Dawn Upshaw Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Soprano Dawn Upshaw

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

It says much about Dawn Upshaw’s sensibilities as an artist and colleague that she is a favored partner of many leading musicians, including Richard Goode, Kronos Quartet, James Levine, and Esa-Pekka Salonen. In her work as a recitalist, and particularly in her work with composers, Upshaw has become a generative force in concert music, having premiered more than 25 works in the past decade.

From Carnegie Hall to large and small venues throughout the world she regularly presents specially designed programs composed of lieder, unusual contemporary works in many languages, and folk and popular music. She furthers this work in master classes and workshops with young singers at major music festivals, conservatories, and liberal arts colleges. She is Artistic Director of the Vocal Arts Program at the Bard College Conservatory of Music, and a faculty member of the Tanglewood Music Center.

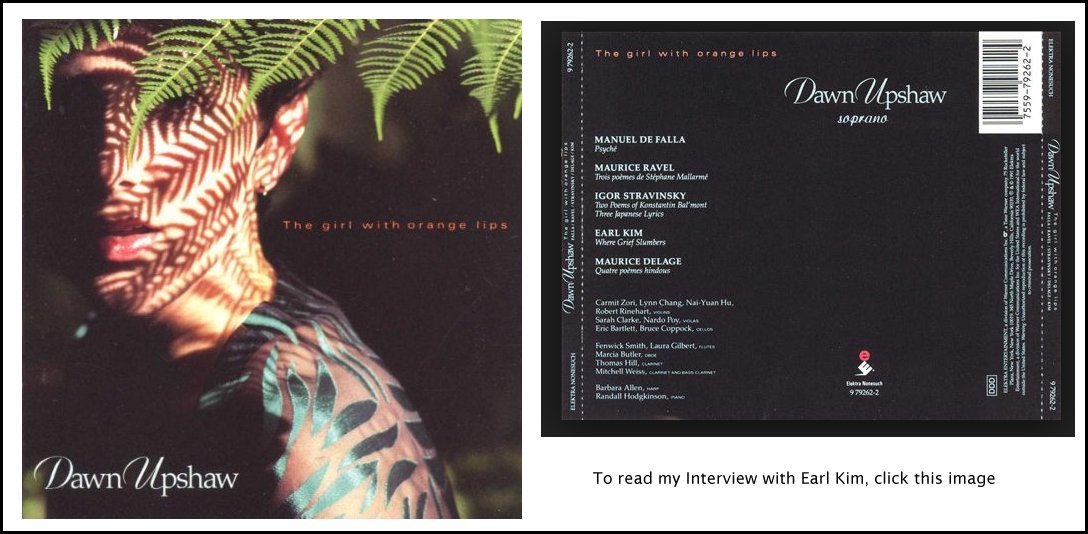

A four-time Grammy Award winner, Dawn Upshaw is featured on more than 50 recordings, including the million-selling Symphony No. 3 by Henryk Górecki. Her discography also includes full-length opera recordings of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro; Messiaen’s St. Francoise d’Assise; Stravinsky’sThe Rake’s Progress; John Adams’s El Niño; two volumes of Canteloube’sSongs of the Auvergne, and several music theater discs and a dozen recital recordings on Nonesuch.

Dawn Upshaw holds honorary doctorate degrees from Yale, the Manhattan School of Music, Allegheny College, and Illinois Wesleyan University. She began her career as a 1984 winner of the Young Concert Artists Auditions and the 1985 Walter W. Naumburg Competition, and was a member of the Metropolitan Opera Young Artists Development Program.

-- From the Nonesuch Records website.

-- Throughout this page, names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

My old college roommate

— a timpanist who eventually edited the school newspaper — knew Upshaw from his alumni connections, and when she was in Chicago in April of 1991 we arranged to meet at his downtown office. It took a couple of minutes to get things set up to tape a radio interview, and I tried to make sure that my guest was comfortable before we started chatting . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Do you have to be comfortable to sing?

