Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vectors Efficiently Transduce Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells (original) (raw)

Abstract

Lentiviruses are potentially advantageous compared to oncoretroviruses as gene transfer agents because they can infect nondividing cells. We demonstrate here that human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-based vectors were highly efficient in transducing purified human hematopoietic stem cells. Transduction rates, measured by marker gene expression or by PCR of the integrated provirus, exceeded 50%, and transduction appeared to be independent of mitosis. Derivatives of HIV-1 were constructed to optimize the vector, and a deletion of most of Vif and Vpr was required to ensure the long-term persistence of transduced cells with relatively stable expression of the marker gene product. These results extend the utility of this lentivirus vector system.

Gene therapy of many of the most important therapeutic targets will require transduction of nondividing cell types, including hematopoietic progenitors. Most retroviruses, including murine leukemia virus (MuLV), cannot complete a replicative cycle in nondividing cells because the preintegration complex is unable to traverse the intact nuclear membrane (23, 35). However, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) has at least two gene products which allow nuclear entry in resting cells. The first is matrix (MA), which is located at the N terminus of Gag and has a canonical nuclear localization signal; in the absence of Vpr, it is required for efficient replication of HIV in primary human macrophages (2, 10, 11, 43). MA has been shown to interact biochemically with alpha-importin (karyopherin-α1), which may be partly responsible for docking the preintegration complex at the nuclear pore (9). The second gene product is Vpr, which has alpha-helices which are required for nuclear localization, and in the absence of MA it is sufficient for HIV replication in primary cells (16). Because of this property of HIV-1 (and presumably of the related lentiviruses such as simian immunodeficiency virus [SIV] and HIV-2), HIV-1 vectors have been used to transduce human cells. Akkina et al. used a replication-defective HIV pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV G) protein to transduce CD34+ cells (1). However, they did not determine the precise transduction rate or examine the expression of the marker on a per-cell basis. Reiser et al. used a similar vector to transduce CD34+ cells but did not investigate the stability of expression (34). Neither group attempted to optimize the HIV vector. Naldini et al. demonstrated that an HIV vector containing long terminal repeats (LTRs), packaging signal, marker gene, and Rev response-element could transduce resting cells (29). The HIV(VSV G) pseudotyped viral supernatant had no detectable replication-competent virus. HIV-packaging cell lines have been derived by using HIV envelope glycoprotein such that the resulting replication-defective virus had limited tropism and relatively low titer (5).

We show here that HIV(VSV G) pseudotyped viral preparations are highly efficient in transducing human CD34+ Thy1+ cells. When concentrated virus was used, the transduction rates were greater than 50% as measured by the expression of the alkaline phosphatase (AP) marker gene and close to 100% as measured by PCR of hematopoietic colonies. Transduction was dependent upon both reverse transcriptase and integrase. Transduction was optimal if the cells were exposed to cytokines for at least 48 h, but by several different criteria transduction appeared to be independent of mitosis. A series of HIV vectors were constructed, and long-term expression was greatest when there was a deletion in both Vif and Vpr in addition to Nef, Env, and Vpu. No replication-competent virus was detected in 108 infectious units. These results thus extend the utility of this lentivirus gene transfer system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC).

Healthy human donors were primed with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for 5 days and subsequently underwent leukophoresis. Peripheral blood CD34+ cells were positively selected with a cell separation device (Baxter HealthCare). CD34+ Thy1+ cells were prepared by high-speed flow cytometry as described previously (37). Purified cells were frozen in 90% fetal calf serum–10% dimethyl sulfoxide or used within 24 h of isolation. The cells were typically maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 U of penicillin G per ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin sulfate per ml and containing 20 ng of interleukin-6 (IL-6) per ml, 20 ng of IL-3 per ml, and 100 ng of stem cell factor per ml. For clonogenic assays, the cells were placed into methylcellulose (Stem Cell Technologies) in the complete medium described above along with 2 U of erythropoietin per ml and 1 ng of granulocyte-macrophage (GM)-CSF per ml.

Plasmid vector construction.

