Sir Georg Solti Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . (original) (raw)

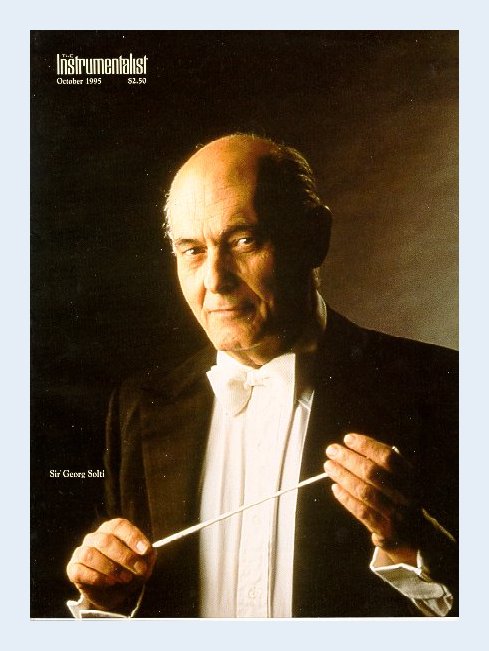

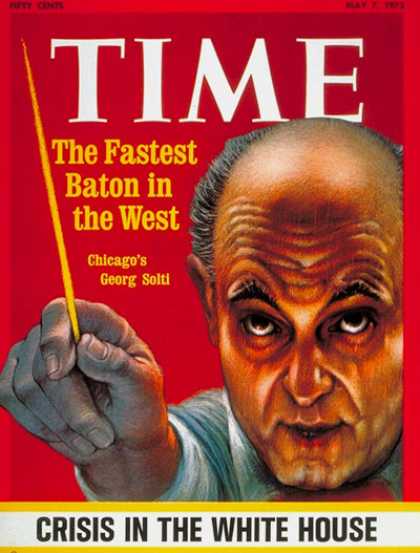

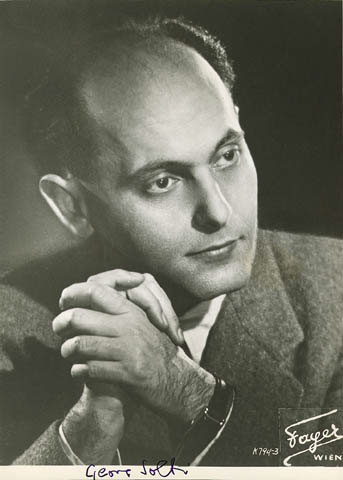

Conductor Sir Georg Solti

Two Conversations with Bruce Duffie

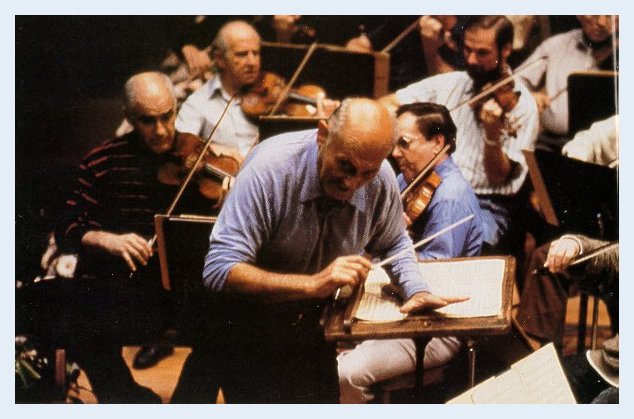

Though the spelling remained Georg, Solti (later Sir Georg) insisted it be pronounced George. He was a human dynamo, always doing many things and keeping them all running at top speed. His performances were known for rhythmic precision, and though his beat looked somewhat clumsy, it was easy to follow and made for exact entrances and cut-offs.

He was kind to the press, but kept us all at a distance. He did not particularly enjoy doing interviews, and only allowed a few minutes for anyone. I was privileged to have been given two such audiences, and the results were used on several occasions, all of which are enumerated in the credit at the very end of this presentation.

What follows is a compilation of the two meetings which was published as the Cover Article in The Instrumentalist magazine in October, 1995. It has been slightly re-edited; a few additional details have been added and the links have been placed in the introduction.

