Identification of Sec36p, Sec37p, and Sec38p: Components of Yeast Complex That Contains Sec34p and Sec35p (original) (raw)

Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins Sec34p and Sec35p are components of a large cytosolic complex involved in protein transport through the secretory pathway. Characterization of a new secretion mutant led us to identify SEC36, which encodes a new component of this complex. Sec36p binds to Sec34p and Sec35p, and mutation of SEC36 disrupts the complex, as determined by gel filtration. Missense mutations of SEC36 are lethal with mutations in COPI subunits, indicating a functional connection between the Sec34p/sec35p complex and the COPI vesicle coat. Affinity purification of proteins that bind to Sec35p-myc allowed identification of two additional proteins in the complex. We call these two conserved proteins Sec37p and Sec38p. Disruption of either _SEC37_or SEC38 affects the size of the complex that contains Sec34p and Sec35p. We also examined COD4,COD5, and DOR1, three genes recently reported to encode proteins that bind to Sec35p. Each of the eight genes that encode components of the Sec34p/sec35p complex was tested for its contribution to cell growth, protein transport, and the integrity of the complex. These tests indicate two general types of subunits: Sec34p, Sec35p, Sec36p, and Sec38p seem to form the essential core of a complex to which Sec37p, Cod4p, Cod5p, and Dor1p seem to be peripherally attached.

INTRODUCTION

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, COPI and COPII vesicles shuttle proteins between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the Golgi apparatus (Kaiser et al., 1997). COPII vesicles are responsible for most, if not all, biosynthetic protein transport from the ER to the _cis_-Golgi, whereas COPI vesicles are the carriers for retrograde transport of proteins from the Golgi to the ER. Defects in either COPI or COPII vesicle transport can block ER-to-Golgi transport, possibly because some cargo may need to be retrieved from the Golgi to the ER for ER-to-Golgi transport to continue (Pelham, 1994).

The stages of COPII vesicle transport include vesicle formation, vesicle docking, and vesicle fusion. Vesicle formation occurs by recruitment of cytosolic complexes onto the ER surface, and results in the pinching off of protein-coated vesicles enriched with cargo destined for the Golgi (Barlowe, 1995). Vesicle docking takes place at the Golgi, via formation of a physical bridge involving complexes of integral membrane proteins known as soluble_N_-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) (Söllner et al., 1993). In SNARE complexes, molecules on the vesicle associate with molecules on the target membrane. Subsequent to SNARE complex formation, vesicle and Golgi membrane bilayers fuse and the cargo contained in the vesicle is delivered to the Golgi.

COPII vesicles that have been formed in vitro can attach to the Golgi even in the absence of the formation of SNARE complexes (Cao et al., 1998). This pre-SNARE complex association, called tethering, is proposed to be a primary, possibly looser, connection between vesicles and the Golgi (Pfeffer, 1999; Guo et al., 2000). A large number of proteins have been implicated in tethering COPII vesicles, by their effects on vesicle attachment in vitro. These include the multisubunit transport protein particle complex (TRAPP complex), the small GTP-binding protein Ypt1p, the large-coiled coil protein Uso1p, and a large complex containing the Sec34p and Sec35p proteins (Cao et al., 1998; Sacher et al., 1998;VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999).

Disruption of either SEC34 or SEC35 causes a severe growth defect in yeast, and Sec34p is conserved throughout eukaryotic genomes (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999; Kim_et al._, 1999; Suvorova et al., 2001). Therefore, the Sec34p/Sec35p complex is likely to have an important function in vesicle-mediated transport. This function is poorly characterized, but genetic interactions have suggested a functional connection between the Sec34p/Sec35p complex and both Ypt1p and Uso1p. For instance, the growth defects of sec34 and sec35 mutants can be suppressed by overexpression of Ypt1p or Uso1p (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999). Furthermore, defects in YPT1,USO1, SEC34, and SEC35 can all be suppressed by expression of SLY1-20, a dominant allele of_SLY1_, which encodes a regulator of SNARE complexes (Dascher_et al._, 1991; Sapperstein et al., 1996;VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999).

Interestingly, SEC34 loss of function alleles were also isolated in a screen for mutants that mislocalize late Golgi and vacuolar proteins; SEC34 is the same gene as_GRD20_ (Spelbrink and Nothwehr, 1999). At present, it is not clear how to reconcile a role for Sec34p in the late secretory pathway with its proposed role in ER-to-Golgi transport.

In both yeast and mammalian cells, Sec34p exists in a large complex (Kim et al., 1999; VanRheenen et al., 1999;Suvorova et al., 2001). Previous work suggested that the yeast Sec34p/Sec35p complex contains additional unidentified components (Kim et al., 1999). Herein, we present the identification and analysis of three new components of the yeast Sec34p/Sec35p complex, encoded by the genes SEC36, SEC37, and_SEC38_.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Tables1 and 2.

Table 1.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CKY10 | Mata ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY25 | Matα_sec3-2_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY39 | Matα_sec12-4 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY45 | Matα sec13-1 ura3-52 his4-619 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY50 | Matα sec16-2 ura3-52 his4-619 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY54 | Matα_sec17-1 ura3-52 his4-619_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY58 | Matα sec18-1 ura3-52 his4-619 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY68 | Matα sec21-1 ura3-52 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY78 | Matα_sec23-1 ura3-52 his4-619_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY80 | Matα sec22-3 ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY86 | Matα bet1-1 ura3-52 his4-619 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY88 | Matα_bet2-1 ura3-52 his4-619_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY146 | Matα sec1-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY147 | Matα sec2-41 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY149 | Matα_sec4-8 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY150 | Matα sec5-24 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY151 | Matα sec6-4 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY152 | Matα_sec8-9 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_ | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY350 | Matα ret2 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY405 | Matα sly1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory (312ts derivative) |

| CKY416 | Matα sec27-1 ura3-52 suc2Δ9 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| CKY537 | Matα sec26 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Kaiser laboratory collection |

| GWY93 | Matα_sec35-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_ | Waters laboratory collection |

| GWY95 | Mata sec34-2 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | Waters laboratory collection |

| CKY726 | Mata sec36-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | This study (271ts derivative) |

| CKY727 | Matα_sec36-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_ | This study (271ts derivative) |

| CKY728 | Mata sec6-4 sec36-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | This study |

| CKY729 | Mata sec36::TRP1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3Δ200 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1Δ63+ pRR30 | This study |

| CKY730 | Mata/α sec36::kanMX6/SEC36 ura3-52/ura3-52 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 | This study |

| CKY731 | Matα sec34-3 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | This study (394ts derivative) |

| CKY732 | Matα ypt6 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | This study (169ts derivative) |

| CKY733 | Mata_sec37::kanMX4 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_ | This study |

| CKY734 | Matα sec37::kanMX4 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 | This study |

| CKY735 | Mata_sec38::kanMX4 ura3-52 leu2-3,112_+ pSV11 | This study |

| CKY736 | Mata/α sec38::kanMX4/SEC38 ura3-52/ura3-52 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 | This study |

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Description | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pCD43 | _GAL1/GAL10_promoter vector | Shaywitz et al. (1995) |

| pET21d | E.coli His6-fusion vector | Novagen |

| pGTEP1 | 3xHA tag in BLUESCRIPTII vector (pKS+) | Tyers et al. (1993) |

| pNV31 | CEN TPI1_-promoted invertase_URA3 | H. Pelham (Medical Research Council, UK) |

| pRR4 | YCp50 library clone #18, with_Afl_II-_Afl_II deletion in YGL223c | This study |

| pRR14 | CEN SEC36 URA3 | This study |

| pRR30 | CEN_SEC36-HA URA3_ | This study |

| pRR31 | 2μ SEC36 URA3 | This study |

| pRR35 | CEN GAL1_-promoted_SEC36 | This study |

| pRR55 | His6-Sec84p | This study |

| pRR65 | 2μ_SEC34-myc LEU2_ | This study |

| pRR66 | 2μ_SEC35-myc LEU2_ | This study |

| pRR72 | 2μ SEC38 URA3 | This study |

| pRS306 | integrating vector with_URA3_ | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pRS305-2μ | 2μ vector marked with LEU2 | Gimeno et al. (1995) |

| pRS306-2μ | 2μ vector marked with URA3 | Gimeno_et al._ (1995) |

| pRS315 | CEN vector marked with_LEU2_ | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pRS316 | CEN vector marked with URA3 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pRS426 | 2μ vector marked with URA3 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pSV11 | CEN SLY1-20 URA3 | VanRheenen_et al._ (1999) |

| pSV17 | 2μ SEC35 URA3 | VanRheenen et al. (1999) |

| pSV25 | 2μ_SEC34 URA3_ | VanRheenen et al. (1999) |

Plasmid Construction and Gap Repair

To make pRR14, an EaeI/_Kpn_I fragment containing SEC36 was subcloned from a library clone into the_Not_I/_Kpn_I sites of pRS316. The same_Eae_I/_Kpn_I fragment was inserted into pRS306–2μ cut with _Not_I/_Kpn_I, resulting in pRR31. pRR35 was made in two steps. First, a _Bam_HI site was introduced in pRR14 just before the first ATG codon of SEC36 by site-directed mutagenesis, as described in Kunkel et al.(1987), by using the primer 5′-TGGTAGAAAACCTAAAAAAAACCAATACGGATCCAAATGGATGAAGTC-3′. Then, the _Bam_HI/_Kpn_I (with blunt end) fragment from this construct was ligated into the_Bam_HI/Sac_I (with blunt end) site of the_URA3 centromere vector pCD43, placing it just downstream of the GAL1 promoter.

