Caustic Ingestions: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

Caustics and corrosives cause tissue injury by a chemical reaction. The vast majority of caustic chemicals are acidic or alkaline substances that damage tissue by accepting a proton (alkaline substance) or donating a proton (acidic substance) in an aqueous solution. [1]

The pH of a chemical is a measure of how easily the chemical accepts or donates a proton. This relates to the strength of the acidic or alkaline substance, and provides some, but not precise, correlation with the likelihood of injury. Substances with a pH less than 2 are considered to be strong acids; those with a pH greater than 12 are considered to be strong bases.

The severity of tissue injury from acidic and alkaline substances is determined by the duration of contact; the amount and state (liquid, solid) of the substance involved; and the substance's physical properties, such as its pH, concentration, ability to penetrate tissue, and titratable reserve (ie, the amount of tissue required to neutralize a given amount of the involved substance). Titratable reserve is particularly useful for measuring the amount of damage that can be caused by caustics, such as phenol, that have a near-neutral pH.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation in patients with caustic ingestions may be deceptively unremarkable, even in patients with significant tissue necrosis. However, the presence of any of the following suggests the possibility of significant internal injury:

- Dyspnea

- Dysphagia

- Oral pain and odynophagia

- Chest pain

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea and vomiting

Signs of impending airway obstruction may include the following:

- Stridor

- Hoarseness

- Dysphonia or aphonia

- Respiratory distress, tachypnea, hyperpnea

- Cough

Indications of severe injury include the following:

- Altered mental status

- Peritoneal signs

- Evidence of viscous perforation

- Stridor

- Hypotension

- Shock

See Presentation for more detail.

Workup

Obtain an upright chest radiograph in all cases of caustic ingestion. Findings may include pneumomediastinum or other findings suggestive of mediastinitis, pleural effusions, pneumoperitoneum, aspiration pneumonitis, or a button battery (metallic foreign body).

Endoscopy is generally indicated for the following patients:

- Small children who are not tolerating liquids or with complaints of pain

- Patients with a disk battery ingestion identified in the esophagus or stomach

- Symptomatic older children and adults

- Patients with abnormal mental status

- Patients with intentional ingestions

- Patients in whom injury is suspected for other reasons (eg, ingestion of large volumes or concentrated products)

Because of the risk of iatrogenic injury, esophagoscopy should not be performed in patients with any of the following:

- Evidence of esophageal or gastrointestinal perforation

- Significant airway edema or necrosis

- Hemodynamic instability

- Delay of more than 24 hours since the ingestion

See Workup for more detail.

Treatment

Note the following:

- Airway monitoring and control is the first priority.

- Gastric lavage is contraindicated, but nasogastric tube suction may be beneficial if performed promptly after large-volume liquid acid ingestions, especially of zinc chloride, mercuric chloride, or hydrogen fluoride.

- In asymptomatic patients, observation for 2-4 hours may be appropriate if the clinician has no unique concerns regarding the ingested substance.

- In symptomatic patients, arrangements should be made for urgent esophagogastroduodenoscopy to grade the degree of injury and establish long-term prognosis.

- Surgical consultation is indicated for suspected perforation. Because of the risk of late complications—most commonly, esophageal stricture formation—arrangements for follow-up need to be made.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Pathophysiology

Caustic chemicals produce tissue injury by altering the ionized state and structure of molecules and disrupting covalent bonds. In aqueous solutions, the hydrogen ion (H+) produces the principal toxic effects for the majority of acids, whereas the hydroxide ion (OH-) produces such effects for alkaline substances.

Alkaline ingestions

Alkaline ingestions cause tissue injury by liquefactive necrosis, a process that involves saponification of fats and solubilization of proteins. Cell death occurs from emulsification and disruption of cellular membranes. The hydroxide ion of the alkaline agent reacts with tissue collagen and causes it to swell and shorten. Small-vessel thrombosis and heat production occurs.