Born in Budapest in 1912, Sir Georg Solti studied piano, composition, and conducting with Bartók, Dohnányi, Kodály, and Leo Weiner. His concert debut was as a pianist, but shortly thereafter he became the conductor of the Budapest Opera. In 1935 he assisted Bruno Walter at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1936-37 Toscanini selected Solti as one of his assistants, and can be heard playing the gockenspiel in the performances of Mozart

’s Magic Flute. Before the outbreak of World War II, Solti went to Switzerland and turned again to the piano for his livelihood. In 1946 the American military government invited him to conduct a performance of Beethoven’s Fidelioin Munich. This led to an appointment as music director of the Bavarian State Opera. He later served as music director of the Frankfurt Opera and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. He first led the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at the Ravinia Festival in 1954, and later returned for guest performances. He was with the Lyric Opera of Chicago for two seasons. In 1956 he conducted Salomewith Inge Borkh, Die Walkürewith Birgit Nilsson [see my interview with Birgit Nilsson], Paul Schoeffler and Ardis Krainik as Rossweisse, Don Giovanni with Eleanor Steber and Nicola Rossi-Lemeni and La Forza del Destino with Renata Tebaldi, Richard Tucker and Ardis Krainik as Curra [see my interview with Ardis Krainik]; the following season he conducted The Marriage of Figaro with Steber and Walter Berry [see my interview with Walter Berry], Un Ballo in Maschera and Don Carloboth with Jussi Bjoerling and Anita Cerquetti. It was not until December 1965 that he conducted during the regular season at Orchestra Hall. From 1969 to 1991 he was music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and currently is music director laureate. He is also conductor emeritus of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, having been principal conductor from 1979 to 1984.

Bruce Duffie: Having conducted orchestras all over the world, can you rate the Chicago Symphony along with some of the other great orchestras?

Sir Georg Solti: Of course I am not quite objective, but in my mind there are maybe two major competitors, and that’s all. I regard three orchestras

— Chicago, Berlin Philharmonic and Vienna Philharmonic — in the same class. These are the three top orchestras in the world, and it is a question of taste as to which you prefer. Naturally you know my preference. It is a great privilege because in the last three months I have conducted all three of these orchestras, so I am probably best equipped to answer this question. They are all three marvelous orchestras. In some, this section is better here or better there, but the total impression is that each is a joy to conduct. There are many other first-class orchestras, some I know and some I don’t know, but I suppose these are the three top orchestras in the world today. It is not a football league so I won’t rank them one, two, three,

BD: When you conduct the Vienna Philharmonic or the Berlin Philharmonic, do you have enough time to put your stamp on the music you are playing?

Sir Georg: Of course; [with a sly grin] I have the best post office in the business!

BD: Well, when you prepare for a concert, is all your work done in the rehearsals or do you leave something for the spark of the evening?

BD: Well, when you prepare for a concert, is all your work done in the rehearsals or do you leave something for the spark of the evening?

Sir Georg: Of course, there is always something remaining for the inspiration of the musicians and myself on the evening. There is something magical, that chemistry happens always. More or less always, but not the major part! First is the hard work, and then comes something extra. But you can

’t have something extra without hard work.

BD: What do you see in the future of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra?

Sir Georg: I wish that we maintain that standard, and simply that we work on quality and not on quantity. There is a danger to all American orchestras to play more and more concerts because they need money. That could be a dangerous situation because the more you play, the more you lose the quality. With more and more performances there are less and less rehearsals. That is a danger which I clearly see and I have to fight. We are very lucky

— and I am speaking entirely about the Chicago situation — we are tremendously lucky. We are augmenting our listening public, we are augmenting our subscriptions, so the payroll must be met and we are doing it very well.

BD: In playing the same repertoire again and again, how do you keep the great pieces alive and vibrant for every performance?

Sir Georg: I do not play the same repertoire again and again. That’s a mistake. I am always leaving the major pieces aside for years. I won’t touch most pieces for 10 years. Then I start anew; I forget what I did 10 years ago. It is a very long time.

BD: You get a clean score?

Sir Georg: I buy a new score usually, and then I begin to restudy and let it come through. That’s the only way to keep it fresh. A piece you play again and again and again is a Xerox copy.

BD: Is the record you make today of a piece you just played last night going to be a Xerox copy?

Sir Georg: No, but similar. Very similar. I have a very clear idea of how the music should sound

— rightly or wrongly — and I aim for that clear idea.

BD: Does your clear idea of a piece change over a period of 10, 20, 30, 40 years?

Sir Georg: Yes, because my mind is changing.

Sir Georg: Yes, because my mind is changing.

