Manuel Rosenthal Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . (original) (raw)

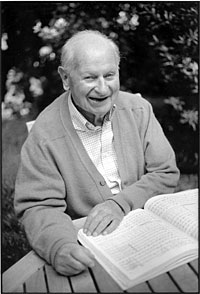

Indeed he is the Grand Old Man of French Music. Manuel Rosenthal, at age 82, is still going strong in the musical world. As composer, conductor and arranger, he has given so very much and seems to be afraid of nothing. One only need mention that he conducted his first Ring cycle this past summer to put to rest any arguments about that! Speaking about Wagner, Rosenthal did mention to me in our conversation that he would love to conduct Die Meistersinger because it's a living opéra-bouffe.

Perhaps, along with Jean Fournet, the surviving living link with Debussy and Ravel, Rosenthal stands as the guardian of the great French Lyrical Tradition. In both his compositions and his interpretations, his music, according to the "old" Grove Dictionary, "is that of a superior, refined and vigorous craftsman, typically in the French tradition."

When I caught up with Maestro Rosenthal, he was back in Seattle preparing a production of Manon. He seemed quite pleased to be able to chat about the various topics I brought up, and his English was very detailed

Bruce Duffie: Tell me a bit about Manon.

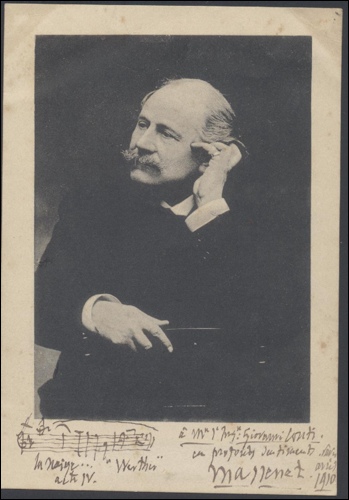

Manuel Rosenthal: It’s a story about Massenet, rather. When I was a young composer, studying with Maurice Ravel – I was his only pupil, you know – we talked about the older composers, and I asked him about studying with Gabriel Fauré. I knew he (Ravel) had a deep respect for Fauré and had dedicated hisString Quartet to him, and I wondered what Fauré gave to him. He said, “I have great admiration for this musician, but I owe everything about composition to Massenet.” I was very surprised because already in that time, Massenet was in the old period. I asked Ravel why and he said, “He taught us a lot about writing melodies and harmonies and about orchestration.” The orchestration of Massenet is very precise, clear, and interesting. When you study the full-score of Manon, you discover that it’s fantastically well written, taking care of the voices, and at the same time always bringing new colors to the orchestra.

BD: So Massenet was innovative?

BD: So Massenet was innovative?

MR: Oh yes, certainly. In harmonies, melodies and in orchestration, I would say that he was the first of his time to bring this new kind of art to the opera house. As a conductor, you have a great happiness in studying and rehearsing. If you follow very closely with great respect the indications Massenet wrote with great precision, you get a fantastic aspect of the music itself.

BD: Does this fantastic orchestration carry through to his other operas?

MR: It’s more important inManon, but it’s also apparent inCendrillon, Grisélidis, and of course in Werther. But it is more important to be observed in Manon because I think this opera is the most perfect among all the works by Massenet.

BD: Is it the most perfect French opera?

MR: That is difficult to say. Carmen is still the model not only of French opera but, in the opinion of many opera directors, the best opera ever written. It is still #1 all over the world and nothing approaches it, but Manon is very close. Besides, I have always been impressed that Ravel told me that Massenet showed not only the means of orchestrating well and constructing melodies and harmonies, but also that he and Debussy were very impressed and entranced by Massenet’s music. At that time, I was really surprised to hear such a statement, and Ravel added, “If you look closely at Debussy’s Pelleas or at my L’Enfant et let Sortileges, you will find many places not copying, but being a tribute to Massenet. One special aria in L’Enfant, which is called commonly called ‘L’air de l’Enfant,’ is written exactly like ‘Adieu petite table’ in Manon.” When I asked him why he had done this, he said it was just a tribute to Massenet. He always thought more and more that he really was going to pay tribute to Massenet because the more he composed, the more and more he felt the influence of Massenet and his music.