Severe injury occurs rapidly after alkaline ingestion, within minutes of contact. The most severely injured tissues are those that first contact the alkali, which is the squamous epithelial cells of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, and esophagus. The esophagus is the most commonly involved organ, with the stomach much less frequently involved after alkaline ingestions. Tissue edema occurs immediately, may persist for 48 hours, and may eventually progress sufficiently to create airway obstruction. Over time, if the injury was severe enough, granulation tissue starts to replace necrotic tissue.

Over the subsequent 2-4 weeks, any scar tissue formed initially remodels and may thicken and contract enough to form strictures. The likelihood of stricture formation primarily depends upon burn depth. Superficial burns result in strictures in fewer than 1% of cases, whereas full-thickness burns result in strictures in nearly 100% of cases. The most severe burns also may be associated with esophageal perforation.

Acid ingestions

Acid ingestions cause tissue injury by coagulation necrosis, which causes desiccation or denaturation of superficial tissue proteins, often resulting in the formation of an eschar or coagulum. This eschar may protect the underlying tissue from further damage. Unlike alkali ingestions, the stomach is the most commonly involved organ following an acid ingestion. This may due to some natural protection of the esophageal squamous epithelium. Small bowel exposure also occurs in about 20% of cases. Emesis may be induced by pyloric and antral spasm.

The eschar sloughs in 3-4 days and granulation tissue fills the defect. Perforation may occur at this time. A gastric outlet obstruction may develop as the scar tissue contracts over a 2- to 4-week period. Acute complications include gastric and intestinal perforation and upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

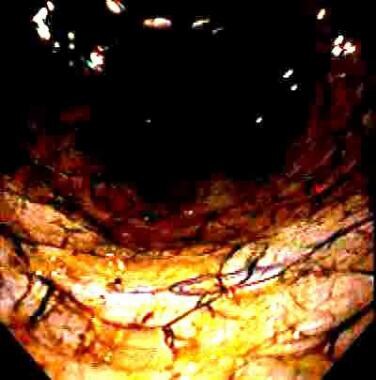

Endoscopic view of the esophagus after ingestion of an acid is shown in the images below.

Caustic ingestions. Endoscopic view of the esophagus in a patient who ingested hydrochloric acid (Lime-a-way). Note the extensive thrombosis of the esophageal submucosal vessels giving the appearance similar to chicken wire. Courtesy of Ferdinando L Mirarchi, DO, Fred P Harchelroad, Jr, MD, Sangeeta Gulati, MD, and George J Brodmerkel, Jr, MD.

Caustic ingestions. Endoscopic view of the esophagus in a patient who ingested hydrochloric acid (Lime-a-way). Note the appearance of the thrombosed esophageal submucosal vessels giving the appearance of chicken wire. Courtesy of Ferdinando L Mirarchi, DO, Fred P Harchelroad, Jr, MD, Sangeeta Gulati, MD, and George J Brodmerkel, Jr, MD.

Caustic ingestions. Endoscopic view of the esophagus in a patient who ingested hydrochloric acid (Lime-a-way). Note the extensive burn and thrombosis of the submucosal esophageal vessels, which gives the appearance of chicken wire. Courtesy of Ferdinando L Mirarchi, DO, Fred P Harchelroad, Jr, MD, Sangeeta Gulati, MD, and George J Brodmerkel, Jr, MD.

Significant exposures may also result in gastrointestinal absorption of the acidic substances leading to significant metabolic acidosis, hemolysis, acute kidney injury, and death.

