Bernard Rands Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

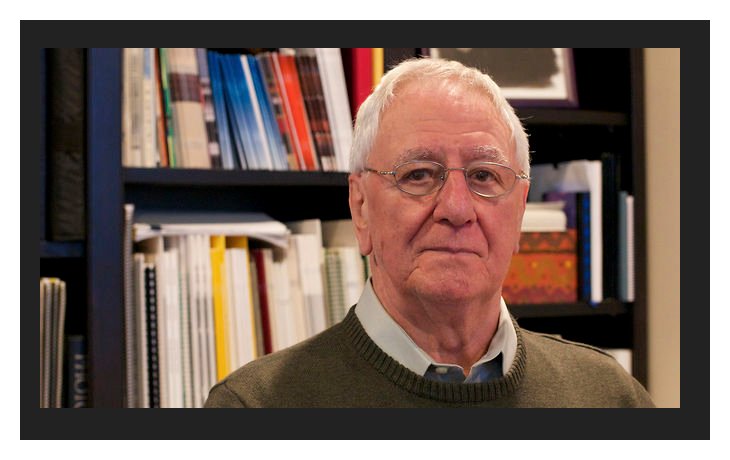

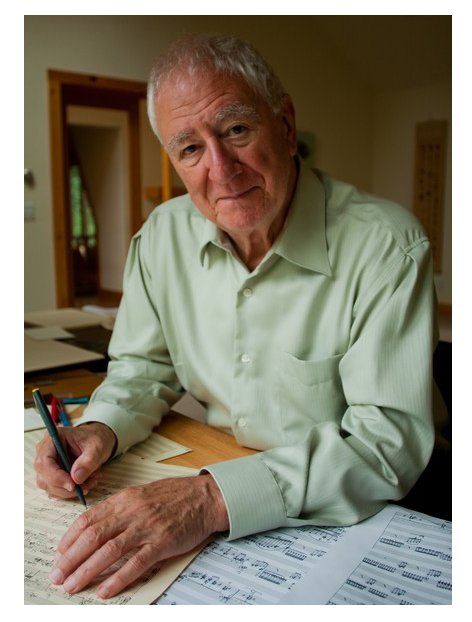

Composer Bernard Rands

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

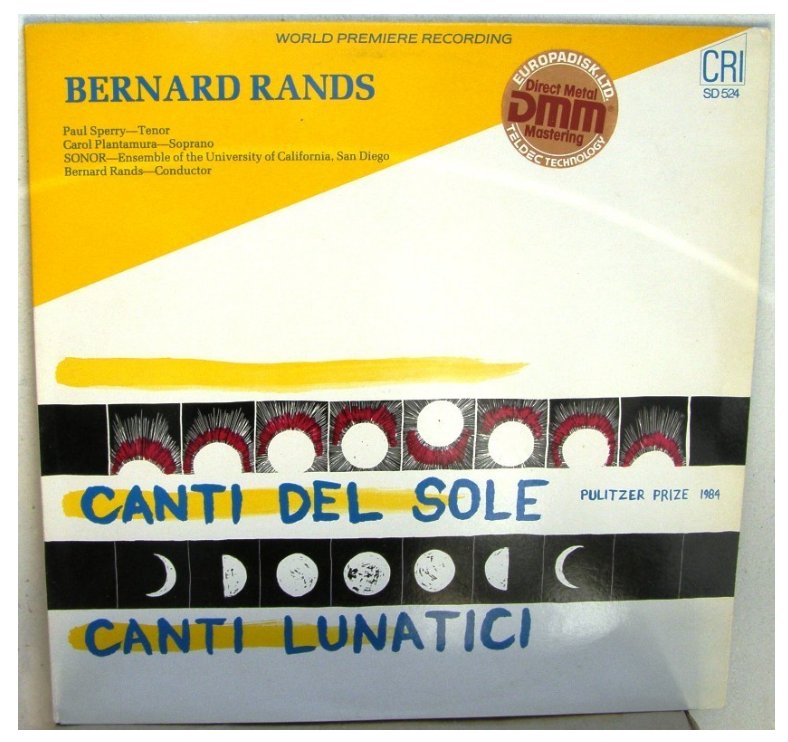

Through more than a hundred published works and many recordings, Bernard Rands is established as a major figure in contemporary music. His work Canti del Sole, premièred by Paul Sperry, Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize in Music. His large orchestral suites Le Tambourin won the 1986 Kennedy Center Friedheim Award. Conductors including Barenboim, Boulez, Berio, Maderna, Marriner, Mehta, Muti, Ozawa, Rilling, Salonen, Sawallisch, Schiff, Schuller, Schwarz, Silverstein, Sinopoli, Slatkin, von Dohnanyi, and Zinman, among others, have programmed his music. [Note: Names which are links refer to interviews by Bruce Duffie elsewhere on this website.]

The originality and distinctive character of his music have been variously described as ‘plangent lyricism’ with a ‘dramatic intensity’ and a ‘musicality and clarity of idea allied to a sophisticated and elegant technical mastery’ - qualities developed from his studies with Dallapiccola and Berio.

Rands served as Composer-in-Residence with the Philadelphia Orchestra for seven years, from 1989 to 1995 as part of the Meet The Composer Residency Program for the first three years, with 4 years continued funding by the Philadelphia Orchestra. Rands’ works are widely performed and frequently commercially recorded. His work, Canti d’Amor, recorded by Chanticleer, won a Grammy Award in 2000.

Born in England, Rands emigrated to the United States in 1975 becoming an American citizen in 1983. He has been honored by the American Academy and Institute of the Arts and Letters; Broadcast Music, Inc.; the Guggenheim Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; Meet the Composer; the Barlow, Fromm and Koussevitsky Foundations, among many others. In 2004, Rands was inducted to the American Academy of Arts & Letters.

Recent commissions have come from the Suntory concert hall in Tokyo; the New York Philharmonic; Carnegie Hall; the Boston Symphony Orchestra; the Cincinnati Symphony; the Los Angeles Philharmonic; the Philadelphia Orchestra; the B. B. C. Symphony Orchestra; the National Symphony Orchestra; the Internationale Bach Akademie; the Eastman Wind Ensemble and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Many chamber works have resulted from commissions from major ensembles and festivals from around the world. His chamber opera, Belladonna, was commissioned by the Aspen Festival for its fiftieth anniversary in 1999.

A dedicated and passionate teacher, Rands has been guest composer at many international festivals and Composer-in-Residence at the Aspen and Tanglewood festivals and was Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music at Harvard University.

Recent works include "chains like the sea" commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and dedicated to Maestro Lorin Maazel, which was premiered in the Fall of 2008; Adieu, premiered by the Seattle Symphony in December, 2010 in honor of Gerard Schwarz's farewell season; and Three Pieces for Piano, which was premiered in December, 2010 by renowned pianist Jonathan Biss who took the piece on a subsequent tour through Europe and the US including the work's Carnegie Hall debut in January, 2011. His opera Vincent debuted to critical acclaim at Indiana University Opera Theatre in April of 2011, conducted by Arthur Fagen and directed by Vincent Liotta. Rands' latest orchestral work Danza Petrificada premiered with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in May of 2011, led by the composer's longtime friend and collaborator Maestro Riccardo Muti.