BD: How does Massenet stand with the other French composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

MR: It’s really a very particular point of view about Massenet. Although many people love this kind of opera, many people don’t understand completely the perfection of such an art. A couple of years ago, when the management of the Metropolitan Opera asked me to do Manon, they were almost ready to believe that I would say no. They were very surprised that I said yes immediately and asked me why. Remember, I don’t generally conduct in the repertoire. I’m known to conduct contemporary music – Berg, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, as well as Debussy and Ravel. But I told them it was because of the respect and lasting admiration of Ravel to Massenet that I got to study Manon, and I discovered what kind of perfection musically, melodically, harmonically and orchestrally was in this music. I would like to conduct Manon in such a way that it will appeal like something more important than it used to be in so many minds.

BD: There seems to be a resurgence in the popularity of several operas by Massenet. What is the reason for this?

MR: First of all, we have to go back and discover these works after having forgotten them. But Massenet was never forgotten. However, you might know that by the time we giveManon at the Met, it will have been absent for 23 years. It was played, of course, at the New York City Opera and many other places in the United States [including two seasons in Chicago, both times with Alfredo Kraus!], but they discovered that they couldn’t give it properly and they felt that I was the man to give Manonits right place!

BD: Managements seem often afraid to give French operas because of the difficulty performers have with the “French Style.” How do you bring the proper style to these works?

MR: I don’t think it’s so difficult. Take the example of the Parade program I have given there twice. That was a success – even at the box office! It was very easy to get American singers to speak in French and to adapt their voices and way of thinking and acting to the French style. My wife attended many performances of this Parade and she said she had never gotten so many of the words until those performances at the Met!

BD: Were the singers working harder at their diction because it is foreign?

MR: That’s it of course. They had to work harder and I was there to teach them. That is what I am doing now in Seattle and will do at the Met next year. It’s really rather easy and I don’t feel it’s very hard. But remember, French is a difficult language even for the French people. It’s difficult to pronounce, and in the case of Manon, difficult to get the meaning of some words which are not used any more. If we miss a few words from time to time, it won’t be capital. We will lose only a few of them, but in general, the corrections in pronunciation are only in accent and inflection. There is trouble with the open “a” and a graceful “a,” but that is also a problem among French people.

BD: Then this is a good time to ask if you believe in opera in translation.

MR: Not always. I don’t think that French operas are winning anything by being translated. It’s so difficult. The French language is a very precise language, and it is always losing something in a translation. There is some inner meaning – you call it “double entendre” – which is losing in a translation. So I think it’s better to have enough rehearsals to teach American singers to sing it in French than to sing it in English. Sometimes it’s translated very well – Debussy’s Pelleas is translated very well into English

BD: As the Music Director, how much do you get involved in what’s happening dramatically onstage?

MR: My personal habit is to be there from the beginning of the rehearsal period. I go not only to all the coaching sessions with the singers, but also to all the staging sessions. It’s not that I distrust the stage-director or the coaches, but I want to be there in order to keep bad habits from slipping in. Sometimes when they are learning different stage movements, they are losing the tempo of the music. It’s so easy to keep bad habits, and in this way I am always there. I don’t say anything to the stage-director except when he tries to do something that goes against the music. If the director attempts something that would prevent the singer from singing in the right tempo, I would tell him it’s not possible, or that it would disturb the singer to do that. So, he has to find another way.

MR: My personal habit is to be there from the beginning of the rehearsal period. I go not only to all the coaching sessions with the singers, but also to all the staging sessions. It’s not that I distrust the stage-director or the coaches, but I want to be there in order to keep bad habits from slipping in. Sometimes when they are learning different stage movements, they are losing the tempo of the music. It’s so easy to keep bad habits, and in this way I am always there. I don’t say anything to the stage-director except when he tries to do something that goes against the music. If the director attempts something that would prevent the singer from singing in the right tempo, I would tell him it’s not possible, or that it would disturb the singer to do that. So, he has to find another way.

BD: Are there cases where the director is completely wrong-headed in his concept?