For integrative mapping of SEC36, a 2.7-kb_Kpn_I/_Hin_dIII fragment from sequences flanking the YGL223c open reading frame (ORF) was inserted into pRS306. The resulting plasmid was cut with _Mlu_I for integration into the genome by homologous recombination.

pRR55 was made by first polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifying_SEC36_ from pRR14 by using the following primers: primer 1, 5′-AAAAAACCAATACGGATCCAAATGGATGAAGTCTTAC-3′; and primer 2, 5′-ATTATATTACTCGAGCCTTAATTGAGTAATTTGATC-3′. The resulting fragment was digested with _Bam_HI/_Ava_I and inserted into pET21d (Novagen, Madison, WI) at its_Bam_HI/_Xho_I sites.

pRR30 was made by first adding a _Not_I site at the 3′ end of the SEC36 coding region in pRR14 through site-directed mutagenesis by using the following primer: 5′-CGATCAAATTACTCAATTACGCGGCCGCTAATATAATAGCACGAGGGA-3′. The resulting plasmid was cut with _Not_I and ligated to a_Not_I fragment from pGTEP1, which contains three tandem in-frame hemagglutinin (HA) epitopes.

Plasmids pRR65 and pRR66 were made by PCR amplification of_SEC34_ and SEC35 with the following primers: SEC34 primer 1, 5′-AACTCTAAGTATCAGCTGCGGCCGCATCATAAGTAGTATTA-AT-3′; SEC34 primer 2, 5′-GAAATTACACATAAGTTTATTGCGCGCTGGTATCAATATCACC-3′; SEC35 primer 1, 5′-GGTATAATGGGATGTGCGGCCGCTTTTATGAGGGTGCCTTA-3′; and SEC35 primer 2, 5′-GAAAGTTTTCTCCCAACTGCGCGCTTTTTATAATGGAGACTA-3′. Resulting fragments were digested with _Bss_HII/_Not_I and ligated into a vector derived from pRS325 that contains a_Bss_HII fragment encoding three tandem _c-myc_epitopes. Sec34p-myc and Sec35p-myc proteins expressed from these constructs contain the following amino acid residues at the junctions with their epitope tags: Sec34p-myc, … GDIDTSAPEQKLISEEDLN… ; Sec35p-myc, … LVSIISAPEQKLISEEDLN…

To make plasmid pRR72, SEC38 was PCR amplified with the following primers: primer 1, 5′-TATAGTGAAGGATCCAAGCAACTTTTGAAACACATTTAC-3′; and primer 2, 5′-TATAGTGAAGGAGGTACCCAACTTTTGAAACACATTTAC-3′. The resulting fragment was digested with _Bam_HI and_Kpn_I and ligated into pRS426 at its_Bam_HI/Kpn_I sites. Gap repair of_sec36-1 was performed using a variant of pRR14 that was cut with _Hpa_I/_Eco_RI (Orr-Weaver et al., 1983).

Identification of sec34-3

A centromeric plasmid expressing SEC34 was constructed by ligating a _Sph_I fragment from a YCp50 library clone into the _Sma_I site of the vector pRS316. The only genes in this resulting plasmid were SEC34 and the tRNA-Glu gene. Removal of a _Bst_EII/_Bgl_II fragment internal to SEC34 abolished the ability of this construct to rescue the temperature-sensitive (ts) growth of strain 394ts. To show that the mutation in strain 394ts was at the SEC34 locus, a 2.7-kb_Xho_I/_Spe_I fragment near the SEC34 gene was ligated into pRS306, and this plasmid was cut with_Hin_dIII. This fragment was integrated by homologous recombination into the genome of a wild-type strain, which was then mated to the 394ts strain. After sporulation, 14/14 tetrads showed cosegregation of Ts+ and Ura+ phenotypes.

Gas1p, Carboxypeptidase Y (CPY), and Invertase Pulse-labeling and Immunoprecipitation

Transport assays by radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation were done as described in Gimeno et al. (1995). For Gas1p and CPY assays, radiolabeled extracts from 1 OD600 units of cells were incubated with 1 μl of either Gas1p antibody or CPY antibody. After washes, the entire immunoprecipitate was loaded onto a gel. For internal versus secreted invertase immunoprecipitations, strains with invertase expressed from the TPI promoter were used to circumvent the need to induce invertase production in low glucose. Invertase expressed in this way was transported like wild-type secreted invertase (our unpublished data). For each experiment, 2 OD600 units of cells were labeled for 10 min, and converted to spheroplasts by using lyticase. Spheroplasts were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Resulting supernatant and pellet fractions were resuspended in 1 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer before incubation with 1 μl of invertase antibody. Immunoprecipitates were then processed for SDS-PAGE as described in Gimeno et al. (1995).

Disruption of SEC36, SEC37, and SEC38

The following primers were used to amplify_kanMX6_ flanked by sequences adjacent to the YGL223c ORF, used to disrupt SEC36 by homologous recombination: primer 1, 5′-CAACAAATCTTGTGGTAGAAAACCTAAAAAAAACCAATACGATAGAAACGTACGCTGCAGGTCGAC-3′; and primer 2, 5′-CATTATCAATAAGTTTGCGAGGCGGGTACCCTCCCTGTGCTATTATAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC-3′.sec37 and sec38 null strains were obtained from EUROSCARF (www.uni-frankfurt.de/fb15). Fragments containing the disrupted loci were PCR amplified with primers to flanking sequences and transformed into the S288C genetic background to generate CKY733, CKY734, CKY735, and CKY736.

Protein Extracts and Cell Fractionation

Whole-cell extracts were prepared by resuspending 2 OD600 units of cells in 30 μl of sample buffer (60 mM Tris-Cl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 100 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10% glycerol, and 0.001% bromphenol blue), boiling for 1 min, and lysing by agitation with glass beads. An additional 70 μl of sample buffer was added before 30 μl of the supernatants was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Cell fractionation was performed as described in Espenshade et al. (1995).

Sec36p Antibody Production and Immunoblotting

Plasmid pRR55 was transformed into BL21(DE3) bacteria (Novagen). Transformants were grown overnight at 24°C in 2XYT medium with antibiotics. Induction was not necessary for fusion protein production. Cells were resuspended and sonicated. Insoluble Sec36p-His6 was pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. Guanidine was removed by dialysis, resulting in precipitation of the fusion protein. The precipitate was harvested by centrifugation and solubilized in sample buffer. Recovered protein was run out by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie stained, and used to prepare polyclonal antibodies in rabbits by standard protocols at Covance. Sec36p antibodies were affinity purified using fusion protein immobilized on nitrocellulose membranes, and eluted with 100 mM glycine, pH 2.5. Antibodies were used at the following dilutions for immunoblotting: anti-invertase at 1/1000, anti-CPY at 1/1000, anti-glutathione_S_-transferase (sc-459; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1/1000, affinity-purified anti-Sec36p at 1/500, affinity-purified anti-Sec34p at 1/1000, and affinity-purified anti-Sec35p at 1/500. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) were used at 1/3000.

Sec34p-myc, Sec35p-myc, and Sec36p Coimmunoprecipitation Experiments

Sec34p-myc and Sec35p-_myc_immunoprecipitations were done by a variation of the protocol for Sec35p-myc immunoprecipitations of Kim et al.(1999). Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.5–1.5. For each experiment, 10 OD600 units of cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in buffer D (20 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Samples were lysed with glass beads, and 850 μl of buffer D was added per tube before centrifugation for 1 min at 12,000 × g. The cleared supernatant was transferred to a 1.5-ml ultracentrifuge tube, and centrifuged for 30 min at 100,000 × g in a TLS55 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The supernatant from this centrifugation was adsorbed with protein A-Sepharose. After removal of protein A-Sepharose, the supernatant was incubated with 5 μl of c-myc antibody (9E10) overnight at 4°C. Immune complexes were collected by incubation with protein A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with buffer D and three times with buffer E (same as buffer D, but with 500 mM KCl), and then resuspended in sample buffer, before SDS-PAGE. For radiolabeled Sec36p and Sec35p-myc immunoprecipitations, 10 OD600 units of cells were first labeled for 3 h in medium lacking methionine with 200 μCi of35S Express label (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA), and then immunoprecipitations were performed as described above, with either 5 μl of affinity-purified Sec36p antibody or 5 μl of 9E10 antibody.

Partial Purification of Sec34p/Sec35p/s36p

Yeast strains were grown at room temperature to an OD600 of 3–4. Then 12,000 OD600 units of cells were collected by centrifugation, and processed similarly to methods described inVanRheenen et al. (1999), with the following modifications. The only protease inhibitor added was 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cells were resuspended in 100 ml of lysis buffer, and lysed in a bead beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Lysed sample was pelleted for 20 min at 20,000 × g in a SS34 rotor (Beckman Coulter), and the supernatant was transferred to a SW28 rotor (Beckman Coulter), where it was centrifuged for 2 h at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm syringe filter. To 36 ml of the filtrate, saturated ammonium sulfate solution was added dropwise to a final concentration of 40%. Anion exchange chromatography was performed with a 16-ml CL-6B DEAE-Sepharose column (1.5 cm i.d.; Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ). Samples were bound in buffer containing 100 mM KCl and eluted with a gradient of KCl from 100 to 400 mM. Fractions containing Sec36p-HA were identified by immunoblotting with HA antibody (12CA5). Then, 500 μl of the Sec36p-HA elution was loaded onto a 24-ml Superose 6 gel filtration column (HR10/30; Pharmacia) preequilibrated in 190 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, and 1 mM DTT. The column was run at 0.4 ml/min, and 0.4-ml fractions were collected. Aliquots were trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Gel Filtration of Whole-Cell Extracts

Yeast cultures were grown to the exponential phase at 24°C, after which 400 OD600 units of cells were collected and converted to spheroplasts by treatment with lyticase. Because the sec38::kanMX4+_SLY1-20_strain grows very slowly, it was inoculated into successively larger cultures for almost 2 wk to obtain enough cells for this experiment. Spheroplasts were Dounce homogenized in 1.5 ml of 190 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, and 1 mM DTT; centrifuged briefly to pellet unlysed cells; and centrifuged again for 30 min at 100,000 × _g_in a TLS55 rotor (Beckman Coulter). Supernatant from this sample was passed through a 0.45-μm syringe filter. Then, 500 μl of the filtrate was applied to a Superose 6 gel filtration column (HR10/30; Pharmacia) that was preequilibrated with 190 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, and 1 mM DTT. The column was run at 0.4 ml/min, and 0.8-ml fractions were collected. Aliquots were TCA precipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Protein levels were quantitated using Kodak ImageStation software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Large-Scale Sec35p-myc Coimmunoprecipitations and Mass Spectrometry