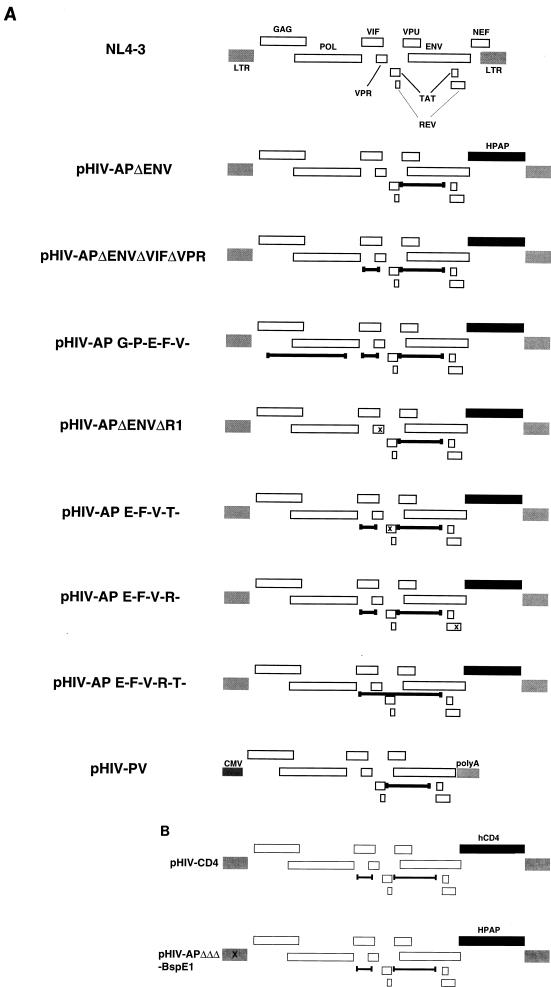

pHIV-AP was obtained from N. Landau (15). It is derived from the HIV-1 NL4-3 isolate and has a frameshift in gp160, and human placental alkaline phosphatase replaces Nef. pHIV-APΔenv was derived from pHIV-AP by deleting an _Afl_III fragment from nucleotides 6054 to 7488 (Fig. 1A). pHIV-APΔenvΔR1 was derived from pHIV-APΔenv by inserting 4 bp at the unique _Eco_RI site within Vpr at position 5743 with the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase. pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr was derived from pHIV-APΔenv by deleting the fragment from _Nde_I (position 5123, within Vif) to _Eco_RI (position 5743). pHIV-AP G-P-E-F-V- was derived from pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr by deleting the _Nsi_I fragment (positions 1251 to 4381), which encompasses Gag-Pol. pHIV-AP E-F-V-T- was derived from pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr by inserting 4 bp at the _Mfe_I site at position 5898, within the first exon of Tat. pHIV-AP E-F-V-R- was made by inserting 4 bp at the _Bam_HI site (position 8465, within the second exon of Rev) of pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr. pHIV-AP E-F-V-R-T- was derived from pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr by deleting the sequence between the _Nde_I site (position 5123) and the _Afl_III site (position 7488). pHIV-PV was constructed in pCI (Promega Biotec) by using the NL4-3 fragment from _Bss_HII (position 711) to _Xho_I (position 8887). A schematic of these HIV vectors is shown in Fig. 1A. pHIV-CD4 was constructed by replacing the _Not_I-_Xho_I fragment (which encompasses AP) of pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr with the 1.4-kb _Bam_HI fragment encoding human CD4 of pBABEneoCD4 (a gift of J. Skowronski). pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspEI was made by inserting 4 bp at the _Bsp_EI site at position 308 of pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr. These are shown in Fig. 1B. pHIV-APΔenv D64V was constructed by replacing the 3.1-kb _Apa_I-_Sal_I fragment of pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr with the 3.8-kb _Apa_I-_Sal_I fragment of pHIV-hygro D64V (a gift of A. Leavitt). pME VSV G, encoding the VSV G glycoprotein, and pSV A-Mo-MLV, encoding the MuLV amphotropic envelope, were gifts of K. Maruyama (DNAX) and D. Littman (New York University School of Medicine), respectively.

FIG. 1.

(A) HIV vector constructs. The parent construct was HIV-AP (reference 15 and data not shown), which is based upon NL4-3 (top). Deletions are indicated by delimited bars, and each frameshift mutation is indicated by x. In pHIV-PV, CMV designates the immediate-early cytomegalovirus promoter and polyA represents a cellular polyadenylation addition site. Genes are not precisely to scale. (B) HIV vectors with the 5′ LTR _Bsp_EI site removed (for PCR analysis) and with the marker human CD4 (for FACS analysis). See the text for details.

Preparation of vector supernatants.

Pseudotyped HIV supernatants were made essentially as described previously, without the addition of pcRev or butyrate (40). In brief, 293T cells were transfected with up to three plasmids by calcium phosphate coprecipitation. Supernatants were collected roughly 60 h later, centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min, and subjected to titer determination with HOS cells by endpoint dilution. Before transduction of HSC, previously frozen viral stocks were concentrated 10-fold by ultrafiltration with Amicon Centriprep-10 units as specified by the manufacturer. Alternatively, supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation with an SW28 rotor at 23,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 h and resuspended in 1/100 volume of IMDM by end-over-end rotation at room temperature (RT) for 3 to 6 h.

Flow cytometry and marker analysis.

Cells transduced with HIV-CD4 were pelleted by microcentrifugation for 5 s and incubated for 1 h in 1:10 anti-CD4–phycoerythrin (PE) (Pharmingen) in phosphate-buffered saline–2% fetal calf serum. For DNA content measurements, washed cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of 0.75 mM Hoechst dye 33342 (Molecular Probes). To simultaneously measure the transduction efficiency and the number of S-phase cells by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation, treated cells were fixed with 0.3% formaldehyde–0.4% glutaraldehyde for 5 min at RT, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and incubated for 1 h in anti-BrdU (Amersham) in the presence of 0.01% Tween 20 followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (FITC-IgG) (Sigma) for 1 h. Washed cells were incubated with anti-CD4–PE as described above. Analyses were carried out on a FACStar equipped with a UV laser for DNA content measurements or on a FACScan with Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson). For alkaline phosphatase staining, the cells were fixed as described above, heated at 65°C for 20 min, and incubated with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) along with 0.24 mg of levamisole per ml as described previously, usually for less than 2 h at RT (15). Alternatively, Vector Red (Vector Labs) replaced BCIP/NBT. The capsid antigen concentration in viral supernatants was measured with commercial reagents (Coulter).

PCR marking.

Individual hematopoietic colonies were placed in 50 μl of 0.1 M KCl–10 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.3)–2.5 mM MgCl2–0.5% Tween 20–0.5% Nonidet P-40–100 μg of proteinase K per ml and incubated overnight at 37°C. The forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers for the HIV provirus were 5′-AAGAGGCCAAATAAGGAGAGAAGAACAG-3′ (NL43-171U; positions 171 to 198) and 5′-ATCTAATTCTCCCCGCTTAATACCGAC-3′ (NL43-831L; positions 804 to 831), respectively, which gave rise to a 660-bp product. PCR was performed for 40 cycles at a denaturing temperature of 94°C for 30 s, an annealing temperature of 62°C for 1 min, and an extension temperature of 72°C for 1 min. The primers for β-globin were 5′-ACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGC-3′ and 5′-CAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC-3′ and gave rise to a 112-bp product. PCR for this product was performed as described above, except that the annealing temperature was 53°C. Alu-PCR was performed as described previously (4), except that Taqpluslong (Stratagene) was used in the initial PCR step and the second PCR step was performed with 1% of the original product for 27 cycles. Products obtained with the HIV primers were size separated by horizontal agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred under alkaline conditions to Hybond N+ (Amersham), and probed with a 32P-labelled DNA fragment encompassing the 5′ LTR of NL4-3. Washed filters were exposed to X-ray film. For the β-globin product, samples were fractionated on a 2.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide and UV light.

