Will Older Persons and Their Clinicians Use a Shared Decision-making Instrument? (original) (raw)

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine experiences of older persons and their clinicians with shared decision making (SDM) and their willingness to use an SDM instrument.

DESIGN

Qualitative focus group study.

PARTICIPANTS

Four focus groups of 41 older persons and 2 focus groups of 11 clinicians, purposively sampled to encompass a range of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

APPROACH AND MAIN RESULTS

Audiotaped responses were transcribed, coded independently, and analyzed by 3 reviewers using the constant comparative method. Patient participants described using informal facilitators of shared decision making and supported use of an SDM instrument to keep “the doctor and patient on the same page.” They envisioned the instrument as “part of the medical record” that could be “referenced at home.” Clinician participants described the instrument as a “motivational and educational tool” that could “customize care for individual patients.” Some clinician and patient participants expressed reluctance given time constraints and unfamiliarity with the process of setting participatory clinical goals.

CONCLUSIONS

Participants indicated that they would use a shared decision-making instrument in their clinical encounters and attributed multiple functions to the instrument, especially as a tool to facilitate agreement with treatment goals and plans.

Keywords: shared decision making, aged, goal setting

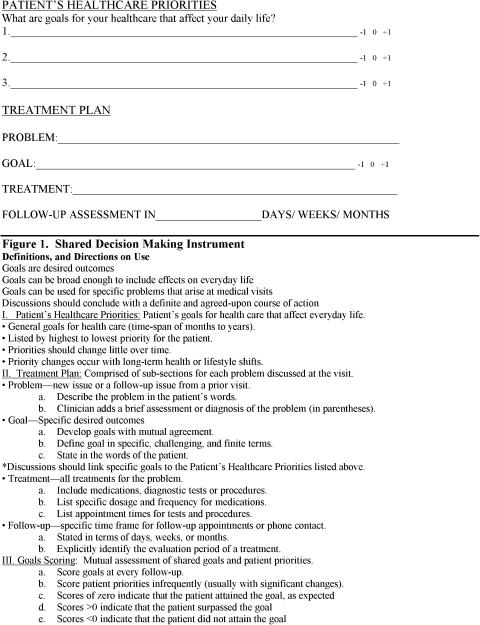

Older persons bring complex and highly individualized medical, functional, and social problems to their clinical encounters, and often have perceptions and preferences for care that diverge or conflict with their clinicians' preferences.1–4 Shared decision-making (SDM) models are increasingly advocated to improve the process5–8 and outcomes1,9–11 of clinical decision making for patients with serious and chronic illnesses; however, few studies4,6,12 have described processes for developing shared treatment plans that older adults might find acceptable.3,13,14 As a first step in developing shared decision-making interventions for the process of geriatric care, we conducted a focus group study of older persons and their clinicians to evaluate the desire for SDM, existing strategies to facilitate participation in decision making, and reactions to a formal SDM instrument. The proposed SDM instrument (Fig. 1) was developed from the principles of goal setting described in the social science literature,15,16 prior work of the authors,2,12 and external review by an expert panel.

FIGURE 1.

Shared decision-making instrument.

METHODS

We used a qualitative study design consisting of 4 focus groups with older adults and 2 with clinicians. We chose focus group methodology to elicit breadth of responses and to encourage intragroup dialogue and exchange of experiences.17 As is common in qualitative studies,18 participants were purposively sampled to ensure diversity in gender, socioeconomic variables, and clinical and functional status. Older adult participants were recruited from 2 urban, subsidized assisted living facilities, 1 suburban assisted living facility, and 1 affluent senior residential community. Participants had at least 1 chronic illness or functional impairment. Clinician focus groups consisted of physicians and nurses in an academic medical center who expressed interest and experience in collaborative health care. Focus groups, which lasted 45 to 60 minutes, consisted of open-ended questions regarding how participants set goals and made treatment decisions in clinical encounters. Participants were also shown the SDM instrument (Fig. 1) and asked “How might this instrument help or hinder your discussions with your clinicians (patients)?” and “What changes would you make?” We used standardized probes to encourage elaboration and discussion of participants' initial responses.18 In all cases, participants were encouraged to give examples and detailed stories that illustrated their statements. The Human Investigation Committee of Yale School of Medicine approved the study protocol.

