Walter Berry Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

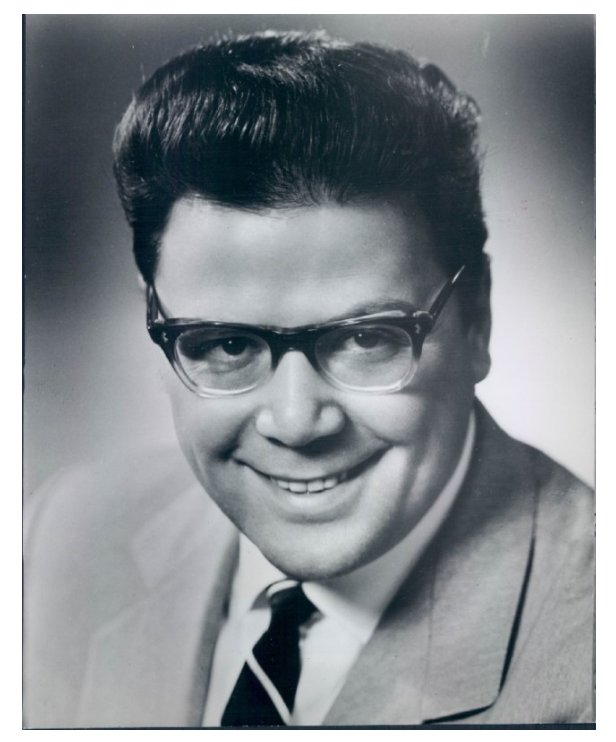

Bass - Baritone Walter Berry

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

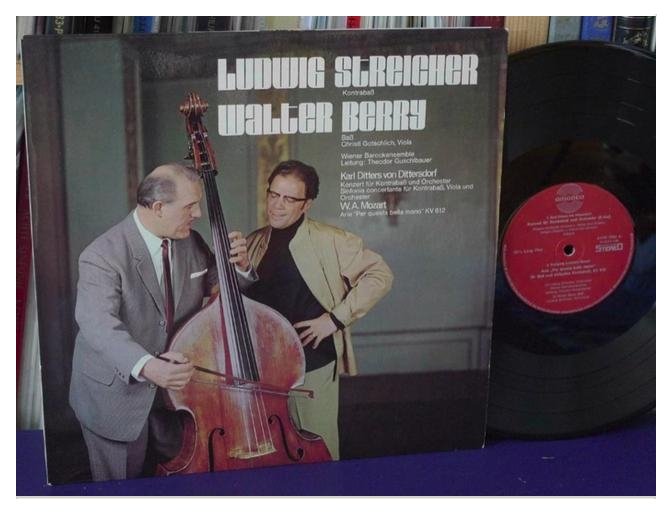

One of a very special group of singers who defined the Mozart style in the 1950s and 60s, Walter Berry had a large repertoire and gave impressive performances around the world. His artistry is preserved on many recordings of large and small roles. Details of his life are given in the obituary which can be seen at the bottom of this page.

Wanting to present his ideas as well as his voice, he did me the honor of going out on a limb to do his first telephone interview in a foreign language! His English was very good and on only a couple of occasions did I have to prompt him or translate a word or idea. Very kind and always jovial, he often sang illustrative phrases to demonstrate his points.

When we spoke in June of 1985, he was in San Fransciso for performances as Alberich in The Ring, so that is why there is an emphasis on the Wagner repertoire. But we also talked about his other roles and interests, and he began by noting his American debut in Chicago . . . . .

Walter Berry

: First of all, may I say something which is in my heart? I have such beautiful memories to Chicago. I sang so many operas in that beautiful hall on Wacker Drive when Carol Fox was the boss of the house. Back in 1957, a very young Walter Berry made his American debut in The Marriage of Figaroas Figaro in Chicago. The cast included Tito Gobbi as the Count and Giulietta Simionato as Cherubino, Eleanor Steber was the Countess and my Susannah was Anna Moffo. I really have precious memories.

Bruce Duffie: Was the conductor Krips?

WB: I don’t know now, because I have sung with so many in so many cities that I mix it up. I’m sure that Krips was the conductor later on of the Così Fan Tutte we did there with Elizabeth Schwarzkopf and Christa Ludwig, and he conducted the Figaro, too, in a later season. [Note: Berry

’s recollections are correct. As can be seen in the chart below, he sang in Chicago in six seasons.]

Walter Berry at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1957 - [American Debut] Marriage of Figaro with Steber, Moffo, Simionato, Gobbi; Solti

1959 - Così Fan Tutte with Schwarzkopf, Ludwig, Simoneau, Corena, Stahlman; Krips/Matačič

1960 - Marriage of Figaro with Schwarzkopf, Streich, Ludwig, Waechter; Krips

1961 - Così Fan Tutte with Schwarzkopf, Ludwig, Simoneau, Cesari, Stahlman; Maag

Don Giovanni with Waechter, Stich-Randall, Della Casa/Schwarzkopf, Simoneau; Maag

Fidelio [Don Fernando] with Nilsson, Vickers, Hotter, Wildermann, Seefried; Maag

1970 - Rosenkavalier [Opening Night] with Ludwig, Minton, Brooks; Dohnányi

1975 - Fidelio [Pizarro] withJones/Wagemann, Vickers, Crass, Wise; Ahronovich

-- [Note: Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this site. BD]

BD

: Then let’s start with Mozart. Tell me the secret of singing his music.

WB: [Laughs] If you go into that, it is also connected with Chicago. Because of the circumstances in Vienna, we couldn’t play in the big opera house on the Ring because they reopened the house only in 1955. So we played in the small theater and we developed a certain style, a Mozart style, which was first of all connected very much with the singers at this time. These were Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, Irmgard Seefried, Erich Kunz, Anton Dermota, Paul Schoeffler... This was an incredible ensemble. Together with Karl Böhm and Josef Krips, they developed that style, that Mozart style, which fitted wonderfully in the small halls there. When I came as a young and un-experienced singer to Chicago to sing my first Figaro there, I tried to produce that same sound, or thought I had to do the same Mozart style I was taught in Vienna. But it was not the right style for the big house.

BD: I’ve always wondered if Mozart should be played in a house as large as ours.