RESULTS

HIV(VSV G) efficiently transduces HSC.

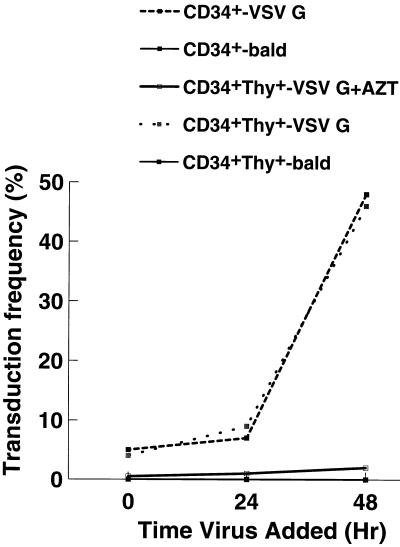

To determine the transduction rates of pseudotyped HIV vectors, an HIV provirus with a 1.45-kb deletion in gp160 and AP replacing Nef was constructed (pHIV-APΔenv; Fig. 1A). Typical endpoint titers for transiently produced pHIV-APΔenv(VSV G) were 2.0 × 107 to 3.0 × 107 IU/ml on HOS cell targets. Mobilized, peripheral blood HSC, which were either CD34+ or CD34+ Thy1+, were obtained from volunteer donors. After isolation, the cells were placed in complete medium with cytokines and transduced overnight with ultrafiltered, 10-fold-concentrated viral stocks in the presence of 4 μg of Polybrene per ml immediately (time zero) or 24 or 48 h later. Fixed cells were assayed for AP by BCIP/NBT staining 48 h after the last time point. Although transduction rates were low at 0 and 24 h (roughly 5 and 10%, respectively), they were close to 50% at 48 h, very similar for both CD34+ and CD34+ Thy1+ cells (Fig. 2). Transduction was absolutely dependent upon the presence of VSV G, and it was also dependent upon reverse transcriptase, since the addition of zidovudine inhibited transduction by more than 90%. pHIV-APΔenv(A-Mo-MLV) typically gave two- to threefold-lower transduction rates (data not shown). This may reflect the lower titer of this viral stock (which was at most 1.0 × 107 IU/ml as determined with HOS targets) or less abundant expression of the receptor for amphotropic virus envelope. To demonstrate that the expression of AP was dependent on provirus integration, an HIV construct in which one of the catalytic triad residues of IN was changed (D64V) was obtained from A. Leavitt. This virus has normal levels of reverse transcriptase activity but 1,000- to 10,000-fold-reduced titers on HOS cells (22). This mutation, when placed in the context of pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr, reduced HSC transduction rates to 1 to 2% of the control values.

FIG. 2.

Transduction increases if HSC are exposed to cytokines for 2 days. CD34+ or CD34+ Thy1+ cells were placed into cytokine-containing medium, and at 0, 24, and 48 h ultrafiltered HIV-APΔenv(VSV G) was added for an overnight incubation. For the bald virus, the VSV G expression plasmid was omitted from the original transfection. To inhibit reverse transcriptase, zidovudine (AZT) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. All cell samples were fixed at 96 h, developed with BCIP/NBT, and scored visually for a brownish-purple color change. At least 100 cells were counted for each determination.

Replication-competent virus is undetectable.

It is conceivable that a double, nonhomologous crossover event could occur during the transient transfection of the 293T cells with the VSV G envelope and replication-defective HIV provirus plasmids, resulting in replication-competent HIV with a wide host range and capable of spreading infection. To test this remote possibility, 5 × 106 HOS cells were transduced with 5.0 ml of pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr(VSV G) with a titer of 3 × 107 IU/ml such that more than 95% of the targets were transduced. A 10-ml volume of supernatant from these transduced targets was used to transduce 5 × 106 naive HOS cells, and the resulting titer was 103 IU/ml. This process was performed iteratively, and by the fourth round, the titer was undetectable. In addition, the >95% transduced HOS cells described above were serially passaged 1:4 or 1:8 every 3 to 5 days. Each week, 1 ml of supernatant was used to transduce naive HOS cells, with a resulting titer of <10 IU/ml, which did not change over a 5-week period. In addition, the few HOS cells that were transduced were passaged as described above, and the number of positively staining cells remained stable over an 8-week period. The lack of viral spread suggests that the few events observed were a result of non-envelope-mediated viral entry (i.e., endocytosis of envelope-negative, replication-defective virus).

Transduction of HSC by HIV is cell cycle independent.