Yeast cultures were grown at 24°C to an OD600 of 3–4. Then, 12,000 OD600 units of cells were collected by centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in 100 ml of buffer D and lysed in a bead beater (Biospec Products). Lysed sample was pelleted for 20 min at 20,000 × g in a SS34 rotor (Beckman Coulter), and the supernatant was transferred to a SW28 rotor (Beckman Coulter), where it was centrifuged for 2 h at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm syringe filter. Filtrate (30 ml) was incubated for 3–4 h with 3 mg of purified c-_myc_antibody (9E10) conjugated to Sepharose beads (Covance) that had been washed in 100 mM glycine pH 2.5, washed in buffer E, and equilibrated in buffer D. Samples were then transferred to a disposable glass column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), where they were washed with 30 ml of buffer D, and 30 ml of buffer E. Bound material was eluted with 100 mM glycine pH 2.5, and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing Sec36p, as determined by immunoblotting, were TCA precipitated and pooled in sample buffer. The cell lysate was reimmunoprecipitated with the same batch of antibody-conjugated Sepharose beads and both sets of elution pools were combined and loaded into a single gel lane. After SDS-PAGE, gels were stained with Coommassie blue, and gel fragments were excised. Samples were subjected to in-gel trypsin digests and the resulting peptides were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometery at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Biopolymers Laboratory. Peptide masses were examined using the MS-FIT algorithm of the Protein Prospector program (Clauser et al., 1999). One missed cleavage was allowed, and significant matches required more than two matching peptides and MOWSE scores >104.

RESULTS

sec36-1 Mutation Blocks Transport of Several Proteins through the Secretory Pathway

In a genetic screen for mutants defective in ribosome synthesis, temperature-sensitive strains were isolated that seemed to be primarily impaired in transport of secretory proteins (Mizuta and Warner, 1994;Li and Warner, 1996). One of these mutants, 271ts, showed accumulation of the secreted protein CPY in its ER-modified p1 form at 37°C, indicating a defect in transport between the ER and medial Golgi compartment (Li and Warner, 1996). When strain 271ts was backcrossed four times to the S288C strain background, temperature sensitivity and the CPY transport defect cosegregated as a single nuclear gene mutation (our unpublished data). We have designated the affected gene_SEC36_, and the altered allele found in strain 271ts_sec36-1_.

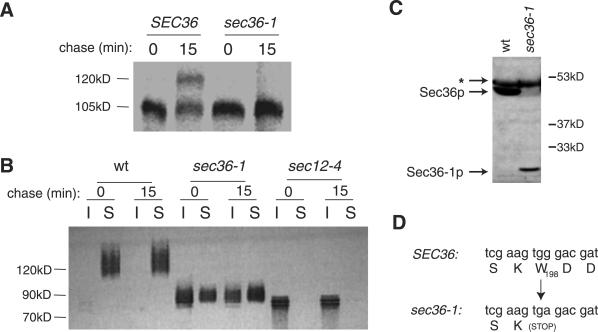

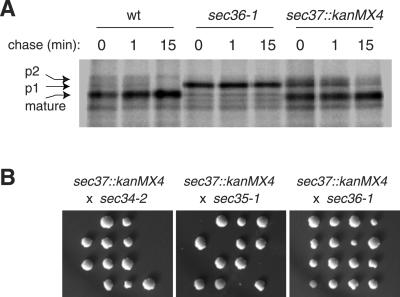

To test whether sec36-1 caused a general transport defect, we evaluated the transport of two other secretory proteins: Gas1p and invertase. Gas1p, a glycophosphatidylinositol-modified plasma membrane protein, acquires polysaccharide modifications in the Golgi, where it matures from a 105-kDa protein to a 125-kDa species. At the cell surface, Gas1p can be degraded by extracellular proteases (Sütterlin et al., 1997), so we studied strains that contain the sec6-4 mutation, which prevents transport of proteins from the Golgi to the plasma membrane (Potenza et al., 1992), to monitor Gas1p maturation without the complication of cell surface proteolysis. In pulse-chase experiments, the_sec6-4_ mutant exhibited significant processing of Gas1p to the 125-kDa species after 15 min at 38°C (Figure1A). In contrast, the sec6-4 s36-1 double mutant strain exhibited no maturation of Gas1p in 15 min at 38°C (Figure 1A), indicating that sec36-1 blocks Gas1p maturation.

Figure 1.

sec36-1 impairs the transport of Gas1p and invertase through the secretory pathway, and causes truncation of Sec36p. (A) sec6-4 (CKY151) and_sec6-4 s36-1_ (CKY728) cells were pulse labeled for 10 min with [35S]methionine and chased for 15 min at 38°C. Radiolabeled Gas1p was detected by immunoprecipitation with Gas1p antibody, followed by SDS-PAGE and PhosphorImager analysis. (B) Wild-type (CKY10), sec36-1 (CKY726), and_sec12-4_ (CKY39) cells were transformed with pNV31, which encodes invertase expressed from the constitutive _TPI1_promoter. Transformants were pulse labeled for 10 min with [35S]methionine and chased for 15 min at 37°C before they were converted into spheroplasts. After centrifugation at 500 × g, pools of intracellular (I) and secreted (S) invertase were detected from pellet and supernatant fractions, respectively, by immunoprecipitation with invertase antibody. (C) Protein extracts from wild-type (CKY10) and sec36-1(CKY726) cells were immunoblotted with affinity-purified Sec36p antibody. To detect the Sec36-1p protein, the blot was overexposed, revealing an immunoreactive band unrelated to Sec36p, indicated by an asterisk (∗). (D) The sec36-1 mutation converts codon 198 to a stop codon.

The secretory protein invertase becomes hyperglycosylated during transport through the Golgi (Novick and Schekman, 1983). In wild-type yeast, invertase matures to a heterogeneous array of 100–150-kDa bands. In a sec36-1 mutant, invertase migrated as a species smaller than 100 kDa, suggesting that it received less outer chain glycosylation that normal (Figure 1B). Furthermore, a significant portion of invertase was blocked in its secretion to the periplasm and accumulated intracellularly (Figure 1B). Collectively, these results indicate that the sec36-1 mutation causes a general block in secretory protein traffic at the restrictive temperature. However, invertase received more outer chain glycosylation in the_sec36-1_ mutant than in the ER-to-Golgi transport mutant_sec12-4_ (Figure 1B), suggesting that the block in transport occurred after invertase had passed through early Golgi compartments.

SEC36 Is in a Previously Uncharacterized ORF

To isolate the SEC36 gene, the pCT3 and YCp50 centromere-based yeast genomic DNA libraries (Rose et al., 1987; Thompson et al., 1993) were screened for clones that complement the inviability of the sec36-1 strain at 38°C. Five plasmids were identified that complemented both the CPY transport defects and temperature-sensitive growth defects. Each contained a 5-kb segment from the left arm of chromosome VII. Removal of a 700-bp_Afl_II fragment internal to the YGL223c ORF on these library plasmids abolished their ability to complement the growth defects of a_sec36-1_ mutant (our unpublished data). Conversely, a plasmid containing only the YGL223c coding region expressed from the p_GAL1_ promoter (pRR35) restored growth to a_sec36-1_ strain at restrictive temperatures (our unpublished data).

To verify that YGL223c is at the sec36-1 locus, we integrated the URA3 marker by homologous recombination into chromosome VII, immediately adjacent to YGL223c. When this integrant was crossed to a sec36-1 mutant strain, the URA3_marker segregated with Ts+ in all 14 tetrads analyzed, showing that this region is tightly linked to the_SEC36 locus.

SEC36 Encodes a Novel Protein That Is Truncated in sec36-1 Mutants

SEC36 encodes an acidic 417 amino acid protein that is ∼48 kDa. This was predicted by sequence analysis and confirmed by the demonstration that affinity-purified Sec36p antibody recognized a 50-kDa protein species in yeast lysates (Figure 1C). A nucleotide sequence was identified by the Génolevures project (http://cbi.labri.u-bordeaux.fr/Genolevures/Genolevures.php3) that may code for a Sec36p homolog in the budding yeast species_Saccharomyces exiguus_. Using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLASTX algorithm, the translation product of this DNA fragment was shown to have 29% identity over a 231-amino acid region of Sec36p. No other sequences with significant similarities to the Sec36p amino acid sequence were found.

To define the mutation responsible for the defects in_sec36-1_, we used the gap repair method (Orr-Weaver et al., 1983), by which a segment of the SEC36 locus on a centromeric plasmid was excised, transformed into a _sec36-1_mutant, and repaired by homologous recombination. The base sequence of the gap-repaired plasmids revealed a point mutation at position 594 (G to A), which converts the codon for Trp198 to a stop codon (Figure 1D). This mutation created a truncated gene product of about half the size of wild-type Sec36p that could be detected by immunoblots of lysates from sec36-1 mutant cells (Figure 1C).

Disruption of SEC36 Leads to a Severe Growth Defect

A disruption of the SEC36 locus was constructed by replacement of the YGL223c ORF in a wild-type diploid strain with_kanMX6_. Tetrads formed after sporulation of this diploid were dissected and grown at temperatures ranging from 18 to 37°C. The spore clones that carried that_sec36_::kanMX6 disruption formed only microcolonies at each temperature (our unpublished data). Identical results were obtained when a 700-base pair region after the first 11% of the YGL223c ORF was replaced by the TRP1 gene (our unpublished data). Viable spores containing sec36_disruptions could be recovered when wild-type SEC36 on a_URA3_-CEN plasmid is also present (our unpublished data). Unlike sister spores lacking the disruption, these cells were inviable on plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid, showing their dependence on_SEC36 for vigorous growth (our unpublished data). The observation that the C-terminal truncations caused by the_sec36-1_ mutation produced a much less severe growth defect than a complete gene deletion suggests that the N terminus of Sec36p is sufficient for its activity in the cell at most physiological temperatures.