Dawn Upshaw: Well, goodness knows, I have sung feeling quite uncomfortable. Whether that’s just from nerves, or being in a strange position, I don’t know! [Laughs]

BD: It’s often the case that the designers will have these outlandish costumes, and the stage design will be very raked.

BD: It’s often the case that the designers will have these outlandish costumes, and the stage design will be very raked.

DU: Yes. I suppose there are many different ways that you can be distracted and uncomfortable.

BD: How much pure concentration do you have to have every night when you’re onstage, whether it be in opera or recital? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, also see my interview with Roger Norrington._]

DU: That’s a difficult question to answer. I don’t know where you draw the line, but you have to be able to keep your concentration so that you aren’t distracted by too many things. I can only take a few people walking in and out of a concert before I lose my concentration. Hopefully, that doesn’t happen more than once a year!

BD: In the opera you’ve got people walking around backstage, and you’ve got the prompters screaming at you and the conductor waving the stick, and all the orchestra players that you can vaguely see...

DU: Yes, but that doesn’t bother me, really. You become accustomed to the idea that once you get out onstage it’s another world, and at least wherever I’ve been, the conductors are not right in front of you.

BD: They’re thirty miles away?

DU: Yes, unfortunately they’re a little far sometimes.

BD: When you walk out onto the stage, is this the world of the libretto, or is this the world of the opera house, or is it still the world of Dawn Upshaw?

DU: I would hope that it’s a true, equal combination of the libretto and music and a bit of me put in there. But that can’t be helped. I have to face the fact that it’s me performing, so a lot of me is going to come out. But that’s not my concentration, hopefully.

BD: Do you put your stamp on each role that you sing?

DU: I don’t think of it that way. I try to find out what the role is about, and find out what the composer might have intended by writing it any particular way. I don’t think about trying to impress people with Dawn Upshaw, but maybe I try to impress them with the music. That sounds awfully goody two-shoes, but I really do think that there’s enough in the role to keep an audience interested without trying to put your own stamp on it.

BD: Your voice dictates which roles you will sing. Do you like the characters that are imposed on your voice?

DU: For the most part. Some people may notice that I don’t sing much Donizetti and Bellini and Rossini, and one reason is because I don’t feel as strong a connection with those characters and those personalities as I do with some of the Mozart roles; although I certainly have some trouble with some Mozart, too. I may get to some of that other Italian music at some point, but right now I’ve decided to put it aside. It just doesn’t feel like a part of me at the moment.BD: Tell me the secret of singing Mozart!

DU: For the most part. Some people may notice that I don’t sing much Donizetti and Bellini and Rossini, and one reason is because I don’t feel as strong a connection with those characters and those personalities as I do with some of the Mozart roles; although I certainly have some trouble with some Mozart, too. I may get to some of that other Italian music at some point, but right now I’ve decided to put it aside. It just doesn’t feel like a part of me at the moment.BD: Tell me the secret of singing Mozart!

DU: The secret! [Laughs] Yes, a wonderful question! I don’t have the secret to singing Mozart. Mozart has been a great inspiration and a great teacher for me. Every time I get to a Mozart score, I learn a lot about myself and I learn a lot about my singing and what needs work. You can’t hide behind any of Mozart’s music. In some ways it’s all very simple, and in some ways it

’s the most complicated music that I’ll probably ever sing. Even though I’ve sung a lot of Mozart,I don’t think of myself as any kind of Mozart specialist because, in a sense, I feel I have just begun in this career. It just so happens that there’s been a lot of Mozart to sing because of the bicentennial celebrations. So I wouldn’t even consider calling myself a specialist.

BD: You’re the right voice at the right place at the right time, and then you’ll move on?

DU: Yes. I imagine I will continue to sing Mozart, but I’m interested in getting into some other things

— like some Richard Strauss, maybe Sophie in Rosenkavalier or even Zdenka in Arabella. I would like to try that role, and some Stravinsky.BD: Zdenka is one of the few times you could play a girl playing a boy.