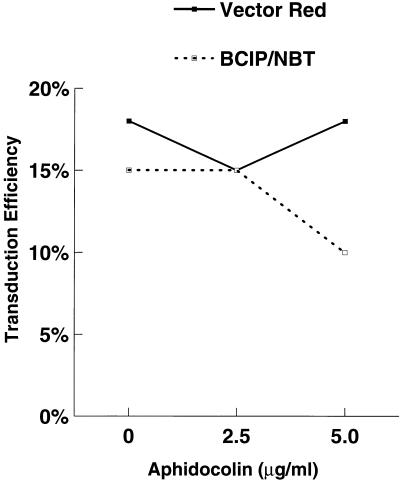

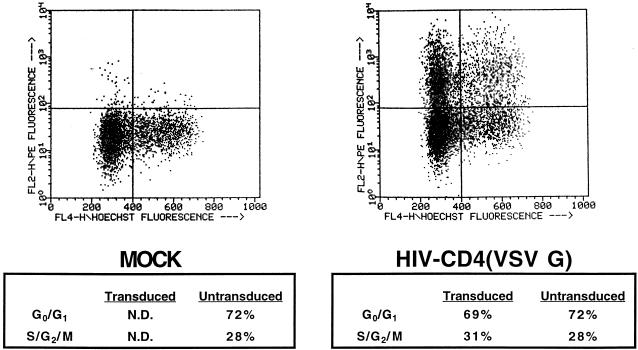

One of the principal reasons for developing lentivirus vectors is to exploit their ability to transduce nondividing targets. However, the results shown in Fig. 2 suggested that transduction may be cell cycle dependent. To address this question, purified HSC were placed in culture with cytokines and incubated 24 h later with increasing concentrations of aphidocolin (S-phase inhibitor). The cells were then transduced overnight in the presence of aphidocolin, refed, and stained for AP activity 24 h later. No clear inhibition of transduction was observed, as measured by BCIP/NBT or Vector Red staining (Fig. 3). To further explore this issue, a replication-defective HIV was constructed with CD4 as a marker for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (Fig. 1B). CD34+ cells were transduced with HIV-CD4(VSV G) overnight, and stained for DNA content with Hoechst dye 33342 and CD4 expression 48 h later. As shown in Fig. 4, the DNA content of transduced cells was almost identical to that of nontransduced cells (and the population as a whole). This is consistent with transduction being independent of the cell cycle. However, in this experiment, we could not determine the precise stage the cells were in when they were transduced. To do this, CD34+ cells were labelled with BrdU at the same time as they were transduced overnight with HIV-CD4(VSV G). At 48 h later, fixed cells were labelled with anti-BrdU and then with FITC-IgG. Washed cells were then incubated with anti-CD4–PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. The results in Fig. 5 indicate that labelling by BrdU and transduction were independent events. Similar results were obtained with a 4-h labelling-transduction period, although the proportion of the cells which were labelled or transduced was lower.

FIG. 3.

Aphidocolin does not inhibit transduction. Increasing amounts of aphidocolin (Sigma) were added to CD34+ Thy1+ cells 1 day before overnight transduction with concentrated HIV-APΔenv(VSV G) and left in the medium until fixation was carried out. Transduction was scored by BCIP/NBT or Vector Red staining as specified by the manufacturer. Vector Red caused positive cells to be bright red, and they were easily visible by light microscopy.

FIG. 4.

Transduced cells have a DNA content profile similar to that of untransduced cells. CD34+ cells were transduced overnight with ultracentrifuge-concentrated bald HIV-CD4 (left) or HIV-CD4(VSV G) (right). Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACStar equipped with a UV laser. For CD4 measurements, the primary antibody was mouse anti-CD4–PE used at a 1:10 dilution. For DNA content measurement, the cells were incubated with 0.75 mM Hoechst dye 33342 (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at 37°C. Only live cells were quantified; they were gated by exclusion of the dye propidium iodide. N.D., not determined.

FIG. 5.

Transduction is independent of the S phase. CD34+ cells were transduced overnight with ultracentrifuge-concentrated bald HIV-CD4 (mock) or HIV-CD4(VSV G) and at the same time incubated in the presence or absence of 30 μg of BrdU per ml. Two days later, the cells were fixed and incubated with mouse anti-BrdU followed by FITC-IgG. After further washing, the cells were incubated with mouse anti-CD4–PE (1:10 dilution) and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan. Similar results were obtained in a 4-h experiment. BrdU-positive cells represent those that were in the S phase.

Stable expression is dependent upon deletion of Vif and Vpr.