We analyzed focus group transcripts using the constant comparative method of qualitative data analysis18 to describe common themes from the groups. Three investigators (ADN, DSG, and STB) independently reviewed each transcript line by line, coding quotations with similar concepts into distinct content areas. Using established procedures in qualitative analysis,19 a code key was drafted from a review of the first two transcripts. During coding, new data were constantly compared with previous quotes in the same content areas. When all focus groups were completed, the final code key was reapplied to each transcript. After additional rounds of independent coding, discrepancies among investigators were resolved by careful review, negotiation, and consensus building. Atlas.ti software (version 4.1, Scientific Software Inc., Berlin, Germany) was used for data coding and analysis.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The 6 focus groups consisted of 52 total participants. The 4 groups of older persons had 41 total participants. Patient participants were 82±7 years of age and cognitively intact. Two thirds were female and lived alone. They had, on average, 2 chronic illnesses, difficulty with 2 instrumental activities of daily living, and high self-rated health. There were 2 groups of clinicians consisting of 5 nurses and 6 physicians. They cared for patient panels with primarily older persons. Physician participants were fellows and junior faculty trained in geriatrics and general internal medicine. Nurse participants worked in a geriatrics clinic or rehabilitation ward and had, on average, more than 20 years of clinical experience.

Desire for Shared Decision Making

Focus groups with older persons revealed strong desires to exchange information and preferences for care with clinicians. One woman described the relationship with her doctor as “very strong” because “communication always occurred in two directions.” An older man reported that he would not use medication until he could “talk to the doctor and discuss why you are taking the new medicine and what the medicine is supposed to do for you … and any side effects.” Mirroring the comments of older participants, clinician participants reported implicitly factoring patients' preferences.

Existing Strategies to Facilitate Shared Decision Making

Participants described using an array of informal strategies to improve decision making during clinical encounters. They reported using notepads and tape recorders to increase the quantity and quality of information retained from their encounters. A second method was to bring a detailed list or bag of medications to review with clinicians at each visit to generate discussion of treatment preferences. Several participants described using prioritized lists of complaints and problems to facilitate discussions based on their priorities and preferences. Finally, participants reported bringing second listeners, such as a spouse or family member to the visit to improve the exchange of information and preferences and to help interpret information given by clinicians.

Acceptance and Functions of a Shared Decision-making Instrument

Patients' Perceptions

Overall, participants reported positive perceptions of the SDM instrument. Few participants expressed unwillingness to accept the instrument in their clinical encounters. Patient participants described potential functions of the SDM instrument (Table 1). An older woman described the instrument's utility as a reference tool,

Table 1.

Potential Functions of a Shared Decision-making Instrument

| Function | Comments |

|---|---|

| Reference tool | “Take home and use as a reminder” |

| Organizes discussion | “Helps patients address all their concerns” |

| Develop concordance | “Keeps doctors and patients on same page” |

| Customizes care | “It's good for the complex or problem patients … so you can work out the barriers” |

| Improves education | “It's a vehicle for tailored education” |

| Motivational tool | “They can actually see what they have really done, it's a big encouragement [for patients]” |

I think it would be useful for me to have a copy of this form at home … to have written information to look at after you get home that supplements your memory.

Another man expressed his perceptions of the instrument as a means to improve agreement,

I think it would be good to have so [the doctor] would know what you are thinking and you would know what he was thinking and it would help you … so we'd [the doctor and patient] be on the same page.

Negative perceptions reported by older persons centered on the reluctance of clinicians to use the form, given time constraints. In addition, one participant expressed his negative view of the whole concept of SDM as follows,

I don't know why we need this. I mean we've been going along for 80 years without any and you go to the doctor and you are depending on his knowledge. He tells you what to do, you walk out and you go get a prescription filled.

Clinicians' Perceptions

Clinician participants expressed generally positive perceptions of the SDM instrument and identified several additional functions (Table 1). One geriatrician asserted,

I really think [the instrument] is good for the complex patients or your problem patients where you're just not getting anywhere with them.