Etiology

Common acid-containing sources include the following:

- Toilet bowl–cleaning products

- Automotive battery liquid

- Rust-removal products

- Metal-cleaning products

- Cement-cleaning products

- Drain-cleaning products

- Soldering flux containing zinc chloride

Common alkaline-containing sources include the following:

- Drain-cleaning products

- Ammonia-containing products

- Oven-cleaning products

- Swimming pool–cleaning products

- Automatic dishwasher detergent

- Hair relaxers

- Urinary glucose testing (Clinitest) tablets

- Bleaches

- Cement

Epidemiology

Cleaning substances, many of which contain potentially caustic agents, account for over 200,000 exposures per year reported to US poison control centers and represent the second most frequent category of exposure. [2, 3]

Approximately 80% of caustic ingestions occur in children younger than 5 years. Liquid ingestions can be quite serious. Critical solid ingestions are rare, because children generally do not swallow the burning particles that adhere to their oropharynx, but disk batteries and detergent pods are exposures that deserve particular attention in pediatric patients. [4, 5]

Most intentional ingestions occur in adults. Adult exposures have greater morbidity than childhood exposures because of the often higher volume of the exposure and the presence of possible co-ingestants. Occupational exposures often are more severe than other exposures because industrial products are more concentrated than those found in the home. [6]

Prognosis

As with all potential toxicants, the prognosis is a function of substance potency and exposure duration. Characteristics that increase the potential toxicity of these substances are the pH, the volume, and concentration of the agent; its ability to penetrate tissues; and its titratable reserve. The titratable reserve is a term that reflects the amount tissue required to neutralize a given amount of agent. Some substances are deadly even with small exposures, such as hydrofluoric acid. Some substances are relatively tolerable despite larger exposures, such as household vinegar.

Adults with psychiatric comorbidities have poorer prognosis. A retrospective study of 839 adults treated for caustic ingestion injuries treated at a single hospital reported that those with confirmed psychiatric diagnoses had a predicted 5-year survival of < 50%. [7]

Patient Education

Caustic agents should be stored in their original child-resistant containers. Many accidental childhood ingestions occur as a result of caustic substances being placed in easily accessed containers, such as milk cartons or soda bottles.

The reduced concentration of household products compared with their industrial strength counterparts has also been helpful in mitigating the severity of childhood exposures to agents such as household cleaners.

For patient education information, see What Are Common Causes of Poisoning in Children? and Battery Ingestion Treatment.

