Joseph Schwantner Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . (original) (raw)

Composer Joseph Schwantner

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Born in Chicago in 1943, Joseph Schwantner received his musical and academic training at the Chicago Conservatory and Northwestern University. While developing a profile as a leading American composer, he also served on the faculties of The Juilliard School, Eastman School of Music and the Yale School of Music, simultaneously establishing himself as a sought after composition instructor.

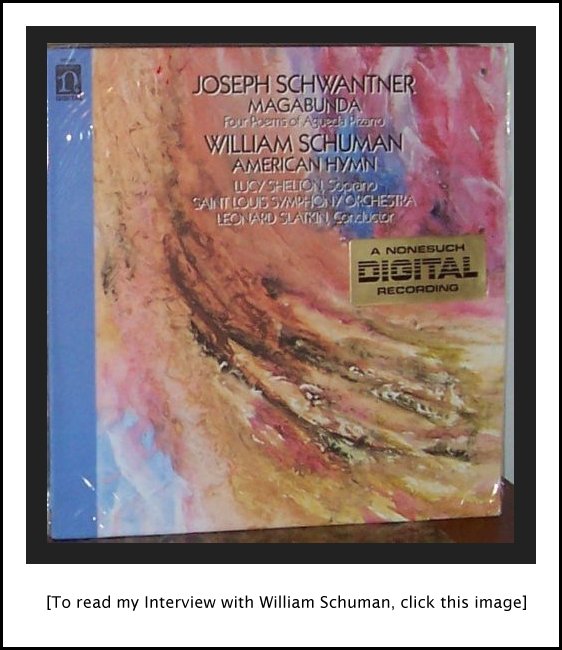

Schwantner’s compositional career has been marked by numerous distinctions and awards. His early accolades include three BMI Student Composer Awards, the Bearns Prize, a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, and many other awards, grants and fellowships. In 1979 his orchestral composition Aftertones of Infinity won the Pulitzer Prize. In 1985 his life and music were the focus of a television documentary entitled Soundings, produced by WGBH in Boston for national broadcast. That same year his work, Magabunda “Four Poems of Agueda Pizarro,” recorded on Nonesuch Records by the St. Louis Symphony, was nominated for a 1985 Grammy Award in the category “Best New Classical Composition,” and his A Sudden Rainbow, also recorded on Nonesuch by the St. Louis Symphony, received a 1987 Grammy nomination for “Best Classical Composition.” Schwantner is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Schwantner’s Percussion Concerto, among the most often performed of contemporary concert works, was commissioned for the 150th anniversary season of the New York Philharmonic. He has also been commissioned by numerous other leading orchestras and organizations including the National Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, San Diego Symphony, Chamber Music America, Fromm Music Foundation, Naumburg Foundation, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, among many others.