DU: That’s right. [Laughs]

BD: It usually goes to the mezzo soprano.

DU: Yes, right.

BD: You’ve recorded now a couple of the big Mozart roles

— Susanna in Marriage of Figaro, and also Celia inLucio Silla. Tell me about the Lucio Silla since we don’t know as much about that one.

DU: Lucio Silla is a very early Mozart opera. I think he was seventeen when he wrote it. It

’s an opera seria with many, many arias, not very many ensembles, and is a bit static dramatically. This was a recording with Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Concentus musicus in Vienna.

BD: Is it a role you would ever do onstage?

DU: Possibly. I don’t think it would be all that interesting onstage. Someone could tackle this opera and make a wonderful production out of it, but whether an opera company is willing to give it a try? It’s probably been done, or is even being done this season, with the Mozart celebrations, but it would have some difficulties onstage.

BD: Is it good that we go beyond just the big three or four Mozarts, and explore some of his lesser-known operas?

BD: Is it good that we go beyond just the big three or four Mozarts, and explore some of his lesser-known operas?

DU: Oh, sure. There’s some incredible music in this opera, even though it may be a bit static dramatically. It’s amazing to see what he was writing at such an early age. It’s fascinating. It still has great strength.

BD: Because it’s so static, perhaps it works better as a concert or as a recording?

DU: I suppose, although I would even have some trouble sitting down and listening to it all in one session. I’d probably want to break it up. In a concert it’s probably a little bit easier because you have the added visual. Even though it’s in concert you get to watch the singers, and I think that still adds something to a performance that you don’t get when you’re just listening to a recording.

BD: You are also in a recording of Chérubin, about a different Cherubino. Tell me about the Massenet work.

DU: It’s another story about Cherubino, but it’s not Beaumarchais. It’s a new libretto, and kind of a static, weird story, which is why it probably hasn’t been done very much onstage. It has some beautiful music — in fact I think my role gets the most gorgeous music in that opera. I sing the part of Nina, and it’s very similar to Sophie in Werther. It’s the same sort of range and somewhat the same character, but she’s a little bit older than Sophie and a little bit more knowing. It’s a wonderful part for Frederica von Stade. She does a wonderful job with Cherubino, as she has with that character for a long time.

BD: You’ve done a lot of singing at the Met, where they don’t use supertitles. Have you sung elsewhere where they do use supertitles?

DU: I have sung just twice with supertitles

— once several years ago on tour with the Met in Japan they used supertitles for Figaro, and there was another Figaro performance that I did a few years ago at the Wolf Trap Festival.

BD: Do you like the use of supertitles?

DU: I have mixed feelings about it, and I’m not just saying that to ride the fence and be on everyone’s good side about it. For a long time I was really against it because I felt that it would be very distracting, and I still have trouble with that myself. When I’ve gone to an opera and they’ve used supertitles, I’ve found that I was watching the supertitles more than I was watching what was going on onstage. At the same time, there’s so many people who don’t speak the languages that are being sung, and that’s a big problem. You miss out a lot if you don’t understand what’s being said, not only word for word but just having an understanding of what’s being said sentence to sentence. This brings us to another idea, and that is of translating things and singing them in the vernacular, singing them in our own language, in English. Again, I have mixed feelings about that. It would be wonderful for everyone to understand nearly every word that was spoken. At the same time, there’s something to be said about the poetic beauty of an opera in its original language. The composer may be choosing to write a melismatic phrase or something on a more easily sung vowel, so it gets very complicated.

BD: We just have to get Andrew Porter translations for everything!

BD: We just have to get Andrew Porter translations for everything!

DU: Yes. He does a nice job.

BD: It’s a trade-off, and obviously you gain something and you lose something from each of these new techniques, so you have to decide what you want the audience to get.

DU: Yes, right.

BD: Where’s the balance, then, between the music and the drama in opera? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, also see my interview with David Zinman._]

DU: I sure would like to see a little bit more of the drama onstage. It’s better than it used to be.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean, you don’t want to just stand and sing???

