Yehudi Wyner Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . (original) (raw)

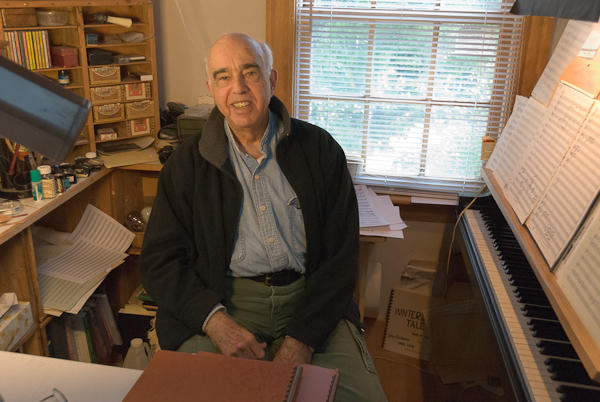

Composer / Pianist Yehudi Wyner

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Yehudi Wyner has created a diverse body of over 60 works for orchestra, chamber ensemble, solo performers, theater music, and liturgical services. In addition to composing and teaching, his active and eclectic musical career includes work as a performer, director of two opera companies, and conductor of numerous ensembles in a wide range of repertory. "A comprehensive musician, Mr. Wyner is an elegant pianist, a fine conductor, a prolific composer, and a revered teacher. His works show a deep understanding of what sounds good and is technically efficient." (Anthony Tommasini, The New York Times, 2009). His wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, has been an enormous source of inspiration; a number of Wyner’s most strikingly beautiful compositions were created specifically for her.

During a quarter-century of doing interviews, I have had the pleasure of meeting many composers and performers who come to Chicago. Their reasons for being in the Windy City are varied, but usually it is for a performance that features their artistry. Occasionally they are just passing through, or have other business here, but this time the reason was both personal and professional. Yehudi Wyner is a fine composer, and his wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, a former singer herself, is a noted conductor. It was her engagement to lead the annual Do-It-Yourself Messiah in December, 1994, that brought them both here, and we arranged to meet.

As happens almost always, it was a genial conversation, with good humor mixed into a serious discussion. Sometimes my guest would digress and go off into interesting but less specific areas, but I was able to pull his focus back to the topic at hand, namely his music and personal opinions.

As usual, throughout this page names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.

As we were setting up for our conversation, Wyner was speaking about his life.. when he started singing

— and quite well, I might add . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Is it important for you, as a working musician, to be able not only to play keyboard, but to sing?

Bruce Duffie: Is it important for you, as a working musician, to be able not only to play keyboard, but to sing?

Yehudi Wyner: Yes.

BD: Why?

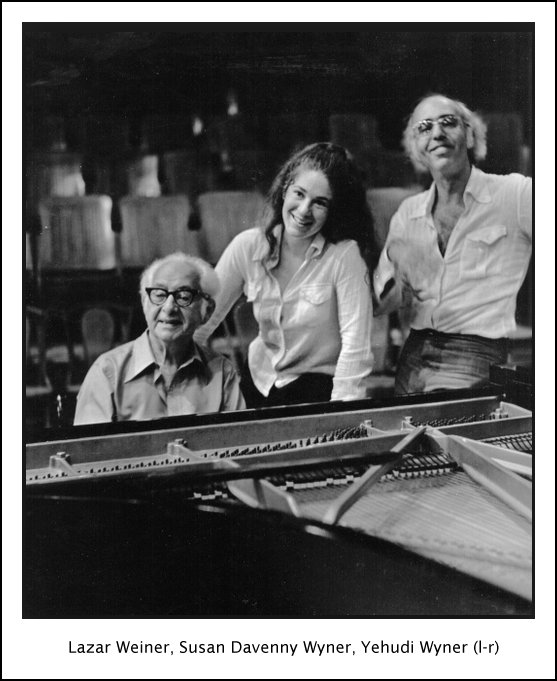

YW: Because I hear my music as singing. I've written a lot of music for voice, and also because while my music sound as if there's a lot of harmonic interest and there's a lot of rhythmic vitality and a lot of rhythmic variation, nevertheless, the real impulse is singing. I sing my own music even if it's complicated parts. I'm in there singing, even if it's kind of monotone, and imagining the way things go. There must be a gene for singing. My father [Lazar Weiner (1897-1982) shown in photo at right] was a great composer of this particular genre; he was the Franz Schubert of the Yiddish art song. That may seem to some people a negligible genre, but in his hands it became a really major expression of an entire culture; a culture which is now fairly much obliterated. This was a Jewish culture which thrived in Eastern Europe, and had maybe two centuries of considerable vitality.

BD: Doesn't it live, though, in your heart and in the hearts of all of the others who have survived?

YW: [Ponders the question] Mmmmmm... Yes, but there actually are relatively few in comparative numbers. I, being born in Canada, and brought up in the United States, may be one of the few who actually speak Yiddish, understand it fairly well and actually can think in it. Most of my peers

— colleagues and people of my age group — learned a few catchphrases and a few slang words, and the names of a few foods. They throw those things out with a good deal of bravado, but the fact is that they really are very much a peripheral part of that culture. Anyway, as a boy, my father sang in synagogue, and was singled out by some very fine musician who had come to visit this little town outside Kiev. This must be about 1910, 1909, 1908, which was not a very good time for the Jews of Russia. There was a great deal of unrest, and as many as possible, who had the courage, would pick up and leave. In any case, this man persuaded my father's parents to allow my father to go with this man and to sing in the great synagogue in Kiev as a member of the choir. His voice was beautiful enough so that eventually he auditioned and became a boy soprano soloist at the Kiev Opera. This was at the time of Chaliapin's heyday, and my father was on stage with such people. He sang there until his voice broke. My father would tell stories about hearing some young prodigy in short pants come through who played the violin... named Jascha Heifetz! [Both laugh] It's fantastic; people who seem so legendary to us and we only think of as being grown up, in many cases he saw them in their formative and pre-transformations. In any case, when my father's voice broke, he went to study the usual piano and theory and so on and so forth at the Kiev Conservatory. Then within two years, the whole family emigrated for America. My father was among those on the last boat out of Danzig. They arrived in New York in 1914 and never left. He made his living first playing in the movies — for silent pictures. Evidently he got to be a crackerjack accompanist and coach, and then bit by bit got involved in choruses. He conducted several organizational choruses and a professional choir.