WB: Yes. Then you have to give much more voice. If I can give a little example of, we used to sing [sings lightly], but you have to sing [sings more powerfully]. So coming for the same point, you have to make it louder. To get the same style you have to give much more. But there’s one thing. Even in the recitativo, you should never be sloppy with Mozart. Every note he has written is so important because he was a genius, and he knows exactly why he has written that longer or shorter. So even if it is kind of parlando, it should follow the notes and the rhythm. Mozart has rhythm. An Italian told me that it is amazing, as an Italian, to see how Mozart has donned the Italian language when you follow the way he has composed the language in the music.

WB: Yes. Then you have to give much more voice. If I can give a little example of, we used to sing [sings lightly], but you have to sing [sings more powerfully]. So coming for the same point, you have to make it louder. To get the same style you have to give much more. But there’s one thing. Even in the recitativo, you should never be sloppy with Mozart. Every note he has written is so important because he was a genius, and he knows exactly why he has written that longer or shorter. So even if it is kind of parlando, it should follow the notes and the rhythm. Mozart has rhythm. An Italian told me that it is amazing, as an Italian, to see how Mozart has donned the Italian language when you follow the way he has composed the language in the music.

BD: So he really knew it from his heart, then?

WB: Yes. That’s what he meant. He didn’t just speak Italian. He really knows it from the heart, what kind of language he’s composing in. And of course, in the German operas, it’s the same thing.

BD: Does Mozart work in translation? You have recorded Figaro in both German and Italian.

WB: In my opinion, not so much. If you say, as Leporello for example, [sings in Italian], it’s really Italian. If you say that in German, [sings in German], it is more, let’s say, the northern part of Europe and it becomes a touch of Lortzing, which I don’t like so much because it is not the original. The thing you are doing now in the United States with the subtitles during the performance, I think this is very good.

BD: You think this is the right compromise, then?

WB: I think that is a wonderful compromise, especially when we are doing such long operas asSiegfried lasting for four and a half or five hours. For an audience who doesn’t understand the language, the same story is repeated and repeated over and over again, so it is a very good thing they can follow the words. I was in the hall and I saw it. It is not disturbing at all.

BD: Do you think this will catch on in Europe, or is it particularly an American phenomenon?

WB: I will try to do as much as possible to convince them that it is a very good compromise to use the subtitles.

BD: Do you think that having it had on the television for a number of years has gotten people used to that idea?

WB: Yes, and then there’s another problem. As I mentioned, I love it to be given in the original language. It fits so well with the music. If you take Bluebeard’s Castle, it is such a difference if you sing it in English or German or any other language, or in Hungarian. I have recorded and sung it often, very often in the Hungarian language, and this is much better. It is a difference if you say [sings in German] or if you say [sings in Hungarian]. This is Hungary! I love it, but when the young people go to the opera for the first time and are sitting there not used to going to opera, maybe doesn’t love it. They have to fall in love with it and this is very difficult when he’s sitting there for three and four hours and he cannot follow what is going on onstage. He might be bored. The moment he can read the words, maybe the first time he is more concentrated on reading the words. Later on he forgets about reading because he knows it, and he could easily fall in love with opera, I think.

BD: How much preparation do you as an artist expect on the part of the audience?

WB: It depends. There are some operas that are much easier going, but things like The Ring of the Nibelung that we are doing here, need some kind of preparation from the audience. At least they should read it. They should talk about it so they can enjoy much more, let’s say, levels of the performance. There is one level which is just the outside action. Sometimes there’s not too much going on onstage in these long Wagnerian operas. But you can also enjoy the music, the different themes. You can enjoy the psychological things. It is so wonderful when one character is talking about something, but the orchestra says, “No, no, you have in mind something else.” It’s what isn’t explained, and not the words in his mouth.

BD: The psychological thoughts?

WB: Yes. Then you can enjoy much more, and you get much more out of it.

BD: Are recordings a good way to come to opera, or are they not really the way to understand it?

WB: I think recordings are a good way to come to opera, but you have to know that there is a difference between the recording and what’s going on the house. This is a great danger, I really think. It is the counterpart of us, our own recordings! [Laughs] You cannot expect to hear, in the hall, the same volume of the voice as you can expect to hear in your stereo set at home. You cannot expect an orchestra playing after five hours in the pit to be as fresh as they are on the recording, because they start the session every day new and fresh. You have to know that you are listening to a record. On the other hand, the excitement is going on in the house — it gives you very much. So for the education, to get into it, it is good that you are familiar with the music and what is going on. But you have to take in mind that this is the recording and that is the performance at the opera house.

BD: Do you feel that you are competing against your own recordings if you’re singing a role that you have already recorded?

WB: Sometimes, yes. [Both laugh] Yes, sure. I know this is a real problem. It has become better now because when we first sang, we had the microphone TEN inches away from our mouth. Now the way the recordings are done is so different, and the engineers and the musicians which do the recordings know to make it a little bit more like it sounds in the opera house. The microphones are not that close anymore, and there is a difference in the recordings and the sound. It is mixed better with the orchestra because sometimes it is not really necessary that you hear the voice standing out of the orchestra. Sometimes even the voice is just an instrument playing with the orchestra. There are some pieces in The Ring

where it is not possible to hear the singer for a few bars, but in general Wagner has composed it very much for the voice. He has not composed against the voice.

BD: [Somewhat surprised] Really??? You would tell that even to the tenor singing Siegfried?

WB: Yes. It’s just that he has to sustain the time, but it is written very good for the voice. Wagner uses always the full range of the voice, the top and the lower edges and the middle, and he mixes it very much so you can relax in between. The orchestra plays very loud the moment the singer is not singing, but mostly, when the singer starts, the orchestra goes down. This is very much the genius done by Wagner. Of course, the problem is that you have to sing for such a long time in the opera.

BD: But you really think that Wagner took care to preserve his voices?

WB: Yes, I think very much so. In my opinion, it is not what Anna Russell said on the recording — which is so funny, and I love it

— that the singer has to bellow through the orchestra... [Laughs] ...which would be a wrong “bellow-canto.” [Continues laughing]

BD: A “bellow canto”! [Laughs] So it’s the responsibility, then, of the conductor to make sure that the singer can be heard through this wall of sound?

WB: Of course. This is the work of the conductor, to bring out all the dramatic which is going on in the music without covering the singers too much. But there are some pieces where, as I mentioned, the voice is just part in the orchestra, and it is not really necessary for, let’s say, ten bars, that you really can hear the singer’s voice. If you hear the timbre, that’s enough.