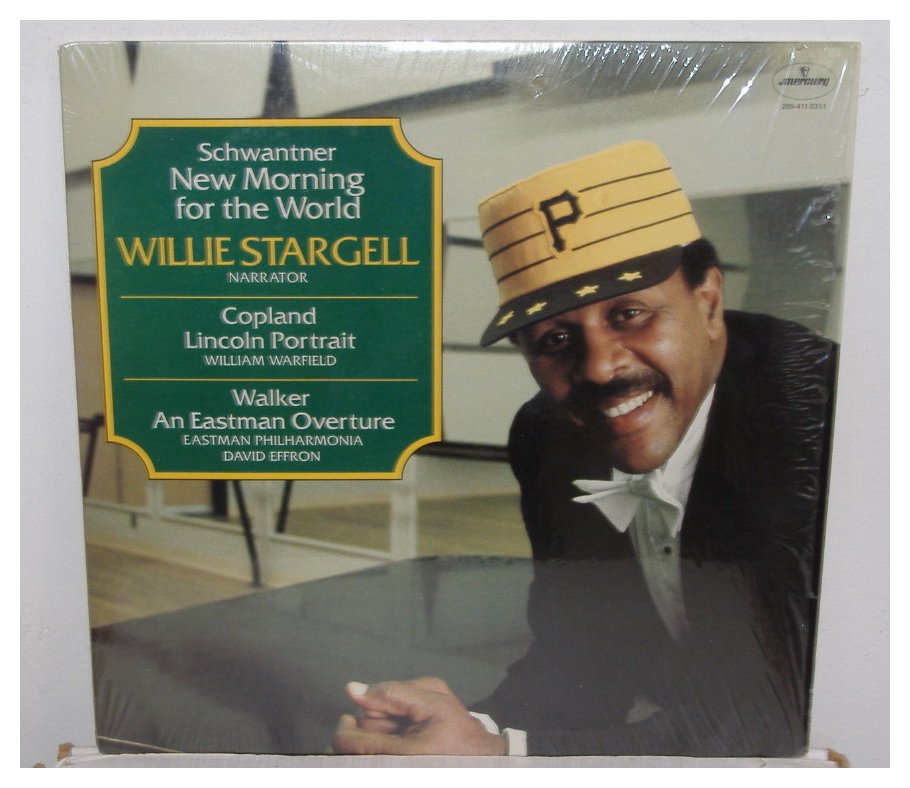

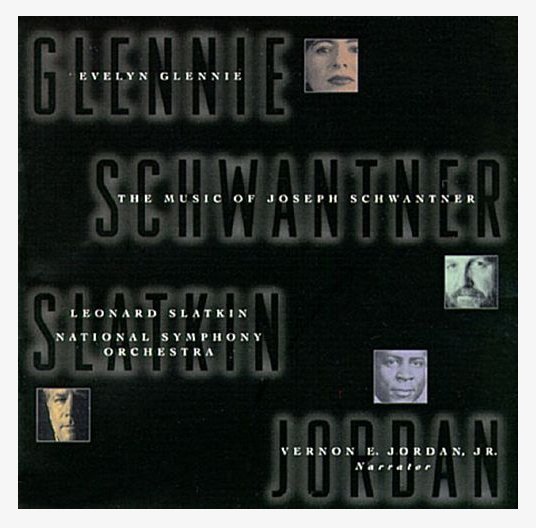

Schwantner has enjoyed particular success in the orchestral world. After winning the Pulitzer Prize for Aftertones of Infinity, Schwantner composed New Morning for the World: Daybreak of Freedomon words from Martin Luther King, Jr. for narrator and orchestra, which has since entered the standard repertory of orchestras nationwide. His Percussion Concerto has garnered over one hundred performances since its 1995 premiere and is one of the most performed concert works of the past decade. His music is noted for its deft implementation of luminous color and fluctuating rhythms in a dramatic and unique style, heard in such signature works as the Percussion Concerto, New Morning for the World, and Magabunda, among others. Schwantner’s Morning’s Embrace was commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra and premiered at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC on February 23, 2006. The Washington Post praised its “delicate timbres” and “unique and original” sound. His music has been championed by such conductors as Leonard Slatkin, Marin Alsop, Andrew Litton, Hugh Wolff and artists including Evelyn Glennie, Sharon Isbin and Anne Akiko Meyers, among many others.

In January 2007, Schwantner was selected as the composer for the second cycle of Ford Made in America, the nation's largest commissioning consortium of orchestras spearheaded by the League of American Orchestras and Meet the Composer. The resulting work, Chasing Light…received its world premiere with the Reno Chamber Orchestra in September of 2008 and completed its tour of over fifty orchestras in all fifty states in the Fall of 2010. The composer's more recent works include: Silver Halo, commissioned by Flute Force for their 25th anniversary season in 2007; and The Poet’s Hour… for violin and string orchestra commissioned by the Seattle Symphony in honor of music director Gerard Schwarz’s farewell season.

Other recent commissions for the composer include the world premiere by Eighth Blackbird in October 2006 of Rhiannon’s Blackbirds, which the group commissioned and included on their nine-month United States tour during the 2006-07 season. In August 2009, Schwantner saw the world premiere of Looking Backfor flute and piano, commissioned by former students and colleagues of Samuel Baron to commemorate his memory. Looking Back was performed by flutist Alexa Still and pianist Stephen Gosling at the National Flute Association’s 37th Annual Convention in New York City. Schwantner's highly anticipated follow up to his revered Percussion Concerto,Concerto No. 2, received its world premiere with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra and Hans Graf as the headline event at the Percussive Arts Society's 50th annual convention. The music of Joseph Schwantner is published by Schott Helicon Music.

-- From the Schott-Music website

-- Names which are links in this box and in the interview below, refer to interviews by Bruce Duffie elsewhere on this website

In March of 2002, Schwantner was back in Chicago for performances of his Percussion Concerto with Evelyn Glennie and Leonard Slatkin conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. At that time I had the chance to sit down and have a conversation with the composer. Here is that encounter . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Are you proud to be an American composer of concert music?

Joseph Schwantner: Absolutely!

BD: Is there something special about being a composer of concert music as we head now into this new millennium?

JS: I don’t think it’s any different than before 2001, actually. My life is my work, and I’ve had the great good fortune of working with some wonderful musicians, as we will hear this week with Evelyn Glennie and Leonard Slatkin. I’ve had a longstanding relation with Leonard that goes back to the early eighties. I was Composer-in-Residence for the St. Louis Symphony. That started in 1982 and I remained there until 1985, but our relationship has continued. He’s continued to perform my music, so I’m forever grateful to him for his interest and concern.

BD: Is this something that a composer should seek out

— a conductor who will champion his music?

JS: I don’t know if you seek it out. It’s something that happened in my life, and it’s certainly been rewarding. It’s very interesting how he first came to my music. I had written a work in 1977 called …and the mountains rising nowhere. It’s a work for wind ensemble, and somehow it got into his hands. It actually interested him to the point of considering doing it with the St. Louis Symphony.

BD: The winds of the orchestra, or re-scored for the whole ensemble?