MR: Oh it happens, of course. I remember seeing Bruno Walter rehearsing Magic Flute at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, and all of a sudden he stopped the rehearsal and told the electrician that he didn’t want a blue light at that point. “The blue light,” he said, “didn’t go with the music.” And from that I learned that the conductor must be the big boss. Of course he must work in close collaboration with the director and they have to both be working for the same opera, but he has the final word because he knows the music from beginning to end, so he knows better than anyone what the composer meant when he wrote this opera.

BD: How early do you become involved with a new production – the Manonin New York, for instance?

MR: Well, I’m going back to the Met this fall [1985] for performances of Parade and M. Ponnelle will be there, so we will have many working sessions together. But both of us know already what we want in broad lines. The first thing is that we don’t want the ballet. We are taking the ballet out because the ballet has been added to the story. There is no reason to have it, and the music loses the meaning and its strength and the line of the dramatic story. It’s a drama, not a comedy, and we have to feel the sprit of the French revolution. The crowd at the beginning feels the society of Paris. De Brétigny is a neuveau-riche, and made his money selling rotten goods to the army. He is a very vicious man and is using money to pervert young girls just coming from the country – like Manon. He wants to include her in his harem. Manon falls in love with Des Grieux, but she sees so many ladies who are well-dressed and wearing jewels, and she thinks, “Why not me?” De Brétigny has Guillot in his employ as a kind of a pimp, so they work together to catch Des Grieux cheating to have him put aside so they can get Manon. This is the real original story by Prévost. The story is very short, so many words have been added, but the spirit is there. I’ve worked with Ponnelle and also with Patrick Bakman, who is here in Seattle, to get Manon as a drama and not as a comedy. "The Very Sad Story of Manon and Des Grieux" – that would have been the real title.

BD: What about Massenet’s later work – Le Portrait de Manon?

MR: That’s just a little amusement on the side. It’s only because Manonbecame so popular that somebody asked him to put an aside to Manon. It’s charming, but that’s all – nothing to compare to the real opera.

BD: Have you ever conducted some of the other operas by Massenet?

MR: No. I know many of them, but I didn’t conduct them. The Met asked me to do Werther, but I refused because I don’t feel like it, and when I don’t feel like being part of the production, I refuse. I have nothing against the work, I just don’t have the mind to conduct it. Some other conductor would do it better. There is one other opera by Massenet which is a masterpiece: Le Jongleur de Notre Dame. In general, it’s not very well received because there are no women in the cast. The beautiful story takes place in a monastery in the middle ages, and it used to be a great success maybe 80 years ago at the Paris Opera when the famous baritone Fugère sang the title role. It’s a wonderful score, very different from the others in that it is very stern, very severe. I’ve tried many times to induce directors to give it, but their first objection is that it’s too short. They need another one-act opera.

BD: What would go well with it?

MR: Perhaps another Massenet opera like Grisélidis. It’s a middle-age legend and a very charming score. Jongleur first because it’s so stern, and then it would be nice to finish with Grisélidis. Massenet always tells a very interesting story, and people like stories. If they go to an opera, they like beautiful singing and playing, but they like also to be told a story. Massenet was very clever to always find a good story to make an opera.

BD: Tell me about some of your own works for the stage.

MR: An opéra-bouffe called Rayon des soieries was my first composition for the stage and was performed when I was 24 years old. It takes place at the silk counter in a department store. It’s a one-act work lasting for one hour and has some jazz music in it which many people resented at the time (1930). Then I wrote a musical comedy because the spoken text is so important, and it’s called La poule noire – the Black Hen – and was even given in New York. It’s the story of a widow who tries to be faithful to the memory of her husband, but she falls in love with a young man and is full of comic details. It’s been performed many times at the Paris Opéra-Comique. Bliss Hebert, the artistic director of Santa Fe, is interested in doing these two together as a full evening. Two very different pieces, but both comical. I hope it will come about because I know the reputation of the Santa Fe Opera is very good. I have also written a couple operas, but only one has been performed on the stage. It’s called Hop, signor!It’s a full evening, three acts, very dramatic, and I think it’s my best work. It was badly received, but one of the singers in the cast said that it would get the reception it deserves 25 or 30 years from then (1962). The other work is a one-act work by the same writer, Michel de Ghelderode, and it’s about the crucifixion of Christ. There is only one man and ten ladies, and each of the women tells her story. It’s only been performed in concert versions for the radio.

