, the most interesting way of performing music. However, Glenn Gould felt the other way, and there’s a lot of manipulation that can be done, and now, with digital techniques, you can lower or raise the pitch, and keep the speed the same. So, a lot of fixing can be done as well.

BD: Is there a chance that a recording can get too perfect?

Zinman: There’s no such thing as perfection.

BD: But you strive for it?

Zinman: You strive for it. I strive to bring out the meaning of a piece of music, and whatever that is for me. I don’t only strive for technical perfection. Some of my favorite records actually aren’t that perfect, or are a little bit on the sloppy side, but that’s not what interests me. If you listen to one of Furtwängler’s recordings of the Fifth Symphony, the beginning is not together. Well, so what?

BD: But the sweep of the work is there?

Zinman: Yes, and that’s what important.

BD: Do you conduct the same in the recording studio as you do in the concert hall?

Zinman: No. You have to first train the orchestra not to overdo. In a concert, people play for the back of the hall. My soloists play for the back of the hall, and so they tend to force a little more. You tend to play louder, and you tend to go for effect a little bit more. On recordings you have to see where the high point is. You have to make sure that everything is in balance. The sound has to be good, the ensemble has to be super, and orchestras have to play in a slightly different way. The speeds also have to be different, because in a live concert you can get away with enormously slow tempi. On a record you can’t, because it just doesn’t support it. There isn’t the atmosphere.

BD: You’re almost being handcuffed by the technology?

BD: You’re almost being handcuffed by the technology?

Zinman: Of course! But if you conduct a ballet, you’re handcuffed by the dancers. [Both laugh]

BD: I assume you’ve conducted a number of ballets?

Zinman: Yes, I have.

BD: Have you conducted opera, too?

Zinman: Yes.

BD: Do you like working with the stage in front of you, rather than just a group of musicians bowing, and blowing?

Zinman: Yes, but it’s not a very ideal world, and a lot of things happen. There are occasions when you don’t agree with the staging, and that’s very frustrating. Then there are always people getting sick, and being replaced at the last second without a rehearsal. It’s a bit like being a fireman.

BD: [Gently protesting] But aren

’t some of the fires spectacularly beautiful.

Zinman: Oh, yes, that’s true.

BD: So you have to control the fire, rather than just extinguish it?

Zinman: Yes, but when singer jumps forty bars, it’s dangerous.

BD: You’d have to get the whole orchestra to catch up.

Zinman: That’s right.

BD: I hope you haven’t had that happen too often...

Zinman: No, but it does happen.

BD: Are you more in control when it’s purely a symphonic concert?

Zinman: Yes, definitely.

BD: Is that more rewarding?

Zinman: It might be less exciting, but maybe more rewarding.

BD: You mentioned that you started out as a composer?

Zinman: I started out as a violinist, and I studied composition as well.

BD: Has the study of composition influenced the way you look, not only at new pieces, but also at the standard repertoire?

Zinman: Of course. You learn to compose by analyzing other music, so the analysis is a very important part of learning and understanding music. You start to understand where it’s going, and why the composer put those notes there. That’s what you try to discover, and you find more and more when you do a work. That is when you discover more and more what’s behind it.

BD: Are there any pieces where you have discovered everything, and there’s nothing more to learn?

Zinman: No. There’s always something more, even things the composer didn’t know about. [Laughs] But there’s always something more, and the better the music, the more there is undiscovered about it.

Zinman: No. There’s always something more, even things the composer didn’t know about. [Laughs] But there’s always something more, and the better the music, the more there is undiscovered about it.

BD: Is that what makes greater pieces of music

— more depth?Zinman: I think so. There are certainly pieces that you feel you’ll never be able to do as great as what the music actually is, and that’s what keeps you going after it. I always have that feeling after finishing any Beethoven or Brahms symphony, and that the next time on I’ll get it better.

BD: Yet you’ve committed some of those performances to flat plastic, and they’re there forever.

Zinman: They’re there, but that’s a certain point of view that happened. Life goes on, and maybe someday my ideas will improve. I do Beethoven’s metronome marks in the symphonies, and maybe someday I’ll do them four times as slow. I don’t know. At this point, no, but it’s interesting. Music is very interesting, and the interpretation of music is very interesting, and what’s nice is I’m at the age where I can pass some of what I learned onto younger people, and that’s very rewarding as well.

BD: What advice do you have for composers, and conductors?

Zinman: Conducting is a little bit like learning to juggle, and you have to have that talent before you can conduct. You don’t necessarily have to be a great musician to be a very good conductor, but the combination of a very good musician and very good conductor is, of course, wonderful. I would advise composers and conductors to be the best musicians they can be, and that’s the most important thing.

BD: When a composer brings you a new piece and you’re working with it, is there much of a collaboration between the two of you?

Zinman: It depends on the composer. Some composers don’t like to discuss their works with anybody else, and they don’t want to discover what’s behind it. Others are very interested in what you have to say about it, and they take suggestions. So, it just really depends on the composer. Each one is an individual, and each of them has brought something into the world that they’re very worried about. So, it’s very hard for them to actually hear a first reading. Some people are very hands-on, and they want to influence everything in the interpretation. Others just sit back and let it happen.

BD: At the first reading, are the composers generally pleased, or generally horrified?

Zinman: Sometimes both. [Both laugh] They have to learn to listen to their music again and again. That’s the important thing about new music

— that it’s played again and again. That’s why recordings are so important.

BD: What about advice to audiences?