In December of 1993, Bernard Rands was in Chicago for performances of his music by the Chicago Symphony conducted by Pierre Boulez. He would subsequently be comissioned by the CSO for other works which would be premiered under Boulez, Daniel Barenboim and Riccardo Muti. [See next box below.]

It was during that first visit that we arranged to meet at his apartment for an interview. While we were getting set up to record our conversation, I mentioned that he was approaching his sixtieth birthday, so that is where we began . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Are you at the point in your career that you want to be at this time?

Bernard Rands: I’ve never put the two together. It’s a fact that I will be sixty next year, but I’m also very happy with my position in the profession. I don’t think about that very much, but inasmuch as I do at all, I’ve been able to accomplish a great deal of work that I wanted to accomplish

— and not without some success, meaning that my work has access to those media for performance that I would hope they would have. So in general, yes, I’m very happy.

BD: Is it important to you that your works be performed by major orchestras as well as lesser orchestras?

BR: I love orchestras of all kinds. Obviously there’s a great excitement involved with working with the top professional orchestras. It’s a challenge in every way. It’s a challenge when one’s composing and it’s a challenge during the preparation and the rehearsals. The end result is usually a very, very satisfactory one. There’s a different ambiance about what you call lesser orchestras. I think it’s wonderful to work with musicians wherever they’re collected together according to their abilities. Individually one gets a result that is in a different way satisfying for them and for the audiences and for me. No, I don’t feel that everything I have to do is geared to the top five, so to speak, but it’s great fun working with them, of course.

BD: Without mentioning names, when you get to that top level is there any real appreciable difference between one orchestra and another?

BR: If there are appreciable differences at all, they’re to do not with quality but with aspects of sound

— their particular way of collectively playing and thinking. That becomes fascinating because there are differences. I would hate that all the major orchestras would sound just alike. Of course it depends, too, who’s on the podium at the time, but that aspect of it is fascinating. Sometimes there are little shadings, but they are noticeable, at least to those of us who work with them on a regular basis.

BD: So then a great orchestra would sound different for each conductor?

BR: Yes, it can.

BD: Will your piece sound appreciably different if it’s interpreted by one conductor or another conductor?

BR: Yes. As you know, the recording that’s just out of Le Tambourin, the work we’re doing this week here in Chicago with Pierre Boulez, sounds very different. Riccardo Muti is the conductor on the record with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The orchestra sounds different from Chicago, and Maestro Muti’s approach to the whole work is different from Maestro Boulez. Yes, it’s the same piece of music that I wrote, and I’m happy to hear the two interpretations.

Bernard Rands in Chicago

The following works have been programmed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra over the years . . .

1. Le Tambourin - Suites 1 & 2 conducted by Pierre Boulez (1993 - at the time of this interview)

2. Prelude & Sans voix parmi les voix - (CSO commission) to celebrate the 70th birthday of Pierre Boulez

3. Apokryphos for Soprano solo, Chorus and Orchestra (CSO commission) conducted by Daniel Barenboim (2003)

4. 'Cello Concerto # 1 - Johannes Moser ('Cello) conducted by Pierre Boulez (2005)

5. Danza Petrificada (CSO commission) conducted by Riccardo Muti and featured on the orchestra's European tour in Paris, Luxembourg, Lucerne, Salzburg and Vienna (2011)

6. "...where the murmurs die..." (New York Phil. commission) conducted by Christoph Eschenbach(scheduled for December, 2013)

The following are some of the other works performed at various times in and around Chicago . . .

Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - ICE Ensemble conducted by Cliff Colnot

Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - Univ. of Chicago New Music Ensemble conducted by Cliff Colnot

Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble - Dal Niente Ensemble conducted by Michael Lewansky

Concertino for Oboe and Ensemble- CSO Music Now conducted by Cliff Colnot

"Now Again" - fragments from Sappho- Contempo conducted by Cliff Colnot

"Now Again" - fragments from Sappho- De Paul New Music Ensemble conducted by Michael Lewansky

String Quartet # 2 - Chicago Chamber Musicians

String Quartet # 2 - Fifth House Ensemble

Preludes for Piano

Memo 4 for Solo Flute - several performances by Molly Barth

Tre Canzoni Senza Parole- De Paul Orchestra conducted by Michael Lewansky

Tableau - Eighth Blackbird Ensemble

"...in the receding mist..." - ICE Ensemble conducted by Cliff Colnot

Canti Lunatici for Soprano & Ensemble - Chicago Chamber Musicians

BD: When you’re writing the piece, do you build in a little area for interpretation, a little leeway, a little expansion like the expansion gaps you would find on a road?

BR: Not really. I think one tries to be as accurate and precise as one can possibly be. We work in a very precise profession, and there’s little room for error or latitude of any kind. However, the whole history of our music

— of notated music, anyway — assumes that what is on the printed page is only part of the story, and that when it comes alive through whatever medium, it will reflect whoever is involved in making it come alive. That’s part of the richness of the phenomenon of music itself, and it’s part of the joy of being a musician... to sit down and play a Schubert sonata one way, and then to hear someone else play it another way. It’s fascinating.

BD: You used the word

“precise.” Is it even possible for a work to ever be performed precisely?

BR: Oh, I think so, if by

“precise” we mean that the composer’s job is to accurately chart what his or her musical intentions are. We have a very sophisticated notation system for that which is a couple of centuries old or more, and has been extended through experiment in the twentieth century. So we have that. Once that is on the page, then it doesn’t allow a great deal of latitude. One expects, whether it’s a soloist or a large orchestra, to respect the printed page. However, there are shadings that come along with that — what is a mezzo piano to this particular conductor as opposed to another one; how pianississimo is it, at this point; all of those dynamic shadings and tempi. So even it’s marked with a metronome number, how many people can actually strike that number and maintain it during a five-minute period? There are all those fluctuations that go into making a difference and an excitement for each new performance.

BD: Would you rather the metronome marking be so precise, or would you rather just mark it allegro?

BR: I prefer that it be precise, which then says what kind of allegro it can beat. There’s a wide degree of latitude in all of those traditional markings. That’s why we have Toscanini at this speed and Klemperer at that speed with the same symphony.

BD: Yet if you have marked it with a metronome number, you expect it to be the same.

BR: Yes, but I think an intelligent conductor knows that’s simply narrowing down the opportunity, and that to disregard it is, in a sense, to disrespect the music. I’m not expecting that if I mark 72, that it begins exactly at 72. But it’s an indication that that’s the optimum to achieve what it is I intend.

BD: You want it between 68 and 74, but not down around 45 or up to 110?

