Ascospore Formation in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (original) (raw)

Abstract

Sporulation of the baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a response to nutrient depletion that allows a single diploid cell to give rise to four stress-resistant haploid spores. The formation of these spores requires a coordinated reorganization of cellular architecture. The construction of the spores can be broadly divided into two phases. The first is the generation of new membrane compartments within the cell cytoplasm that ultimately give rise to the spore plasma membranes. Proper assembly and growth of these membranes require modification of aspects of the constitutive secretory pathway and cytoskeleton by sporulation-specific functions. In the second phase, each immature spore becomes surrounded by a multilaminar spore wall that provides resistance to environmental stresses. This review focuses on our current understanding of the cellular rearrangements and the genes required in each of these phases to give rise to a wild-type spore.

INTRODUCTION

The generation of ascospores is a defining feature of the fungal phylum Ascomycota. Ascospores are generally found in clusters of four or eight spores within a single mother cell, the ascus. These spores are formed as a means of packaging postmeiotic nuclei. As such, they represent the “gametic” stage of the life cycle in these fungi. The creation of these specialized cells requires a cell division mechanism distinct from that used during vegetative growth of fungal cells. This review will focus on this process in the best-studied model, the baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

OVERVIEW OF ASCOSPORE FORMATION

An overview of the cytological events of sporulation in S.cerevisiae is shown in Fig. 1. Diploid cells of S. cerevisiae modify their growth in response to nutrient availability. In the presence of nutrients they grow in budding form. The presence of a poor nitrogen source such as proline will trigger the onset of mitotic growth in a pseudohyphal form (46). The complete absence of nitrogen, and the presence of a nonfermentable carbon source such as acetate, causes the cells to exit the mitotic cycle, undergo meiosis, and sporulate (40).

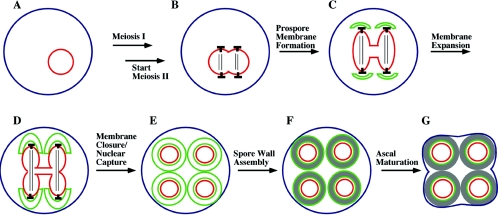

FIG. 1.

(A to G) Overview of the stages of spore and ascus formation. In the presence of a nonfermentable carbon source, diploid cells starved for nitrogen will undergo meiosis. During the second meiotic division, the SPBs (indicated as ⟂︁), which are embedded in the nuclear envelope (shown in red), become sites for formation of prospore membranes (shown in green). As meiosis II proceeds, the prospore membranes expand and engulf the forming haploid nuclei. After nuclear division, each prospore membrane closes on itself to capture a haploid nucleus within two distinct membranes. Spore wall synthesis then begins in the lumen between the two prospore membrane-derived membranes. After spore wall synthesis is complete, the mother cell collapses to form the ascus.

When triggered to enter the sporulation program, cells exit the mitotic cycle from the G1 phase (40, 80). This is followed by premeiotic DNA synthesis and entry into the meiotic divisions. As with mitosis in yeast, meiosis is “closed”; that is, it takes place without breakdown of the nuclear envelope. The spindle microtubules are nucleated from the nuclear face of spindle pole bodies (SPBs) that span the nuclear envelope (21). In G1 cells, there is a single SPB present in the cell. This SPB duplicates prior to meiosis I to generate the two poles of the meiosis I spindle. SPB duplication proceeds by a conservative process in which the daughter SPB is assembled adjacent to the mother and then migrates to the opposite side of the nucleus to form a spindle (2). As the cell exits from meiosis I, the SPBs duplicate again and the two meiosis II spindles are generated (Fig. 1B). Separation of the sister chromatids during anaphase II pulls a haploid set of chromosomes into each of four lobes of the nucleus. These lobes then pinch off at the end of meiosis II to generate four haploid nuclei.

The process of spore formation begins during meiosis II. Vesicles are recruited to the cytoplasmic side of each of the four SPBs, where they coalesce to form flattened double-membrane sheets termed prospore membranes (often referred to as the prospore wall in the older literature). (Fig. 1C) (21, 99). These four prospore membranes expand during the course of meiosis II so that at the time of nuclear division each prospore membrane completely engulfs the nuclear lobe to which it is anchored via the SPB (Fig. 1D). After nuclear division, the open end of each prospore membrane closes off so that each daughter nucleus and its associated cytoplasm is completely encapsulated within a double membrane (Fig. 1E). The closure of the prospore membranes is a cytokinesis event, generating four autonomous prospores. Of the two distinct membranes derived from the prospore membrane, the one closest to the nucleus now serves as the plasma membrane of the prospore.

The prospores mature into spores through the synthesis of a spore wall. Assembly of the spore wall occurs initially in the lumen between the two prospore membrane-derived membranes (Fig. 1F) (91). As described below, the outer of these two membranes breaks down during the process of spore wall formation. Once complete, the spore wall confers on the spore resistance to a variety of environmental stresses (156). After the completion of the spore wall, the now anucleate mother cell, which remains intact throughout sporulation, is remodeled to serve as an ascus that encapsulates the four spores of the tetrad (Fig. 1G). A mutation that delays or blocks the shrinking of the ascus around the spore has been described, suggesting that ascal maturation may be an active process, rather than a simple lysis of the anucleate cell (105). The mechanisms controlling this process remain unknown, although vacuolar proteases have been suggested to play a role in the remodeling (187).

AN UNDERLYING TRANSCRIPTIONAL CASCADE

Starvation and entry into meiosis are prerequisites for spore formation to begin. Both the control of entry into meiosis and the details of meiotic chromosome segregation have been the subject of earlier reviews (57, 86, 98, 138, 160) and will only be touched on here. The coordination of spore formation with these other events is achieved through an underlying transcriptional cascade (175). Studies using Northern analysis identified a number of transcripts whose expression was induced by sporulation conditions (56, 126). Time course studies grouped these transcripts broadly into three categories: early, middle, and late genes. As more genes have been characterized, subcategories such as early-middle and mid-late have been added to the classifications (13, 120).

The use of transcriptional microarrays to examine the pattern of transcription during sporulation has confirmed and expanded on these original studies (25, 130). Several waves of induction are seen. Immediately upon transfer to sporulation medium, many genes involved in metabolic adaptation are induced. Subsequent to that immediate response, a set of transcripts termed the early genes are upregulated. Many of these genes are involved in meiotic chromosome metabolism. After the early genes, a second large set of genes are coordinately induced. These middle genes include those involved in progression through the meiotic divisions, such as genes encoding cyclins and components of the anaphase-promoting complex, as well as many of the genes encoding proteins directly involved in the construction of the spore (described below) (25, 130). The transcription factor NDT80 is required for the induction of these middle genes (26). The common regulation of meiotic functions and spore assembly functions by Ndt80p may help maintain coordination between the two processes.

After the middle genes, at a time roughly correlated with the completion of meiosis II, a smaller set of mid-late genes are induced, and subsequent to that a set of “late” genes are induced. While some of the late genes are required for the assembly of the spore wall, others appear to be more general stress response genes, and still others are haploid-specific genes whose induction may correlate with restoration of the haploid state in the spores (130).

The characterization of sporulation-induced genes has been a fruitful source for study of meiosis- and sporulation-defective mutants. In particular, Nasmyth and colleagues (133) constructed a set of ∼300 strains, each deleted for a different sporulation-induced gene. Analyses of this collection have yielded more than 40 mutants with a variety of sporulation defects (27, 133). It is noteworthy, however, that, despite their regulated expression, deletion of most of these genes does not cause a detectable sporulation phenotype. Thus, sporulation-induced expression is not strongly correlated with an obvious sporulation function.

A GENETIC DESCRIPTION OF SPORE FORMATION

Beginning with the pioneering studies by Esposito and Esposito (38), more than 30 years of work has identified a large number of sporulation-defective mutants, some by directed screens and others by happenstance (40, 80). The identification and analysis of these mutants provide the basis for much of what is known about sporulation.

More recently, the construction of the yeast knockout collection has provided an invaluable new tool that allows the development of an even more comprehensive picture of the genes involved in sporulation. In addition to systematic screens of a collection of sporulation-induced genes (133) or a subset of the knockout collection (12), three different groups have used this resource to screen the homozygous diploid knockouts of all the nonessential yeast genes for sporulation defects. Importantly, each group has done the screening in a slightly different way. One such study screened the knockout collection directly in the light microscope for the presence of spores (36). A second screened the collection by using the microarray-based technique of phenotypic profiling (34, 152). In this analysis, sporulation was operationally defined as the acquisition of resistance to cell wall-degrading enzymes. The third study first crossed the knockout collection to a different genetic background, SK-1, which displays enhanced sporulation (92). Hybrid strains homozygous for each knockout were generated, and these strains were then screened visually for sporulation (92).

The result of these efforts is that we now have a much more complete picture of the genetic requirements for sporulation. Each of the these studies identified >200 mutants defective in sporulation. Perhaps not surprisingly given the different techniques and strain backgrounds involved, these mutants fall into three distinct but overlapping sets. Table 1 presents a list of the 289 genes identified in at least two of the three screens. Based on annotations available for each of these genes at the Saccharomyces Genome Database (www.yeastgenome.org), they have been divided in to five broad categories: (i) genes involved in mitochondrial/metabolic functions, (ii) vacuolar and autophagy genes, (iii) genes previously characterized as having premeiotic or meiotic defects, (iv) genes with known defects in prospore membrane or spore wall assembly, and (v) genes whose role in sporulation has not yet been defined.