Zinman: Audiences have to listen. They cannot expect to understand anything the first time. They might get the gist of it, but repeated hearing is what makes understanding of music

— essentially getting used to the idea of the composer’s style, and getting used to everything else. If you’re only listening to stuff that you know very well, it makes listening to something new very much harder. If you can get a recording of a piece of modern music and listen to it again and again, you begin to see more and more in it, and then you’ll enjoy it much more when you hear it. That’s why radio broadcasts are very important, and why recordings are very important. People get a chance to hear pieces of music over and over again. A long time ago, when there weren’t recordings, people played them in their own homes over and over and over again.

BD: That’s why there are piano reductions of many of the major symphonies.

Zinman: Yes, of course, absolutely.

BD: You were expected to play music as a participatory sport.

Zinman: Right, exactly.

BD: Are we getting away from the participation?

Zinman: Yes, absolutely!

BD: Shouldn’t it be participatory even in the concert hall?

Zinman: Hmmm... I don’t know. That opens up a big can of worms. Audiences can prepare themselves to go to a concert by listening to the music beforehand, and finding out something about the composer. Luckily, they have very nice notes here for the Chicago Symphony, so you can read a little bit before the concerts. It would be nice to read them the week before you’re going to a concert, and read a little about the artists, and so on. Someday, I’m sure we will have at the back of our seats a video screen where you’ll be able to get your program notes visually. They’ll be a presentation by the conductor, or somebody else about the program, and you’ll actually be able to switch to see the front of the orchestra, or any place of the orchestra you want to see. That’ll make it much more participatory.

BD: That sounds like in-flight entertainment.

Zinman: Exactly! Soon that will happen.

BD: Let me ask the real easy question. What’s the purpose of music?

Zinman: [Matter-of-factly] To give meaning to our lives.

Zinman: [Matter-of-factly] To give meaning to our lives.

BD: Just like that?

Zinman: Just like that. This is not my idea, actually. A friend of mine, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, went on a sabbatical to the Kalahari. [The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for 350,000 square miles, covering much of Botswana, parts of Namibia and regions of South Africa. The name ‘Kalahari_’ is derived from the Tswana word ‘_K gala_’, meaning_ ‘the great thirst_’, or_ ‘_Kgalagadi_’ meaning_‘_a waterless place_’. The Kalahari has vast areas covered by red sand without any permanent surface water._]

He was studying the music of the various tribes, and in the end he asked them why they dance and sing. They said, “It gives meaning to our lives,” and I think that’s what music does. It gives meaning to our lives.

BD: Does it give deeper and deeper meaning all the time, or is it the same meaning each time?

Zinman: It’s hard to say. If you watch a film without music and then watch it with music, it has a deeper meaning, even though the thoughts that are expressed sometimes in music have nothing to do with this Earth. If you listen to the late quartets of Beethoven, that’s a world that only exists in that music, so we’re lucky. Also, it’s a way of time travel for us. We can go back to how people felt at a certain time. We run around and do this and that. We eat, we drink, we live, and we die, but without literature and art and music, our lives wouldn’t have as much meaning.

BD: You conduct a certain kind of music, namely Classical Music. Is this kind of music for everyone?

Zinman: No.

BD: Should it be?

Zinman: I don’t know. I don’t think so. I was hooked by it as a child, so I enjoy it. Other people aren’t hooked, and don’t like classical music at all.

BD: Are you trying to hook them, or are you just preaching to the converted?

Zinman: I would like to hook them, but essentially I’m working for the converted.

BD: Do we have enough of the converted?

Zinman: Less and less.

BD: How do we get more and more?

Zinman: [Groans] That has to do with education, and what’s going on in the schools. If teachers made it part of their classroom life, that would help. When you’re discussing Shakespeare, you also discuss the music, and if you’re discussing mathematics, you’re also discussing music. That way, music is part of a well-rounded person’s life... which it used to be, and still is, in a certain way, in some European systems of education. But we’re living in the computer age, and maybe it’ll come back that way where you’ll be able to access everything. If you study Nietzsche, certainly you’ll study Zarathustra, and certainly you might listen to...

BD: ...the work by Richard Strauss.

Zinman: Not only that, but Mozart!

BD: That’s right. Didn

’t he call Mozart, “The last chord of a centuries-old great European taste”?

Zinman: Yes, yes.

[_At this point we took care of a few technical details, and I asked him for his birthdate, which he said was July 9, 1936._]

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you want be at this age?

Zinman: Certainly, yes. I want to do less!

BD: [Surprised] You’re working too hard??? Or, you’re working too much???

Zinman: I’m working. I’ve done a lot, and there are other things I want to do besides conduct orchestras, and I’m busy with that in my spare time. But I don’t have a lot of spare time, so my idea is to have more spare time.

BD: [_Trying to be helpful_] Can’t you tell your agent to reduce the number of your engagements?

Zinman: Yes, I do, but there are certain things you don’t want to turn down. At least I don’t have two full-time orchestras now. I just have one, and the guest conducting I can limit even more than I’m doing. It’s hard to limit it when you make contracts three or four years in advance, but next season will be less conducting than this season. I have my commitments in Zurich, and I have my commitment with the Aspen Music Festival, which has great interest for me. It’s fun because I’m working with young people, and the rest of the time is spent guest conducting. But now I’m trying to get more and more months off. I have to have time to think. I’m writing a book, and I want time to play golf, and walk on the beach, and do things like that.

BD: I wish you lots of continued success, and lots more time to do the things you want to do.

Zinman: Good! It was nice talking to you.

BD: Thank you so much. I appreciate it.

© 2000 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in his dressing room, backstage ar Orchestra Hall, Chicago on February 11, 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year; on WNUR in 2010, 2012, and 2017; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2011. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.