DU: [Laughs] No. I hope I don’t do that. It’s an interesting art form, and if you don’t take advantage of the fact that there is something going on dramatically, you really lose out on the wonderful aspect of the art form of opera. Where else do you get the combination of all of those things going on at the same time?

BD: And hopefully, all in a good balance.

DU: Yes.

BD: Well, who should be the strong man

— the conductor in the pit, or the stage director?

DU: I would really like to see an equal collaboration, not only between the conductor and the stage director, but also the designer and the singers. I don’t think the chances of this happening any time soon are very good. We’ve been through lots of different phases of who is most important, and I just think that it would be healthiest, and probably best for the music and the operas themselves if everybody had an equal part. It seems to make sense to me, but I don’t think the powers that be will listen to me for a long time! [Laughs]

BD: I would assume, though, that most productions you aim for that, and get as close as you can?

DU: One would hope so.

BD: Or am I just a naïve listener?

DU: Everybody has an idea of what’s most important in the opera. I don’t think that there are all that many conductors and directors that are just as interested in what the singer wants to do as what they themselves want to do with the piece... and perhaps for good reason. Maybe there are some singers who don’t bother to involve themselves as much as they could, but for the most part everybody could be a little bit more open-minded and consider the ideas of others.

BD: We were talking earlier about various roles. How do you decide which roles you’ll accept, and which roles you’ll turn down? DU: I make a decision about whether I think that they’re appropriate for me right now.

DU: I make a decision about whether I think that they’re appropriate for me right now.

BD: What is appropriate for you?

DU: There’s no clear answer to that question. I take a look at the range and at the demands and the tessitura and the character. I do the same thing for songs, too. If I’m not sure of something, I have people in the business whose opinions I respect, and I can go and ask them to give me some help. But I’m in no big hurry, so I’ve turned down a few things that I felt were definitely too much for me right now.

BD: But you might come back to them five or ten years down the line? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, also see my interview with James Levine._]

DU: Maybe.

BD: Does it surprise you when someone comes to you and suggests

— or even offers you a contract for — a role that you think is outlandish?

DU: Yes, but unfortunately, I just lose respect a little bit for whoever asks me that, and I learn not to trust their judgment perhaps as much as I would have otherwise, in terms of what they think I ought to do. I was very surprised by a very well-known conductor who thought I should be singing Mimì. This was someone I had really hoped to work with, and I was just amazed that he could be so wrong about what was best for me right now. At least that saved me from feeling too bad about the fact that I haven’t worked with him because maybe we wouldn’t have been the best matched-up pair. [Laughs]

BD: How do you divide your career between opera and concerts?

DU: Luckily, I started out on the concert end of things. Opera came a bit late for me. I had done very little in college and in graduate school, and once I became part of the Metropolitan Opera Young Artists program, then I became much more interested, and got more work in opera. But I still manage to perform maybe fifteen to twenty recitals a year.

BD: Is this what you originally wanted to be

— a recital singer?

DU: Yes, that was my first love, and for a while my only love. So I’ve always wanted to continue that, and chamber music, and so far it’s been a really nice combination of recital and opera. Operas are scheduled really, really far in advance, at least the big opera houses, so I end up trying to save a fair amount of time in my schedule for concert and recital work.

BD: If you wanted to be a recital singer, why did you accept the position with the Young Artists program at the Met?

DU: Because I wanted to find out a little bit more about what was involved in the opera world. I had had a little taste of opera and knew that I liked it. It’s just that I was most familiar with preparing songs rather than preparing arias. I was definitely sold shortly after I was in the program, and knew that I wanted to sing opera.

BD: How is it different to prepare a song than to prepare an aria?

DU: It’s not any different.

BD: [Surprised] None at all???

DU: No. I don’t think it should be any different. The only difference is perhaps being onstage and what you possibly will be able to achieve there. With just the so-called accompaniment of piano in a recital and not a full orchestra, perhaps there are more colors you can choose from. It’s also a more intimate setting than a large opera house. But in terms of preparing how I would sing something technically, or how I would interpret it, there’s no difference.