TABLE 1.

Genes required for efficient sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

| Genes involved ina: | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondria/metabolism | Vacuole/autophagy | Meiosis/early sporulation | Spore formation | Unknown sporulation role | |||||

| Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF | Gene | ORF |

| ACS1 | YAL054c | AUT7 | YBL078c | SPO7 | YAL009w | GIP1 | YBR045c | ATS1 | YAL020c |

| PET112 | YBL080c | CCZ1 | YBR131w | MUM2 | YBR057c | SPO71 | YDR104c | CCR4 | YAL021c |

| COQ1 | YBR003w | APG12 | YBR217w | MMS4 | YBR098w | SWM1 | YDR260c | FUN12 | YAL035w |

| SCO1 | YBR037c | BPH1 | YCR032w | KAR4 | YCL055w | DIT1 | YDR403w | GPB2 | YAL056w |

| TPS1 | YBR126c | CVT17 | YCR068w | CSM1 | YCR086w | SPO73 | YER046w | YAL068c | |

| ADY2 | YCR010c | BRE1 | YDL074c | RAD57 | YDL059c | ISC10 | YER180c | NUP170 | YBL079w |

| SLM3 | YDL033c | VAM6 | YDL077c | RAD55 | YDR076w | SPO74 | YGL170c | HMT1 | YBR034c |

| MRPL1 | YDR116c | ATG9 | YDL149w | GSG1 | YDR108w | SPR3 | YGR059w | FAT1 | YBR041w |

| KGD2 | YDR148c | VPS41 | YDR080w | HPR1 | YDR138w | CRH1 | YGR189c | UBP14 | YBR058c |

| CBS2 | YDR197w | VPS52 | YDR484w | UME6 | YDR207c | AMA1 | YGR225w | RPL19A | YBR084c-a |

| TCM10 | YDR350c | VPS3 | YDR495c | RMD5 | YDR255c | NDT80 | YHR124w | YBR090c | |

| ATP17 | YDR377w | VAC8 | YEL013w | ZIP1 | YDR285w | CHS7 | YHR142w | SGF29 | YCL010c |

| SHE9 | YDR393W | PRB1 | YEL060c | EMI1 | YDR512c | SSP1 | YHR184w | THR4 | YCR053w |

| ACN9 | YDR511w | ATG18 | YFR021W | RAD51 | YER095w | ADY1 | YHR185c | SED4 | YCR067c |

| QCR7 | YDR529c | MON1 | YGL124c | DMC1 | YER179w | SPO14 | YKR031c | STP4 | YDL048c |

| RIP1 | YEL024w | ATG1 | YGL180w | RIM15 | YFL033c | SPO75 | YLL005c | YDL072c | |

| AFG3 | YER017c | VID30 | YGL227w | RMD8 | YFR048w | OSW2 | YLR054c | UFD2 | YDL190c |

| PET117 | YER058w | CLC1 | YGR167w | HOP2 | YGL033c | SEC22 | YLR268w | SNF3 | YDL194w |

| ICL1 | YER065c | PPA1 | YHR026w | SAE2 | YGL175c | CDA2 | YLR308w | GCS1 | YDL226c |

| PDA1 | YER178w | ATG7 | YHR171w | DOC1 | YGL240w | CHS5 | YLR330w | MAF1 | YDR005c |

| RMD9 | YGL107c | VPS53 | YJL029c | ZIP2 | YGL249w | SPO77 | YLR341w | CIS1 | YDR022c |

| MET13 | YGL125w | SNX4 | YJL036w | RMD11 | YHL023c | SMA2 | YML066c | YDR117c | |

| HAP2 | YGL237c | VPS25 | YJR102c | RIM4 | YHL024w | SPO20 | YMR017w | STB3 | YDR169c |

| SHY1 | YGR112w | VPS24 | YKL041w | RIM101 | YHL027w | MSO1 | YNR049c | CDC40 | YDR364c |

| YGR150c | VPS13 | YLL040c | NEM1 | YHR004c | SPO21 | YOL091w | RVS167 | YDR388w | |

| CBP4 | YGR174c | ATG10 | YLL042c | SPO13 | YHR014w | MPC54 | YOR177c | SAC7 | YDR389w |

| QCR9 | YGR183c | SNF7 | YLR025w | SAE3 | YHR079c-a | SSP2 | YOR242c | SPT3 | YDR392w |

| LSC2 | YGR244c | PEP3 | YLR148w | NAM8 | YHR086w | OSW1 | YOR255w | SSN2 | YDR443c |

| CBP2 | YHL038c | VPS36 | YLR417w | SPO12 | YHR152w | MUM3 | YOR298w | SNF1 | YDR477w |

| RRF1 | YHR038w | ATG17 | YLR423c | SPO16 | YHR153c | SMA1 | YPL027w | NPR2 | YEL062w |

| HTD2 | YHR067w | YPT7 | YML001w | MND2 | YIR025w | SPO19 | YPL130w | CKB1 | YGL019w |

| MSR1 | YHR091c | VPS20 | YMR077c | IME2 | YJL106w | SSO1 | YPL232w | SGF73 | YGL066w |

| YHR116w | ATG16 | YMR159c | IDS2 | YJL146w | SMK1 | YPR054w | ARC1 | YGL105w | |

| MRPL6 | YHR147c | ATG2 | YNL242w | IME1 | YJR094c | RTF1 | YGL244w | ||

| MDM31 | YHR194w | VPS27 | YNR006w | CST9 | YLR394w | PEX31 | YGR004w | ||

| PFK26 | YIL107c | AUT1 | YNR007c | RIM11 | YMR139w | BTN2 | YGR142w | ||

| KGD2 | YIL125w | PEP12 | YOR036w | RIM13 | YMR154c | GCN5 | YGR252w | ||

| YIL157c | VPS5 | YOR069w | SPO1 | YNL012w | ZUO1 | YGR285c | |||

| PET191 | YJR034w | SNF8 | YPL002c | MCK1 | YNL307c | PRS3 | YHL011c | ||

| NFU1 | YKL040c | ATG5 | YPL149w | EMI5 | YOL071w | ARD1 | YHR013c | ||

| MDH1 | YKL085w | ATG11 | YPR049c | MEI5 | YPL121c | YHR132w-a | |||

| CYT2 | YKL087c | VPS4 | YPR173c | REC8 | YPR007c | RPN10 | YHR200w | ||

| HAP4 | YKL109w | ATG13 | YPR185w | CLB5 | YPR120c | RPL34B | YIL052c | ||

| SDH1 | YKL148c | YIL060w | |||||||

| PCK1 | YKR097w | LAS21 | YJL062w | ||||||

| MMM1 | YLL006w | YJL160c | |||||||

| COX17 | YLL009c | YJR008w | |||||||

| SDH2 | YLL041c | YKL033w-a | |||||||

| MEF1 | YLR069c | YKL054c | |||||||

| CSF1 | YLR087c | NUP120 | YKL057c | ||||||

| MSS51 | YLR203c | MUD2 | YKL074c | ||||||

| YLR368w | CTK1 | YKL139w | |||||||

| FBP1 | YLR377c | CBT1 | YKL208w | ||||||

| NAM2 | YLR382c | DOA1 | YKL213c | ||||||

| PIF1 | YML061c | YKR089c | |||||||

| ATP18 | YML081c-a | YLL033w | |||||||

| NDI1 | YML120c | UBI4 | YLL039c | ||||||

| RSF1 | YMR030w | AAT2 | YLR027c | ||||||

| PET111 | YMR257c | IES3 | YLR052w | ||||||

| PPA2 | YMR267w | YLR149c | |||||||

| CAT8 | YMR280c | DCS1 | YLR270w | ||||||

| AEP2 | YMR282c | HMG2 | YLR450w | ||||||

| MRPL33 | YMR286w | GSF2 | YML048w | ||||||

| MSU1 | YMR287c | YMR010w | |||||||

| COX5A | YNL052w | SRT1 | YMR101c | ||||||

| MLS1 | YNL117w | STO1 | YMR125w | ||||||

| ATP11 | YNL315c | YMR196w | |||||||

| COQ2 | YNR041c | SSN8 | YNL025c | ||||||

| PET494 | YNR045w | WHI3 | YNL197c | ||||||

| IFM1 | YOL023w | CAF40 | YNL288w | ||||||

| MDH2 | YOL126c | POP2 | YNR052c | ||||||

| CYT1 | YOR065w | SIN3 | YOL004w | ||||||

| CAT5 | YOR125c | YOR008c-a | |||||||

| IDH2 | YOR136w | WHI5 | YOR083w | ||||||

| LSC1 | YOR142w | LEO1 | YOR123w | ||||||

| MRPL23 | YOR150w | RIS1 | YOR191w | ||||||

| PET123 | YOR158w | YOR291w | |||||||

| LIP5 | YOR196c | SSN3 | YPL042w | ||||||

| HAP5 | YOR358w | LGE1 | YPL055c | ||||||

| MRPS16 | YPL013c | TGS1 | YPL157w | ||||||

| LPE10 | YPL060w | YPL166w | |||||||

| MSD1 | YPL104w | CBC2 | YPL178w | ||||||

| MRP51 | YPL118w | YPL208w | |||||||

| COX10 | YPL172c | UBA3 | YPR066w | ||||||

| MRPL40 | YPL173w | ||||||||

| CBP3 | YPL215w |

The majority of sporulation-defective mutants arrest prior to the meiotic divisions (36). Mutants in the first three categories above all fall into this class. Because it occurs in the presence of a nonfermentable carbon source, sporulation is an obligatorily aerobic process, and respiratory-incompetent yeast cells arrest upon transfer to sporulation medium (110, 169). This is the reason for the large number of genes with known mitochondrial functions listed in the first group in Table 1. Similarly, because sporulation takes place in the absence of a nitrogen source, during this process all the amino acids used for new protein synthesis must be scavenged by recycling of preexisting proteins. The repeated identification of many genes involved in delivery of proteins to the vacuole or in autophagy (second group in Table 1), which are necessary for protein recycling, is consistent with insufficient amino acid availability blocking entry into the meiotic divisions. Included in the third group of genes are many required for proper chromosome segregation during meiosis as well as transcription factors required for the induction of early genes.