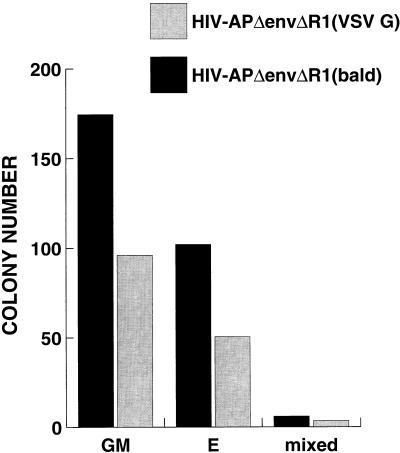

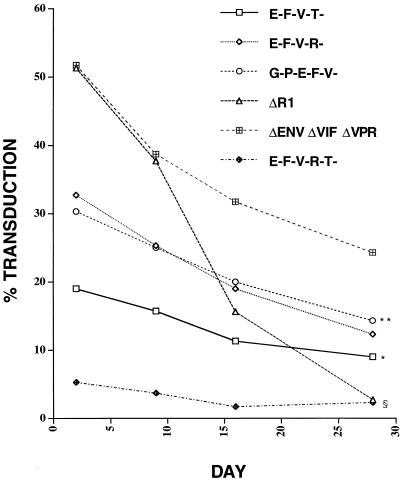

To determine the stability of expression of the introduced marker gene, CD34+ cells were transduced overnight with pHIV-APΔenvΔR1(VSV G) or bald virus. This HIV construct has a frameshift in Vpr at the _Eco_RI site and functionally behaves as a Vpr− virus in established cell lines in that transduced cells do not undergo cell cycle arrest but instead have normal growth properties. A 50% transduction rate was confirmed 48 h later, and the cells were plated into methylcellulose in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, stem cell factor, GM-CSF, and erythropoeitin to allow colony differentiation and proliferation. Two weeks later, colony types were counted and stained for AP activity. To our surprise, the cells transduced with VSV G-pseudotyped virus produced roughly 50% fewer colonies of each type than did the cells transduced with otherwise identical bald virus (Fig. 6). Very few of the colonies stained positive for AP, and those colonies were minute (fewer than 50 cells). This result, reproduced several times, suggested that there was a cytotoxic or cytostatic gene product present within pHIV-APΔenvΔR1 which did not allow for expansion of transduced cells. We then made a series of deletion and frameshift vector constructs (Fig. 1A) and tested them for initial transduction efficiency and stability of expression by bulk culture and by colony formation in methylcellulose. As shown in Table 1, each construct, pseudotyped with VSV G, had a different titer on HOS cells and a different initial transduction efficiency on CD34+ cells, with pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr being superior in this respect. AP expression was monitored in bulk culture for 4 weeks. For each of the constructs in Fig. 1A, there was a decay in the proportion of cells with detectable expression (Fig. 7). This decay was most pronounced and significant for pHIV-APΔenvΔR1 (compared to pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr), consistent with the results described above. On day 3, a fraction of the transduced cells were plated into methylcellulose and examined for AP expression after 3 weeks. The percent AP-positive colonies mirrored what was observed in bulk culture (data not shown), although there was a subpopulation of sectored colonies. These results suggest that either Vif or the amino terminus of Vpr is cytotoxic or cytostatic to CD34+ cells.

FIG. 6.

Transduction by HIV-APΔenvΔR1(VSV G) results in cytotoxicity. CD34+ Thy1+ cells were transduced overnight with ultrafiltered bald or HIV-APΔenvΔR1(VSV G). Three days later, the cells were plated into methylcellulose. Colony types and AP staining were determined 2 weeks later. GM, granulocyte-macrophage; E, erythroid; mixed, mixed cell types. Only a few AP+ colonies were observed, and these were small compared to AP− colonies. This experiment was repeated twice more with CD34+ cells, and similar results were obtained.

TABLE 1.

Titers and transduction rates of HIV vectors

| HIV vectora | Titer on HOS cells (IU/ml)b | % Transduction of CD34+ cellsc | p24 leveld | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/ml | pg/IU | |||

| HIV-AP | (1.0–2.0) × 107 | NDe | ND | ND |

| HIV-APΔenv | 2.5 × 107 | 20–48 | ND | ND |

| HIV-APΔenvΔR1 | 3.0 × 107 | 60 | 9.6 | 0.32 |

| HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr | 4.0 × 107 | 50–85 | 7.5 | 0.19 |

| HIV-AP G-P-E-F-V- | 3.0 × 106 | 35 | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| HIV-AP E-F-V-T- | 1.0 × 106 | 20 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| HIV-AP E-F-V-R- | 1.0 × 106 | 35 | 5.2 | 5.2 |

| HIV-AP E-F-V-R-T- | 5.0 × 105 | 5 | 4.7 | 9.4 |

FIG. 7.

Expression of AP marker declines over time. CD34+ cells were transduced in triplicate overnight with ultracentrifuge-concentrated VSV G pseudotyped HIV vectors (Table 1). Note that the viruses HIV-AP G-P-E-F-V-, HIV-AP E-F-V-T-, HIV-AP E-F-V-R-, and HIV-AP E-F-V-R-T- were produced by cotransfection with pHIV-PV (Fig. 1A) and pME VSV G. After transduction, the cells were either plated out into methylcellulose and 3 weeks later stained for AP with BCIP/NBT or maintained in bulk culture in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and stem cell factor and periodically stained for AP. No staining was observed for cells infected with bald HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr (data not shown). For each construct, the percentage of AP+ colonies observed in methylcellulose was similar to what was seen in bulk culture. ∗, P < 0.0001 compared to HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr; ∗∗, _P_ > 0.05 compared to HIV-AP E-F-V-R- but P < 0.0001 compared to HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr; §, P < 0.0001 for both HIV-APΔR1 and HIV-AP E-F-V-R-T- compared to HIV-APΔenvΔ VifΔ Vpr (all results obtained by two-way balanced analysis of variance). Error bars have been omitted for clarity.

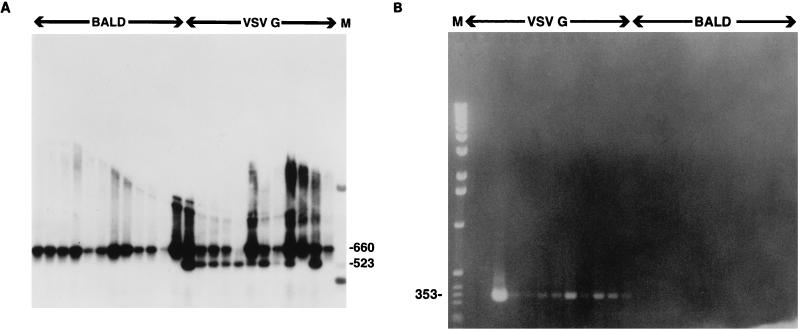

Because we could not distinguish decay in the expression of the marker gene from a defect in survival expansion of the transduced cells, we wished to determine the transduction rate by PCR marking. Because we had great difficulty in removing all contaminating DNA from the original transfection of the 293T producers, we eliminated the _Bsp_EI site in the 5′ LTR (pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspEI [Fig. 1B]). Using PCR primers which flank this site, we would thus be able to differentiate between contaminating DNA and complete proviral replication by measuring the susceptibility of the PCR product to _Bsp_EI digestion. CD34+ cells were transduced with either pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔ Vpr-BspEI(VSV G) or pHIV-APΔ envΔ VifΔ Vpr-BspE1(bald), treated with DNase I to remove most of the contaminating DNA from the original transfection, and plated into methylcellulose. In this experiment, the initial transduction rate was 42%. At 3 weeks, 24% of the colonies stained positive for AP activity. At the same time, individual colonies were picked and PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The PCR products were then digested with _Bsp_EI. As shown in Fig. 8A, the transduction rate (as measured by PCR) for pHIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspEI(VSV G) was 91% (10 of 11), since all but one of the samples which were positive for the β-globin product were also positive for the HIV product. All other colonies were positive for the control β-globin product (data not shown). In a second experiment, the PCR marking rate was 100% (12 of 12). No attempt was made to determine the copy number per colony. To show that the provirus had integrated, nested Alu-PCR was performed with the DNA from these colonies. This technique relies on the fact that in most cases there will be an Alu repeat relatively close to the integrated provirus. Nested primers present within the LTR are then used to amplify a product of a specific size (4). As shown in Fig. 8B, DNA from 10 of 12 colonies gave a product of the expected size, as visualized by ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel. This suggests that in this clonogenic assay, expression of the transgene carried by the integrated HIV provirus in a majority of the transduced cells had been suppressed to a level below the limit of detection.