BD: Did he pass all of this on to you purposely, or did he just let you pick it up by osmosis?

YW: I think it was pretty purposefully and purposely. Evidently there was some kind of manifestation of some musical gift. When I was a kid

—maybe three or four years old — I'd fool around at the piano, and he observed that by the time I was four or four-and-a-half I was making up coherent pieces, which at a certain point no longer changed. In other words, they became real pieces, and he wrote them down for me. Once they were written down, I'd go on to another piece, and when that coalesced and became firm, he would write that down. By the time I was about seven or so I was writing down my own music.

BD: But by the time you started writing, you had a little backlog already.

YW: I already had a considerable backlog of several pieces. I was surrounded by music and music making quite a lot

— not like the Bach family or the Mozart family because my father tended keep his music out of the house for the most part. He worked very hard composing in his little composing room, and it was always an isolated part of the apartment. There were not that many singers and pianists and violinists who came through.

BD: Was it that he didn't want you to have it, or that he needed the isolation to work best?

YW: I think he needed the isolation, and he didn't want to intrude or invade the whole family space. But I had a mother whose campaign was to prime me and cultivate me as a musician, to continue the line. My mother became the instrument of discipline and virtue, and saw to it that once piano lessons began at the age of about five, that I kept to it. She practiced with me.

BD: Did she make it fun?

BD: Did she make it fun?

YW: [With disgust] No! It was an agony! It was something that discolored my entire childhood, and made my perception of it a very, very long, gray, dark, cold, unpleasant afternoon. I don't look back at my childhood with any nostalgia; I look back at it with a great deal of sourness.

BD: But not enough sourness that you would've gone into insurance or something...

YW: I think by the time I would've considered going into insurance

— in the manner of either Wallace Stevens or Charles Ives — I think I was already conditioned to a point where there was no turning back. I would've turned into a pillar of salt, or something! [Chuckles] Or maybe a salt substitute! [Both laugh] It was too late; I was trapped. I knew too much and I was well trained; I played well enough, and there was enough in it for me in those days. Certainly there were times when the discipline ceased and when my rebellion was very open. I rebelled furiously against my parents, and particularly against my mother. So I began to make certain aspects of music, certain kinds of music, my own. I began to respond on my own under my own steam. I can remember the response to a piece like The Rite of Spring. The piece knocked my socks off!

BD: Were you hearing performances or broadcasts?

YW: Performances, actually. I remember hearing it in Carnegie Hall. It might've been with Stravinsky himself conducting. I would go to performances of other things with my father; I went to many, many, many piano recitals at Town Hall, a wonderful hall in New York. There were many performances at Carnegie Hall, but I was often going to hear music and concerts that were chosen on his basis. Rarely was there something that really spoke to me in a very clear tongue.

BD: Did the family want you to go into music being an accompanist and being a musician of the traditional school, or did they want you to strike out and write new music and continue a line of composers?

YW: I think they wanted me to really just get a traditional background in music, and then whatever came, came. Their highest priority, though, was their reverence for the creative musician. The executant, the performer, the singer, was a valuable member of that scheme of things, but was not the prime mover; it was simply the instrument of the prime mover. The prime mover was the composer. My father just had a respect

— more than a respect — he lived for the creative spirit. I can say that very emphatically and without any conditions. Later on in my life, when I grew up and became a full-fledged professional on my own, my father and I still maintained a very close working relationship, a professional relationship of a particular kind. I did a great deal of performing; I performed as a chamber musician, as a solo pianist, as a coach and a player for singers; I conducted, and directed opera companies; I was the organist at a suburban synagogue and wrote quite a lot of music for that. I was really very much in gamba, as the Italian expression goes, as a musician. And my father would reproach me, and remind me very often saying, "What are you doing all of that for?" I'd say, "I love it! I love to do it," and he said, "Creation! That's the only self-expression. That's all that counts. All of this other is nothing."

BD: So he wanted you to be a composer to the exclusion of everything else?

YW: Absolutely. He saw me enthusiastically spending most of my time performing. He saw me, for example, simply immersed in the activities and the affairs of an opera company, directing and coaching and performing, and loving every minute of it. For him, it was just sands through the fingers. It was a waste of time... unless it was to be used in a very systematic way of planning for a career to write opera!

BD: When you were directing opera, did you direct just the standard works or did you try to also push some new works?

YW: The newest works that we got in that opera company were by Benjamin Britten, a few little Stravinsky pieces, a few pieces by Ernst Toch

— a respectable composer, not really a great and inspired composer, but a person of some note...

BD: I enjoyed performing the Geographical Fugue when I was much younger!

YW: The Geographical Fugue is exactly the speed that is the best, but there's a little opera called The Princess and the Pea which you would enjoy somewhat less. It's just too juvenile and the notes are just too trivial. But it was a company that was mostly devoted to traditional values, although it was a very small company in which everything could be handmade.

BD: Let's come back to your own works. You've just made a remark about another composer's work being juvenile and of trivial value. How can you, as a working composer, make sure that your music is not trivial?

YW: I can't! It's only my own conscience and my effort and certainly my aspiration. I have colleagues who feel that I'm wasting my time and I'm kidding myself, and that I'm writing juvenile and trivial compositions!

BD: But obviously you don't!