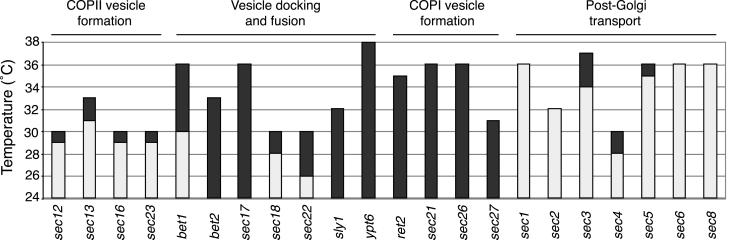

Synthetic Lethality between sec36-1 and Mutations in COPI Coat Subunits and in Vesicle-docking and Fusion Proteins

To identify the stage of vesicle transport that is affected by_sec36-1_, we crossed cells containing the sec36-1_mutation to strains with previously characterized secretory pathway blocks, and examined the meiotic progeny that resulted from sporulation of these diploids. It has been observed that mutations that impair the same stage of vesicle transport often display synthetic lethality, where the combinations of mutations are far more detrimental than the effect of each mutation on its own (Kaiser and Schekman, 1990). As shown in Figure 2, the sec36-1_allele displayed only weak synthetic interactions with COPII vesicle formation mutations and Golgi-to-plasma membrane transport mutations. In contrast, it displayed severe synthetic growth defects with several vesicle docking and fusion mutations such as sec17-1 and_sly1-ts, as well as with all four of the COPI coat protein mutations tested. These data suggest that the function of_SEC36 may be closely tied to both vesicle docking and fusion as well as COPI function.

Figure 2.

sec36-1 is synthetically lethal with mutations that affect vesicle docking and fusion and COPI vesicle transport. A_sec36-1_ mutant (CKY726) was crossed to a set of mutants defining different steps in vesicle trafficking (Table 1). Tetrads were incubated for several days on rich medium at a range of temperatures (24–38°C). The height of each bar indicates the restrictive temperature for the mutation. The shaded region indicates restrictive temperatures for the corresponding double mutant with_sec36-1_. All double mutants with restrictive temperatures of 24°C formed microcolonies on the tetrad dissection plates.

Sec36p Is in a Large Cytosolic Complex

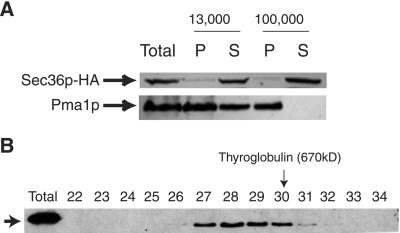

To localize Sec36p, we used yeast cells containing Sec36p tagged at the C terminus with three HA epitopes as the only source of Sec36 protein. Spheroplasts from this strain were fractionated by differential centrifugation, and probed with monoclonal antibody to the HA epitope (12CA5). As shown in Figure3A, Sec36p-HA was predominantly cytosolic. Similar results were obtained with wild-type extracts probed with Sec36p antibody (our unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Sec36p-HA is in a large cytosolic complex. (A) Lysed spheroplasts derived from strain CKY729, expressing HA epitope-tagged Sec36p from a plasmid, were centrifuged at 13,000 and 100,000 × g. Pellet (P) and supernatant (S) samples for each fractionation step were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with either HA antibody (12CA5) to detect Sec36p-HA or antibody to the membrane marker protein Pma1p. (B) CKY729 cells were lysed with glass beads and centrifuged at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was precipitated with 40% ammonium sulfate, fractionated on a DEAE-Sepharose anion exchange column, and then applied to a Superose 6 gel filtration column. The Superose 6 column fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with HA antibody (12CA5) and the fractions that contain all detectable Sec36p-HA are shown. Fraction numbers and the migration of the thyroglobulin size standard (670 kDa) are indicated.

To determine the size of native Sec36p, cytosolic samples from the strain containing Sec36p-HA were first precipitated with 40% ammonium sulfate and further purified over a DEAE-Sepharose anion exchange column. The pooled fractions containing Sec36p-HA were applied to a Superose 6 gel filtration column. Fractions from the Superose 6 column were analyzed by immunoblotting with HA antibody (12CA5). Fractions containing Sec36p-HA eluted from the Superose 6 column before the 670-kDa thyroglobulin marker (Figure 3B), placing Sec36p in a cytosolic complex with an estimated molecular mass of ∼800 kDa. The same gel filtration profile was observed when samples from wild-type cells were analyzed with Sec36p antibody (our unpublished data).

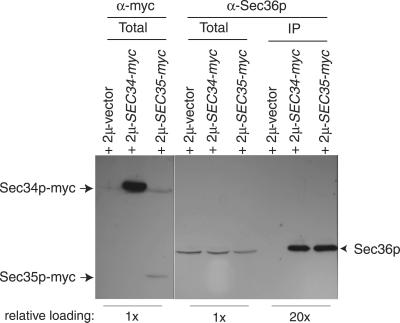

Sec36p Coimmunoprecipitates with Sec34p-myc and Sec35p-myc

The yeast proteins Sec34p and Sec35p were recently found to reside in a large cytosolic complex involved in tethering ER-derived vesicles to the _cis_-Golgi (Kim et al., 1999; VanRheenen_et al._, 1999). Because the sec36-1 mutant displayed characteristics of a vesicle-docking or fusion defect, we surmised that Sec36p might be in the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that endogenous Sec36p efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with both Sec34p-myc and Sec35p-myc (Figure 4). In the absence of tagged versions of either Sec34p or Sec35p, Sec36p was not immunoprecipitated, indicating that Sec36p formed a specific, direct or indirect, association with these proteins. The Sec36-1p protein, produced by a strain containing the sec36-1 mutation, did not efficiently interact with either Sec34p-myc or Sec35p-myc under these conditions (our unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Sec36p coimmunoprecipitates with Sec34p-myc and Sec35p-myc. Wild-type cells (CKY10) were transformed with an empty vector (pRS305-2 μ), or with plasmids encoding Sec34p or Sec35p tagged at their C termini with c-myc epitopes (pRR65 and pRR66, respectively). Extracts from these transformants were subjected to c-_myc_antibody (9E10) immunoprecipitations. The presence of Sec36p in total cell extracts and in immunoprecipitates was monitored by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with affinity-purified Sec36p antibody (right). The presence of tagged Sec34p or Sec35p in total cell extracts was monitored by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with c-myc antibody (9E10; left). Relative amounts of material loaded per lane are noted below the images.

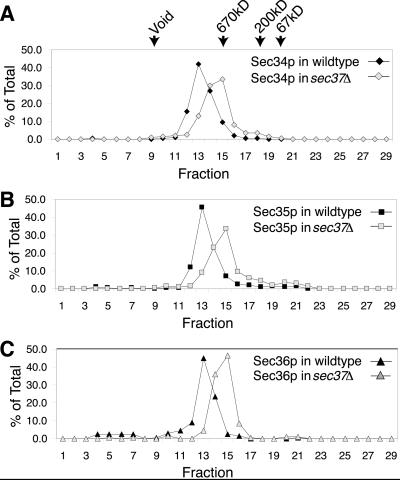

Effects of sec36-1 and sec35-1 on Size of Complex Containing Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p

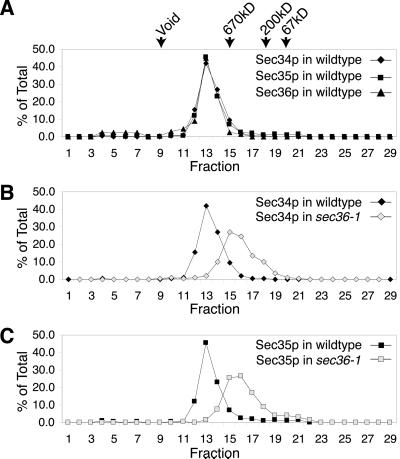

As shown in Figure 5A, when yeast cell lysates were fractionated on a Superose 6 gel filtration column, Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p exactly coeluted, consistent with all three proteins residing in the same complex. Based on these experiments, the apparent size of this complex is >800 kDa, which is larger than the size estimated from gel filtration analysis of lysates that were first precipitated with ammonium sulfate and fractionated by anion exchange chromatography (VanRheenen et al., 1999; Figure 3B).

Figure 5.

sec36-1 affects the mobility of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. (A) Profiles of Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p from wild-type (CKY10) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 gel filtration column. Protein levels are expressed as a percentage of total protein eluted from the column, as detected by immunoblotting. The elutions of the 670-kDa thyroglobulin, 200-kDa β-amylase, and 67-kDa bovine serum albumin size standards from the Superose 6 column, and the void volume, are indicated. (B) Profiles of Sec34p from wild-type (CKY10) and sec36-1 (CKY726) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 column. (C) Profiles of Sec35p from wild-type (CKY10) and sec36-1 (CKY726) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 column.

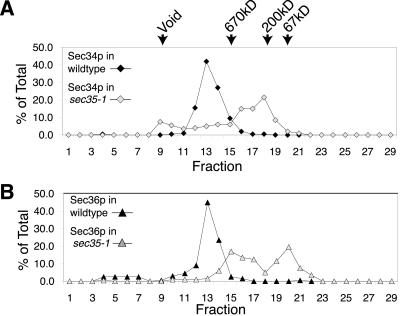

To explore the relationship among Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p further, we monitored the migration of these proteins through a Superose 6 gel filtration column during fractionation of extracts from cells containing either a sec36-1 or sec35-1 mutation. We found that when cytosol from a sec36-1 mutant was fractionated on the Superose 6 column, Sec34p and Sec35p still comigrated, but eluted later than from wild-type extracts, indicating that the size of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex had been altered by_sec36-1_ (Figure 5, B and C). Likewise, when whole-cell cytosol from a sec35-1 mutant was fractionated by Superose 6 chromatography, Sec36p eluted much later than from wild-type extracts (Figure 6), suggesting that the complex in which Sec36p normally resides had been drastically altered by_sec35-1_. These results strongly suggest that Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p are components of the same cytosolic complex. Moreover, they imply that disruption of this complex is the likely cause for the in vivo growth defects observed in strains containing either the_sec35-1_ or the sec36-1 mutation.