The fourth, and smallest, group of genes are those known to be required for assembly of the spore per se. The majority of these genes are induced by Ndt80p at the onset of meiosis I (25, 130). The functions of many of them will be described in detail below. Finally, the fifth group consists of another 80 genes whose roles in sporulation have yet to be determined. While this group includes genes with various functions, it is noteworthy that a large fraction (∼30%) appear to involved in gene expression as subunits of either chromatin remodeling or mRNA processing complexes. Many of these genes may, therefore, be involved in regulation of meiotic gene expression.

Even this large list is does not present a comprehensive picture of the genes required for sporulation. Essential genes were not assayed in any of the genomic screens, and many are likely to be required for sporulation. Moreover, because of the nature of the assays involved, mutations that make visible but inviable spores, such as mutants defective in meiotic chromosome segregation, are absent from the list in Table 1. Similarly, mutants that form defective but visible spore walls, such as those with outer spore wall defects (see below), are underrepresented in the two visual screens. Nonetheless, these studies have provided us with a broad overview of the genetic requirements for spore formation. The remainder of this review will focus on the cellular events involved in formation of spores and the genes known to participate in these events.

TO MAKE A SPORE

The process of spore construction requires two events in which cellular structures are assembled de novo. First, prospore membranes must be generated around the daughter nuclei to create prospores. Second, the resulting prospores must be surrounded by a protective spore wall. These events will be considered in turn.

Formation and Growth of the Prospore Membrane

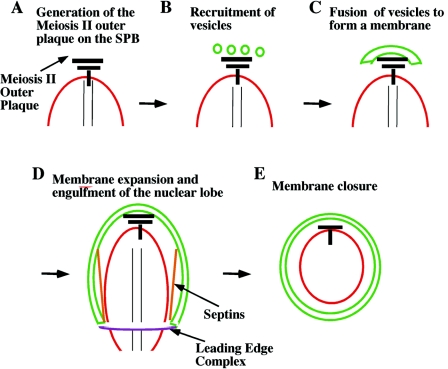

The formation and growth of the prospore membrane occur in several steps (Fig. 2). Initially, the SPB is modified to allow its cytoplasmic surface to act as a site for the homotypic fusion of secretory vesicles into a membrane sheet (4, 31, 76) (Fig. 2A to C). A specialized SNARE complex is then required for the fusion event itself (104). After the initial formation of a membrane cap on the SPB, the membrane continues to grow by vesicle addition. During membrane expansion, membrane-associated complexes are required properly shape the membrane so that its growth is properly constrained and ultimately leads to nuclear capture (Fig. 2D and E). The details of these different steps in membrane formation are described below.

FIG. 2.

Stages of prospore membrane growth. (A) As cells enter meiosis II, the meiosis II outer plaque is formed on the cytoplasmic face of the SPB (black bar). (B and C) The meiosis II outer plaque becomes a site for the recruitment and subsequent fusion of secretory vesicles to form a prospore membrane (green). (D) As the prospore membrane expands to engulf a daughter nucleus, its growth is controlled by two membrane-associated complexes: the septins (orange), which form sheets thought to run down the nuclear-proximal side of the prospore membrane, and the leading-edge complex (purple), which forms a ring structure at the membrane lip. (E) Closure of the prospore membrane completes cytokinesis. All three of the prospore membrane-associated complexes, i.e., the septins, leading-edge complex, and meiosis II outer plaque, disassemble at about the time of prospore membrane closure.

Modification of the SPB.

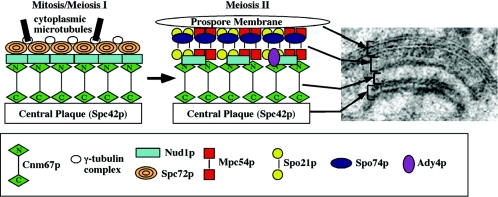

The SPB is the sole microtubule-organizing center in an S. cerevisiae cell and spans the nuclear envelope so that it has distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic faces (67). The SPB is a multilaminar structure with a nuclear face, or inner plaque, from which spindle microtubules are nucleated; a central plaque, which contains the Spc42 protein, spanning the nuclear envelope; and a cytoplasmic face, or outer plaque, which is the organizing center for cytoplasmic microtubules (Fig. 3). In vegetative cells, the outer plaque consists primarily of three proteins, Cnm67p, Nud1p, and Spc72p (183). Spc72p acts a receptor for the gamma-tubulin complex, anchoring cytoplasmic microtubules to the SPB (75).

FIG. 3.

Organization of proteins within the meiosis II outer plaque. The changes in organization and composition between a mitotic/meiosis I outer plaque and a meiosis II outer plaque are shown in the cartoon. The Spc72p and γ-tubulin complex proteins are removed and replaced with Ady4p, Mpc54p, Spo21p, and Spo74p, leading to a conversion from microtubule to membrane nucleating activity. In the upper right is shown an electron micrograph of a meiosis II outer plaque with associated prospore membrane. The proposed correspondence between the arrangement of proteins in the model and the structure as seen in the electron micrograph is indicated.

At the onset of meiosis II, Spc72p is lost from the cytoplasmic face of the SPB and replaced by a several meiosis-specific proteins, which together make up the meiosis II outer plaque (76, 113) (Fig. 3). This change in composition converts the function of the cytoplasmic face of the SPB from microtubule nucleation to membrane nucleation. The meiosis II outer plaque is the site of formation of the prospore membrane (52, 100). Early work established a correlation between the number of SPBs displaying an outer plaque and the number of prospore membranes formed, suggesting that the meiosis II outer plaque is essential for prospore membrane formation (31). More recently, several gene products that are components of this structure have been identified. The first of these was Cnm67p, a coiled-coil protein that is present on the vegetative SPB outer plaque (10, 183). The original study noted that cnm67 homozygous mutants fail to sporulate, suggesting that Cnm67p is also required for assembly of the meiosis II outer plaque, a prediction that was subsequently confirmed (4, 10). Of the other identified components of the vegetative outer plaque, only Nud1p is also present in outer plaques in meiosis II (76). The remaining genes known to encode components of this structure are meiosis specific in their expression. These are MPC54, MPC70/SPO21, SPO74, and ADY4 (4, 76, 113).

Figure 3 shows the proposed arrangement of these proteins within the meiosis II outer plaque (76, 113). The large electron density that is in contact with the prospore membrane is composed of the Mpc54, Spo21, and Spo74 proteins. Two of these proteins, Spo21p and Mpc54p, contain predicted coiled-coil domains, while Spo74p is globular (4, 76, 113). By analogy to areas of lower electron density in other parts of the SPB (149), the lower density in the middle of the Mpc54p/Spo21p/Spo74p region is thought to be the coiled-coil regions of the Mpc54 and Spo21 proteins (Fig. 3). Individual deletion of any of these three genes produces a common phenotype: the outer plaque structure is ablated, and no prospore membrane forms (4, 76, 113). Thus, assembly of the outermost layers of the plaque requires all three components, and, as inferred in the earlier studies, this structure is essential for the coalescence of vesicles into a prospore membrane.

The Nud1 and Ady4 proteins are thought to reside on the inner side of the Mpc54p/Spo21p/Spo74p complex (Fig. 3) (113). Nud1p is also present in vegetative outer plaques, where it serves as the SPB anchor for Spc72p and for components of the mitotic exit network (51). The function of Nud1p at the SPB during sporulation has not been described. Ady4p appears to be a minor component of the meiotic SPB. Though not essential for formation of the meiosis II outer plaque, it is important for stability of the structure. In ady4 mutants a fraction of the outer plaques appear to disassemble during meiosis II, leading to the failure of some prospore membranes to package nuclei and the production of asci with fewer than four spores (113).