BR: That’s right. However, let me tell you an experience I had. One of my favorite people in my whole life — unfortunately we lost him too early — was Bruno Maderna, the wonderful Italian musician/conductor. In the months before he died, he did a Mahler Ninth at the Royal Albert Hall in London that was slower than anything I’ve ever heard in my life!

BD: Slower???

BR: Slower and slower and slower. I think he was saying, “Look, we know how it’s usually done and we know what Mahler asked us to do. But listen, and isn’t it wonderful?” It was like he had a vision of something quite different.

BD: Did it hang together?

BR: Oh, absolutely! Absolutely!

BD: Is this, then, really your end requirement, that it hang together?

BR: Exactly. The calculations that one makes and the indications one gives as a composer are those which one believes are the best to make it hang together. However, this degree of latitude that we’re talking about is crucial to music to make it come alive and to have it have a different feeling each time it comes onto a program.

BD: You’re the composer-in-residence in Philadelphia, so you write something for the Philadelphia Orchestra. Would it be different if you were writing for the Chicago Symphony or for the Vienna Philharmonic?

BR: Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that one gets to know, on a very close and friendly basis, all members of the orchestra. One gets to admire and love certain sounds and certain combinations that one hears in other repertoire. And knowing them, one knows that when one gives them an assignment in one’s own music, it will sound exactly as one expects.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean to say you’re never surprised?

BR: [Smiles] Well, no, I’m not very surprised, ever, in terms of going in with a new work. However, , when I go to a new orchestra and have not worked with them before,

I’m always interested to see how a particular soloist or a particular section leader responds to what I’ve written, because there again, there will be that degree of latitude, and that approach that’s not entirely codified in the notation. It’s wonderful to be close to the players and to know what you’re going to get and what’s available, and who you can push to a certain limit that will produce something else that one wants. I’ve lived with orchestras virtually since I was a child and have had that experience. But in general I think knowing about orchestras is probably more important in the end.

BD: Are you currently teaching?

BR: Yes, I am. I have a professorship at Harvard. It doesn’t take much of my time, but what time it does take I give willingly because it’s part of my musicianship to teach.

BD: Are you basically pleased with what you see coming off the pages of your students, both now and in previous years?

BR: I have, over the years, had some very good students, quite a number of whom have made and are making their way professionally. They’re producing work of substance and quality, and are getting recognition for it. So your question has to be answered in a very specific way. If I generalize, then I would probably have a more negative answer in the sense that many young people now are in music studies of one kind or another in universities and institutions of all kinds. That is entirely valuable as a civilizing influence, as an intellectual discipline, as a discovery for themselves and of themselves, and hopefully bringing them to an appreciation of an art form that is so fantastic and so wonderful and rewarding. However, it’s also very demanding, as we’ve already said, about rigor and preciseness, and I don’t very often see the kind of talent that I know immediately can sustain itself. So there is an educational side which has its value, and there is an enthusiasm and an ambition

BR: I have, over the years, had some very good students, quite a number of whom have made and are making their way professionally. They’re producing work of substance and quality, and are getting recognition for it. So your question has to be answered in a very specific way. If I generalize, then I would probably have a more negative answer in the sense that many young people now are in music studies of one kind or another in universities and institutions of all kinds. That is entirely valuable as a civilizing influence, as an intellectual discipline, as a discovery for themselves and of themselves, and hopefully bringing them to an appreciation of an art form that is so fantastic and so wonderful and rewarding. However, it’s also very demanding, as we’ve already said, about rigor and preciseness, and I don’t very often see the kind of talent that I know immediately can sustain itself. So there is an educational side which has its value, and there is an enthusiasm and an ambition

— not a vaulting ambition, but a perfectly reasonable ambition that cannot be realized— and that’s frustrating because one can see that it’s not going to happen.

BD: Are we turning out too many composers?

BR: No, I don’t think that should even be a concern. I think we should educate all our musicians to the best of their ability and to the best of our ability to teach them, and let the chips fall where they may, so to speak. There are quite a few famous instances in history where one talented person has gone to a major figure and been told, “There’s no way you’re going to make it.” The thing is, if everyone is told that, won’t you go out and disprove it, and prove the masters are wrong? That’s the way it will happen.

BD: The quantity, obviously, is increasing. Is the quality of the new composers increasing, or is that something that even can be measured?

BR: It’s hard to say whether it can be measured. The quantity, on the one hand, is not any larger in proportion to opportunity in the performing media than it was in the Baroque period or even earlier. Enormous amounts of music were written at those times, and a lot of it was fourth-rate and fifth-rate! Some of the third-rate still exists, and we hear it on radio stations that play 24-hour classical music. [Both laugh] The sad thing is in that instance that very often those things are played when second- and first-rate twentieth century music is available.

BD: Should we only listen to music from the top line and maybe the next line?

BR: No. Musical culture consists of all of these things. There are moments. There are peaks of incredible achievement, and there are others that are not without their value and their quality. But today there is a very active creative level in music. Only time will tell, and what survives, survives. Again, we know historically that some of the best things often get lost until someone else finds them.

BD: Can we assume, though, that there is nothing that is great which is irretrievably lost?

BR: I wouldn’t have thought so anymore. Bach came perilously close to it, but now, with the kind of archival preservation that goes on, it would be very difficult for things to be lost.

BD: We’re talking a little bit about this, so what kinds of threads contribute to the idea of greatness in a piece of music?

BR: [Pause] To think about a piece in the abstract is already a problem for me. But if one were to try to describe some of the qualities, obviously I would think immediately that its structural concerns would be elegant and completely intact, and of a strength that sustains the nature of the musical thought. The musical thought itself is inextricably bound with all of those things because that is what the form consists of — its content and its ideas. One can only look at what the repertoire is and why it’s bequeathed to us, and why it’s sustained itself

— although goodness knows it’s under assault these days in our own culture. The number of people who are interested to listen to a Brahms symphony or at least come to a live concert to listen to it is rapidly decreasing.

BD: Perhaps the numbers are decreasing, but is the proportion, the percentage, decreasing also?

BR: I don’t know. I’m basically an optimistic person. There are times, however, in our profession at the moment that I feel the outside pressures of popular culture and more banal levels of enjoyment seem to be taking over and predominating. I’m hopeful that concert music survive, but we must be very guarded about it. We can’t just take for granted that because we think Beethoven’s nine symphonies are most supreme in their attainment, that they will last.

BD: But would we listen to, say, Two, Four and Eight if they didn’t have the label of Beethoven on them?

BR: I think so.

BD: ObviouslyThree, Five, Six and Nine would have an audience...

BR: No, the Seventh is the greatest of all! [Both laugh] You see, there again that’s a matter of opinion. If I were to be — and have — demonstrating the qualities that are archetypically and essentially Beethovenian, I would probably turn to the Seventh Symphony. On the other hand, one only has to turn to the first quarter of the First to see what’s in store. Therefore it becomes more marketplace concerns about whether this is the ongoing development of in incredible musical mind.