BD: You’ve conducted your works, but are you the ideal conductor of your works?

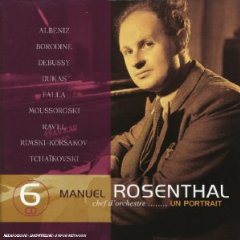

MR: No one is the ideal director or conductor or performer of these works. I am sure that I’m not the best one, but, you know, when others conduct my works it is very disturbing for me to hear it conducted in another way. All the conductors in the world that have a name have done my Gaîté Parisienneand every time, it’s another work. I listen and say here and there, “Oh, I didn’t think about that!”

MR: No one is the ideal director or conductor or performer of these works. I am sure that I’m not the best one, but, you know, when others conduct my works it is very disturbing for me to hear it conducted in another way. All the conductors in the world that have a name have done my Gaîté Parisienneand every time, it’s another work. I listen and say here and there, “Oh, I didn’t think about that!”

BD: You are both a composer and a conductor, so perhaps you’re the ideal person to ask one of my favorite questions – where is opera going today?

MR: Well, it’s coming back. The idea of writing big works for the stage is coming back for the young composers. For a long time it was despised by them, perhaps because they were not ready for it. The language of the 12-tone system is not really easy to manage with an opera.

BD: How much can a composer (or a conductor) expect of the public?

MR: It’s difficult to know because you cannot order the public to like something. It has to come little by little, and it’s only the public that is right. You cannot order them even if you give lectures and explanation. If they are not ready, they will not come. The public has a very strong way of acting. After working all day, they rush home to change clothes and eat a snack, then they buy a seat which is expensive at the opera, so they have a right to express an opinion and to say whether they like it or not. Even if you don’t agree, you have to accept it because we do music for them – not for the musicians!

BD: Do you compose for the audience?

MR: Of course – for the ideal audience. It might not be for today, but for twenty years from now and I have to accept that. It was always like that. We cannot say that they are wrong. They need time to like and to be instructed.

BD: Does opera work well in concert?

MR: Not very well; it is not the ideal. You are losing lots of meaning when you see people telling you a story while standing there in evening dress. You have only the music.

BD: Is opera art or is it entertainment?

MR: You only have to go to a record shop to see people lined up to buy opera. There is a big appeal. People are attracted because it’s interesting and it’s entertaining, too. And it’s very noble. Because so many superb musicians chose to write operas, it’s one of the best ways of doing music.

BD: Do you think opera works well on television?

MR: They are beginning to make progress and to make it interesting. What I prefer is the way Ingmar Bergman did the The Magic Flute. It was not pretentious at all. It was not instructing, but he tried to show the entertaining part of an opera. That’s a model. Very often it’s too serious – pictures of singers opening their mouths wide is not very pretty to look at. The way Bergman understood it should inspire others.

BD: Do you feel that audiences in general take opera too seriously?

MR: There are two publics. One pubic likes the voices, the bel canto, and they come to hear them and don’t look at the stage very much. The other people come to have entertainment and they are interested by the staging, by the scenery, by the costumes, and they will force those involved in producing it to make it a complete entertainment.

BD: Are you good audience?

MR: Oh yes. I love the stage. I don’t like the movies because it’s dead forever. You don’t participate in a movie. What you see is there forever, but when you go to the theater – either the dramatic or the lyric stage – you are participating. Jean Cocteau once said, “The public also has talent.” You can ask anyone onstage and they will tell you that playing the same work many times, they never play it the same way because it’s according to the public of that special night. They cannot explain that, but they feel it. When I come on the podium, I can feel on my back along my spine if the public is ready to accept what we will be doing, or if we will have to fight the public. That happens if they are cold. If you are lucky, you can still get them maybe after a half hour or an hour, but if happens and it’s wonderful.

BD: You’ve spoken of films as “frozen” performances. Are recordings the same?

MR: Yes. A recording is never really perfect – or rather it is too perfect. Nobody plays or sings like in a recording. You never hear mistakes on recordings (except for “live” recordings), but mistakes happen in performances all the time, and that’s more human. And during a performance, the performer goes with the public and the public goes with him. They are together.