Figure 6.

sec35-1 disrupts the Sec36p complex. (A) Profiles of Sec34p from wild-type (CKY10) and sec35-1 (GWY93) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 gel filtration column. Protein levels are expressed as a percentage of total protein eluted from the column, as detected by immunoblotting. (B) Profiles of Sec36p from wild-type (CKY10) and sec35-1(GWY93) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 column.

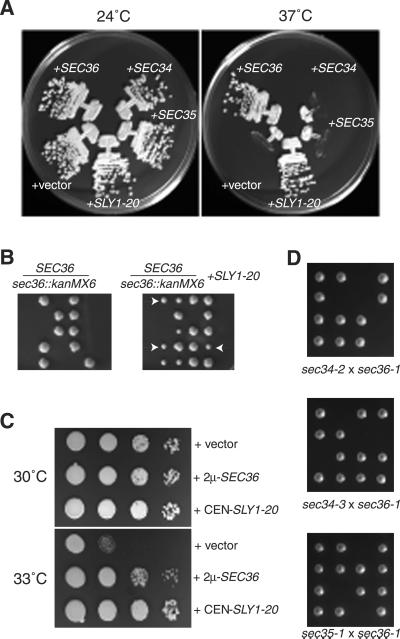

Genetic Evidence for a Functional Link between Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p

To evaluate whether Sec36p functions with Sec34p and Sec35p in cells, we analyzed the genetic relationships between SEC34,SEC35, and SEC36. VanRheenen et al.(1999) reported that the growth defects of strains containing_sec34-1_ and sec35-1 mutations were suppressed by the SLY1-20 dominant allele on a low copy number plasmid. We found that this plasmid efficiently suppressed the growth defect of a_sec36-1_ mutant as well (Figure7A), and partially suppressed the inviability of sec36::kanMX6 cells to the same extent that it partially suppressed the inviability of sec34_and sec35 null cells (Figure 7B; VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999). Furthermore, as reported for overexpression of Sec34p, overexpression of Sec36p was found to partially suppress the_sec35-1 mutation (Figure 7C; Kim et al., 1999). However, overexpression of Sec34p or Sec35p did not affect the growth of sec36-1 strains (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Genetic interactions between SEC36_and SLY1-20, SEC34, and_SEC35. (A) A sec36-1 strain (CKY726) was transformed with low-copy plasmids containing SEC36 or_SLY1-20_ (pRR14 and pSV11, respectively), high-copy plasmids containing SEC34 or SEC35 (pSV25 and pSV17, respectively), or vector alone (pRS306-2 μ), and grown on rich medium at 24 or 37°C. (B) Diploids in which one copy of_SEC36_ was disrupted by kanMX6 (CKY730) were transformed with a plasmid containing SLY1-20(pSV11) and sporulated. Tetrads from untransformed (left) and transformed (right) cells were dissected and incubated on rich medium at 24°C. Arrows indicate examples of colonies of_sec36::kanMX6_ cells containing_SLY1-20_. (C) A sec35-1 mutant (GWY93) was transformed with a plasmid containing SLY1-20 (pSV11), a plasmid that overexpresses Sec36p (pRR31), or vector alone (pRS306-2 μ). Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto rich medium and incubated at 30 or 33°C. (D) A sec36-1 mutant (CKY726 or CKY727) was crossed to a sec34-2 mutant (GWY95),sec34-3 mutant (CKY731), and a _sec35-1_mutant (GWY93). Tetrads from the resulting diploids were incubated for several days at 24°C on rich medium.

Loss of function alleles of SEC34 and SEC35 are each temperature sensitive for growth at 37°C, but sec34 s35 double mutants are inviable at 24°C (VanRheenen et al., 1999). We found that sec36-1 was also synthetically lethal at 24°C with both the sec34-2 and_sec35-1_ mutations (Figure 7D). A new allele of_SEC34_, sec34-3, was obtained from another mutant recovered through the ribosome synthesis screen (strain 394ts; see MATERIALS AND METHODS). We found that sec36-1 was synthetically lethal with this novel allele as well (Figure 7D). Together, these data demonstrate that a close physical and functional relationship exists between Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p.

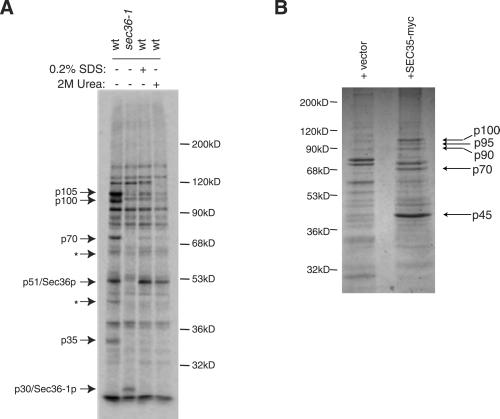

Proteins Likely to be Components of Sec34p/Sec35p Complex Coimmunoprecipitate with Sec36p Antibody

Knowing that Sec36p is in the complex that contains Sec34p and Sec35p, we evaluated whether other components of this complex may associate with Sec36p as well. Accordingly, we found that affinity-purified Sec36p antibody immunoprecipitated a series of protein bands with apparent molecular masses of 35 kDa (p35), 51 kDa (p51), 70 kDa (p70), 100 kDa (p100), and 105 kDa (p105) (Figure8A). These bands were not present in control immunoprecipitates with sec36-1 mutant extracts (Figure 8A), or immunoprecipitations with extracts from_sec36::kanMX6_ strains containing_SLY1-20_ (our unpublished data). Therefore, they likely represented Sec36p and proteins that specifically interact with full-length Sec36p.

Figure 8.

Sec36p and Sec35p-_myc_coimmunoprecipitations. (A) Proteins that immunoprecipitate with Sec36p. Wild-type (CKY10) and sec36-1 mutant (CKY726) cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 3 h before lysis and immunoprecipitation with affinity-purified Sec36p antibody. Two of the samples from wild-type cells were washed with buffer containing either 0.2% SDS or 2 M urea before SDS-PAGE, as indicated. Arrows indicate Sec36p, Sec36–1p, and other proteins that specifically coprecipitated with Sec36p. Asterisks (∗) mark two bands that seem to be specific to the Sec36p immunoprecipitation in this experiment, but varied in intensity between experiments. The migration of molecular weight markers is indicated on the right. (B) Proteins that immunoprecipitate with Sec35p-myc. Lysates from wild-type (CKY10) cells transformed with a plasmid expressing Sec35p-myc (pRR66) or a vector control (pRS305–2 μ) were centrifuged at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was incubated with c-myc antibody (9E10) conjugated to Sepharose beads. Samples were washed extensively and eluted with 100 mM glycine, pH 2.5. Eluted material was TCA precipitated and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Coommassie-stained bands that were specifically immunoprecipitated when Sec35p-myc was present are indicated with arrows. The migration of molecular weight markers is noted on the left.

After Sec36p antibody immunoprecipitates from wild-type cells were washed with 0.2% SDS or 2 M urea, only p51 remained tightly associated with the antibody (Figure 8A), indicating that this species was Sec36p itself, consistent with the predicted size for Sec36p of 48 kDa. A 30-kDa band (p30) was observed in immunoprecipitations from a_sec36-1_ mutant that was not present in immunoprecipitations from wild-type lysates (Figure 8A). This band probably corresponds to the truncated protein produced by the sec36-1 mutation.

The remaining p105, p100, p70, and p35 protein bands were likely to be proteins that associate with Sec36p. Because Sec34p-myc and Sec35p-myc both efficiently immunoprecipitated Sec36p, it was reasonable that Sec36p antibody coimmunoprecipitated Sec34p and Sec35p. Sec34p migrates at 105 kDa by SDS-PAGE (Kim et al., 1999), so it was likely that the p105 band was Sec34p. The predicted molecular mass of Sec35p is ∼32 kDa, so the p35 band was likely to be Sec35p. It was unlikely that the p70 and p100 bands were fragments of Sec34p because significant degradation of endogenous Sec34p had not been observed by immunoblotting with Sec34p polyclonal antibody (our unpublished data). Therefore, these species probably represented previously uncharacterized components of the Sec34p/Sec35p/s36p complex. Initial efforts to obtain enough material to identify these additional proteins by mass spectrometry from complexes isolated by affinity chromatography on a Sec36p antibody column, or using Sec36p tagged with glutathione_S_-transferase, were unsuccessful (our unpublished data).

Proteins Encoded by ORFs YNL041c and YPR105c Coimmunoprecipitate with Sec35p-myc

To identify additional components of the Sec34p/Sec35p/s36p complex, we next performed large-scale c-myc antibody (9E10) immunoprecipitations with extracts from cells overexpressing Sec35p-myc. In these experiments, several protein bands (p70, p90, p95, and p100) seemed to specifically coimmunoprecipitate with Sec35p-myc, indicated as p45 (Figure 8B). Other Sec35p-_myc_–interacting proteins may have been missed in our analysis because we used strains expressing abnormally high levels of Sec35p-myc. For example, endogenous Sec36p was also coimmunoprecipitated with Sec35p-myc in these experiments, as detected by immunoblotting with Sec36p antibody (our unpublished data), but a significant Coomassie-stained protein band around the size of endogenous Sec36p was not observed in elution fractions (Figure 8B).