YW: I don't think so at all, but it depends on which pieces. That's my opinion. That also may be a trivial, juvenile opinion. We're talking about opinions and self-evaluation, the evaluation of peers, not to speak of the evaluation of history. Trying to predict what it's going to be like in many years is not a very good pursuit, it seems to me. We're also talking about criticism of people who are in fields other than your particular specialty, shall I daresay even people on the street and people from other cultures. The evaluations are fast and furious and all over the place. I'll give you an example of how difficult it is to really determine anything absolutely. In 1989 I wrote a set of choruses for women's chorus. My wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, was directing a women's chorus at Cornell, where she was head of vocal studies. It was a year honoring women's cultural achievements, and she asked if I would write a cycle or a group of songs to women's poetry. I found some marvelous poems by Marianne Moore [(1887-1972), American Modernist poet and writer noted for her irony and wit]. The principal one was "O To Be a Dragon." That sounds like a very silly little poem, and the second turned out to be about a jellyfish. The third is "To a Chameleon," and the fourth was a poem which had a very whimsical title, "To Victor Hugo of My Crow Pluto." It's a mouthful, but it's a rather delightful one. She made up a whole mythical creature

YW: I don't think so at all, but it depends on which pieces. That's my opinion. That also may be a trivial, juvenile opinion. We're talking about opinions and self-evaluation, the evaluation of peers, not to speak of the evaluation of history. Trying to predict what it's going to be like in many years is not a very good pursuit, it seems to me. We're also talking about criticism of people who are in fields other than your particular specialty, shall I daresay even people on the street and people from other cultures. The evaluations are fast and furious and all over the place. I'll give you an example of how difficult it is to really determine anything absolutely. In 1989 I wrote a set of choruses for women's chorus. My wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, was directing a women's chorus at Cornell, where she was head of vocal studies. It was a year honoring women's cultural achievements, and she asked if I would write a cycle or a group of songs to women's poetry. I found some marvelous poems by Marianne Moore [(1887-1972), American Modernist poet and writer noted for her irony and wit]. The principal one was "O To Be a Dragon." That sounds like a very silly little poem, and the second turned out to be about a jellyfish. The third is "To a Chameleon," and the fourth was a poem which had a very whimsical title, "To Victor Hugo of My Crow Pluto." It's a mouthful, but it's a rather delightful one. She made up a whole mythical creature

— I think it's mythical, although in one book Moore writes about this creature as if it were real and who learned to be her friend.

BD: It was real to her!

YW: Yes, [chuckles] we could get into the whole business of virtual reality. She wrote about it one book of commentary, and described it as a real live story, but it seemed unlikely. In any case, she grew very fond of this bird and eventually set it free. There was something in a title or a preamble of some sort, written by Victor Hugo, which translated was, "Even when the crow is walking, we know that it has wings." I wrote a series of choruses which used a great many vernacular quotations, or not quotations but atmospheres. For example, one of them was like a disco song; another had a lot of jazz elements; another one had aspects of tango, and so on and so forth. These are kinds of things that I like a lot. How one does this without making pastiche or making a collage does not interest me very much; I'm interested in the transformation of these materials. I'm interested in the synthesizing of those which are coming into my perception and then coming out filtered through my temperament, whatever my purposes are, so that they come out, suddenly, in a another place. They come out in another world with another expressive meaning.

BD: Can you predict where this world is, or what it's going to look like?

YW: Never! I never can, but there is always a turn, somewhere, of a certain implicit ferocity or expressiveness; a certain pathos, even, taking something that just seems, on the surface, joyous and just fun and loping along, and suddenly there's a turn and something happens... I mean like that Joseph Heller novel. [Note: Something Happened is Heller's second novel, published in 1974, 13 years after Catch-22.] For me, that's very important in composition altogether, in all my compositions. No matter what style I'm tending towards, no matter what the scale of the piece, something always happens.

BD: Is that how you know a piece is working, because something is happening?

YW: In my opinion, yes. Yes! I love these pieces, although they were, in a sense, fluff, but no less fluff than, let's say, Ravel's Valses nobles et sentimentales, or some little pieces of Debussy such as The Girl with the Flaxen Hair, or En bateau. There are pieces, especially by French composers, which deal with lyric material with a light touch, and yet transmit musical values which are no less elegant, no less refined, not necessarily learned but no less witty or bearing information and feeling than things which are written with [begins to speak in a low tone of voice for comic effect] long faces, you know, well thought-about retrograde canons, and God knows what. [Both chuckle] Anyway, I loved these pieces, and almost all my musician friends who came in contact with them just loved them. And people singing them adored them. While teaching at Harvard, I was walking through the Harvard Yard there were four handsome young ladies who were just skipping through the yard, singing "O To Be a Dragon." I was dumfounded! I said, [in a perplexed half-whisper] "What is that?" and they said, [with great excitement] "Oh, we're singing it in chorus and we just love it!!" I said, "I wrote that music," and they turned on me as if they couldn't believe it, as if I was a ghost! It was one of the high points of my life. On the other hand, I played it for one of my really most deeply respected colleagues. He listened to it without cracking a smile, and when it was over, he said, [in a blasé tone of voice] "Yeah, they're fun."

BD: Obviously he missed the whimsy.

YW: He didn't like them; he didn't respect them; he thought I was wasting my time. He thought they weren't serious enough, and they're fun! Well, that certainly was an intention. Music is very serious business for me, and there's a lot of struggle involved in my relationship with music. When I'm having fun doing it, it's a real breakthrough of a kind. But for me, fun is not writing garbage. What I feel is the craft, the refinement. The effort for closure, the involvement of various elements in it, still remains as intense as it does for a so-called "serious" piece.

BD: Mozart wrote some divertimenti!

YW: And even the Musical Joke! [Both chuckle for a moment, thinking about this humorous work] I've had a lot to do with Bach, and often on tour we do funny pieces, likeAeolus! [Der zufriedengestellte Aeolus(Aeolus Pacified, 1725) is one of Bach's secular cantatas, BWV 205. Although published under that title, Bach's original title was Zerreißet, zersprenget, zertrümmert die Gruft (Destroy, Break and Shatter the Tomb).] Bach wrote this funny birthday piece for professor Müller, a man whom he admired and helped, whose birthday he celebrated for the university. [Dr. August Friedrich Müller (1684-1761) was a professor of philosophy and law at the University of Leipzig.] The piece has got all the same moves as the great works of Bach; there's nothing cheap about it, with complicated recits, fugues, ritornellis and real arias, duets, choral pieces; it's a big deal! [Speaking deliberately] Same music.

BD: One of my favorite questions is "what is the purpose of music?" but in this instance, let me ask, "What are some of the purposes of music?"