BD: But now, if you have the subtitles going on, you’ll still get the text.

WB: That’s right. You can follow. You can follow it. So this is also an advantage.

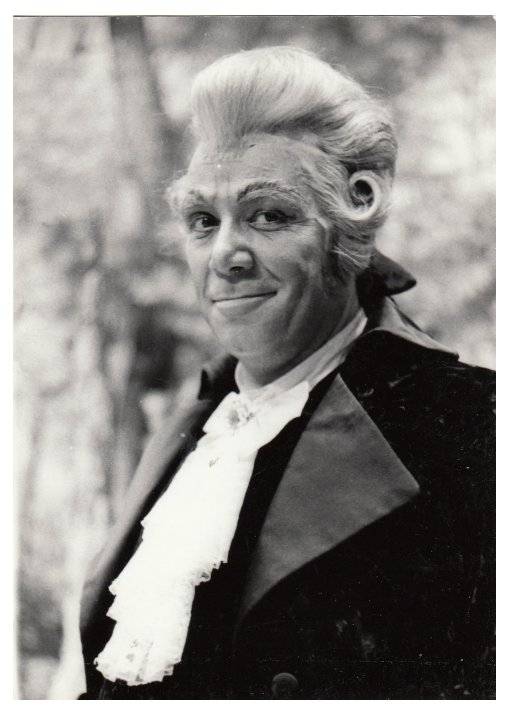

BD: Tell me about the character of Alberich. Just how evil is he?

WB: In my opinion

— which is maybe as personal as Bernard Shaw’s opinions on The Ring — when Alberich in Rheingold comes out in the first scene with the Rhinemaidens, he’s really looking for love, for true love, the kind of love you have also to your mother, to your brother and to your father. It is not that he’s looking to all this for sex. He says at the end of this scene that he gives up love. He doesn’t give up sex, because he has later on his son Hagen.

BD: So you separate the two, then?

WB: Yes. I think he really comes out saying, “Oh, they are so beautiful! If they just could hold me in their hands and cuddle me and be nice to me...” Then when he sees how badly the Rhinemaidens treat him, and how bad all of them treat him because he doesn’t look too nice, then he really sees the chance either to have a kind of love they gave him or to have the power of the universe in his hands. So he gives up love for the power, which he’s not intelligent enough to handle, and which happens very often. He’s in possession of the power. He’s not stupid, but not intelligent enough to handle it in the right way.

BD: But if one of the Rhinemaidens had even been nice to him a little bit, then the whole story would not have taken place?

BD: But if one of the Rhinemaidens had even been nice to him a little bit, then the whole story would not have taken place?

WB: Yes, that’s what I think. And it was Wagner’s problem. His own problem is very much involved in that, too, because he might have been bothered from the desires of his body. In every opera he’s always looking for the real, true love, and always something happens, as it happened in Wagner’s life.

BD: So it’s very autobiographical.

WB: I think so. I also think that Wagner has an incredible sense of humor, which comes out very often in the opera. That’s very obvious when Siegfried tries to blow on that reed in the second act and it doesn’t work. [Both laugh]

BD: If The Ring is autobiographical, which part is Wagner? Is Wagner Wotan or is Wagner Siegfried?

WB: Wagner is everyone onstage who is struggling for love and hoping to be freed in the soul; to be good and knowing he’s not good. So many parts in The Ring are really evil. I wanted just to mention that in my opinion, Alberich is the only one who gives up something to get something. The others are just stealing and taking away, breaking contracts, and they’re really mean persons in The Ring.

BD: Wotan is not giving up his family happiness for his lust for power?

WB: Wotan has a spear, and Alberich says, “Here written on the spear are so many rules you have broken.” Just think of the conversation Wotan has with his wife, Fricka. It’s not nice, what they are saying to each other...Symphonica domestica! [Both laugh]

BD: What’s the relationship between Alberich and his son, Hagen? Is Hagen more evil than Alberich?

WB: No. It shows very clearly in Götterdämmerungthat Hagen is a kind of an instrument in the hands of his father. He’s the one who can do what Alberich isn’t able to do anymore. We even do it here. For Alberich in the RheingoldI have a wig with full black hair. Later on, in Siegfried, my hair is already worn out and there is gray, and I have no hair at all, a bald wig for Götterdämmerung. It’s like Samson — when you take away his hair he has no power and no strength anymore. I think it’s a little bit the same thing with Alberich. The more it goes on, Alberich is just hate. It’s the true hate which destroys himself. He’s not able to do anything. He’s freezing. He’s old. He’s just hate! So his son, Hagen, is in his full strength. In that first scene of Act Two in Götterdämmerung, Alberich is telling Hagen what to do. It’s obvious that this scene has happened very often before. It’s not only this one scene. It’s very often that he appears in the dreams of Hagen. Hagen is a kind of Macbeth to his father.

BD: Do you view the characters of Wotan and Fricka as gods or as people?

WB: They have to be gods because there has to be the difference between them and the human beings. They behave very much as the rest of the world, but they disappear at the end, and somehow there has to be a difference. Keep in mind that Wotan just lifts his hands and somebody’s dead. In the first place, Wagner thought of doing a god world and the world of the others, of the human beings. But it might have slid out of his hand, or it might have been his intention to show that even the gods are behaving like the others.

BD: So even the gods are human?

WB: Like normal.

BD: How human does Wotan become, especially in Siegfried?

WB: In Siegfried he’s a very wise man already. Maybe Wotan himself thinks, “To hell with being God; you have to gain wisdom with the age.”

BD: Do you enjoy playing the part of Alberich?

WB: Yes. To have the opportunity, as I have it here, to play Alberich in all three operas is very rare. I can show this development downwards Alberich is undergoing to myself and to the audience. I think this is very good. I like it very much. Besides, it is an incredible amount of work we have to do here. It’s not so easy. I just had last night, the Götterdämmerung, and I had Siegfried, and Rheingold in a row.

BD: You’re not just singing in a Ring, but you’re singing in a couple of overlapping cycles. You do Siegfried then Rheingold then Götterdämmerung. Does that confuse you at all?

WB: No, it cannot because I have my scores with me. During the day, when I go to bed in the afternoon, I take my music with me and I’m reading and I get into it. You have to be able — and thank God I am able — to forget that I sang last night another opera, maybe Götterdämmerung and now I have to do Rheingold. So there is the end of it and the beginning.