BD: The genius of staring with a leading chord rather than a dominant or tonic chord?

BR: Right.

BD: When you’re composing and you’re putting the notes down on paper, do you ever feel that you’re competing against the shades of Beethoven and Brahms and all of the rest?

BR: No. I don’t think any artist can carry the past on his shoulders to that extent. I think the real challenge is to be able to stand on the shoulders of one’s predecessors and have the courage to jump. That jump may be a fatal one, and that’s what makes it both exciting and nerve-wracking, but one cannot be but sustained by history. It’s nothing to do whether ultimately posterity will judge us to be equal or superior or inferior. It’s not to do with that at all. It’s a case of understanding that what our predecessors were doing was to find in themselves, and discover in themselves, the capacities that were manifest through their work. And that’s the same task today; it hasn’t changed.

BD: So you feel you’re part of a lineage?

BR: Absolutely! I will not and cannot work out of context. I’m very, very aware of all the music that pre-dates mine. I’m grateful for it. Otherwise, I’d be working in a vacuum.

BD: Are you at all aware of the music that will follow yours?

BR: No, and I can’t be because it can’t be my concern. In my own work I know what in the short-term will follow what I’ve just finished, or what I’m not working on because I already have my mind turned to it in many ways. But if you mean a long-term projection

— what will it be like in 2020 — no. I can speculate and I can make some reasonable, intelligent deductions of what it might be, but that’s not my concern. I’m not a crystal ball.

BD: This is one of my favorite questions, but we’ve approached it from a little different angle this time. Where is music going these days?

BR: Well, [sighs] I’m not too happy getting into that kind of speculation, but let me say what I think is happening now, which may be some degree of an indicator as to what will follow, at least in the short-term.

BD: That’s the usual route we take into the subject.

BR: Exactly. This century has been very rich in many, many ways, and despite a lot of the agony that audiences still find, with the large quantity of the work, I find the music of the century extraordinarily rich. It’s extraordinarily diverse. There have been some radical, fundamental changes in the shift of the nature of music itself thanks to Schoenberg and to Webern and others who followed and tried to pursue to the logical ends and conclusions the premises that they proposed for us. Pierre Boulez is a case in point. He has rigorously and strictly and honestly pursued that in a very pure manner for now fifty years and more. Because of that, our thinking about music today is much enriched by his unwillingness to bend to any other influences and any other seductions. However, no one person can cope with the whole phenomenon of music. So my view is that somewhere at every moment someone else is uncovering a little bit of what music is, and if we’re sensitive and alert enough, we’ll benefit by their discoveries. What has tended to happen, after the onslaught of radicalism in the first part of the century, is that some of the things that we thought we could dispense with — tonality, key systems, certain intervals and so on — we’re finding more and more that possibly that was a little rash to throw octaves out of the window, and to do this or that or the other. Now we can never go backwards; I’m not saying that. But what we are beginning to do again is to reclaim some of the things that we thought were not any longer relevant, and to integrate them in a way that is not backward-looking but is forward-looking. Therefore we’re building again on the shoulders of Schoenberg and Webern, and we’re adding things which their historical position forced them into rejecting. Were they alive today, I think they would probably have a slightly different view about it. There are others today who have a radical view, who in turn will find others who will take us into different paths. So there is a return to some of the aspects of melody and harmonic function and harmonic continuity and rhythmic development, an energy that possibly was, if not eliminated, was reduced to minimum concern at some points. Then, of course, the pendulum swings to the other end. We have a minimalism about tonality — a three-chord trick — which will get you to a major opera house. In the end, as far as I’m concerned, that just shows the shallowness of those concerned with that. It bastardizes a great tradition because tonality is not a simple phenomenon. It’s certainly not a three-chord trick. It’s such a complex phenomenon that it was able to give rise to all of the literature that we have.

BD: So you think that eventually, minimalism will be something to look back on and say it was a diversion?

BR: Again, I don’t want to pronounce judgment. All I can say is thus far, what I’ve heard has disappointed me. I’m always anxious and alert to new things that other people are doing. I just said a moment or two ago that they are uncovering certain aspects that I can’t deal with. But when I hear it, I think,

“That was well uncovered a long time ago, and much better.” So until I hear something that really grips my imagination and challenges my understanding, then I have to wait. But back to your question of where it is going. Once there was a grand unity of style, and one could fairly reasonably predict that all of the major changes would be within that — Beethoven coming out of Haydn, Brahms coming out of Beethoven, then Wagner and Mahler. But now the diversity is such — and it’s a rich diversity — that we can never again predict where anything is going because there are too many channels. What we do not know is whether some of them will converge or whether they will all converge. In a sense, there’s the largest mainstream that there’s ever been. There are people still out on the fringe, and there always will be and always have to be, because they’re experimentalists.

BD: But there’s a mainstream of diversity?

BR: Yes, exactly. That’s right.

BD: Is this mainstream of diversity

— the music that you write and all of the others are writing now that gain enough recognition to be considered — is this music for everyone?

BR: It has no labels of exclusion, but music of any kind is only for those people who want to access it. It doesn’t matter whether it’s my kind of music

— what we call art music, classical music — or whether it’s jazz or rap or pop.

BD: I like that. It’s very computer-ese

— “people who want to access it.” [Laughs]

BR: Well, you have to. Through modern technology, we’re blasted out of our senses by it all the time, unfortunately. But in general, one has to make an effort to go toward it, to listen to it. To hear it is not difficult now because we hear it all the time. There’s a difference between hearing and listening. If we’re talking about listening, one has to make an active effort to go to be where it is, either live or to make an effort to sit and listen to it when it’s reproduced through extra-acoustic means. It’s for anybody who wants to sit down and listen. What is so sad about so much of the twentieth century music, and the still-uneasy attitude of listeners in general, is that somehow it has a label on it that says

“it’s not for me.” No music is for me, whoever me is, until me makes an effort to find the Mozart and all of the other things that we say we love and we enjoy. The greatest pleasure comes when one is totally engaged with that music, and that doesn’t happen unless you make an enormous effort. Similarly, music now is not conventional in the nineteenth- and eighteenth-century senses. It’s got different messages and different conventions of its own now, and is also accessible once the listener has an open mind and open ears and an open heart, and says, “I’m going on this magical mystery tour. I’m going on this trip, and I’m going to listen very, very carefully.” They also need to understand that they might get lost, and that’s all right. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s not a sin.

BD: In the time that you have been observing and creating music, do you find that the hearts of the public have been opening more, or have they been closing more?

BR: I think they’re opening. There are certain people with whom one cannot bargain. It’s not the artist’s job to bargain with anybody... except possibly the agents who take most of our income! [Both laugh] No. I think a lot of people now are beginning to realize that we’re only seven or eight years from the end of a century. [Note: Remember, this interview was held at the end of 1993.] So they’ve either got to say, “This century’s been totally dead. Nothing has happened,”

— which is a preposterous notion, and most reasonable people know that’s not the case— or, “I have to get my act together, my listening act, and make an effort, or it’s going to pass me by.”I think for the most part, depending on intelligent programming and opportunity and so on, a lot of people are finding what they thought was impenetrable, in fact can be engaged with, can be enjoyed, can be even disliked. But it can be entertaining in the best sense of the word — not as a low-level entertainment, but at least it keeps you gripped by it in one way or another until it’s over. Then you might say, “Whew! Glad that’s over,” but you will have given it a solid try.