MR: Yes. A recording is never really perfect – or rather it is too perfect. Nobody plays or sings like in a recording. You never hear mistakes on recordings (except for “live” recordings), but mistakes happen in performances all the time, and that’s more human. And during a performance, the performer goes with the public and the public goes with him. They are together.

BD: Are recordings, then, a fraud?

MR: It’s like fruit in a can – you take it when you cannot get fresh fruit. That is only my opinion.

BD: Are you proud of your own recordings?

MR: No. I’ve made quite a few – Debussy, Ravel, even a complete Tosca in French. I am proud of that one because it’s very musical. You can never do that onstage because of all the accidents which happen, but I never listen to my recordings because I am always full of remorse. Today, it would be much better, but what can you do – it’s made.

BD: There must be a few which you feel are good representations of your artistry.

MR: Yes. Besides theTosca, there is my Jeux, and Afternoon of a Faun, and the unabridgedDaphnis and Chloe which is now re-issued on compact disc in Paris. Also some Falla things. I have made some very good recordings but still I don’t want to listen to them. We are progressing every day. If not, why should we go on?

BD: Tell me about one last composer – Jacques Offenbach.

MR: Well, I conducted many short operas of his for the French radio before the war, and I came to Gaîté Parisienne just by hazard. A friend of mine, the conductor Roger Desormière, was a friend of Leonid Massine, and was engaged to write Gaîté Parisienne on themes by Offenbach. I don’t remember why, but he couldn’t do it and he asked me as an old friend. He said, “Only you can do that for me, if you would accept. Please do it.” I was not interested at that time; I had never orchestrated music of another composer and tried to resist. But I did it and got immediately on bad terms with Massine. He said I was being disrespectful of Offenbach because I changed some harmonies and key signatures. So I told him I didn’t want to argue about it, but we should go to someone whose opinion he cannot refute: I meant Stravinsky! So, we went to Stravinsky and a pianist played the score for him, and Stravinsky said, “Leonid, if you refuse this score, you will be refusing the biggest success of your life!” And that was it, and it became one of the biggest recording successes of the world. It was written in 1937 and is still popular today! There is even a second version of the ballet now by Béjart which is very successful.

BD: It seems that your career is a series of successes!

MR: Well, I am doing so many things that some have to be successful!

BD: Thank you so very much for spending the time with me this evening.

MR: You are very welcome.

Ravel's last pupil and France's most important conductor

Wednesday, 11 June 2003

Manuel Rosenthal was one of the last living links with the musical Paris of the 1920s and 1930s, the Paris that was the home of Igor Stravinsky, that boasted Maurice Ravel - Rosenthal's teacher and friend - and hosted Sergei Diaghilev. For almost 70 years Rosenthal was France's most important conductor, fearlessly introducing modern music to reluctant audiences. And, although his name reached a wider public largely through the Offenbach orchestrations that formed his 1938 ballet Gaîté Parisienne, he was the composer of a substantial and distinguished body of music.

Manuel Rosenthal, conductor and composer; born Paris 18 June 1904; twice married (two sons); died Paris 5 June 2003.

Rosenthal's beginnings were hardly auspicious. Born in 1904, the illegitimate son of a Russian woman and a propertied society figure, Manuel never knew his real father (though, aged 10, he once went to see where he lived, on a large estate at Saint-Cloud, west of Paris); his surname came from his stepfather. But his mother, Anna Devorsosky, was no ordinary woman: beginning in 1885, she had walked from Moscow to Vienna to escape the anti-Semitic pogroms, travelled to Palestine, where she married a pharmacist, walked back to Italy, and caught a train to Paris - she was a tough lady, and Manuel inherited something of that toughness.

His career took a number of unpredictable turns. His principal childhood interest was literature, and it was thought he might become a writer. But, like many young Jewish children, he was also taught the violin, beginning when he was six. So, when his stepfather died in 1918, on the day of the Armistice itself, and he found himself, at 14, head of the household, it was to the violin that he looked to feed his mother, sister and himself, and he earned a living playing in the theatre orchestras, café ensembles and other such groups, then commonplace all over Paris.