All four of the protein bands that specifically coimmunoprecipitated in our experiments were digested with trypsin, and analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. The set of peptides in which mass-to-charge (m/z) values were >1000 were used to identify the proteins contained in these samples (Table3). At a mass tolerance of ±25 parts per million (ppm), 10/35 peptides from the p100 band matched the YPR105c-encoded protein, and a nonoverlapping set of 15/35 peptides from the p100 band matched the YNL041c-encoded protein. No matches were found for the p90 and p95 fragments even when the mass tolerance was increased to ±50 ppm, so the proteins contained in these two band remain unidentified. At a mass tolerance of ±50 ppm, 11/20 peptides from the p70 band matched the YPR105c-encoded protein. To demonstrate the significance of this result, the region corresponding to the p70 fragment from the immunoprecipitation lacking Sec35p-myc was also analyzed by mass spectrometry. It yielded no matches, even with a higher mass tolerance window.

Table 3.

Mass spectrometry analysis of proteins that coimmunoprecipitate with Sec35p-myc

| Gel fragment | Mass tolerance (ppm) | ORF of match | Size of protein | MOWSE score | Peptides matched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p100 | ±25 | YPR105c | 99kD | 2.7 × 106 | 10 /35 |

| ±25 | YNL041c | 97kD | 1.7 × 106 | 15 /35 | |

| p95 | ±50 | <2 /39 | |||

| p90 | ±50 | <2 /51 | |||

| p70 | ±20 | YPR105c | 99kD | 1.2 × 104 | 8 /24 |

| ±50 | YPR105c | 99kD | 1.7 × 106 | 11 /20 | |

| p70 control | ±50 | <2 /15 |

Based on their predicted amino acid sequences, the YNL041c- and YPR105c-encoded proteins are estimated to be 97 and 99 kDa, respectively (Saccharomyces Genome Database, Stanford University, Stanford, CA). It was, therefore, likely that the 100-kDa band contained a mixture of these proteins, and that the 70-kDa band was a degradation product of the YPR105c-encoded protein.

Importantly, results from recent large-scale yeast two-hybrid screens show that the YNL041c-encoded protein interacts with both Sec35p and Sec36p, and that the YPR105c-encoded protein interacts with Sec35p (Uetz et al., 2000; Ito et al., 2001). These interactions strongly suggest that both YNL041c and YPR105c encode proteins that physically associate with Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p. Consequently, we have designated YNL041c and YPR105c as_SEC37_ and SEC38, respectively.

SEC37 and SEC38 Encode Conserved Proteins

Both SEC37 and SEC38 encode proteins that are probably cytosolic or peripherally associated with membranes, because their predicted sequences lacked obvious transmembrane domains. Sec37p and Sec38p share significant amino acid sequence similarity along their lengths with predicted proteins from other budding yeast species (http://cbi.labri.u-bordeaux.fr/Genolevures/Genolevures.php3) as well as from other eukaryotes (Table4). Therefore, Sec37p and Sec38p seem to be highly conserved eukaryotic proteins. For Sec38p, the_Arabidopsis thaliana_ homolog is distinguished from the others by the presence of an N-terminal extension (Table 4). For Sec37p, the S. cerevisiae protein is longer than related proteins from other species, primarily due to a 100–200-amino acid extension at the N terminus (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sec37p and Sec38p homologs

Disruption of SEC37 Produces Defects Similar to Those Caused by Mutations in SEC34 and SEC35

We found that haploid cells in which the SEC37 was replaced with kanMX4 grew on complete medium at temperatures ranging from 24 to 37°C (our unpublished data). Therefore,SEC37 was apparently dispensable for robust growth at physiological temperatures.

To test whether sec37::kanMX4 cells have any defect in vesicle-mediated transport, we monitored the transport of CPY through the secretory pathway by pulse-labeling and immunoprecipitation. In wild-type cells, CPY was efficiently processed to its mature form after 1 min, whereas in the_sec37::kanMX4_ strain, CPY was delayed in its conversion from the ER-modified p1 form to the Golgi-modified p2 form (Figure 9A). The p1 form of CPY was previously shown to accumulate in ER-to-Golgi secretory pathway mutants, including strains containing mutations in SEC34 or_SEC35_ (Li and Warner, 1996; Wuestehube et al., 1996).

Figure 9.

Disruption of SEC37 slows the rate of ER-to-Golgi transport and is synthetically lethal with_sec34-2_ and sec35-1 at 24°C. (A) Wild-type (CKY10) cells, sec36-1 (CKY726) cells, and_sec37::kanMX4_ (CKY733) cells were pulse labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min at 37°C, followed by a chase for the indicated times, and immunoprecipitation with CPY antibody to monitor the conversion of CPY from the p1 (ER-modified) form, to the p2 (Golgi-modified) and mature (vacuole processed) forms. (B) sec37::kanMX4 (CKY733 or CKY734) cells were crossed to sec34-2 (GWY95),sec35-1 (GWY93), and sec36-1 (CKY726) cells. After sporulation, tetrads were dissected and incubated at 24°C on rich medium. Spores that seemed inviable actually formed microcolonies that were inferred to be double mutants by tetrad analysis.

For evidence that disruption of SEC37 specifically affected the complex that contains Sec34p and Sec35p, a_sec37::kanMX4_ halpoid strain was crossed to strains containing sec34-2, sec35-1, and_sec36-1_ alleles. As shown in Figure 9B, deletion of_SEC37_ was synthetically lethal at 24°C with_sec34-2_ and sec35-1, but not with_sec36-1_.

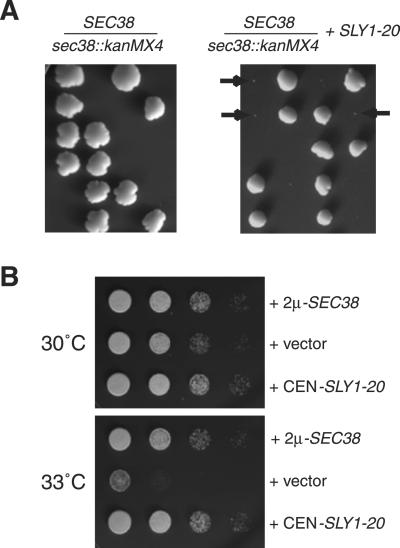

SEC38 Is Essential and Displays Genetic Interactions Consistent with a Functional Link to SEC34 and SEC35

Haploid cells in which SEC38 was replaced by_kanMX4_ were inviable at 24°C, and could not form visible microcolonies (Figure 10A). However, in the presence of the SLY1-20 plasmid, these_sec38::kanMX4_ cells formed visible microcolonies (Figure 10A). Previous results have implied that the ability to be suppressed by SLY1-20 is a hallmark of mutations in genes that encode proteins with functions related to Sec34p and Sec35p function (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999; Figure 7). Therefore, this result suggests that the function of Sec38p is related to that of Sec34p and Sec35p. Likewise, it was observed previously that overexpression of Sec34p, Sec35p, or Sec36p, suppressed the temperature-dependent growth defects of a sec35-1 mutant strain at 33°C, and we found that overexpression of Sec38p has a similar effect (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999; Figures 7C and 10B). Collectively, these results support a functional as well as physical connection between Sec38p and Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p. Our results are consistent with those published elsewhere during submission of this article, in which Sec38p/Sgf1p was isolated as a high-copy suppressor of the temperature sensitivity of sec35-1 that interacts with Sec35p and cofractionates with Sec34p and Sec35p (Kim_et al._, 2001).

Figure 10.

Genetic interactions between the essential_SEC38_ gene and both SLY1-20 and_SEC35_. (A) Diploid strain in which one copy of the_SEC38_ locus was disrupted with kanMX4(CKY736) was transformed with a URA3_-marked plasmid containing SLY1-20 (pSV11). The untransformed (left) and transformed (right) diploids were sporulated at 24°C on rich medium. Some of the microcolonies that arose are marked by arrows. Tetrad analysis revealed that all inviable spores and microcolonies contained_sec38::kanMX4. (B) _sec35-1_mutant cells (GWY93) were transformed with a low-copy plasmid containing SLY1-20 (pSV11), a high-copy plasmid containing SEC38 (pRR72), or a vector plasmid (pRS426). Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto rich medium at 30 or 33°C and grown for several days.

Disruption of SEC37 or SEC38 Affects Size of Complex Containing Sec34p and Sec35p

To determine how Sec37p and Sec38p might influence the complex that contains Sec34p and Sec35p, extracts from cells containing either_SEC37_ disrupted with kanMX4 or _SEC38_disrupted with kanMX4 were fractionated on a Superose 6 gel filtration column. When sec37::kanMX4 cell extracts were fractionated this way, Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p still comigrated through the column, but were slightly delayed relative to their migration during fractionation of wild-type extracts (Figure11), implying that deletion of Sec37p results in a partial disruption of the complex (Table5).

Figure 11.

Deletion of SEC37 affects the mobility of the Sec34p/s35p complex. (A) Profiles of Sec34p from wild-type (CKY10) and sec37::kanMX4 (CKY733) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 gel filtration column. Protein levels are expressed as a percentage of total protein eluted from the column, as detected by immunoblotting. (B) Profiles of Sec35p from wild-type (CKY10) and_sec37::kanMX4_ (CKY733) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 column. (C) Profiles of Sec36p from wild-type (CKY10) and sec37::kanMX4 (CKY733) cell extracts fractionated on a Superose 6 column.

Table 5.