BD: Do you feel that the collective attitude of the public is a little different because the year 2000 is so close, rather than if the year 2000 were twenty years hence?

BR: In as much as there’s conscious thought about that, I think people are realizing that it’s very soon, we’ll have to refer to it as,

“That music of the last century.”

BD: Is it an artificial line of demarcation?

BR: Of course it is, yes. On the other hand, historically some things have happened that were of consequence round about turns of centuries.

BD: Sure. The major revolutions in music seem to happen every three hundred years, approximately.

BR: I mentioned a moment ago about intelligent programming. Most of us, certainly of my age and my generation, our pieces were performed in new music concerts by new music groups and ensembles. Occasionally an orchestra — especially in Europe — would have the courage to do all twentieth century music programs. That’s all well and good, and thank God all of that happened. I was very much involved in directing my own ensembles and conducting such concerts with orchestras. However, we all also longed to be in more general places. I, particularly, and I think it’s true for most, want to be in programs where there’s a context. That context can be beneficial, or it can be not so, and I don’t mean by comparison of quality or anything to do with that. Let’s assume for a moment that we’re not lying with Mozart or Haydn, and that it’s nothing to do with that. But if the music which surrounds one’s own piece, which is contemporary and in a contemporary idiom with contemporary thought, is sandwiched between, or at the beginning of a program which is followed then by Mozart and Brahms, it’s nice on the one hand to feel that one’s music can be programmed in such distinguished company. But it doesn’t help the listener. If it’s at the beginning, there’s a tendency to say, “All right, now it’s over. Let’s start the concert.” That’s the attitude of many of the administrators, and unfortunately too many of the conductors who, when they’re even willing to put a first piece on, do so with not very good grace.

BD: So you would rather be the second piece, right before intermission?

BR: This is not necessarily to do with order in general, but the other music that’s on the program could be chosen so that the whole thing is a continuity. It might even be a continuity backwards, if we have to have the grand climax of the evening with the Brahms Third Symphony, and then something that came out of Brahms, like Schoenberg or another composer that’s got strong attachments to the twentieth century composer, and then someone who came out of that first generation of twentieth century composers.

BD: Like looking into the wrong end of the telescope?

BR: Yes, exactly. That way the Brahms doesn’t come as a surprise; it comes as a revelation of the roots of everything that you’ve already been listening to. We have to get around to doing this.

BD: Is it then almost impossible to turn that ‘round, and have the Mozart and then the Beethoven and then the newest?

BR: Not at all! I think it’s perfectly possible. What I was about to say a moment or two ago about attitudes to music is there’s no question that there are a lot of younger people out there who, when the opportunity comes for them to attend a symphony concert that doesn’t cost them an arm and a leg and has some major works from the twentieth century on it, usually the box office is pretty good. At least that’s my experience.

BD: Let me come to your own composing. When you’re working on a piece and you’re putting the notes down, you go back and you look at it and you tinker. How do you know when to put the pencil down and say, “It is finished and is ready to be launched”?

BR: In general terms, every composer is different in how they understand what it is that they are grappling with and coping with, and what they’re transcribing from their inner understanding to a series of notations. I have a sense of the whole piece in my mind before I begin to write it. I don’t necessarily understand all the details, but I’d say very simply I do tend to know its scope. A little piano piece of five minutes that occurs for whatever purpose or reason is obviously going to be quite clear in one’s mind that it is that proportion, whereas a large-scale work for orchestra and chorus with texts may be fifty minutes or an hour. One knows those simple dimensions immediately, but I think your question is a much more complicated one to answer, and much more complex to know about. Without getting too technical, when one understands one’s materials, knowing what their capacity is and having explored them and exploited them in the best sense, one knows when they have reached their capacities. They’ve been used and they’ve said what they have to say in that context. Usually one knows that things are now in their right place, and that has to do with reading the music over again. With every measure that’s added and every page that’s added, one goes over it and over it and over it from the beginning, performing it in one’s mind. If they’re something of a lunatic that I am, I dance it, I sing it, I conduct it, I play it at the piano. I do all kinds of things that gives me a sense of this is right, this is the judgment that I’m making because formally, in all its proportions and all its dimensions, it makes sense. It adds up because of logic, because of conviction about it. Therefore, it is a moment one knows. I remember seeing a very beautiful film about Jackson Pollock. Here’s the actual painter working on a huge canvas, maybe the size of the floor of this room, flicking paint. He is dipping in and flicking paint here and there, changing colors sometimes with sticks not with brushes, and the paint is flying all over the place. What makes him flick here now, having flicked over there? It is because this computer in his head is calculating all of the relationships and then painting. Then he’s backing down to the far corner, and he eventually steps out and is finished with that kind of utterly non-representational, totally abstract chance art. I say

BR: In general terms, every composer is different in how they understand what it is that they are grappling with and coping with, and what they’re transcribing from their inner understanding to a series of notations. I have a sense of the whole piece in my mind before I begin to write it. I don’t necessarily understand all the details, but I’d say very simply I do tend to know its scope. A little piano piece of five minutes that occurs for whatever purpose or reason is obviously going to be quite clear in one’s mind that it is that proportion, whereas a large-scale work for orchestra and chorus with texts may be fifty minutes or an hour. One knows those simple dimensions immediately, but I think your question is a much more complicated one to answer, and much more complex to know about. Without getting too technical, when one understands one’s materials, knowing what their capacity is and having explored them and exploited them in the best sense, one knows when they have reached their capacities. They’ve been used and they’ve said what they have to say in that context. Usually one knows that things are now in their right place, and that has to do with reading the music over again. With every measure that’s added and every page that’s added, one goes over it and over it and over it from the beginning, performing it in one’s mind. If they’re something of a lunatic that I am, I dance it, I sing it, I conduct it, I play it at the piano. I do all kinds of things that gives me a sense of this is right, this is the judgment that I’m making because formally, in all its proportions and all its dimensions, it makes sense. It adds up because of logic, because of conviction about it. Therefore, it is a moment one knows. I remember seeing a very beautiful film about Jackson Pollock. Here’s the actual painter working on a huge canvas, maybe the size of the floor of this room, flicking paint. He is dipping in and flicking paint here and there, changing colors sometimes with sticks not with brushes, and the paint is flying all over the place. What makes him flick here now, having flicked over there? It is because this computer in his head is calculating all of the relationships and then painting. Then he’s backing down to the far corner, and he eventually steps out and is finished with that kind of utterly non-representational, totally abstract chance art. I say

“chance” guardedly. There is the degree of ambiguity about the nature of it, in the sense that when he makes the gesture he doesn’t quite know where the paint’s going to go. So all of that is calculated all the time, being reviewed and reviewed and reviewed until finally it’s there. When you look at a huge Jackson Pollock on the wall at the Museum of Modern Art, you’re impressed by the power of its statement. And he knew maybe one more splash would have made something that drew attention away from everything else, or completely distorted the proportions.