JS: It’s for woodwinds, brass and percussion, and one of the things about the piece that is unusual is that it asks for the musicians to kind of sing, and to whistle, and to engage in a lot of sounds other than simply playing their regular instruments. This is the kind of thing that you can do quite readily with a university ensemble, but not something that’s often done with a professional group. He determined, after considering this, that in order to do this piece — this was in the early eighties — that it would cost some eight or nine-thousand dollars in extra fees that would have to be paid, because the musicians would get doubling expenses, and it couldn’t be justified with a piece that was only eleven minutes long. So he didn’t do that work, obviously, but he did ask my publisher if there was another work of this composer. It was a work called Aftertones of Infinity, which he then did decide to perform in St. Louis, and performed it with many orchestras all over the world. Then he invited me down to become Composer-in-Residence with St. Louis Symphony, so that’s when the relationship really started.

BD: I assume this is something that a composer looks for

— to get performances beyond the first one?

JS: Oh, absolutely! This percussion concerto has been done literally hundreds of times now since its inception in 1995.

JS: Oh, absolutely! This percussion concerto has been done literally hundreds of times now since its inception in 1995.

BD: And been recorded?

JS: It has been recorded by the National Symphony with Leonard and Evelyn, and continues to get very frequent performances. I’m really delighted to see that.

BD: Do you know why?

JS: Well, it seems like percussionists like to play it. That’s one thing, and it seems to get a good reception from musicians and audiences. So I think that’s why. It’s a fairly accessible work. It’s a demanding work, certainly, on the musician’s part, and Evelyn just does remarkable things with the music at this point in time. I can’t even count the number of times that she’s played it, and certainly it’s one of the major pieces she’s doing this year. She’s doing it with Chicago and she’s doing it with the L.A. Orchestra, and it goes on and on and on and on. So it’s really still an active part, one of the active pieces in her repertoire.

BD: You don’t travel with the piece all the time, do you?

JS: Oh, no. I’m from Chicago, so I just decided that it would be wonderful to come back. It all feels like home to me, and to hear Leonard and Evelyn play with this wonderful orchestra.

BD: So there had to be something to get you to a specific performance.

JS: I always like to be with my friends, and certainly, to hear her play is always a very arresting experience for me. One of the things is that when I hear her play, she always brings a new twist to it. It’s really her piece at this point in time. She’s done it so much, and there’s a comfort level that she has with the piece. And obviously she’s an extraordinarily commanding player. No question about it. It’s always exciting for me to hear what new vision she brings to the piece.

BD: Did you write it for her?

JS: No. It was written for Christopher Lamb, who was the principal percussionist in the New York Philharmonic. It was written for their 150th Anniversary, and they had commissioned a number of composers to write for their principal players. I remember Lamb was a student back in the mid-seventies at the Eastman School of Music, where I taught for thirty years, and I recall what an exciting young performer he was. So when the opportunity came to write a concerto for percussion with him, I immediately leapt at the opportunity. It received its premiere performances in the mid-nineties, and the thing I’ve been very grateful about is not only the support of many percussionists, but what I’m finding is that many principal percussionists in orchestras are now picking up the piece. I’m really delighted to see that happen, actually. So some pieces do have life after the premiere, and happily for me this is one of my works that seems to continues to get quite a lot of play.

BD: Once it gets a lot of play, I assume that in percussion circles that’s one of the pieces where they say, “Oh, of course you play the Schwantner, don’t you?”

JS: Yes, I think that happens. Let me give you an example. For twenty years, the BBC has had a Young Musicians Competition, and for all those years the winners were typically cellists and pianists and violinists. Then, I guess maybe it was three years ago, a young British percussionist named Adrian Spillett was in the final running of this competition. It’s an all-U.K. competition, and it was my piece that he was able to perform. He was the first percussionist ever to receive first prize with this piece, and it was broadcast nationally. I just heard recently that now, yet another young British percussionist is in the final running of this year’s BBC Young Musicians Competition with this piece again! [Laughs] So it will be broadcast, again, all over the U.K. and I’m delighted about that.

BD: Let me turn the coin over. Will there come a time when you wish that people would let this go, and play another piece of yours?

JS: Well, I have a large enough body of orchestral work. I’ve devoted a quarter of a century of my life to thinking about the orchestra and writing for the orchestra. I have a number of pieces that orchestras regularly engage. I have a work for narrator and orchestra called New Morning for the World, based on texts of Martin Luther King, that gets performed quite a lot during the month of January. In fact, for my publisher it’s rather problematic because you get this wave of performances all on January 15th, obviously Martin Luther King’s birthday. That’s a piece I wrote in 1983, and as far as I can tell is pretty much a staple in the standard repertoire of the orchestras these days. It still gets a lot of play, but then, on the other hand, you write a piece and you never know the fortunes of your work. It’s not anything that a composer really can calculate. Some pieces seem to have a life of their own, and others receive their premiere, and thereafter collect a lot of dust on your shelf.

To read my Interview with William Warfield, click HERE

To read my Interview with George Walker, click HERE

BD: Being a composer with a fairly large repertoire of pieces that are done, does that put more pressure on you when you write a new piece

— that it be another one to go into this line?