The large area of low density between the outer plaque and the central plaque has been demonstrated in vegetative cells to correspond to the coiled-coil domain of Cnm67p (149) (Fig. 3). It is thought that Cnm67p also links the central plaque to the outer plaque in the meiotic SPB (4). The particular importance of the meiosis II outer plaque in allowing membrane formation is shown by the distinct phenotype of cnm67 mutants during sporulation (4). In cnm67 cells, no outer plaque structures are seen at the SPB; in fact, even less residual electron density is present than in mpc54, spo21, or spo74 mutants. Unlike these other mutants, a fraction of cnm67 cells do form prospore membranes; however, these membranes are not anchored to the SPB and fail to capture nuclei. This ectopic formation of prospore membranes is proposed to result from the formation of MPC54/SPO21/SPO74 complexes that are not anchored to the rest of the SPB, an interpretation supported by the observation that ectopic membranes are absent in a cnm67 spo21 double mutant (4).

The identification of multiple components of the meiosis II outer plaque has led to the demonstration that this structure is essential both for the coalescence of vesicles into a prospore membrane and to anchor that membrane to the nucleus and facilitate nuclear capture. The mechanisms by which this structure binds to the membrane and promotes fusion remain unknown. However, as described in the next section, the critical role of the meiosis II outer plaque in membrane formation allows the cell to regulate spore formation by regulating this modification of the SPB.

(i) Regulation of SPB assembly by carbon availability.

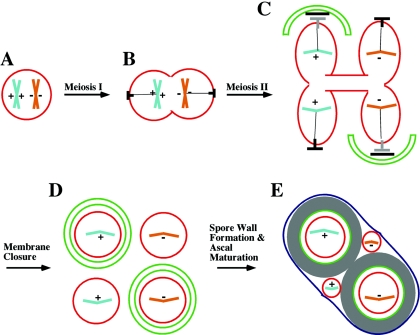

Sporulation of diploid cells occurs in response to starvation conditions, specifically the absence of nitrogen and the presence of a nonfermentable carbon source such as acetate. In a seminal study, Davidow et al. (31) defined a secondary response to the depletion of the carbon source during the process of sporulation, the formation of a particular form of two-spored ascus or dyad. Using a strain background that was temperature sensitive for progression out of meiotic prophase, the authors found that the strain could be held in prophase by incubation at 37°C and that when released by transfer to lower temperature, it proceeded through meiosis and sporulated. If the strain was held at 37°C for up to 24 h, it formed tetrads upon a shift to lower temperature. However, when the temperature was lowered after arrest for greater than 24 h, the cells predominantly formed dyads. Dissection and analysis of marker genes segregating in the dyads revealed that the spores were viable and haploid. Moreover, for heterozygous markers that were tightly centromere linked, there was always one spore of each genotype. That is, the chromosomes present in the two spores were homologues, not sister chromatids. This segregation pattern distinguished these dyads from other mutants that form dyads of two haploid spores in which centromeric markers segregate randomly or dyads which contain two diploid spores (73, 173). Because of the chromosome segregation pattern, these dyads were termed nonsister dyads (NSDs). An outline of NSD formation is shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Nonsister dyad formation. (A to C) During the first meiotic division, homologous chromosomes segregate to opposite poles, and at the second meiotic division, sister chromatids are separated. (C) When sporulated under acetate-depleted conditions, only two of the fours SPBs, one from each spindle, form meiosis II outer plaques. (D) As a result, only two prospore membranes are formed and only two nuclei are packaged into spores. (E) The unpackaged nuclei degenerate during ascal maturation, resulting in a two-spored ascus. If a heterozygous centromere-linked marker (indicated by + and −) is followed, an NSD will contain one spore with each allele. The gray ⟂︁ indicates the daughter SPB formed at meiosis II (see text).

Two critical features of NSD formation were elucidated in this study. First, it was shown that the switch from tetrads to NSDs is triggered by the depletion of acetate from the medium. This suggests that NSD formation is a regulated response to carbon depletion. In fact, a subsequent study found that transfer of cells from sporulation medium to water prior to meiosis I could trigger the same phenomenon (158). Second, in cells forming NSDs, the basis for the formation of two spores was shown to be that only two of the four SPBs, one on each of the two meiosis II spindles, are modified on their outer plaque. As a consequence, only two prospore membranes form and, therefore, only two spores. Because one pole from each spindle is modified, the resulting spores will contain centromeres from homologous chromosomes, which separate from each other at the first meiotic division (Fig. 4). Thus, NSD formation is a conservation mechanism that allows a cell that is committed to sporulation to save resources by reducing the number of daughter cells it will form. Moreover, this reduction results from the regulation of SPB modification in response to carbon availability. This regulated change in SPB modification will be referred to as the NSD response.

Subsequent studies identified two mutants that formed NSDs at high frequency even under conditions where acetate was plentiful (33, 115). The first of these mutant genes, _hfd1_-1, has been lost (T. Iino, personal communication). The second, ady1, encodes a nucleus-localized protein that triggers NSD formation by causing only two of the four SPBs to be modified, similar to the metabolic response (33). Although the molecular function of ADY1 remains unknown, it may play a role in SPB modification in response to carbon limitation.

A third mutant condition that causes NSD formation is haplo-insufficiency of outer plaque components. Strains heterozygous for a deletion of SPO21, SPO74, or MPC54 form a high percentage of NSDs under conditions where wild-type cells would form tetrads (4, 113, 181; A. M. Neiman, unpublished observations). Additionally, a particular allele of the central plaque component gene SPC42 has been reported to increase NSD formation (62). Not all mutations affecting the SPB lead to this phenotype, however, as cnm67 heterozygotes form tetrads and ady4 homozygotes form random, rather than nonsister, dyads (A. M. Neiman and M. Nickas, unpublished observations) (113). The consistent pattern that emerges from these studies is that decreasing the abundance of any one of the outermost components of the meiosis II outer plaque leads to formation of NSDs.

The studies described above suggested that SPO21, SPO74, and/or MPC54 might be a regulatory target of the NSD response. Direct observation of the localization of these three proteins in cells undergoing the NSD response revealed that Spo74p and Spo21p are absent from two of the four spindle poles during meiosis II but that Mpc54p and the other outer plaque components are still found predominantly on all four SPBs (111). Thus, localization of Spo74p and Spo21p to the SPB seems to be regulated in response to carbon availability. Under normal conditions, these two proteins are interdependent for localization to the SPB: Spo74p does not localize to spindle poles in a spo21 mutant and vice versa, so regulation of either one of the proteins would account for the effects seen (113).

(ii) Asymmetric control of mother and daughter SPBs during sporulation.

How the localization of Spo21p and Spo74p to the pole is regulated during NSD response remains an open question, but some insight into this issue was afforded by the identification of which SPBs these proteins are recruited to (or excluded from) during the NSD response. At the meiosis I/meiosis II transition, the two SPBs present during meiosis I duplicate to form the two poles of each meiosis II spindle so that each meiosis II spindle contains a mother pole and daughter pole (Fig. 4). During mitotic growth, the asymmetric localization of the Kar9 protein to the mother, but not daughter, poles is important for proper orientation of the mitotic spindle and for nuclear segregation into the bud (88, 127). KAR9 plays no obvious role in sporulation (36), but, by analogy, formation of NSDs could be explained if the mother and daughter poles are distinct in their capacity to form meiosis II outer plaques under NSD conditions.

By using an Spc42 fusion protein that specifically marks the older, mother SPBs (127), it was shown that during the NSD response the Spo21 and Spo74 proteins are found almost exclusively on the daughter SPBs in meiosis II, indicating that NSDs are formed by modification of only the daughter SPBs (Fig. 4) (111). Remarkably, when NSDs are triggered by haplo-insufficiency of spo21, it is again only the daughter SPBs that get modified (M. Nickas and A. M. Neiman, unpublished observations). While the molecular mechanisms at work remain to be elucidated, these results allow a more precise description of the phenomenon: the depletion of the carbon source during the process of sporulation leads to a failure to recruit the Spo74 and Spo21 proteins to the mother SPBs. Any model describing these events must account for the fact that simply lowering the amount of these proteins is sufficient to generate the asymmetric use of the mother and daughter SPBs. One proposed explanation is that at the meiosis I/meiosis II transition the daughter SPBs are modified—that is, assemble membrane-organizing outer plaques—before the mother SPBs (111). This may be because the mother SPBs have a preexisting microtubule-nucleating outer plaque that must be rearranged. If the outer plaque components are limiting, the daughter SPBs use up the available pool and so the mother SPBs are not modified. If assembly of the outer plaque structure was highly cooperative, then limitation of any one of the components would cause this effect. This model can account for the haplo-insufficient phenotype of mpc54, spo21, or spo74 mutants and suggests that limiting expression of SPO21 and or SPO74 could be the basis for regulation by carbon depletion. Though appealingly simple, this proposal has yet to be rigorously tested. Much remains to be learned about the regulatory mechanisms governing assembly of this membrane-organizing center.

(iii) An intermediary metabolite regulates SPB modification.