DU: No. I don’t think it should be any different. The only difference is perhaps being onstage and what you possibly will be able to achieve there. With just the so-called accompaniment of piano in a recital and not a full orchestra, perhaps there are more colors you can choose from. It’s also a more intimate setting than a large opera house. But in terms of preparing how I would sing something technically, or how I would interpret it, there’s no difference.

BD: So you can find a lot of drama even through a very short song?

DU: Oh, yes. There’s often much more drama packed into a song than there is in an opera. The ideas take a much shorter amount of time in a song than the same amount of time in an opera. Most often that’s the case because the opera is spread out over such a long period, and often there’s not nearly as much happening dramatically as there is in a little song.

BD: Is each song a little opera, or at least full scene?

DU: Sometimes. Mozart’s “Das Veilchen,” that song about the little violet, is like a little opera. It’s very dramatic!

BD: When you’re singing the songs, I assume you want the audience to be following along the text?

DU: I would like for the audience to come maybe a little bit early to the concert and read through the poems, try to get a taste for what the poetry is like, what words were chosen and maybe enjoy the flavor of the poetry, if possible, which is hard to do in a printed translation. But ideally I would like for them to watch me the whole time in performance, and not have their heads lost in their translations. There’s a lot to be gained — hopefully [laughs] — by watching my performance, if I’m doing a good job.

BD: You bring a lot of expression to your face and to your hands?

DU: Yes. I hope to, yes.

BD: Do you adjust your technique at all for a small house or a large house?

DU: Not really. It’s more like being able to take more risks in a smaller, more intimate setting, than the risks I could take with an orchestra in a large house.

BD: Do you do all of your work and all your preparation in the rehearsal, or do you leave a little bit of spark for that night when you and the pianist are onstage?

DU: [Laughs] I don’t think that one should assume that just because one might rehearse a lot that there wouldn’t be any spark left. With good performers, hopefully there’s always some kind of improvisation and spontaneity in a performance. I enjoy most working with pianists that feel that freedom themselves, and then give me that freedom to live in the moment.

BD: You’ve made a number of recordings. Do you sing the same in the recording studio as you do in the concert hall?

DU: I hope so, because a recording should be listened to and thought of as another performance. I get upset when people want recordings to be perfect, because I don’t think that any performance is perfect. I don’t think that’s what people really want. People want to be moved by music. They want to go home with something, having learned something, having experienced something or felt something that they didn’t feel before, and those same things should come through on a recording. Sometimes that’s even harder to do on a recording because you don’t have the chance to watch the artist, whether it’s the singer or a pianist or other instrumentalist. That vision adds a lot to a musical experience. You can say, “I enjoy most just sitting back and closing my eyes.” I enjoy doing that myself sometimes, but it means a lot to see how someone might move while they’re working, while they’re playing. In any case, I hope that my recordings will have as much conviction and love for the music as I hope my performances have. Whenever I get upset because something’s not absolutely perfect on a recording it takes me a while to get over it, but I usually convince myself that’s not what’s most important.

BD: Are you basically pleased, though, with the recordings that have come out thusfar?

BD: Are you basically pleased, though, with the recordings that have come out thusfar?

DU: Basically. I always want things to be better, so it’s difficult. It’s probably difficult for anybody to watch themselves in a home movie or listen to themselves on their tape recorders. It’s hard to listen to myself on a recording.