JS: I don’t think so. You always try to do your best, obviously, and to move ahead with each new piece. Each new piece brings new challenges, but actually it’s interesting. Sometimes commissioning bodies would like to have another percussion concerto, or some other work that you’ve written. I don’t think that’s so uncommon. They’d like to have another winner if they could. It’s not always in the cards, but you do your best, obviously, and try to engage through whatever project with the full measure of your integrity as much as possible, and give them your all.

BD: I assume there is a certain amount of clamor for new works from your pen. How do you decide yes, I will do this, or no, I will turn that one aside?

JS: I often decide if it’s a project that really seems to challenge me and deal with issues that I haven’t dealt with before. I came back from Dallas several weeks ago, where I wrote a piece for organ and orchestra. I had been with the Dallas Symphony in 1999 when I wrote a horn concerto for them, and they had the most magnificent organ in the Meyerson Symphony Hall. They have a triennial international organ competition, and the winner of that competition gets not only a substantial stipend, but the opportunity to play a subscription series with the Dallas Symphony. In addition to playing a new work, I was the composer chosen to write this work. I had never written for organ and orchestra before, so right there it was a challenge that I knew that I should consider. Having heard the organ in 1999, I was just bowled over by the power and the grandeur of this magnificent instrument. So from a musical point of view, I immediately got very excited about the prospects of this piece, as well as the opportunity to write a work for the fine orchestra there.

BD: Does this, then, encourage you to write a few more organ pieces?

JS: Maybe, sometime in the future. It’s a complicated instrument, with an extraordinary range of timbres and colors and articulations. My sense is that you never really can wrap your mind around the possibilities of that instrument.

BD: You’re used to orchestrating. Is that at all the same as registration?

JS: I did do a fair amount of registration in the piece. Also it was certainly helpful to have the input of the organist, the soloist at hand, James Diaz, to provide his invaluable insights. But yes, I’d be more than happy to try my hand at it again. I feel comfortable, certainly, as a result of working on this piece. But I think my general perspective is that I want to make music with my friends, and continue going through life making music as best I can, and then increasing my circle of friends! So far that’s been a good strategy for me.

BD: You get the commissions and you decide you’re going to them, and you line them up.

JS: Right.

BD: Do you ever leave a little time just to write the piece that you want to do, that nobody asks you for?

JS: That’s an interesting question. I have, throughout my adult life, been in this position of responding to initiatives by others. People want pieces from me to the point where it seems that I can operate fairly efficiently that way. If the commission is open-ended, I will try to steer it in a way that meets my own musical needs. But I seem to be that kind of musician that I’m able to engage whatever idea is posed to me. If I find it interesting, then I can usually go with it. My life, really, is a series of meeting deadlines. [Laughs] It goes from one piece to the next, essentially, and so far, I’ve been fairly responsible in being able to meet those deadlines. I’m sure there’ll be a time when I can’t meet them, and sometimes it’s come very close to not meeting a deadline.

JS: That’s an interesting question. I have, throughout my adult life, been in this position of responding to initiatives by others. People want pieces from me to the point where it seems that I can operate fairly efficiently that way. If the commission is open-ended, I will try to steer it in a way that meets my own musical needs. But I seem to be that kind of musician that I’m able to engage whatever idea is posed to me. If I find it interesting, then I can usually go with it. My life, really, is a series of meeting deadlines. [Laughs] It goes from one piece to the next, essentially, and so far, I’ve been fairly responsible in being able to meet those deadlines. I’m sure there’ll be a time when I can’t meet them, and sometimes it’s come very close to not meeting a deadline.

BD: The ink is still wet upon delivery?

JS: Yes, almost. It’s actually come pretty close once in a while, but I feel fairly responsible about that in trying to meet my obligations as a composer.