FIG. 8.

PCR assays for vector proviruses in MC colonies. CD34+ cells were transduced overnight with ultracentrifuge-concentrated HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspE1(VSV G) or the bald control virus stock, treated with DNase 1 at 100 μg/ml in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 for 24 h, and then plated into methylcellulose. (A) Colonies contain fully replicated forms of HIV provirus. In this experiment, 42% of the cells initially stained positive for AP. Three weeks later, DNA was prepared from individual colonies and PCRs were carried out with primers NL43-171U and NL43-831L as described in Materials and Methods. At that time, only 24% of the colonies stained positive for AP. A portion of each PCR product was digested with _Bsp_EI, size fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel, transferred to Hybond N+ (Amersham), and hybridized to a 32P-labelled DNA probe encompassing the HIV-1 LTR. The filter was washed with 0.2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C for a total of 30 min and exposed to X-ray film for 20 min. First 12 lanes, bald virus; last 12 lanes, HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspE1(VSV G). The expected product size prior to _Bsp_EI digestion is 660 bp; after digestion, it is 523 bp. None of the first 12 and 10 of the last 12 reactions were judged to be positive. When β-globin control primers were used, only one sample was negative. (B) Colonies contain integrated forms of HIV provirus. In this experiment, the initial transduction rate was 65% and at 3 weeks 24% of the colonies stained positive for AP. DNA was prepared from individual colonies, and all 24 were positive when the β-globin control primers were used. None of the mock-transduced and all 12 of the HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspE1(VSV G)-transduced colonies were positive by PCR with the primers used in panel A. Samples were then subjected to Alu-PCR as described previously (4), and the products were size fractionated on a 1.5% agarose gel prestained with ethidium bromide. None of the mock-transduced and 10 of 12 HIV-APΔenvΔVifΔVpr-BspE1(VSV G)-transduced colonies gave the expected size of product, as indicated.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate efficient transduction of purified human HSC by HIV vectors pseudotyped with VSV G. Titers of transiently produced pseudotyped HIV reported here are equivalent to or greater than those previously reported (1, 28, 29, 34), which may reflect the nature of the enzymatic marker AP. In studies with CD34+ cells, the HIV proviral construct simply had a deletion in Env, with the marker gene inserted within Env or Nef, and the stability of marker gene expression was not examined. In the results reported here, since more of the HIV genome was deleted from the vector, the titer was reduced accordingly, which may be due in part to inefficient cotransfection of the 293T producer cells, with the plasmid providing complementing functions in trans. Alternatively, packaging or reverse transcription of deleted vectors may not be optimal. The transduction rates we observed for HSC exceeded those of other currently used retroviruses (6, 12, 20, 21, 27) and were roughly equivalent to those of other viral vector systems in use (3, 7, 13, 26, 30, 45). These are likely to be true transduction rates, since they were dependent upon both reverse transcriptase and integrase. We were surprised that the titers of the Tat− HIV construct (pHIV-AP E-F-V-T-) were reduced 30- to 50-fold on HOS cell targets whereas CD34+ transduction rates were diminished only 2- to 3-fold. The Tat− virus was prepared by cotransfection of the pHIV-PV construct, which has an intact Tat gene, so that production of the virus would presumably not be limiting. It is possible that the AP assay is more sensitive and nonlinear than measurements of transcript abundance. Readthrough transcription from bona fide or fortuitous promoters in cellular flanking sequences followed by conventional splicing would also yield an AP-positive cell. The titers of the construct lacking functional Tat and Rev were reduced 100-fold on HOS cells and gave very poor transduction rates on HSC.

The transduction rates in our experiments were reproducibly higher if HSC were preactivated with cytokines for 48 h. However, this high transduction rate was independent of mitosis in that aphidocolin, an S-phase inhibitor, had no consistent effect on the transduction efficiency. In addition, transduced cells had nearly the same DNA content profile as untransduced cells, with an insignificant bias toward the S, G2, and M phases. Furthermore, transduction by HIV(VSV G) was independent of the S phase, as indicated by the BrdU labelling experiment. These results, taken together, are consistent with previous findings that HIV can infect nondividing cells. It is not clear why we observed a requirement for the cells to be cultured in the presence of cytokines for a few days for maximal transduction rates, which is at odds with the results discussed above (34). However, the CD34+ cells were prepared and transduced in a slightly dissimilar manner, and different markers and detection systems were used. More than 99% of freshly isolated HSC are in the G0/G1 (presumably G0) phase as measured by DNA content analysis (34, 42). HSC require cytokines both to prevent apoptosis and to enter G1. The results presented here may be reconciled with the findings that efficient, complete transduction by HIV probably requires the target cell to be transcriptionally active and at least in G1 (out of G0) (38, 39, 41). HIV can enter G0 CD4+ T cells and macrophages, but reverse transcription and expression of viral gene products are limited (41, 47). Importantly, these cells need not traverse mitosis for nuclear entry and expression of viral genes to take place. Thus, if transduction is measured by transgene expression (as it was in most cases here), a requirement for an activated state and consequent transcription but not mitosis is observed.