BD: Is it improving?

Sir Georg: I hope so.

BD: Are there any pieces that you’ve played that you feel you’ve plumbed all the depths?

Sir Georg: There is no piece in this world that you can say that about; only a silly musician could say, “Yes, I made it, I don’t want anything more, I am wonderful.” A decent musician would never say that. You always aim for something better. You always aim for a better performance from yourself.

BD: Is it special for you to have worked with this one orchestra for 20 seasons?

Sir Georg: Yes. I have never been anywhere in my whole conducting career 20 years. The longest has always been 10 years. I love this orchestra very much; that is the reason why I stay here. In another three years I will bow out.

BD: But you won

’t abandon us completely, will you?

Sir Georg: No, no, no! I will come back as some sort of emeritus conductor once a year for three or four weeks, something like that, but I can

not take as much transatlantic traveling.

BD: Do you prepare differently for operas on stage than you do for operas in concert?

Sir Georg: Yes, because acoustically the conditions are different. On stage you are full of compromises. The timing is different, the balance is different. It is all very different for a concert. A good stage performance is wonderful, a bad stage performance is terrible. One must be very careful when one does an opera on stage nowadays. I love opera in a concert version because you concentrate on the musical content, and this is so essential. I simply love it and I do it from time to time.

BD: In opera, what should be the balance between music and drama?

Sir Georg: There should always be an internal balance with staging, music, and movements. All the time you compromise; you have to. There is no fixed ideal of what should be soft or loud. For example, if the singer is near the back of the stage, they have to give a little more sound and you have to keep the orchestra down. This is a compromise which you learn the hard way if you have time. If you have the sense of drama, if you have a sense of theater, that makes an operatic conductor. If you know about the stage, if you know about what an opera is; lighting, movements, everything; these all belong to that. Only then can you be a good operatic conductor. You cannot come off the street and conduct an opera; you must grow up in the opera house and you must know what it is.

Sir Georg: There should always be an internal balance with staging, music, and movements. All the time you compromise; you have to. There is no fixed ideal of what should be soft or loud. For example, if the singer is near the back of the stage, they have to give a little more sound and you have to keep the orchestra down. This is a compromise which you learn the hard way if you have time. If you have the sense of drama, if you have a sense of theater, that makes an operatic conductor. If you know about the stage, if you know about what an opera is; lighting, movements, everything; these all belong to that. Only then can you be a good operatic conductor. You cannot come off the street and conduct an opera; you must grow up in the opera house and you must know what it is.

BD: Now they seem to come from the concert halls instead.

Sir Georg: Not many. The really good ones are growing up in the opera houses.

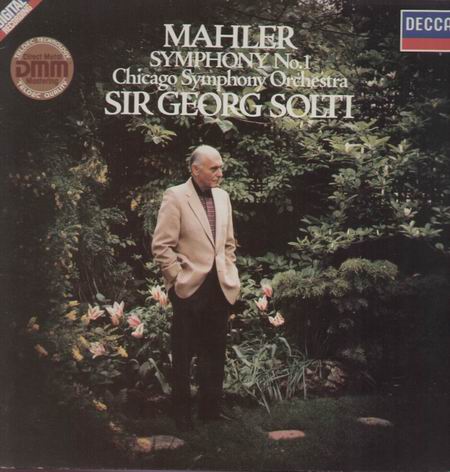

BD: Are you pleased with all of the recordings you’ve made over the years?

Sir Georg: I am pleased with a few, but not all. Nobody’s pleased with all of their work. I’m quite pleased with a few, and I

’malways pleased with the latest ones because that’s my latest child; then it is forgotten because I never really listen to my old records.

BD: When you do listen to a recording of a concert from 10 or 20 years ago, are you pleased or displeased?

Sir Georg: I never listen to my records.

BD: If someone comes up and says that they heard this record you made in 1958 and they like it...

Sir Georg: I think that is marvelous. I’m not taking anybody’s pleasure away. It’s very important that one records. I try to record all the major pieces three times in my lifetime: as a young man, a middle-age man, and as an old conductor. This is very important because these will be three very different aspects of what I have done. There are some Beethoven symphonies I have recorded several times now – very early in my conducting life, at the beginning of my Chicago life, and now 15 or 20 years later. That makes sense.

BD: Do you do anything differently in the recording studio than in the concert hall?