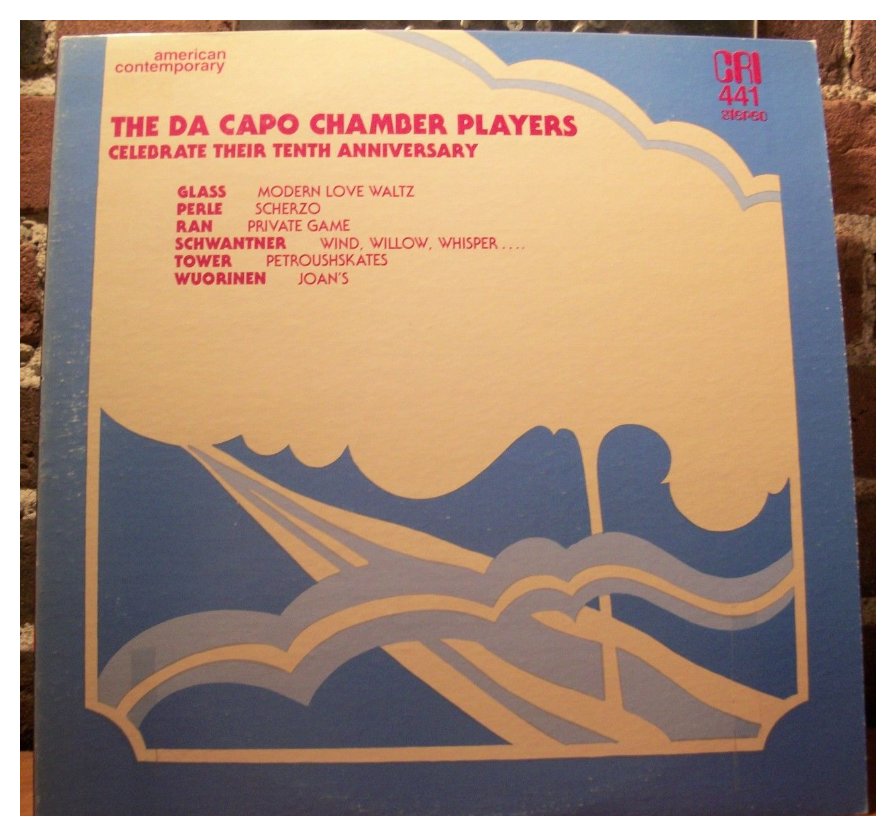

BD: As a professional composer who’s done it so often, when you get a commission do you know about how long it will take you to write the piece? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, also see my interview with Lucy Shelton.]

JS: Yes, I do. I work fairly consistently. I wouldn’t say that I work continually at white heat speed, but I know how fast and how much time I need for whatever the project is, and I factor that into my schedule. It doesn’t always work, but you do the best you can so that you have some breathing space between one work and another. Often times a double bar is drawn and I immediately have to move on to the next project. In one sense, when I look over my body of work over twenty-some years or so, I often have the feeling that ideas that somehow ferment in one piece are not always fully considered in that work necessarily, but then spill over into another piece. It seems to me that the double bar at the end of a work is almost a matter of convenience, and there’s a larger tapestry of ideas that I might be tapping into as a musician that move from one work to another. I wouldn’t want to be specific about that, but that’s the sense that I have. There’s a larger continuity of ideas, I think. I don’t think that’s uncommon for composers to be involved with their music over a long span of time, where certain kinds of musical issues would arise, and to some extent you engage them in a particular work but maybe haven’t completely come full circle until ten years in the future at some point.

BD: I don’t want you to be specific, but would it be possible for you to organize a few all-Schwantner concerts with those themes in line?

JS: Yes, it might be, actually. I suppose that might be possible. I’m not sure people would want that, but I’m the kind of musician and audience member who likes a lot of diversity. I have rather catholic tastes, and so I wouldn’t want one of any composer, probably, on a concert. But I suppose that if I were forced to do that, I could come up with the kind of scenario that might make some musical sense to me. Whether that would be apparent to an audience, I don’t know.

BD: When you’re sitting there at your desk, are you conscious of the audience at all?

JS: Oh, yes! I know that there is going to be some kind of an audience. I don’t know really who the audience is, though, if you think about it. For a good number of years I’ve been mainly concentrating on orchestral music, so I do have a sense of generally who those folks are, and I certainly have a fairly good sense of who the musicians are. If there’s any group of people that I’m most concerned with, obviously it’s the musicians. If they don’t understand the work, if they can’t engage it in a full way, then how can they possibly translate my ideas and my vision for music to an audience? So I have to communicate with them. I have to be clear. My intentions have to be clear to them, and only then can they complete that circle. When you talk about audiences, you have to ask what audiences are you talking about. There are audiences who are highly informed about contemporary music, for example, a kind of highly specialized audiences, and then there are more general audiences that you’d find at a symphony concert

— people who certainly care about music, to the extent that they’re willing to pay $95.00 for a ticket. But they’re at a considerable disadvantage when it comes to contemporary music. The composers’ names are often quite unfamiliar to them. The music is even less familiar, and they only have, maybe, one opportunity that evening to make sense of what they’re going to hear. So I understand that, and despite my understanding of that, at the end of the day I still just do what I have to do, and hope that I can reach some of them with that one hearing.

BD: You want to be part of this procession of musical history?

JS: Oh, I think so. It’s part of the continuity of a thousand years of western musical history. We’re a footnote in that, maybe, but yes, sure! Of course.

BD: Do you have any advice for audiences who come to a concert that has a work of yours on it?

JS: If one’s serious about listening it takes a lot of work, and listening is not an easy endeavor, it seems to me. If you take it seriously, then you should come to the concert with a sense of adventure and open ears, and if the opportunity allows, try to find in recording of music of the composer that you’re going to hear on that evening. Take some positive steps to become acquainted with the composer’s work so that it’s not a completely alien landscape when you first approach this new piece. One of the problems has to do with the whole issue of programming, and how orchestras decide on programming. That’s a very complicated matter. It’s not only the vision of the music director, but there are a lot of other parties that partake in those decisions about what pieces end up on these programs. It has to do with the soloists that are contracted, as well as a number of other factors that go into making a symphony season.

BD: Perhaps this is a dangerous question, but is it your responsibility at all to make sure that you contribute positively to the bottom line?

JS: No, I don’t think so. I don’t know what that bottom line is. Most ensembles that I know are run in the red, so it’s not about the bottom line. There is no bottom line. It seems that concert music has never made a profit in the history of the world, and that’s not likely to change. There will be subsidies necessary in order to keep ensembles like the Chicago Symphony afloat and healthy and thriving. So no, I don’t think about that at all. It’s not my responsibility. My responsibility is to the musicians and to myself to write the best music that I’m capable of.