BD: I just wondered if it would be better for you to just sing one cycle complete and then begin again.

WB: I had the opportunity, but also I have to mix it sometimes. The order now wasSiegfried, Rheingold, then Götterdäammerung, but that doesn’t disturb me. In my mind I know which way it has to go, and if it is now on Tuesday and Wednesday and Thursday, or if it is Wednesday, Thursday, Tuesday, it doesn’t matter. I know which direction to go.

BD: When you’re onstage, do you become the character or are you still Walter Berry portraying the character?

WB: In my whole career I always tried to become the character. There are many very good actors. There are types like, let’s say, John Wayne used to be. Whatever he did, he was John Wayne. And there are other actors, like Charles Laughton and so, that try to get into the character. This is a different kind of thing. Sometimes they sell themselves better by selling the type they are, but I always try to get into the character. There is, of course, a great deal of Walter Berry because you are not just a character onstage you are playing. You have to think of so many things at the same second — if you are right, together with the conductor, if the sound is okay, if the word is right, if you stay in the right place. There are so many things that have to put you down to earth which is good and which is necessary. You cannot be carried away by the character. But as much as possible, I try to think and to act in the way that man I have to do onstage now would be.

BD: Then how long after the performance does it take before you become just Walter Berry again?

WB: At least as long as the performance lasts, which is usually up to three or four hours. I cannot fall asleep immediately after the performance. When the performance finishes at midnight, I will be awake until about four o’clock before I calm down. This is always, and I’m doing it for such a long time, but the performance is always an incredible excitement for me. No, I cannot take it easy. I cannot take it cool. Maybe I love it too much...

BD: Let’s move onto another of the Wagner parts. Tell me about Kurwenal. What kind of a man is he?

WB: Kurwenal is not a character you can talk hours about because he doesn’t have those many different levels. He’s just a very good companion to Tristan. He could completely give or do everything for Tristan, and he’s living through Tristan. It is a little bit like Don Giovanni. As long as Don Giovanni’s alive, everybody surrounding him is alive, too. The moment Don Giovanni’s dead, the opera is finished.

BD: So then Kurwenal is sort of like Tristan’s Leporello?

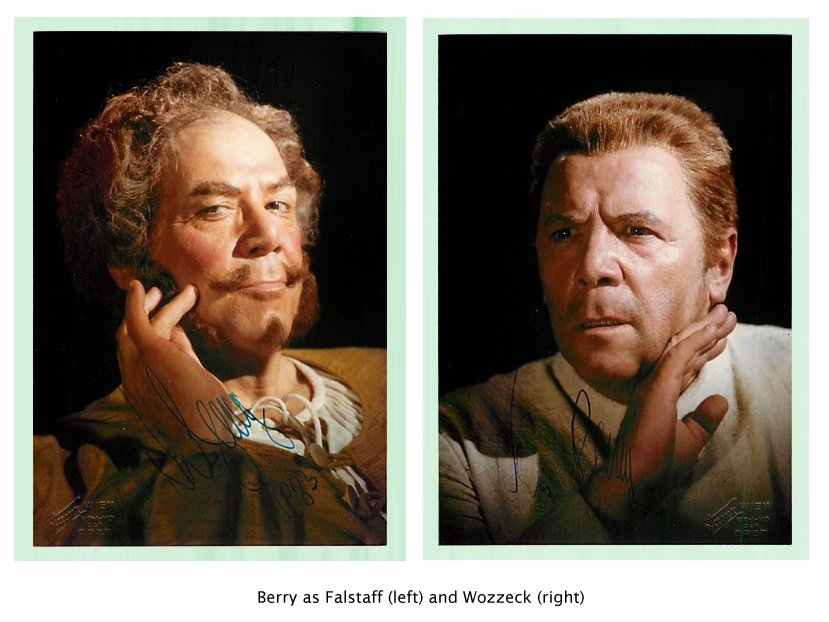

WB: Yes. Let’s say in a very serious way. It’s just my opinion. I did Kurwenal, and it was not a part like, let’s say, Wozzeck. I love parts you can change in. Alberich changes from the first scene to Nibelheim and so on, like Wozzeck who changes very much during the opera. But parts like Escamillo? They are always the same. It’s boring for me.

BD: You’d rather do someone that develops?

WB: Yes. That’s much more interesting.

BD: Does that have any influence on how you select which roles you sing? Do you try to only sing interesting roles?

WB: Mmmmm... I didn’t, but maybe I do now. When you’re right in the middle of your career you have to do so many roles, and they ask you to do it here and here and here, and to do everything — I think very often of Escamillo, for example — you do it because you are young and you do everything. You become more selective later on. Now when they offer me a part and I think this part is not of real interest for me, for my inner side, I wouldn’t do it.

BD: You’ve done a number of contemporary operas. Can you find out if a role will be good for you even before the world premiere?

WB: Contemporary music is a problem because in the first moment when you start to study the music, you cannot say how good it is, really. There are some things that are overwhelming, yes, but sometimes it’s very difficult to judge if it really great music or not, especially when it’s done for the first time. You have no experience. So it might be that you are caught by the libretto first, the words and what’s going on with the action and the development of the character. Let’s say you work two or three months to learn it, and then you have four weeks of rehearsal. You become very familiar and you don’t have the distance anymore. I did some contemporary operas and they were not good. You found out later because nobody ever asked you to do it again, and they were not given on earth anymore. [Both laugh] But this is not the real judgment. In the contemporary music, with all sophistication and everything there should be enough left that the audience can follow and get something out of it.

BD: Is there a problem in writing music today that we cannot grasp it, or is it that the composers are going too far in a wrong direction?

WB: I think that the composers were going too far in a wrong direction, and I have the feeling it comes back now. When you think of the ’50s and the ’60s, you can hardly call it music anymore. It was just sound. [Sings unmelodiously] So what can you say? You go home and you cannot have a piece of it in your mind anymore. I think there is a way that the contemporary composers feel that they are kind of elite, but nobody’s listening to them anymore. Maybe the sound is too mathematic; it is scientific music. I hear contemporary music now, for example Ligeti, and I love it. It’s beautiful again in a certain way. It’s the not the same beauty as a Mozart or Beethoven had, but it is a beautiful music for me again. But in the ’50s and ’60s, when I hear music I cannot follow that.