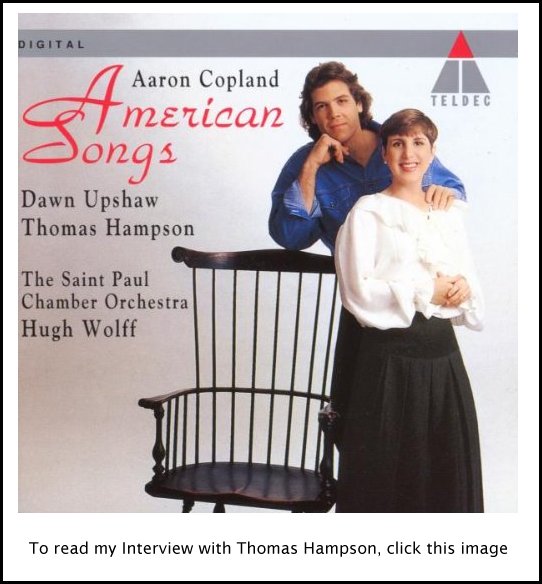

BD: Yet you’re not the best judge of your performance, really. [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, also see my interview with Hugh Wolff._]

DU: No, but in a sense I’m going to be the hardest on my performance than anybody else, harder than anyone I can think of. I’ll be much more judgmental.

BD: You’ve recorded some American music. Are you a big proponent of American composers and American songs?

DU: It’s important to seek out or enjoy the music of my time, the music of my country. I don’t think that it’s unusual; I don’t think it ought to be unusual. It might be unusual, but I don’t think it ought to be unusual. I’m not trying to wave this banner and make a point with it at all; it’s just something I enjoy. I love singing in English. A lot happens when I sing in English that probably doesn’t happen when I sing in other languages. I learn a lot by singing in English because I realize I do even more with the words. I create even more variety of sound and of images. I’ve tried to bring this into my work in other languages, because I realized a while ago that I had this stronger connection and stronger conviction about music that I was singing in my own language.

BD: In each recital do you try to include a group of American songs?

DU: No, not always. I often do, and although I still continue to do kind of the hodgepodge type of recital program, I’m more and more interested in bringing all these pieces together in some sort of common denominator, having some sort of theme. That’s a little more interesting, and there’s a lot of music that is sent to me from composers. I love looking at new things, and often will come across something that I want to include at some point, that I want to perform. But I don’t make a point to save a little group for the American folks. [Laughs]

BD: Do you have any advice for someone who wants to write songs for your voice, or indeed, any voice?

DU: If you’re interested in writing for a particular person, of course it would help to hear them perform several times beforehand, and probably talk with them about what might be a most comfortable range, or what poetry they might be interested in if you want to include them in that aspect of your composition. Periodically, while you’re writing the piece, it’s good to work with the singer and make sure that they’re comfortable with it, or that they understand and can conceive of what you have in mind while you’re writing.

BD: What advice do you have for younger singers coming along, if any?

DU: My advice has been, and still is, to just get out and sing in front of people as much as possible, because even if it’s for a very small group of friends, or auditioning for competition that maybe you might not think is worthwhile. Use any opportunity to sing for people. I learned early on that I had to discover who I was as a performer, and what was important to me, and I couldn’t really do that all the time in the practice room. It changed when I got in front of people. I became nervous, or I began worrying about what others thought. It’s important to gain confidence in yourself, and to discover what you’re all about as a musician.

BD: Do you like being a wandering minstrel?

DU: [Laughs] I’m not crazy about that aspect of this career! It makes for a very interesting life for a while, anyway, all the traveling and going to a lot of interesting cities and interesting countries. But I look forward to settling down a little bit more in a few years. I want to continue performing, but perhaps not with such a rigorous schedule as the one I have now.

BD: Are audiences different from city to city, and country to country?

DU: Yes, sure. In fact, sometimes I perform someplace where the presenters ask me to do something in particular, because that’s what their audience is used to, or not to do something else, because they’re not used to it. Sometimes I adhere to those requests, and sometimes I don’t. I’ve been asked to sing arias in song recitals, which I have refused to do. I have real qualms with that whole thing, but we won’t get into that now. [Laughs]

BD: You don

’t like reducing the orchestra into the piano?