The violin seem to offer Rosenthal a career and so, at 16, he entered the Conservatoire as a violinist, though more out of a sense of obligation - at home he was discovering the pleasure of composing. When at the end of his first term a piece was required for a sight-reading exam, Rosenthal wrote a Sonatine for two violins and piano, and thought no more about it. Jules Boucherit, his violin teacher, was impressed and sent the score off to the Société Musicale Independante - one of the two main chamber-music societies, with a committee composed of such luminaries as Stravinsky, Ravel, Béla Bartók and Sergei Prokofiev.

A few weeks later Rosenthal received a letter telling him that his_Sonatine_ would be performed at the SMI's 100th concert and at first assumed that someone was playing a practical joke on him. The reaction to the performance of his sonatina changed his life:

Everyone whistled and shouted; it was a terrible noise. So you can imagine that I was as pleased as Punch! When you're 17 and you do something you don't think much of (it wasn't anything serious for me) and they play it in public - and the hall was stuffed full because it was the 100th concert . . . People were shouting, "He's mad!" Well, that was really amusing! I thought: it's great fun, music!

A publisher took a shine to the Sonatine, and Rosenthal sent copies of that and other pieces to anyone he thought might be interested, or useful, including Ravel - who reacted with silence. At that point he was called up for national service and spent the next two years in uniform. On leave in Paris, he was invited to dinner by the pianist Madeleine d'Aleman, who arrived an hour later, explaining that she had been out at Montfort-l'Amaury, Ravel's home, accompanying Ravel songs to their composer. When she turned down an invitation to stay for dinner, Ravel asked why and, hearing Rosenthal's name, asked d'Aleman to apologise for his lack of response and to tell Rosenthal he was going to study with him. Since Ravel had had only two students before, Maurice Delage and Jean Huré (later Rosenthal's teacher of fugue and counterpoint), Rosenthal could hardly believe his luck.

He duly became the third and last of Ravel's students and, over the remaining 11 years of Ravel's life, a close friend. Ravel's teaching methods could be severe. Rosenthal once proudly turned up with a fugue in which, he thought, he had finally found his voice. Ravel read it through silently, picked it up, ripped it into pieces and threw the fragments into the fireplace. Rosenthal watched, horrified, then grabbed his coat and stormed out into the pouring rain.

He was sitting in the train, waiting for it to return to Paris, when there came a tap on the window. Ravel, standing the downpour, asked, "So you don't say goodbye to your teacher?" - and Rosenthal understood that he had his best interests at heart.

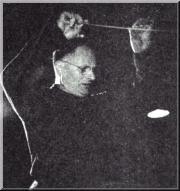

It was Ravel who was responsible, in 1928, for Rosenthal's conducting début, arranging for the Concerts Pasdeloup to put on an evening of Rosenthal's own music and insisting that the composer conduct. Rosenthal, who had never mounted the podium before, was beside himself with fear, but the results impressed Désiré-Emile Inghelbrecht and Rhené-Baton, the two most prominent French conductors of the day, who came backstage at the interval. "How long have you been conducting?" Inghelbrecht asked. "About an hour," Rosenthal answered.

Inghelbrecht thought enough of Rosenthal to appoint him his assistant when the Orchestre National de France was founded in 1934, although the relationship was fraught with tension: Rosenthal felt that he was being used as a dogsbody. But there were advantages, as when he assisted Arturo Toscanini in two concerts in 1934.

He continued to compose, largely chansons for various shows - and, to his later regret, marrying a chorus girl (a Mlle Troussier, in 1927) from one of them. Two operettas, Les Bootleggers (1932) and La Poule noire (1934-37), failed to generate much enthusiasm; a symphonic suite inspired by Joseph Delteil's Jeanne d'Arc (1934-36) showed a tougher creative character, and was followed by the oratorio St François d'Assise in 1937.

Rosenthal's breakthrough as a conductor came in 1936, when the Radio PTT - the forerunner of Radio France - set up its own orchestra and appointed him to its head. He now began a tireless crusade on behalf of contemporary music, conducting Ravel of course (though he had only a year to live) as well as Stravinsky, Bartók and other "difficult" composers - and Rosenthal's sharp tongue meant that he, too, could sometimes be difficult.