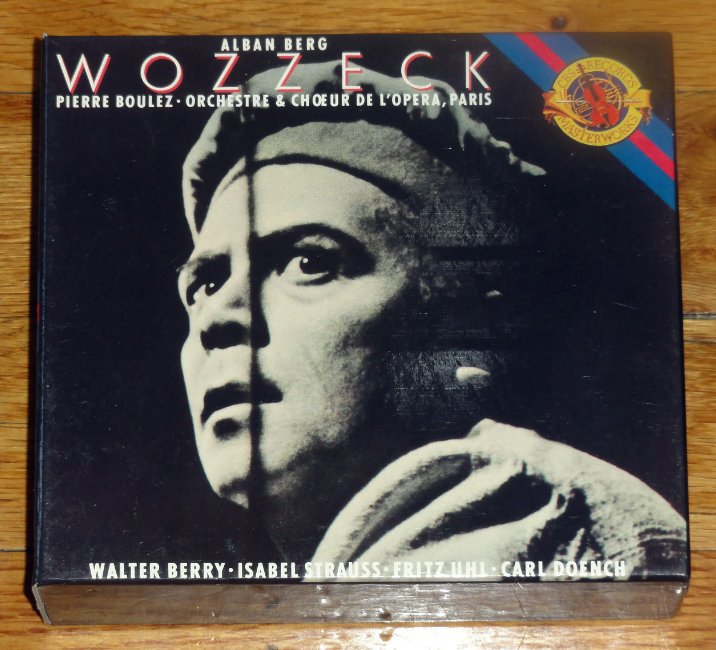

BD: Is Wozzeckbeautiful?

BD: Is Wozzeckbeautiful?

WB: Wozzeck is truly beautiful. I love it! Even when this music is based on mathematics, it’s not always twelve-tone. It is very scientific, sophisticated, mathematic, but it is always dramatic and it has such a beauty. Think of the Zwischenspiel, the interlude before the last scene. This is truly great, beautiful music! It’s completely different from what were used to for music a hundred and two hundred years ago, but it is beautiful. It’s same thing as paintings. Picasso is beautiful, but he has nothing to do with Van Gogh, and Van Gogh has nothing to do with the older masters. It’s a development, but the beauty has to be here. In works that are not beautiful, I really missed anything that touched me. It was just noise to me. I couldn’t follow with my heart! Sometimes a little bit with my brain, but I couldn’t follow with my heart anymore. Now when I hear contemporary music, the new compositions, I can follow with my heart again.

BD: So maybe we’ve come out of the quagmire? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Pierre Boulez.]

WB: I think so. I truly think so.

BD: Good! So you’re optimistic, then, about the future of opera?

WB: Oh, yes! I really am! I know how the audience is in Chicago, in New York, in Vienna, in Rome, and people are going to the opera more and more and they love it. Also I’m speaking about the technical, engineering things that are going on. They shouldn’t be done too well. Even San Francisco is close to Hollywood, but we are not a Hollywood studio. We shouldn’t do an opera in the style of the latest movies.

BD: So the opera shouldn’t try to compete with cinematography?

WB: No. In my opinion I think opera should stay at what it is. We shouldn’t fake technical things. It’s the human being onstage. Who gets the Oscars now in Hollywood but the engineer? Not the actors anymore.

BD: Sure, it’s the technical people.

WB: The technical people. They became very important now. This shouldn’t happen to the opera.

BD: Then how do we get children who go to see the latest movies into the opera house?

WB: This is very much with the education in school hand in hand with what is given at home, because they shouldn’t be caught by what is the action, how big is the explosion, how long the fire lasts. [Laughs] Poor Brünnhilde! They really should be caught by the music.

BD: So then you’re back to recordings again. That’s the way to catch them?

WB: Yes, and they should be very much done in the schools. But if the teachers are not educated already, not being familiar with opera and what we call the “serious” music

— which is not always serious — then how should they know? How should they tell the young people, their pupils, their students, if they don’t know themselves? This is where it goes with the parents and with the school. There should be a little bit more. In Austria we’re so proud — Mozart and Beethoven lived there, Brahms lived there, Bruckner and so on. I always say the education in school is not enough. We shouldn’t sit in a glass house and then leave all of the young people, the young generation, out of that house. You do not have to go anymore in your tuxedo to the opera house. You can go in jeans to the opera house. What’s the difference? If you like to go in the tuxedo, go in your tuxedo. But let the others in with the blue jeans, too.

BD: Tell me about working with Otto Klemperer.

WB: [Even over the phone, one could hear the big smile on his face] Otto Klemperer was a giant! He was looking like a giant and was like a monument already. First of all, he was a very great conductor. I did, as you might know, also Mozart with him. Without disturbing the style, his Mozart became the dimensions of Beethoven. For example, in the last scene of Don Giovanniwhen the Commendatore appears, it is like Beethoven music because it was Klemperer. It was himself. He looked and he acted like the giant. He had this stroke and he had a very strange way to talk, but it didn’t bother him at all. He was in good health, actually; a very strong man! And he had an incredible sarcastic sense of humor. There are, you know, hundreds and thousands anecdotes connected with Otto Klemperer. If I might mention one which shows what I mean with his sarcastic sense of humor... When he had an orchestra rehearsal, the bassoon player didn’t have to play for ten minutes or so. So instead of the music, he had the London Times on his stand. He never thought, back there where he was sitting, that Otto Klemperer could see him, but he saw him. He started the rehearsal and he said, “You at the bassoon! Did you hear what I said?” The man looked up, was shocked at the moment and said, “Yes, yes, Dr. Klemperer, certainly. I heard it. I heard it.” And Dr. Klemperer said, “That’s very strange, because I didn’t say anything.” [Both laugh uproariously] It was typical Otto Klemperer. It just comes into my mind. I love the story very much. After an all-Beethoven program, Klemperer was back in his room and a lady came in. She was so overwhelmed and she had tears in her eyes. She said, “Oh, God, Dr. Klemperer, it was so beautiful, and I’m so overwhelmed. There is no other conductor on Earth who can conduct Beethoven like you.” And Klemperer said, “[matter-of-factly] My dear lady, this is very friendly of you, but you must consider there is also the great... [pauses] there is... [pauses again] there’s... [inhales deeply] you’re right!” [Both laugh again] This was typical Otto Klemperer. We did a recording of Fidelio, and when we had finished the music, Klemperer left and we made all the dialogues. We said, “We want the dialogues a little bit, let’s say, contemporary.” Not too spoken like in the opera house, but more, let’s say, modern. They sent the tape of it to Klemperer, and wherever we had been, we had to come back to London to do all the dialogues again.