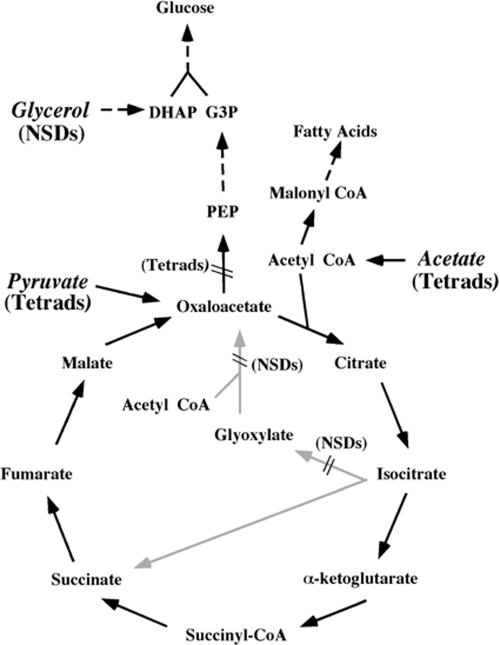

The original description of the NSD response demonstrated that depletion of acetate from the medium triggered this response (31). What remained unclear was whether the cell was responding directly to the disappearance of acetate or perhaps to the absence of some downstream product of acetate metabolism. In sporulation medium, acetate is used by the cell as both the energy source and the source of structural carbon for biosynthesis of macromolecules (39). The metabolic pathways of acetate usage are summarized in Fig. 5. For ATP generation, acetate is converted to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and oxidized in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to generate reducing equivalents for oxidative phosphorylation (157). For biosynthetic purposes, the acetyl-CoA must feed into synthesis of lipids, nucleotides, and polysaccharides (there is no net synthesis of amino acids during sporulation because of the absence of a nitrogen source) (129, 137, 157). Carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA provides the building blocks for lipid biosynthesis. However, nucleotide synthesis for DNA replication and synthesis of the polysaccharide layers of the spore wall require that the acetate first be converted into glucose (129). Gluconeogenesis consumes two molecules of the TCA cycle intermediate oxaloacetate for each glucose molecule produced. Oxaloacetate is also required as a catalytic intermediate in the TCA cycle. To prevent gluconeogenic consumption of oxaloacetate from interfering with oxidation of acetyl-CoA, the yeast cell generates oxaloacetate via the glyoxylate cycle (77, 157) (Fig. 5). The glyoxylate cycle consumes two acetyl-CoA molecules and produces a molecule of succinate without donating electrons to the electron transport chain. Succinate is then oxidized to oxaloacetate and provides the starting point for gluconeogenesis. It should be noted that many of the glyoxylate cycle enzymes are located in different cellular compartments from the analogous TCA cycle enzymes, and it is a cytoplasmic pool of oxaloacetate that is used for gluconeogenesis as opposed to the oxaloacetate that functions in the TCA cycle, which is located in the mitochondrial matrix (59, 87, 90, 96, 159).

FIG. 5.

Pathways of acetate metabolism in sporulating cells. Carbon sources mentioned in the text are shown in italic, and whether cells form tetrads or NSDs when sporulated on those carbon sources is indicated. Positions at which mutations in the glyoxylate cycle or gluconeogenesis lead to NSD or tetrad formation in the presence of acetate are also indicated. Gray arrows denote metabolic reactions unique to the glyoxylate cycle. Dashed lines indicate multiple reactions. DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate. G3P, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

If a product of acetate metabolism is used by the cell to detect the availability of the environmental carbon source, then blocks in acetate metabolism might lead to the formation of NSDs even in the presence of acetate. This “sensor metabolite” could be an end product of acetate metabolism, such as glucose or ATP, or an intermediate in acetate usage. Strikingly, when mutants blocked in the glyoxylate cycle or the subsequent conversion of succinate to fumarate were sporulated in acetate, about 50% of the cells formed NSDs, indicating that these cells were undergoing the NSD response (111). These mutations do not effect the TCA cycle or ATP generation, and therefore these results implicate a downstream product of the glyoxylate cycle as the sensor metabolite. By contrast, mutations that block the committed steps of gluconeogenesis did not cause NSD production (111). These results suggest that the sensor metabolite is produced even when gluconeogenesis is blocked. Together these genetic tests map the sensor to one of three metabolites: fumarate, malate, or oxaloacetate (Fig. 5).

Further support for the idea that one of these three molecules is used by the cell as a carbon sensor was provided by changing the carbon source for sporulation. Sporulation on pyruvate as the principal carbon source restored tetrad formation to the glyoxylate cycle mutants. This suggests that the sensor intermediate is produced from pyruvate. To feed gluconeogenesis, pyruvate is converted directly to oxaloacetate, bypassing the need for the glyoxylate cycle (Fig. 5). Thus, these experiments suggest that a cytoplasmic pool of oxaloacetate (or some derivative) is the sensor intermediate. Consistent with this interpretation, when wild-type cells are sporulated on glycerol as the sole carbon source, they form almost exclusively NSDs (111). The conversion of glycerol to glucose, or its conversion to acetyl-CoA for oxidation in the TCA cycle, never requires the generation of cytoplasmic oxaloacetate (Fig. 5). Thus, under these conditions, even though the cell has ample carbon available to meet both its energy and biosynthetic needs, it behaves as though carbon were limiting.

In sum, the NSD response allows the cell to conserve resources when it has committed to meiosis and sporulation but environmental conditions may not support the formation of four daughter cells. As cells sporulate in acetate, increased flux through the glyoxylate pathway generates a increase in the cytoplasmic pool of oxaloacetate. By a mechanism yet to be explained, the presence of oxaloacetate is measured by the cell as an indicator of the available biosynthetic carbon pool. If sufficient oxaloacetate is present, the cell modifies all four spindle pole bodies and a tetrad is formed. If oxaloacetate is not present, then Spo21p and Spo74p are not recruited to the mother SPBs and NSDs are formed. It is interesting that the NSD/tetrad decision appears to be tuned to an intermediate in acetate metabolism. Studies of sporulation on different carbon sources demonstrated that acetate is the preferred carbon source for sporulation (95). Acetic acid-producing bacteria and yeasts are major components of the microbial flora that grow on broken grapes (43). It is tempting to speculate that in nature S. cerevisiae grows in competition with acetate-producing bacteria and, therefore, that acetate is the carbon source most likely to be present at times of nitrogen depletion. Perhaps for this reason S. cerevisiae has tuned its sporulation program to respond to acetate levels.

Initial formation of the prospore membrane.

Once the meiosis II outer plaque has assembled, it becomes a site for the docking of precursor vesicles for the prospore membrane (104). These vesicles are post-Golgi vesicles that carry proteins destined for an extracellular compartment and are analogous to secretory vesicles in vegetative cells (106). Furthermore, the fusion of these vesicles requires many of the same proteins necessary for fusion of secretory vesicles at the plasma membrane (106). In contrast to secretory vesicles in vegetative cells, which are delivered to the periphery along actin cables (132), in sporulating cells vesicles are delivered initially to the spindle poles and then to the growing prospore membrane. Several lines of evidence suggest that actin does not play a critical role in vesicle delivery during sporulation. Mutations of many actin-organizing proteins that disrupt vesicle delivery in vegetative cells, as well as mutations of the ACT1 gene itself, do not significantly affect sporulation efficiency (34, 36, 92, 182). Moreover, while treatment of sporulating cells with the actin-depolymerizing drug Latrunculin A blocks sporulation, it does not inhibit prospore membrane growth (A. Coluccio and A. M. Neiman, unpublished observations). Taken together, these observations suggest that actin-based transport does not play a critical role in this process. Delivery apparently does not require cytoplasmic microtubules, which are absent by this stage of sporulation due to the changes in the SPB. The mechanism of vesicle delivery to the prospore membrane is unknown and remains an important challenge in our understanding of the process.

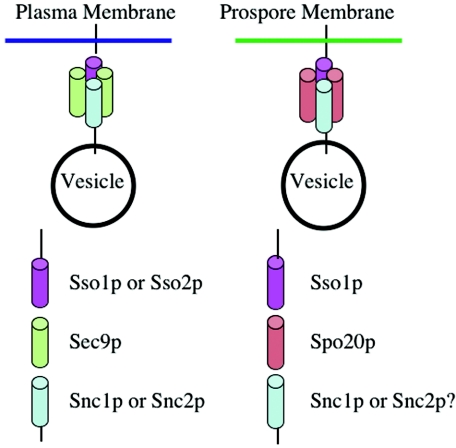

In addition to this change in vesicle delivery, the fusion of vesicles with the prospore membrane has different genetic requirements than fusion of vesicles with the plasma membrane. After secretory vesicles are delivered to the plasma membrane, the fusion of the vesicle membrane and the plasma membrane is then mediated by a heterotrimeric SNARE complex (141). Analogous SNARE complexes function for each fusion event in the secretory pathway, and much of the specificity of vesicle/target membrane interactions that is required for proper trafficking through the secretory pathway is thought to be based on cognate interactions between SNARE proteins (123, 124, 142). SNARE complexes are based on the formation of a four-helix bundle between different subunits of the hetero-oligomer (162). Three of the helices are provided by proteins associated with the target membrane (the t-SNAREs) and one is provided by a protein on the surface of the vesicle (the v-SNARE). The v-SNARE and at least one of the t-SNARE proteins are transmembrane proteins, and assembly of the bundle drives these transmembrane domains together, possibly leading directly to the fusion of the two lipid bilayers (180).