YW: [Thinks for a moment] Tonight I was participating in the annual Do-It-Yourself Messiah, which seems to take place every season around Christmas at Orchestra Hall. [Begun in 1976 under the direction of Margaret Hillis, Susan Davenny Wyner took over for several years starting in 1990.] About halfway through the performance, I noticed out of the corner of my eye an attractive young woman, I would say in her twenties with red hair, who was listening to one of the arias. She was listening with her eyes open, unblinking, with her mouth open. She was drinking in this experience! Every gesture of the singer, every shape of the music was reflected in the exact expression in her eyes and the tilt of her head. This was an experience which was more important, more significant for her, than food. I would imagine that she eats with appetite, but with a certain amount of, let's say, unnuanced indifference; she's just chomping. The music was a full communication of the highest, most aspirative values that she could conceive. I remember being very struck by the opening scene of The Magic Flute movie that was shot by Ingmar Bergman. During the playing of the overture, the whole point was to play the overture in full and simply to take shots of the audience listening to it. Those shots indicated a spiritual involvement in a world that was so profound, so unspeakable and so essential to these people that nothing could replace it. It wasn't exactly a religious or spiritual experience; it wasn't exactly a bodily physical experience. It synthesized and harmonized everything in these people's lives, and the point was that they were utterly transported out of themselves. Think how little time we spend truly transported out of ourselves. Most people, I think, don't find that in work. Many find it in their addiction to sports

— not so much participatory, because we have too little of that, but certainly as spectators, both in the stadium, but even more on TV, for some reason. But that's an experience which is constantly being broken, somehow, by one's expostulations, and by one's feeling of the competitive aspect of things. There's a great deal of negativism. [Speaks in a gruff, angry "tough guy sports fan" tone of voice] "That bastard! How did he make that play??? It was awful!!" Or, "The call of the referee was monstrous!!! He's crazy!! What's the matter with him??? They should replay it." There's a great deal of feeling other than benign and constructive.

BD: And yet when your team scores a touchdown, then the four or five of you around the set are all screaming and hollering!

BD: And yet when your team scores a touchdown, then the four or five of you around the set are all screaming and hollering!

YW: You're screaming and hollering, but it's almost always at someone else's expense

— the poor sucker down the hall who's rooting for Cleveland when you're in Chicago! There is not that kind of aspect of appreciation of music. Now that's not its only function, to be sure, but when I see something like this young lady, I see the transforming power of music. I see it among students sometimes at the various places that I've been. I'm under no illusions that music can improve the human being. I don't believe that. However, the unpleasant composers of music and the egotistical performers of music, when they function in their chosen field, become angels. When they function amongst humankind, they just return to their commonplace pettiness, which is sometimes very noble, and sometimes just unpleasant. I was just reading a rather popular biography of Brahms, learning a number of things about him — most of them admirable, but some of them surprising! With his good friend Joachim, who collaborated with Brahms under many circumstances both as a player and then as an advisor for the Violin Concerto and his other string pieces, it wasn't always smooth sailing between them. There were some years where they broke up; they really had enough of each other. One said the other was a very egotistical person. Joachim said about Brahms that he was mostly genius and wonderful, but every now and then he became very absolutist, had to have his own way and became extremely pedantic and unpleasant. And that was even how Clara Schumann felt about Brahms.

BD: But whenever you have strong personalities, there's going to be a clash.

YW: Strong personalities either may clash, or they suffer the disorders of the human race! We all are, as my father used to say, "damaged goods." [Laughter] We're all damaged goods. Otherwise who would need redemption? Otherwise, who would need resurrection? Otherwise, who would need confession and improvement? Here I'm coming from a performance of Messiah, so all these concepts really tie in not just with religious concepts, but with our normal conduct of life!!

BD: Should your list include, "Otherwise, who would need music?"

YW: Well... [thinks for a moment] no. I think music is an appetite and not a need. No matter whether some of us feel that classical music

— as it has been practiced and appreciated — is not in ascension these days, not in training programs, not amongst broadcasters for the most part, not in publishing houses and so on and so forth. Nevertheless, there's a lot of it around! But whether it's classical music or whether it's world music or whether it's Afro-pop or whether it's new music from Brazil or whether it's ragtime or whether it's rap, the appetite to hear music is so potent. I can't get into a cab now without somebody having music on. And who am I to criticize what that music is? I can ask the cabbie to shut it off, but only on one condition would I do that — if I'm trying to continue a musical thought in my head, which will be obliterated by this other thing. But otherwise it's alive! It's helping these people. They need it! It's not just a soporific — that is, it's not just putting them to sleep. It's not an opiate, listening to it as wallpaper; it's a participatory thing. Many of them sing along; they know the words. It's not just background "elevator music" or wallpaper. [Musing wistfully] My father knew the man who invented Muzak.

BD: [Laughing] I don't know if he's to be congratulated or not...

YW: No, he didn't think of it as a great achievement. This fellow was very rich and famous and said he appreciated new music, so he sent him to visit me in Rome. I had won the Rome Prize in 1956, and was living in Rome for two or three years in a state of sort of official splendor. All I had to do was write music, and if I didn't want to do that, I didn't have to do that. I had no boss, nobody to be responsible for, and every need was taken care of. I had a little studio in a little 16th-century farmhouse that actually Liszt had once visited. During his lifetime in the 1800s, he visited this little beamed cottage. I had a grand piano in there and a cot. It had a usual kind of low ceiling and it looked like La bohème. So this fellow came and visited me, and he was very impressed with the general surroundings of the Academy

— which is a grand building — and then he came out to the garden and wanted to know what I was writing. At the time I was writing a sonata for piano, and he wanted to hear that. So I ripped through it as a virtuoso piece. These were my formative years, so it's got someElliott Carter in it, some Stravinsky, some Copland, even some Haydn. It also had some me in it! [Laughs]

BD: I was going to ask if it also had some Wyner in it.

BD: I was going to ask if it also had some Wyner in it.

YW: Who knew? Who can tell? Who knows when you're yourself? It's an accumulative thing you find when you look back.

BD: I assume you eventually have to find yourself, and that's what you were doing over in Rome.

YW: [Very skeptically] Yeah, but a lot of people think that they find themselves by really looking. I think you find yourself by doing, and if you have a spark of individuality, it's willy-nilly going to come out! If you start to look very deliberately for some signs of originality, you're likely to come up with some plastic imitation of some other person's so-called originality. I don't think it happens like that. Beethoven really was original only in the sense that he had a very particular temperament. His style was totally unoriginal until the Eroica, when things started to happen.