Sir Georg: Essentially my aim is the same: try to perform the music as well as possible and try to have a sort of magnetism. We also create a spirit of mind that reminds us that what we are playing will last a long time. For a concert we play and it’s gone, but a recording is something that will last maybe 20, 30, 40, God knows how many years. That responsibility gives the performance an added something special. Something special always remains within the inspiration of the musicians and myself during a concert. It’s a magical chemistry, but to have that chemistry, it takes hard work first in the rehearsal. Then there’s a chance to add something extra; you cannot have the extra without hard work. I like recording but it is a tremendous hardship because a recording session consists of playing, rehearsing, playing, and making tapes. When the orchestra has a break, I listen to the tapes, and this is more important than the actual making to find out what I like and don’t like. I have to quickly make up my mind what to play again and why and how. It

’s three or four hours non-stop!

BD: Is there any chance in all of the cutting or splicing that a record becomes too technically perfect?

Sir Georg: We don’t cut and splice anymore, that is old-fashioned. I record movement by movement, playing each one three, four, or five times. I don’t believe in splicing. One little detail will not make the recording better even if we corrected it. The spirit of the entire movement counts, not the little bits of it. If we have a good day on a movement and there is one wrong note or mistake, I might correct that and not ruin the entire tape of a good movement. We put in a bar or two, but that is all. If I feel that two bars here should go, and another two bars, and another two bars, then forget it – start over and do it again.

BD: What makes a piece of music great as opposed to mediocre, or perhaps even worse?

Sir Georg: I think it is very easy to define that. A good composition makes music that sounds great naturally. A very good performance helps. When you play even the most wonderful piece of music badly, you can take away some of its greatness but you cannot kill it. Even the lousiest performance cannot kill Beethoven’sNinth Symphony. You cannot! A good performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphonylifts you up into heaven.

BD: What are the ingredients of great music?

Sir Georg: A great composition, naturally. Great human geniuses create great music and only a few of them come into this world. I think of Mozart, who lived only 36 years and left behind hundreds of incredible, rich, marvelous pieces; but we don’t know anything about who Mozart was. Nobody knows where he was buried or what was the cause of his death, only that he was 36 years old when he died.

Sir Georg: A great composition, naturally. Great human geniuses create great music and only a few of them come into this world. I think of Mozart, who lived only 36 years and left behind hundreds of incredible, rich, marvelous pieces; but we don’t know anything about who Mozart was. Nobody knows where he was buried or what was the cause of his death, only that he was 36 years old when he died.

BD: Do we really need to know those details?

Sir Georg: No. All we really need to know is that this genius, or angel, came to this world and left behind an incredible amount of music. That is enough. Mozart teaches us to believe in God because if it was possible for an angel to come down and leave so much music behind, then there must be a superpower above who created that. I don’t believe it’s something that happened by chance.

BD: Are there other composers who have this divine spirit?

Sir Georg: Yes. Of course there are many other composers, but Mozart came to mind because of his short life span. There was a lot of indifference in the world then. Later, in the 19th century, a composer became much more a subject of adoration and admiration, but I believe that when Mozart died only a few hundred or maybe a few thousand people knew of him, but no more than that.

BD: Is it part of your responsibility to keep the flame of Mozart alive?

Sir Georg: It’s all good musicians’ responsibility, not only mine. Every musician has a duty to keep not only Mozart, but and all of the other geniuses alive. There are dozens.

BD: Not hundreds?

Sir Georg: Probably not hundreds of greatcomposers. Dozens. I never counted, so I don

’t really know where to stop counting.

BD: With so many thousands of composers trying to write music, is there a break at some point between the great, the good, and the mediocre?

Sir Georg: You cannot locate such a point. There’s a marvelous production called Amadeus, but the play is really about Salieri. There is this wonderful scene when Salieri breaks down and says to God, “What did I do? I’ve been the best son of yours, I always follow the church; why haven’t I got the talent of Mozart? Why did you not give me that?” Why? There’s no answer for that.

BD: Should we then, on occasion, play the music of Salieri?

Sir Georg: I suppose, yes. Why not? Although, unfortunately, it’s very mediocre. I know only a little about Salieri’s music. It is very well written, but it doesn’t have the genius of Mozart.

BD: What about your special affinity for Haydn and Bartók?