BD: In other words that was his genius, that he was right in his painting?

BR: Yes, and I think artists have that, and a true artist has that. It’s not something one can learn, I don’t think. One can nurture it and nourish it by experience, but even as an early musician making tiny little pieces as a ten or eleven or twelve year old, whenever one starts to compose, if one doesn’t have some sense of that inherently at that stage, I’m not sure it can be brought into being later.

BD: You said earlier that music has to be more precise. Can I assume, then, that you are precise about where you put the notes on the page, and yet when they’re played it’s almost like Pollack’s flickings, that they may or may not land exactly where you thought?

BR: Oh, no, no. No, that’s what I meant by a precise art. Where we put a dot is where it sounds, and that’s what it will sound like.

BD: But it won’t always sound precisely the same.

BR: No, it won’t, but that’s, again, not an area over which we have any control. It may be that this orchestra tunes to A-442, or 441, and certainly there’s 439. It’s already changed, to an acute ear.

BD: But it won’t be the Baroque style of 415?

BR: No, quite.

BD: When you are writing, are you always in control of the pencil, or are there times when the pencil seems to control your hand across the page?

BR: I don’t have any of those early fantasies about it. I hear my music and I write what I hear. I work on it, of course, because what one hears first is not, every time, the right one... although a lot of the time it is because one has to remember that the creative process does not leave out the intellect, the critical faculty that questions what one has heard, which is probably quite powerful and moving and even emotionally involving. But it may also, under the scrutiny of closer thought and subsequent thought, make it seem, yes, it’s fine, it’s powerful, but it can be better. That degree of refinement, which can be technical as well as in the nature of the idea itself, is very important. But given that, no. There are times when I’m up against deadlines that I wish the pencil would take over, damn it! I’d like to just go to bed for an hour and get on with it. But it’s not going to. I’m under no illusions.

BD: We’ve been kind of orbiting around this, so let me hit you with the question straight on. What is the purpose of music?

BR: [Pause] Again, there’s no one answer to a very complex question! On the one hand, I could address the question as to what are its functions in society, once it’s in existence, and there are myriad answers. Every culture and every society on this planet has music, and puts it to use in many, many, many, many ways. It’s interesting that there is not a society that does not have music. There are societies that are missing lots of other things that we in other cultures maybe think are essential, but everybody has music. So first of all, it says something about what music is as a phenomenon, and what the human need is for it. So I don’t have to enumerate any of the functions that it fills in church and in society in general and so on. From the creative point of view, it’s a way of exploring one’s self. I write for myself, and I’ll qualify that in a moment, because in doing so — and I don’t want to sound hokey about this — I get in touch with areas of my own being which I wouldn’t otherwise know. I might have access to other aspects of myself were I to be a draftsman or an architect or a farmer, but I do what I do, and that allows me to explore these areas.

BD: You don’t feel you’re a little bit draftsman or a little bit architect or a little bit farmer in all of this?

BR: Maybe. It’s possible, but I don’t make any false claims for it. Creating music means you start with a blank page and eventually there is music on it, which is then played. Then someone comes up to you and says, “Thank you. I enjoyed it. Yes, enjoyed it. I loved what you did,” or comes up and says, “I don’t quite understand. I found it a little strange, but there’s something about it.” I put myself in touch with an area of myself that I would not otherwise be in touch with, and when I offer my music to an audience, I offer them the same opportunity to be in touch with an area of themselves that they wouldn’t otherwise be. That, for me, is the main role of music of all kinds.

BD: Now, you said you write for yourself...

BR: [Remembering] Oh yes, I said I was going to qualify it, didn’t I? Thank you for the prompting. It’s a statement that I know raises the hackles on some people, and they think,

“Well, there goes another twentieth century artist completely ignoring the public or the audience, and not caring and so on, and why should we bother?” That’s not what I mean at all; it’s not my intent. My intent is to say I will not be separated from the rest of society, and I certainly won’t be separated from the human race, the species, because I’m a composer. The assumption that somehow I’m different from anyone else is an assumption that can only be justified on the basis of difference of physique, opportunity and good fortune and all the rest of it. But I believe that everyone who is willing has the same access to my music, and to a unique experience of their own from it, as I have in offering it. Therefore, if I’m true to myself, if I’m honest and don’t cheat myself and completely and always monitor my best instincts and best intentions, then I think it’s accessible and it’s available. It’s not the music that’s trying to be exclusive or esoteric. It’s got none of those concerns at all. It’s trying hard to say, “Look, let me tell you something in as simple a way that as it’s possible to tell you this thing.” Sometimes here it is straightforward, and other times here it is but we’re going to have to think about it, to listen and give it further thought.

BD: Listen and re-listen?

BR: Yes.

BD: So you expect that your pieces will provide more depth when you hear them a third and a fifth and a twentieth time?

BR: I think if an artist were to abandon that, we would be abandoning probably the crucial and central concern of our activity. Unfortunately we live at a time, in a civilization and culture where instant is uppermost. People have an attention span, at the moment, that’s not very long, and it certainly is not all too readily willing to suspend judgment. Often we hear judgment before our understanding has even begun. So my plea is to listen. Now there are certain people, if they feel rejected for whatever reason rightly or wrongly the first time, don’t come back. One can’t legislate. There’s nothing one can do about it. But I don’t believe most people are that way. Those who are interested in the kind of music that we’re talking about, in general, will be willing. Not only are they willing, but they have to have the opportunity, which means programming, again, as we talked a moment ago, in such a way that they have the opportunity. I believe then one does begin to uncover more of what’s in a piece. Let’s not forget that

in whatever medium— but particularly music, it being such an abstract art— when we think we’ve understood all that we’ve put into it, we are in a sense deluding ourselves, because for every listener that has contact with it there will be another meaning. That meaning may sometimes even be irrelevant, but it’s not irrelevant to that listener. The thing is that if one can define the message of the music in such a way that it’s clear — at least clear enough that it should not give rise to irrelevancies on a regular basis — then one has accomplished a particular task or feat already. Then, listeners in turn should respect what is being, and not let it always provoke irrelevant responses, but try to stay with it and understand it. Then it begins to reveal things that even the composer might not have known. We don’t know everything that’s in our music. Beethoven didn’t know everything that was in his music. How could he?

BD: Would you be horrified or even feel that you had failed if a piece of yours is played and everyone in the hall reacts exactly the same way?

BR: [Laughs] It would be a very, very strange experience. I’ve never had it, thus far. It’s been close sometimes, when they’ve all reacted and thought it was weird. They were pretty irritated by it! But no, that’s not going to happen, probably.