BD: Is your music original now?

YW: I think my music is somewhat recognizable. There are certain things that happen in a lot of my pieces, and people who know quite a lot of my music say they feel there is a presence there; they feel there's an individuality that they recognize.

BD: Does that give you a good feeling?

YW: Yes it does, not so much because it's original, but because I think it's well made, and above all because I think it says something, and I think it's eloquent. When my music is understood or when it's well performed, I think it's very moving. There's a transformation that happens. There's something that is said that seems to engage people's feelings at a rather deep level, and sometimes at a very amusing level. Sometimes there are things that they think are very smart or very "clever"; I don't really like the word very much, as it implies kind of superficiality, but certainly I'm very appreciative of the fact that people recognize that it's well made. The business at hand is taken care of, and that's important. I remember resenting a teacher I had at Yale. As an undergraduate, I came to Yale and one of my teachers

— who really had a fine influence on me and who ended up being a very level guide and mentor — was a man named Richard Donovan (1891-1970). He was very good to me. He was a fine composer, though not at all a composer to my taste; his music was much, much too dry. But he was moral, ethical, and while his music was not forward-looking, he himself allowed forward-looking influences. He was the man who brought Hindemith to Yale. He was the man that made Yale conscious of Bartók's music. He was the man who was behind trying to bring Schoenberg to Yale. Schoenberg was invited, but demanded that Yale move him and pay for the moving. The moving was too expensive, so Yale threw up its hands and said, "He's not worth it." In any case, Donovan would hear these emotional statements that I'd be making about what it was I wanted to get out of this piece. I wanted the piece to really have a kind of involvement and a kind of climactic resolve. I'd be talking about it and he would look at me dryly and just say, "Get the job done. Just get it on the way."

BD: Was he right?

YW: Uhhhh, no. [Both laugh] He wasn't right. I don't think he was right but I think what he sensed was that my danger was in getting too emotionally involved, and maybe not taking care of business. We're good friends withAndré Previn. We spend time together, and one of André's favorite things when he speaks to an orchestra, is, "Let's get on with it! Let's just get on with it!" He doesn't go in for long, eloquent explanations; he'll just suggest a phrasing or something like that. There's an amusing story... He was conducting last summer at Tanglewood, and a piece that the Boston Symphony Orchestra had not done for a long time was the Classical Symphony by Prokofiev. So they ran it through at rehearsal, and when they came to the end it was a pretty ragged, rough and ready performance. Previn just looked at the orchestra for a minute, and he said, "All right, let's just play it again, but please play it better." [Both laugh] They had just been through the notes; they are master musicians and can play as well as anybody in the world. He had seen where the trouble spots were, so they were all ready! He conducted with slightly greater definition. They listened and they looked and they played, and they really gave a rip-roaring performance of the piece. You can get involved in all kinds of involutional [in an intense, almost ferocious tone of voice] suggestions for how to achieve this affect and this inner line...

BD: Better to just get on with it!

YW: Right, get on with it! I've learned to get on with it, but certainly to really craft pieces so that they stand up. They stand up through many performances, and they stand up through that inevitable process that every performer has to go through. You have got to get the notes down. If the notes aren't right, if the local event isn't right, if it doesn't make sense, if it doesn't give both physical and aural satisfaction, why is the performer going to keep at it? Since I'm a performer, I'm very sympathetic to that. I've had some time to do assignments, to play pieces which were badly made

YW: Right, get on with it! I've learned to get on with it, but certainly to really craft pieces so that they stand up. They stand up through many performances, and they stand up through that inevitable process that every performer has to go through. You have got to get the notes down. If the notes aren't right, if the local event isn't right, if it doesn't make sense, if it doesn't give both physical and aural satisfaction, why is the performer going to keep at it? Since I'm a performer, I'm very sympathetic to that. I've had some time to do assignments, to play pieces which were badly made

— I mean badly made! — where the notes were indifferently chosen, where the physical effort to achieve some semblance of the notation at the tempo given was immense, or the skips or the fast moves were ridiculous; the sonorities were ugly or they were not really resonating or they obliterated another part. There are any number of possible viruses that can enter the body politic of music, and I resented every minute having to do that kind of dog work when there was no payoff. I wasn't willing to wait the five months until the piece would be in its final form, where I could go out and give a smash-bang performance of it one time, and in order to do that I would have had to sacrifice my life to this moment-to-moment thing. We find in working on the great music of the past, that every moment has an excitement. Bach, for example, from that point of view is the be-all and end-all. You can play anything of Bach and you will get the message.

BD: You can't kill it.

YW: Not only can you not kill it, it continues to make you live.

BD: But he's the pinnacle.

YW: He is the pinnacle, but he's also the model. He's the aspiration. He is, in a sense, the archangel, and if we don't work towards having that aspiration, then we're lost. We can't be like Bach, but I certainly know where that standard lies, and the closer I can come to it, the happier I am. I must say I've actually aspired to be much less towards the line of Bach than somebody much closer to my temperament, someone like Mozart. I felt about these dragon choruses

— the choruses for women's chorus that I was mentioning before — that finally I had begun to approach not the quality of Mozart, but begun on that path to begin to understand those balances of the gallant, the playful, the graceful, the nice-sounding, the pleasant and alluring surface, with the tensile values, the tensions and the forces that carry a more serious message beneath. People who think that Mozart's a tinkler and writing pretty music miss the message. Other people who merely present him as a demonic composer, without those surface allurements also are mistaken. It's all things.

BD: When you are teaching, is this the kind of advice that you give to your students?