For fusion of vesicles with the plasma membrane, the t-SNARE consists of the Sso1 or Sso2 protein, which are redundant for this purpose, in partnership with the Sec9 protein (1, 11). Sso1p or Sso2p provides the transmembrane domain and one helix of the oligomer, whereas Sec9p is a peripheral membrane protein that provides two helices. The v-SNARE is encoded by a second redundant pair of genes, SNC1 and SNC2 (131). The first genetic distinction between vesicle fusion at the plasma membrane or prospore membrane was the finding that the t-SNARE SEC9 was dispensable for sporulation (106). During sporulation, Sec9p is replaced by the related, sporulation-specific Spo20 protein. Although Spo20p and Sec9p are homologous, they are largely distinct in their sites of action. Ectopic expression of SPO20 in vegetative cells cannot rescue the growth defect of a _sec9_-ts mutant, nor can expression of SEC9 under the SPO20 promoter rescue the sporulation defect in a spo20 cell (106). However, there is some overlap of function in sporulation, as a spo20 single mutant produces abnormal prospore membranes whereas a _spo20 sec9_-ts mutant displays no prospore membranes at all, suggesting that SEC9 is capable of supporting at least abortive prospore membrane assembly (106). In chimera studies, the major determinant of sporulation function of Spo20p mapped to an amino-terminal region outside of the domain in which it is homologous to Sec9p (107).

Also indicative of the close relationship between Sec9p and Spo20p, both bind in vitro to the Sso1 protein and can form ternary complexes with Sso1p and Snc2p with similar efficiency (107). Indirect immunofluorescence using polyclonal antibodies to the Sso and Snc proteins demonstrated that these SNAREs localize to the prospore membrane. Based on these observations, the change in fusion functions between the plasma membrane and the prospore membrane was proposed to be a switch in one subunit of the SNARE complex, an exchange between Spo20p and Sec9p (107).

However, the requirements for vesicle fusion at the prospore membrane are more complicated than this initial picture, as there is further specialization of the SNARE complex (Fig. 6). A study of sso1 mutants revealed that an sso1 single mutant, which has no strong vegetative phenotype, is completely defective in sporulation (66). The sso1 phenotype could not be rescued by overexpression of SSO2. A subsequent chimera study suggested that the specificity of SSO1 for sporulation lay partly in its amino-terminal region (the only region of the proteins with significant sequence divergence) and, surprisingly, in the 3′ untranslated region of the SSO1 gene (119). The 3′ untranslated region did not seem to have a significant effect on the levels of the Sso1 protein, so the basis for this effect remains mysterious. An examination of the sporulation defect in sso1 cells revealed that prospore membranes are absent in the mutant, indicating that SSO1 is required for the fusion of vesicles to form a prospore membrane (H. Nakanishi and A. M. Neiman, unpublished data). Thus, Sso1p and Sso2p are redundant for fusion at the plasma membrane, but only Sso1p can function during fusion at the prospore membrane.

FIG. 6.

Specific SNARE complexes mediate fusion with the plasma membrane and prospore membrane. Secretory vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane is mediated by a heterotrimer consisting of Sso1p or Sso2p, Sec9p, and Snc1p or Snc2p (left panel). At the prospore membrane the fusion of secretory vesicles requires Sso1p, Spo20p (although Sec9p can substitute to a limited extent), and probably Snc1p or Snc2p. The roles of Snc1p and Snc2p in this process are inferred from the protein localization but have not been directly demonstrated (107).

Studies of the lipid-modifying enzyme phospholipase D suggest that changes in lipid composition are also important for assembly of the prospore membrane (143). This enzyme, which hydrolyzes the choline head group of phosphatidylcholine to produce phosphatidic acid, is encoded by the SPO14 gene, and the Spo14 protein is localized to the prospore membrane during sporulation (140, 143). Originally identified on the basis of its sporulation defect, this gene is transcribed in both vegetative and sporulating cells, but deletion of the gene has significant phenotypes only during sporulation. Deletion of SPO14 leads to a failure to form prospore membranes (143). Prospore membranes are also absent in cells expressing a point mutation in SPO14 that encodes a catalytically inactive protein, indicating that enzyme activity is critical for function (143). In the presence of 1-butanol, phospholipase D will convert phosphatidylcholine into choline and phosphatidylbutanol rather than phosphatidic acid. Addition of 1-butanol, but not 2-butanol, to sporulation medium blocks sporulation (144). Together these results indicate that it is the production of phosphatidic acid rather than the turnover of phosphatidylcholine which is in some way critical for membrane assembly (144).

One role for Spo14-generated phosphatidic acid in prospore membrane formation may be in enhancing the activity of Spo20p. As noted earlier, the amino-terminal domain of Spo20p contains a region crucial for the function of this protein at the prospore membrane (103). This crucial “activating” function is a lipid binding domain that can bind to phosphatidic acid and is essential for localization of the Spo20p in vivo (103). Moreover, translocation of Spo14p to the plasma membrane in vegetative cells, an arrangement analogous to that on the prospore membrane, allows Spo20p to replace Sec9p for fusion of vesicles at the plasma membrane (28). This is true even for derivatives of Spo20p that lack the phosphatidic acid binding domain. However, the phenotype of a spo14 mutant is more extreme than that of a spo20 mutant (106, 143). Therefore, although SPO14 may be important for the function of Spo20p-containing SNAREs, phosphatidic acid may play additional roles in prospore membrane assembly as well. Deciphering the interaction between SNARE specificity and lipid composition during fusion at the prospore membrane is an important challenge that will shed light more generally on how the specificity of fusion is regulated in the secretory pathway.

Membrane expansion.

Once an initial membrane cap has been established by fusion of vesicles on the SPB, the membrane grows to engulf the nuclear lobe by continued vesicle fusion. The growth of the membrane must be controlled so that it obtains the proper shape and dimensions to enclose a nucleus. These events require several additional genes that are not necessary for the membrane fusion per se (101, 133, 163). While the functions of most of these genes are not known, two membrane-associated complexes that are implicated in the control of membrane expansion have been identified: the septins and the leading-edge complex.

(i) Septins.

Septins are a conserved family of filament-forming proteins (72). In vegetative cells, five distinct septin proteins, Cdc3, Cdc10, Cdc11, Cdc12, and Sep7, form a ring structure at the bud neck (48, 89). The septin ring plays a variety of important roles as a scaffold for the organization of complexes involved in cytokinesis, cell wall deposition, and cell cycle regulation (48, 89). In addition, the septin ring appears to form a diffusion barrier that aids in differentiating the bud from the mother cell (5). In sporulating cells, septin rings on the cell plasma membrane are disassembled and the septins relocalized to the forming prospore membrane (41).

At least three and possibly all five of the septins found in septin rings are localized to the prospore membrane, and two of the genes, CDC3 and CDC10, are strongly upregulated by Ndt80p in mid-sporulation (25, 68, 89). In addition, two sporulation-specific septin proteins, Spr3p and Spr28p, are also found in the prospore membrane-associated septin structures. Several lines of evidence suggest that the organization of the septins on the prospore membrane is distinct from that in the septin ring. First, while the septin ring in vegetative cells is a relatively static structure, during sporulation the septins move as the prospore membrane expands (35, 41). Second, their arrangement on the prospore membrane is different than that at the bud neck. By immunofluorescence, the septins appear first to be organized as rings near the SPB when prospore membranes are small and then to expand into a pair of bars that run parallel to the long axis of the prospore membrane as the membrane expands (Fig. 2) (41). Three-dimensional reconstructions reveal these bars to be a pair of sheets running on opposite sides of the membrane (163). Moreover, these sheets contain the Spr3 and Spr28 proteins, which cannot be incorporated into the septin ring when expressed in vegetative cells (41; H. Tachikawa, personal communication). Finally, in vegetative cells mutation of any one septin (all except for SEP7) leads to the disappearance of bud neck rings. By contrast, mutation of individual septins, or even an spr3 spr28 cdc10 triple mutation, has no strong effect on the ability of the other septins to organize on the prospore membrane (35, 41; A. M. Neiman, unpublished observations). Thus, the organization of these filaments may be distinct in sporulating cells.

What is the role of the septins in spore formation? Not only does mutation of one or multiple septins during sporulation not disrupt the localization of the other septins, the mutants do not have a strong sporulation phenotype (35, 41; A. M. Neiman, unpublished observations). This suggests that if, as implied by their localization pattern, the septins play an important role in spore formation, then they must function redundantly in this process. Analogous to their role in vegetative cells, the septins may help to localize other proteins to specific areas of the prospore membrane, for example, the Gip1 protein. GIP1 encodes a sporulation-specific regulatory subunit of the Glc7 protein phosphatase (170). During sporulation, Gip1p and Glc7p colocalize with the septins throughout prospore membrane formation (163). Mutation of gip1 or alleles of glc7 that cannot interact with Gip1p leads to the failure of septins to localize to the prospore membrane, indicating that these proteins both organize and may be part of the septin complex (163).

Because gip1 mutants lack organized septins, the phenotype of the mutant may provide some insight into the role of septins in spore formation. In fact, prospore membrane formation is largely normal in gip1 mutants. Four membranes are formed per cell, and these membranes, though they appear slightly smaller than in wild-type cells, capture nuclei efficiently (163). The most striking defect in gip1 mutants appears to be in triggering the assembly of the spore wall in response to closure of the prospore membrane. Whether this phenotype is due to the absence of organized septins or the absence of an independent function of GIP1 remains to be determined, but the phenotype of gip1 raises the possibility that septins may be involved in monitoring membrane growth and closure rather than in controlling membrane growth.

(ii) The leading-edge complex.