Nurse participants described the educational and motivational roles of the instrument. However, clinicians did express some reservations about using a formal SDM instrument. One physician said,

I think if you gave [the instrument] to some patients they would be confused. I don't think they understand medical care [in terms of] patient goals and preferences.

Another physician described economies of time that the instrument could accomplish:

Do we have time in a 15-minute encounter to write it out as a physician? I don't know …. Some might also argue that if you would take some time to do this on your own, the overall quality of care would be more effective and more efficient …. To save time so the next ten visits you are not addressing the same basic issues.

DISCUSSION

The findings of the current study enrich the shared decision-making model1,7,8 and counter the notion that older persons shun participatory medical decision making.3,13,14 While no universal definition exists, models of SDM typically describe 3 key elements: information exchange, deliberation regarding preferences, and developing agreement between clinician and patient (i.e., concordance) with treatment goals.2,7,8 Older persons in the current study described their desire to exchange information and express preferences for care. These desires were aligned with participants' practice of using various informal strategies to facilitate 2 of the 3 elements of SDM. At the same time, they identified few instances of treatment plans based on collaborative goals and offered no examples of using informal facilitators of concordance. Some participants did propose, however, that the SDM instrument could facilitate discussion and collaboration regarding treatment goals and plans.

The results of this qualitative study are not universally generalizable as we sampled only a small group of older persons, nurses, and physicians. Clinicians from other specialties or practice locations may offer different insights regarding SDM. Our recruitment procedures did attempt to capture a diverse group of older participants; therefore, the comments and perceptions offered by the study participants may resonate, generally speaking, with other older persons. In addition, the study was not designed to validate an SDM instrument, and participants offered important caveats. Qualitative methodologies are ideally suited to generate, rather than test, hypotheses. As such, this study suggests that SDM for older patients is feasible, but may require more than physician-directed decision aides.20 Additional empirical research in this area will be necessary to confirm this hypothesis. Instruments that enable the process of SDM could engender a paradigm shift in medical decision making from the current practice of identifying and applying objective and utilitarian treatments for disease, to one of customizing treatment based on a patient's life and health goals.11,12,20

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Harlan Krumholz, MD for reviewing an earlier draft of this manuscript, and Shirley Hannon, RN for her assistance with participant recruitment and data collection for this study. This research was supported by a center grant from a joint program of the Hartford and RAND foundations: Building Interdisciplinary Geriatric Health Care Research.

References

- 1.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogardus ST, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Maciejewski PK, van Doorn C, Inouye SK. Goals for the care of frail older adults. do caregivers and clinicians agree? Am J Med. 2001;110:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strull WM, Lo B, Charles G. Do patients want to participate in medical decision making? JAMA. 1984;252:2990–2994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, Carver D, et al. A clinimetric evaluation of specialized geriatric care for rural dwelling, frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1080–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quill TE. Partnerships in patient care. a contractual approach Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:228–234. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-2-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter. revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulter A. Partnerships with patients. the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making J Health Serv Res Policy. 1997;2:112–121. doi: 10.1177/135581969700200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogardus ST, Jr, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Maciejewski PK, Gallo WT, Inouye SK. Achieving goals in geriatric assessment: role of caregiver agreement and adherence to recommendations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasgow RE, Anderson RM. In diabetes care, moving from compliance to adherence is not enough. Something entirely different is needed. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:2090–2092. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley EH, Bogardus ST, Jr, Tinetti ME, Inouye SK. Goal-setting in clinical medicine. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:267–278. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1414–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beisecker AE, Beisecker TD. Patient information-seeking behaviors when communicating with doctors. Med Care. 1990;28:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin J, Vancouver J. Goal constructs in psychology. structure, process, and content Psychol Bull. 1996;120:338–375. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locke EA, Latham GP. The Theory of Goal-setting and Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huberman M, Miles MB. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Korff M, Glasgow RE, Sharpe M. Organising care for chronic illness. BMJ. 2002;325:92–94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]