BD: Is there a balance in your music — or in music overall — between art and entertainment?

JS: [Laughs] Oh, boy. Well, I guess it’s all show business, isn’t it? At the end of the day, it’s all about show business. I would like to think that what I do has some interest to some listeners. It’s very interesting, actually. I came back from Dallas several weeks ago having heard this new work called September Canticle for Organ and Orchestra. The next day I must have received about twelve or thirteen e-mails from people who had been in the audience! I was getting immediate feedback from them in a way that I don’t recall ten years ago, when e-mail was only for computer-types. That really astonished me. Over the next few days, as I stayed in Dallas for the subsequent performances on the subscription series, I was getting increasing e-mail about this from listeners who wanted to tell me how they felt about the music. That really astonished me, actually, that they felt it important enough to let me know, and they actually sought out my website and e-mail address and all that, and decided to tell me how they felt and reacted.

BD: Was most of it positive?

JS: Yes, it really was. It was really astonishing. In fact, I don’t recall one negative one. There was one who said, “New music is not my cup of tea and I just had to let you know.” It really was all positive, and that delighted me to no end.

BD: Have you ever been in the position when someone’s come to you and said, “How can you write that garbage?”

JS: No, not really. I think sometimes people just keep it to themselves.

BD: There are a lot of composers who experience that because of their style.

JS: Maybe so; could be someone who writes in a severe style. I think my music is fairly direct. At least I’m trying to write as directly and clearly and succinctly as possible.

BD; Was this a conscious decision on your part to write this way, or is this just where it took you?

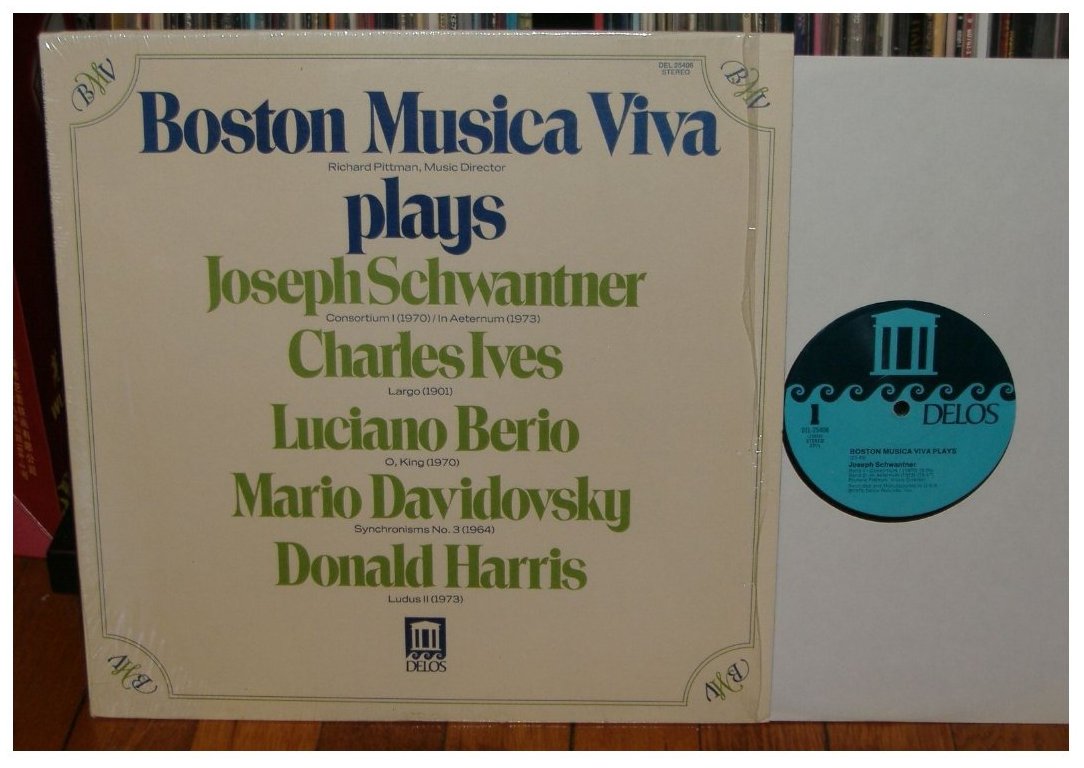

JS: In my early work as a young composer who just finished graduate school at Northwestern, I was interested in serial music and the most kind of demanding musical rhetoric played by highly specialized chamber ensembles, and there was a very limited audience for that kind of music, obviously. I’m part of a generation of composers, who, in the mid-seventies really began to look around and realize that a way to move forward was not only to abandon the past, but to embrace it. You think of composers like George Rochberg and George Crumb, and others who began to decide that the past would not be denied. And as a result of that kind of thinking, of kind of inclusionary thinking, my style changed and I grew out of the academic part of my life. That’s important for any artist. Academia gives you skills and techniques and procedures, and a body of work that is important, but at some point in time you have to find out who you are as an artist, and move beyond your academic training. That’s what happened to me in the mid-to-later part of the seventies and into the eighties.