Electron micrographs reveal an electron-dense coat, termed the leading-edge complex, located at the lip of each growing prospore membrane (21, 25, 76, 101). Three components of this coat have been identified: Ssp1p, Ady3p, and Don1p (101, 112). Localization of these proteins by immunofluorescence and green fluorescent protein tagging confirms that they form a ring structure at the mouth of the growing prospore membrane (101, 112). SSP1 and DON1 were originally identified on the basis of their sporulation-specific expression (101, 102). ADY3, by contrast, was identified by its ability to bind to meiotic SPB components in both two-hybrid and copurification studies (63, 101, 171). At early times of prospore membrane assembly, Ady3p is found on the SPB, whereas the other two subunits are localized in a punctate pattern in the cytosol, suggesting an association with transport vesicles (101). As the vesicles coalesce into a membrane, all three proteins can be found at the SPB. It has been suggested that this pattern of localization indicates a role for these proteins in the recruitment of vesicles to the SPB (101). As the prospore membrane expands, the localization patterns of the three proteins resolve into a ring structure that remains associated with the leading edge of the prospore membrane (Fig. 2). This structure is distinct from the septin sheets described above. Double-labeling studies indicate that the septins run backwards from the leading edge towards the SPB (101). However, the assemblies of the two structures appear to be independent: septin localization is retained in leading-edge complex mutants, and the leading-edge complex is unaffected in a gip1 mutant where septin localization is lost (163).

The organization of Ssp1p, Don1p, and Ady3p within the leading-edge complex is not known, but localization dependence studies suggest a stratified arrangement (101, 112). Deletion of DON1 does not affect the localization of the other two proteins. Deletion of ADY3 causes the delocalization of Don1p, but Ssp1p remains in a ring at the prospore membrane lip. Deletion of SSP1 causes the disappearance of all three proteins. Therefore, Ssp1p may be the most membrane-proximal component, serving to connect Ady3p to the leading edge, and Ady3p in turn anchors Don1p.

Mirroring this stratified arrangement, the sporulation phenotypes of the three mutants are progressively severe. Mutation of DON1 produces no obvious sporulation defect (76). As suggested by its name, loss of ADY3 (_A_ccumulates _DY_ads) leads to an increase in asci with fewer than four spores (133). The spores present in these dyads are haploid and are packaged randomly with respect to centromere-linked markers, unlike the nonsister dyads described above (101, 112). In fact, in addition to dyads, the culture contains significant numbers of asci with no spores, as well as monads and triads. Surprisingly, the defect in spore formation is caused by a failure of individual spores in the ady3 mutant to form mature spore walls. Cells lacking ADY3 show no apparent defects in prospore membrane formation or nuclear capture by the prospore membrane, but a significant fraction of these prospores fail to elaborate a spore wall (112).

Mutation of SSP1 causes the most severe phenotype: a complete block to sporulation. In these cells, prospore membranes are still formed, but they are grossly abnormal (101). The membranes are tubular rather than round and appear to be adherent to the nuclear envelope. The membranes also occasionally grow in the wrong direction, resulting in a failure to capture nuclei. As in wild-type cells, four membranes are formed; however, in ssp1 cells these membranes often fragment. The ssp1 phenotype demonstrates the necessity for the leading-edge complex (or at least Ssp1p) for proper membrane growth.

While the phenotype of ssp1 mutants is dramatic, it is unclear how loss of SSP1 results in these abnormalities. One proposed explanation is that in the absence of the leading-edge complex, secretory vesicles may fuse only with the outer membrane of the prospore membrane, creating a disproportionate force that pushes the prospore membrane onto the nuclear envelope (101). An alternative possibility is that the leading-edge complex performs functions analogous to the septin ring in budding cells. For example, it could function as a diffusion barrier that distinguishes the inner prospore membrane, which will ultimately become the plasma membrane of the spore, from the outer prospore membrane, which will ultimately be degraded (see below). Although no protein whose localization is asymmetric between these two regions of the prospore membrane has been described, it is tempting to speculate that such proteins exist and that the loss of this asymmetry in ssp1 mutants might lead to some of the membrane defects seen in the mutant.

The position of the leading-edge complex at the mouth of the prospore membrane also raises the possibility that it could play a role in the segregation of organelles into the spore or even in the closure of the membrane. A failure in one of these processes could account for the subsequent spore wall defects seen in ady3 mutants (112). With respect to closure, the leading-edge complex might function in a fashion similar to that of the septins at the bud neck in defining the site of closure. Alternatively, the leading-edge complex might take a more active role in causing the membrane to constrict and close. Whether the leading-edge complex is dynamic or static is an important area for future study.

Membrane closure.

The closure of the prospore membrane is a cytokinetic event, the molecular mechanism of which is unknown. After closure, the cytoplasms of the prospores are distinct from each other and from the mother cell (now ascal) cytoplasm. In electron micrographs of wild-type cells, deposition of spore wall material (identifiable as an expansion of the prospore membrane lumen) is seen only in cells in which the prospore membrane is closed, suggesting that closure necessarily precedes the onset of spore wall formation. This inference is supported by analysis of the gip1 mutant (163). In these cells, prospore membrane formation proceeds normally up to and perhaps including closure, but subsequent spore wall deposition does not occur. This suggests that gip1 mutants are defective either in the process of closure or in a signaling pathway which monitors closure and triggers subsequent events. Although roles for GIP1 (and possibly septins) and the leading-edge complex in membrane closure have been postulated, this remains a largely unexplored area. Several recent studies have described a role for vesicle fusion in the terminal stages of cytokinesis following mitosis in both yeast and animal cells (20, 65, 153, 179). Understanding prospore membrane closure may, therefore, provide more general insights into cell division.

Spore Wall Assembly

The closure of the prospore membrane completes the act of cell division. However, proper differentiation into stress-resistant ascospores requires assembly of the spore wall. As with prospore membrane formation, this is a de novo assembly process. That is, spore wall assembly begins in the lumen between the two membranes derived from the prospore membrane, where there is no preexisting wall structure to serve as a template. Thus, this process is an excellent one with which to explore the assembly of a complex extracellular structure.

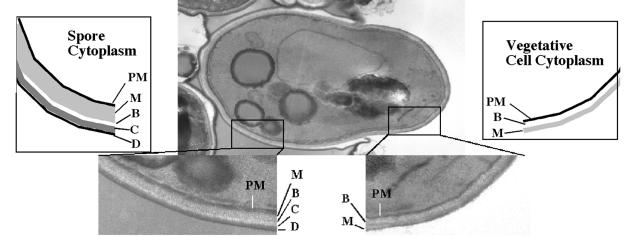

Description of the spore wall.

The spore wall is a more extensive structure than the vegetative cell wall. For comparison, Fig. 7 shows an electron micrograph of a germinating spore, allowing both the spore wall and vegetative cell wall to be seen on one cell. The vegetative wall consists of two major layers, an inner layer (closer to the plasma membrane) consisting primarily of beta-glucan (chains of beta-1,3-linked glucose) with some chitin (beta-1,4-linked _N_-acetylglucosamine) and an outer “mannan” layer consisting of proteins that have been heavily N and O glycosylated with primarily mannose side chains (74). By contrast, the spore wall consists of four layers (156). The inner two layers consist predominantly of mannan and beta-1,3-glucans, although their order is reversed with respect to the plasma membrane; the mannan is interior to the beta-glucan (78). The outer two layers are specific to the spore. Immediately outside of the beta-glucan is a layer of chitosan (beta-1,4-linked glucosamine) (16). Finally, coating the chitosan is a thin layer that consists in large part of dityrosine molecules (18). Unlike the dityrosine found in the extracellular matrices of metazoans (6, 71, 81, 108), the dityrosine in the spore wall is not created by cross-linking between peptides but rather is synthesized directly from the amino acid tyrosine (14, 17). It is these outer spore wall layers that confer upon the spore much of its resistance to environmental stress (13).

FIG. 7.

Comparison of the spore wall and the vegetative cell wall. An electron micrograph of a germinating ascospore is shown. On the left side, the cell is surrounded by spore wall with its four layers, mannan, beta-glucan, chitosan, and dityrosine (indicated by M, B, C, and D, respectively, in the close-up and in the cartoon). On the right side, the tip of the germinating cell is bounded by vegetative cell wall with it predominant beta-glucan and mannan layers (indicated by B and M). The mannan layer of the cell wall appears to be continuous with that of the spore wall. PM, plasma membrane.

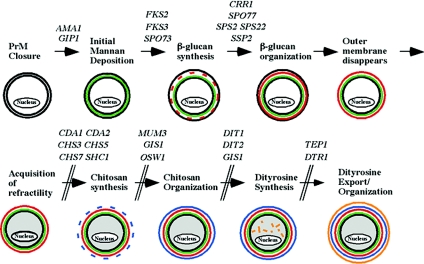

In wild-type cells, formation of the spore wall begins after prospore membrane closure. The layers of the spore wall appear to be laid down in a temporal order, beginning with the innermost mannan layer and moving outward to beta-glucan, then chitosan, and finally dityrosine (163). These observations suggest that feedback mechanisms must exist to coordinate the completion of one layer with the beginning of synthesis of the next layer.

A pathway of spore wall assembly.