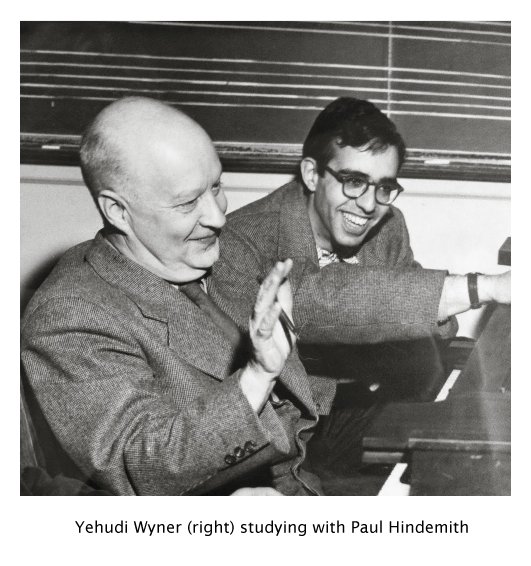

YW: Yes, I think I help my students to the extent that I really try to use the most constructive aspects of my own relationship with teachers and my own experiences as a student. I do try to help them. I've had experiences with teachers which I felt were not positive, which were not helpful, even from great teachers who meant well. Hindemith, for example, was a mixed bag. The things I learned from Hindemith were not the things he was trying to teach me.

BD: The report on Hindemith is that he was trying to create lots of little Hindemiths.

YW: The report has a modicum of truth, but it doesn't quite understand that Hindemith had nothing but contempt for the little Hindemiths that he would create. Hindemith was like a very possessive father. He himself had no family, and I've always thought that his students were his extended family. The ones that he ended up respecting were the ones that fought with him, the ones that defied him, the ones that just were not going to have any of it. They were not going to buy that sort of thing. He actually would fight them and would try to impose his will, and if he didn't succeed he was somewhat happier. The others he was friendly to, but he simply dismissed them. That's not generally understood and not generally known. Yes, there was that instinct to create little Hindemiths, but the ones who succumbed ended up being, in his eyes, just useless people.

BD: Was he looking, then, for the strength to stand up to him?

YW: Yeah, but it wasn't even a deliberate test. It wasn't like a Magic Flute, where you have to pass tests in order to end up being Tamino and Pamina. It wasn't that thought-out. He was a man also possessed by his own demons; very competitive.

BD: Are you basically pleased with what you see coming off the page of your students?

YW: [Thinks for a long while] I find that a difficult question to answer partially because I think there is a very confidential relationship that exists between a teacher and his students. For that reason, I see my composition students one-on-one. I have colleagues who somehow manage to see the whole group and share that with the whole class. In my own experience I didn't like it; I didn't enjoy that. I really wanted the absolute individual undivided attention of my teacher, and when I didn't get it I was rather bored. That was my own problem; I was unable to enter the worlds of some of my colleagues, or some of my peers. But if you think about it, if I just said baldly, "Yes, I'm very pleased with the work that comes out of my students," there'd be a certain amount of self-aggrandizement in that. I would be taking credit for what's coming out. If I said, "No, I just think they're a bunch of slobs and slouches and they don't really match up," that would not be such a good thing even if they didn't hear about it. [In comically exaggerated deep tone of voice, imitating a busybody] "I heard your teacher said that he doesn't like the work of his students!" Then the student confronts me and I start to blubber! Then there are the students who write music that frankly I don't understand! Am I going to admit that to them? Well, I do, and I try to help them in other ways. There are manners of encouragement where you don't really understand exactly what's up. You don't always meet with a sympathetic reception. Milhaud is reported to have said in an interview, "Boulezloathes my music. He detests my music, but he performs it better than anybody in the world." So I think I can help my students even when I don't understand what they're doing, which happens; even when I don't approve of what's coming off the page, which happens; and even when I think what they're doing is wonderful. That happens also. They do all happen, and sometimes they don't happen in my presence. It may not happen while I'm with them. It may happen later on, and the appreciation might come. Or some of the seeds that are planted may germinate and bear some fruit. But one never knows. You know so little about your children and their lives; you know so little about your students and their lives.

YW: [Thinks for a long while] I find that a difficult question to answer partially because I think there is a very confidential relationship that exists between a teacher and his students. For that reason, I see my composition students one-on-one. I have colleagues who somehow manage to see the whole group and share that with the whole class. In my own experience I didn't like it; I didn't enjoy that. I really wanted the absolute individual undivided attention of my teacher, and when I didn't get it I was rather bored. That was my own problem; I was unable to enter the worlds of some of my colleagues, or some of my peers. But if you think about it, if I just said baldly, "Yes, I'm very pleased with the work that comes out of my students," there'd be a certain amount of self-aggrandizement in that. I would be taking credit for what's coming out. If I said, "No, I just think they're a bunch of slobs and slouches and they don't really match up," that would not be such a good thing even if they didn't hear about it. [In comically exaggerated deep tone of voice, imitating a busybody] "I heard your teacher said that he doesn't like the work of his students!" Then the student confronts me and I start to blubber! Then there are the students who write music that frankly I don't understand! Am I going to admit that to them? Well, I do, and I try to help them in other ways. There are manners of encouragement where you don't really understand exactly what's up. You don't always meet with a sympathetic reception. Milhaud is reported to have said in an interview, "Boulezloathes my music. He detests my music, but he performs it better than anybody in the world." So I think I can help my students even when I don't understand what they're doing, which happens; even when I don't approve of what's coming off the page, which happens; and even when I think what they're doing is wonderful. That happens also. They do all happen, and sometimes they don't happen in my presence. It may not happen while I'm with them. It may happen later on, and the appreciation might come. Or some of the seeds that are planted may germinate and bear some fruit. But one never knows. You know so little about your children and their lives; you know so little about your students and their lives.

BD: You just do the best you can.

YW: You do the best you can. You get on with it, so to speak. [Both chuckle] I'll tell a funny story on myself. I do a lot of cooking. I love to cook, and the specialty that I've carved out for myself has been Chinese food. After compensating for the lack of a proper stove and what the Chinese call the "big fire," we moved to a significantly modified older house in Medford, Massachusetts, which is a small suburb of Boston. The major thing in the kitchen was to have built a wok stove in full regalia, with the appropriate exhaust system, a "big fire," and the insulation and all the things necessary. That's really one of my great joys; it's a great sport for me, and the cooking that comes out of it, I tell you, it's hard not to blow up like a balloon! Anyway, a student from Yale came up to me years later and said, "Oh, Yehudi... You know those were wonderful years at Yale. You know what I remember the best?" I'm there with all ears, my tongue's hanging out and my eyes are open wide. I'm waiting for this student to tell me of some significant word of wisdom, some encouragement, some germ that now has seeded itself.