We also demonstrate that expression of the transgene wanes over the course of several weeks, so that an initial transduction rate measured by expression of more than 50% (as an example) declines to a proportion of 25% at 3 weeks. It is not known whether expression diminishes further over more extended times. However, transduction measured by PCR marking remained high. It is uncertain which features of the virus (or host cell) cause extinction of viral gene expression, but this phenomenon is generally observed for the retroviruses and remains problematic for their use as gene transfer agents. An unexpected finding presented here is that HIV-1 contains a gene product which is selectively cytotoxic to HSC. This product is not Tat or the carboxy terminus of Vpr, which have been shown in other cell types to cause apoptosis (24, 32, 46) and G2/M arrest (14, 17, 25, 33), respectively. Based on the series of deletion constructs, the cytotoxic product is either Vif or the amino terminus of Vpr. Other experiments suggest that this property maps within Vif, not Vpr (data not shown). Although Vif is highly conserved among different HIV-1 isolates and is present in other lentiviruses, its role in the viral life cycle remains poorly defined. Vif is required for viral replication in primary cell types and is critical for proviral DNA synthesis in selected target cells (44). The cytotoxicity of certain HIV-1 isolates has been mapped to the Vif gene product (36), with the cytopathic effect being manifested as loss of cell viability and giant cell formation. Others have reported that cell clones that survive the initial cytopathic effect harbor HIV species which have individual mutations in accessory gene products, including Vif (18, 19). However, toxic effects of Vif are not consistently seen (44), and we do not observe the cytotoxic effect of Vif in established human and mouse cell lines. For the HSC transduced with Vif+ HIV, multinucleated giant cells were not observed, but we do not yet know the cause of the loss of cell viability. These results do suggest, however, that deletion of Vif is a requisite for maintenance of the transduced HSC population and hence for expression of the transgene.

We have yet to detect replication-competent virus present in the transient-transfection viral supernatants. This has also been true for similar HIV vector systems, which have larger deletions of the provirus (5, 28, 29, 31). It remains possible that replication-competent virus exists at a level of 10−9 or 10−10 (representing 30 or 300 ml of viral supernatant, respectively) and that the assay used here is not sensitive enough to detect these rare occurrences. It is also conceivable that a target cell could express an endogenous envelope so that cells transduced with pHIV-APΔenv would produce virus of altered tropism but would still be replication defective. It is thus most desirable to use a vector such as pHIV-AP G-P-E-F-V- or the previously described transfer vector (29), which has a minimum of residual HIV sequence. Packaging cell lines with HIV core proteins and HIV envelopes have been described, but the host range of the replication-defective virus was more restricted and the titers were reduced at least 1,000-fold compared to HIV(VSV G) pseudotypes (5, 31). Transient production of viral supernatants is clearly advantageous for vector development, but it will be desirable ultimately to generate suitable HIV packaging cell lines of wide host range in a bioreactor system, as has been demonstrated for MuLV (8).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Leavitt, N. Landau, and D. Littman for generous gifts of reagents; R. Pillai and other members of the Brown laboratory for helpful discussions; C. Dowding for purified HSC; M. Reitsma for FACS analysis; and R. Tushinski for advice on HSC culture and assay reagents.