His championship of Stravinsky was soon to stand him in good stead. Roger Désormière, lacking time to undertake a commission, asked Rosenthal to take it on - the orchestration of a series of Offenbach numbers to form a ballet. Rosenthal reluctantly complied, only to find his score turned down by Leonid Miasine - Massine, the choreographer. He then suggested bringing in an arbitrator and proposed Stravinsky:

I asked him and he was good enough to say: "Since it is you who ask me, I'm happy to do it." So we go to his place with Miasine; the score is played to him - and Stravinsky takes Miasine by the collar, takes him toward the door of his flat and says: "But listen, that's marvellous - Leonid, if you turn this score down, you will probably turn down the biggest success of your career."

The subsequent worldwide success of _Gaîté Parisienne_was to assure Rosenthal a decent income for the rest of his career - though some hard years were yet to come.

Turning down an invitation from Serge Koussevitzky to join him at the Boston Symphony Orchestra, at the outbreak of the Second World War Rosenthal signed up, becoming a medical corporal, and was captured, spending nine months, in 1940-41, in captivity. On repatriation, as a Jew and now a member of the Resistance, he spent his time on the run from the police. He was composing all the while, using music to buoy up his spirits, as in the orchestral showpiece_Musique de table_:

My wife was ill in hospital, I had nothing to eat, I was all on my own, sad. And then all of a sudden the musician's imagination begins to work. I said to myself, this is the moment to act as if there were a huge meal. It was a tradition of Louis XIV, the musique pour les soupers du Roi of Delalande. So I imagined an enormous supper in the form of a concerto for orchestra. It's the most savant of my works!

With the Liberation, Rosenthal took over the conductorship of the Orchestre National, continuing his missionary work on behalf of new music. In 1947 an invitation from Jack Hilton brought him and his orchestra to join Sir Thomas Beecham and his, the Royal Philharmonic, in a concert that filled the Harringay Arena with 13,500 listeners.

In 1948 he was appointed chief conductor of the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, multiplying the number of subscribers tenfold in his first season. But his tenure lasted only until 1951, when the prudish orchestral authorities discovered that the second "Mme Rosenthal", the soprano Claudine Verneuil, was not legally his wife and terminated his contract. Not until the following year did he divorce his first wife, leaving him and Claudine free to marry at last.

He spent much of the next few years working as a guest conductor, in North and South America, mainland Europe and the Nordic countries, the Middle East. In 1962 he became professor of conducting at the Paris Conservatoire, retaining the post until 1974; and a 1964 appointment saw him chief conductor of the orchestra in Liège for three years.

Before his very last years, when his sight began to go, old age hardly seemed to touch him. In his seventies he was a frequent visitor to North America, attracting especial praise for a triple bill of Satie's Parade, Poulenc's Les Mamelles de Tirésias and Ravel's L'Enfant et les sortilèges at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1981. He was 83 when he first conducted Wagner's Ring cycle, back in Seattle. In 1988 he introduced Debussy's _Pelléas et Mélisande_to a Russian audience. And his third recording of _Gaîté Parisienne_was made when he was 92. He was 93 when he told me:

I could go on conducting, though my right leg is dragging a bit. But you have to finish some time or other and let the young folk have their chance.

Rosenthal closed his career crowned in glory, regularly visited by researchers wanting to ask about the great names with whom he had rubbed shoulders almost a century before. He took some solace in the gradual rediscovery of his own music, though was peeved that it was the lighter scores that tended to attract attention. His 13 orchestral scores - among them a symphony, from 1949 - await regular performance, as do the five for chorus and orchestra, although the style, something akin to Poulenc with teeth, would certainly appeal to a wide audience. His response to the observation that his music was very French could have come from Ravel:

Yes, but it was none of my doing - it just happened. I like things to be claire and I am, I think, quite formal. You should always know why you are doing what you are trying to do . . . A great musician must be careful to be himself.

Martin Anderson

This interview was recorded on the telephone on September 9, 1985. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1985, 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 1986 and published in the Tenth Anniversary Edition of The Massenet Newsletterin January, 1987. It was slightly re-edited and updated, and was posted on this website in August of 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.