BD: [Anticipating] It was the food! [Both laugh]

YW: He said, "It was that party you threw for us where you cooked for us outside in your backyard!" [Laughs] I said, "Yes, that's the poetic justice." Well, at least he remembered something.

BD: But he did remember you!

YW: He remembered, yeah.

BD: But he associated you with a very great event, so there you are! [Noting Wyner's dejection] I'm always looking for the optimistic thing.

YW: The optimistic thing? I like the idea. I admire optimists, though I'm not one myself.

BD: [Surprised, in light of Wyner's cheerful demeanor throughout the interview] Really??? Not at all???

YW: No. Not really. I may be very lively and filled with activity. But my view, my general cast of mind is not an optimistic, can-do one.

------- Note: Normally I would have pursued this topic a bit, but at this point the tape recorder stopped at the end of the cassette-side, and we both realized that we needed to push on to other appointments. I thanked him for meeting with me and for all the music he had given us, a remark which seemed to please the composer very much.

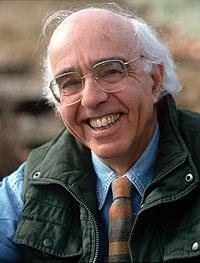

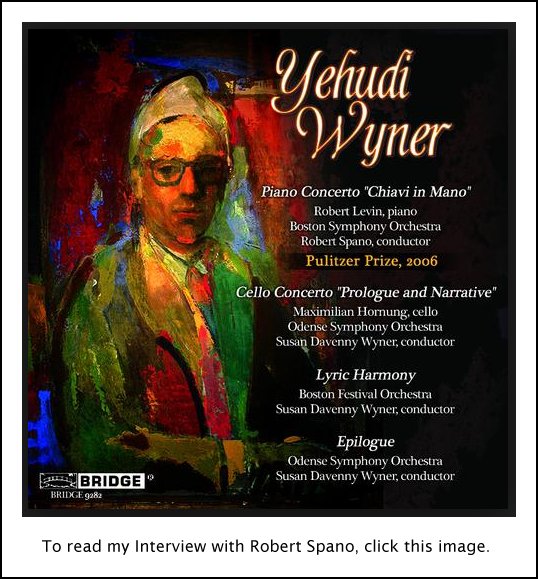

Since the time of our meeting in 1994, Wyner has continued to write and teach, and has won awards including the Pulitzer Prize in 2006. More details of his career are included in the box below, which is supplied by his publisher, G. Schirmer Inc.

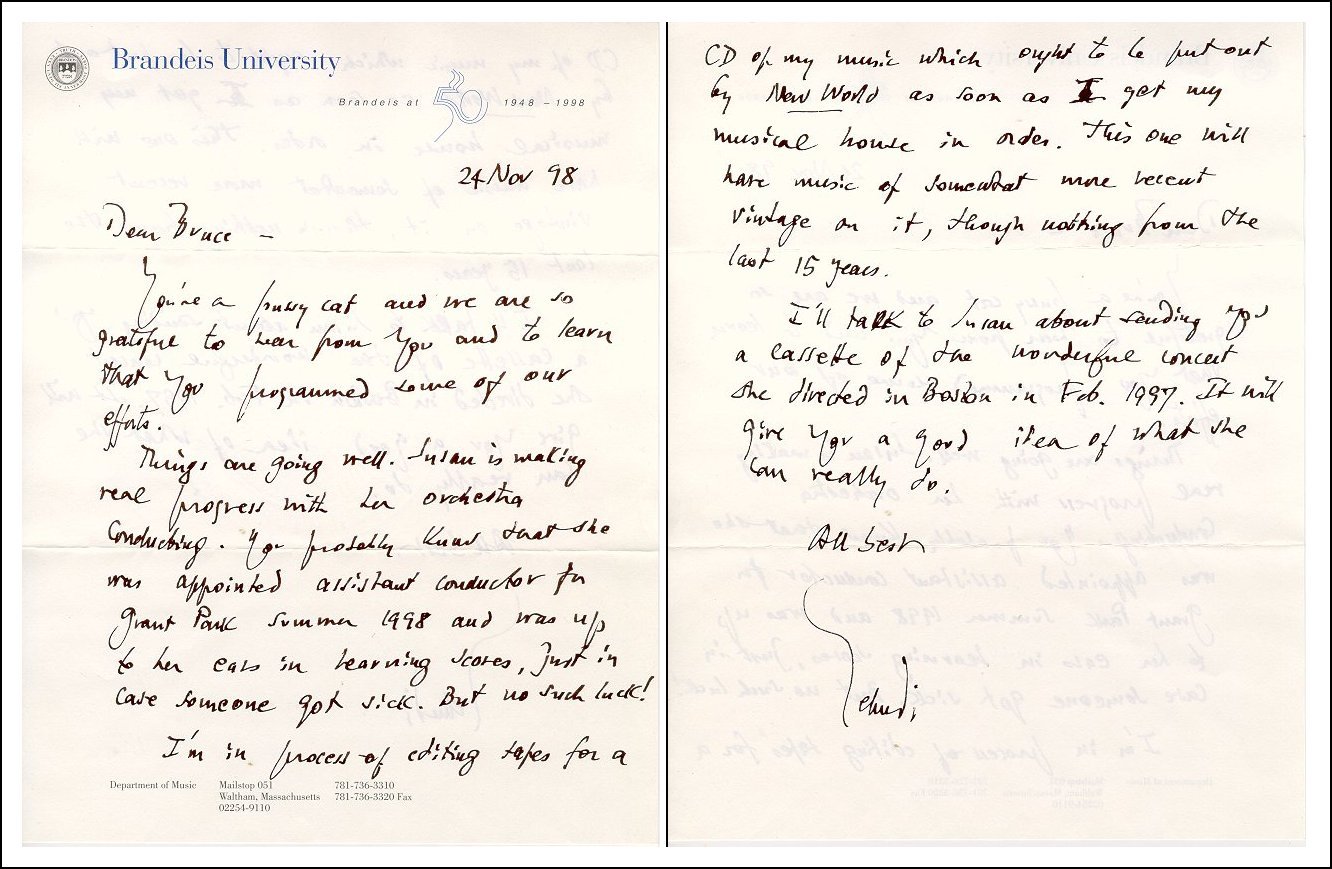

When producing programs which aired on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, I would usually send my guests the Program Guideshowing their specific listing. Sometimes the guests would respond, and in those ancient days before e-mail, communications took the form of typed or hand-written notes! Below is the one I received after doing a program for Wyner's wife, Susan . . . . .