Characteristics of components of the yeast Sec34p/Sec35p complex

| Gene | ORF | Size of protein | Organisms with homologsa | Difference in mobility of Sec34p/Sec35p in mutant relative to wild typeb | Null phenotype (24°C) | Two-hybrid interactionsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEC34 | YER157w | 93 kD | H,D,A,S,C,Y | Not determined | Visible microcolonies | Sec34p-Sec35p |

| SEC35 | YGR120c | 32 kD | Y | 3.0, 5.0 (Sec34p) | Visible microcolonies | Sec35p-Sec34p |

| Sec35p-Sec37p | ||||||

| Sec35p-Sec38p | ||||||

| SEC36/COD3 | YGL223c | 48 kD | Y | 2.5 | Visible microcolonies | Sec36p-Sec37p |

| SEC38/SGF1/COD1 | YPR105c | 99 kD | H,D,A,S,C,Y | 4.5 (Sec34p) | No visible growth | Sec38p-Sec35p |

| 6.5 (Sec35p) | ||||||

| SEC37/COD2 | YNL041c | 97 kD | H,D,A,S,C,Y | 1.2 | Wild-type growth | Sec37p-Sec35p |

| Sec37p-Sec36p | ||||||

| COD4 | YNL051w | 46 kD | H,D,A,S,C,Y | 1.3 | Wild-type growth | |

| COD5 | YGL005c | 32 kD | Y | 0.5 | Wild-type growth | |

| DOR1 | YML071c | 70 kD | H,D,A,S,C,Y | 1.4 | Wild-type growth |

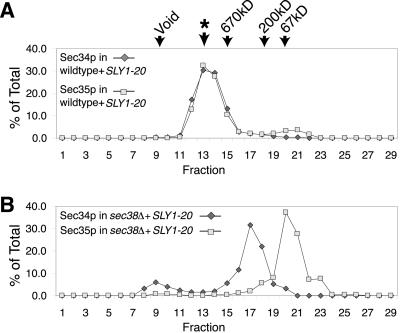

Because SEC38 is essential, to analyze the effects of deleting SEC38, we used a sec38::kanMX4_strain containing the SLY1-20 plasmid. We found that the_SLY1-20 plasmid did not affect the elution of Sec34p or Sec35p from the Superose 6 column (Figure12A). Disruption of SEC38, however, had a dramatic effect on the migration of Sec34p and Sec35p from the column (Figure 12B). These two proteins no longer coeluted and were largely distributed to distinct fractions. This result suggests that Sec38p may be necessary for Sec34p and Sec35p to interact, as well as for the integrity of the complex as a whole. This may be why disruption of SEC38 had such a drastic effect on cell viability. Conversely, the more subtle effects that loss of_SEC37_ has on the complex may explain why disrupting that gene did not cause a significant growth defect.

Figure 12.

Deletion of SEC38 disrupts the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. (A) As a control to show that the presence of_SLY1-20_ does not significantly alter the mobility of the complex, Sec34p and Sec35p were fractionated on a Superose 6 gel filtration column from wild-type (CKY10) cell extracts containing_SLY1-20_ (pSV11). An asterisk (∗) designates the peak of Sec34p and Sec35p elution during fractionation of extracts from wild-type (CKY10) cells lacking SLY1-20. Protein levels are expressed as a percentage of total protein eluted from the column, as detected by immunoblotting. (B) Profiles of Sec34p and Sec35p from extracts of _sec38::kanMX4_cells containing SLY1-20 (CKY735) fractionated on a Superose 6 column.

Evidence That Cod4p, Cod5p, and Dor1p Function in Sec34p/Sec35p Complex In Vivo

While this article was in preparation, Whyte and Munro (2001)reported isolation of a complex containing the proteins Cod4p, Cod5p, and Dor1p in addition to the five subunits of Sec34p/Sec35p complex that we have described herein. We were interested, therefore, to extend our genetic and biochemical analyses to these three additional gene products. We first tested disruption of COD4,COD5, and DOR1 for their effects on cell viability and protein transport. Although strains containing_cod4::kanMX4_, cod5::kanMX4, and dor1::kanMX4 alleles display wild-type growth at a range of temperatures, we found that each of these mutations causes a severe synthetic growth defect in combination with the_sec35-1_ allele at 24°C (Figure13A). A strain carrying_dor1::kanMX4_ displayed the most severe synthetic growth defect, and also displayed a significant delay in the maturation of CPY from p1 (ER form) to p2 (Golgi form) (Figure 13B).

Figure 13.

Tests for the involvement of Cod4p, Cod5p, and Dor1p in the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. (A) A sec35-1 mutant (GWY93) was crossed to cod5::kanMX4 (Y04373),dor1::kanMX4 (Y06484), and_cod4::kanMX4_ (Y07209) strains. Tetrads from the resulting diploids were incubated for several days at 24°C on rich medium. Microcolonies and inviable spores were inferred to be double mutants based on the phenotypes of the remaining spores. (B) Wild-type (CKY10) cells, and cod5::kanMX4(Y04373), dor1::kanMX4 (Y06484), and_cod4::kanMX4_ (Y07209) cells containing a plasmid with the MET15 gene to complement their methionine auxotrophy were pulse labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min at 37°C, followed by a chase for the indicated times. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with CPY antibody to monitor maturation of CPY. (C) Extracts from_cod5::kanMX4_ (Y04373),dor1::kanMX4 (Y06484), or_cod4::kanMX4_ (Y07209) cells were fractionated on a Superose 6 column and probed with Sec34p antibody. Identical profiles were seen when fractions were probed with Sec35p antibody. Protein levels are expressed as a percentage of total protein eluted from the column, as detected by immunoblotting. An asterisk (∗) designates the peak of Sec34p and Sec35p elution during fractionation of extracts from wild-type (CKY10) cells.

To test the effect of these alterations on the complex that contains the majority of Sec34p and Sec35p, we prepared cytosol from each disruption strain and determined the size of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex by gel filtration. All three deletions caused a slight shift in the mobility of Sec34p and Sec35p that was similar to that observed when_SEC37_ was deleted (compare Figure 13C with Figure 11).

DISCUSSION

Identification of Proteins in a Complex with Sec34p and Sec35p

Our investigation began with the identification of_sec36-1_, a conditional mutation in a new secretion gene. Examination of Sec36p revealed that it binds to Sec34p and Sec35p, two genes that have been shown recently to be part of a large complex required for transport of proteins through early steps in the secretory pathway (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999; Kim et al., 1999). A parallel evaluation of mutations in_SEC34_, SEC35, and SEC36 revealed that 1) missense mutations in SEC34, SEC35, and_SEC36_ are synthetically lethal with one another; 2) these missense alleles cause a pleiotropic block in protein trafficking at either the ER or Golgi stage of the secretory pathway; 3) disruption of any one of these genes results in a severe growth defect that can be partially suppressed by the SLY1-20 allele; and 4) overexpression of Sec34p or Sec36p partially suppresses the temperature-dependent growth defects caused by the _sec35-1_mutation. Together, these genetic observations indicate that Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p function together in a common process necessary for protein trafficking in the early part of the secretory pathway.

Affinity isolation of protein complexes containing Sec35p had previously revealed a set of copurifying polypeptides (Kim et al., 1999). We found an overlapping set of protein bands after affinity isolation of Sec36p, reinforcing the idea that the native Sec34p/Sec35p complex contains a number of protein species in addition to Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p. By using mass spectrometry we identified two additional proteins present in affinity-isolated complexes, which we designate Sec37p and Sec38p. Both Sec37p and Sec38p associate with the Sec34p/Sec35p complex as shown by coimmunoprecipitation experiments and yeast two-hybrid interactions. Disruption of SEC38 is lethal, but can be partially suppressed by a SLY1-20_mutation. Moreover, overexpression of SEC38 can suppress growth defects caused by the sec35-1 mutation. Disruption of_SEC37 alone has little effect on cell growth, but a deletion of SEC37 is synthetically lethal with sec34 and_sec35_ missense mutations. These genetic interactions indicate that both SEC37 and SEC38 contribute to the in vivo function of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex.

Proteins That Comprise Core of Sec34p/Sec35p Complex

Most of the Sec34p, Sec35p, and Sec36p proteins are in the cytosolic fraction of yeast cell lysates. Gel filtration of cytosol shows that all three proteins cofractionate as a large complex with an estimated mass of >800 kDa. Because gel filtration seemed to be a more gentle fractionation procedure than affinity isolation, which includes potentially disruptive washing steps, we have used gel filtration of crude cytosolic extracts as a way to compare the structure of the Sec34p/s35p complex in different mutants. By this assay, mutations in_SEC35_, SEC36, and SEC38 cause a dramatic effect on the size of native complex as shown by the redistribution of other proteins in the complex to low molecular weight fractions.

Thus, mutations in SEC34, SEC35,SEC36, and SEC38 are similar in that they are either lethal or greatly compromise cell growth, they result in a pronounced defect in transport of CPY through the early stages of the secretory pathway, and they disrupt the integrity of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. We therefore propose that these four proteins comprise a functional core of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex.

Multiple components of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex seem to be conserved among eukaryotic species, indicating that a homolog of the complex exists in metazoans as well as in yeast (Suvorova et al., 2001; Whyte and Munro, 2001). It is therefore surprising that among the four genes that we have found to be the most important for the function and integrity of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex, Sec35p and Sec36p seem to be present only in yeast species. It seems possible that the counterparts of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex in metazoans contain proteins that perform the same function as Sec35p and Sec36p without sharing obvious sequence similarity.

Peripheral Components of Sec34p/Sec35p Complex

Deletion of SEC37 does not interfere with cell growth and only causes a small delay in the processing of CPY. Consistent with the relatively minor phenotypic effects of a _sec37Δ_mutation, extracts prepared from this deletion strain revealed a relatively small alteration in the mobility of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. Although changes in mass of a large protein complex can only crudely be approximated by gel filtration, the change in mobility caused by sec37Δ is consistent with the absence of only the ∼100-kDa Sec37p protein itself and does not give any indication that association of the core proteins has been affected. Thus, Sec37p seems to be peripherally associated with the complex and to not be required for its essential cellular function.