WB: [Even over the phone, one could hear the big smile on his face] Otto Klemperer was a giant! He was looking like a giant and was like a monument already. First of all, he was a very great conductor. I did, as you might know, also Mozart with him. Without disturbing the style, his Mozart became the dimensions of Beethoven. For example, in the last scene of Don Giovanniwhen the Commendatore appears, it is like Beethoven music because it was Klemperer. It was himself. He looked and he acted like the giant. He had this stroke and he had a very strange way to talk, but it didn’t bother him at all. He was in good health, actually; a very strong man! And he had an incredible sarcastic sense of humor. There are, you know, hundreds and thousands anecdotes connected with Otto Klemperer. If I might mention one which shows what I mean with his sarcastic sense of humor... When he had an orchestra rehearsal, the bassoon player didn’t have to play for ten minutes or so. So instead of the music, he had the London Times on his stand. He never thought, back there where he was sitting, that Otto Klemperer could see him, but he saw him. He started the rehearsal and he said, “You at the bassoon! Did you hear what I said?” The man looked up, was shocked at the moment and said, “Yes, yes, Dr. Klemperer, certainly. I heard it. I heard it.” And Dr. Klemperer said, “That’s very strange, because I didn’t say anything.” [Both laugh uproariously] It was typical Otto Klemperer. It just comes into my mind. I love the story very much. After an all-Beethoven program, Klemperer was back in his room and a lady came in. She was so overwhelmed and she had tears in her eyes. She said, “Oh, God, Dr. Klemperer, it was so beautiful, and I’m so overwhelmed. There is no other conductor on Earth who can conduct Beethoven like you.” And Klemperer said, “[matter-of-factly] My dear lady, this is very friendly of you, but you must consider there is also the great... [pauses] there is... [pauses again] there’s... [inhales deeply] you’re right!” [Both laugh again] This was typical Otto Klemperer. We did a recording of Fidelio, and when we had finished the music, Klemperer left and we made all the dialogues. We said, “We want the dialogues a little bit, let’s say, contemporary.” Not too spoken like in the opera house, but more, let’s say, modern. They sent the tape of it to Klemperer, and wherever we had been, we had to come back to London to do all the dialogues again.

BD: He did not approve?

WB: He did not like it at all! He said, “This is much too modern. It doesn’t fit with the way I am doing the music, and you have to do it again.” When I came onstage as Pizarro and I said [speaks some lines extremely fast in a rapid-fire style], he didn’t like that at all! He said, “No, you have to say it in the same tempo the aria’s going on, [Speaks the same lines at a much slower pace].” We didn’t like it at all, and we thought, “Oh, my God, that old story again,” but in the end he was right. It melded together much better.

BD: Weren

’t there some recordings of other works where the singers did the arias and another cast of actors did the dialogue?

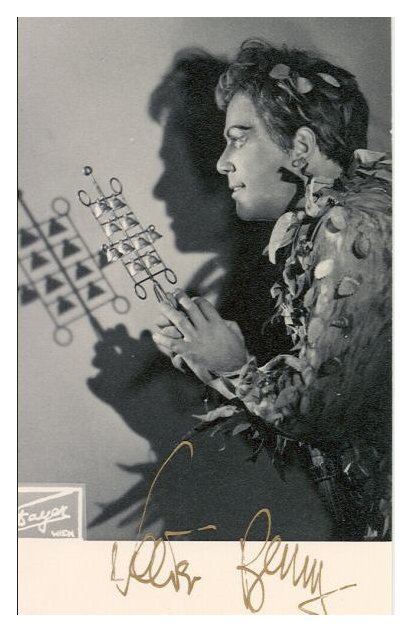

WB: I cannot recall one recording I haven’t done the dialogue myself. When I sang Papageno, which I don’t do anymore, I wouldn’t like it if somebody else would do the dialogue. Because, like Klemperer wanted the dialogue melding into his interpretation of the music, my dialogue is coming from what I was singing before and what I’m singing after. For me, it would break the line.

BD: There’s no dialogue, though, in the Klemperer Magic Flute.

WB: No. Not in the Klemperer. I did another one with Sawallisch. The Sawallisch one is with the dialogue, but Klemperer didn’t want it. After the (Klemperer) recording, we did it in concert in the Royal Festival Hall in London, and we also did it without any dialogue. Papageno sings his little song three times, and before that third verse he wanted me to say, in the concert version where nobody else was speaking, “And now, with variations.” I thought, “No, I don’t like it.” What will the audience think when all of a sudden I start to talk to them? I thought he might have forgotten it, so we made the first verse and we made the second verse, and he didn’t go on. He looks at me and I looked aside. I didn’t look at him. Then very loud and clear he said, “And now! And now!” So I said, “And now, with variations.” [Laughs] So this was the only dialogue we did in this concert version.

BD: Let us move to another character, Baron Ochs.

WB: Mmmm... Difficult. He’s a relative to Falstaff a little bit but not as intelligent as Falstaff is. The problem always is that he’s not nice at all. What he says, the way he acts is not nice at all. What the Marschallin says about him is not nice at all, but the audience must love him.

BD: He has to be a loveable rascal?

BD: He has to be a loveable rascal?

WB: Yes! [Laughs] I had a problem with that all the time because you cannot be always nice, but he is not nice at all. He’s just looking for the money. He wants that young girl. He’s kind of a dirty old man, but the audience needs to like him. At the same thing is going on in the opera, Strauss has made the waltz to Baron Ochs, which didn’t exist at that time the opera plays in. So you see, there is, as I say, a break in the line.

BD: It’s a little license.