To read my Interviews with Philip Glass, click HERE

To read my Interview with Geroge Perle, click HERE

To read my Interviews with Shulamit Ran, click HERE

To read my Interview with Joan Tower, click HERE

To read my Interview with Charles Wuorinen, click HERE

BD: Have you found out who you are, or are you still discovering it?

JS: You always do. You always hope there’s a part of you that is childlike and where music is magic. It’s really true and you can’t explain it. On the other hand, as a professor of many years, I’m in the business of talking about music in very specific and detailed ways with my graduate students. But the bottom line is we don’t really know where this stuff comes from, actually. On one hand there’s a part of me that always wants to come to the new work in a very innocent way, and on the other hand, intellectually I understand how my music operates and can talk about it in any manner of detail. The best music, to my way of thinking, is part intuition, as well as the rational mind controlling the musical events. I would hope that after hearing the work, it leaves something for yet another hearing; that the music is deep enough and rich enough that it may call you back for another sampling; and if it doesn’t, well, maybe you don’t need to go there. Some music is like that. It has an immediate kind of accessibility on the surface, bur there’s not much underneath it to draw you back.

BD: Is this what makes music great

— the depth that it has?

JS: I think so. You hear the late Beethoven string quartets and have a feeling you could listen to them forever and never completely understand them. And each time you re-engage that music you’re rewarded with new riches, new musical and sonic riches that you hadn’t heard previously.

BD: We’re kind of dancing around it, so let me ask a real easy question. What’s the purpose of music?

JS: For me it’s the way I live my life through my work, and that’s a very idiosyncratic way to lead a life as a creative artist through music. It also has to do with sharing. I want to share what I do with others. I can’t play all the instruments in the orchestra, so I need to have the support system of an ensemble of musicians, and we join together in this endeavor of making music. We need audiences, obviously, to hopefully appreciate what it is that we do. But even if there weren’t audiences, I would probably do it, even if it was only a matter of writing pieces for piano for myself. As a young boy I was interested in poetry. I was interested in art. I was interested in music, and when I look back at it, I was interested in performing. As I look back at that early life, I could have gone in a number of different directions, quite frankly, but it was a young boy who was just full of ideas. I don’t know where that comes from. I was the kind of personality that couldn’t leave things the way they were. As an example, I remember when I was about eight years old I studied the guitar. I played the guitar. I had this wonderful teacher, and he would give me assignments. The next week, after working very hard on my assignment, I would come and play for him, and I would never play what was on the page. I would always elaborate and add things to it. For a while he put up with that, and finally he became quite stern and said, “Look, I really want you to play what I’ve assigned to you.” I just never felt like that was something that was interesting to me. Finally he said, “Look, if you want to write, if you want to do this elaboration, go ahead, but let’s make this a separate activity.” Well, that’s all he needed to say, and I was all about the business of writing these little pieces. Then he was fine. He would talk about harmony and melody and musical form and the textural aspects of the instrument, and I knew very early on that this was the way I wanted to make music. I didn’t just want to recreate music. I wanted to make music.

BD: Now let’s leap ahead fifty years.

JS: It hasn’t changed at all. I’m that same little boy, actually.

BD: But are you expecting your performers who do your music to put their little bits in as well?

JS: Well, no. Let me say, it depends. When it comes to a symphony orchestra, obviously with 98 to 103 musicians, if they all went in their own direction it would be chaos; so, no. But on the other hand, in this percussion concerto there is a spot toward the end where there is a simple fermata, a place where the orchestra just stops, and there’s the most marvelous kind of creative cadenza played by Evelyn Glennie. She just makes it up. I wouldn’t probably do that if I wrote a flute concerto, and expected the flutist to have those kinds of skills. But certainly, I generally rely on percussionists to come up with something interesting, and that she always does. So to that extent I’ve given a very substantial piece of the music to the soloist, to let her bring her own ideas into the piece, and that seems to work out just fine.

JS: Well, no. Let me say, it depends. When it comes to a symphony orchestra, obviously with 98 to 103 musicians, if they all went in their own direction it would be chaos; so, no. But on the other hand, in this percussion concerto there is a spot toward the end where there is a simple fermata, a place where the orchestra just stops, and there’s the most marvelous kind of creative cadenza played by Evelyn Glennie. She just makes it up. I wouldn’t probably do that if I wrote a flute concerto, and expected the flutist to have those kinds of skills. But certainly, I generally rely on percussionists to come up with something interesting, and that she always does. So to that extent I’ve given a very substantial piece of the music to the soloist, to let her bring her own ideas into the piece, and that seems to work out just fine.

BD: You say you wouldn’t want the flutist to do that kind of thing?

JS: I would doubt that the flutist would have the training to improvise on the spot. For percussionists, that’s their bread and butter, obviously.

BD: A jazz flutist might be able to do it.