Sir Georg: I have a special affinity for all major composers. I am not a specialist. Both of these are great composers. Bartók is a great 20th century composer. I have a special affinity, naturally, for the language of Bartók, coming from the same country. I knew him personally, and that of course makes for some special affinity. Haydn is an old favorite of mine. He was one of the greatest composers who ever lived, but I refuse to be stamped as a specialist. I like music from Vivaldi to Schoenberg, everything.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

Sir Georg: I have always been optimistic about the future of music and always will be. This leads to the question of what will happen if nobody writes any music today that will last through the 21st century. The answer is that we have enough good music from the last 400 years that will last at least another 400 years. Why should I bother with what happens in 2420?

BD: Should we not continue to expand the repertoire?

Sir Georg: Of course we should continue to expand the repertoire, and I believe we will expand the repertoire all the time. But assume the worst; there is such an incredible amount of great music written in the last 400 years that I can’t believe we’ll get bored and won’t feel like playing it anymore.

BD: What advice do you have for young conductors?

Sir Georg: The only advice one can give is to work as hard as possible; it is the only way to achieve something that you want. Don’t rest on your laurels and don’t wake in the morning and say, “I was wonderful yesterday.” See your shortcomings, strive to improve, and if you are talented it will arrive. You always arrive. I don

’t believe we have any neglected talent in the 20th century. That’s the only advice I suggest. Don’t despair, it is sometimes very difficult to go on and work, but you will learn.

BD: Do you follow that advice in your own career?

BD: Do you follow that advice in your own career?

Sir Georg: Yes, of course; I am the living example of that.

BD: What are the shortcomings, if any, of Sir Georg Solti?

Sir Georg: I am not a living example of shortcomings, I am a living example of a difficult career

– the most difficult one that you can have. I was 34 years old when I first-time conducted. That, for any normal conductor, is much too late. It is better to start at 18 or 19 or 20 because there are certain technical problems you have to overcome as early as possible. I started at 34 because of the gentleman called Mr. Adolf Hitler. A bigger shortcoming than that cannot be, and I overcame that one with hard work and suffering and problems.BD: What advice do you have for audiences that come to concerts or operas?

Sir Georg: Prepare yourself for a concert. Listen to a record; nowadays this is so easy. Don’t hear everything for the first time, because the first time, one doesn’t like anything. Go, and at least hear it for the second time; you will find it much more enjoyable. American audiences still differ from European audiences but they are improving. They are getting much more sophisticated thanks to the radio and records that spread musical knowledge.

BD: What is the ultimate purpose of music in society?

Sir Georg: The ultimate purpose is definitely a sort of mental and physical enjoyment. Art has, in every sphere, an unbelievable effect on those who really want to enjoy it either visually looking at marvelous things, or by listening. It lifts the spirit and makes you a better human being. There’s real enjoyment in good music, and by that I mean everything, not only 19th– or 18th–century music, Beethoven or Brahms but also Gershwin. Good music puts you in a better frame of mind, puts you in another, different world. If you learn how to listen, if you learn how to enjoy music, this is one of the most marvelous spiritual upliftings that you can have. This is not only for professionals for but also amateurs and the public. Real enjoyment of music comes from knowing a piece. If you listen to a piece 2, 3, 4, or 15 times, you’ll find it better and better and more enjoyable. That is the advice that I give to any listening public. Remember at a concert not to listen for the first time – it’s no good. It is easy to broaden knowledge, so buy a gramophone record or listen to the radio and then go to concerts. It is not that the record is better than the concert. Nothing surpasses live music. Prepare yourself and you’ll find a fantastic new dimension.

BD: One last question: Is conducting fun?

Sir Georg: Fun??? Oh, great fun. I wouldn

’t do it otherwise. It’s the greatest fun. Good music is the greatest joy of my life.

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

------- ------- ------- -------

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

Bruce Duffie has interviewed nearly 1,000 musicians for his radio show on WNIB, Classical 97, in Chicago. As a host of hundreds of full-length opera broadcasts, Duffie knows the material well and lectures for the Lyric Opera and teaches adult education classes in the Chicago area. Duffie earned a bachelor of music education degree from Illinois Wesleyan University and a master of music degree from Northwestern University and taught for two years before turning to radio.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

These interviews were recorded in Chicago on May 11 and October 10 of 1988. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB later that year and again in 1990, 1991, 1992 and 1997. A portion was also featured on the nationally syndicated series Lincoln’s Music in Americaduring the last week of October, 1988. The transcription was made and used as the cover article in The Instrumentalist magazine in October of 1995. It was slightly re-edited in 2009 and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.