Through the analysis of mutants defective in construction of the spore wall, the outlines of the assembly process are beginning to emerge. Two general types of mutations blocking spore wall assembly have been described. Mutation of some genes results in heterotypic spore wall defects, in which different spores within the same ascus display different defects, whereas other mutations cause a more uniform arrest in assembly (27, 45, 79, 172). An analysis of the arrest points in a collection of such mutants led to the definition of the following stages of assembly (Fig. 8) (29).

FIG. 8.

A pathway of spore wall assembly. The steps in assembly of the spore wall are shown. Genes shown to be required for specific steps are indicated (13, 24, 28, 34, 42, 55, 94, 121, 145-147, 163, 168). Adapted from reference 27.

(i) Initiation.

As described above, the GIP1 gene appears to be required for the initiation of spore wall formation in response to membrane closure. Mutation of a second gene, AMA1, displays a block to spore wall synthesis similar to that of gip1. However, ama1 lacks the septin defects seen in gip1 mutants. AMA1 encodes a meiosis-specific regulatory subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (30). Recent studies suggest that Ama1p is regulated so that it activates the anaphase-promoting complex only late in meiosis II (114, 125). These data suggest that AMA1 may be involved in coordinating the onset of spore wall formation with the completion of meiosis II.

(ii) Formation of the mannan and beta-glucan layers.

Following initiation, the first stage of spore wall formation is a deposition of material into the lumen between the two membranes formed from the prospore membrane. This expansion apparently begins with the deposition of mannoproteins, as suggested by the phenotype of a spo73 mutant, which exhibits expansion of the lumen without production of beta-glucans (27).

Assembly of the beta-1,3-glucan layer requires two elements: a beta-glucan synthase that is located in the spore plasma membrane to synthesize and extrude the initial beta-glucan chains into the lumen between the spore plasma membrane and outer membrane (the two membranes derived from the prospore membrane) and wall proteins in this lumenal space to “stitch and weave” these initial chains into the properly assembled wall. There are three genes in S. cerevisiae that encode catalytic subunits of the synthase. FKS1 encodes the primary synthase during vegetative growth (61, 94). GSC2/FKS2 seems to encode the predominant synthase for assembly of the spore wall, although FKS3 may contribute some function as well (34, 94). Several genes that appear to be important for proper assembly of the beta-glucan layer have been identified, including SPO77, SPS2, SPS22, CRR1, and SSP2 (27, 49, 147). It is of note in this regard that some of these genes are sporulation-specific members of sequence families that are involved in cell wall synthesis in vegetative cells. For example, SPS2 and SPS22 are related to ECM33 and PST1, while CRR1 is similar to the glucohydrolase genes CRH1 and CRH2 (27, 49, 122). Additionally, there are sporulation-specific members of the GAS and PIR families of cell wall proteins (25). These sporulation-specific proteins may play roles in the assembly of mannan or beta-glucan layers of the spore wall that are analogous to those played by their counterparts in construction of the vegetative cell wall.

Two other events occur during this stage of spore wall formation that are linked with the completion of beta-glucan layer assembly. First, during this phase the outer membrane derived from the prospore membrane disappears. Second, the spores acquire refractility in the light microscope. Mutants that are blocked in the early stages of spore wall synthesis appear by light microscopy not to form spores, whereas those affected in later steps do make visible spores. However, these spores are not as resistant to environmental challenge as wild-type spores.

(iii) Formation of the chitosan layer.

Once the beta-glucan layer is completed, the spore initiates synthesis of the chitosan layer. The chitosan polymer itself is assembled similarly to beta-1,3-glucan in that a spore plasma membrane-associated synthase, in this case Chs3p, binds nucleotide sugars in the cytosol, couples them, and extrudes the polymer through the spore plasma membrane (53). In vegetative cells, Chs3p is the chitin synthase responsible for the chitin ring around the bud scar. During sporulation, Chs3p again synthesizes chitin (beta-1,4-_N_-acetylglucosamine), but two sporulation-specific chitin deacetylases are present in the spore wall, Cda1p and Cda2p, which deacetylate the chitin, converting it to chitosan (i.e., beta-1,4-glucosamine) (23, 97, 121). The conversion of chitin to chitosan is essential for organization of the outer spore wall layers (24).

In vegetative cells, the activity of Chs3p is controlled both by allosteric regulation of Chs3p and by regulated delivery of Chs3p to the surface (32, 145, 167, 168, 186). Several of the proteins involved in regulated delivery are also important for formation of the chitosan layer during sporulation (34, 168). However, at least one of the allosteric regulators, Chs4p, is replaced during sporulation by a related protein, Shc1p, and other sporulation-specific functions may regulate Chs3p localization during sporulation (see below) (64, 146).

As with beta-glucan synthesis, once the polymer is synthesized by Chs3p it must be properly assembled into the wall. At least two genes, MUM3 and OSW1, that have mutant phenotypes consistent with a role in chitosan layer assembly have been identified (27). While the molecular function of these genes is not known, MUM3 encodes a protein with homology to acyl transferases, consistent with a possible catalytic role in wall assembly (109).

During assembly of the chitosan layer, interspore bridges are formed (29). Chitosan not only surrounds each spore but also branches, creating bridges that connect adjacent spores of a tetrad. These bridges serve to physically connect spores of a tetrad together even when the overlying ascus is removed.

(iv) Formation of the dityrosine layer.

Unlike the underlying layers, the dityrosine layer is composed primarily neither of polysaccharide nor of protein. Approximately 50% of the mass of this layer is composed of nonpeptide N,_N_-bisformyldityrosine (15). The remaining constituents are not well characterized, nor is it known how the dityrosine monomers are coupled to the wall.

The dityrosine molecules are synthesized in the cytoplasm of the spore by the action of the DIT1 and DIT2 gene products (14). These two mid-late genes are divergently transcribed from a common promoter and appear to be induced only after closure of the prospore membrane, as shown by their absence of expression in a gip1 mutant and by the spore-autonomous phenotype of heterozygous dit1 or dit2 mutants (13, 163). The two enzymes act sequentially. Dit1p acts as a formyltransferase that modifies the amino group on l-tyrosine, and Dit2p is a member of the cytochrome P450 family that couples the benzyl rings of two _N_-formyl-tyrosine molecules (14). Both enzymes are cytoplasmic, so the newly formed dityrosine must be exported to the spore wall for assembly. This is achieved through the action of a sporulation-specific ATP-dependent transporter, Dtr1p, localized in the prospore membrane (42). The expression of these three genes, DIT1, DIT2, and DTR1, in vegetative cells is sufficient to allow the production and export of dityrosine (42). The dityrosine is not incorporated into the cell wall under these conditions, presumably due to the absence of the appropriate enzymes and/or substrates to allow its incorporation.

As with the interior layers, assembly of the dityrosine must involve extracellular enzymes that assemble it into a polymerized structure. The identities and activities of these enzymes remain to be determined. Other mutants, such as gis1 and tep1 mutants, that have defects specifically in the dityrosine layer of the spore wall have been identified (27, 55). However, these gene products are nuclear and cytoplasmic, respectively, and so their effects on coupling of dityrosine into the spore wall must be indirect. Homologues of the DIT1, DIT2, and DTR1 genes are found in a variety of other fungi, including pathogens such as Candida albicans and Coccidioides immitis. In C. albicans, dityrosine has been identified in the cell wall (154). Given the importance of dityrosine in conferring stress resistance to S.cerevisiae spores, it will be of interest to learn if these genes play a role in allowing pathogenic fungi to survive in the host.

Regulating spore wall assembly.

The events of assembly described above are inferred largely from the phenotypes of mutants that are blocked at specific points in the process. As noted, several mutations that produce heterogeneous defects in the spore wall have been described (27, 45, 79, 161, 172, 177). These include the protein kinases Cak1p, Mps1p, Smk1p, and Sps1p as well as an integral membrane protein, Spo75p. The heterogeneous phenotypes of these mutants raise the possibility that these gene products are involved in the coordination of the different stages of assembly. Certainly, the fact that many of these genes encode protein kinases would be consistent with roles for these gene products in signaling pathways.

The two best-characterized of these are Sps1p, which is a member of the Ste20/Pak family of kinases, and Smk1p, a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (45, 79). Most characterized MAP kinases are regulated by a cascade involving upstream kinases from the MEK and MEKK kinase families. In the yeast mating response, the Sps1-related kinase Ste20p triggers a cascade that ultimately leads to the activation of the Smk1-related kinase Fus3p (54, 84). Therefore, it was originally suggested that Sps1p and Smk1p might be part of a similar cascade (45, 79). In the interim, however, it has become clear that no sporulation-specific MEK or MEKK homologues are present in S. cerevisiae to link Sps1p and Smk1p. Moreover, SPS1 is not required for the activation of Smk1p (148). Thus, Sps1p does not seem to trigger a MAP kinase cascade.

A recent report indicates that Sps1p plays a role in the trafficking of both the Gsc2p beta-glucan synthase and the Chs3p chitin synthase to the spore plasma membrane. In wild-type spores, both proteins are found uniformly around the spore periphery, but in sps1 mutants these proteins accumulate in a punctate pattern within the spore (64). During sporulation, the activity of these two synthases may be regulated, at least in part, by localization, and Sps1p may be involved in coordinating the delivery of these enzymes to the spore surface. Importantly, smk1 mutants had no effect on delivery of Chs3p, providing further evidence that Sps1p and Smk1p have distinct functions (64).