Recently, Whyte and Munro (2001) reported the affinity isolation of eight different proteins, including Sec34p and Sec35p, by their association with Dor1p, a protein involved in Golgi function. Three of these proteins, Dor1p, Cod4p, and Cod5p, were not among the components that copurified with Sec35p-myc that we were able to identify by mass spectroscopy. However, two proteins bands that sometimes coimmunoprecipitated with Sec36p in our experiments (Figure 8A, asterisks), migrate at positions consistent with Dor1p (70 kDa, upper asterisk), and Cod4p or Cod5p (46 or 32 kDa, lower asterisk). We are not sure whether we did not identify Dor1p, Cod4p, or Cod5p in our mass spectroscopic analysis because the form of the complex that we isolated using Sec35p-myc has a different subunit composition than the complex isolated by association with Dor1p-protein A, or because some of the polypeptides in the complex had dissociated or were degraded during the affinity isolation. Nevertheless, we were interested in applying our gel filtration assay to mutants in these additional genes to ascertain their effect on the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. Extracts from strains carrying cod4Δ,cod5Δ, or dor1Δ revealed relatively small differences in the elution of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex, similar to those observed for sec37Δ. Phenotypic tests of_cod4Δ, cod5Δ_, and dor1Δ strains revealed no impairment of growth and only very minor defects in CPY maturation. We therefore tentatively conclude that Cod4p, Cod5p, and Dor1p are also peripheral components of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. We were interested to know whether the cytosolic form of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex has a homogenous structure comprised of all eight identified proteins or whether different subcomplexes might exist. Unfortunately, the shift in elution volume caused by deletion of any of the four peripheral components (Sec37p, Cod4p, Cod5p, or Dor1p) is too small relative to the dispersion of the complex during gel filtration to judge whether isoforms of the complex lacking one or more peripheral proteins might exist in a wild-type cytosolic fraction.

Possible Cellular Functions of Sec34p/Sec35p Complex

Two lines of evidence have suggested a role for the Sec34p/s35p complex in transport vesicle tethering with the _cis_-Golgi or some other Golgi compartment. First, in a reconstituted assay for transport between the ER and Golgi, extracts from sec34-2_and sec35-1 mutants displayed defects in the attachment of ER-derived vesicles to Golgi membranes (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999). Second, sequence similarities have been detected between two components of the Sec34p/s35p complex (Dor1p and Sec34p) and components of the exocyst complex (Sec5p and Exo70p), which is required for tethering of post-Golgi secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane (TerBush et al., 1996; Whyte and Munro, 2001). However, we believe that the assignment of a vesicle tethering function to the Sec34p/Sec35p complex remains tenuous for the following reasons. First, the in vitro assays that revealed a tethering defect in_sec34 and sec35 mutants used membrane and cytosolic fractions derived from mutant cells that had been incubated at the restrictive temperature for several hours (VanRheenen et al., 1998, 1999). Thus, it is quite possible that the observed tethering defect could have been a secondary consequence of defective Golgi organization in the cells from which the constituents for the in vitro reaction were derived. Moreover, analysis of _sec36-1_mutants revealed no transport defect for any of the steps in ER-to-Golgi transport, including vesicle tethering, by an assay of the in vitro transport activity of extracts that had been incubated at the restrictive temperature (Barlowe, personal communication). Finally, the observed sequence similarities to tethering complex proteins do not necessarily imply a conserved function. Dor1p does show clear sequence similarity to Sec5p, but the reported similarities between Sec34p and Exo70p are of uncertain functional significance (identification of these alignments requires multiple iterations of PSI-BLAST searches). Therefore, it seems premature to conclude that the Sec34p/Sec35p complex performs the same basic function as the exocyst, given the rather limited extent of sequence alignment between these two very large complexes.

A key limitation in our knowledge of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex that has hindered a more precise definition of its molecular function, is that the steps in the secretory pathway that specifically require the Sec34p/Sec35p complex have not yet been precisely delineated. Sec34p and Sec35p have been implicated both in transport between the ER and Golgi and in transport between the Golgi apparatus and the prevacuole/late endosome (Spelbrink and Nothwehr, 1999; VanRheenen_et al._, 1999). Whyte and Munro (2001) also found that the plasma membrane protein Snc1p-GFP was mislocalized when Sec34p/Sec35p complex components are absent. Although, it is possible that the Sec34p/Sec35p complex is directly involved in multiple intracellular transport steps, it seems that all of the observed secretory pathway defects could most simply be explained as indirect consequences of a transport defect that disrupts the organization of the Golgi compartment. Defects that disrupt sites for delivery of vesicles to the Golgi could lead to defects in transport both from the ER and from the prevacuole/late endosome. Also, the mislocalization of Snc1p-GFP could simply have been the consequence of faulty transport of this protein through late-Golgi compartments.

How might the Sec34p/Sec35p complex influence transport through the Golgi apparatus? A tantalizing clue is the synthetic lethal interactions between sec36-1 and four different COPI mutations. The severity and specificity of these genetic interactions suggest that Sec36p, and by extension the Sec34p/Sec35p complex, might participate directly in the assembly or function of the COPI vesicle coat. Mutations in genes encoding other components of the complex also showed synthetic growth defects with COPI mutants, albeit not always as severe (our unpublished data), and sec36-1 was also synthetically lethal at 24°C with a deletion of ARL1, which encodes an Arf-like protein (Lee et al., 1997; our unpublished data). The best-characterized function of COPI in yeast is the retrieval of selected proteins from the Golgi to ER (Gaynor_et al._, 1994; Schröder et al., 1995; Lewis and Pelham, 1996). However, we found no evidence that_sec36-1_ mutants or _sec37::kanMX4_mutants are defective in the retrieval of the KKXX-tagged proteins Emp47p-myc or invertase-WBPI from the Golgi to the ER (our unpublished data). Although these phenotypic tests argue against a direct role for the Sec34p/Sec35p complex in COPI-mediated retrieval to the ER, it remains possible that the Sec34p/Sec35p complex may have a specific part in COPI-mediated traffic between Golgi subcompartments (Gaynor_et al._, 1998; Lowe and Kreis, 1998). This hypothesis is consistent with the findings that membrane-associated pools of the human homologs of Sec34p, Sec38p/Cod1p, and Dor1p are found throughout the Golgi apparatus (Suvorova et al., 2001; Whyte and Munro, 2001), and that the human homolog of the Cod4p subunit stimulates transport between Golgi subcompartments in vitro (Walter_et al._, 1998). Once more specific assays for inter-Golgi transport become available it may be possible to define more precisely the molecular function of the Sec34p/Sec35p complex. It might also be possible to determine whether the more peripheral subunits are responsible for different transport steps than the subunits that comprise the core of the complex.

Note added in proof. By agreement with several labs working on the Sec34p/Sec35p complex, the complex has been renamed the COG complex (for conserved oligomeric Golgi complex). Accordingly, the ORFs encoding components of the complex have been renamed as follows: YGL223c is COG1, YGR120c is_COG2_, YER157w is COG3, YPR105c is_COG4_, YNL051w is COG5, YNL041c is_COG6_, YGL005c is COG7, and YML071c is_COG8_.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Elizabeth Chitouras for preliminary experiments with some of the mutants, and to George L. Fox for exhaustive help in preparing the manuscript. We thank the following scientists and members of respective laboratories for reagents: Hugh Pelham (pNV31), Hidde Ploegh (CPY antibody), Howard Riezman (Gas1p antibody), and M.G. Waters (Sec34p and Sec35p antibodies, GWY strains, and pSV plasmids). We also acknowledge the following scientists for extensive, open communication about results: M.G. Waters and Elbert Chiang (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ), Susan Ferro-Novick (Yale University, New Haven, CT), and Monty Krieger (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA). This work was funded in part by a National Institutes of Health predoctoral traineeship to R.J.R. B.L. was supported on National Institutes of Health grant GM-25532 awarded to Jonathon R. Warner (Albert Einstein). Both R.J.R. and C.A.K. were supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM-46941 (to C.A.K.).

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe C. COPII: a membrane coat that forms endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00618-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Ballew N, Barlowe C. Initial docking of ER-derived vesicles requires Uso1p and Ypt1p but is independent of SNARE proteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:2156–2165. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauser KR, Baker P, Burlingame AL. Role of accurate mass measurement (+/− 10 ppm) in protein identification strategies employing MS or MS/MS and database searching. Anal Chem. 1999;71:2871–2882. doi: 10.1021/ac9810516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascher C, Ossig R, Gallwitz D, Schmitt HD. Identification and structure of four yeast genes (SLY) that are able to suppress the functional loss of YPT1, a member of the RAS superfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:872–885. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade P, Gimeno RE, Holzmacher E, Teung P, Kaiser CA. Yeast SEC16 gene encodes a multidomain vesicle coat protein that interacts with Sec23p. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:311–324. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor EC, Graham TR, Emr SD. COPI in ER/Golgi and intra-Golgi transport: do yeast COPI mutants point the way? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404:33–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor EC, te Heesen S, Graham TR, Aebi M, Emr SD. Signal-mediated retrieval of a membrane protein from the Golgi to the ER in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:653–665. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno RE, Espenshade P, Kaiser CA. SED4 encodes a yeast endoplasmic reticulum protein that binds Sec16p and participates in vesicle formation. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:325–338. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Sacher M, Barrowman J, Ferro-Novick S, Novick P. Protein complexes in transport vesicle targeting. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Chiba T, Ozawa R, Yoshida M, Hattori M, Sakaki Y. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CA, Gimeno RE, Shaywitz DA. Protein secretion, membrane biogenesis, and endocytosis. In: Jones EW, Pringle JR, Broach JR, editors. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Cell Biology. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1997. pp. 91–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CA, Schekman R. Distinct sets of SEC genes govern transport vesicle formation and fusion early in the secretory pathway. Cell. 1990;61:723–733. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90483-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DW, Massey T, Sacher M, Pypaert M, Ferro-Novick S. Sgf1p, a new component of the sec34p/sec35p complex. Traffic. 2001;2:820–830. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DW, Sacher M, Scarpa A, Quinn AM, Ferro-Novick S. High-copy suppressor analysis reveals a physical interaction between Sec34p and Sec35p, a protein implicated in vesicle docking. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3317–3329. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]