- Chirica M, Bonavina L, Kelly MD, Sarfati E, Cattan P. Caustic ingestion. Lancet. 2017 May 20. 389 (10083):2041-2052. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, Spyker DA, Rivers LJ, Feldman R, et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System(®) (NPDS) from America's Poison Centers(®): 40th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023 Oct. 61 (10):717-939. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kurowski JA, Kay M. Caustic Ingestions and Foreign Bodies Ingestions in Pediatric Patients. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun. 64 (3):507-524. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Denney W, Ahmad N, Dillard B, Nowicki MJ. Children will eat the strangest things: a 10-year retrospective analysis of foreign body and caustic ingestions from a single academic center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012 Aug. 28(8):731-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Arnold M, Numanoglu A. Caustic ingestion in children-A review. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017 Apr. 26 (2):95-104. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang JM, Liu NJ, Pai BC, Liu YH, Tsai MH, Lee CS, et al. The role of age in predicting the outcome of caustic ingestion in adults: a retrospective analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011 Jun 14. 11:72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chen YJ, Seak CJ, Chen CC, Chen TH, Kang SC, Ng CJ, et al. The Association Between Caustic Ingestion and Psychiatric Comorbidity Based on 396 Adults Within 20 Years. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020. 13:1815-1824. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Rollin M, Jaulim A, Vaz F, Sandhu G, Wood S, Birchall M, et al. Caustic ingestion injury of the upper aerodigestive tract in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015 May. 97 (4):304-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Riffat F, Cheng A. Pediatric caustic ingestion: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2009. 22(1):89-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bruzzi M, Chirica M, Resche-Rigon M, Corte H, Voron T, Sarfati E, et al. Emergency Computed Tomography Predicts Caustic Esophageal Stricture Formation. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar 12. 22 (10):1659-1664. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lurie Y, Slotky M, Fischer D, Shreter R, Bentur Y. The role of chest and abdominal computed tomography in assessing the severity of acute corrosive ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013 Nov. 51(9):834-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoffman RS, Burns MM, Gosselin S. Ingestion of Caustic Substances. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30. 382(18):1739-1748. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Mehta S, Mehta SK. The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in the management of corrosive ingestion and modified endoscopic classification of burns. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991 Mar-Apr. 37 (2):165-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bird JH, Kumar S, Paul C, Ramsden JD. Controversies in the management of caustic ingestion injury: an evidence-based review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017 Jun. 42 (3):701-708. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Arnold M, Numanoglu A. Caustic ingestion in children-A review. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017 Apr. 26 (2):95-104. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Contini S, Scarpignato C. Caustic injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Jul 7. 19 (25):3918-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Bird JH, Kumar S, Paul C, Ramsden JD. Controversies in the management of caustic ingestion injury: an evidence-based review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017 Jun. 42 (3):701-708. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tosca J, Sánchez A, Sanahuja A, Villagrasa R, Poyatos P, Mas P, et al. Caustic Ingestion: A Risk-Based Algorithm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Oct 1. 117 (10):1593-1604. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Anderson KD, Rouse TM, Randolph JG. A controlled trial of corticosteroids in children with corrosive injury of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1990 Sep 6. 323(10):637-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fulton JA, Hoffman RS. Steroids in second degree caustic burns of the esophagus: a systematic pooled analysis of fifty years of human data: 1956-2006. Clin Toxicol. 2007 May. 45(4):402-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Katibe R, Abdelgadir I, McGrogan P, Akobeng AK. Corticosteroids for Preventing Caustic Esophageal Strictures: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Jun. 66 (6):898-902. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Usta M, et al. High doses of methylprednisolone in the management of caustic esophageal burns. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun. 133(6):E1518-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Tringali A, Thomson M, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Guideline Executive summary. Endoscopy. 2017 Jan. 49 (1):83-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sawires H, Aeskander A, El-Sayed M, Marei M, Tarek S. Early topical mitomycin-C prevents stricture formation in children with caustic ingestion. J Paediatr Child Health. 2024 Jun 14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Akhijahani RF, Farahmand F, Rahmani P, Motamed F, Eftekhari K, da Silva Magalhães EI, et al. Effectiveness of sucralfate in preventing esophageal stricture in children after ingestion of caustic agents. Eur J Pediatr. 2023 Jun. 182 (6):2591-2596. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Uygun I, Arslan MS, Aydogdu B, Okur MH, Otcu S. Fluoroscopic balloon dilatation for caustic esophageal stricture in children: an 8-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Nov. 48(11):2230-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Chirica M, Kelly MD, Siboni S, et al. Esophageal emergencies: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2019. 14:26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kamijo Y, Kondo I, Watanabe M, Kan'o T, Ide A, Soma K. Gastric stenosis in severe corrosive gastritis: prognostic evaluation by endoscopic ultrasonography. Clin Toxicol. 2007. 45(3):284-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoffman RS, Burns MM, Gosselin S. Ingestion of Caustic Substances. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30. 382 (18):1739-1748. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Derrick Lung, MD, MPH, FACEP, FACMT Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Mateo Medical Center

Derrick Lung, MD, MPH, FACEP, FACMT is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Medical Toxicology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Specialty Editor Board

John T VanDeVoort, PharmD Regional Director of Pharmacy, Sacred Heart and St Joseph's Hospitals

John T VanDeVoort, PharmD is a member of the following medical societies: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Additional Contributors

Lance W Kreplick, MD, FAAEM, MMM, UHM Staff Physician, Teladoc Health; President and Chief Executive Officer, QED Medical Solutions, LLC

Lance W Kreplick, MD, FAAEM, MMM, UHM is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American Association for Physician Leadership

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.