DU: Right. I’m not crazy about it, but that’s not the main problem. I just feel like the song recital is having enough trouble in this country, in particular, selling, and part of that problem is that we’ve got some really huge halls. It’s mostly about money, as are most of the problems in this world, but we have huge halls that presenters need to fill, so they try to bring in really well-known opera singers, and the audiences that are attracted are opera audiences, and they want to hear arias. They call it a song recital, but half of the program is arias from operas, and I think this does real damage to the art form of the song recital. Many, many, many of the composers who wrote operas also wrote songs, so they certainly knew the difference between the opera stage and the chamber hall, or chamber room

— someone’s living room, which many of these things were written for. So I hope that we can save the recital in this country. This problem does not exist very much in Europe, frankly.

BD: They have a big tradition of it.

DU: Right, and that’s another problem. We don’t have a tradition here of the song recital in our own language like the Germans do or the French do. A German singer will sing an entire program of German songs, or a French singer an entire program of French songs. I frankly see no problem with singing an entire program of American songs, but the people who come to song recitals know about the German and French and English traditions, so they are used to hearing a bit of this and that. That’s why there’s a big difference here in this country.

BD: Is the song recital really a viable medium here in America, as we head into the last decade of this century?

DU: Perhaps not in the shape that it’s in right now. There’s actually a competition now in New York, the Chloë

Owen Competition. The prize, along with some money, is a recital in New York City, and you must prepare an entire program of music from living composers with American citizenship. That is the requirement, and it’s been a big hit. They’re in their second year now, and the first year and the concert itself was all very well received. Maybe there’ll be some changes, and maybe people will be more and more interested in a full program of American music.

Chloë Owen (Soprano)

Born: December 21, 1918 - Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

Born: December 21, 1918 - Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

Died: April 28, 2010 - New York City, New York, USA

The American soprano and music pedagogue, Chloë Owen was born into a musical family. After early musical training and graduate work at the Peabody Conservatory, Chloë arrived in New York City, where her Town Hall recital in 1951 received critical acclaim. Under Columbia Artists Management, Chloë Owen toured with Community Concerts nationally before embarking for Europe. There, her study with Hans Hotter, Germaine Lubin, and Giuseppe Pais led her to a warmly remembered opera, oratorio, concert and radio career of 19 years, almost exclusively European.

Owen’s extraordinary range and vocal prowess allowed her to perform roles as diverse as the Queen of the Night in Die Zauberflöte, Micaëla inCarmen, and Elsa in Lohengrin. She sang in the Salzburg Festival world premier of Irische Legendeby Werner Egk, conducted by George Szell. American and European critics alike noted her artistry and passionate commitment to serving the intention of both composer and librettist, with her range, flexibility, stage presence, and exemplary diction. After successful carreer in Europe, Owen returned to the USA, opened voice studios in New York and Boston, joining the music faculty of Boston University. Her many song recitals in both cities over the years garnered high critical praise.

Owen was noted for her master-classes which were among the first to incorporate the Alexander technique in the art of singing. She taught privately in New York City and Los Angeles, and was stage director for Pacific Opera Encore Performances.

A champion of 20th-century American composers, Owen enjoyed close professional relationships with Ned Rorem,David Diamond,Lee Hoiby and Thomas Pasatieri, among others. Her passion for the American art song led her to found the Chloë Owen American Art Song Vocal Competition sponsored for several years by the National Association of Teachers of Singing, New York City chapter (NATS-NYC).

-- Excerpted from the Bach Cantatas website.

BD: Is it just exposure that is needed?

DU: In a way it

’sconditioning and exposure. It has a lot to do with what people are used to, and what they think they’re going to like or not like.

BD: One last question. Is singing fun?

DU: Oh, yes! Fun? Fun is too light a word for it. Singing is usually incredibly gratifying if I’m singing things I care about. And usually, if I’m singing things I care about, and singing them well, singing also feels very natural to me.

BD: I hope you continue caring about it for a long time. Thank you for coming home to Chicago once in a while.

DU: I’d like to come back here more often! [Laughs]

BD: Thank you for spending a little time with me today. I know it’s a busy schedule, and I’m glad we were able to get together.

DU: Oh, I am, too. This was very convenient.

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 25, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few weeks later, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.