JS: A jazz flutist might, yes, that’s true. I said it would depend on the musician. I wouldn’t categorically say no flutist could ever create a cadenza. With this recent piece that I wrote for Dallas, there is a place toward the end where there is a cadenza for the organist. In fact, organists do quite a lot of study on improvising, so I thought that I could take a chance and see if this would work. If it didn’t work, I could always have them take the bridge right over to the conclusion of the music. The organist did a quite extraordinary job of coming up with a really interesting cadenza, so I’m emboldened to think that my music can be a framework for this kind of creative energy that musicians can consider when performing the work.

BD: When you write a concerto, are the cadenzas optional?

JS: In the case of the percussion concerto, no. In the case of the organ concerto, yes. I would say it would be an option.

BD: So you put in a cadenza that can be used, but if the guy or gal can do a better job or a more interesting job, that would be acceptable?

JS: It would depend on if I’m there and have some input, obviously. If I’m not there then it’s still a possibility for the musician to consider.

BD: I just wondered how much of a straight-jacket you put the performer in.

JS: Quite considerable, obviously, when you’re dealing with that many musicians. If I were to do another concerto specifically for Evelyn Glennie, now that I’ve had this experience of working with her over the last six years or so, I could probably write a piece that would have very little information on her part, and just let her go. That might be a really interesting thing to see what would happen.

BD: Could you go all the way back and just simply write a figured bass?

JS: It might not even be that, actually. Just let her respond to her kind of sonic environments and see what she would come up with. I know she’d come up with something really interesting. Not only that, but it would provide a kind of sonic landscape by which she could re-think her role from performance to performance, as opposed to simply following the prescription or scenario that I’ve outlined by being very, very specific from beginning to end.

BD: Do you ever re-think your role as composer?

JS: No, I don’t think so. I think I’m an old dog that is kind of set in my ways now.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] No new tricks up your sleeve?

JS: Well, hopefully. Sometimes the tricks are very personal and would not mean very much to anyone else. But each day I get up and I’m still excited about the work, and I look forward to the next day’s opportunity to spend time with whatever project I’m working on. I suppose when it no longer becomes exciting, I’ll take up carpentry or something else to kind of occupy my time. But as long as it still remains fresh and interesting and invigorates my life, I want to continue doing it. And when I can add good friends and good musicians into the mix, it’s even more exciting. So like I said before, I still feel like I’m that little boy who couldn’t wait for the next guitar lesson to show my teacher what I had learned over that week. I guess that’s what it’s all about. I want to show people that I have learned something in my life and I’m willing to share it. It’s ultimately about sharing your ideas and your music-making with your friends.

BD: Are you where you want to be at this point in your career?

JS: I don’t think about career so much. I’ve been around long enough so I’m just really interested in writing music. You can’t control careers very well, and I don’t know what it means, anyway. I really don’t. I’m pretty secure with what I know I want to do. Whether anyone else is interested is another matter, so I’ll leave the career business to other people to consider, quite frankly.

BD: Has there been any little lingering impact on you, having won the Pulitzer Prize?

JS: I haven’t thought about that for years. Back in 1979 when I received it, there was a kind of increased visibility in terms of name recognition, but at the end of the day, if people are not interested in your music, it doesn’t matter what kind of laundry list of accolades and awards you have. They’re simply not going to play it. I don’t care; it’s just not going to happen. So no, I don’t think that’s really important at all. I’m glad that I received it, sure. I’m glad, as a young composer in his thirties, to receive that consideration, but over and above that it doesn’t guarantee anything, quite frankly.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

JS: Oh, I really am, actually. I’m generally an optimistic person, but I traveled all over this country and all over the world hearing my work, and listening to just extraordinary music-making in this country. It doesn’t happen only in Boston or New York or Chicago or L.A. It happens in Laramie, Wyoming, and Coeur D’Alene, Idaho. It’s quite astonishing when you think about it. It’s clear we live in a great country that has developed extraordinary musicians, with the Eastmans and the Juilliards and the Northwesterns and the Indianas of the world turning out really fine young musicians. In my lifetime I’ve seen an extraordinary raising of the bar, technically, in terms of the capacity of young musicians to engage music. So I remain on that level very optimistic. Am I optimistic about the future of the arts in our country and support for the arts? That’s a different story. But when dealing with the young musicians, as I have as a teacher for many, many years, I’m only optimistic about the future.

BD: The performers have obviously gotten better year by year.

JS: Absolutely!

BD: Have the composers gotten better year by year?

JS: Oh, no question! No question! Technically, I don’t think there’s any question about it. I work with an extraordinary group of young composers at Yale, and they have the technical capacity and imagination that is astonishing for musicians at such a tender age. It’s really remarkable, and I feel grateful to have the opportunity to work with them. So I remain an eternal optimist about the future of music, especially in our country. It is wonderful to see results of that every day and hear my own work played, as well as great music making all over.

BD: Thank you for coming back to your home city.

JS: Thank you. Thank you very much.

To read my Interview with Luciano Berio, click HERE

To read my Interview with Mario Davidovsky, click HERE

To read my Interview with Donald Harris, click HERE

© 2002 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 13, 2002. Portions were broadcast on WNUR two months later, and again in 2005. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information abouthis grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.