BD: That says everybody’s missed it, then.

BR: That’s happened to many people over the years. What’s so wonderful about it is that one knows there is a labyrinth, an extremely complex labyrinth of response that’s going on, and one can never know what it is. I would urge people who are in any way nervous or tentative about approaching new things in music, first of all, not to assume that there is a way to hear it. The piece will make its premises clear if it’s a good piece, and once you try to understand those premises, stay with its following of them. But the responses are as many as there are listeners, and people should not feel inferior or inadequate if they approach a piece that they don’t understand immediately. Thank God they don’t see through it, or hear through it, the first time through. Get enough from it that it makes you curious and wanting to engage with it again. If one does do that, the odds are it will reward you a second time and a third time and more. The reason that you keep coming back to those things we now call masterpieces — I don’t like the term, but that’s what they are; they’re the very best — is because they have those qualities.

BD: Let us turn the page. Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for the human voice.

BR: Oh, the joys are almost 99.9 percent of it. The sorrows are when the person who is giving the first performance has the flu the night before. [Both laugh] It’s a precarious thing. I don’t want to call it an instrument because in a way it confuses the issue. I like to think of the voice as a voice. I love writing for the human voice. I love the singing voice and I love the speaking voice, and I love the voice that has the non-verbal communication

— all the laughs and the cries and the sighs and sniffles and the coughs — that kind of vocal behavior which carries a lot of information with it and tells us a lot about a person even before they speak, before we understand their dialect, before we understand where they’re from and even what their sentence has to say. So for me, the whole area of vocal behavior is fascinating. I love poetry, and I think that one of the noblest expressions of the human voice is the voice reading poetry and performing poetry.

BD: So there’s an innate musicality to that?

BD: So there’s an innate musicality to that?

BR: Yes. I read poetry on the page a lot, and I have since I was a child. I spend almost as much time doing that as I do composing.

BD: Because you’re a composer who is used to looking at the black dots on the page and the white spaces in between and hearing it in your inner ear, I wonder if you would read a poem and hear it differently than someone who is not used to that kind of transference. [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interview with Paul Sperry._]

BR: Might well be. I wouldn’t say we have an advantage, but we might well have a different approach to it. I tend to read out aloud quite a lot, too. It’s part of the lunacy that I referred to earlier. I have a collection of recordings of poets reading their work — not only their own, but the work of other poets

— because I love to hear how someone brings the printed page to life with the language and all that that carries.

BD: Let me ask a speculative question. Are there, perhaps, poems that are so complete that you could not add anything to them; that any music you would add would be a detraction?

BR: There are, and in my own experience there are ones that I have been drawn to for a long, long time, and have nervously put off dealing with for that very reason. They seem hermetically sealed in their perfection, or whatever quality is about them that says any music would be an intrusion. On the other hand, for one or two of those that I’ve held in that kind of reverence, I have broken the rule for myself and eventually taken up the challenge to try to deal with it on the basis that the poem has its own integrity and its own authority and its own elegance and its own life, both on the printed page and in performance reading. But if I invite it into a musical context, I’m taking the liberty. The poet is giving me the liberty, either through an agent or through the fact that he’s out of copyright

, and then the onus is on me to respect it to the best of my ability, or, because it’s a living poet that I know, that I’ve been in correspondence with, who has given me permission. I then have the right to take it wherever I want to take it and wherever it will lead me. Therefore, if I see the outcome of that process as something different from the poem, then I don’t feel that I’m violating its premises or its territory.

BD: So they should each stand alone, rather than always being one or the other?

BR: Yes, I think that’s right. But when one’s finished with a work that involves literature

— the poem in this case — the outcome is not purely poetry and it’s not purely music. It’s something else. That way the poem is then not set to music as a kind of almost demeaning or even elevating way. It is inviting all of the aspects of the poem to contribute to another, third quality, which is neither poetry nor pure music.

BD: One of your poetic settings won a special award. What has been the very real effect upon you about holding the Pulitzer Prize?

BR: [Sighs] I’m involved enough in my profession to know how a lot of my colleagues feel and behave, and how the whole profession spins its wheels, shall I put it that way? Apparently there is a specific day each year when the Pulitzer Prizes are announced, and being a journalistic sponsored prize, they’re announced only on the radio. It’s usually, I gather, around eleven to eleven-thirty on this particular day. I had no knowledge of this whatsoever. I didn’t even know I had been nominated. They found me at six o’clock in the evening, when most of the hubbub and flurry of interviews was going on, and I phoned home. I was in New York City working on another project, and I went back to where I was staying that evening

— which happened to be Paul Sperry’s apartment. He said, “Bernard, where have you been all day? All the phones have been ringing off the hook. You’d better call home immediately, because people are trying to find you all over the place.” So that’s when I found out about it. I was delighted and touched that anything that I would do would gain the acknowledgement and recognition of my peers and my colleagues in the profession, and for that I am grateful. But I don’t make anything in my music for competitions or prizes or anything else. It’s heartwarming, but next morning the page is still blank and you go back to work — probably buoyed a little for the moment. I enjoyed that and I’m not pretending otherwise. It’s lovely to have these things suddenly, surprisingly placed in one’s lap.

BD: So it’s really just a great big pat on the back?

BR: It is, and there’s nothing wrong with that if one has it in perspective. I’m usually much happier when I see one of my colleagues and friends get desserts of that kind for what they’ve done. I’m a very private person, and I don’t like the clamor for interviews — especially ones for essentially journalistic purposes

like headlines and such. It’s of no concern to me whatsoever. In terms of work, I was already busy with lots of commissions, and therefore I just got on. I don’t doubt that because the Pulitzer is touted widely as some mark of distinction, that other opportunities have accrued to me because of it, and again I’m grateful. But I would make no bones about turning down a commission, no matter how lucrative it would be, if the project didn’t attract my creative imagination. I wouldn’t touch it with a very long pole. It’s not worth it.

BD: How do you decide if you will accept or turn down commissions?

BR: One knows. One knows instinctively whether that’s what one wants to do. When one is younger, one is grateful for any bread that drops in the lap, and I understand why. One of the reasons

— and I say this in all deference to the institutions that I’ve been lucky enough to serve— is that being in university sometimes has protected me from that. For example, as a young man with two children, how could I have maintained my family in any kind of reasonable living standard, keeping them alive in those early years when few people besides your friends know you, and nobody can pay you for your music? At times like that, if you’re freelancing you have to take every damn thing that comes along. There’s something about sharpening one’s skills that way, if it’s necessary. I didn’t feel that for me it was, but being a university teacher and loving libraries and books and young people, I was able to say sometimes — not often, but when I needed to — “No, I can’t. I don’t want to do that. I can’t do that right now.” I’ve maintained that, and I think in the end it’s stood me in good stead. Now, as one gets older, the commissions are of a different nature because now people are saying to you, “Look, we will buy some of your time to make something.” A good commission says, “What would you like to do most?” It doesn’t say, “We want this, this, this, this, and this for so many minutes.” It says, “What would you like to do? And if we are a vehicle or a medium through which you can do that, then here, let us buy your time. Take a year and do this for us.” I now have enough projects for the rest of my life in my mind and in my notebooks that I want to do. Hopefully, if I’m fortunate, as commissions come then I can interest people in those projects. One should never leave out the possibility that someone would come along with something quite striking that one hadn’t quite thought of. One will know immediately then whether it’s something one wants to embark on or not.