I'm not sure I've ever been called a "pussy cat" either before or since, but it would be appropriate because the station famously kept cats and dogs on the premises! Here is a photo where I am holding Abigail (a cat) in the record library, and here is one showing me with the station manager and one of the dogs (named Sparky).

One last item about the interview above... As I was packing up the recording equipment, Wyner mentioned his good friend, the flutist Samuel Baron [both pictured immediately below]. Naturally I asked for contact information so that a meeting could be arranged, and that conversation is posted here.

Wyner was born in Western Canada and grew up in New York City in a musical family. His father, Lazar Weiner, was the preeminent composer of Yiddish Art Song as well as a notable creator of liturgical music for the modern synagogue. This early exposure paved the way for a Diploma in piano from The Juilliard School and further musical studies at Yale and Harvard Universities with composers Richard Donovan, Walter Piston, and Paul Hindemith. A Handel course at Harvard brought Wyner to the attention of Randall Thompson, who became a staunch supporter and friend. In 1953, Wyner won the Rome Prize in Composition enabling him to spend the next three years at the American Academy in Rome, composing, performing, and traveling. Since then, he has received many honors including the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in Music for his **Piano concerto "Chiavi in mano,"**two Guggenheim Fellowships, a grant from the American Institute of Arts and Letters, and the Brandeis Creative Arts Award. In 1998, Wyner received the Elise Stoeger Award from Lincoln Center's Chamber Music Society for his lifetime contribution to chamber music. His Horntriowas a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1998, and in 1999 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Wyner was born in Western Canada and grew up in New York City in a musical family. His father, Lazar Weiner, was the preeminent composer of Yiddish Art Song as well as a notable creator of liturgical music for the modern synagogue. This early exposure paved the way for a Diploma in piano from The Juilliard School and further musical studies at Yale and Harvard Universities with composers Richard Donovan, Walter Piston, and Paul Hindemith. A Handel course at Harvard brought Wyner to the attention of Randall Thompson, who became a staunch supporter and friend. In 1953, Wyner won the Rome Prize in Composition enabling him to spend the next three years at the American Academy in Rome, composing, performing, and traveling. Since then, he has received many honors including the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in Music for his **Piano concerto "Chiavi in mano,"**two Guggenheim Fellowships, a grant from the American Institute of Arts and Letters, and the Brandeis Creative Arts Award. In 1998, Wyner received the Elise Stoeger Award from Lincoln Center's Chamber Music Society for his lifetime contribution to chamber music. His Horntriowas a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1998, and in 1999 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Among Wyner's most important works is the liturgical piece Friday Evening Servicefor cantor and chorus, and it is this piece that initiated his relationship with Associated Music Publishers. The composer elaborates, "The circumstances of my initial contact with Schirmer/AMP [came about] in the spring of 1963, [when] the premiere of my new Friday Evening Servicetook place at the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York. The next day, I received a call from a person, then unknown to me, named Hans Heinsheimer [former G. Schirmer Director of Publications]. After identifying himself, he said that Samuel Barber had attended the premiere and urged Heinsheimer to be in touch with me to discuss a possible publishing relationship. Of course I was astonished!"

Wyner has been commissioned by the Ford Foundation, the Koussevitzky Foundation at the Library of Congress, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival, Bravo! Vail Valley Music Festival, Michigan and Yale Universities, and many chamber music ensembles including Aeolian, DaCapo, Parnassus, Collage, No Dogs Allowed, the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, and 20th Century Unlimited. Recordings of his music can be found on New World Records, Naxos, Bridge, Albany Records, Pro Arte, CRI, 4Tay Records, and Columbia Records.

Since 1968, Wyner has been a keyboard artist for the Bach Aria Group. In this capacity he has performed and conducted a substantial number of the Bach cantatas, concertos, and motets. He recently retired as the Walter W. Naumburg Professor of Composition at Brandeis University, a post he held since 1991. He also taught at Yale University as head of the Composition faculty, at SUNY Purchase as Dean of the Music Division, as a visiting professor at Cornell and Harvard Universities, and as a member of the chamber music faculty at the Tanglewood Music Center from 1975 to 1997. He has been composer-in-residence at the Sante Fe Chamber Music Festival (1982), the American Academy in Rome (1991), and the Rockefeller Center at Bellagio, Italy (1998).

His notable orchestral works include: Prologue and Narrative for Cello and Orchestra (1994), commissioned by the BBC Philharmonic for the Manchester International Cello Festival; Lyric Harmony for orchestra (1995), commissioned by Carnegie Hall for the American Composers Orchestra; and Epilogue for orchestra (1996), commissioned by the Yale School of Music. Notable works for smaller ensembles include: String Quartet (1985); Toward the Center for piano (1988); Sweet Consort for flute and piano (1988); 0 To Be a Dragon choruses for women's voices (1989); Trapunto Junction for horn, trumpet, trombone, and percussion (1991), commissioned by the Boston Symphony Chamber Players;Praise Ye the Lord for soprano and ensemble (1996), commissioned by Dawn Upshaw and the 92nd Street Y; Horntrio(1997), commissioned by Worldwide Concurrent Premieres Inc. for 40 ensembles; Madrigal for String Quartet (1999), commissioned by the Lydian String Quartet at Brandeis; The Second Madrigal: Voices of Women (1999), commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation at the Library of Congress; Tuscan Triptych: Echoes of Hannibal for string orchestra (2002); Commedia for clarinet and piano (2002), commissioned by Emanuel Ax and Richard Stoltzman; and Trio 2009 for clarinet, cello, and piano (2009), commissioned by the Chamber Music San Francisco.

His music is published by Associated Music Publishers, Inc.

— November 2011

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 19, 1994. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB two months later, and again in 1999. It was also used on WNUR in 2009 and 2010, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2009. An audio copy was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made and posted on this website late in 2011.

To see a ful list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.