H.T.M.W. was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) summer undergraduate fellowship program sponsored by Stanford University; R.E.S. was a Pfizer postdoctoral scholar and was supported by NIH grant CA71671. P.O.B. is an investigator of the HHMI. This work was funded in part by NIH grant AI36898.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akkina R H, Walton R M, Chen M L, Li Q-X, Planelles V, Chen I S Y. High-efficiency gene transfer into CD34+ cells with a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based retroviral vector pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein G. J Virol. 1996;70:2581–2585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2581-2585.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukrinsky M I, Haggerty S, Dempsey M P, Sharova N, Adzhubel A, Spitz L, Lewis P, Goldfarb D, Emerman M, Stevenson M. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature. 1993;365:666–669. doi: 10.1038/365666a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee S, Lu D, Podsakoff G, Wong K K. Strategies for efficient gene transfer into hematopoietic cells: the use of adeno-associated virus vectors in gene therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;770:79–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb31045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun T-W, Stuyver L, Mizell S B, Ehler L A, Mican J M, Baseler M, Lloyd A L, Nowak M A, Fauci A S. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13193–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corbeau P, Kraus G, Wong-Staal F. Efficient gene transfer by a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-derived vector utilizing a stable HIV packaging cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14070–14075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cournoyer D, Caskey C T. Gene therapy of the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:297–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunbar C E, Emmons R V. Gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells: progress and problems. Stem Cells. 1994;12:563–576. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forestell S P, Bohnlein E, Rigg R J. Retroviral end-point titer is not predictive of gene transfer efficiency: implications for vector production. Gene Ther. 1995;2:723–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallay P, Stitt V, Mundy C, Oettinger M, Trono D. Role of the karyopherin pathway in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nuclear import. J Virol. 1996;70:1027–1032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1027-1032.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallay P, Swingler S, Aiken C, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of non-dividing cells: C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation of the viral matrix protein is a key regulator. Cell. 1995;80:379–388. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallay P, Swingler S, Song J, Bushman F, Trono D. HIV nuclear import is governed by the phosphotyrosine-mediated binding of Matrix to the core domain of integrase. Cell. 1995;83:569–575. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilboa E. Retroviral gene transfer: applications to human therapy. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;352:301–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman S, Xiao X, Donahue R E, Moulton A, Miller J, Walsh C, Young N S, Samulski R J, Nienhuis A W. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1994;84:1492–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He J, Choe S, Walker R, Marzio P, Morgan D O, Landau N R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He J, Landau N R. Use of a novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reporter virus expressing human placental alkaline phosphatase to detect an alternative viral receptor. J Virol. 1995;69:4587–4592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4587-4592.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinzinger N K, Bukinsky M I, Haggerty S A, Ragland A M, Kewalramani V, Lee M A, Gendelman H E, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jowett J B M, Planelles V, Poon B, Shah N P, Chen M-L, Chen I S Y. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene arrests infected T cells in the G2 + M phase of the cell cycle. J Virol. 1995;69:6304–6313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6304-6313.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kishi M, Nishino Y, Sumiya M, Ohki K, Kimura T, Goto I, Nakai M, Kakinuma M, Ikuta K. Cells surviving infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: vif or vpu mutants produce non-infectious or markedly less cytopathic viruses. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:77–87. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-1-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishi M, Zheng Y-H, Bahmani M K, Tokunaga K, Takahashi H, Kakinuma M, Lai P K, Nonoyama M, Luftig R B, Ikuta K. Naturally occurring accessory gene mutations lead to persistent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of CD4-positive T cells. J Virol. 1995;69:7507–7518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7507-7518.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohn D B. The current status of gene therapy using hematopoietic stem cells. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1995;7:56–63. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199502000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohn D B. Gene therapy for hematopoietic and lymphoid disorders. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leavitt A D, Robles G, Alesandro N, Varmus H E. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutants retain in vitro integrase activity yet fail to integrate viral DNA efficiently during infection. J Virol. 1996;70:721–728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.721-728.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis P F, Emerman M. Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994;68:510–516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.510-516.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C J, Friedman D J, Wang C, Metelev V, Pardee A B. Induction of apoptosis in uninfected lymphocytes by HIV-1 Tat protein. Science. 1995;268:429–431. doi: 10.1126/science.7716549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marzio P, Choe S, Ebright M, Knoblauch R, Landau N R. Mutational analysis of cell cycle arrest, nuclear localization, and virion packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J Virol. 1995;69:7909–7916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7909-7916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitani K, Clemens P R, Moseley A B, Caskey C T. Gene transfer therapy for heritable disease: cell and expression targeting. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1993;339:217–224. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulligan R C. The basic science of gene therapy. Science. 1993;260:926–932. doi: 10.1126/science.8493530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gage F H, Trono D, Verma I M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11382–11388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage F H, Verma I M, Trono D. In vivo delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neering S J, Hardy S F, Minamoto D, Spratt S K, Jordan C T. Transduction of primitive human hematopoeitic cells with recombinant adenovirus vectors. Blood. 1996;88:1147–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poeschla E, Corbeau P, Wong-Staal F. Development of HIV vectors for anti-HIV gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11395–11399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purvis S F, Jacobberger J W, Sramkoski R M, Patki A H, Lederman M M. HIV type 1 Tat protein induces apoptosis and death in Jurkat cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:443–450. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Re F, Braaten D, Franke E K, Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. J Virol. 1995;69:6859–6864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6859-6864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiser J, Harmison G, Kluepfel-Stahl S, Brady R O, Karlsson S, Schubert M. Transduction of nondividing cells using pseudotyped defective high-titer HIV type 1 particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15266–15271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roe T, Reynolds T C, Yu G, Brown P O. Integration of murine leukemia virus DNA depends on mitosis. EMBO J. 1993;12:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakai K, Ma X, Gordienko I, Volsky D J. Recombinational analysis of a natural noncytopathic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolate: role of the vif gene in HIV-1 infection kinetics and cytopathicity. J Virol. 1991;65:5765–5773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5765-5773.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasaki D T, Tichenar E H, Lopez F, Combs J, Uchida N, Smith C R, Stokdijk W, Vardanega M, Buckle A M, Chen B. Development of a clinically applicable high-speed flow cytometer for the isolation of transplantable human hematopoeitic stem cells. J Hematother. 1995;4:503–514. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1995.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuitemaker H, Kootstra N A, Fouchier R A M, Hooibrink B, Miedema F. Productive HIV-1 infection of macrophages restricted to the cell fraction with proliferative capacity. EMBO J. 1994;13:5929–5936. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spina C A, Guatelli J C, Richman D D. Establishment of a stable, inducible form of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA in quiescent CD4 lymphocytes in vitro. J Virol. 1995;69:2977–2988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2977-2988.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutton R E, Littman D R. Broad host range of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 demonstrated with an improved pseudotyping system. J Virol. 1996;70:7322–7326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7322-7326.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang S, Patterson B, Levy J A. Highly purified quiescent human peripheral blood CD4+ T cells are infectable by human immunodeficiency virus but do not release virus after activation. J Virol. 1995;69:5659–5665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5659-5665.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uchida N, Yang Z, Combs J, Pourquie O, Nguyen M, Ramanathan R, Fu J, Welply A, Chen S, Weddell G, et al. The characterization, molecular cloning, and expression of a novel hematopoietic cell antigen from CD34+ human bone marrow cells. Blood. 1997;89:2706–2716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Schwedler U, Kornbluth R S, Trono D. The nuclear localization signal of the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 allows the establishment of infection in macrophages and quiescent T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6992–6996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Schwedler U, Song J, Aiken C, Trono D. Vif is crucial for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis in infected cells. J Virol. 1993;67:4945–4955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4945-4955.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Kuszynski C, Ino K, Heimann D G, Shephard H M, Yasui Y, Maneval D C, Talmadge J E. Gene transfer into human bone marrow hematopoeitic cells mediated by adenovirus vectors. Blood. 1996;87:5032–5039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westendorp M O, Frank R, Ochsenbauer C, Stricker K, Dhein J, Walczak H, Debatin K, Krammer P H. Sensitization of T cells to CD95-mediated apoptosis by HIV-1 Tat and gp120. Nature. 1995;375:497–500. doi: 10.1038/375497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zack J A, Arrigo S J, Weitsman S R, Go A S, Haislip A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]