BD: So it’s not something you even have to mull over? It just comes to you right away?

BR: Mm-hm.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with the performances you’ve heard of your works throughout the years?

BR: Oh! They range even wider than the spectrum we spoke about earlier

— the latitude for interpretation — from strictness and precision to sloppy. [Thinks for a moment] For the most part I have been very fortunate. In my younger years, when Pierre Boulez was also in his younger years, he took an interest in my work. He conducted a lot of my orchestra music and chamber music of that period, especially when he was at the BBC in London and I was living in Britain at that time. He commissioned new works. I’ve worked with a lot of the major orchestras around the world. I’ve had close friendships with Riccardo Muti in Philadelphia now and Bruno Maderna that I mentioned earlier, and many others. I’ve also had the good fortune of working with lots of very fine soloists and instrumental ensembles, so that for the most part I’ve always been able to write at the extent and outer edge of my capacity, knowing that the music was going to be in the hands and instruments of very fine performers. That’s of first condition for a new work; then the work has a life of its own. It goes to a publisher, and they distribute it and so on. One can’t follow one’s music around all the time just in order to hear it. When one’s heard it a few times, then you don’t bother with it. It goes on its own life.

BD: Would you want to follow it more than you do?

BR: No, except on special occasions. I’ve heard Le Tambourin many, many times and I’ve conducted it lots of times. But immediately when Shulamit Ran told me that Pierre Boulez was doing it, even if I’d not been giving pre-concert talks for all of this series, I would have wanted to be here anyway to see him, be with him, spend time and talk because of what I said about him earlier

BR: No, except on special occasions. I’ve heard Le Tambourin many, many times and I’ve conducted it lots of times. But immediately when Shulamit Ran told me that Pierre Boulez was doing it, even if I’d not been giving pre-concert talks for all of this series, I would have wanted to be here anyway to see him, be with him, spend time and talk because of what I said about him earlier

— that the consistency of his approach will be present, and there will be a different understanding of it from others, and that’s fascinating. But I’ve been very, very lucky. There are times, of course, when like everyone else I’ve been very dissatisfied.

BD: Do you make that dissatisfaction known?

BR: I’m not slow at letting it be known, no. [Both laugh] We’re the only guardians of our property, of our work, in that sense. One tries to do it always in the best climate one can create

— of friendship and exchange — but if someone is violating, either deliberately or simply unwittingly, what one intends, then I think one has to speak up and just make it clear that it’s not acceptable.

BD: What about the recordings? They have a little more permanence and universality. Have you been pleased with those?

BR: Yes, I have. But if you look through the Schwann Catalog, you’ll see my name maybe with two lines to it. It’s something I’ve neglected very badly. There’s no good reason why I have, nor why I should have. I’ve always been so busy with making music in one form or another I’ve paid very little attention to recording it. There’s the CRI, which I did myself. I conducted the pieces on that, and therefore I have to say at this point that I was fairly satisfied with what we did.

BD: I hope you’re still pleased?

BR: Yes, I am because it was done with the ensemble that I directed for several years. I formed and directed it, and it was an ensemble that was formed on the basis of rehearsing regularly and intensively, whether or not we had concerts. That led us to a level of performance and understanding and sensitivity to each other, musically, that was a thrill. It was a joy. So I know that they are a fairly faithful representation of what my intentions were at that time.

BD: What about the one on New World?

BR: That’s very, very good. Riccardo Muti did the two Le Tambourin Suites and Ceremonial 3. By the time we recorded them, he had done Le Tambourin seventeen times in one season.

BD: My goodness!

BR: We did it five times in Philadelphia, and then we did two children’s concerts in relation to education concerts. Then we took it on tour for eight concerts around the United States, and then we did it for Radiothon and something else. So that by the time we got to record it, the players treated it like repertoire. When they played part of it last week in Philadelphia, it was like they just put out another piece from the library and they played it quite well.

BD: I would think that would be immensely satisfying.

BR: Yes. The third piece on the new CD is conducted by Gerard Schwarz. Gerard came in at the very last moment to do the Canti Dell’Eclisse because Muti was sick. Imagine getting the score! It’s over thirty minutes long and is quite complex with a soloist involved. I got the message that Riccardo Muti could not come; his doctor had forbidden him. I think it was on the Wednesday prior to the Tuesday rehearsal of the next week. The first thing I said when the office called me was, “Oh, my God!” They said, “Will you do it?” and I said, “Yes I will, and I can, but that’s my last option. Try whoever is available, but especially try Gerard Schwarz.”

BD: You would rather have Schwarz do it rather than wait until Muti could do it a year later?

BR: Yes, because the recording had already been waiting for the dates of the performance of this. I didn’t want to wait any longer for the CD to come out, nor did the company that wanted to bring it out. Gerry was satisfied with a week to learn it. In typical fashion he took on the whole program, and I must say he did a remarkable, remarkable job. That kind of musicianship is also very, very special for someone who can do that.

BD: There’s also a recording on Neuma?

BR: Of chamber work, that’s right, with the Boston Musica Viva. I forgot about that; it just came out recently. That’s a little work for flute, harp and string trio, which is nicely done. Now, come to think of it, there is the Cleveland Chamber Symphony recording which is out on the Gunther Schuller label, GM. That’s very nicely done, too. There was also a vocal piece on a special disc that Universal Edition in Vienna brought out, but for the most part that’s it. I have to be more attentive to this, though. I’m the world’s worst promoter and businessman. I’ve been dealing with that side of my life and I am not very good at it.

BD: One last question

— is composing fun?

BR: Your question has terminology that is used on so many contexts which are not related to what I do that I have difficulty answering immediately. Does it make me happy? In the long run, yes. This is my life; this is who I am. What I do is not an occupation; it is who I am; this is me. But there are very sad times about it that have nothing to do with whether somebody likes or dislikes what I do, or rejection professionally. That’s not an issue. But there is always a feeling, even when one is satisfied with what one’s done, that there is yet more; there is another way. That’s what gives rise to the next work, because were it not so, then we would draw the last double bar line and it would be over. But that is both an anxious feeling and it’s also fun to know that there is something else.

BD: Thank you for being a composer. I appreciate your spending the time with me. This has been a wonderful conversation!

BR: Thank you. I enjoyed it, too.

======= ======= ======= ======= =======

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

======= ======= ======= ======= =======

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on December 3, 1993. Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1994 and 1999, and on WNUR in 2003. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.