WB: Yes. But the more you are it and the less you do, the better you are as Ochs. The less you “act” Ochs, the more you really are. There are some parts you have to be, like Carmen and like Baron Ochs and like Don Giovanni. The best singer could sing everything else, but it might just be that she’s not a good Carmen. There is a certain thing and you have to have it. It’s the same thing with Don Giovanni. You can take wonderful baritones, and I’ve done it with a lot of wonderful singers. They were excellent in other parts but they were not as good as Don Giovanni. Because I admire him so much I can mention the name

— Hans Hotter was such a wonderful singer! However, he was never a very good Don Giovanni. He was wonderful in Wagner. But Cesare Siepi? He has it. He is a Don Giovanni. For some reason, he goes onstage and everybody believes in him. This is also a very difficult part. Don Giovanni is at the end of his career as a seducer. He can’t even seduce that stupid Zerlina anymore!

BD: No, he doesn’t get anybody, actually, in the opera.

WB: Nobody. He’s at the end of his rope! But the audience must love him and must believe that he’s a symbol.

BD: Does Baron Ochs try to be a Don Giovanni?

WB: No, but maybe in a very awkward, humble way. Of course he wants to be. He has known who Don Giovanni was because Don Giovanni was there for eternity, and to be like Don Giovanni was always in the macho behavior.

BD: Let me ask about one other part, Barak.

WB: Barak is really something I cannot say very much about it because I’ve been so close to Barak that I cannot even think of what I am doing.

BD: Is he the character that is closest to Walter Berry, then?

WB: Somehow maybe yes. I’m ashamed to talk too much about it. I would give too much away of myself. But really, Barak I don’t have to act. I feel it so much with the music and with the part. I cannot say very much about him because I really feel it so much.

BD: Let me ask about Herbert von Karajan. You’ve worked a bit with him.

WB: Yes. I’ve worked a lot with Herbert von Karajan, and it has always two sides. On the one side he can carry you in his hands with the orchestra. He knows so very much about music and he can make music sound so beautiful. It’s incredible and you can learn so much, because when you watch him at an orchestra rehearsal, for example, he will let them play for ten minutes and then he picks out two or three bars and he makes those two or three bars trademark Karajan. He’s one of the few conductors I can recognize when I hear the record played in the radio and I didn’t hear the announcement. It’s so special.

BD: Are his productions more unified because he is both producer and conductor?

WB: This is a difficult question. It is as difficult as Herbert von Karajan is as the man himself. I can understand him and what he wants in his ideas onstage, but I don’t know if he really is able to judge if those ideas he has about the staging really are fitting to his music so well. If he could find, in his opinion, a congenial partner, maybe there would have even been better results.

BD: I just wonder if there’s any producer in the world who could get along with him and work with him on his level.

WB: Yes, he’s incredibly demanding. He’s very much demanding, actually, but there are a few producers I know that have worked very well with him. Ponnelle has worked with Karajan. Oscar Fritz Schuh has done Don Giovanni I think back in the early ’60s. Teo Otto made the sets, and Oscar Fritz Schuh was the director; Karajan was just conducting, and in my memory it was one of the most exciting Don Giovanni’s I have ever seen. Karajan was satisfied and happy, but maybe later on he didn’t find the right partner. I don’t know. He had the obsession that he had to do everything himself. I mean that with all respect. I’m not saying that I don’t like it... even I don’t like it all the time! But I don’t know if it wouldn’t be a stimulation, you know what I mean? To have something you can talk about with him, then talk to yourself always. I’m sorry I cannot express myself better in English, but I hope you know what I mean.

BD: I think so. It’s having to work with yourself and not getting the stimulation from other input.

WB: Yes, and you know how much comes out if you talk about things. To whom shall he talk when he does everything?

BD: He has to talk to a mirror.

WB: Yes! Yes, but the mirror’s not the right partner, especially when you become older!

BD: You enjoy singing, don’t you?

WB: I enjoy singing. I’m always aware that it’s very much demanding from yourself, from your life, from your lifestyle. It is something I feel devoted and responsible to when I do it. I’m just a human being, but I really try every evening. I’m the type of a singer that tries to do as much as I can for my audience every evening, and if I don’t do so, I am not satisfied myself. Human nature is so, what shall I do? And when you develop a cold, you have to go on. There is nobody else. Then you are just seventy percent, but then I give that seventy percent as much as I can.

BD: That’s a wonderful way to sing, and a wonderful way to live your life.

WB: Yes, I think so. When I look back and when I look to what I’m doing now, I must say I have done with my life and do with my life the best I can.

BD: You’ve left a wonderful legacy of performances and recordings, and I really appreciate your taking the time in the midst of this busy Ring cycle to chat with me.

WB: There are just two more left over now and then I’m through. In about fourteen or fifteen days, I have made nine performances, and just keep in mind how many rehearsals we had in six weeks for three different operas. It was a lot of work, but it was really worth it.

BD: Will you be back in Chicago?

WB: Not so far. I had an invitation for a part. I don’t mention what it was, because of my colleague who is doing it. I was thinking very much about it. It would be new in my repertory, and then I said no because I thought I am not the right person for this part. So for this I’m not coming to Chicago, but I truly hope to come there, because I love it.

Thank you very much for calling, Bruce, and I want to say hello to all my friends in Chicago. They remember me.

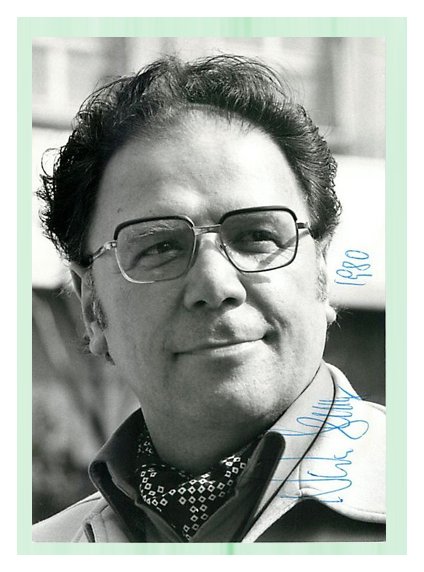

Walter Berry

His mellifluous bass-baritone voice delighted opera audiences

By Alan Blyth, The Guardian, Sunday 29 October 2000 [Text only - photos added for this website presentation]

For an appreciable number of years, the role of Papageno at the Vienna State Opera was synonymous with the name of Walter Berry, who has died aged 71. His reading of the role became indelibly imprinted on the mind of audiences, and not only in the Austrian capital; he sang it throughout the German-speaking world and beyond, though, sadly, never in London, where his talents were unaccountably neglected throughout a career of more than 40 years on the operatic stage.

When he was belatedly called to Covent Garden, as late as in 1976, it was as Barak, the plain man personified, in Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten, a deeply-felt and moving portrayal in which he deployed his rich and mellifluous bass-baritone voice to notable effect, seconding his vocal attributes with the appropriate body language.

In 1986, he returned in a very different Straussian part, that of the impecunious, rascally Count Waldner, in Arabella. The voice of a singer by then well into his 50s seemed hardly affected by the passing years, and, quite recently, he was heard on disc in the tiny, but important, part of the Major Domo to Renée Fleming's Countess Madeleine, in the final scene of Strauss's Cappriccio. Berry brought significance to his phrases, as he had done throughout his lengthy career.

That began while he was still a student at the Vienna Music Academy in 1947 (studying with several notable teachers), when he made his stage debut singing Simone in Gianni Schicchi, Falstaff in Nicolai's The Merry Wives Of Windsor, and van Bett in Lortzing's Zar und Zimmermann.

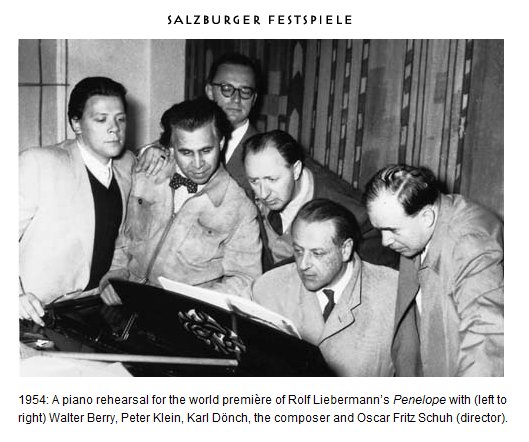

Photos of those productions show the young Berry as obviously a singing-actor of great promise. That was fulfilled when he gained a contract at the Vienna State Opera in 1950, remaining with that ensemble for the rest of his professional life, while commuting in the summer to the Salzburg festival, where he sang regularly from 1952 onwards, creating several roles in operatic premieres.

Although he first undertook small roles in Vienna - such as Silvano in_Un ballo in maschera_ - he was soon promoted to Masetto in Don Giovanni, and then to Papegeno and Figaro, which became his calling-card in other houses. He was also a noted Guglielmo, later Don Alfonso, in Così fan tutte, singing the latter role in Karl Bohm's classic 1962 recording for EMI. His first appearances on stage in London took place during the visit of the Vienna State Opera to the Festival Hall in 1954, when he appeared as Figaro and Masetto.

As the years went by, Berry's voice grew in strength and range, and he began to tackle more dramatic repertory. His assumption of the title part in Berg's Wozzeck was one of the summits of his achievement, the downtrodden soldier to the life, but he was also admired, among many other parts, as Amonasro (Aïda), Jochanaan (Salome), the four villains in Offenbach's The Tales Of Hoffmann, Cardinal Morone, in Pfitzner's Palestrina, and, eventually, Wotan, in Die Walküre, one of his roles at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, where he made his debut in 1966 as Barak.

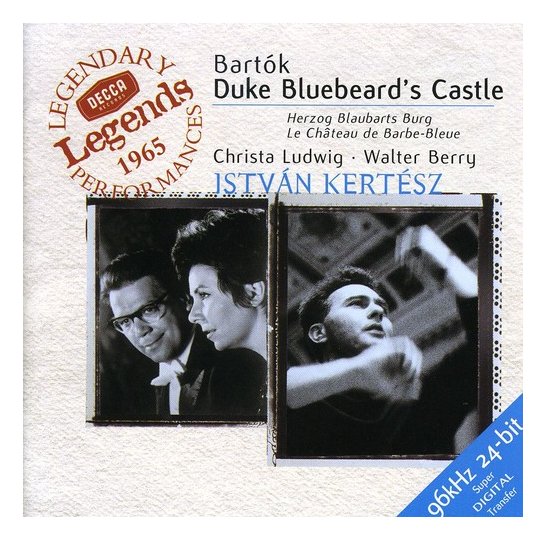

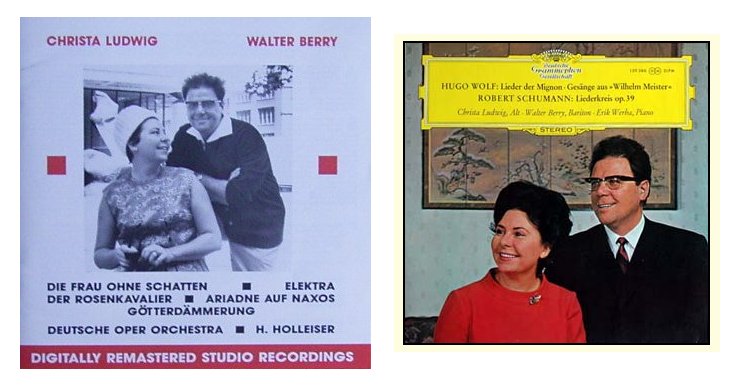

Another of Berry's specialities was the title role in Bartok's Duke Bluebeard's Castle; his recording of that part, with his then-wife, mezzo Christa Ludwig, and conducted by Istvan Kertész, is still considered one of the best renderings of the opera on disc. This was one of the many examples where Berry subsumed his genial presence in the cause of enacting an unsympathetic part.

Berry and Ludwig married in 1956 and divorced in 1971. While they were a pair, they frequently appeared together on stage and in concert. Berry's truly Viennese Baron Ochs, to Ludwig's authoritative Marschallin, was a partnership worth catching in the 1960s in Vienna. It is preserved on record in the set conducted by Leonard Bernstein, who also accompanied the couple in the piano-version of Mahler's Knaben Wunderhorn cycle.

Berry was an accomplished interpreter of lieder, and a noted soloist in many choral works. He also enjoyed letting down his hair in operetta, especially as Dr Falke, in Die Fledermaus. In everything, his innate musicality was always in evidence. Nothing in his performances was exaggerated; everything emerged from the given text. Nor did he ever extend his talents beyond their natural limits, which probably accounts for the fact that his career lasted so long.

He is survived by his son.

• Walter Berry, opera singer, born April 8 1929; died October 27 2000

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded on the telephone on June 14, 1985. Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB the following month, and in 1989, 1994, 1998 and 1999. It was transcribed posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.